Abstract

Uttarakhand is situated on the southern slope of the world’s youngest (geo-dynamically sensitive) mountain system, “the Himalayas”. Owing to rapid deforestation in the planar districts due to an increase in infrastructural growth, the wildlife–livestock–human interface has blurred. This has increased the chances of contact exposure of wild boars to humans and domestic animals. The study identifies the location of pig rearers and their pig rearing practices, with its ecological effects, and also studies the mitochondrial DNA diversity using a control region from the 68 samples collected from the surveyed household. Analysis showed that 60.7%, 10.7% and 21.4% of the households raised pig near seasonal streams (slum settlements), the residential areas and near the forest, respectively. Furthermore, 28.6% maintained breeding boar of feral origin and 96.94% followed semi-intensive pig rearing practices; hence human settlements have stayed in close association with pigs (domestic and wild) and other domestic animals. The possibility of the emergence of zoonotic and non-zoonotic disease and its easy transmission to humans has become more prominent in the urban setting. A total of 18 haplotypes were observed with 34 segregating sites in 68 analyzed sequences. The high level of haplotype diversity and nucleotide diversity suggested an increase in crossbreeding among the species.

1. Introduction

Unlike other domesticated animal species, the abundance of domestic pigs in a particular region is influenced by the religion, culture, and traditions of people within the region and their respective association with pork consumption. The worship and significance of wild boar in India have been seen since time immemorial [1], however, on the question of pig rearing, the scenario depends on the other aspect of Hinduism called the caste system, which is the oldest form of surviving social stratification and its effect cannot be ignored in modern society. According to the traditional caste system, the lower caste prefers pig rearing. Hence, in India, pigs are raised mostly by scheduled caste and tribes to maintain their social identity and traditional culture [2]. The present study aims to: (1) identify the location of pig rearers and their pig rearing practices in urban districts of Uttarakhand and analyze its ecological implications to the urban landscape and human settlement, and; (2) investigate the mtDNA diversity among the domestic pig of the study area.

2. Methods

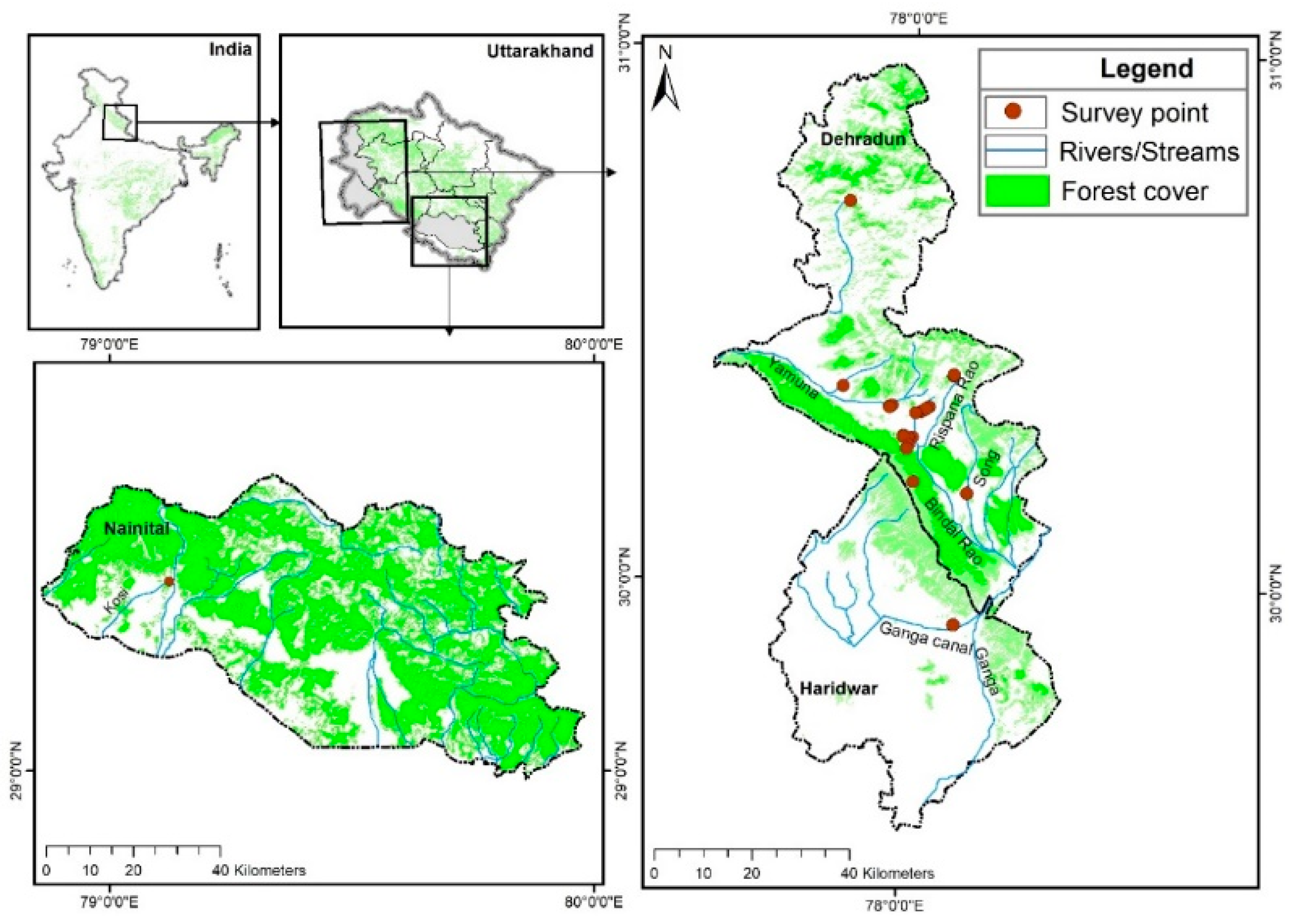

Household Survey and Rapid appraisals approach was adopted as “survey and monitoring tools” to identify more geographical locations in Uttarakhand, where pig rearers were localized [3]. In total, 28 households (HH) (25 in Dehradun, 2 in Haridwar, and 1 in Nainital), were interviewed by preparing a semi-structured questionnaire from March 2019–December 2019 in the urban districts of Uttarakhand. The geographical position of each participating family was recorded using the Android based software, Google Maps.

2.1. Sample Collection, DNA Extraction, Amplification and Sequencing

Non-invasive biological samples (hairs and tissues) were collected from 68 un-relatable pigs from the surveyed household for mtDNA studies. Genomic DNA was extracted using DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) protocol and the amplification of approximately 419 bp mtDNA hypervariable control region was recorded using control region-specific primer pair [4].

2.2. Sequence Data Analysis

Sequences were confirmed using the BLAST tool on NCBI (http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ accessed on 1 December 2021) and were clean and edited with SEQUENCHER® version 4.9 (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). We obtained 2826 cleaned and aligned global control region sequences (404 bp) representing Sus scrofa from GenBank. The global control region sequences were aligned with 68 samples of Uttarakhand using the CLUSTAL W algorithm [5] in program MEGA X [6]. Haplotype (Hd) and nucleotide diversities (Pi) were calculated using program DnaSP v.5.10 [7]. Haplotypes were derived by removing non-informative sites, and gaps were considered. The haplotypes sharing with global sequences were reconstructed using the median-joining network in PopART v.1.7 [8].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Map Plotting Analysis

A total of 60.7% of households raised pigs near slum settlements (Figure 1) that had inadequate sanitation, and these unhygienic environments pose a risk to animal health and human health. Of the households interviewed, 21.4% raised pigs near forest areas, increasing the chances of contact exposure of wild boars, which itself harbors several viruses, bacteria, and parasites diseases. Thus, the transmission of pathogens between wild boars and humans becomes more conspicuous in highly populated districts, either by consumption of wild boar meat (which has been reported in Uttarakhand) or through cross-breeding of the domestic population with the wild population.

Figure 1.

Map showing the location of surveyed household in the study area of Uttarakhand.

3.2. Pig Husbandry Practices in Uttarakhand

Households kept 2–4 adult sows and 1–3 hybrid boars with their piglets in their herd (Figure 2a–c). They identified the breeds as indigenous and mixed parentage of indigenous crossed with the exotic breed and putative crossed with a wild pig. A total of 28.6% pig rearers maintained probable breeding boar of feral origin in secrecy due to its easy availability and high sale value (Figure 2d). The combination of farrow to finish and piglet production systems are observed in 85.7% of the households surveyed. Only 14.3% of the households practiced fattener production. The major rearing pattern observed in the study area was a semi-intensive system (96.94%) (Figure 2e), followed by an extensive system (3.57%) (Figure 2f). These systems need less capital investment, but disease incidences and parasite infestations are high.

Figure 2.

(a) Pig herd in Ramnagar (Nainital district of Uttarakhand) (b) Pig herd of mixed parental origin observed in Chandrabani (Dehradun district of Uttarakhand) (c) Pig herd in Jwalapur (Haridwar district of Uttarakhand) (d) Possible hybridized feral origin or boar piglet for sale or mating purpose (e) Semi-intensive system of pig management with housing facility (all the pen is made of brick with tin as a roof within the house premises) (f) Extensive system of pig management with no housing facility.

3.3. Haplotype Analysis and Sequence Variability

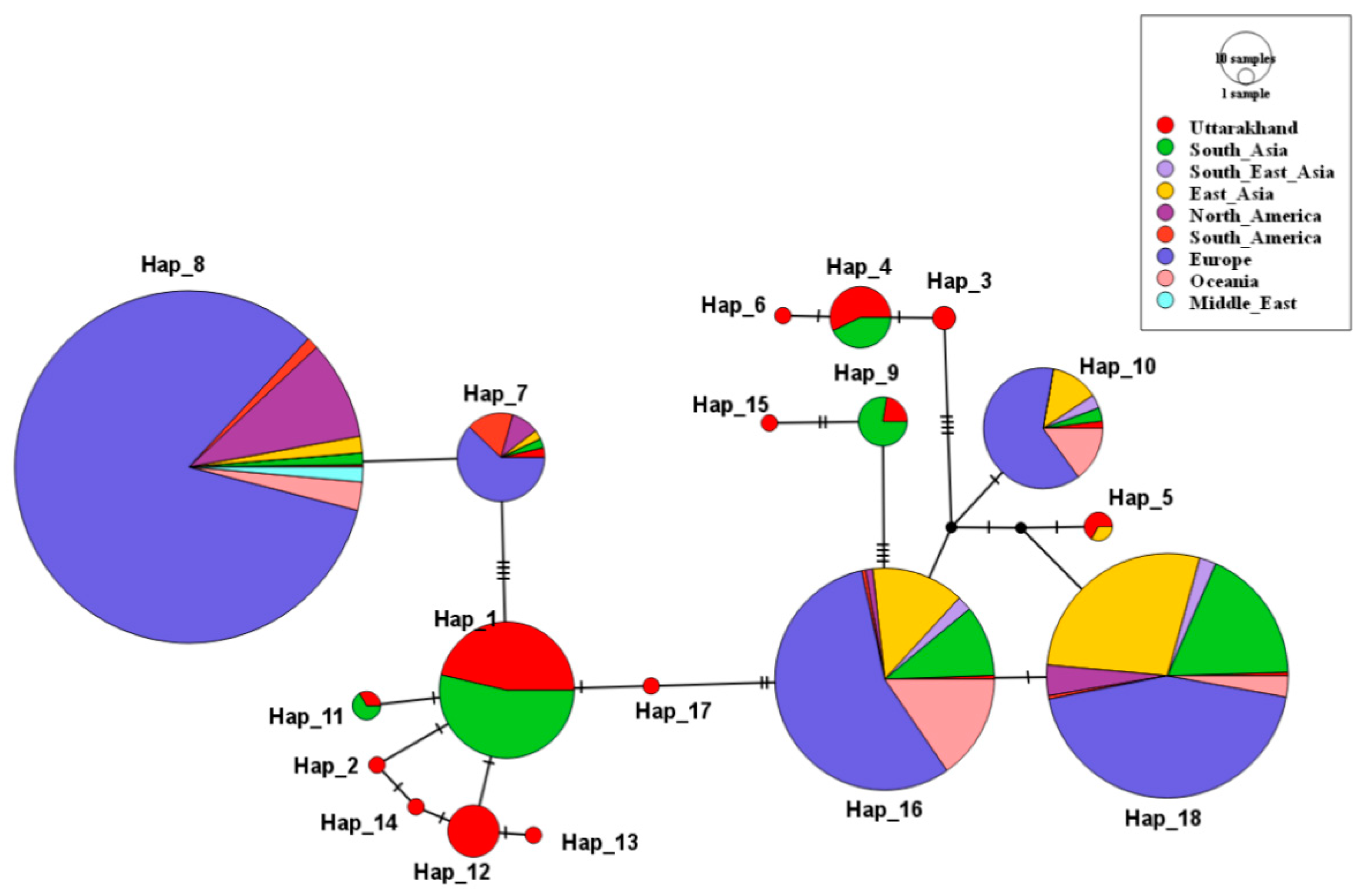

A total of 18 mtDNA haplotypes with 34 segregating sites in 68 analyzed sequences were observed. The haplotype (gene) diversity for the analyzed sequence were Hd = 0.749 (0.0024) and nucleotide diversity was Pi = 0.0132 (0.002). Eighteen haplotype obtained from the Uttarakhand sample shared the haplotype with n = 998 sequences from the GenBank. Figure 3 shows the region-wise haplotype sharing with the global sequences.

Figure 3.

Median-joining haplotype network of 18 haplotypes identified in Uttarakhand sample and its sharing with global sequences (n = 998). Circle size represents the frequency of individuals, and color defines the region-wise populations. Small black circles represent median vectors. Mutational steps are shown by bar on the respective branches.

The Hap_1 consists of 32 modern sequences of Uttarakhand that share its haplotype with the domestic breed (Richengang) of Bhutan [9] and the Indian wild population [10] from GenBank. Hap_1 has multiple connections, and by forming a star-like pattern, suggests that this haplotype is older and is widely distributed among the domestic pigs of Bhutan and Northern/Central India. Moreover it also shares the haplotype with the museum sample of the Indian wild population of Kashmir and the wild and domestic population of West Bengal [10]. This Haplotype is widely found in samples of Dehradun and Nainital districts of Uttarakhand.

Hap_11 has only one sample from Uttarakhand share its haplotype with domestic pigs from Nepal [9]. Hap_12 have 10 sequences, which include a sequence from the Haridwar District of Uttarakhand and Hap_2, Hap_14, Hap_13, Hap_17 have only one sequence each of a single area of Dehradun near river Song, and shows that these are a recently evolved population and their carriers are still localized in its evolved areas.

Hap_9, which has two sequences from the Naintal Districts of Uttarakhand, shared the haplotype with a museum specimen of wild pig from Nepal and India [10], and also from wild pigs from Northern and Central India. Hap_15, which has also recently evolved, does not share its haplotype with any sequence.

Hap_4 includes seven sequences of Uttarakhand that share its haplotype with Bhutan’s domestic breed, Machay Madhuri, and Nepal’s domestic pig breed. Hap_3 and Hap_6 contains only Uttarakhand sequences. Hap_7, 8, 10, 16, 18 each contain a single sequence of Uttarakhand and are globally distributed.

Hence the results show a possibility of maternal gene flow between India, Bhutan and Nepal.

4. Conclusions

The findings from the small representation of pig rearers in Uttarakhand suggest that the wild cross with domestic are included in the herd due to their easy availability, disease resistance, meat preference, and medicinal values; hence, they come in close contact with humans and other livestock species and these interactions create a potential threat for disease spill over from wild pigs to humans and other livestock species. The intensity of the risk of transmission becomes more profound with an increase in urbanization and anthropogenic influence beyond the carrying capacity of the area’s ecological system. The government often neglects public health policies while planning for urban development. This neglect poses a higher risk for both zoonotic and non-zoonotic disease to the population living near slums and informal settlements. Hence these settlements can become an epicenter for the outbreak of infectious disease and, due to pigs roaming in these areas, the chances of zoonotic disease will also increase. The location of the herd and its foraging should be strictly monitored. A report of multiple outbreaks of ‘Human Trichinosis’ caused by eating undercooked wild boar meat has been reported [11], hence sensitization of the local community for avoiding the wild animal meat should be developed.

The mitochondrial diversity is high and eight haplotype are unique to Uttarakhand, hence efforts should be made to conserve the haplotypes and classify the phenotypic characteristics of the indigenous breed.

Funding

This research was funded by the Department of Science and technology under the Women Scientist Scheme-A (WOS-A) scheme with project number SR/WOS-A/LS-304/2018.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Director and Dean WII for their support. Surya Prakash Sharma is thanked for helping in map preparation and field assistants Rakesh Kumar and Anil Kumar.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Dornadula, C. Geomythology of India. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2007, 273, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, H.N.C. Status Evaluation in the Hindu Caste System. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. Great Br. Ireland 1954, 84, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Surveying and Monitoring of Animal Genetic Resources. FAO Animal Production and Health Guidelines; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan, C.N.; Monfort, S.L.; Gaur, A.; Singh, L.; Sorenson, M.D. Phylogeography and conservation genetics of Eld’s deer (Cervus eldi). Mol. Ecol. 2003, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, J.D.; Gibson, T.J.; Plewniak, F.; Jeanmougin, F.; Higgins, D.G. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 4876–4882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kumar, S.; Stecher, G.; Li, M.; Knyaz, C.; Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 1547–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Librado, P.; Rozas, J. DnaSPv5: A software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1451–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leigh, J.W.; Bryant, D. PopART: Full-feature software for haplotype network construction. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2015, 6, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nidup, K.; Tshering, D.; Wangdi, S.; Gyeltshen, C.; Phuntsho, T.; Moran, C. Farming and biodiversity of pigs in Bhutan. Anim. Genet. Resour. 2011, 48, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larson, G.; Dobney, K.; Albarella, U.; Fang, M.; Matisoo-Smith, E.; Robins, J.; Lowden, S.; Finlayson, H.; Brand, T.; Willerslev, E.; et al. Worldwide phylogeography of wild boar reveals multiple centers of pig domestication. Science 2005, 307, 1618–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sethi, B.; Butola, K.S.; Arora, B.; Kumar, Y.; Suri, V. Human trichinosis in remotes of Uttarakhand, India. Indian J. Med. Sci. 2010, 64, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).