Abstract

European identity among youth remains under-studied despite having the potential to promote inclusive benefits. Through a rapid evidence assessment (REA), this paper addresses two aims. First, it synthesises definitions of European identity among children, adolescents and young adults through thematic analysis, and summarises measurements. Second, it summarises the constructs associated with European identity among youth, providing a broad overview of existing research. Based on thematic analysis, European identity is operationally defined as a complex identity with which youth may choose to identify, uniting people based on a diverse range of factors but acknowledging the diversity of national roots and, in turn, affording benefits due to the sense of belonging it provides. School-based interventions and curricula, knowledge about Europe and the EU, political trust, benefits of the EU, and cross-border experiences, along with enhanced intergroup attitudes and civic engagement, are associated with stronger European identification. Avenues for future research are identified, including the need for a developmentally appropriate measure of European identity, the investigation of its relationship with other constructs, and exploring the potential of curricular interventions to promote the inclusive aspects of European identity on a national scale, particularly among younger pupils.

1. Introduction

In an increasingly globalised world, a host of higher-order, or superordinate, identities are becoming more and more relevant. These broad group memberships have the potential to promote inclusive benefits as they can encompass a diverse range of individuals and groups [1]. This is particularly relevant among youth, a cohort upon whom intervention to promote more inclusivity can be particularly effective, as any biases that they hold are not yet deeply rooted in their thinking [2]. However, the intricacies of superordinate identities, such as European identity, are yet to be fully understood. The first step in developing a cohesive understanding of any phenomenon and identifying avenues for further research is to synthesise what is known. Using a rapid evidence assessment (REA) [3,4], this paper summarises how European identity among youth is defined and measured, along with the constructs associated with it. This approach provides novel insights into research on European identity in children and young people and highlights avenues for future research.

European identity is studied across several disciplines, and how it is defined varies [5]. Across areas such as social psychology, politics and sociology, authors typically consider European identity in relation to national identity [6] and refer to emotional and cognitive dimensions [7,8], political and cultural aspects [9], and belonging to a superordinate group [8,10,11]. Broadly, European identity pertains to a sense of attachment to Europe and the European community, involving social, political, and psychological factors [5,6,12]. However, precisely how European identity is conceptualised varies, prompting claims of a vague [12] and ill-defined [13] construct. A study that synthesises what researchers consider to be the core components of European identity, particularly in youth, is crucial to creating a more comprehensive understanding of European identity.

European identity in youth may yield individual and social benefits. The Common Ingroup Identity Model asserts that intergroup bias can be reduced by prompting individuals to recategorise themselves and others into one unifying group (e.g., Europeans) [1]. Supporting this idea, stronger European identities are associated with more positive attitudes towards immigrants among young adults [14], prosocial (i.e., helping) behaviours towards conflict rivals among 7–11 year-olds in post-accord societies [15], and solidarity with other European member states among adults [16]. Moreover, social identity is a key source of young people’s sense of belonging [17]. Belonging, in turn, is crucial to their wellbeing [18] and educational achievement [19]; identifying with a particularly broad group (e.g., Europeans) could feasibly bolster these positive outcomes. Finally, because European identity is primarily a civic identity [20], it is likely to be associated with civic behaviours, which are key to sustaining democracy [21]. Thus, European identity has the potential to promote individual and social benefits; however, we also consider whether there are risks associated with identification at this superordinate level.

The construction of any social identity necessarily entails the construction of an outgroup, which, under certain circumstances, may be the subject of derogation and discrimination [17]. This possibility is reflected in long-standing concerns about a Europe which benefits those within its boundaries but within which negative attitudes and exclusionary policies are targeted towards those outside these borders [20]. Moreover, the ever-shifting nature of EU borders means that it is sometimes unclear who is or is not European (e.g., individuals from countries that have left the EU, such as the UK, or which are engaged in the EU accession process, such as Ukraine, Turkey or the Western Balkans) [20]. Individuals in these contexts may or may not feel European, and may or may not be perceived as European by others, which can have consequences for intergroup attitudes and relations. When considering the inclusive and civic potential of European identity, it is also important to consider these potential pitfalls.

When considering how to harness the benefits associated with European identity, a focus on youth is particularly advantageous, as European identity and intergroup biases are under development in this cohort. European identity develops between ages 7 and 11 [22] and crystallises in adolescence (ages 12–18) and young adulthood (ages 18–25) [7,23]. Moreover, outgroup prejudice typically begins to emerge at around age 7, with intergroup attitudes and biases evolving across middle childhood (i.e., ages 7–12) [17] and adolescence [24]. As identities, intergroup biases and political identities are in a state of development during childhood, adolescence and young adulthood, these factors have not yet become deeply entrenched in young people’s thinking and are thus more susceptible to change [2,24]; such change is more difficult to achieve among adults [24]. Thus, understanding European identity and its correlates during these key developmental periods can inform interventions that may have a greater impact than interventions among adults. Despite this empirical relevance, youth are an under-studied cohort in the European identity literature [15,25,26]. Summarising what is currently known about European identity among youth is crucial to the identification of avenues for further research and the development of interventions.

To our knowledge, only one paper has synthesised qualitative studies on this topic, specifically on university students’ perceptions of European identity [27]. This qualitative evidence synthesis found that proficiency in foreign languages, transnational travel experiences, and educational interventions were associated with stronger European identification among university students [27]. The current study builds upon these findings in two ways to investigate how European identity is described and measured among youth. First, it expands the scope to include both qualitative and quantitative studies. Second, it extends the ages to include children, adolescents, and young adults.

Rapid evidence assessments (REAs) use a systematic process to provide an overview of evidence on a discrete topic [4]. The present study employs an REA to address two aims. First, to address the lack of consensus around the definition of European identity [12,25], existing measurements and definitions are synthesised through thematic analysis [28]. Second, to gain a better understanding of European identity among youth, the constructs associated with it are identified and discussed.

2. Materials and Methods

This REA was preregistered on OSF at https://osf.io/ycnrg (accessed on 1 July 2024).

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Based on the aims of this REA, inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed, which guided each stage of the review process. Studies were excluded if they did not meet the below criteria:

- Participants were aged between 4 and 25 years, encompassing the period from just before the beginning of middle childhood, to the end of young adulthood. Thus, studies covering a range of key developmental stages could be included [22,29]. An inclusive approach was employed; if the majority of participants were aged between 4 and 25 [30,31], or if one of the groups of participants fell within the target age range [32], studies were included.

- Studies measured individuals’ European identities, sense of European “belongingness”, identification with Europe, or attachment to Europe; for example, studies measuring national identity in a European context but not European identity were excluded.

- Studies involved empirical research.

- Studies involved the self-report of 4–25-year-olds or adults (e.g., parents, teachers) reporting on 4–25-year-olds in their care.

- Studies were written in English.

2.2. Search Strategy

To synthesise the systematic review process, a common REA strategy of imposing restrictions on literature searches [3] was adopted.

First, search results were filtered to include the top ten journals (based on their SCImago Journal Rankings) [33] in relevant disciplines (i.e., psychology, politics, sociology, education, and economics) [34]. If one of the ten highest-ranked journals in the 2021 SJR did not feature articles relevant to the search (e.g., “American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics”), the next highest journal in the list was included (Appendix A).

Second, search results were filtered to include articles published in a list of European journals. This list was generated by searching Web of Science’s journal coverage list for “European journal of” and applying a range of filters (Appendix B). In total, 183 journal titles were generated, of which a subset of 66 were considered potentially relevant (e.g., the “European Actuarial Journal” was excluded as not relevant; Appendix C). To cross-check relevance within a discipline, a second independent search was conducted using the same filter (“European Journal of”) in PsycINFO. The two lists of potentially relevant journals were compared. The PsycINFO search yielded a list of 45 journals, of which 11 were judged by the researchers to be potentially relevant. Each of the 11 journals identified in the cross-check also appeared in the list of Web of Science journals; therefore, the Web of Science list was considered sufficient, and the 66 journals within it were included in subsequent screening phases.

A systematic search for papers published in relevant journals was conducted on the Web of Science platform. Titles and abstracts of articles were searched for terms related to the target age range of participants (Child* OR adoles* OR youth* OR teen* OR juvenile OR young adult* OR emerging adult* OR minor OR kid) and European identity (European Identity OR European Identification).

2.3. Screening and Data Extraction

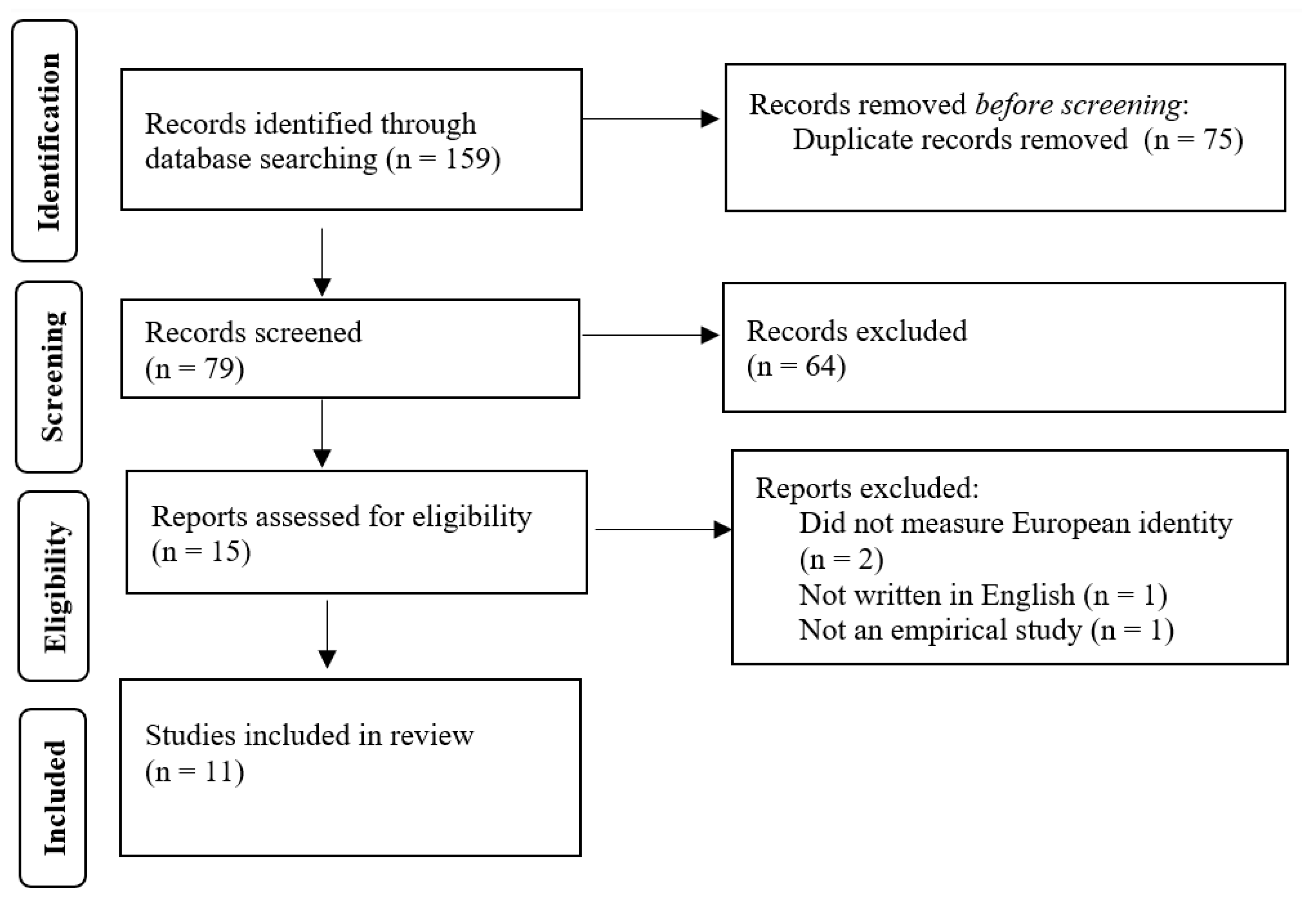

The search yielded 79 references, which were exported to Covidence systematic review software (www.covidence.org (accessed on 1 July 2024)). Each stage of the screening and data extraction process is represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Prisma Flow Diagram for REA.

Two independent reviewers completed the title and abstract screening. Reviewer 1 (first author) screened 100% of the papers, while Reviewer 2 (second author) screened 20%. This resulted in a Cohen’s Kappa of 0.89, indicating strong inter-rater reliability [35]. Disagreements arose from varying levels of certainty regarding the age of participants and were discussed before being resolved by Reviewer 1. At this stage, 64 papers were excluded, as they did not meet the inclusion criteria outlined above.

Fifteen studies were subject to full-text screening; both reviewers screened 100% of the studies. Cohen’s Kappa was 0.67, indicating moderate inter-rater reliability [35]. Disagreements were discussed and resolved. Four studies were excluded, as they did not measure European identity, were not written in English, or were not empirical studies.

The final 11 papers were extracted by Reviewer 1, following an extraction template that included (1) study characteristics, (2) participants, (3) methods, and (4) results (Appendix D).

2.4. Quality Appraisal

The Joanna Briggs Institute Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies [36] and Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist for systematic reviews [37] were consulted to identify three potential threats to study quality: ethical issues, selection bias, and lack of methodological rigour (Appendix E). All papers were rated based on their risk of bias in these domains, and deemed to be of sufficient quality to be included in the analysis, though Reviewer 1 marked ethical concerns as “unsure” for 9 studies, largely due to a lack of reporting on how ethics was considered or ethical approval obtained.

2.5. Evidence Synthesis

The 11 included papers were analysed using thematic analysis [28], guided by the first aim of this REA: to summarise how European identity is conceptualised and defined by researchers. The analytic approach selected followed Braun and Clarke’s six-step approach to thematic analysis [28,38,39]. Analysis was guided by a critical realist epistemology, assuming that there is an objective reality, but one which is understood and interpreted differently by those who inhabit it [28,40]. Thus, in the present thematic analysis, researchers’ understandings of European identity were understood to be constructed by them, but within the constraints of existing scientific theory and political and social structures (e.g., the EU). Thematic analysis, as a theoretically flexible analytic method, was an appropriate analysis technique to use within a critical realist framework [28]. A blend of inductive and deductive coding techniques was used, with mainly semantic (i.e., surface-level) inferences made and assuming a relatively straightforward relationship between language and meaning [28].

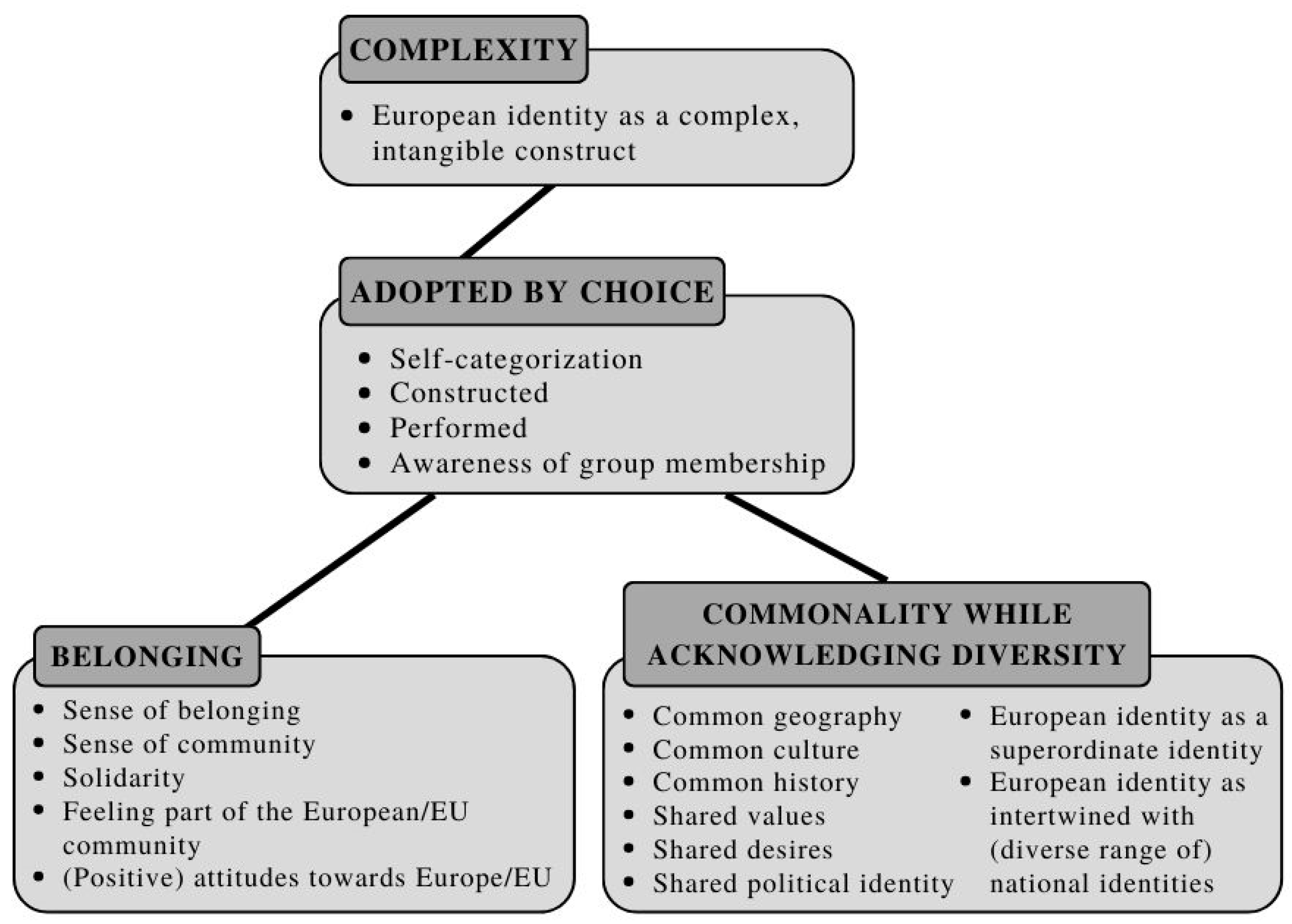

Papers were read several times for familiarisation, and preliminary codes were noted. A dynamic process of re-naming and refining codes into meaningful groups was instigated, and preliminary themes were constructed. As early thematic maps were designed and refined, some codes became themes, some themes collapsed into each other, and the relationship between codes and themes was considered. When a final thematic map (Figure 2) was generated, themes were defined and named.

Figure 2.

Thematic Map of Definitions of European Identity. Note. Theme names are depicted in dark grey; codes are depicted in light grey.

The preregistration stated that the second and third aims of the study were to synthesise (a) the predictors and (b) the outcomes of European identity. However, the majority of the studies included in the review were cross-sectional or qualitative; thus, causality could not be inferred from their findings. These aims were therefore collapsed into one, more appropriate aim: to synthesise some of the constructs which are associated with European identity.

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

The REA identified 11 empirical studies investigating European identity and the constructs associated with it in children and young people, reporting on data from 24 of the 27 EU member states (all member states except Croatia, France and Romania) and the United Kingdom. Articles were published in journals in psychology (n = 4), politics (n = 2), sociology (n = 3) and education (n = 2). The study characteristics are depicted in Table 1; noteworthy are the observations that several studies did not report on some or multiple characteristics (e.g., participant recruitment), that most studies had more female than male participants, and that only one study focused on participants below 12 years of age.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included in the REA.

3.2. Defining and Measuring European Identity

During the thematic analysis of definitions of European identity, a set of four distinct but interlinking themes (complexity, adopted by choice, belonging and commonality while acknowledging diversity) was constructed (Figure 2).

Across papers, the complexity associated with European identity was discussed. Some papers directly alluded to the intricacy and intangibility of European identity [30,44]. In others, it became evident that a consistent scale or tool to measure European identity among youth was not in use (see Appendix F for a list of scales). Despite this variability, when measuring European identity, quantitative studies focused on the strength of participants’ European identification, pride, and “feeling” part of Europe, tapping into the belonging dimension of European identity. Qualitative studies were more diverse, exploring perceptions of and knowledge about Europe [30,32,42,43], European symbols [44], feelings of belonging, and the strength of identity [43]. However, what is clear and widely acknowledged [30] is that none of the methods currently in use are likely to capture all dimensions of European identity among youth. Complexity permeates the remaining themes.

When discussing youth European identity, the authors described a general feeling of belonging, which is fundamental to identification as European [41,44]. The authors conceptualised European identity as a sense of solidarity [32,41,44] with “a European community of citizens” ([43] p. 129). They discussed belonging in terms of youth feeling part of Europe and the EU [41,42,48] and their attitudes and feelings about Europe and the EU [30,32,42,43]. However, there were discrepancies in how these latter domains were considered. While some studies measured belonging to both Europe and the EU to tap into European identity [44,47], Brummer et al. (2022) separated the two, focusing solely on feeling a part of Europe. Similarly, some authors argued that young people’s attitudes towards Europe and the EU are distinct from their European identities, as the former are purely cognitive, while the latter also have an emotional aspect [48], while others frame attitudes as one substantive element of European identity [30,42,43]. These discrepancies reflect the lack of a formal definition of European identity in the existing literature.

European identity is adopted by choice by children and young people; authors referred to youths’ “self-identification as European” ([47], p. 651). Researchers agree that youth are not only aware of their group membership [48], but this membership is also constructed and performed [43], “constantly and collectively created, reconstituted, or combined” ([41], p. 181). Young people then chose to adopt this identity into their self-concept voluntarily (though, as is discussed later, this may only be possible when they feel that Europe is an accessible category to them).

Finally, the authors discussed how young people’s European identity was based on commonality with fellow Europeans, while acknowledging the diversity among them. European identity is a superordinate category encompassing a variety of national groups with differing histories, cultures and languages [46]. However, these groups share commonalities as Europeans. Researchers have discussed European identity as being grounded in a common culture, history, and geography, describing it as a “birth-right” and linked with “place-belongingness”, or emotional ties to a particular location ([44], pp. 441, 443). Several papers alluded to young Europeans’ shared desires, “the feeling that the EU truly represents [people’s] common interests” underpinning European identification ([48], p. 127). European youth also share a political identity, with European identification conceptualised as a manifestation of young people’s “commitment as European citizens” ([31], p. 324) and “the inclusion of the European policy level in [their] social identity” ([48], p. 127).

3.3. Constructs Associated with European Identity

The second aim of this study was to summarise the constructs that were associated with European identity among youth. Across the studies included in this REA, these included minority status, socioeconomic status, age, sex, intergroup attitudes, educational curricula, knowledge about Europe and the EU, political trust, the benefits of EU membership, and civic engagement. A list of the measures used for each variable is included in Appendix G.

3.3.1. Which Young People Identify with Europe?

According to the thematic analysis of definitions, belonging was a core component of European identification, and youth adopted European identities by choice. However, the degree to which young people identified as European varied based on a number of sociodemographic variables. Minority-group status, socioeconomic status and the associated opportunities, age and sex were related to how much youth identified with Europe, though with varying levels of consistency.

The degree to which members of minority groups identified with Europe was considered across four papers, which, in combination, suggest that the degree to which minority youth can identify with Europe depends on local and contextual factors. In one qualitative study, 16–24-year-old members of ethnic minority groups (i.e., Russians, Belarusians and Poles) in Lithuania had varying levels of European identification. Complex considerations regarding the economic implications of EU membership, fears about a loss of cultural diversity in Europe, and perceived cultural commonality with citizens of other European countries tempered their identification (or lack thereof) with Europe [32]. Other qualitative enquiries suggest that Turkish 15-year-olds in England and Germany were more likely to identify with Europe when it was defined by schools as based on multiculturalism and explicitly inclusive of Turkey, rather than based on Whiteness and Christianity; moreover, local levels of interethnic conflict made it difficult for them to identify with their host nation and with Europe [42,43]. In Belgium, Turkish and Moroccan youth aged 16–19 had similar levels of European identification to their Western European counterparts [41]. These studies provide promising evidence that European identity can encompass a range of ethnic, religious and cultural groups from within and outside the EU; however, who this identity feels accessible to may vary based on the national and local context.

Socioeconomic status was another important correlate, with youth from higher socioeconomic backgrounds identifying more strongly with Europe [42,43,45,47]. In these studies, it was suggested that this could be because wealth affords opportunities to travel across Europe, participate in the European community, and learn about other countries within Europe [42,43,45,47]. Indeed, transnational experiences through short- and long-term cross-border travel [31] and friendships with individuals in other European countries [47] were positively associated with European identity for 14–30 year-olds in countries across the EU. Thus, European identity may be a more accessible category for youth in higher socioeconomic groups, who can more easily avail of the benefits of European membership (e.g., cross-border travel).

Findings pertaining to the link between European identity and other demographic variables were less clear. For example, while youth identified more strongly as European than older adults [32], there was variation in whether older [32,46,47] or younger [45] youth had stronger European identities. Similarly, findings for sex varied. While female participants identified more strongly as European than male participants in one study [48], another showed that this was only the case for minority-group girls [41]. Another study still showed no significant effect of sex on identification, although boys had higher levels of trust in and more opinions about, the EU [47]. A final study showed that while more female participants identified solely as European, more male participants had dual national and European identities [46]. Thus, findings regarding age and sex are varied and complex, preventing any meaningful conclusions from being drawn.

3.3.2. The Role of Education

Seven of the eleven studies in our sample recruited participants from schools and universities, so it is unsurprising that several assessed the relationship between school curricula and European identity. Cementing the idea that the degree to which minority youth identify with Europe depends on contextual factors, several studies in the REA considered school curricula in relation to minority youths’ European identification. In a qualitative study, 15-year-old Turkish students in a German school that adopted a broad, “Multicultural European” ethos endorsed hybrid national-European identities. In contrast, minority students in schools with more Eurocentric or nationally framed curricula, which discussed Europeanness in terms of (Western) Europe’s predominantly white, Christian origins, were less likely to adopt Europe as a dimension of their identities [42,43]. For Turkish and Moroccan 16–19-year-olds in Belgium, perceptions of a multicultural dimension in the school curriculum were more strongly associated with European identification than perceptions of a European dimension, although both dimensions were associated. There was no significant difference in the effects of these two dimensions on the identification of students from Western Europe [41]. Thus, the way in which Europe is framed in school curricula appears to have important implications for how included young people feel within it and consequently for their European identification, particularly for minority youth.

For children aged 9–10 in England, participation in an art-based educational programme provided insight into their construction of European identity, which was communicated through symbols such as flags and holiday destinations [44]. Knowledge about and attitudes towards other European countries were also proposed as contributors to European identity [30]. Indeed, adolescents’ knowledge about Europe and the EU was significantly and positively associated with European identity, although their perceptions of EU membership as yielding economic benefits and their trust in national-level political institutions were more strongly associated with European identification [48]. Thus, while school curricula are associated with the development of European identity, they are not the only or the strongest associated constructs when compared to political trust and the perceived benefits of EU membership.

3.3.3. Who do Europeans act Inclusively towards?

Two studies assessed whether European identity was associated with more inclusive attitudes towards a range of outgroups. Based on these studies, European identity appears to be broadly inclusive.

For 13–18-year-olds in Hungary, European identification was positively correlated with affect for ingroup Hungarians and (positive) trait attributions and affect for Romanians and Americans. However, it had no significant effect on affect or trait attributions for Russians [45]. It is plausible that Romanians, as EU citizens, and Americans, as European allies, were considered relevant comparators in the European context, whereas Russians were not [45].

In another study recruiting youth aged 14–30 from countries across Europe, including the Czech Republic, Germany, Greece, Estonia, Italy, Portugal, Sweden and the UK, youth who had stronger European identities exhibited significantly more tolerance toward refugees than those with strong national identities, or strong European and national identities [46]. However, youth who did not identify with either national or European identities reported similar levels of tolerance for refugees to those who strongly identified with Europe [46], suggesting that strengthening European identity is not the only way to bolster inclusive attitudes. Based on this evidence, it appears that young people’s European identity can promote inclusive attitudes and behaviours towards a range of groups from within and outside the EU.

3.3.4. Civic Components

Young people who identified strongly as European were more engaged in social and political life. Youths aged 14–30 who identified strongly as European were significantly more interested in politics than those with strong national identities, and youths with strong European and national identities had even higher levels of political interest [46]. Furthermore, the latter group demonstrated significantly higher levels of political participation than youth with only a strong national identity [46]. Also, in the domain of civic engagement, European identity significantly mediated the relationship between 14–30 year-olds’ cross-border friendships and both participation at an EU level and intentions to vote in the next EU parliamentary elections [31]. Young people’s visions of the EU as a political community and as a community of shared values were also significantly and positively associated with EU participation and voting intentions. Viewing the EU as an economic community was negatively related to EU participation [31]. This points to the role of different framings of Europe and the EU in shaping young people’s political behaviour.

4. Discussion

This REA summarised measures, definitions and constructs associated with European identity among youth. European identity was captured through four themes. European identity is inherently complex, incorporating several dimensions, and is one that young people can adopt by choice. This decision to identify with Europe appears to be based on (perceived) commonality with fellow Europeans through dimensions such as shared culture, history, desires, geography, and political identity while acknowledging diversity in terms of their historical, cultural, and linguistic roots. For those who identify with Europe, this category is intrinsically related to belonging. European identity was associated with higher socioeconomic status, enhanced intergroup attitudes, knowledge about Europe and the EU, political trust, perceived benefits of EU membership, and civic engagement. Educational curricula played an important role in its formation, with narratives about Europe and the EU proving to be important, particularly for minority youth. Age and sex were associated with European identification, though not consistently.

Based on the thematic analysis, European identity among youth can be operationally defined as a complex identity with which youth may choose to identify, uniting people based on factors such as culture, geography, history and politics but acknowledging the diversity of national roots, and in turn affording benefits due to the sense of belonging it provides. The multifaceted nature of this definition means that different elements of European identity are emphasised by different researchers, depending on their field of study, which likely contributes to the broader debate on the nature of European identity [5,13]. However, based on the thematic analysis in this study, we argue that European identity is clearly defined, with studies included in this REA and in the broader literature [7,8,9,12] consistently drawing on similar concepts.

The myriad dimensions of European identity as defined by researchers are reflected in the diversity of understandings among laypeople and in dominant cultural narratives, which can have positive or negative consequences. Framing European identity in a multicultural sense allows youth from minority groups to feel more included in the European category and identify more with it [41,42,43]. Moreover, when participants’ perceptions of Europe stress its political and community-based elements, identification is associated with increased political participation [31]. However, when European identity is defined in a manner emphasising Western Europe and its roots in Christianity, along with its predominantly White population, minority youth are less likely to feel that they fit within the European category or identify with it [42,43]. While not explored by studies in this REA, it is plausible that emphasising the ethnocultural roots of European identity could have similarly detrimental impacts on majority-group attitudes towards ethnic minorities. This could occur through prompting (Western) Europeans to have negative attitudes towards migrants who are from geographically or culturally distant nations [20,49]. Thus, emphasising different dimensions of European identity can yield benefits or promote exclusion. Future studies should further investigate whether it is possible to promote the forms of European identification that are most likely to promote belonging among diverse cohorts of young people and increased political participation.

Limitations and Future Directions

An REA is limited and provides a snapshot of the literature. For example, in this study we excluded papers that were related but did not directly assess young people’s European identities on an individual level [50]. While this facilitated a focused analysis of what is known about young people’s European identities, it also meant that only 11 papers were included in the REA. Moreover, many of the studies reported in this paper were cross-sectional in nature [31,41,45,46], meaning that causality cannot be inferred. It is also noteworthy that the studies included in this REA recruited a range of different samples, measures of European identity, and designs, making direct comparisons of their findings difficult and limiting the conclusions that could be drawn. Further, more broadly reaching scoping reviews could shed further light on the existing research.

Notwithstanding the above limitations, avenues for future research can be derived from this REA. First, there is a need for a developmentally appropriate measure of European identity among youth, which should incorporate the dimensions outlined above. Second, only one study in our sample focused on children below the age of 12; future studies should investigate this age group, particularly considering that European identity develops in middle childhood [22]. Third, certain constructs that may be associated with European identity among youth were notably absent from the included papers. For example, mirroring findings among adult populations [51], personality traits may influence young people’s European identification. Furthermore, given the positive effects of superordinate identification on psychological well-being and educational achievement, particularly among vulnerable minorities [52], European identification may promote similar outcomes among youths. Future studies could also investigate in greater detail how young people’s European identification relates to the perceived impact of the EU on local factors, such as levels of migration and labour market prospects; this could yield further insights into the relationship between, for example, socioeconomic status and European identification among youth. Moreover, they could explore the implications of member states leaving the EU for children’s European identification and its correlates (e.g., the consequences of Brexit [53]). Fourth, future studies should investigate the shifting boundaries of European identification among youth, their implications for intergroup relations, and the conditions under which more inclusive conceptualisations of Europeanness develop.

Building on studies that illustrate the importance of curricular interventions in shaping more inclusive concepts of Europeanness [25,41,42,43], future studies could investigate the role of educational curricula on a broader scale with younger populations. This is particularly important given the accessibility of education compared to transnational experiences for lower socioeconomic groups [42,43]. The Erasmus, Comenius and Leonardo da Vinci programmes are popular and widespread initiatives within this domain, targeting older youth and young adults [25]. However, to our knowledge, similar initiatives have yet to be investigated among children, who are an optimal group for intervention due to the fact that European identity develops across middle childhood [22]. Thus, a promising avenue for future research is the role of national curricular interventions for primary school-aged children in promoting (inclusive) European identities. One such programme is the Blue Star Programme in Ireland, which aims to promote knowledge about Europe and the EU through creative activities [54]. Assessing the influence of such a programme, which is tailored to promoting knowledge about Europe, would yield insights into how children form their European identities and facilitate further testing of whether certain curricula promote more inclusive identities.

5. Conclusions

This paper offers a systematic synthesis of European identity among children and young people, suggesting that European identity can be adopted by choice and has a complex nature that incorporates dimensions of belonging, similarity, and difference. It summarises the constructs associated with European identity among youth and suggests that future research should develop a developmentally appropriate measure of European identity and investigate constructs such as personality, well-being, and educational outcomes. Finally, this REA suggests that due to their accessibility, curricular interventions to enhance (inclusive) European identity should be investigated on a broader scale, particularly among younger pupils. This is important for the inclusion of a growing number of migrants [55,56] and ethnically and culturally diverse groups in Europe [57], with implications for social cohesion across the continent.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.N.C. and L.K.T.; Methodology, I.N.C. and L.K.T.; Validation, I.N.C. and L.K.T.; Formal Analysis, I.N.C.; Investigation, I.N.C.; Resources, I.N.C. and L.K.T.; Data Curation, I.N.C.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, I.N.C.; Writing—Review & Editing, I.N.C. and L.K.T.; Visualization, I.N.C.; Supervision, L.K.T.; Project Administration, L.K.T.; Funding Acquisition, L.K.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

While working on this manuscript, INC was supported by funding from Enterprise Ireland, grant number EC20221231, and University College Dublin Seed Funding, grant number SF2025 to LT.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Further information is also included in the Appendix.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank members of the Helping Kids! Lab, particularly Mary-Jane Emmett and Courtney Rungatis, for their feedback on drafts of this manuscript. Moreover, we would like to thank the incredible staff of the Blue Star Programme (https://www.bluestarprogramme.ie/ (accessed on 1 July 2024)) for collaboration in the conceptualization of this line of research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

This appendix outlines the “Top 10” journals in each relevant discipline.

Table A1.

“Top 10” journals in psychology.

Table A1.

“Top 10” journals in psychology.

| Psychology | Relevant Article? (Y/N) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry | N |

| 2 | Journal of Educational Psychology | N |

| 3 | Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology | N |

| 4 | European Journal of Personality | N |

| 5 | Psychological Medicine | N |

| 6 | Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin | N |

| 7 | Child Development | N |

| 8 | Computers in Human Behaviour | N |

| 9 | Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology | N |

| 10 | British Journal of Social Psychology | N |

Table A2.

“Top 10” journals in Political Science & International Relations.

Table A2.

“Top 10” journals in Political Science & International Relations.

| Political Science & International Relations | Relevant Article? (Y/N) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Political Science Research and Methods | N |

| 2 | European Union Politics | Y |

| 3 | Review of International Studies | N |

| 4 | Comparative European Politics | N |

| 5 | Millennium: Journal of International Studies | N |

| 6 | Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology | N |

| 7 | Terrorism and National Violence | N |

| 8 | Nationalism Papers: The Journal of Nationalism and Ethnicity | Y |

| 9 | Journal of Borderlands Studies | N |

| 10 | Polis | N |

Table A3.

“Top 10” Journals in Sociology & Political Science.

Table A3.

“Top 10” Journals in Sociology & Political Science.

| Sociology & Political Science | Relevant Article? (Y/N) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | European Journal of Political Research | N |

| 2 | Political Science Research Methods | N |

| 3 | Theory and Research in Social Education | N |

| 4 | Social Forces | N |

| 5 | European Sociological Review | N |

| 6 | Cities | N |

| 7 | Sociological Review | N |

| 8 | Journal of Sex Research | N |

| 9 | Political Geography | N |

| 10 | British Journal of Sociology | Y |

Table A4.

“Top 10” Journals in Education.

Table A4.

“Top 10” Journals in Education.

| Education | Relevant Article? (Y/N) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Journal of Educational Psychology | N |

| 2 | Theory and Research in Social Education | N |

| 3 | Child Development | N |

| 4 | British Journal of Educational Technology | N |

| 5 | Race, Ethnicity and Education | N |

| 6 | Journal of Youth and Adolescence | N |

| 7 | Comunicar | N |

| 8 | Journal of Literacy Research | N |

| 9 | Comparative Education | Y |

| 10 | Reading and Writing | N |

Table A5.

“Top 10” Journals in Economics, Econometrics & Finance.

Table A5.

“Top 10” Journals in Economics, Econometrics & Finance.

| Economics, Econometrics & Finance * | Relevant Article? (Y/N) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | European Journal of Health Economics | N |

| 2 | Globalisations | N |

| 3 | Journal of Cultural Heritage | N |

| 4 | Baltic Region | N |

| 5 | Review of Economic Perspectives | N |

| 6 | University of Pennsylvania Journal of International Law | N |

| 7 | Documenti Geografici | N |

| 8 | ||

| 9 | ||

| 10 | ||

* Only seven journals in this list came up in our Web of Science search.

Appendix B

This appendix outlines the filters applied in the Web of Science search.

- Behavioural sciences

- Clinical psychology & psychiatry

- Development studies

- Education

- Education & educational research

- Education, scientific disciplines

- Education, special

- Family studies

- Geography

- Humanities, multidisciplinary

- History & philosophy of science

- History of social sciences

- International relations

- Neuroscience & behaviour

- Philosophy

- Political science

- Political science & public administration

- Political science, public administration & development

- Psychiatry/psychology

- Psychology

- Psychology, applied

- Psychology, biological

- Psychology, clinical

- Psychology, development

- Psychology, educational

- Psychology, experimental

- Psychology, mathematical

- Psychology, multidisciplinary

- Psychology, psychoanalysis

- Psychology, social

- Social issues

- Social sciences, biomedical

- Social sciences, general

- Social sciences, interdisciplinary

- Social sciences, mathematical methods

- Sociology

- Sociology & social sciences

- Sociology/social sciences

- Anthropology

Appendix C

This appendix outlines the list of 66 ‘potentially relevant’ Web of Science journals.

Table A6.

List of potentially relevant Web of Science journals.

Table A6.

List of potentially relevant Web of Science journals.

| Journal Name | 2-Year IF | IF Year | IF Source | Relevant Article? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PSYCHOLOGY APPLIED TO LEGAL CONTEXT | 9.3 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EUROPEAN REVIEW OF SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY | 7.353 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| JOURNAL OF EUROPEAN PUBLIC POLICY | 7.339 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PERSONALITY | 5.838 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EUROPEAN PSYCHOLOGIST | 5.569 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF POLITICAL RESEARCH | 4.943 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EUROPEAN URBAN AND REGIONAL STUDIES | 4.49 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EUROPEAN POLITICAL SCIENCE REVIEW | 4.143 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS | 4.023 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| WEST EUROPEAN POLITICS | 3.96 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| SOUTH EUROPEAN SOCIETY AND POLITICS | 3.771 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EUROPEAN UNION POLITICS | 3.391 | 2021–2022 | 1 | Y |

| EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGY | 3.376 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EAST EUROPEAN POLITICS | 3.13 | 2020 | 2 | N |

| JOURNAL OF EUROPEAN SOCIAL POLICY | 3.063 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EUROPEAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW | 2.96 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EUROPEAN SOCIETIES | 2.923 | 2021–2022 | 1 | Y |

| EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF TEACHER EDUCATION | 2.864 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF DEVELOPMENTAL PSYCHOLOGY | 2.801 | 2021–2022 | 1 | Y |

| EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PSYCHOLOGY OF EDUCATION | 2.663 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| REVIEW OF EUROPEAN AND COMPARATIVE LAW | 2.541 | 2020 | 3 | N |

| EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF SOCIAL THEORY | 2.527 | 2021–2022 | 2 | N |

| EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH | 2.297 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| COMPARATIVE EUROPEAN POLITICS | 2.01 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY EDUCATION | 1.988 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| INNOVATION-THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF SOCIAL SCIENCE RESEARCH | 1.867 | 2020 | 3 | Y |

| METHODOLOGY-EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF RESEARCH | 1.865 | 2020 | 3 | N |

| EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW | 1.833 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EUROPEAN POLITICAL SCIENCE | 1.833 | 2021–2022 | 3 | N |

| EUROPEAN EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH JOURNAL | 1.787 | 2021–2022 | 1 | Y |

| EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF EDUCATION | 1.714 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF FUTURES RESEARCH | 1.679 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| SOUTHEAST EUROPEAN AND BLACK SEA STUDIES | 1.644 | 2020 | 3 | N |

| EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF CULTURAL STUDIES | 1.52 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EUROPEAN REVIEW | 1.52 | 2020 | 2 | N |

| JOURNAL OF EUROPEAN INTEGRATION | 1.483 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EUROPEAN POLICY ANALYSIS | 1.457 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EAST EUROPEAN POLITICS AND SOCIETIES | 1.43 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY EUROPEAN STUDIES | 1.355 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EUROPEAN LAW JOURNAL | 1.292 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EUROPEAN EARLY CHILDHOOD EDUCATION RESEARCH JOURNAL | 1.275 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF MIGRATION AND LAW | 0.929 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF POLITICAL THEORY | 0.828 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EUROPEAN REVIEW OF APPLIED PSYCHOLOGY-REVUE EUROPEENNE DE PSYCHOLOGIE APPLIQUEE | 0.822 | ? | 3 | N |

| EASTERN JOURNAL OF EUROPEAN STUDIES | 0.761 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EUROPEAN LAW REVIEW | 0.756 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| ANTHROPOLOGICAL JOURNAL OF EUROPEAN CULTURES | 0.75 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| JOURNAL OF CONTEMPORARY EUROPEAN RESEARCH | 0.694 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY | 0.582 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| REVIEW OF CENTRAL AND EAST EUROPEAN LAW | 0.389 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| EUROPEAN EDUCATION | 0.37 | 2020 | 2 | N |

| EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF LEGAL STUDIES | 0.25 | 2021–2022 | 1 | N |

| JOURNAL OF INDO-EUROPEAN STUDIES | 0.22 | 2020 | 2 | N |

| EUROPEAN PUBLIC LAW | 0.211 | 2021–2022 | AA | N |

| SLAVONIC AND EAST EUROPEAN REVIEW | 0.182 | 2021–2022 | AA | N |

| JOURNAL OF EUROPEAN STUDIES | 0.098 | 2021–2022 | AA | N |

| EUROPEAN INTEGRATION STUDIES | N/A | N/A | N/A | N |

| EUROPOLITY-CONTINUITY AND CHANGE IN EUROPEAN GOVERNANCE | N/A | N/A | N/A | N |

| COMPARATIVE SOUTHEAST EUROPEAN STUDIES | N/A | N/A | N/A | N |

| EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF EDUCATION AND PSYCHOLOGY | N/A | N/A | N/A | N |

| EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF INVESTIGATION IN HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY AND EDUCATION | N/A | N/A | N/A | N |

| EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PSYCHOLOGY OPEN | N/A | N/A | N/A | N |

| EUROPEAN LEGACY-TOWARD NEW PARADIGMS | N/A | N/A | N/A | N |

| INTERSECTIONS-EAST EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF SOCIETY AND POLITICS | N/A | N/A | N/A | N |

| ITINERARIO-INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL ON THE HISTORY OF EUROPEAN EXPANSION AND GLOBAL INTERACTION | N/A | N/A | N/A | N |

Appendix D

This appendix outlines the extraction template.

Appendix D.1. Study Characteristics

Title

Name of author(s)

Lead author contact details

Year of publication

Countr(ies) in which study was conducted

Characteristics of included studies

Aim of study (Research Questions, aims, hypotheses)

Study design

- -

- Response options: correlational, qualitative, longitudinal, experimental, cross-sectional, other

Study funding sources

Possible conflicts of interest for study authors

Has ethical approval been obtained?

- -

- Yes, no, unclear

Appendix D.2. Participants

Reporter (e.g., child, parent reporting on child’s behalf, teacher reporting on child’s behalf)

Inclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria

Method of recruitment of participants

- -

- Response options: online, through schools, phone, other

Total number of participants

Description of participants’ age

Sex (%) of participants

Country of origin of participants

Are there majority/minority ethnic groups within the study? If so, state here.

Appendix D.3. Methods

How was data collected?

survey, interview, experiment

How was European identity described and measured?

What antecedents of European identity were measured? (if applicable)

How were these antecedents described and measured? (if applicable)

What outcomes of European identity were measured? (if applicable)

How were these outcomes described and measured?

Was European identity considered in any other way?

Method of analysis

Appendix D.4. Results

Results pertaining to the link between antecedents and European identity (if applicable)

Results pertaining to the link between outcomes and European identity (if applicable)

Results pertaining to other analyses involving European identity

List covariates/mediators/moderators; results pertaining to them

Key conclusions drawn by study author(s)

Implications of finding(s), according to author(s)

Limitations of finding(s), according to author(s)

Author(s’) recommendations for further research

Appendix E

This appendix outlines the quality appraisal.

Table A7.

Quality Appraisal: Risk of Bias Assessment.

Table A7.

Quality Appraisal: Risk of Bias Assessment.

| Study | Selection Bias | Ethical Issues | Methodological Rigour |

|---|---|---|---|

| [30] | Low | Unsure | Unsure |

| [41] | Low | Unsure | Low |

| [42] | Low | Unsure | Low |

| [43] | Low | Unsure | Low |

| [44] | Low | Unsure | Low |

| [45] | Unsure | Unsure | Low |

| [46] | Low | Unsure | Low |

| [31] | Low | Low | Low |

| [47] | Low | Low | Low |

| [48] | Low | Unsure | Low |

| [32] | unsure | unsure | Low |

Note. “Low” refers to a low risk of bias (i.e., high study quality). “Unsure” is used when the criterium has not been discussed or is poorly discussed in the study. “High” refers to a high risk of bias (i.e., low study quality).

Appendix F

This appendix outlines the measures of European identity.

Table A8.

Measures of European identity.

Table A8.

Measures of European identity.

| Study | Measure of European Identity |

|---|---|

| [30] | Open-ended responses to the question ‘what does Europe mean to me personally’? |

| [41] | 3-item measure: ‘I am proud to live in Europe’; ‘I feel part of Europe’; ‘Indicate how strongly you identify with being European’ |

| [42] | Interview questions such as ‘to what extent do you see yourself as European?’; ‘How would you describe [your home country]’s relationship with Europe and the EU’; ‘What do you know about the European Union or Europe?’ |

| [43] | Positioning (categories which students drew upon to define their identity), integration (acceptance of people in a society—interethnic friendships and social inclusion) and politics (opinions about how societies are governed and who holds the power within these societies) |

| [44] | analysis of identity cards made by children |

| [45] |

|

| [46] | Three items, e.g., ‘I feel strong ties to my country/Europe’ (based on the Utrecht-Management of Identity Commitments Scale; U-MICS) [58] |

| [31] | Two items: ‘I feel strong ties toward Europe’ and ‘I am proud to be European’ |

| [47] | Two items: ‘I feel strong ties toward Europe’ and ‘I am proud to be European’ |

| [48] | Measures from the ICCS: “I am proud to live in Europe”, “I feel part of Europe”, “I am proud that my country is a member of the European Union”, and “I feel part of the EU” |

| [32] | Interviews coded for instrumental and cultural considerations about Europe |

Appendix G

This appendix outlines the measures of the constructs associated with European identity.

Table A9.

Measures of constructs associated with European identity.

Table A9.

Measures of constructs associated with European identity.

| Study | Construct | Measure |

|---|---|---|

| [30] |

|

|

| [41] | Perceptions of a (1) multicultural and (2) European dimension in school curriculum |

|

| [42] |

|

|

| [43] | N/A | N/A |

| [44] | N/A | N/A |

| [45] |

|

|

| [46] |

|

|

| [31] |

|

|

| [47] | Cross-border friendships | Single item: ‘How many of your friends live in other European countries?’ |

| [48] |

|

Objected benefits: Expected education level

|

| [32] | N/A | N/A |

References

- Gaertner, S.L.; Dovidio, J.F.; Anastasio, P.A.; Bachman, B.A.; Rust, M.C. The Common Ingroup Identity Model: Recategorization and the Reduction of Intergroup Bias. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 4, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, A.L.; Meltzoff, A.N. Childhood Experiences and Intergroup Biases among Children. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2019, 13, 211–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganann, R.; Ciliska, D.; Thomas, H. Expediting Systematic Reviews: Methods and Implications of Rapid Reviews. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varker, T.; Forbes, D.; Dell, L.; Weston, A.; Merlin, T.; Hodson, S.; O’Donnell, M. Rapid Evidence Assessment: Increasing the Transparency of an Emerging Methodology. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2015, 21, 1199–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recchi, E. Pathways to European Identity Formation: A Tale of Two Models. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2014, 27, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrano, J.D.; Gutiérrez, P. Nested Identities: National and European Identity in Spain. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2001, 24, 753–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceka, B.; Sojka, A. Loving It but Not Feeling It yet? The State of European Identity after the Eastern Enlargement. Eur. Union Polit. 2016, 17, 482–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaina, V.; Karolewski, I.P. EU Governance and European Identity. Living Rev. Eur. Gov. 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruter, M. On What Citizens Mean by Feeling ‘European’: Perceptions of News, Symbols and Borderless-ness. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2004, 30, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, K.A. Inclusive versus Exclusive: A Cross-National Comparison of the Effects of Subnational, National, and Supranational Identity. Eur. Union Polit. 2014, 15, 521–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fligstein, N.; Polyakova, A.; Sandholtz, W. European Integration, Nationalism and European Identity. JCMS J. Common Mark. Stud. 2012, 50, 106–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimoyiannis, A.; Boyle, E.A.; Tsiotakis, P.; Terras, M.M.; Leith, M.S. Exploring the Impact of the “RUEU?” Game on Greek Students’ Perceptions of and Attitudes to European Identity. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 834846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janoschka, M. Between Mobility and Mobilization—Lifestyle Migration and the Practice of European Identity in Political Struggles. Sociol. Rev. 2011, 58, 270–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kende, A.; Hadarics, M.; Szabó, Z.P. Inglorious Glorification and Attachment: National and European Identities as Predictors of Anti- and pro-Immigrant Attitudes. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 58, 569–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.K.; Corbett, B.; Maloku, E.; Tomašić Humer, J.; Tomovska Misoska, A.; Dautel, J. Strength of Children’s European Identity: Findings from Majority and Minority Groups in Four Conflict-Affected Sites. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2023, 20, 776–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaegen, S. What to Expect from European Identity? Explaining Support for Solidarity in Times of Crisis. Comp. Eur. Polit. 2018, 16, 871–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesdale, D. Children and Social Groups: A Social Identity Approach. In The Wiley Handbook of Group Processes in Children and Adolescents; Rutland, A., Nesdale, D., Brown, C.S., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-1-118-77316-1. [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R.; Leary, M. The Need to Belong: Desire for Interpersonal Attachments as a Fundamental Human Motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boston, C.; Warren, S.R. The Effects of Belonging and Racial Identity on Urban African American High School Students’ Achievement. J. Urban Learn. Teach. Res. 2017, 13, 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Schlenker, A. Cosmopolitan Europeans or Partisans of Fortress Europe? Supranational Identity Patterns in the EU. Glob. Soc. 2013, 27, 25–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, B.L.M.; Akiva, T. Motivating Political Participation Among Youth: An Analysis of Factors Related to Adolescents’ Political Engagement. Polit. Psychol. 2019, 40, 1039–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, M. English Children’s Acquisition of a European Identity. In Changing European Identities: Social Psychological Analyses of Social Change; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1996; pp. 349–369. [Google Scholar]

- Higley, E. Defining Young Adulthood. Ph.D. Thesis, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Krosnick, J.A.; Alwin, D.F. Aging and Susceptibility to Attitude Change. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1989, 57, 416–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agirdag, O.; Huyst, P.; Van Houtte, M. Determinants of the Formation of a European Identity among Children: Individual- and School-Level Influences. JCMS J. Common Mark. Stud. 2012, 50, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana-Vega, L.E.; González-Morales, O.; Feliciano-García, L. Are We Europeans? Secondary Education Students’ Beliefs and Sense of Belonging to the European Union. J. Youth Stud. 2021, 24, 1358–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cores-Bilbao, E.; Méndez-García, M.d.C.; Fonseca-Mora, M.C. University Students’ Representations of Europe and Self-Identification as Europeans: A Synthesis of Qualitative Evidence for Future Policy Formulation. Eur. J. Futur. Res. 2020, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DelGiudice, M. Middle Childhood: An Evolutionary-Developmental Synthesis. In Handbook of Life Course Health Development; Halfon, N., Forrest, C.B., Lerner, R.M., Faustman, E.M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-47141-9. [Google Scholar]

- Du Bois-Reymond, M. European Identity in the Young and Dutch Students’ Images of Germany and the Germans. Comp. Educ. 1998, 34, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoni, D.; Albanesi, C.; Ferreira, P.; Opermann, S.; Pavlopoulos, V.; Cicognani, E. Cross-Border Mobility, European Identity and Participation among European Adolescents and Young Adults. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 15, 324–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waechter, N. Instrumental and Cultural Considerations in Constructing European Identity among Ethnic Minority Groups in Lithuania in a Generational Perspective. Natl. Pap. 2017, 45, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SCImago SJR: Scientific Journal Rankings. Available online: https://www.scimagojr.com/journalrank.php?country=Asiatic%20Region&order=item&ord=desc&min=30&min_type=cd&year=2022 (accessed on 4 June 2024).

- Taylor, L.K.; Bähr, C. A Multi-Level, Time-Series Network Analysis of the Impact of Youth Peacebuilding on Quality Peace. J. Aggress. Confl. Peace Res. 2022, 15, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater Reliability: The Kappa Statistic. Biochem. Med. 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. (Eds.) JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: North Adelaide, NA, USA, 2024; ISBN 978-0-648-84882-0. Available online: https://jbi-global-wiki.refined.site/space/MANUAL (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Systematic Review Checklist. 2018. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/referencing/ (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. One Size Fits All? What Counts as Quality Practice in (Reflexive) Thematic Analysis? Qual. Res. Psychol. 2021, 18, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, A.M. Applying Critical Realism in Qualitative Research: Methodology meets Method. Int. J. Social Res. Methodol. 2017, 20, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brummer, E.; Clycq, N.; Driezen, A.; Verschraegen, G. European Identity among Ethnic Majority and Ethnic Minority Students: Understanding the Role of the School Curriculum. Eur. Soc. 2022, 24, 178–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faas, D. Turkish Youth in the European Knowledge Economy. Eur. Soc. 2007, 9, 573–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faas, D. Reconsidering Identity: The Ethnic and Political Dimensions of Hybridity among Majority and Turkish Youth in Germany and England. Br. J. Sociol. 2009, 60, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healy, M.; Richardson, M. Images and Identity: Children Constructing a Sense of Belonging to Europe. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 2017, 16, 440–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, V.; Katona, Z. National and Supranational Identities and Ingroup-Outgroup Attitudes of Hungarian Adolescents. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 15, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landberg, M.; Eckstein, K.; Mikolajczyk, C.; Mejias, S.; Macek, P.; Motti-Stefanidi, F.; Enchikova, E.; Guarino, A.; Rammer, A.; Noack, P. Being Both—A European and a National Citizen? Comparing Young People’s Identification with Europe and Their Home Country across Eight European Countries. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2018, 15, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G.; Cicognani, E.; Mazzoni, D. Cross-Border Friendships and Collective European Identity: A Longitudinal Study. Eur. Union Polit. 2019, 20, 649–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaegen, S.; Hooghe, M. Does More Knowledge about the European Union Lead to a Stronger European Identity? A Comparative Analysis among Adolescents in 21 European Member States. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2015, 28, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehrson, S. Argumentative Contexts of National Identity Definition: Getting Past the Failures of a Universal Ethnic–Civic Dichotomy. In Liberal Nationalism and Its Critics; Gustavsson, G., Miller, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 133–152. ISBN 978-0-19-884254-5. [Google Scholar]

- Savvides, N. Developing a European Identity: A Case Study of the European School at Culham. Comp. Educ. 2006, 42, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, K.A. Personality’s Effect on European Identification. Eur. Union Polit. 2016, 17, 429–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovidio, J.F.; Gaertner, S.L.; Pearson, A.R.; Riek, B.M. Social Identities and Social Context: Social Attitudes and Personal Well-Being. In Social Identification in Groups (Advances in Group Processes); Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2005; Volume 22, pp. 231–260. [Google Scholar]

- Ranta, R.; Nancheva, N. Unsettled: Brexit and European Union Nationals’ Sense of Belonging. Popul. Space Place 2019, 25, e2199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blue Star Programme. The Blue Star Programme|Let’s Get Creative About Europe! Available online: https://www.bluestarprogramme.ie/ (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- International Rescue Committee. 110 Million People Displaced around the World: Get the Facts. Available online: https://www.rescue.org/eu/article/110-million-people-displaced-around-world-get-facts (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- UNHCR. Situation Ukraine Refugee Situation. Available online: https://data.unhcr.org/en/situations/ukraine (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Simmons, R.W.; Stokes, B.; Simmons, K. Europeans Not Convinced Growing Diversity Is a Good Thing, Divided on What Determines National Identity; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Meeus, W. Studies on Identity Development in Adolescence: An Overview of Research and Some New Data. J. Youth Adolesc. 1996, 25, 569–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottfredson, G.D.; Czeh, E.R.; Lambert, J.; Friend, R.; Jones, E.M. The School Diversity Inventory (SDI). Available online: https://education.umd.edu/sites/default/files/uploads/SDI_SampleStu.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Keating, A. Are Cosmopolitan Dispositions Learned at Home, at School, or through Contact with Others? Evidence from Young People in Europe. J. Youth Stud. 2016, 19, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, C.; Molcho, M.; Boyce, W.; Holstein, B.; Torsheim, T.; Richter, M. Researching Health Inequalities in Adolescents: The Development of the Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Family Affluence Scale. Soc. Sci. Med. 2008, 66, 1429–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amnå, E.; Ekström, M.; Kerr, M.; Stattin, H. Codebook: The Political Socialization Program; Youth & Society at Örebro University: Örebro, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, M.; Zani, B. Political and Civic Engagement. Multidisciplinary Perspectives; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, D.; Sturman, L.; Schulz, W.; Burge, B. ICCS 2009 European Report ICCS 2009 European Report—Civic Knowledge, Attitudes, and Engagement among Lower-Secondary Students in 24 European Countries; IEA: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).