Review of Togolese Policies and Institutional Framework for Industrial and Sustainable Waste Management

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. An Overview Solid Waste Management Laws in Togo

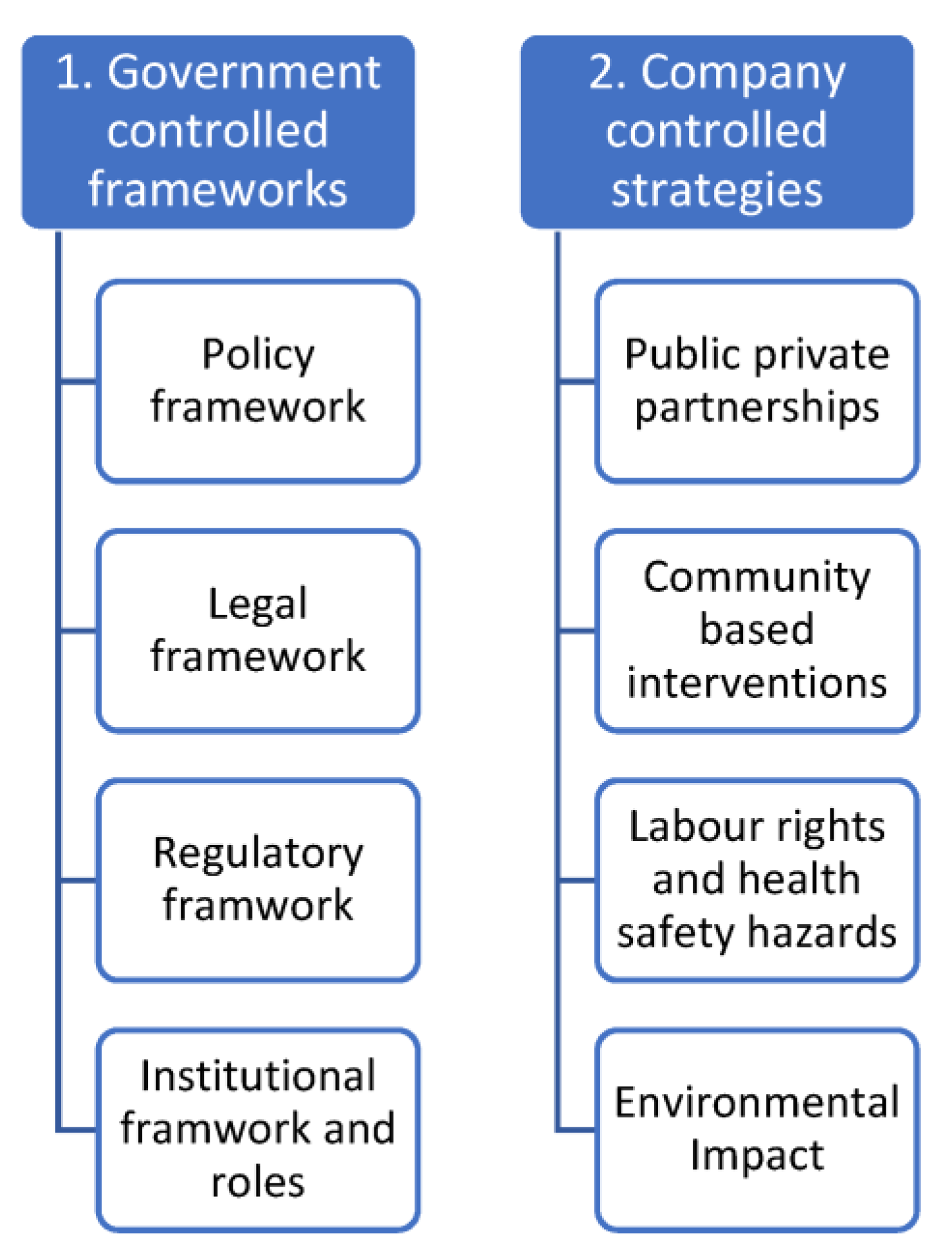

1.2. Green Industrial Companies

2. Research Methods

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Policies for the Management of Green Industrial Companies in Togo

3.1.1. Legal Framework for the Management of Green Industrial Companies in Togo

3.1.2. Regulatory Framework for Management of Green Industrial Companies in Togo

- To protect most people from high daytime noise, the sound intensity levels on balconies, terraces, and outdoor living areas should not exceed 55 dB LAeq for continuous background noise.

- To protect many people from moderate daytime nuisances, the outdoor sound intensity level should not exceed 50 dB LAeq.

- At night, the sound intensity levels on the exterior façades of living spaces should not exceed 45 dB LAeq and 60 dB LAMax, so people can sleep with the windows open. These values were obtained assuming that the reduction in noise from outside to inside with partially open windows is 15 dB.

3.1.3. Institutional Framework for Management of Green Industrial Companies in Togo

- Public Private Partnership

- 2.

- Community-based strategies

- 3.

- Business models in waste management and creation of circular economy

- 4.

- For labor rights, health and safety standards for the health, safety, and well-being of the workforce, and to support the long-term economic growth of society, it is crucial to provide a workplace that adheres to hygienic and sanitation standards [55].

- 5.

- Ensuring standards and reducing negative environmental impact

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Matsunaga, K.O.; Themelis, N.J. Effects of affluence and population density on waste generation and disposal of municipal solid wastes. Earth Eng. Cent. Rep. 2002, pp. 1–28. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228908198_Effects_of_affluence_and_population_density_on_waste_generation_and_disposal_of_municipal_solid_wastes (accessed on 2 September 2002).

- World Bank Data. GDP Growth (Annual %)—Togo—World Bank Data. 8 December 2022. [Enligne]. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Bigou-Lare, N.; Pigé, B. Chapitre 18. La gestion des ordures ménagères à Lomé. Dyn. Norm. 2015, pp. 219–228. Available online: https://www.cairn.info/dynamique-normative--9782847698251-page-219.htm (accessed on 3 October 2019).

- Ayodele, T.R.; Alao, M.A.; Ogunjuyigbe, A.S.O. Recyclable resources from municipal solid waste: Assessment of its energy, economic and environmental benefits in Nigeria. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 134, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salguero-Puerta, L.; Leyva-Díaz, J.C.; Cortés-García, F.J.; Molina-Moreno, V. Sustainability indicators concerning waste management for implementation of the circular economy model on the University of Lome (Togo) Campus. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bitasse, E.O.; Moutoré, Y.; Dansoip, G. Stakeholders’ perceptions and strategies to climate change resilience in Kara and Dapaong, Togo. In Natural Resources, Socio-Ecological Sensitivity and Climate Change in the Volta-Oti Basin; West Africa CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Azianu, K.A.; Sangli, G. Challenges of health care waste management in the health district n° 5 of Lomé Commune in Togo. HAL 2021, 15, 90–105. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, M.D.; Pushkareva, L. Implementation of the law on solid waste management in Vietnam today: Necessity, problem and solutions. E3S Web Conf. 2020, 164, 11013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnaro, T.; Ali, A.; Adom, A.; Abiassi, E.S.; Degbey, C.; Douti, Y.; Messan, D.K.; Sopoh, G.E.; Ekouevi, D.K. Assessing Biomedical Solid and Liquid Waste Management in University Hospital Centers (CHU) in Togo, 2021. Open J. Epidemiol. 2022, 12, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouattara, J.M.P.; Zahui, F.M.; Messou, A.; Loes, L.M.E.; Coulibaly, L. Assessment of Solid Waste Management Practices in Public Universities in Developing Countries: Case of NANGUI ABROGOUA University (Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire). Int. J. Waste Resour. 2022, 12, 451. [Google Scholar]

- Amato, C.; Togo, C. Improper Municipal Solid Waste Disposal and The Environment in Urban Zimbabwe: A Case of Masvingo City. Ethiop. J. Environ. Stud. Manag. 2021, 14, 554–564. [Google Scholar]

- Bilgaev, A.; Dong, S.; Li, F.; Cheng, H.; Sadykova, E.; Mikheeva, A. Assessment of the current eco-socio-economic situation of the baikal region (Russia) from the perspective of the Green economy development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, N.C.; England, J.R.; Newnham, G.J.; Alexander, S.; Green, C.; Minelli, S.; Held, A. Developing good practice guidance for estimating land degradation in the context of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 92, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.J.; Choi, T.M.A. United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals perspective for sustainable textile and apparel supply chain management. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2020, 141, 102010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Europeen Ttransition. Officer. ESA Climate Office. 9 November 2022. [Enligne]. Available online: https://climate.esa.int/en/news-events/estimating-national-greenhouse-gas-emissions-and-sinks-for-the-global-stocktake/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- ODD. Forum Politique de Haut Niveau sur le Developpement Durable; ODD: New York, NY, USA, 2017. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/fr/how-we-work/intergovernmental-support/hlpf-on-sustainable-development (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- A/SA.2/07/13; Acte Additionnel. Politique en Matière d’Efficacité Énergétique de la CEDEAO (PEEC). Chez Politique d’Efficacité Énergétique de la CEDEAO (PEEC): Abuja, Nigeria, 21 June 2013. Available online: https://www.ifdd.francophonie.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/727_LEF-107-2.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- NGOM; Mbissane. Intégration régionale et politique de la concurrence dans l’espace CEDEAO. In Proceedings of the Chez L’évolution Normative de la CEDEAO en Matière, Abuja, Nigeria, 19 December 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ministere de L’environnement et des Ressources Forestieres. Politique Nationale de l’Environnement, chez La politique nationale de l’environnement, adoptée par le Gouvernement; Ministere de L’environnement et des Ressources Forestieres: Lome, Togo, 23 December 1998. Available online: https://environnement.gouv.tg/wp-content/uploads/files/2018/Septembre/POLITIQUE%20FORESTIERE%20DU%20TOGO%20(PFT)%202011-2035.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- Boliko, M.C. FAO and the situation of food security and nutrition in the world. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 2019, 65, S4–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehof, L.A. Guide to the Travaux Préparatoires of the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Water. Water and Climate Change; The United Nations World Water Development Report; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guilherme, J.L.; Jones, V.R.; Catry, I.; Beal, M.; Dias, M.P.; Oppel, S.; Vickery, J.A.; Hewson, C.M.; Butchart, S.H.M.; Rodrigues, A.S.L. Connectivity between countries established by landbirds and raptors migrating along the African–Eurasian flyway. Conserv. Biol. 2023, 37, e14002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfredo, E.I.; Nurcahyo, R. The impact of ISO 9001, ISO 14001, and OHSAS 18001 certification on manufacturing industry operational performance. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Bandung, Indonesia, 6–8 March 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Johnsson, F.; Karlsson, I.; Rootzén, J.; Ahlbäck, A.; Gustavsson, M. The framing of a sustainable development goals assessment in decarbonizing the construction industry–Avoiding “Greenwashing”. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 131, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsani, S.; Koundouri, P.; Akinsete, E. Resource management and sustainable development: A review of the European water policies in accordance with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 114, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P2-P2RS, PPCI-Sahel. Politique Nationale d’Hygiène et d’Assainissement au Togo. chez Politique Nationale de l’Aménagement du Territoire (PONAT); P2-P2RS, PPCI-Sahel: Lome, Togo, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ministere des Mines et de L’energie. Plan Actions National d’Efficacité Energétique (PANEE) TOGO. chez Plan Actions National d’Efficacité Energétique (PANEE); Ministere des Mines et de L’energie: Lome, Togo, 2015. Available online: https://www.se4all-africa.org/fileadmin/uploads/se4all/Documents/Country_PANEE/Togo_Plan_d_Actions_National_d%E2%80%99Efficacite%CC%81_Energe%CC%81tique.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- ANCR-GEM. Bilan de la mise en œuvre de la CCNUCC au Togo et besoins en renforcement des capacités. In Proceedings of the Chez Convention Cadre des Nations Unies sur les Changements Climatiques, Lome, Togo, 8 March 1995. [Google Scholar]

- GmbH; GIZ Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ). Plan National d’Adaption Aux, Chez Plan National d’Adaption Aux; GmbH: Bonn et Eschborn, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Republique Togolaise. Troisième Communication Nationnale Du Togo au titre de la CCNUCC (Title: Appui au déploiement du projet « Lumières authentiques pour chaque maison au Togo. Proceedings of the Chez Troisieme Communication Nationale, Lome, Togo, 6 January 2017; Available online: https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ctc-n.org%2Fsites%2Fwww.ctc-n.org%2Ffiles%2Frequest%2Ftogo_-_req_ctcn_ref_2017000009_rev04042018-abd.doc&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- Conférence internationale du Travail. Organisation internationale du Travail C 176. Convention de l’OIT sur la sécurité et la santé dans les mines, 1995 (n° 176). chez C 176. Convention de l’OIT sur la sécurité et la santé dans les mines, 1995 (n° 176), Genve, 110e session. 2022. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/fr/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:14001:0::NO::P14001_INSTRUMENT_ID:312321 (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- C176-Convention (n° 176). La sécurité et la santé dans les mines, 1995. Proceedings of the Chez La Conférence Générale de l’Organisation Internationale du Travail, Genève, Switzerland, 6 June 1995; Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/fr/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C176 (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- Republique, President de la, Constitution De La Iv’ Republique; Journal Officiel De La’republîque Togolaise: Lome, Togo, 1992. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/SERIAL/38025/95144/F1715143836/Constitution%201992.pdf (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- Loi-N°2007-011. Loi n° 2007-011 du 13 Mars 2007 Relative à la Décentralisation et aux Libertés Locales; Journal Official: Lome, Togo, 13 March 2007; pp. 1–32. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/natlex4.detail?p_lang=en&p_isn=76216&p_country=TGO&p_count=243 (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- LOI-nº-00919/06. Eaux—Forêts—Environnement, Spécial. 19 June 2008; p. 20.

- Législation-n°2016-002. Loi n°2016-002 du 04 Juin 2016 Portant Loi-Cadre sur L’aménagement du Territoire, Environnement gén.; Terre et sols; Mer. 4 June 2016.

- LegislationLoi nº2008-005. Loi nº 2008-005 du 30 mai 2008 portant loi-cadre sur l’environnement. J. Off. République Togol. 2008, 19, 1–18.

- Loin°2021-012du. Code du Travail de la République Togolaise, 18 June 2021.

- Législation-nº2009-007. Loi nº 2009-007 portant Code de la santé de la République togolaise. J. Off. République Togol. 2009, pp. 1–57. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/fr/c/LEX-FAOC093366/ (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- ADA–GAIC, Groupement. Cadre de Gestoion Environnementale et Sociale Togo, Programme de Renforcement de la Resilience a l’insecurite Alimentaire et Nutritionnelle au Sahel (p2-p2rs, Ppci-Sahel, 2020–2025), 16 March 2011; 175p.

- MTESS/MS. Portant Création de Service de Sécurité et Santé au Travail. pris Conformément aux Articles 175 et 178 du code du Travail, 7 October 2011.

- Primature. Membres du Gouvernement. 2020. [Enligne]. Available online: https://primature.gouv.tg/gouvernement/ (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- Législation. Décret n° 2019-130/PR du 09 Octobre 2019 Fixant les Modalités D’organisation et de Fonctionnement du Fonds d’Appui aux Collectivités Territoriales (FACT). 2019-10-09. 26 June 2019. [Enligne]. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/fr/c/LEX-FAOC191842/ (accessed on 12 December 2019).

- Joseph, S.; Jenkin, E. The United Nations Human Rights Council: Is the United States Right to Leave this Club? Am. U. Int’l L. Rev. 2019, 35, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Дешкo, Л. National Institutions Established in Accordance with the Paris Principles, Engaged into the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights in the System of Internal Means of Security. Кoнституційнo-Правoві Академічні Студії. 2020, p. 2. Available online: http://journal-kpas.uzhnu.edu.ua/article/view/231403 (accessed on 11 May 2023).

- Maestro, M.; Pérez-Cayeiro, M.L.; Chica-Ruiz, J.A.; Reyes, H. Marine protected areas in the 21st century: Current situation and trends. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2019, 171, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Päivinen, R.; Lindner, M.; Rosén, K.; Lexer, M.J. A concept for assessing sustainability impacts of forestry-wood chains. Eur. J. For. Res. 2012, 131, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Sadiq, N.; Anwar, S.; Qazi, U. Consumer choice of health facility among the lowest socioeconomic group in newly established demand-side health-financing scheme in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. East Mediterr Health J. 2021, 27, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, T.E.; De-Souza, E.D.; Destro, I.R.; Hammes, G.; Rodriguez CM, T.; Soares, S.R. How the combination of Circular Economy and Industry 4.0 can contribute towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsolakis, N.; Niedenzu, D.; Simonetto, M.; Dora, M.; Kumar, M. Supply network design to address United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: A case study of blockchain implementation in Thai fish industry. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 131, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amr, M.S.M. The Role of the International Court of Justice as the Principal Judicial Organ of the United Nations; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Has China Established a Green Patent System? Implementation of Green Principles in Patent Law. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, M.; Jaggi, B. Global warming disclosures: Impact of Kyoto protocol across countries. J. Int. Financ. Manag. Account. 2011, 22, 46–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutanto, E.M.; Kurniawan, M. The impact of recruitment, employee retention and labor relations to employee performance on batik industry in Solo City, Indonesia. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2016, 17, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Title Date | Date Issued | Issuing Agency | Content | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Law | Law on Environmental Protection. | 2009 | National Assembly of Togo. | This law was created to address environmental protection activities, such as environmental rights, obligations, and responsibilities of agencies, organizations, families, and individuals. Environmental protection activities also include policies, measures, and resources to safeguard the environment. |

| Strategies | National strategy on integrated solid waste management to 2025, with a vision to 2050. | 2022 | Municipal Authorities. | The overall objective of this strategy was to build an integrated solid waste management system by 2024 that sorts solid waste at the source. Using relevant and cutting-edge technologies, waste collection, reuse, recycling, and treatment will be carefully controlled to minimize the amount of waste in landfills and lower environmental damage. |

| Solid waste development strategy in urban areas and industrial zones in Togo to 2022. | 2020 | Municipal Authorities. | This strategy’s goals are to collect, transport, and treat between 70% and 85% of the total solid waste by 2030. | |

| National program | Solid waste treatment investment program for the period 2011–2020. | 2021 | Municipal Authorities. | The program’s objective is to mobilize and concentrate resources toward solid waste treatment investments to increase the effectiveness of solid waste management, enhance environmental quality, protect public health, and contribute to the nation’s sustainable development. |

| Decree | Decree on waste and scrap management. | 1984 | Ministry of Environment. | The management of waste, including hazardous waste, home waste, common industrial solid waste, liquid waste, wastewater, industrial emissions, and other specific wastes, is covered by this decree. Importing scrap metal is also covered by environmental protection. |

| Decision | Announce regulations on MSW collection, transportation, and treatment. | 2009 | The Government. | Street sweeping, waste collection, transportation, and treatment requirements, as well as rules for household solid waste, construction waste, and medical solid waste, are all included in this ruling. |

| Policy Laws | Policy Objective on Waste and Energy |

|---|---|

| The Strategic Framework of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [27,28] | The SDGs have identified 15 priority objectives to address poverty, hunger, access to energy services, economic growth, employment, building resilient infrastructure, and climate change. |

| ECOWAS Energy Efficiency Policy (ESCP) [29] | The policy aims to improve ECOWAS’ energy efficiency to international standards by 2020 through five regional initiatives. |

| ECOWAS Environmental Policy [30] | The ECOWAS Environmental Policy seeks to improve the living conditions of people in sub-regional areas. |

| Togo’s national environmental policy [31] | Togo’s national environmental policy aims to promote rational management of natural resources and the environment, with four main orientations. (1) De-concentration of industrial units, (2) legislation, (3) environmental assessment, and (4) low-impact mining. |

| Togo’s National Sanitation and Hygiene Policy | Strengthen national capacities, develop local expertise, ensure full coverage of sanitation facilities, and foster a culture of hygiene and sanitation. |

| National Spatial Planning Policy (PONAT) [32] | Improve national governance of environmental management, bring coherence to policies, plans, and policies, and promote an environmental ethic through public awareness. |

| TOGO’s action plan on renewable energy [33] | Energy efficiency and sustainable energy for all focuses on three priorities. Increase energy supply, strengthen security, reduce inequalities in access to modern energy services. |

| Legal Framework | Legal Framework Objective on Waste and Energy |

|---|---|

| International Legal Framework (ILF) in Togo | |

| United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) [34] | Stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere to prevent any disturbance of the climate and stabilize GHG concentrations in the atmosphere to prevent dangerous anthropogenic disturbance of the climate system. |

| The Kyoto Protocol [35] | Establishes a “clean” development mechanism to help developing countries and Annex I Parties meet their emission reduction and limitation commitments |

| The Paris Agreement [36] | Aims to contain global warming below 2 °C and to achieve carbon neutrality by reducing GHG emissions to offset them by carbon sinks in the second half of the century. The Paris Agreement emphasizes the distinction between developed and developing countries, setting a $100 billion ceiling for climate assistance by 2025. |

| International Labor Organization Convention 176 on Mining [36] | International Labor Organization Convention 176 on Mining prohibits all forms of child labor in mines and advocates for immediate action to eliminate the worst forms of child labor. Types of work must be determined by national legislation or competent authority. |

| The Convention on the Promotional Framework for Safety and Health at Work [37] | Members must take active measures to ensure a safe and healthy working environment. |

| National Legal Framework (NLF) | |

| The Togolese Constitution of the 4th Republic of 1992 [38] | Recognizes the citizens’ right to a healthy environment and imposes special obligations on the State to protect it. It also considers the environmental rights and duties set out in the 1945 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and international instruments ratified by Togo. |

| Environmental Framework Act 2008-005 of 30 May 2008 [39] | Preserve and sustainably manage the environment, guarantee an ecologically healthy living environment, create conditions for rational and sustainable management of natural resources, and improve the living conditions of the population. |

| Law No. 2018 correcting Law No. 2007-011 of 13 March 2007 on decentralization and local freedoms [40] | Confers important powers on local authorities to manage the environment and natural resources, including sanitation and environmental health measures. |

| Law No. 2008-009 of 19 June 2008 on the Forest Code [41,42]. | Defines and harmonizes the rules for the management of forest resources for a balance of ecosystems and the sustainability of forest heritage. It also prohibits any act that harms or disturbs wildlife or habitats, along with hunting, fires, and bushfires. |

| The Planning Framework Law [43] | Focuses on unity, national solidarity, economic and social cohesion, complementarity, sustainability of development, participation of all actors, subsidiarity, and regional integration. |

| Law No.2009-007 of 15 May 2009 on the public health code [44] | Protects the environment, including water and air pollution |

| Regulatory Order No 2011-041/PR [45] | Regulatory Order No 2011-041/PR outlines steps for carrying out Togo’s environmental and social impact assessment. Audit must be conducted every four years following environmental compliance certificate. |

| Regulatory Order No 2012-043/PR [46] | Regulatory Order No 2012-043/PR revises tables of occupational diseases, defining them as an ailment deriving from working circumstances. |

| Inter-ministerial Agreement No.004/2011/MTESS/MS [47] | Establishes an occupational safety and health service to identify and assess risks, monitor risk factors, and draw up statistics. |

| Inter-ministerial Agreement No.005/2011/MTESS/MS | Employers must submit their employees to medical examinations for employment and periodic examinations at least once a year, with employer responsibility for costs. |

| Inter-ministerial Agreement No.009/2011/MTESS/DGTLS of 26 May 2011 | The Technical Advisory Committee on Safety and Health at Work is responsible for identifying risks, ensuring compliance, carrying out investigations, and improving health and safety conditions. |

| Inter-ministerial Agreement No.2000-090/PR | Application for operating authorization must be sent to Regulatory Authority three months before commissioning. |

| N° | Institutions | Role in the Management of GIC |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ministry of Environment and Forest Resources | Implementation of the national environmental policy is ensured by the ministry in charge of the environment. |

| 2 | Ministry of Energy and Mines | Implementation of State policy in the area of mines, hydrocarbons, and energy and ensures its follow-up with the collaboration of other ministries and institutions concerned. |

| 3 | Ministry of Road, Rail and Air Transport | Coordinates the interventions of the State and the various actors in the construction of public works and oversees the management of the maintenance, rehabilitationm and promotion of road, airport, rail, port, and rural track infrastructures. They are responsible for the public engineering and architecture activities entrusted to his services. |

| 4 | Ministry of Security and Civil Protection | Implements government policies in matters of protection of persons and property, civil security, security of institutions, and maintenance of public order and peace. |

| 5 | Ministry of Public Service, Labor and Social Dialogue | Prepares labor relations legislations and regulations and oversees their applications. Ensures the quality of relations between workers and employers and promotes social dialogue. Defines the strategy for combating unemployment, underemployment, child labor, and illegal work. Promotes fundamental principles and rights at work, labor migration, and conflict management in the workplace Implements a policy for the development of social cover for workers. Monitors the proper functioning of social security and health insurance bodies. |

| 6 | Ministry of Territorial Administration, Decentralization and Territorial Development | Develops implements, conducts and executes government policy in the areas of territorial administration, the conduct of the decentralization process, and the management of local authorities. Ensures respect for the distribution of powers between the State and the local authorities and works to safeguard the general interest and legality. |

| 7 | Ministry of Health, Public Hygiene and Universal Access to Care | Develops programs to improve health coverage as well as strategies for the prevention and control of major endemics. Ensures the permanence and continuity of the functioning of health services and ensures easy and equitable access to health care. |

| 8 | Ministry of Trade, Industry and Local Consumption | |

| 9 | ANGE-(National Environmental Management Agency) | |

| Company | Green Strategy |

|---|---|

| Substitution of fossil fuels (coal) with waste alternative fuel biomass from local farms |

| Substitution of fossil fuels (coal) with waste alternative fuel from local waste oil |

| Substitution of fossil fuels (Diesel) with waste alternative fuel from local farmer waste |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beguedou, E.; Narra, S.; Agboka, K.; Kongnine, D.M.; Afrakoma Armoo, E. Review of Togolese Policies and Institutional Framework for Industrial and Sustainable Waste Management. Waste 2023, 1, 654-671. https://doi.org/10.3390/waste1030039

Beguedou E, Narra S, Agboka K, Kongnine DM, Afrakoma Armoo E. Review of Togolese Policies and Institutional Framework for Industrial and Sustainable Waste Management. Waste. 2023; 1(3):654-671. https://doi.org/10.3390/waste1030039

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeguedou, Essossinam, Satyanarayana Narra, Komi Agboka, Damgou Mani Kongnine, and Ekua Afrakoma Armoo. 2023. "Review of Togolese Policies and Institutional Framework for Industrial and Sustainable Waste Management" Waste 1, no. 3: 654-671. https://doi.org/10.3390/waste1030039

APA StyleBeguedou, E., Narra, S., Agboka, K., Kongnine, D. M., & Afrakoma Armoo, E. (2023). Review of Togolese Policies and Institutional Framework for Industrial and Sustainable Waste Management. Waste, 1(3), 654-671. https://doi.org/10.3390/waste1030039