Abstract

This paper explores the current use of crypto-assets for payments, focusing mostly on unbacked crypto-assets, while selectively referring to stablecoins. Although some specific characteristics of crypto-assets, such as their price volatility and unclear legal settlement, render them unsuitable for payments, the rapid technological and regulatory developments in the area of crypto-assets-based payments justify monitoring developments in this area. We therefore try to answer the research questions of which/why/how/where/by whom crypto-assets are used for (retail) payments. We analyse and describe a variety of ways in which crypto-assets are used for making payments, focusing on the period from 2019 to 2023 in Europe and worldwide, based on the publicly available statistical data and literature. We identify and exemplify the main use cases, payment methods, DeFi protocols, and payment gateways, and analyse payments with crypto-assets based on location and market participants. In addition, we describe and analyse the integration of crypto-assets into existing commercial payment services. Our work contributes to understanding the shifting domain of crypto-assets-based payments and provides insights into the monitoring of relevant developments via various dimensions that need to keep being explored, with the objective of contributing to the maintenance of the integrity and stability of the financial ecosystem.

JEL Classification:

E42; O30; O31; D100

1. Introduction

While crypto-assets were originally created with the intention of serving as a means of payment that dispenses with intermediaries, their use has not yet considerably extended beyond the crypto-asset environment. As mainstream attention to crypto-assets grows, we could potentially see an increase in the use of (certain types of) crypto-assets for payments. Such an increase could potentially have multiple consequences in the financial ecosystem and therefore should be studied. Indeed, the role of crypto-assets in the payments ecosystem has attracted a lot of attention and different views [1,2,3,4]. It is therefore important to keep track of the developments and trends in this area.

Advances in the relevant regulatory frameworks should also be considered. A prominent case is the entry into force of the Regulation on markets in crypto-assets (MiCAR) [5] in the European Union in June 2023, with full applicability in 2024, which could potentially impact the use of crypto-assets (in particular stablecoins—a category of crypto-assets that purports to maintain a stable value) for making payments. The MiCAR already considers the possibility of the potential wider adoption of stablecoins by retail holders and the risks and challenges that such a development would raise. Recital 5 of the MiCAR states that “It is, however, possible that types of crypto-assets that aim to stabilise their price in relation to a specific asset or a basket of assets could in the future be widely adopted by retail holders, and such a development could raise additional challenges in terms of financial stability, the smooth operation of payment systems, monetary policy transmission or monetary sovereignty”. It is, therefore, important to also closely monitor and analyse crypto-asset-related developments in the field of payments and thus address the gaps in understanding the real-world use of crypto-assets for payments. However, such monitoring is often hampered significantly by the lack of official statistics and other high-quality data on the use of crypto-assets for payments.

Our motivation is to contribute to addressing the gaps in understanding this important topic as, on the one hand, developments in the field of crypto-asset-based payments are occurring rapidly and, on the other hand, there is a lack of necessary official data. We aim to create a clear picture of the current status of payments using crypto-assets, as well as identify the trends in this field and predict potential future developments. The existing research on the use of crypto-assets for payments has been based so far on qualitative methodologies and surveys, such as the works of Al-Amri et al. [6], Kayani et al. [7], and Busse et al. [8] and in a more general concept of crypto-assets adoption [7,9]. We therefore try to fill in the gap regarding the lack of data-based analysis. In order to achieve this, and considering the lack of relevant official data, we rely on publicly available and voluntarily provided data to analyse the current use of crypto-assets for payment transactions during the period from 2019 to 2023, focusing mostly on unbacked crypto-assets, while referring to crypto-assets that are stablecoins only where specifically mentioned. We consider that the use of stablecoins may need a further and separate analysis in relation to the MiCAR adoption [10]. Special attention is paid to the trends and developments in European countries. The main research questions are as follows: (a) Which crypto-assets are used for (retail) payments? (b) Why and how are crypto-assets are used for (retail) payments? (c) Where are crypto-assets used for (retail) payments? (d) Who uses crypto-assets for (retail) payments? The answers to these questions can offer an initial evaluation as well as a solid basis for further analysis.

The rest of the paper is thus organised as follows: In Section 2, we present the various categories of crypto-assets that can be used for payments (the “which” question), and the main use cases of crypto-assets for payments which show the motives for their use (the “why” question). Section 3 describes crypto-asset payment methods (the “how” question). Section 4 provides novel payment indicators for crypto-asset payments by economic sector and geographical area, to try to answer the question about where crypto-assets are used for retail payments. Section 5 attempts to answer the question of who uses crypto-assets for making payments. In Section 6, the paper provides insights into how crypto-assets are being integrated into existing commercial payment services. The conclusions follow in the final Section 7.

2. Crypto-Assets and Their Use Cases for Payments

The MiCAR defines crypto-assets as digital representations of a value or of a right that can be transferred and stored electronically using distributed ledger technology or similar technology (art. 3.1(5) MiCAR), noting that the representations of value include the external, non-intrinsic value attributed to a crypto-asset by the parties concerned or by market participants, meaning the value is subjective and based only on the interests of the purchaser of the crypto-asset (recital 2 of the MiCAR). While the MiCAR does not use the term stablecoin, it is generally understood that only asset-referenced tokens (ARTs) and electronic money tokens (EMTs) qualify as stablecoins, contrary to crypto-assets other than ARTs and EMTs, so-called unbacked crypto-assets. The MiCAR defines ARTs as a type of crypto-asset that is not an electronic money token and that purports to maintain a stable value by referencing another value or right or a combination thereof, including one or more official currencies (article 3.1(6) MiCAR). EMTs are a type of crypto-asset that purport to maintain a stable value by referencing the value of one official currency. The definition of crypto-assets in the MiCAR encompasses ARTs, EMTs, and crypto-assets that are not ARTs or EMTs. While the first two categories are generally referred to as stablecoins, the latter category is generally referred to as unbacked crypto-assets.

The broad variety of available crypto-assets unlocks several use cases for payments, such as payments with crypto-assets in e-commerce, stores, peer-to-peer transactions, payments for tokenised assets (such as digital bonds and non-fungible tokens (NFTs)), and a combination of other novel use cases that may cater to specific needs, such as micropayments and streaming payments. The following sections describe the main use cases for payments using crypto-assets.

2.1. Micropayments

There is currently no agreed upon definition of a micropayment. However, it generally refers to payments of very low value that are usually made in an online environment [11]. Enthusiasts refer to an up-and-coming use case for micropayments, machine-to-machine payments, whereby internet of things (IoT) devices can communicate payments autonomously. An example would be an electric car that automatically pays for the exact amount of time it parks in a certain location. These enthusiasts argue that the conventional payments landscape is not particularly well suited to these types of low-value payments due to the associated volumes, costs, and processing fees of the individual payment transactions. They assume that blockchain technology and other distributed ledger technologies (DLTs), which refer to technological infrastructure and protocols that allow for simultaneous access, validation, and record updating across a networked database [12], such as a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG)-based ledger [13], have the potential to enable large-volume, low-value digital micropayments using crypto-assets. There are multiple DLT platforms on the market that seek to achieve efficient crypto-asset-based micropayments. Some examples of these include the following:

- IOTA [14]: This crypto-asset, launched in 2016, seeks to enable micropayments by using a DAG-based DLT. As the IOTA network does not use mining to validate transactions, this facilitates a feeless transaction model. The IOTA Foundation has presented some micropayment use cases, such as peer-to-peer (P2P) energy trading, for which its real-world adoption appears limited at present.

- Brave [15]: This is an opensource browser that offers its users the option to be paid for the ads that are displayed in the browser. For this purpose, a crypto-asset called the Basic Attention Token was created. The browser reported 65 million monthly active users and 10.6 million wallets in December 2023.

- The Lightning Network [16]: This is a Layer 2 payment protocol that allows for micropayments in bitcoin (see Appendix C). We note that a Layer 2 (or rollup) is a separate layer that extends a Layer 1 blockchain by executing multiple transactions and submitting them as a single transaction into the Layer 1 blockchain. By submitting the transaction data into Layer 1, rollups -leverage the security characteristics of the Layer 1. The use of rollups could reduce transaction costs, which could, in turn, allow for the better use of micropayments.

Crypto-assets could enable growth in the area of micropayments. However, most crypto-assets that support micropayments are still in the investigation phase. The adoption of these types of crypto-assets in the real world looks to remain limited at this point. This may be due to the blockchain trilemma: a crypto-asset must compromise on either the decentralisation, security, or scalability of a blockchain. As a result, if a blockchain is to perform a lot of (low-value) transactions at the same time, the hardware requirements of the nodes will go up, which leads to centralisation. One of the solutions for scaling blockchains is to have several layers of blockchains (Layer 2s), instead of a single one.

2.2. Streaming

Another use case where crypto-assets are used for payments is via DeFi payment applications. DeFi payment applications enable crypto-asset streaming. This is where payments are streamed continuously or regularly to a receiver based on a specified rate (the amount of crypto-assets transferred per second) and timeline (the start and stop time of a stream). The rate and timeline are setup in smart contracts. Crypto-assets aside, money streaming is already possible via existing banking arrangements, where automatic transfers of funds enable regular, periodic transfers between two (or more) accounts without having to issue further instructions after the initial instructions and authorisation. However, decentralised money streaming protocols, such as Sablier [17] and LlamaPay [18] (see Appendix C), enable crypto-asset streaming in a more granular way. They facilitate mainly continuous payments in relation to a provided service, such as salaries, where employees receive crypto-assets in real time for their work instead of on a monthly basis in fiat money, donations, and subscriptions.

2.3. Instant Payments/Instant Settlement

The advocates of crypto-assets emphasize their use for making payments with an instant or atomic settlement of transfers on a distributed ledger, including blockchains. This use case would be relevant, in particular, for the possibility of settling transactions in tokenised assets with delivery versus payment in real time on the same platform. Instant settlement, however, refers to the technical settlement of a transfer, at best. The legal settlement of transfers in crypto-assets is uncertain, and may not be settled instantly with legal finality. In Europe, for example, such transfers do not fall under the Settlement Finality Directive [19]. Blockchains are based on the “code is law” principle. Blockchains, therefore, have no visibility within the underlying legal framework that is applicable between the parties. The Lightning Network [16] and Flexa [20] are examples of decentralised payment software protocols that use blockchains and enable instant payments (see Appendix C).

2.4. Cross-Border Payments

A cross-border payment is a transaction where the payer and the payee are located in different jurisdictions. It often involves cross-currency conversion. These types of payments are currently complex in nature and they often prove to be expensive because of the involvement of multiple intermediaries, jurisdictions, time zones, and divergent regulatory frameworks [21]. Cost is not the only factor that causes friction in cross-border payments. These payments are much slower, less accessible, and more opaque compared to domestic payments. As part of the broader G20 Roadmap for Enhancing Cross-border Payments, the BIS Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (CPMI) assessed whether and how the use of stablecoin arrangements, if properly designed and regulated, and compliant with all relevant regulatory requirements, could enhance cross-border payments. The CPMI identified multiple possible opportunities that could arise from the use of stablecoin arrangements for cross-border payments, including the following [22]: (i) reducing costs, as a stablecoin could shorten long transaction chains by reducing the number of intermediaries; (ii) increasing speed, as the DLTs that underpin most stablecoins, are, by definition, available 24/7; (iii) expanding the set of payment options, as stablecoins could be an alternative digital option available for individuals who want to send or receive remittances; and (iv) improving transparency, as stablecoins would facilitate the better traceability of payment statuses in real time by making use of public DLTs.

Nevertheless, several challenges concerning the use of stablecoins for cross-border transactions have been identified ([22,23]). These challenges include the following: (i) the lack of a sound governance structure; (ii) concentration and monopoly risks, which could lead to a lack of competition and consumer protection; (iii) issues with data privacy, anti-money laundering, and countering the financing of terrorism; (iv) divergent regulatory frameworks across jurisdictions; (v) potential fluctuations in exchange values away from the par; and (vi) the inconsistent availability of on- and off-ramps that would allow stablecoin users to easily convert them to cash or commercial bank money held at regulated financial institutions.

Although there are some ongoing initiatives (see Section 7) at the time of the writing of this paper, no stablecoin exists that addresses all the challenges associated with cross-border payments in such a way that it would outperform existing cross-border payment rails [22]. It still remains unclear whether a future stablecoin would be able to achieve a setup where the benefits of executing cross-border payments via a stablecoin would outweigh the associated drawbacks. Moreover, the alternative of a CBDC (Central Bank Digital Currency) for the same purpose, which would inherently resolve many of the aforementioned drawbacks, emphasizes this open question.

3. Payment Methods, DeFi Protocols, and Gateways

In this section, we present the methods used to pay with crypto-assets and the specific systems that facilitate the use of these methods, specifically DeFi payment protocols and payment gateways.

3.1. Methods

There are several ways to pay with crypto-assets. First, consumers can pay for goods and services using a cPOS terminal. In this case, depending on the setup and what both parties to the transaction agree, the merchant can receive either crypto-assets in an electronic wallet or fiat currency.

Second, crypto-assets can be held in electronic wallets (digital wallets) with a payment function and then transferred directly between two wallets without the need of a terminal, where such a transfer would mark the payment for a transaction between a customer/payer and a retailer/payee, if they so agree. In such a transaction, the transfer of crypto-assets, constituting a value transfer in the eyes of the two subjects involved, occurs without the intervention of financial intermediaries. Once such a transfer is validated by the community of validators on the blockchain, the transfer is irreversible from an operational, IT perspective (unless a fork occurs). From a legal perspective, however, settlement finality would not be ensured until at least midnight of the day of the transfer. This is because transfers of crypto-assets are not exempt from the zero-hour rule [24] in those countries whose insolvency laws include this rule. The prerequisite for using crypto-assets to pay for transactions in this way is an activated digital wallet, which constitutes the tool for managing and storing one’s crypto-assets. Various payment protocols have been developed to allow for the transfer of crypto-assets between two market participants (see Section 3.2). Wallets are also used in crypto payment gateways, which are platforms that aim to facilitate crypto payments in the retail sector (see Section 3.3), bringing retailers and customers together. Digital wallets are also used in various existing European payment solutions, such as iDEAL [25], Klarna [26], Swish [27], and Bankgiro [28].

A third way to pay with crypto-assets is to use cards. In general, crypto-asset payment cards work as follows: upon initiation of a payment order, this triggers a mechanism managed by a relevant exchange for the instant conversion between the customer’s crypto-asset portfolio and the fiat currency. Conversion fees are charged by the exchange. This is called off-ramping, where the crypto-asset is converted to fiat money via card programs. After the conversion, the fiat money circulates on the card network before reaching the beneficiary of the payment. The exchanges, rather than any of the other parties involved, manage the crypto-assets themselves. This payment method allows the holders of crypto-assets to pay in fiat money while using their crypto-assets in all shops that are part of the card network. The management of AML-CFT compliance for this payment method is not clear, but appears to mainly rely on the crypto exchange, while the payment firm only conducts due diligence on the crypto exchange. Because of this lack of clear AML-CFT compliance, some partnerships have been terminated. For example, Mastercard ended its partnership with the crypto exchange Binance [29] in August 2023, while VISA has stopped issuing new Binance cards in the European market. As a result, the Binance card program in the European Economic Area ended on 20 December 2023 [30]. Nevertheless, VISA has partnered since 2021 with multiple crypto exchanges, resulting in a payment volume of USD 3 billion at the end of 2023 [31]. The Revolut card [32] also supports payments with crypto-assets. Revolut customers can link a Revolut card to any of their crypto-asset accounts. Upon the initiation of a payment order, their crypto-assets are automatically exchanged for the equivalent fiat amount via a partnership with a crypto exchange. This automatic exchange must be based on a preliminary authorisation and standing order from the Revolut customer to the crypto-asset exchange to exchange crypto-assets into fiat money whenever a payment order is initiated. Standard exchange fees apply to these transactions. However, the “link card to crypto pocket” feature is currently available only in the UK and Switzerland. Furthermore, one can receive crypto-assets sent by another Revolut user via the Revolut platform, allowing for payments in crypto-assets. Regarding the crypto-asset management rates, Revolut streams the prices from the exchanges they have partnered with and calculates a volume-weighted average price. The derived rate considers additional factors, such as market depth and volatility.

Fourth, crypto-assets can be used for making payments via payment accounts by instructing the customer’s own bank. Some crypto payment platforms are integrated with bank accounts, allowing users to link their crypto wallets to their bank accounts and convert between fiat and crypto-assets. Some examples of crypto payment platforms that support payment accounts include the following:

- BitPay [33] allows businesses and individuals to receive and send crypto payments. BitPay also offers BitPay cards, which are prepaid MasterCards. Users can load their cards with crypto-assets and spend the crypto-assets (converted into fiat money) wherever MasterCards are accepted. Users can also withdraw money from ATMs and transfer money to their bank accounts using the BitPay app.

- Wirex [34] is a platform that combines crypto-assets and existing currencies in fiat money into a single account. Users can buy, sell, exchange, and store over 20 crypto-assets and fiat currencies using the Wirex app and card. The services and features supported by Wirex depend on the country and the applicable national legal framework. In some countries, such as the UK and the USA, Wirex offers cashback rewards (Cryptoback), bank accounts, and money transfer services. Users can link their Wirex accounts to their bank accounts.

- Crypto.com [35] is a platform that aims to accelerate the adoption of crypto-asset payments. Users can buy, sell, store, and earn over 100 different crypto-assets and fiat currencies through the Crypto.com app and cards. Crypto.com is a lending, gambling, and investment platform. Users can link their Crypto.com accounts to their bank accounts.

Fifth, even though not directly used for payments, consumers can use crypto ATMs (cATMs) to buy, sell, or send crypto-assets to others using cash, cards, or apps. Figures and charts on cATMs are provided in Section 4, while a description of the functioning of cATMs can be found in Appendix A.

3.2. DeFi Payment Protocols

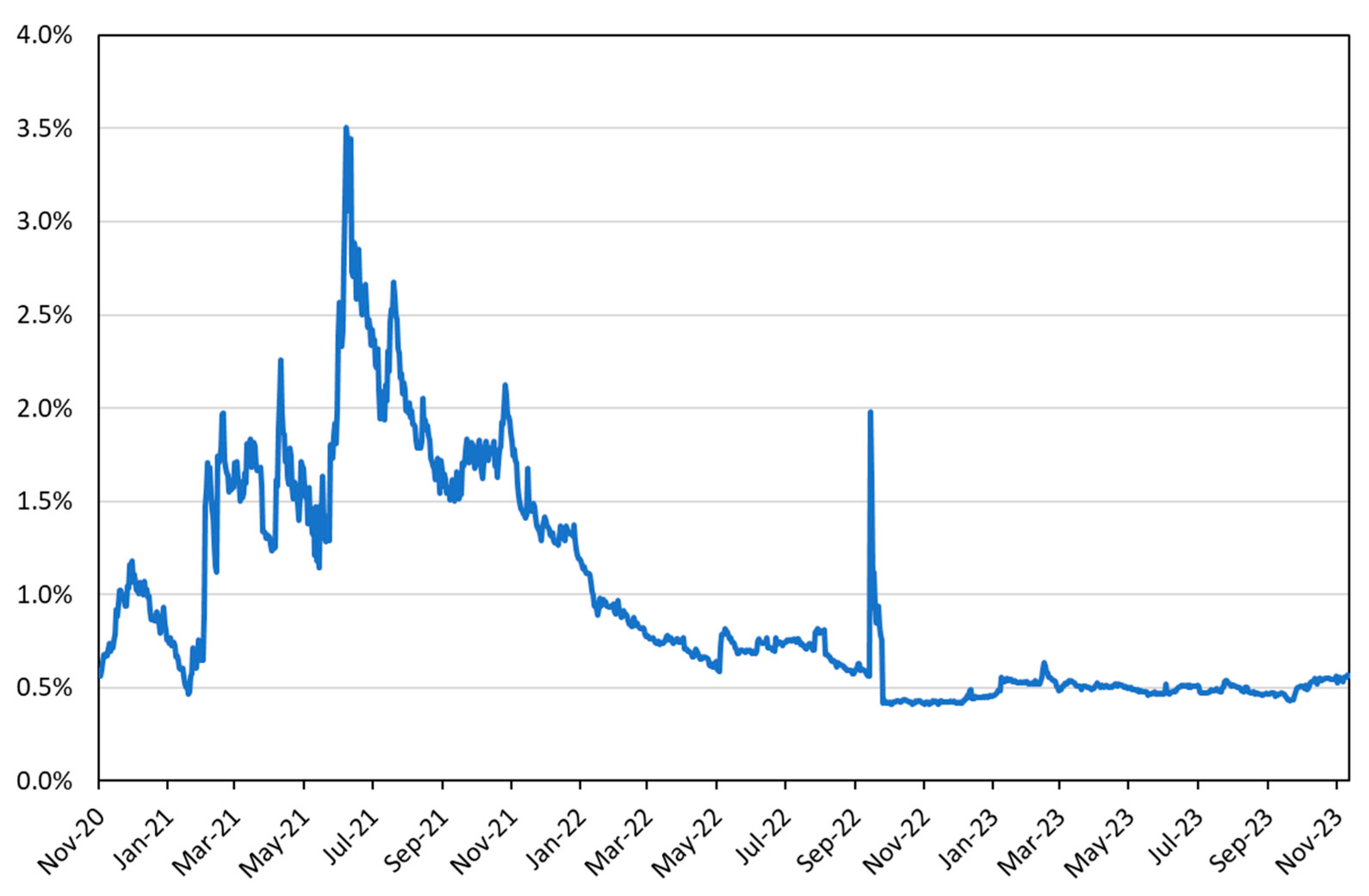

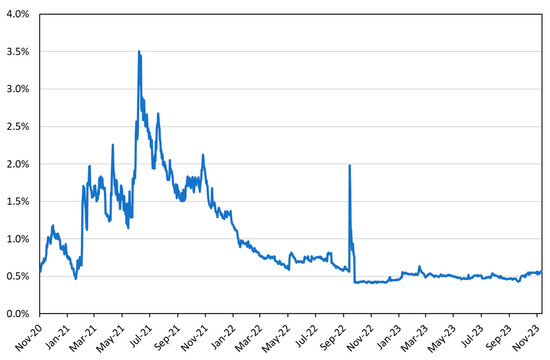

Despite the fact that payments using crypto-assets can take place on most blockchains, coders have developed DeFi payment protocols specifically focused on payment functionalities like streaming, micro-payments, and faster processing, in an attempt to facilitate payments using crypto-assets. A DeFi payment protocol is essentially a set of rules and procedures implemented as a smart contract on top of a blockchain (usually Ethereum), that allows for peer-to-peer payments. These payments are recorded on the underlying blockchain. According to DefiLlama [36], DeFi payment protocols represented 0.5% of the total value locked (TVL) in DeFi at the end of November 2023. This equates to approximately USD 264 million (Figure 1). This could mean that only around 0.5% of all the value locked in crypto-assets is used for making payments.

Figure 1.

TVL of protocols for payments as % of total TVL in DeFi (Source: our calculation on DeFiLlama).

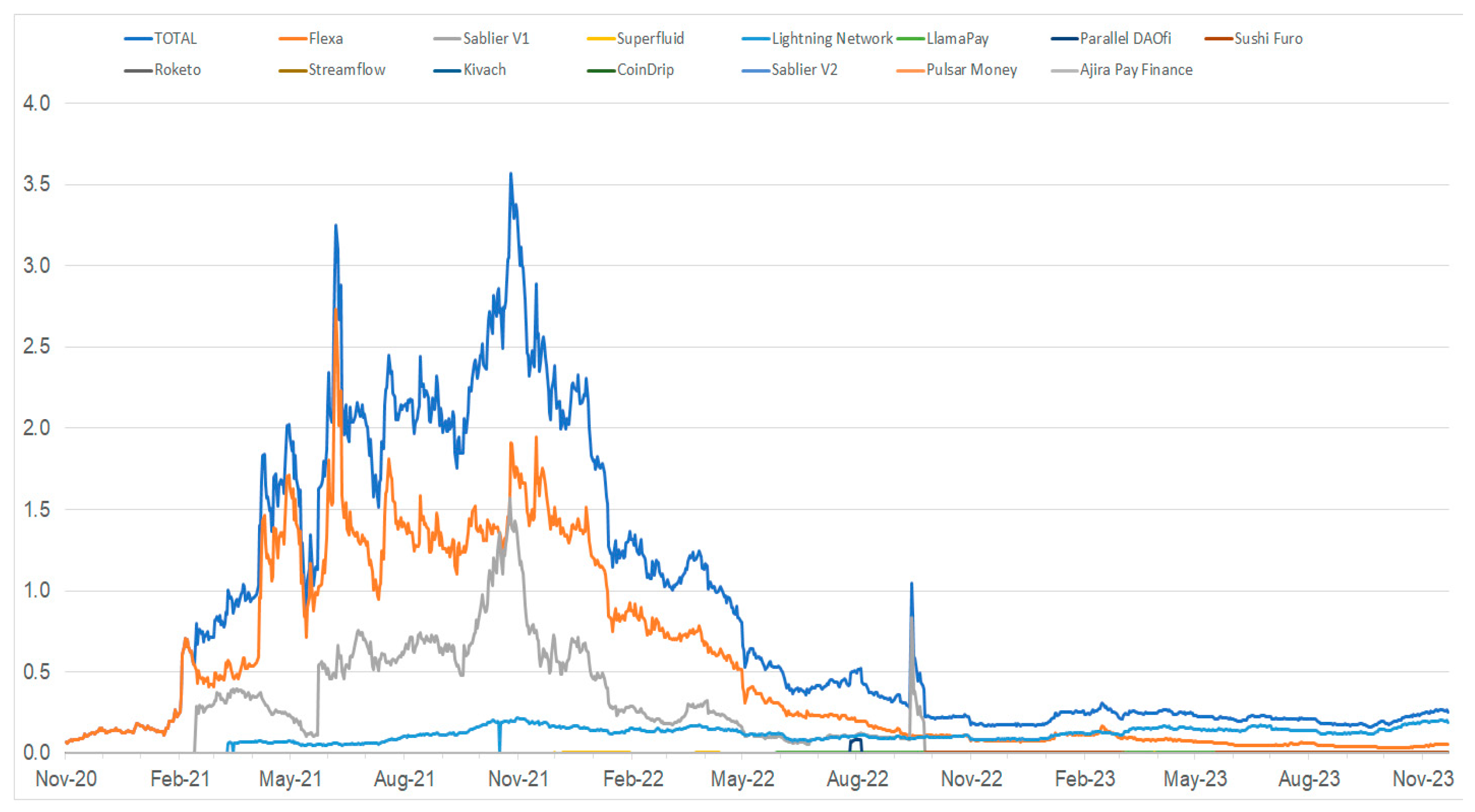

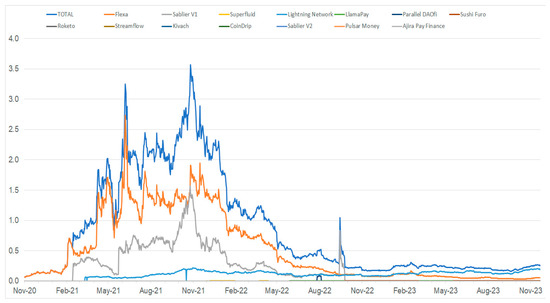

The TVL for payments reached a peak towards the end of 2021 and then declined. It remained quite steady for almost a year (end of 2022–end of 2023), at less than 10% of the November 2021 historical maximum (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

TVL for payments per protocol (in USD billions) (Source: our calculation on DeFiLlama).

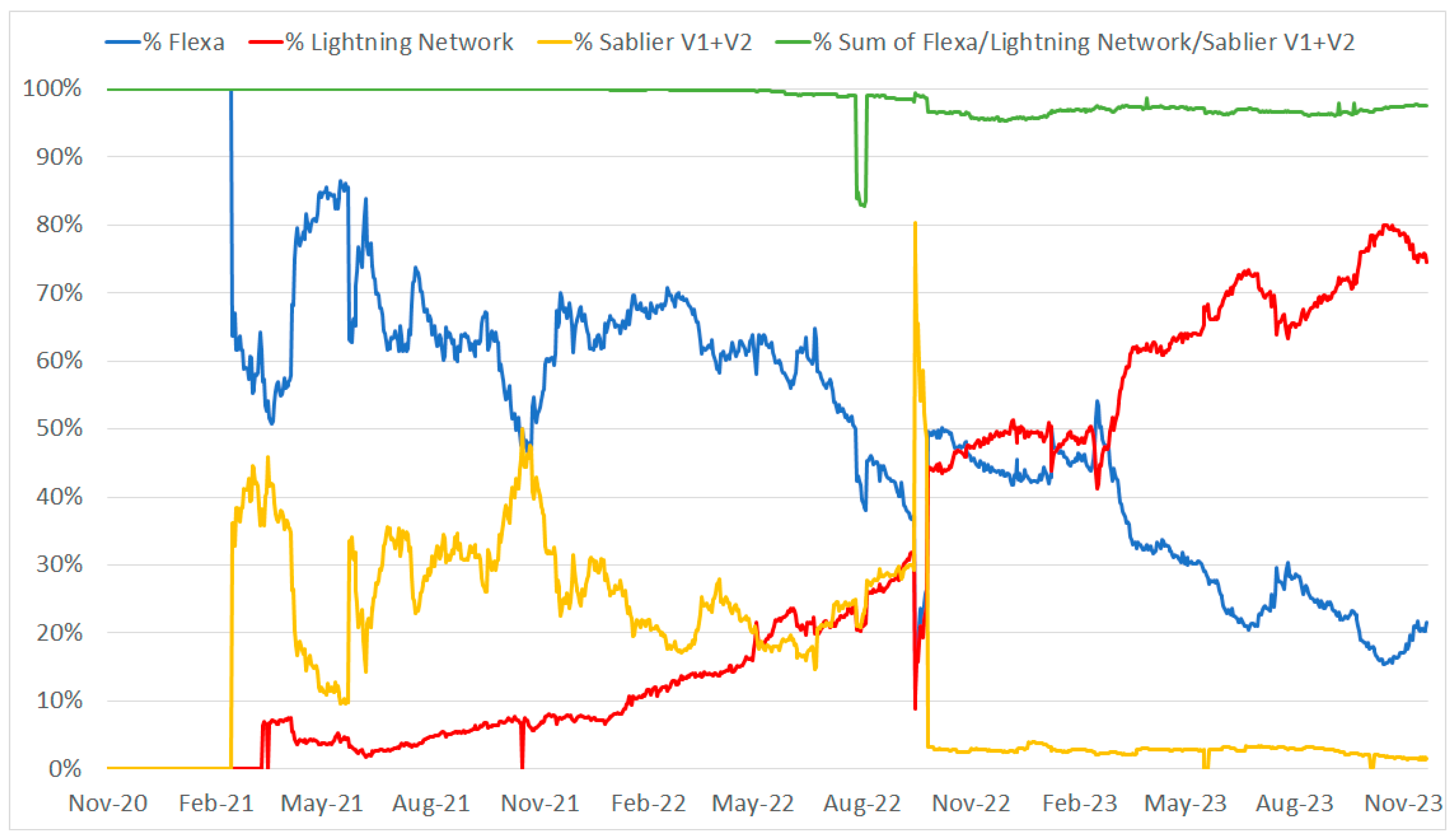

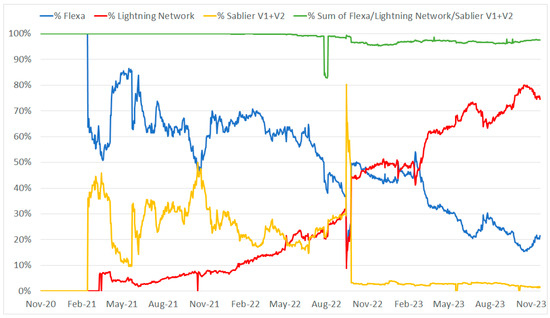

The market for DeFi payment protocols is highly concentrated: four protocols (Flexa [20], Lighting Network [16], Sablier [17], and LlamaPay [18]) represent almost 100% of the TVL (Figure 3), with the first three accounting for the largest share. Two protocols, in particular, dominated at the end of 2023, the Lightning Network and Flexa, with shares of 74.53% and 21.52%, respectively, on 30 November 2023 (see Appendix C).

Figure 3.

TVL of top protocols for payments as a % of all protocols for payments (Source: our calculation on DeFiLlama).

3.3. Crypto-Asset Payment Gateways

Crypto-asset payment gateways are new service providers that facilitate transactions between merchants and customers by processing payments in crypto-assets. They bridge the traditional financial systems and crypto-assets by enabling e-commerce platforms, physical merchants, and other market participants to include crypto-asset payments among their payment options. They offer functionalities, such as accepting and processing crypto-asset payments, real-time transaction confirmation, automatic conversion to fiat currency, wallets for storing crypto-assets, and the encryption of transaction information by utilising blockchain technology. Crypto-asset payment gateways integrate with e-commerce platforms point-of-sale systems, in particular, shopping cart software, and billing systems. They charge fees and provide dashboards to help track transactions. While these systems most commonly support bitcoin payments, some gateways also support alternative crypto-assets, such as ether, litecoin, and bitcoin cash. Some examples of crypto-asset payment gateways [37] are Coinbase Commerce [38], CoinGate [39], CoinRemitter [40], CoinsPaid [41], and Coinify [42]. Through a crypto-asset gateway, a crypto-asset payment made by a customer is credited to a merchant, from where it can be transferred to another wallet. For example, a Coinbase Commerce account is a digital account that allows merchants to accept payment in one of seven crypto-assets. Anyone can sign up for these gateways using a valid email address and a phone number, no matter where the customer is. It also requires the integration of two-factor authentication. A retail user can pay a merchant using a hot wallet. A hot wallet is a crypto-asset wallet that is always connected to the internet and crypto-asset network. This wallet shares a public key with a merchant, which the merchant then uses to access (debit) their customer’s funds on the blockchain, while crediting their own account. Coinbase Commerce targets online service providers, such as Shopify [43] and Woo Commerce [44], and also freelancers and small business owners [45]. Businesses incur costs for (i) transactions due to the need to pay the miners of the crypto-asset network and (ii) for converting crypto-assets to fiat money, which can be performed using a crypto-assets exchange.

4. Payees—Geographical Area and Market Sector

4.1. Geographical Area

At the global level, the United States recorded the highest number (28,143) of cATMs in 2023, according to CoinATM radar [46], with more machines found there than elsewhere in the world. Canada (2803) and Australia (760) followed in second and third place. The UK, which was ranked 17th in 2022, fell to 61st place in 2023. This was probably due to the fact that the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has actively been pursuing crypto ventures in the UK. The FCA has been raising concerns about crypto-assets, in part due to the spike in interest in the crypto market that occurred in 2021, and because crypto-assets remain an unregulated product in the UK [47].

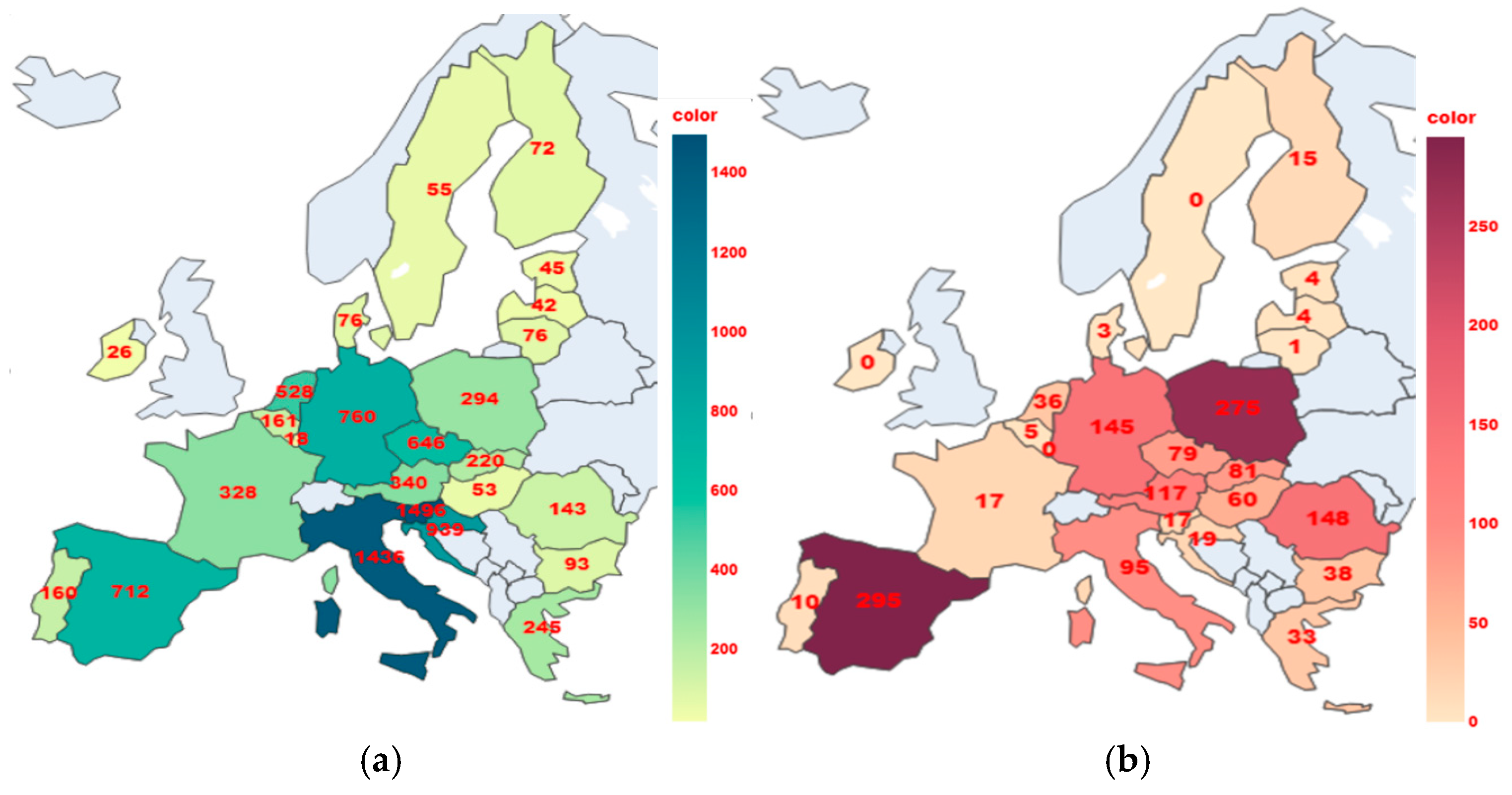

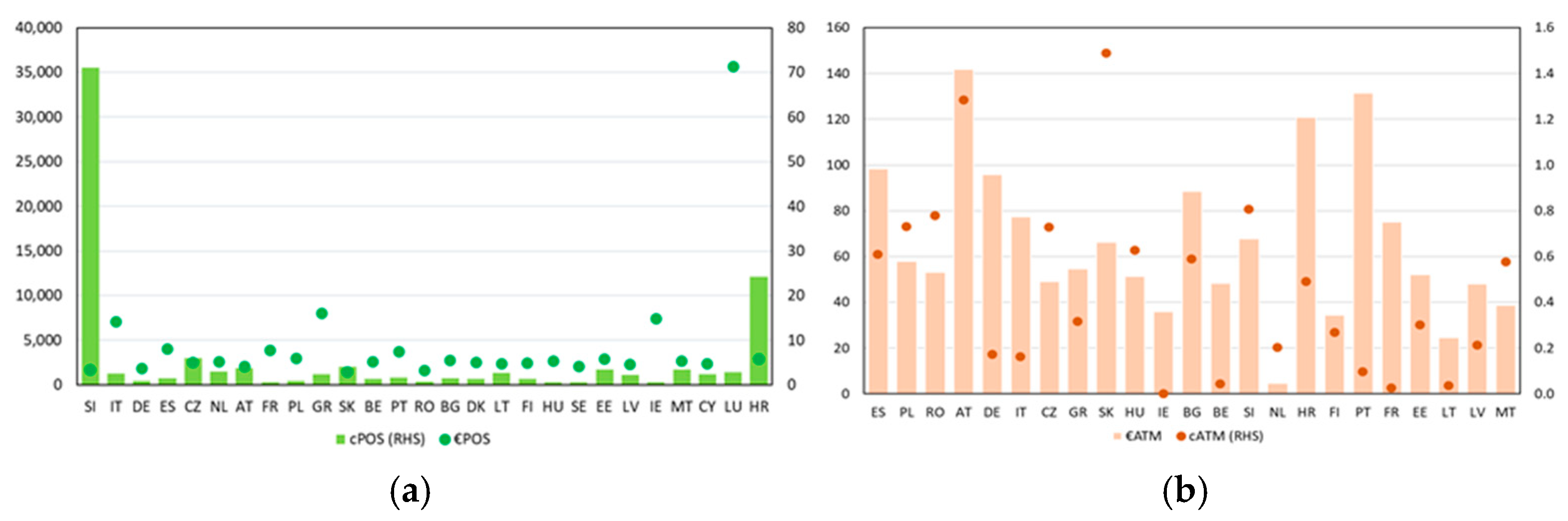

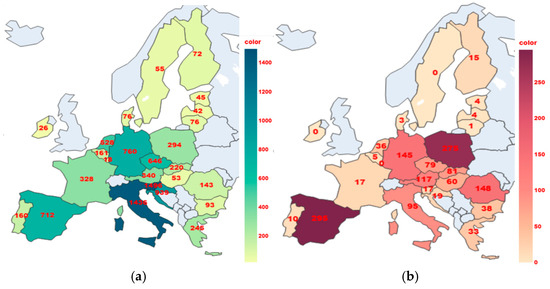

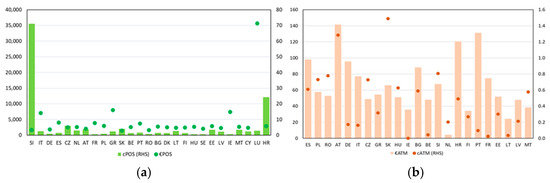

At the European Union level, cPOSs and cATMs are unevenly distributed. This may reflect the use of crypto-assets throughout the EU and the collective willingness to explore and integrate blockchain solutions into traditional financial frameworks with different degrees of adoption. In 2023, there were more than 1400 cPOSs in Slovenia and Italy, marking a strong presence in southern Europe (Figure 4a). There were over 500 terminals in Germany, Spain, and Hungary, while Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, and Ireland counted less than 100 terminals. In the EU, cATMs seem to be less common than cPOSs, reaching almost 300 terminals only in Poland and Spain (Figure 4b). An analysis of Coinmap [48] and CoinATM radar [46] shows a growth rate of about 60% in the EU between 2018 and 2023 for both cPOSs and cATMs, possibly signalling growing interest in the use of these instruments.

Figure 4.

(a) Distribution of cPOSs in the EU in 2023. (b) Distribution of cATMs in the EU in 2023. (Source: Coinmap and CoinATMRadar).

Nevertheless, the share of cPOSs and cATMs relative to the countries’ populations remains very limited compared to the number of POSs and ATMs in fiat currency (2 versus 3573 and 0.6 versus 73—Figure 5a,b).

Figure 5.

(a) Countries’ share by type of POS. (b) Countries’ share by type of ATM (by 100,000 population). Data are calculated as follows: bars = number of € POS (or € ATM)/100,000 population; points = cPOS (or cATM)/100,000 population. Source: national statistics for population; ECB for € POS and € ATM; Coinmap and CoinATMRadar for cPOS and cATM.

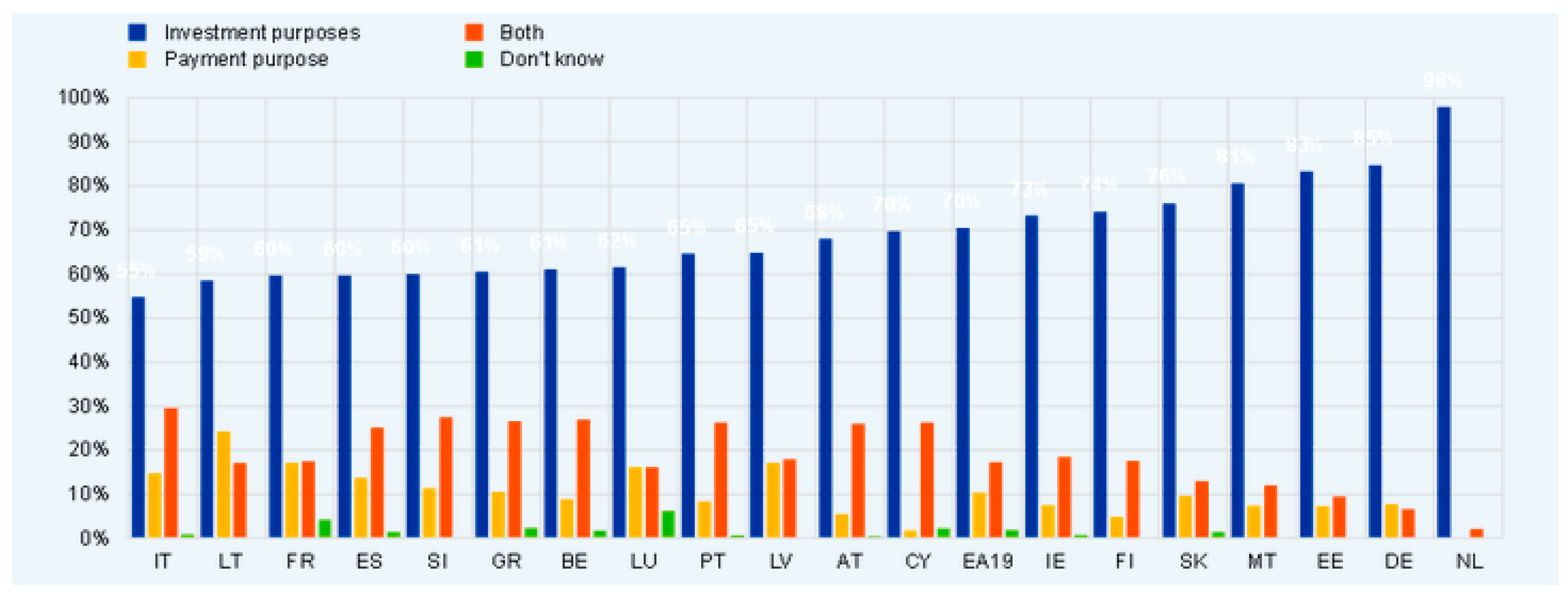

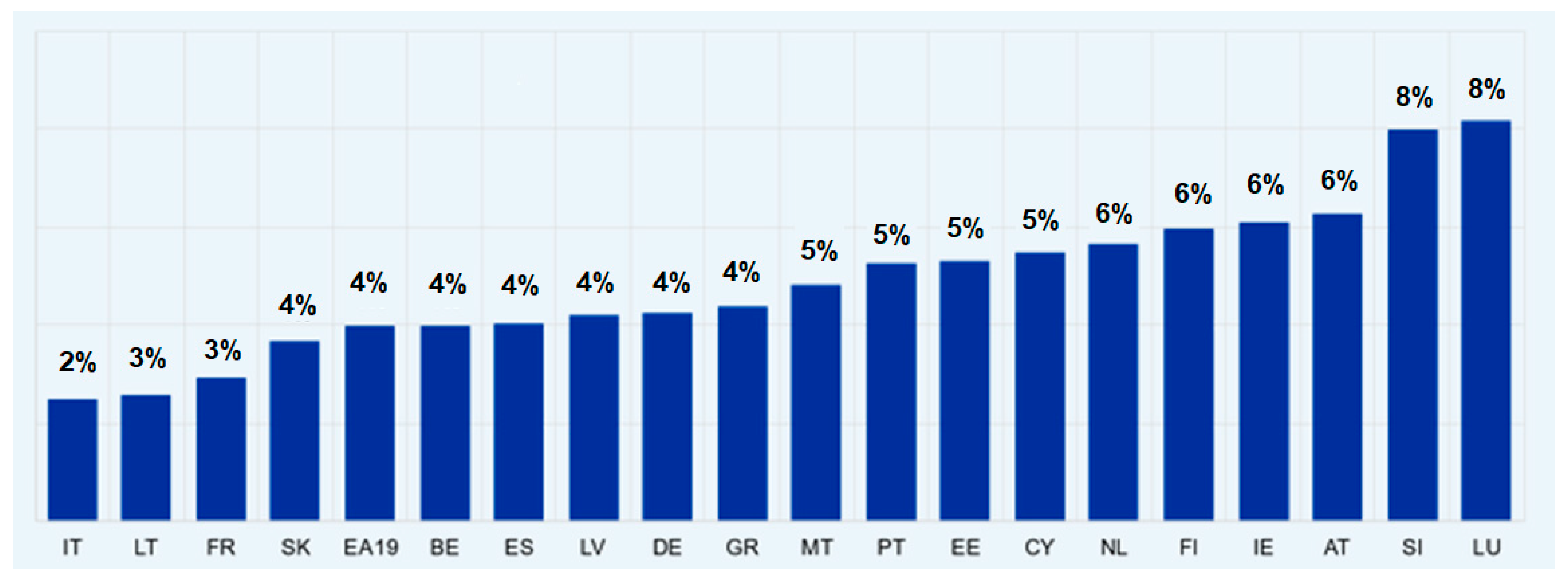

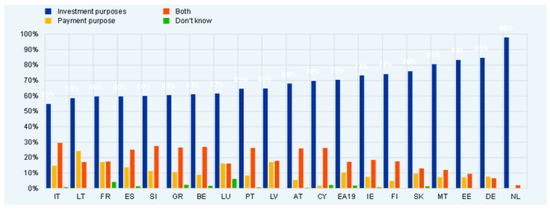

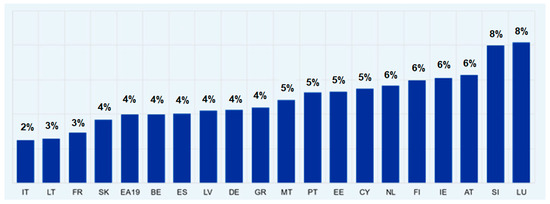

According to the Study on the Payment Attitudes of Consumers in the Euro area [49], in all the participating countries, crypto-assets are primarily used for investment purposes. Lithuania, France, Latvia, Italy, Luxembourg, and Spain stand out as the countries with the highest percentage use of crypto-assets for payments (Figure 6). Beyond these variations, the differences between the countries do not lead to any other apparent conclusions. Overall, the use of crypto-assets for payments appears to be low.

Figure 6.

Use of crypto-assets. (Source: Study on the Payment Attitudes of Consumers in the Euro area (SPACE)—2022 [49]).

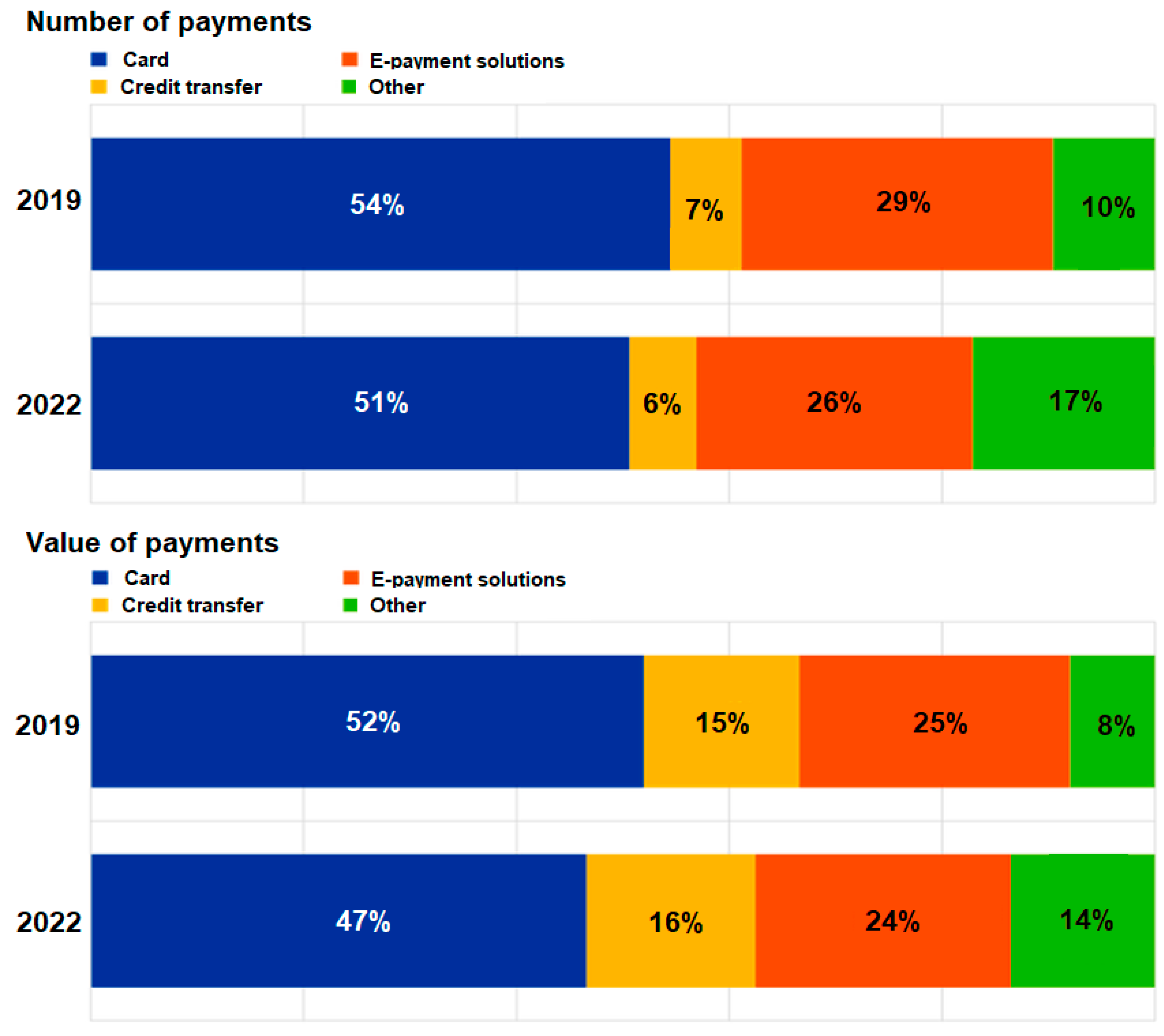

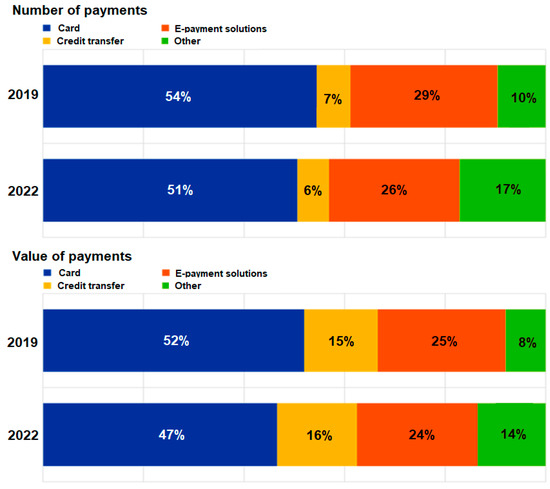

Figure 7 illustrates the breakdown of the number and value of online payments by payment instrument in the euro area. The four categories include payments by (i) card, (ii) credit transfer, (iii) e-payment solutions (encompassing PayPal and other online or mobile methods, such as Klarna [26], iDeal [25], and Afterpay [50]), and (iv) other (encompassing loyalty points, vouchers, gift cards, crypto-assets, and other payment instruments). The first three categories show a slight decrease between 2019 and 2022, except for a marginal increase in the value of credit transfers. In contrast, both the number and value of payments in the fourth category, including crypto-assets, show a significant increase.

Figure 7.

Breakdown of number and value of online payments by payment instrument in the euro area, 2019–2022. (Source: Study on the Payment Attitudes of Consumers in the Euro area (SPACE)—2022 [49]).

4.2. Market Sector

Those payees around the world that accept crypto-assets for payments belong to a diverse range; they are not restricted to a particular segment of the market. Bitcoin can be spent in shops around the globe and, according to bitcoin maps, more than 10,500 merchants accept payment in bitcoin [51]. Other sources support the fact that a growing number of companies accept payments in crypto-assets [52]. An attempt to categorise the wide variety and number of payees accepting crypto-assets results in a broad and varied list, including online market places, such as Crypto Emporium [53] and BitDials [54]; gift card shops, such as Bitrefill [55]; Microsoft; charity organisations, such as the American Red Cross; luxury fashion shops, such as Ralph Lauren; and e-commerce sites for managing inventory, shipping, and plane tickets.

Many of these merchants are stores that use the crypto-asset payment service provider and crypto-asset payment processor BitPay [33], which is based in the USA, and owns a European subsidiary based in the Netherlands. These merchants receive fiat money rather than bitcoins, and other crypto-assets paid as bitcoins to merchants are automatically exchanged for fiat money before they are transferred to merchants. On 22 February 2024, BitPay [33,56] claimed to have processed 334,486 crypto-asset transactions (assumed to be payment transactions) over the last six months.

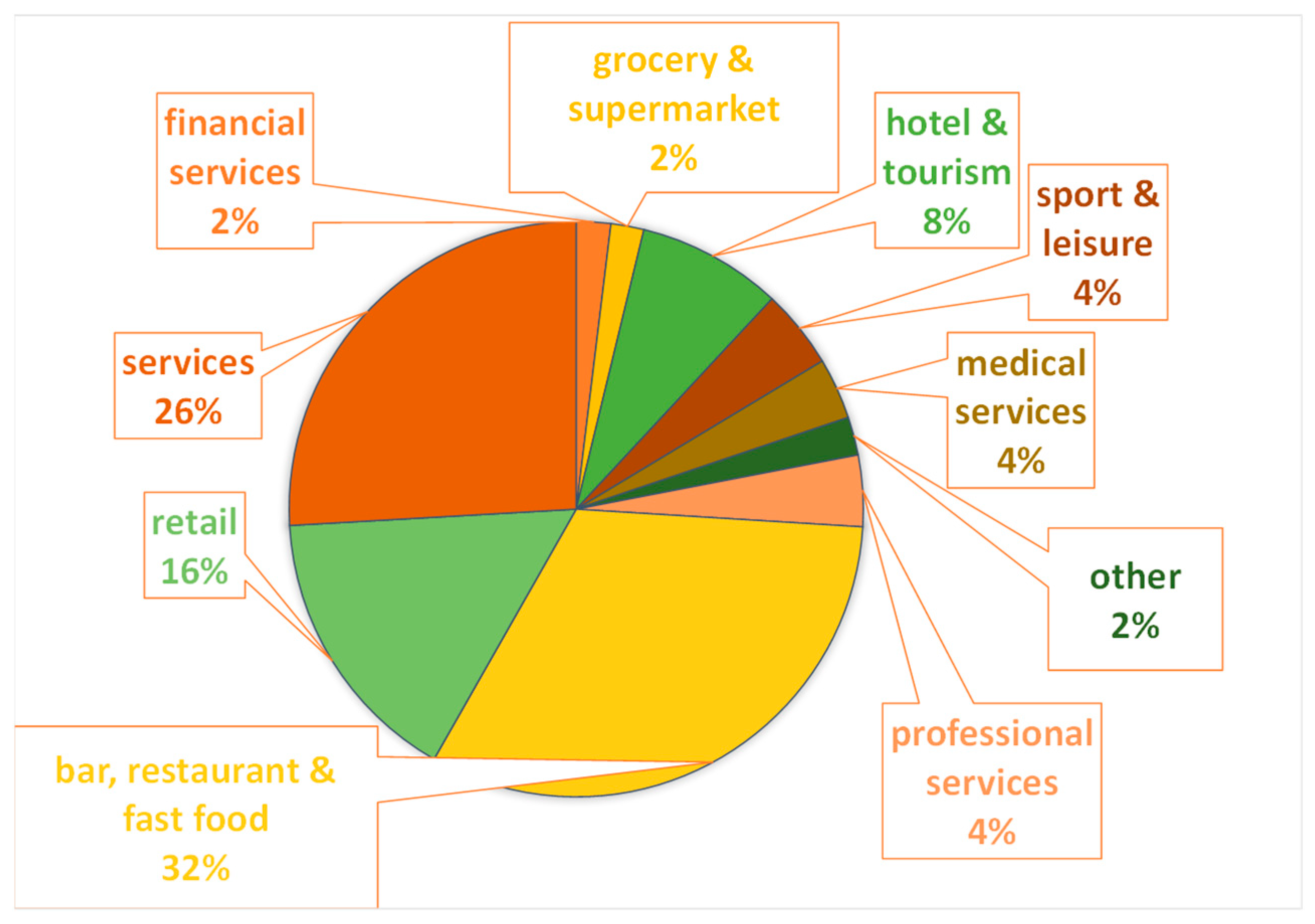

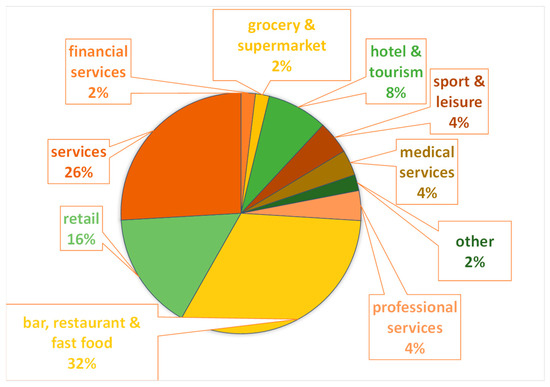

In Europe, the merchant category distribution of bitcoin cPOS terminals shows that more than 50% of these terminals are placed in catering and service stores (Figure 8). There are no data available on the actual use of bitcoin for making payments to merchants, either in terms of the value or volume of transactions. Furthermore, these figures must be considered with caution, as they were collected by Coinmap, CoinATM radar, and BTCmap on a voluntary basis, and include some repetitions and incomplete information on locations and merchant categories (see Appendix A for the dataset specification), which probably could not be completely eliminated, despite cleaning.

Figure 8.

The 2023 cPOS market sector as a share of the total volume (Source: BTCmap).

5. Payers—Who Uses Crypto-Assets for Payments?

The ECB SPACE report for 2022 [49] mentions that the influence of crypto-assets on the payment landscape was not considered in the SPACE report of 2019. However, since then crypto-assets have spread, perhaps due to secondary effects caused by pandemic restrictions. In Europe, this may have been further supported by increased regulatory clarity, which could have affected consumers’ perceptions of crypto-asset usage and payments. The monitoring of crypto-asset-related developments is therefore becoming more and more relevant.

There is no publicly available information about who actually uses crypto-assets for payments. However, data on ownership and use cases within the euro area are available [57]. Figure 9 shows the overall ownership by country, with the respondents indicating whether they hold crypto-assets (independent of the size of the holding in proportion to other assets the respondents may hold). The euro area average shows that a modest 4% of the population holds crypto-assets, with the highest percentage share being in Slovenia (8%) and Luxembourg (8%). In Slovenia, the highest percentage of crypto-assets is held by people in the 25–39 age group. Despite increased attention in popular culture and the financial markets, the uptake of crypto-assets by the population in general remains relatively low. Research conducted by the Dutch National Institute for Budget Information (Nibud) in November 2021 showed that 27% of young adults (18–30 years old) invested in (not paying with) crypto-assets [58]. Pos concluded in July 2022 that given the early stages of the discovery and establishment of the utility functions of crypto-assets in mainstream society (for example, as a means of payment or exchange), a negative relationship between its utility and the motivation to invest still exists today. In the future, when crypto-assets are regarded a more established means of payment, for example, this relationship may turn positive [59].

Figure 9.

Ownership of crypto-assets (Sources: Study on the Payment Attitudes of Consumers in the Euro area (SPACE)—2022 [49]).

The individuals who disclosed that they held crypto-assets were asked about their use of them, either for payments, investments, or both. The results varied widely across groups, with a strong emphasis on saving for investment. In most countries, two to three times more individuals owned crypto-assets exclusively for investment compared to those holding them solely for payment purposes.

Examining the countries where investment predominated, the survey revealed that around 18% of French consumers used crypto-assets for payments, while 60% considered them an investment vehicle; in Germany, 85% held crypto-assets for investment purposes, 8% for making payments, and 7% for both. Conversely, 24% of the users of crypto-assets in Lithuania reported using them for payments, and 17% also used them for investments. While crypto-asset activities, including stablecoin payments, were observed across all eurozone countries, the reported use for payment purposes was trivial or niche by the end of 2023.

6. Existing Commercial Payment Systems That Incorporate Crypto-Assets for Payment Services—Interoperability

6.1. PayPal

PayPal [60] offers customers the ability to buy, sell, hold, send, and receive a range of crypto-assets, including bitcoin, ethereum, bitcoin cash, and litecoin. Customers can also use the proceeds from crypto-assets sales to pay for purchases at checkout. PayPal provides the option for customers to convert their crypto-asset holdings into fiat currency at a given exchange rate, which, according to PayPal’s terms and conditions, is defined by PayPal. The platform utilises a single third-party custodian to hold customers’ crypto-assets in PayPal’s name in a custodial account. PayPal acknowledges the concentration risk associated with this setup, as stated in the annual report submitted to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission for the fiscal year ending 31 December 2022.

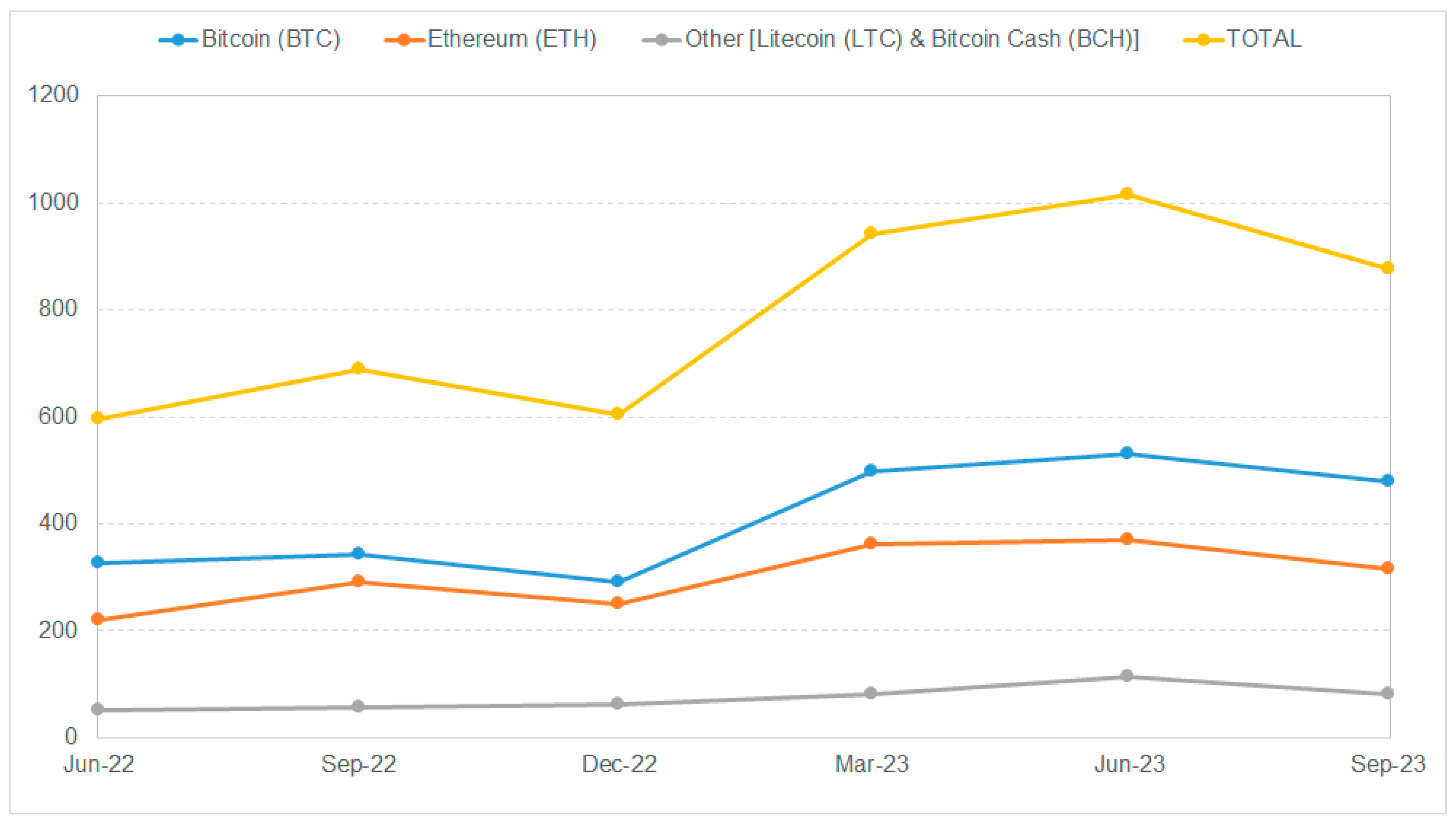

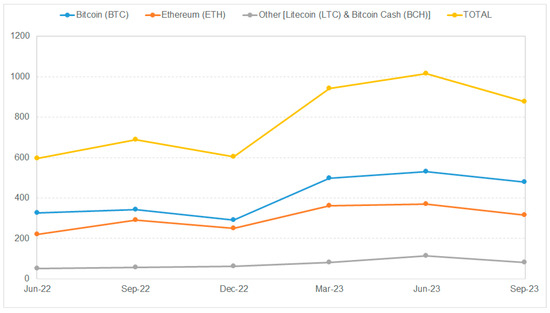

The PayPal crypto-asset service was initially introduced in the USA in October 2020, followed by its launch in the UK in August 2021. However, in October 2023, the purchasing of crypto-assets in the UK was temporarily paused until early 2024, to comply with additional UK regulation requirements. However, customers were still allowed to retain or sell previously acquired crypto-assets. Finally, the PayPal crypto-asset service became available in Luxemburg in December 2022. Table 1 and Figure 10 summarise the value of the crypto-assets held by PayPal customers in the USA (for raw data, please refer to Appendix B).

Table 1.

PayPal custody of crypto-assets (in USD MLN).

Figure 10.

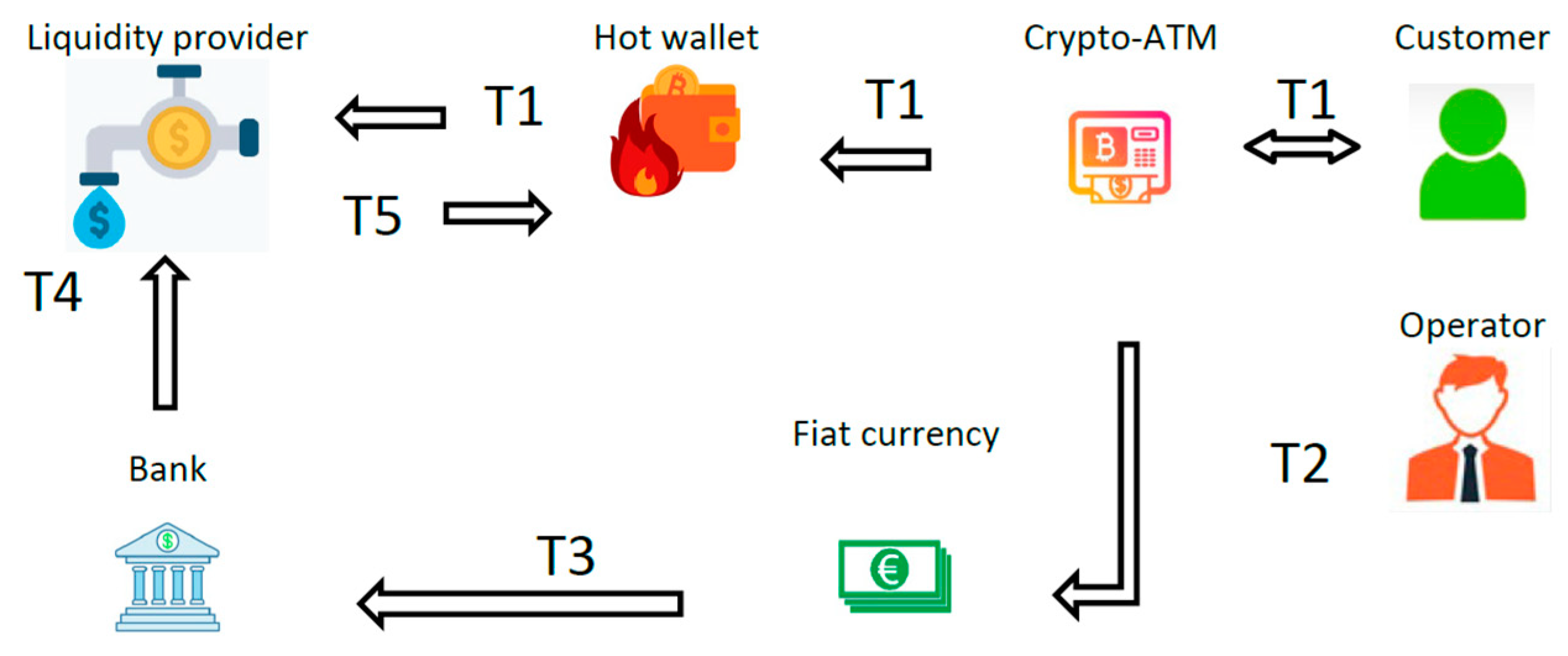

PayPal custody of crypto-assets (in USD MLN) (Source: PayPal annual/quarterly reports to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission [61]).

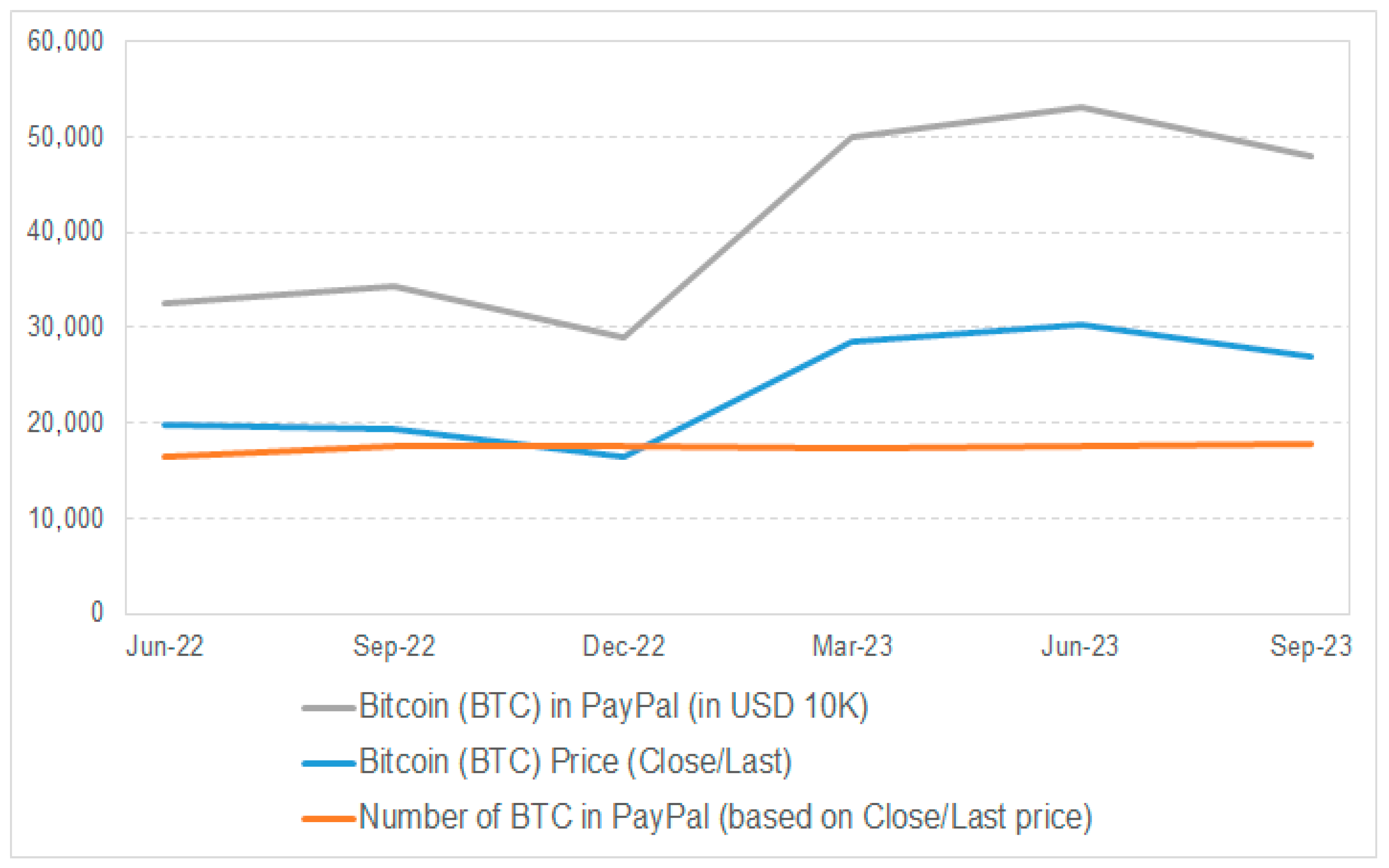

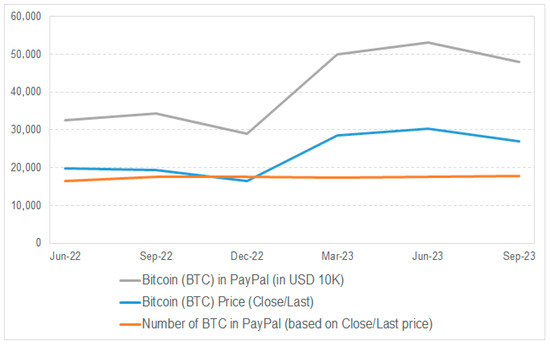

Using the daily prices of the crypto-assets, it is possible to calculate the absolute number of crypto-assets that are in the custody of PayPal (Table 2 and Figure 11, specifically for bitcoin).

Table 2.

PayPal custody of bitcoin.

Figure 11.

PayPal custody of bitcoin (BTC) (Source: PayPal annual/quarterly reports to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission [61]).

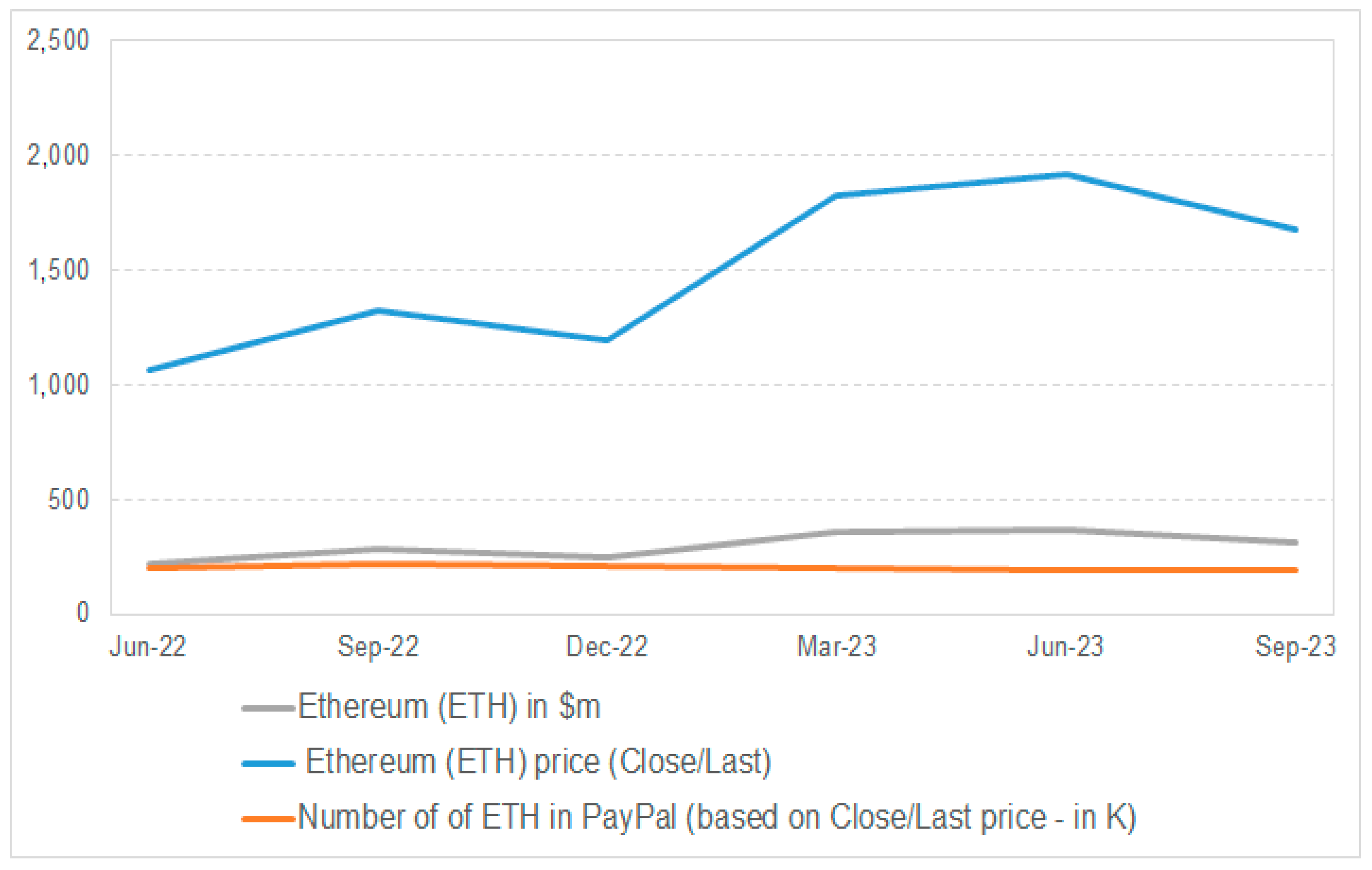

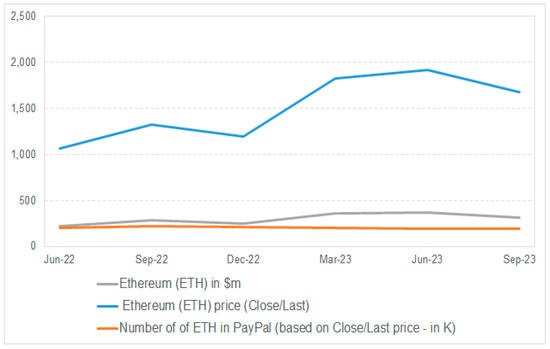

The value (in USD) of the bitcoins safeguarded for PayPal customers is closely aligned to the fluctuations in the bitcoin price. This results in an almost constant absolute number of bitcoins throughout the period covered by the reports. This lack of variation in the number of crypto-assets may evidence a lack of their use in/for payments and may prove that customers see crypto-assets as investments rather than as a means of payment. A similar, though milder trend, is observed for ethereum (Table 3 and Figure 12).

Table 3.

PayPal custody of ethereum.

Figure 12.

PayPal custody of Ethereum (ETH) (Source: PayPal annual/quarterly reports to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission [61]).

Litecoin and bitcoin cash are presented in aggregate in the reports. It is therefore not possible to extract the absolute numbers by their respective price. All the amounts/values previously presented refer to the custody of the crypto-assets owned by PayPal customers. It is not clarified within the reports which amounts/values were used for payments. However, since PayPal is an online payment solution, at least a fraction of the crypto-assets purchases may have been intended for prospective payments (when potentially their value could have risen more), and not solely for investment. The relatively flat curve for the number of crypto-assets, especially of bitcoin, over a 15-month period is worth examining in further detail. A potential explanation could be that the initial purchases of crypto-assets were not followed by sales or they were not used for payments. Alternatively, the initial purchases of crypto-assets were used for sales and/or payments, but the recipients of the crypto-assets were also in PayPal, so the total value was not affected. In August 2023, PayPal launched its own stablecoin, namely PayPal USD (PYUSD). According to PayPal, the PayPal USD stablecoin is fully backed by US dollar deposits, short-term US treasuries, and similar cash equivalents, and can be redeemed for US dollars at a ratio of 1:1 [62]. Initially, it was made available to eligible US PayPal customers and could be used for payments. In March 2024, PayPal announced that the users of its overseas money transfer app Xoom [63] would pay no fees if they used PYUSD to fund their transfers, in an effort to favour its use for international remittances.

6.2. Google Pay and Apple Pay

Google Pay [64] and Apple Pay [65] are mobile payment services offered by Google and Apple, respectively, that allow users to make payments, both online and in person. Both Google Pay and Apple Pay encapsulate the underlying payment method [66], e.g., debit or credit card, by sending a virtual account number to the payee and not the actual card number. They are available in many countries around the globe, including all EU countries [67]. Google Pay and Apple Pay can be used to buy crypto-assets, either on compatible crypto exchanges, e.g., Coinbase [38,68] or Binance [30,69], or on crypto payment gateways, e.g., BitPay [33,56]. Moreover, payments can be made with crypto-assets by the following:

- Linking to a crypto debit/credit card, e.g., Coinbase card (VISA debit card) [70], BitPay card [71], Venmo credit card (VISA credit card) [72], or Bakkt card (VISA debit card) [73]. When such payments are processed, the crypto-assets spent are converted to fiat money.

- Using a payment gateway. A user makes a payment by connecting a Coinbase Commerce account to a bitcoin wallet, and then choosing bitcoin and Google Pay at the online checkout of a merchant that accepts bitcoin payments through Coinbase Commerce. Google Pay then sends the payment to Coinbase Commerce, which processes the bitcoin transaction and credit the merchant’s account.

Crypto cards are available worldwide with different terms. For example, a Coinbase card is available in the EU [74], but does not support all the features that are available in the US, such as the cashback feature, while the BitPay card is currently available to US residents only. Since early 2023, Google has allowed users to pay for cloud services with crypto-assets [75]. This fact may be an indication of a potentially wider future inclusion of crypto-assets in Google Pay. Apple offers the Tap to Pay feature in the iPhone, which allows merchants to receive contactless payments from credit or debit cards, Apple Pay, and Apple Watch [76]. This requires only an iPhone on the merchant’s side and no additional terminals or hardware. Since Apple Pay supports crypto cards, as mentioned above, this means that customers can make physical contactless payments to merchants using crypto-assets. It should be noted that the Tap to Pay feature is currently available in selected countries only, including the USA, the UK, and only in France and Netherlands in the EU.

The relevant statistics indicate a considerable level of Google Pay and Apple Pay adoption at a global level (Table 4). It should be noted that, although they are relevant for illustrating the level of adoption, these numbers do not illustrate actual payments made with crypto-assets at this point in time.

Table 4.

Use of Google Pay and Apple Pay for online payments or at POS.

7. Concluding Remarks

In this paper, we explore the current use of crypto-assets for payments, taking into account mostly unbacked crypto-assets, while only referring to crypto-assets that are stablecoins where specifically mentioned, trying to answer the related questions that form the topic of crypto-asset-based (retail) payments: (a) which crypto-assets are used for (retail) payments, (b) why and how are crypto-assets used for (retail) payments, (c) where are crypto-assets used for (retail) payments, and (d) who uses crypto-assets for (retail) payments.

Our analysis thus provides rich evidence on various dimensions and indicates that the market for crypto-assets is volatile and fragmented, and that crypto-assets are mostly used for speculative purposes rather than for payments. Specifically, although crypto-assets, such as bitcoin, were originally intended to be used for payments in general, their price volatility seems to have prevented them from being broadly used for this purpose in practice. Indeed, this analysis shows a particularly low (and in specific cases stable) use in practice of these unbacked crypto-assets via the various available methods, i.e., crypto-asset payment protocols and gateways. Furthermore, this study of the literature shows that although crypto-assets can be used to pay in many shops and restaurants and to make peer-to-peer payments via multiple ways, the most prominent use cases for using crypto-assets as payments are the following: (i) micropayments, (ii) streaming, (iii) instant settlement for tokenised assets, and (iv) cross-border payments. We note that when used for payments, crypto-assets are oftentimes converted into fiat money. This means the actual payments are not made using crypto-assets. At the same time, our analysis regarding the payers shows that crypto-assets are predominantly held by younger age groups and this may hint at a potential broader adoption in the future.

Despite the current low volume of examined crypto-asset-based payments, this study of the ways to pay with crypto-assets and their adaption shows that the rise of DeFi protocols and collaborations between crypto exchanges and payment firms has expanded the usability of crypto-assets in everyday transactions. Moreover, the greater presence of cPOSs and cATMs in several countries may indicate that both merchants and customers are interested in offering and using crypto-assets for payments. However, the data for PayPal show an almost constant quantity of bitcoins and ethereum held by PayPal users throughout 2022 and 2023. This may evidence their lack of use for payments and may prove that users hold them for reasons other than as a means of payment or, alternatively, that the payees kept the crypto-assets in PayPal, so the total amount was not affected. The next steps in this line of research could be to analyse whether the use of crypto-assets for payments, for example using PayPal, is higher when the price of crypto-assets stabilises following a peak. This could indicate that users buy crypto-assets for speculative reasons and only use them for payments after they have realised a capital gain.

Due to the lack of official data regarding the use of crypto-assets, we have based our analysis on a combination of data from various publicly available sources and studying the developments and trends in this field. One such trend is the fact that some payment service providers are developing and integrating stablecoins into their services. The most relevant example is PayPal’s launch of its own dollar-pegged stablecoin (PayPal USD). Given that PayPal operates akin to a big tech entity, in that it is deeply integrated into online commerce, with an extensive global customer base and expansive operations, it could easily and quickly scale up the use of its stablecoin.

We thus note that the current developments towards interoperability and integration with existing financial infrastructures, in combination with the entering into force of the MiCAR and other international regulatory developments, such as the current ones in the US, could potentially increase the interest in owning and using crypto-assets that qualify as stablecoins. Looking ahead, factors, such as regulatory approval, technological advancements, and expanding use cases, could drive the adoption of crypto-assets for payments. However, this would require overcoming a number of challenges, such as high volatility and lack of legal settlement finality. While payment protocols aim to address these issues, a broader adoption of crypto-assets also depends on regulatory factors.

We believe that fostering a clear understanding of the developments around crypto-asset payments and monitoring the various degrees of adoption throughout different markets could contribute to identifying the broader implications of using crypto-assets in the payment ecosystem and in maintaining the integrity and stability of the financial system. Our work aims to provide a basis for understanding the domain via various dimensions that need to keep being explored by the interested authorities and other stakeholders, keeping in mind that to achieve a thorough and comprehensive analysis of the domain, it would be useful to improve the quality of the data collected and to enhance data sharing protocols, as well as to establish monitoring capabilities that are in line with the MiCAR requirements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.K. and P.M.; Methodology, E.K. and P.M.; Validation, E.K. and P.M.; Investigation, E.K. and P.M.; Writing—original draft, E.K. and P.M.; Writing—review & editing, E.K. and P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The work presented in this paper is part of the work conducted by the Crypto-Assets Monitoring Expert Group (CAMEG) of the Eurosystem Innov8 Forum (2024). We would like to thank the members of the group—Ellen Naudts, Laura Painelli, Anton Gehem, Antonio Perrella, and Beranger Butruille—for their valuable contributions and help with this work. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank of Greece or the European Central Bank.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. How cPOSs and cATMs Work

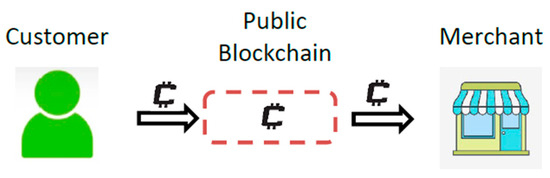

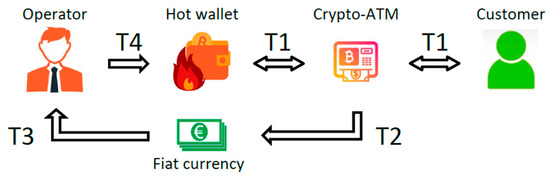

A transaction can be made at the physical point of sale (POS) [78] with crypto-assets in two ways: (i) through an exchange between two crypto wallets (wallet to wallet), where the transaction is validated by a blockchain (Figure A1); and (ii) via a three-party scheme. In both cases, the merchant enters the sum due in fiat currency on its device or on a dedicated physical cPOS device, and selects the crypto-asset with which the customer prefers to pay and/or is accepted by the merchant. A QR code or a public key is then generated through which the customer, using his/her device, can pay the sum due from his/her crypto wallet. In the case of a three-party scheme, an intermediary acts as the guarantor of the transaction on behalf of the merchant. The merchant can request the accreditation of the crypto-asset just used for the payment or the equivalent in fiat currency through their account.

Figure A1.

Crypto POS transaction.

Figure A1.

Crypto POS transaction.

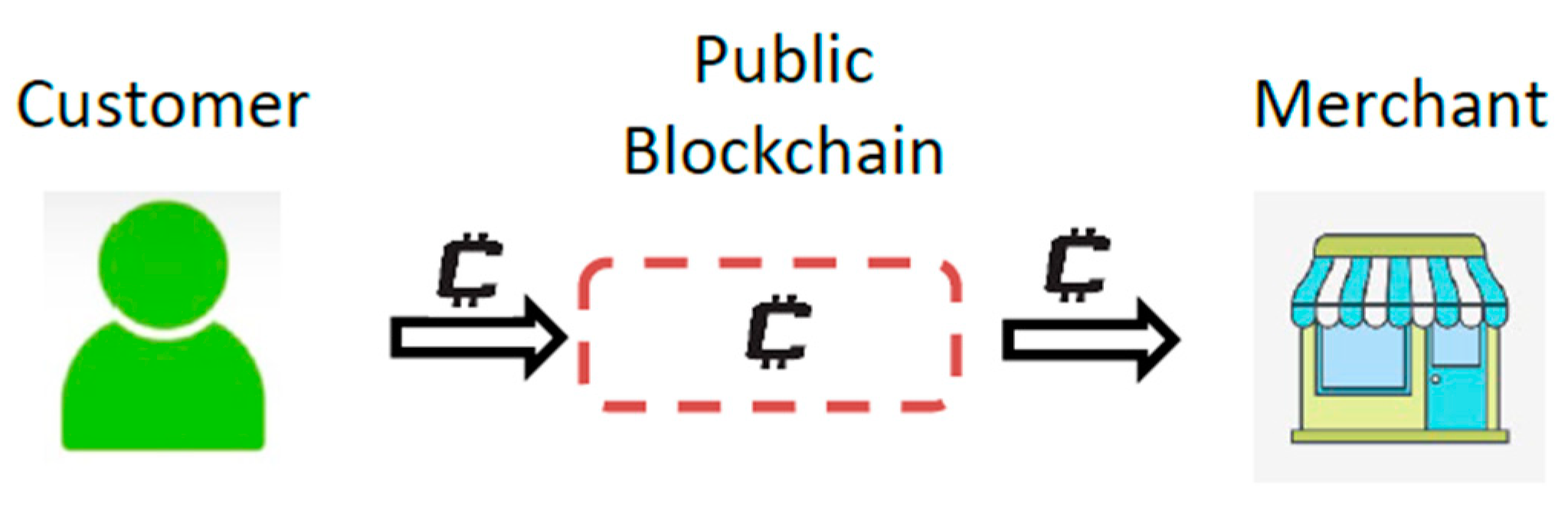

The process shown in Figure A2 represents the three-party scheme, where a payer can obtain goods or services by transferring crypto-assets. An exchange accepts the crypto-assets and transfers them to the merchant with which it has an agreement. The exchange regulates the transaction with the customer on a blockchain and orders a credit transfer in fiat currency for the merchant through a financial intermediary (a so-called hands-off circuit in which the merchant never comes into possession of the crypto-assets). Alternatively, the exchange can send the crypto-assets to the merchant’s account (hands-on circuit).

Figure A2.

Crypto POS transaction with an exchange.

Figure A2.

Crypto POS transaction with an exchange.

A cATM allows a user to make transactions in crypto-assets using cash, payment cards, or apps linked to traditional bank accounts. A user must register at the cATM, inserting a front/back photo of an identification document and providing a mobile number. Once the user has been verified, he/she will be able to access the service by entering his/her mobile number and typing or scanning the address of the wallet on which he/she wishes to receive the purchased crypto-assets. Finally, the user will insert cash or make a credit card payment in the fiat currency equivalent of his/her purchase of crypto-assets. The receipt issued by the terminal to confirm the purchase includes a QR code. This code contains the public and private keys and can be scanned and immediately recognised by digital wallet apps.

Two-way cATMs offer bidirectional functionality for both the purchase and sale of crypto-assets (e.g., Genesis Coin, General Bytes, and Lamassu), while one-way cATMs offer only the possibility of purchasing crypto-assets using fiat currencies (e.g., BitAccess). In the case of Bitcoin Teller, the transaction does not take place through a terminal but at a cash register, where the customer shows the QR code to a person to finalise the transaction.

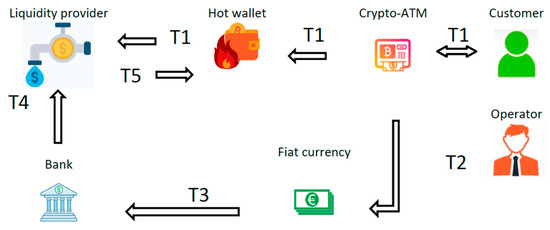

The operators who manage cATMs provide liquidity to a terminal using a crypto wallet that is constantly connected to the internet (hot wallet). Liquidity is provided to a hot wallet from a customer’s own capital (fiat currency or crypto-assets), through immediate mirroring operations with an exchange, or through a liquidity provider (Coin ATM Radar Blog).

The process, which is illustrated in Figure A3, is as follows: A customer initiates the purchase of crypto-assets in cash at a cATM. At the same time, the terminal accesses the hot wallet and sends the required amount of crypto-assets to the address provided by the customer (T1). The transaction is concluded and no further action is required. The operator periodically withdraws fiat money from the cATM (T2) and converts it into crypto-assets (T3). This operation can take place on an over-the-counter market or on an exchange. When the operator receives the purchased crypto-assets, it replenishes the balance of the hot wallet (T4), which will again be used by the cATM for other users’ operations.

Figure A3.

Sale of crypto-assets through own capital.

Figure A3.

Sale of crypto-assets through own capital.

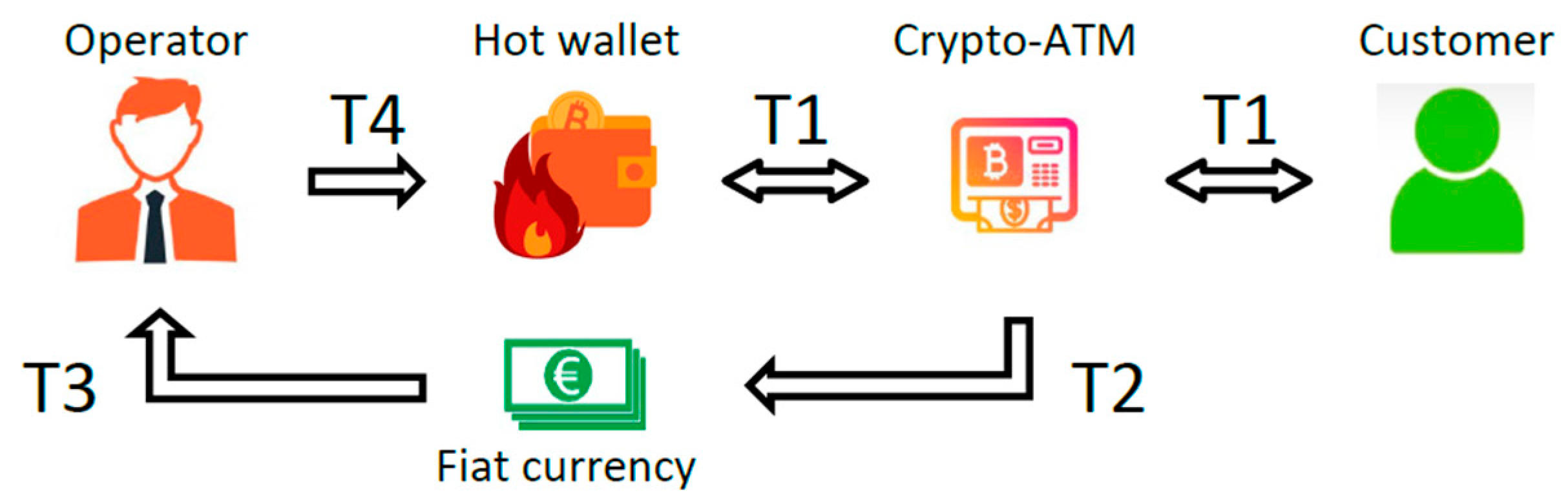

Another way of operating with a cATM is to hold a relatively small amount of crypto-assets in an operator’s hot wallet (i.e., volume for 1–2 days), while the rest of the amount is deposited in fiat currency at a crypto-asset exchange (the same hot wallet can be supported by different exchanges). The process, which is illustrated in Figure A4, is as follows: A customer initiates the purchase of crypto-assets from the cATM. At the same time, the terminal starts two processes. On the one hand, it accesses the hot wallet and sends the crypto-assets to the address provided by the customer and, on the other, using an API connection, it sends a signal to the exchange (where the operator has an open account and fiat liquidity ready to be used for trades) that purchases the same crypto-assets on the market. All of this happens simultaneously (T1) to ensure that the price is fixed at the time the customer starts the process at the cATM. After the purchase is completed, the crypto-assets are sent from the exchange balance to the operator’s hot wallet (T2) (the transition to the hot wallet can be omitted, and the crypto-assets can be sent to the user’s address directly from the exchange). The operator periodically withdraws cash from the cATM (T3), deposits it into a bank account (T4), and then transfers it to the exchange (T5) via a credit transfer, making the funds available again in the form of fiat liquidity.

Figure A4.

Immediate mirroring operations with an exchange.

Figure A4.

Immediate mirroring operations with an exchange.

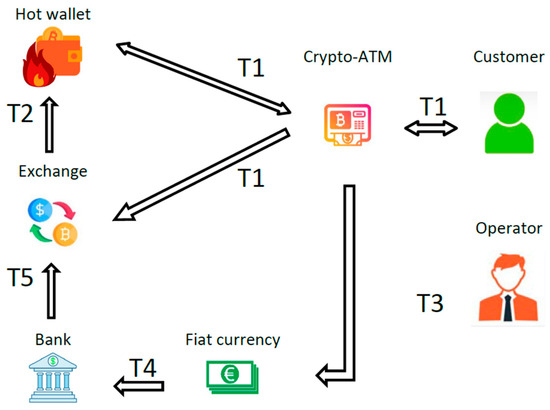

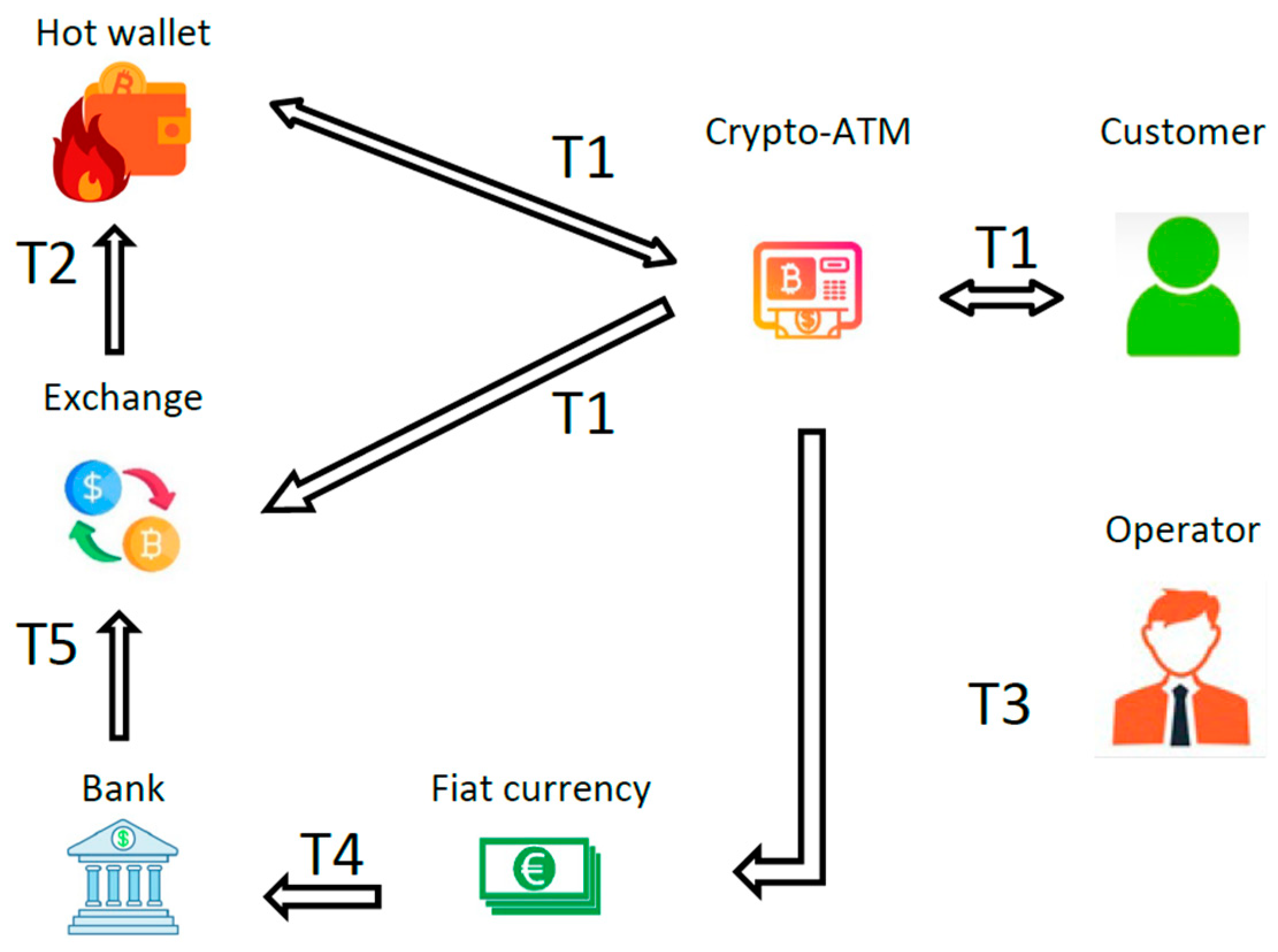

This process reduces the volume of funds held in crypto-assets in the operator’s hot wallet. The wallet can therefore have a very low balance, as it is replenished after each purchase. Ultimately, the process can be facilitated by a liquidity provider, who converts fiat currency into crypto-assets. The process, which is illustrated in Figure A5, is as follows: When the customer purchases crypto-assets at the terminal (T1), these crypto-assets are sent from the operator’s hot wallet to the customer’s wallet (T1). At the same time, information on the transaction is sent to the liquidity provider, who, without carrying out any transfer of funds, locks in the exchange rate for that specific amount (T1), giving rise to an agreement for that amount of crypto-assets. These agreements accumulate over time. The operator periodically (T2) withdraws cash from the cATM and deposits it into their bank account (T3). The liquidity provider receives the fiat funds from the operator’s bank account for the value needed via a credit transfer (T4). It then carries out the conversion based on the amounts/exchange rates of the various agreements and sends the crypto-assets to the operator’s hot wallet (T5).

Figure A5.

Operations through a liquidity provider.

Figure A5.

Operations through a liquidity provider.

Appendix B. Value of Crypto-Assets Held by PayPal Customers in the US per Quarter, 2022–2023

Table A1.

On 30 June 2022, PayPal had USD 596 m of value worth in safeguarding of crypto-assets.

Table A1.

On 30 June 2022, PayPal had USD 596 m of value worth in safeguarding of crypto-assets.

| Bitcoin (BTC) | USD 326 m |

| Ethereum (ETH) | USD 219 m |

| Other (Litecoin and Bitcoin Cash (LTC and BCH)) | USD 51 m |

| TOTAL | USD 596 m |

Table A2.

On 30 September 2022, PayPal had USD 690 m of value worth in safeguarding of crypto-assets.

Table A2.

On 30 September 2022, PayPal had USD 690 m of value worth in safeguarding of crypto-assets.

| Bitcoin (BTC) | USD 343 m |

| Ethereum (ETH) | USD 290 m |

| Other (Litecoin and Bitcoin Cash (LTC and BCH)) | USD 57 m |

| TOTAL | USD 690 m |

Table A3.

On 31 December 2022, PayPal had USD 604 m of value worth in safeguarding of crypto-assets.

Table A3.

On 31 December 2022, PayPal had USD 604 m of value worth in safeguarding of crypto-assets.

| Bitcoin (BTC) | USD 291 m |

| Ethereum (ETH) | USD 250 m |

| Other (Litecoin and Bitcoin Cash (LTC and BCH)) | USD 63 m |

| TOTAL | USD 604 m |

Note: The decrease between September and December 2022 is probably explained by the significant decline in crypto valuations following the collapse of the FTX exchange.

Table A4.

On 31 March 2023, PayPal had USD 943 m of value worth in safeguarding of crypto-assets.

Table A4.

On 31 March 2023, PayPal had USD 943 m of value worth in safeguarding of crypto-assets.

| Bitcoin (BTC) | USD 499 m |

| Ethereum (ETH) | USD 362 m |

| Other (Litecoin and Bitcoin Cash (LTC and BCH)) | USD 82 m |

| TOTAL | USD 943 m |

Table A5.

On 30 June 2023, PayPal had USD 1.016 m of value worth in safeguarding of crypto-assets.

Table A5.

On 30 June 2023, PayPal had USD 1.016 m of value worth in safeguarding of crypto-assets.

| Bitcoin (BTC) | USD 532 m |

| Ethereum (ETH) | USD 369 m |

| Other (Litecoin and Bitcoin Cash (LTC and BCH)) | USD 115 m |

| TOTAL | USD 1.016 m |

Table A6.

On 30 September 2023, PayPal had USD 877 m of value worth in safeguarding of crypto-assets.

Table A6.

On 30 September 2023, PayPal had USD 877 m of value worth in safeguarding of crypto-assets.

| Bitcoin (BTC) | USD 479 m |

| Ethereum (ETH) | USD 316 m |

| Other (Litecoin and Bitcoin Cash (LTC and BCH)) | USD 82 m |

| TOTAL | USD 877 m |

The following remarks apply to all of the tables above:

- The reports referring to the periods before Q2/2022 do not contain granular data on crypto-assets. This granularity was required by the Staff Accounting Bulletin No. 121 published on 31 March 2022.

- In all the reports, litecoin and bitcoin cash are presented in the aggregate.

- The crypto-asset valuation in USD is performed as explained in the reports: “The crypto-asset safeguarding liability and corresponding safeguarding asset are measured and recorded at fair value on a recurring basis using prices available in the market PayPal determines to be the principal market at the balance sheet date”. According to the IRFS 13 Standard, the “Fair value is the price that would be received when selling an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction in the principal (or most advantageous) market at the measurement date under current market conditions (i.e., an exit price) regardless of whether that price is directly observable or estimated using another valuation technique”.

Appendix C. Top Four Payment Protocols

Appendix C.1. Lightning Network

The Lightning Network [16] is a protocol for multiparty financial transactions with bitcoin. It was built as a second layer for bitcoin, facilitating “instant” micropayments without delegating the custody of funds to trusted third parties. (The Lightning Network was developed in an attempt to alleviate some of the drawbacks of the bitcoin network. Initial transactions confirmed on the bitcoin blockchain take up to one hour before they become irreversible. This is because bitcoin aggregates transactions into blocks spaced ten minutes apart. Payments are widely regarded as secure on bitcoin after confirmation of six blocks or after about one hour). The network itself is deployed on the internet and runs on thousands of nodes around the world. The Lightning Network aims to facilitate these “instant” payments on a blockchain through programmed automated smart contracts. This eliminates the need for individual payment transactions that congest the blockchain. Payment speed is thus improved and measured in milliseconds to seconds. The Lightning Network enables micropayments, i.e., payments of less than a few cents denominated in bitcoin (down to a price of 0.00000001 bitcoin).

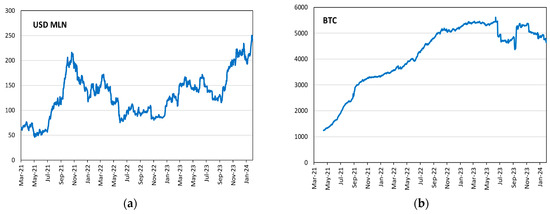

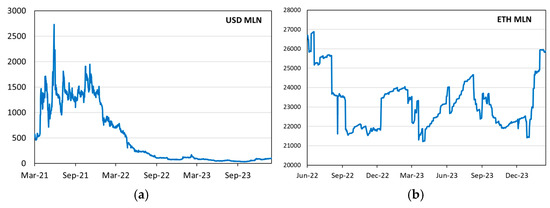

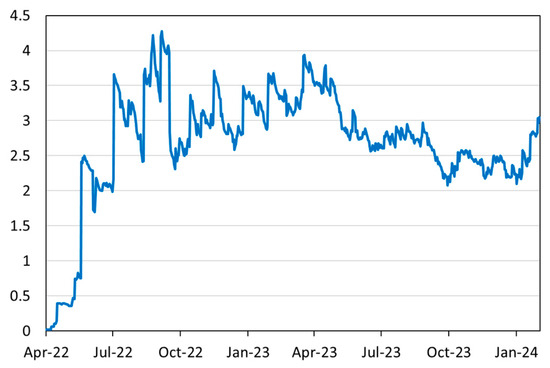

Because of its claimed scalability (millions to billions of transactions per second across the network), the Lightning Network enables machine-to-machine payments and automated micropayment services that are not possible on the bitcoin blockchain. The Lightning Network’s features and usability may explain the increase in its TVL. Figure A6a,b) show the TVL of the Lightning Network from March 2021 to early 2024 in USD and BTC, respectively. These figures show an increasing trend in the TVL in BTC and fluctuations in the TVL in USD, which are most likely due to the price fluctuations of BTC. The TVL peaked in early November 2022 at USD 215 million. From October 2023, the TVL in USD was trending upwards, with the figure of USD 212 million in early February 2024 coming close to the November 2022 peak.

Figure A6.

(a,b) Lightning Network TVL (Source: our calculation on DeFiLlama).

Figure A6.

(a,b) Lightning Network TVL (Source: our calculation on DeFiLlama).

The Lightning Network may have accelerated the adoption of bitcoin, especially considering (i) the acceptance of bitcoin as legal tender in El Salvador in September 2021 [79], (ii) the broader adoption of Lightning Network wallets for use in payments and custody, and (iii) its integration with e-commerce and payments platforms. The Lightning Network is interoperable with other crypto-asset networks that hope to improve their own scalability. Whereas the Lightning Network is based on the idea of decentralisation, in reality, centralisation seems to be increasing, as the businesses that invest in the network control it. Other issues that have been raised concerning the Lightning Network are fraud, fees, and hacks [80].

Appendix C.2. Flexa

Flexa [20] is a payment protocol that is used in the United States, Canada, and El Salvador. Flexa claims to allow for the near-instant settlement of crypto-asset transactions. A payer can use a wide variety of crypto-assets. A payee receives payment in the local fiat currency. The protocol claims to offer secured transactions with a unique, digital authorisation code that cannot be decrypted or reversed. Customers can access the mobile Flexa Spend app to connect to the network and make payments using crypto-assets, including bitcoin and ethereum. A Flexa transaction involves generating a flexcode for instant payment in the chosen crypto-asset. Recipients receive the settlement value in the fiat currency without incurring conversion fees. A sample Flexa transaction flow is presented in Figure A7. The network’s instant payment authorisations are facilitated by AMP, the network’s native token, which serves as collateral for payment decentralisation. AMP rewards token holders with more tokens for providing collateral and securing successful payment transactions. The AMP token has a maximum supply of almost 100 billion ERC-20 tokens, with approximately 42 billion tokens currently in circulation. These tokens are secured on the Ethereum network; approximately USD 280 million of these tokens are staked or deposited in other DeFi protocols. Stakeholders can lock their AMP tokens in real time to secure payment transactions on the Flexa network, independent of blockchain confirmations. Unvalidated transactions can result in the liquidation of AMP collateral to ensure payment completion.

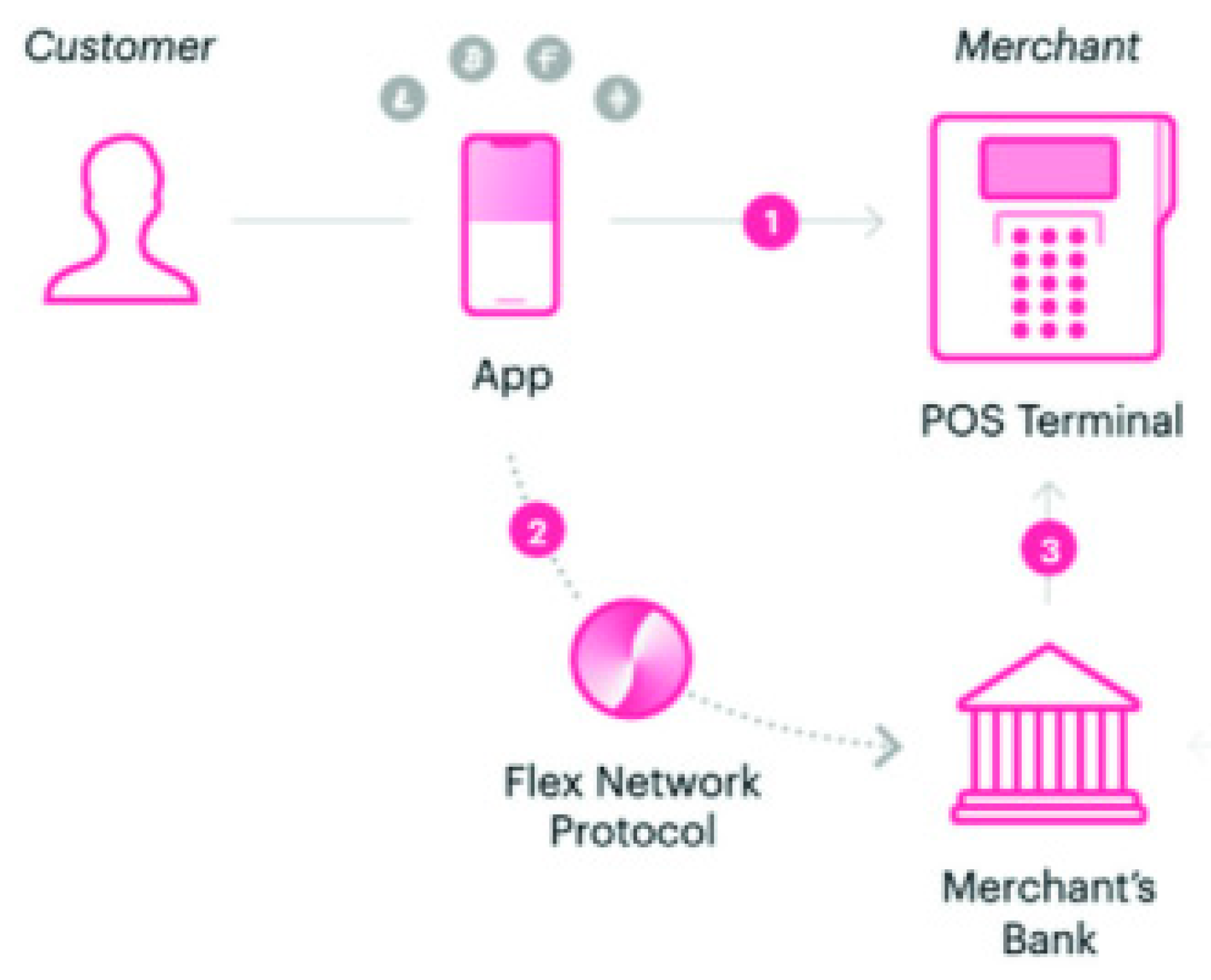

Figure A7.

Flexa transaction flow. (1) A customer scans the app at merchant POS for payment with any crypto-asset supported by Flexa. (2) The app requests the current conversion rate for the customer’s desired crypto-asset and submits a blockchain transaction via Flexa. (3) The Flexa network transmits a one-time authorisation code (FPAN) in real time to authorise the transaction on the merchant’s POS terminal, then pushes fiat funds to the merchant’s bank account. The customer’s purchase is complete (Source: Flexa Network Whitepaper [81]).

Figure A7.

Flexa transaction flow. (1) A customer scans the app at merchant POS for payment with any crypto-asset supported by Flexa. (2) The app requests the current conversion rate for the customer’s desired crypto-asset and submits a blockchain transaction via Flexa. (3) The Flexa network transmits a one-time authorisation code (FPAN) in real time to authorise the transaction on the merchant’s POS terminal, then pushes fiat funds to the merchant’s bank account. The customer’s purchase is complete (Source: Flexa Network Whitepaper [81]).

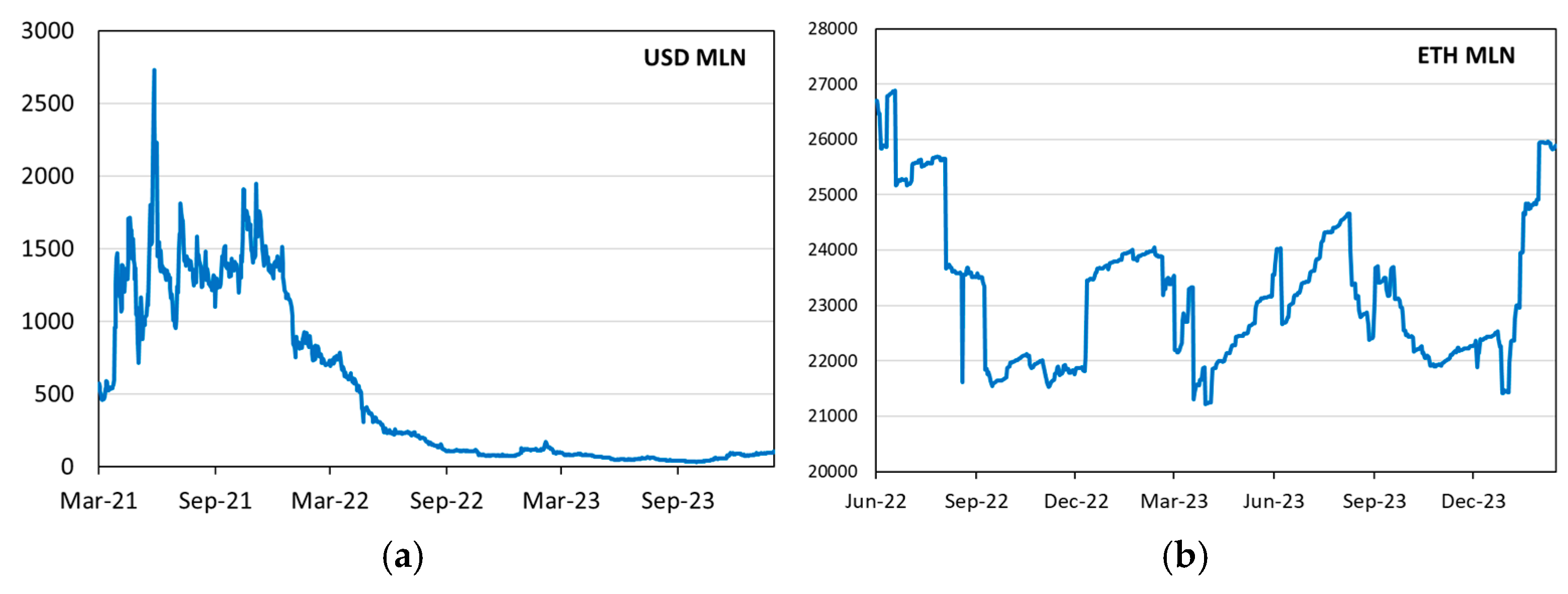

Figure A8a,b represent the TVL of Flexa in AMP tokens in USD and ETH. The values increased in 2021 when the TVL reached about USD 2.5 billion. The TVL indicator for Flexa may represent the volume of transactions, since for each transaction the same amount of AMP tokens is locked by the protocol for reimbursing possible failures. The TVL of Flexa AMP tokens at the end of 2023 was around USD 80 million.

Figure A8.

(a,b) Flexa TVL (AMP tokens) (Source: our calculation on DeFiLlama).

Figure A8.

(a,b) Flexa TVL (AMP tokens) (Source: our calculation on DeFiLlama).

Flexa has a spending limit of USD 750 per week. Furthermore, crypto-assets cannot be withdrawn instantly from the app (off-ramp), other than to be used for payments. The app and the network also have operational issues and each purchase is taxable. The Flexa app has only been downloaded 5000 times in three years since its release in 2019 on the Google Play Store. This number is much lower compared to the number of AMP holders (about 96,000) and also to the anticipation of thousands of retailers. The use of Flexa seems to be highly concentrated in terms of the numbers of users and their geographical location.

Appendix C.3. Sablier Finance

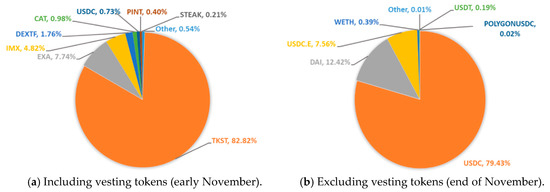

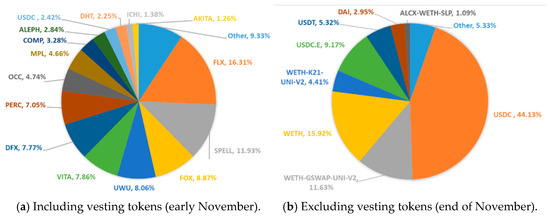

Sablier is a protocol for real-time payments based on streaming. (Streaming functionality can be explained by an hourglass, with grains of sand steadily flowing through it. By replacing the sand with crypto-assets and the hourglass with a streaming payments application, such as Sablier, we have a clear understanding of token streaming.) After a payer makes an initial deposit of crypto-assets, smart contracts start streaming the crypto-assets to the recipient. The transfers occur automatically via smart contracts with a pre-defined frequency, e.g., a fraction of the entire contract value is transferred every second from the sender to the recipient until the duration specified in the contract has ended and the contract has matured. The payee can withdraw the crypto-assets that have been transferred to his/her wallet at any time and then exchange them into fiat money. Streaming services are especially useful for use cases such as payrolls, where employees receive crypto-assets in real time for their work, instead of on a monthly basis in fiat money. Sablier is also used for vesting (vesting refers to the gradual or conditional release of tokens to stakeholders, like employees, founders, investors, or community members), airdrops (an airdrop is a marketing strategy that involves sending crypto-assets to the wallet addresses of the active members of a blockchain community for free or in return for a small service, such as retweeting a post of the company issuing the crypto-asset), and grants. The Sablier protocol was started on the Ethereum blockchain and was later also enabled on other blockchains, such as Polygon, Binance Smart Chain, Optimism, and Arbitrum. Access to the Sablier payment service is provided via an application (dApp), which provides web interfaces for streaming money and for receiving the streamed money. The application provides integration with wallets, including MetaMask and Coinbase. Sablier is governed by the Protocol admin, a collection of multisignature (MultiSig) wallets (multisignature wallets require more than one private key and add a layer of security to crypto-asset storageccessed on 2 November 2024)). The distribution of tokens varies over time. Figure A9a,b show the distribution of the TVL of Sablier V2 tokens in November 2023. If vesting tokens (Vesting tokens are a type of digital asset that are gradually released to the holders over a period of time, according to a predefined schedule; they are often used to incentivise the long-term commitment and alignment of interests of the stakeholders of a crypto-asset project, such as the founders, team members, investors, or community members. Vesting tokens can have different terms and conditions, such as cliff periods, linear or non-linear release rates, and revocability clauses, and can affect the circulating supply and the market value of a crypto-asset, depending on the demand and supply dynamics. (https://coinmarketcap.com/alexandria/article/what-does-vesting-mean-in-crypto—accessed on 2 November 2024)) are included, the token with the highest TVL was TokenSight (TKST), a crypto-asset that was launched on 28 October 2023 for the TokenSight vesting program. Sablier V2 TVL showed a significant increase from USD 2 million to almost USD 50 million during that period. This increase can be explained by the launch of TKST and the TokenSight vesting program (https://blog.sablier.com/how-tokensight-leverages-sabliers-vesting-solution// (accessed on 2 November 2024)). More specifically, TKST locked up over 80% of its token supply in Sablier’s token distribution protocol. However, the distribution of the Sablier V2 TVL in the supported tokens was different at the end of November 2023, after the vesting processes had started and the TKST tokens were unlocked and transferred to the vesting streams.

Figure A9.

TVL distribution of Sablier V2 tokens (November 2023) (Source: our calculation on DefiLlama dataset).

Figure A9.

TVL distribution of Sablier V2 tokens (November 2023) (Source: our calculation on DefiLlama dataset).

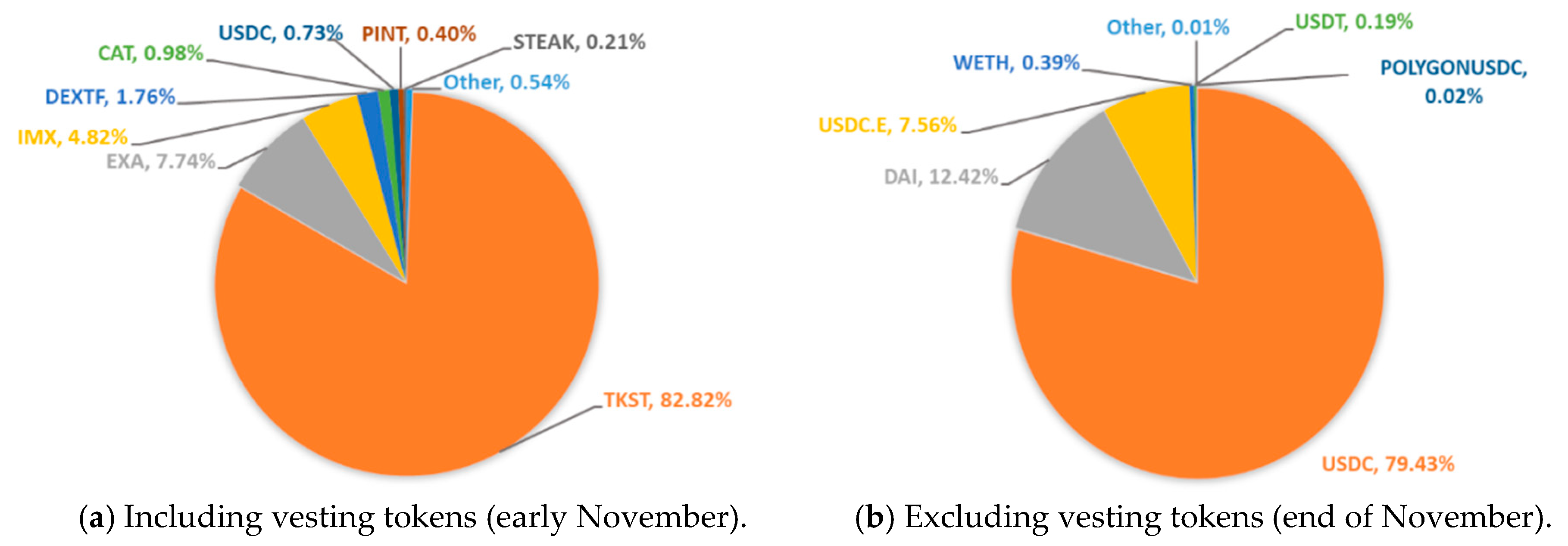

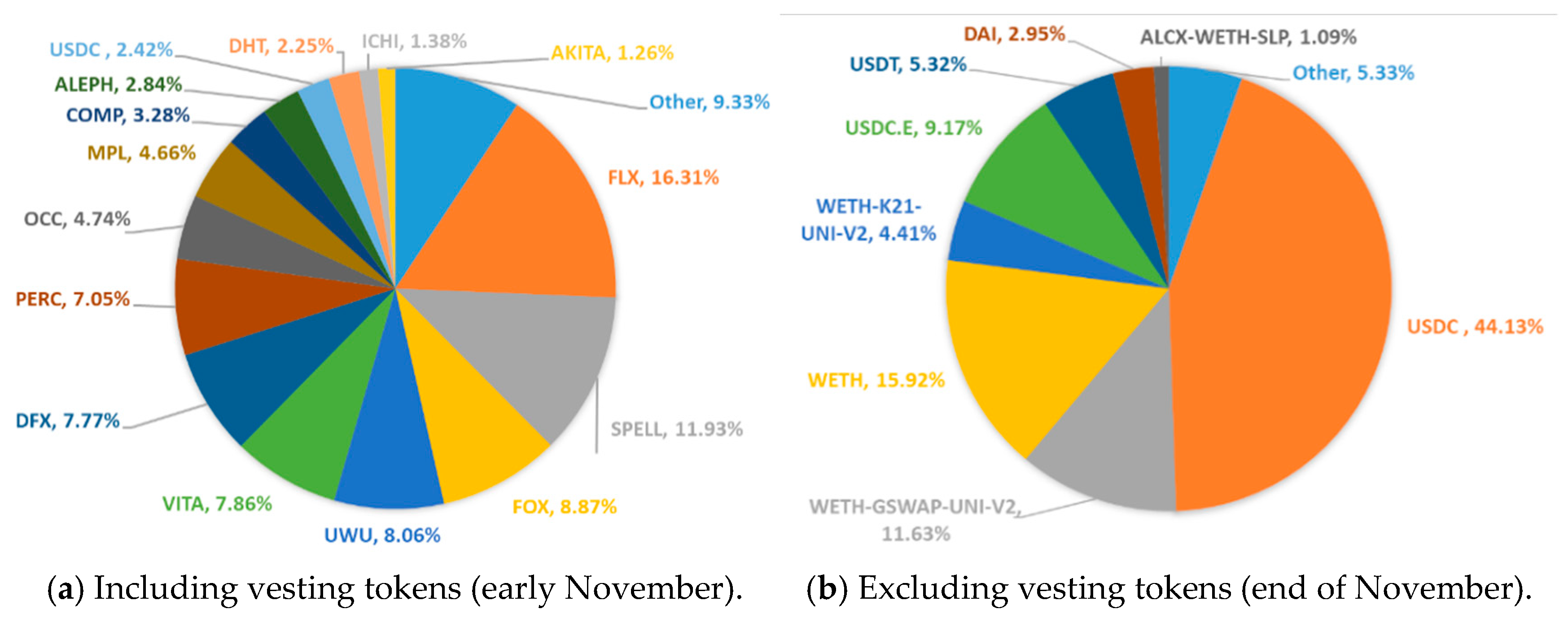

A different distribution of tokens can be seen for Sablier V1, which also varied over time (Figure A10a,b).

Figure A10.

TVL distribution of Sablier V1 tokens (November 2023) (Source: our calculation on DefiLlama dataset).

Figure A10.

TVL distribution of Sablier V1 tokens (November 2023) (Source: our calculation on DefiLlama dataset).

Appendix C.4. LlamaPay

LlamaPay [18] is a multi-chain protocol (Multi-chain is a process where projects deploy smart contracts across multiple blockchains, connecting isolated chains together as one network. This differs from regular chains, such as Bitcoin or Ethereum, each of which are individual chains. Retrieved from https://www.techopedia.com. (accessed on 2 November 2024)) that also enables money streaming. Unlike Flexa, the users (recipients) of Llama Pay can withdraw their received crypto-assets at any time. LlamaPay is used as an automated salary streaming protocol, where salaries can be paid to employees for every second they work. It is currently used by Yearn Finance, Convex Finance, and SpookySwap. Figure A11 presents its TVL, which was about USD 2.4 million at the end of 2023 (fourth protocol in TVL ranking of payment protocols).

Figure A11.

LlamaPay TVL (in USD MLN) (Source: our calculation on DeFiLlama).

Figure A11.

LlamaPay TVL (in USD MLN) (Source: our calculation on DeFiLlama).

References

- Al Reshaid, F.; Tosun, P.; Gürce, M.Y. Cryptocurrencies as a means of payment in online shopping. Digit. Policy Regul. Gov. 2024, 26, 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindseil, U.; Schaaf, J.G. The Distributional Consequences of Bitcoin. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4985877 (accessed on 2 November 2024).

- Chaudhari, B. The Role of Cryptocurrencies in the Future of Global Payments. IJCRT 2024, 12, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Adrian, T.; Mancini-Griffoli, T. The rise of digital money. Annu. Rev. Financ. Econ. 2021, 13, 57–77. [Google Scholar]

- MiCAR: Regulation (EU) 2023 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 31 May 2023 on Markets in Crypto-Assets. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32023R1114 (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Al-Amri, R.; Zakaria, N.H.; Habbal, A.; Hassan, S. Cryptocurrency adoption: Current stage, opportunities, and open challenges. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Res. 2019, 9, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayani, U.; Hasan, F. Unveiling Cryptocurrency Impact on Financial Markets and Traditional Banking Systems: Lessons for Sustainable Blockchain and Interdisciplinary Collaborations. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2024, 17, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busse, K.; Tahaei, M.; Krombholz, K.; von Zezschwitz, E.; Smith, M.; Tian, J.; Xu, W. Cash, Cards or Cryptocurrencies? A Study of Payment Culture in Four Countries 2020. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE European Symposium on Security and Privacy Workshops (EuroS&PW), Genoa, Italy, 7–11 September 2020; pp. 200–209. [Google Scholar]

- Okeke, N.; Achumie, G.O.; Ewim, S. Adoption of cryptocurrencies in small and medium-sized enterprises: A strategic approach to enhancing financial inclusion and innovation. Int. J. Front. Sci. Technol. Res. 2024, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, M.; Bento Pereira Da Silva, P.; Born, A.; Cappuccio, M.; Czák-Ludwig, S.; Gschossmann, I.; Paula, G.; Pellicani, A.; Philipps, S.; Plooij, M.; et al. Stablecoins’role in Crypto and Beyond: Functions, Risks and Policy. 2022. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/financial-stability-publications/macroprudential-bulletin (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- European Central Bank. A Big Future for Small Payments?—Micropayments and Their Impact on the Payment Ecosystem, European Central Bank, 2023. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2866/07262 (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT): Definition and How It Works. Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/d/distributed-ledger-technology-dlt.asp (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Li, Y.; Cao, B.; Peng, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Feng, D.; Yu, J. Direct Acyclic Graph-based Ledger for Internet of Things: Performance and Security Analysis. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2020, 28, 1643–1656. [Google Scholar]

- IOTA. Available online: https://files.iota.org/comms/IOTA_Use_Cases.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- BraveSoftware. Available online: https://brave.com/ (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Lightning Network. Available online: https://lightning.network/ (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Sablier. Available online: https://sablier.com/ (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- LamaPay. Available online: https://llamapay.io/ (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Settlement Finality Directive (Directive 98/26/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 May 1998 on Settlement Finality in Payment and Securities Settlement Systems). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:31998L0026 (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Flexa. Available online: https://wiki.defillama.com/wiki/Flexa (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Committee of Payments and Market Infrastructures-BIS. Enhancing Cross-Border Payments: Building Blocks of a Global Roadmap—Stage 2 Report to the G20, July 2020. Available online: https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d193.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Committee of Payments and Market Infrastructures-BIS. Considerations for the Use of Stablecoin Arrangements in Cross-Border Payments, October 2023. Available online: https://www.bis.org/cpmi/publ/d220.pdf (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Kosse, A.; Glowka, M.; Mattei, I.; Rice, T. Will the Real Stablecoin Please Stand Up? BIS Papers No. 141, 2023. Available online: https://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap141.htm (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- ECB Glossary. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/services/glossary/html/act7z.en.html (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- iDEAL. Available online: https://www.ideal.nl/en/ (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Klarna. Available online: https://www.klarna.com/us/what-is-klarna/ (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Swish. Available online: https://www.swedbank.se/en/private/cards-and-payment/swish.html (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Bankgiro. Available online: https://www.bankgirot.se/en/about-bankgirot/our-offer/payment-systems/bankgiro-system/ (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Binance. Available online: https://www.binance.com/en (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Frequently Asked Questions on Binance Card EEA Program Closure|Binance Support. Available online: https://www.binance.com/en/support/faq/frequently-asked-questions-on-binance-card-eea-program-closure-d6c54984df904db7a0705f2914827381 (accessed on 2 January 2025).