The Current Status of OCT and OCTA Imaging for the Diagnosis of Long COVID

Abstract

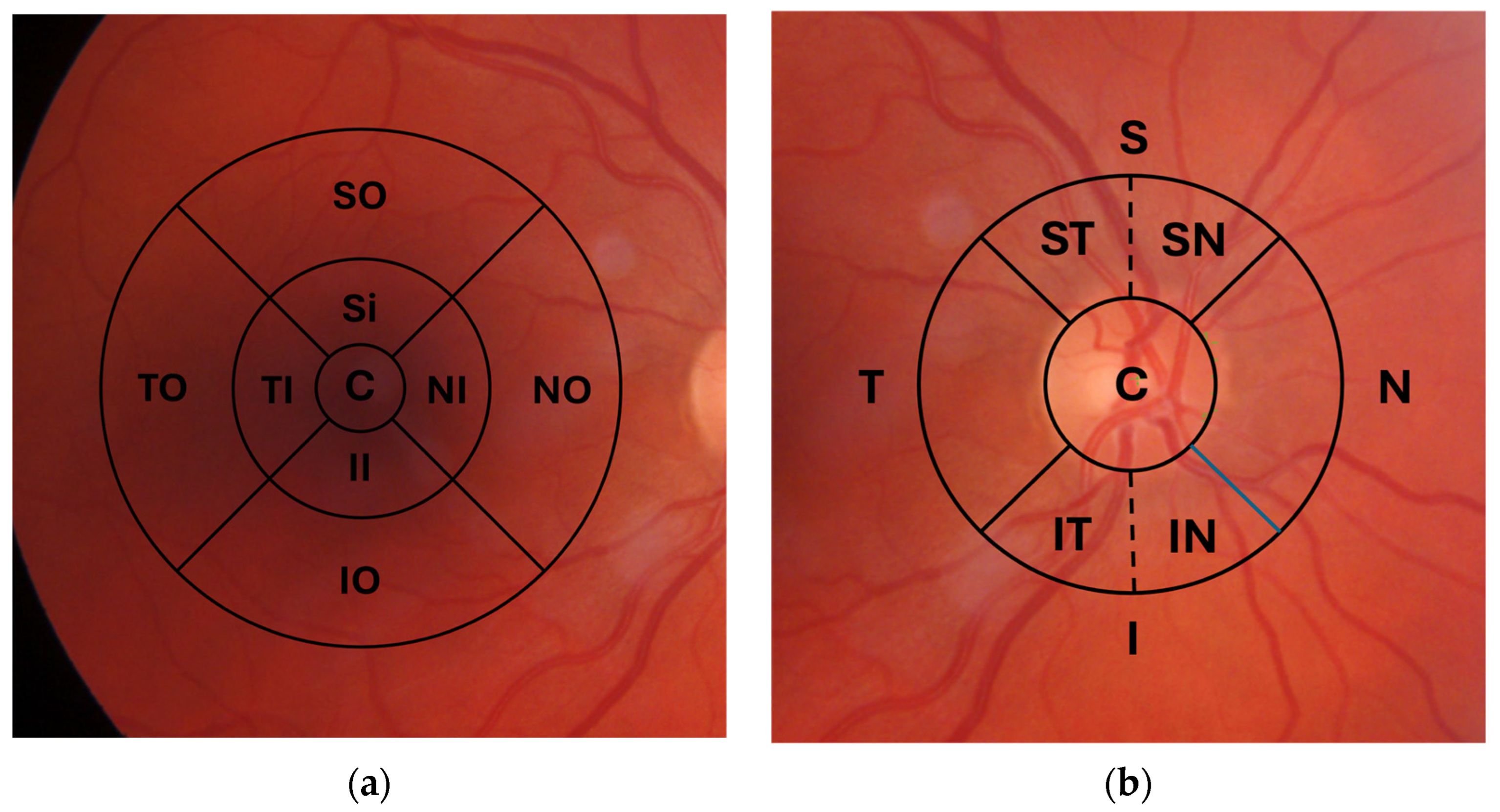

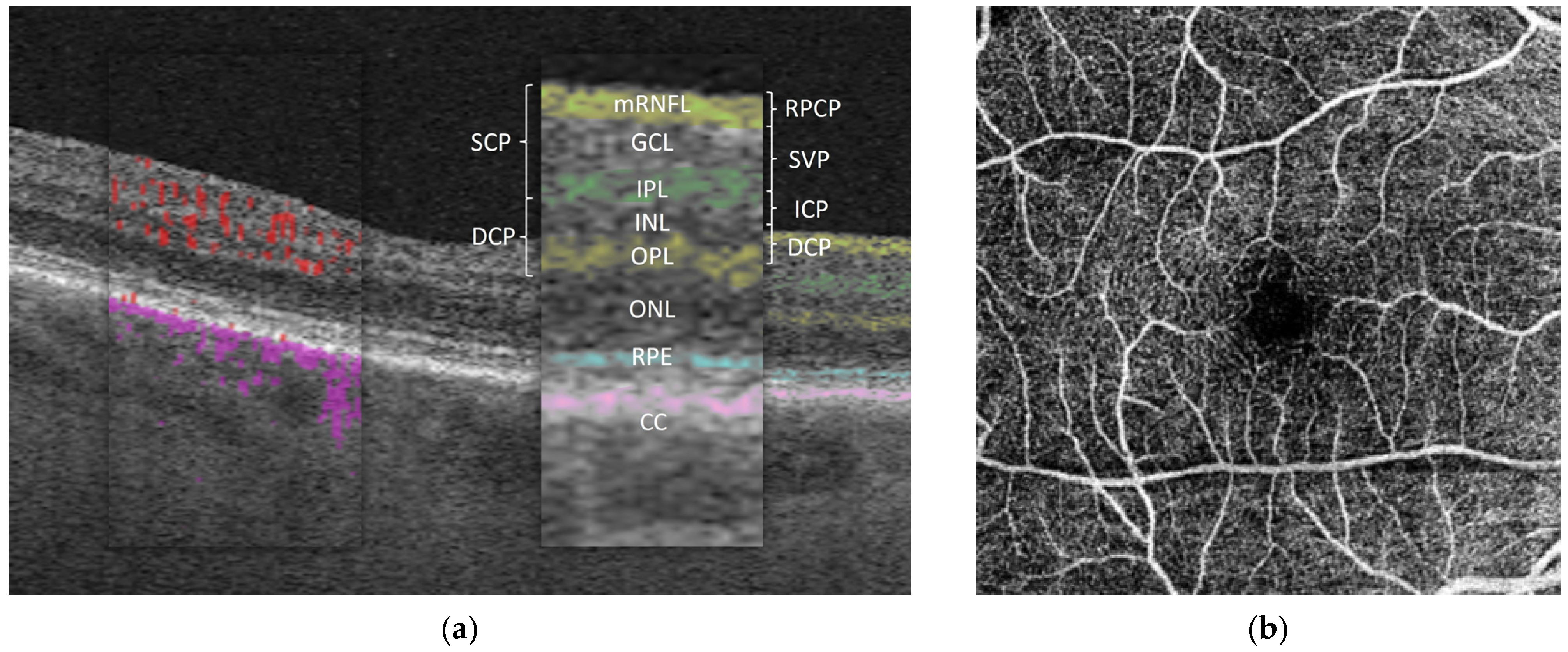

1. Introduction

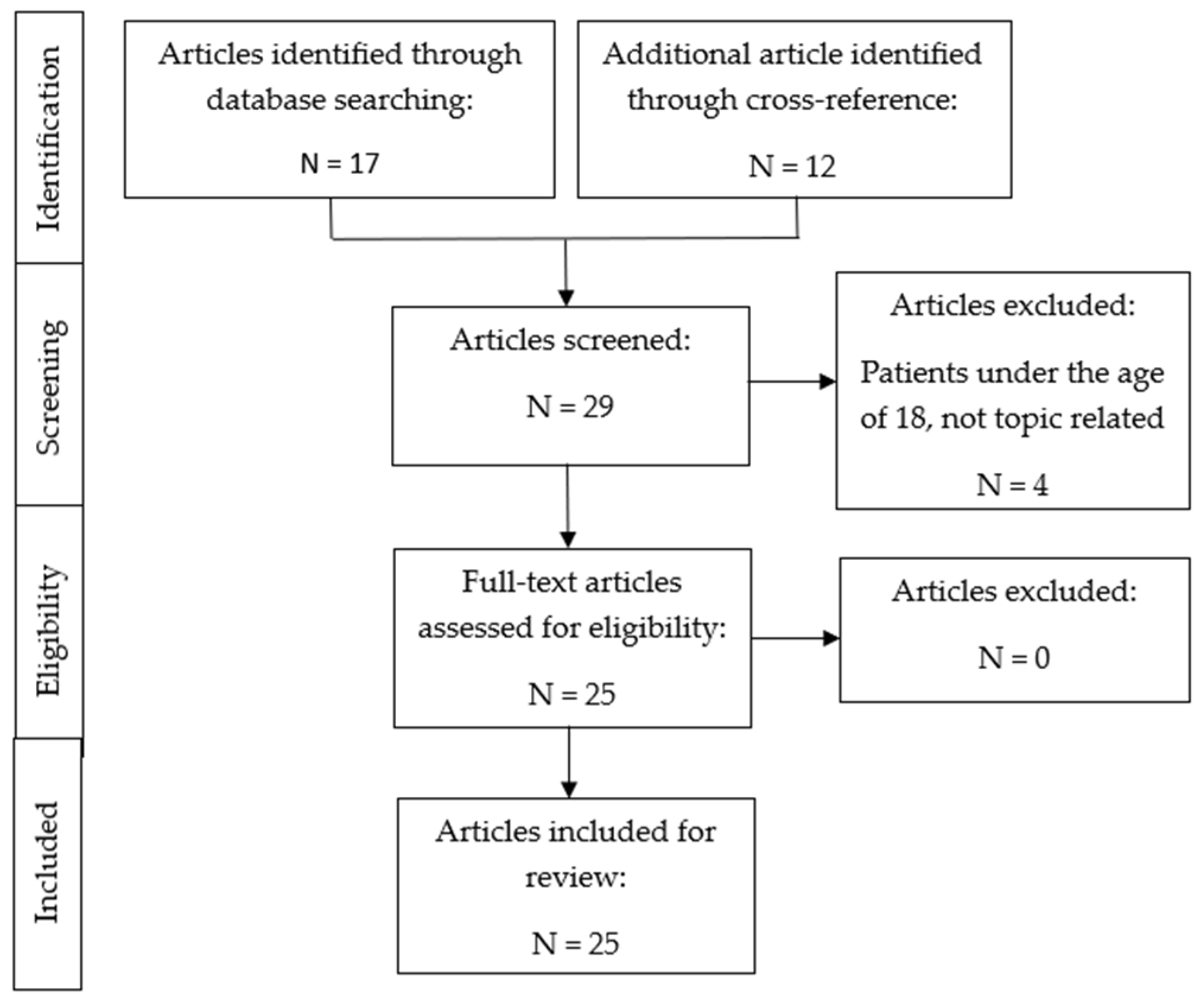

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. OCT (Table 1)

3.1.1. Long COVID Participants

3.1.2. Recovered COVID-19 Participants

3.1.3. Participants with an Acute COVID-19 Infection

| Publication | Device | Number of Participants | Time of Examination | Results: Significant Changes | Results: No Significant Changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long COVID Participants vs. Healthy Controls | |||||

| Kanra et al. [20] | Spectralis, Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany | 20 (34 eyes) 23 (39 eyes) | At least 4 weeks after completed treatment | mRNFL ↓ SI GCL ↓ SI, SO, IO, TO IPL ↓ SI, SO, TI, TO, NI | Remaining subregions pRNFL CMT |

| Dağ Şeker et al. [21] | SD-OCT Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany | 27 (54 eyes) 27 (54 eyes) | 31.18 ± 12.35 days after recovery | RT ↓ I, O mRNFL ↓ O GC-IPL ↓ I ONL ↓ C, I pRNFL ↓ C, NI | Remaining subregions INL OPL |

| 12 months later | mRNFL ↓O ONL ↓ I pRNFL ↓ C, IN | Remaining subregions GC-IPL INL OPL | |||

| None in longitudinal comparison | |||||

| Recovered COVID-19 participants vs. healthy controls | |||||

| Dipu et al. [30] | Spectral domain RS-3000 LITE, NIDEK Inc. | 35 (70 eyes) 12 (24 eyes) | 4 to 6 weeks after hospital discharge | GC-IPL ↓ | pRNFL mRNFL |

| Mavi Yildiz et al. [31] | Spectral domain, Spectralis (HRA + OCT) Heidelberg Engineering | 63 (119 eyes) 59 (117 eyes) | 2 to 8 weeks after positive real-time RT-PCR | pRNFL ↓ IT, ↑ S ONL ↑ CFT ↑ | Remaining subregions mRNFL GCL IPL INL OPL RPE |

| Savastano et al. [42] | Zeiss Cirrus 5000-HD-OCT Angioplex, Carl Zeiss, Meditec, Inc. | 80 ** 30 ** | 1 month from hospital discharge | None | mRNFL GCC CFT |

| Cennamo et al. [33] | Spectral domain-OCT AngioVue, Optovue Inc. | 40 (40 eyes) 40 (40 eyes) | 6 months after hospital discharge | ON RNFL ↓ | CFT |

| Szkodny et al. [34] | Swept Source OCT-DRI OCT Triton, Topcon Inc. | 78 (156 eyes) 49 (98 eyes) | 1 to 4 months after recovery | None | mRNFL ON |

| Burgos-Blasco et al. [24] | Spectralis Spectralis, Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany | 90 (90 eyes) 70 (70 eyes) | 4 weeks | pRNFL ↑ mRNFL↓ SI, NI, NO GCL ↑ SO, NO, IO 88 eyes, 70 eyes: ON RNFL↑ C, SN, IN | Remaining subregions |

| González-Zamora and Bilbao-Malavé et al. [39] | DRI OCT Triton SS-OCT Angio, Topcon Medical Systems Inc. | 25 (25 eyes) 25 (25 eyes) | 2 weeks after hospital discharge | GCL ↓ foceal, central ON RNFL ↑ | RT foveal, central RNFL foveal, central CT foveal, central |

| Bilbao-Malavé and González-Zamora et al. [27] | DRI OCT Triton SS-OCT Angio, Topcon Medical Systems Inc. | 17 (17 eyes) 17 (17 eyes) | 6 months after first examination | None | FT CCT ON RNFL |

| Abrishami et al. [44] | AngioVue system RTVue XR Avanti, Optovue, Fremont, CA, USA | 30 (15 eyes) 60 (30 eyes) | At least 2 weeks asymptomatic | None | pRNFL ONH |

| Follow-up vs. recovered COVID-19 participants | |||||

| Bilbao-Malavé and González-Zamora et al. [27] | DRI OCT Triton SS-OCT Angio, Topcon Medical Systems Inc. | 17 (33 eyes) 17 (33 eyes) | 6 months after first examination 2 weeks after hospital discharge | RNFL ↓ parafoveal GCL ↓ parafoveal ON RNFL ↓ FT ↑ | CCT |

| Acute COVID-19 infection vs. healthy control | |||||

| Jevnikar et al. [35] | SS-OCT, Topcon DRI OCT Triton; Topcon Corp., Tokyo, Japan | 75 (75 eyes) 101 (101 eyes) | 0 | Severe (n = 59): mRNFL ↑ S, I GCL ↑ TO Mild (n = 16): none | Severe (n = 59): Remaining subregions RT Mild (n = 16): mRNFL GCL RT |

| Koçkar et al. [40] | RTVue-100 OCT, Optovue Inc, Fremont, CA | 20 (40 eyes) 20 (40 eyes) | 0 | None | RNFL MT GCC |

| Acute COVID-19 infection vs. follow-up | |||||

| Jevnikar et al. [29] | SS-OCT, Topcon DRI OCT Triton; Topcon Corp., Tokyo, Japan | 30 (30 eyes) 30 (30 eyes) | 0 1 year after first examination | mRNFL ↓ II, IO, NO, SO | Remaining subregions |

| Acute COVID-19 infection vs. follow-up & healthy control | |||||

| Bayram et al. [25] | Spectral domain, Spectralis (HRA + OCT) Heidelberg Engineering Spectralis, Heidelberg, Germany | 53 (106 eyes) 53 (106 eyes) 53 (106 eyes) | 0 3 months after first examination | pRNFL ↑ OPL ↑ CT ↑ | mRNFL GCL IPL INL ONL ORL RPE CMT |

3.2. OCTA (Table 2)

3.2.1. Long COVID

3.2.2. Recovered COVID-19 Participants

3.2.3. Acute COVID-19 Infection

| Publication | Device | Number of Participants | Time of Examination | Results: Significant Changes | Results: No Significant Changes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long COVID Participants vs. Healthy or Recovered * Controls | |||||

| Szewczykowski and Mardin et al. [23] | Heidelberg Spectralis II, Heidelberg, Germany | 48 (92 eyes) 6 (9 eyes) | 200 ± 110 days (34-484 days) after confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection | VD SVP ↓ VD ICP ↓ VD DCP ↓ | none |

| Schlick and Lucio et al. [22] | Heidelberg Spectralis II, Heidelberg, Germany | 173 ** 28 ** | 231± 111 days of post-COVID-19 symptom persistency | VD ICP ↓ | VD SVP VD DCP |

| Recovered COVID-19 participants vs. healthy controls | |||||

| Dipu et al. [30] | Spectral domain RS-3000 LITE, NIDEK Inc. | 35 (70 eyes) 12 (24 eyes) | 4 to 6 weeks | VD SCP ↓ VD DCP ↓ FAZ ↑ | VD RPCP |

| Hazar et al. [26] | Optovue Angiovue, Optovue Inc. | 50 ** 55 ** | 1 month after hospital discharge | VD SCP ↓ parafoveal I, S VD DCP ↓ parafoveal S | FAZ |

| Cennamo et al. [33] | Optovue Angiovue, Optovue Inc. | 40 (40 eyes) 40 (40 eyes) | 6 months after hospital discharge | VD SCP ↓ VD DCP ↓ VD RPCP ↓ | FAZ |

| Szkodny et al. [34] | Swept Source OCT-DRI OCT Triton, Topcon Inc. | 78 (156 eyes) 49 (98 eyes) | 1 to 4 months after recovery | VD SCP ↓ | FAZ |

| Abrishami et al. [38] | Optovue Angiovue, Optovue Inc. | 31 (31 eyes) 23 (23 eyes) | ≥2 months after recovery | VD SCP ↓ foveal, parafoveal I VD DCP ↓ foveal FAZ ↑ | VD DCP parafoveal |

| Turker et al. [28] | Optovue Angiovue, Optovue Inc. | 25 (50 eyes) 25 (50 eyes) | 6 months after hospital discharge | VD SCP ↓ parafoveal VD DCP ↓ parafoveal S, I | VD SCP foveal VD DCP foveal FAZ |

| 25 (50 eyes 25 (50 eyes) | shortly after hospital discharge | VD SCP ↓ parafoveal VD DCP ↓ parafoveal | VD SCP foveal VD DCP foveal FAZ | ||

| González-Zamora and Bilbao-Malavé et al. [39] | DRI OCT Triton SS-OCT Angio, Topcon Medical Systems Inc. | 25 (25 eyes) 25 (25 eyes) | 2 weeks after hospital discharge | VD SCP ↓ foveal, parafoveal VD DCP ↓ foveal FAZ ↑ SCP | VD DCP parafoveal FAZ DCP, CC |

| Bilbao-Malavé and González-Zamora et al. [27] | DRI OCT Triton SS-OCT Angio, Topcon Medical Systems Inc. | 17 (17 eyes) 17 (17 eyes) | 6 months after first examination | VD SCP ↓ foveal FAZ ↑ superficial | VD SCP parafoveal VD DCP foveal, parafoveal |

| Kal et al. [36] | DRI-OCT Triton Topcon Inc., Tokyo, Japan | 63 (120 eyes) 43 (83 eyes) | 2 months after hospital discharge | none | VD RPCP VD ONH |

| Kal et al. [37] | Swept Source DRI-OCT Triton SS-OCT Angio, Topcon Inc., Tokyo, Japan | 49 (75 eyes) 43 (83 eyes) | 8 months after hospital discharge | VD SCP ↓ S, N, I, T VD DCP ↓ FAZ ↑ VD CC ↓ S, I, T | remaining subregions |

| Hohberger and Ganslmayer et al. [43] | Heidelberg Spectralis II, Heidelberg, Germany | 33 (33 eyes) 28 (28 eyes) | 34–281 days, 138.13 ± 70.67 days after positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test | VD ICP ↓ VD peripapillary ↓ | VD SVP VD DCP |

| Follow-up vs. recovered COVID-19 participants | |||||

| Turker et al. [28] | Optovue Angiovue, Optovue Inc. | 25 (50 eyes) 25 (50 eyes) | 6 months vs. shortly after recovery | VD SCP ↓ parafoveal VD DCP ↓ parafoveal | VD SCP foveal VD DCP foveal FAZ |

| Bilbao-Malavé and González-Zamora et al. [27] | DRI OCT Triton SS-OCT Angio, Topcon Medical Systems Inc. | 17 (33 eyes) 17 (33 eyes) | 6 months vs. 2 weeks after hospital discharge | FAZ ↑ superficial | VD SCP parafoveal, foveal VD DCP parafoveal, foveal |

| Abrishami et al. [41] | AngioVue system RTVue XR Avanti, Optovue, Fremont, CA, USA | 18 (36 eyes) 18 (36 eyes) | 1 month vs. shortly after recovery | VD DCP↓ mean, parafoveal, perifoveal | VD SCP FAZ |

| 3 months vs. shortly after recovery | VD SCP ↓ inferior hemifield, superior region, inferior region VD DCP ↓ mean, parafoveal, perifoveal | VD SCP FAZ | |||

| Kal et al. [37] | Swept Source DRI-OCT Triton SS-OCT Angio, Topcon Inc., Tokyo, Japan | 49 (75 eyes) 63 (120 eyes) | 8 months vs. 2 months after hospital discharge | VD SCP ↓ F, S, N, I VD DCP ↓ F, S, N, I VD CC ↓ S, N, I, T FAZ ↑ DCP | remaining subregions |

| Savastano et al. [32] | Zeiss Cirrus 5000-HD-OCT Angioplex, Carl Zeiss, Meditec, Inc. | 70 (70 eyes) 22 (22 eyes) | 1 month after hospital discharge and 2 months from symptom onset | none | VD SCP VD DCP FAZ |

| Acute COVID-19 infection vs. healthy control | |||||

| Jevnikar et al. [35] | SS-OCT, Topcon DRI OCT Triton; Topcon Corp., Tokyo, Japan | 75 (75 eyes) 101 (101 eyes) | 0 | none | VD SCP VD DCP FAZ |

| Acute COVID-19 infection vs. follow-up | |||||

| Jevnikar et al. [29] | Automated Retinal Image Analyser, Topcon Corp. | 30 (30 eyes) 30 (30 eyes) | 0 1 year after first examination | none | VD SCP parafoveal VD DCP parafoveal FAZ |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACE | angiotensin converting enzyme |

| ANG | angiotensin |

| BVCA | best corrected visual acuity |

| CFT | central foveal thickness |

| DCP | deep capillary plexus |

| FAZ | foveal avascular zone |

| GCL | ganglion cell layer |

| ICP | intermediate capillary plexus |

| INL | inner nuclear layer |

| IPL | inner plexiform layer |

| mRNFL | macular RNFL |

| OCT | optical coherence tomography |

| OCTA | optical coherence tomography angiography |

| ON | optic nerve |

| ONL | outer nuclear layer |

| OPL | outer plexiform layer |

| pRNFL | peripapillary RNFL |

| RNFL | retinal nerve fiber layer |

| RPCP | radial peripapillary capillary plexus |

| RPE | retinal pigment epithelium |

| SCP | superficial vascular plexus |

| SVP | superficial vascular plexus |

| VD | vessel density |

Appendix A

| Publication | Group | Systemic Exclusion Criteria | Ocular Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abrishami et al. [38] | COVID | diabetes mellitus, auto-immune disease, current pregnancy, breastfeeding, migraine | history of refractive or intraocular surgery, spherical refractive error > 5 D, cylindrical refractive error > 2 D, glaucoma, clinically apparent retinal disease, ocular media opacity preventing high-quality imaging or reduced OCTA scan quality |

| Control | / | / | |

| Abrishami et al. [41] | COVID | diabetes mellitus, glaucoma, migraine, breastfeeding, current pregnancy, clinically apparent retinal disease, auto-immune diseases, hospitalization, systemic corticosteroid treatment for COVID-19 | refractive or intraocular surgery, spherical refractive error > 5 D, cylindrical refractive error > 2 D, ocular media opacity preventing high-quality imaging or reduced OCTA scan quality |

| Control | / | / | |

| Abrishami et al. [44] | COVID | history of diabetes mellitus, systemic hypertension, dementia | history of intraocular surgery, glaucoma, ocular hypertension, macular disease |

| Control | history of diabetes mellitus, systemic hypertension, dementia | ocular or disc abnormalities, history of intraocular surgery, glaucoma, ocular hypertension, macular disease | |

| Bayram et al. [25] | COVID | any systemic diseases, signs and symptoms of COVID-19 or otherwise abnormal laboratory tests, including high acute phase reactants as systemic inflammatory markers | spherical equivalent > ±3 D, or >26 mm or <21 mm axial length, any ocular diseases, previous ocular surgery, ocular trauma |

| Control | / | / | |

| González-Zamora and Bilbao-Malavé et al. [39] | COVID | diabetes mellitus | cataract, vitreous hemorrhages, glaucoma, high myopia, fovea plana, AMD |

| Control | / | / | |

| Bilbao-Malavé and González-Zamora et al. [27] | COVID | diabetes mellitus | cataract, vitreous hemorrhages, glaucoma, high myopia, fovea plana, AMD |

| Control | / | / | |

| Burgos-Blasco et al. [24] | COVID | still presenting symptoms, on quarantine, unable to attend the hospital, concomitant psychiatric or neurological diseases | glaucoma, congenital optic nerve head abnormalities, myopia/hyperopia > ±6 D, macular disease, retinal vascular disorders, uveitis, and history of previous ophthalmic procedures other than cataract surgery and capsulotomy |

| Control | / | / | |

| Cennamo et al. [33] | COVID | history of stroke, blood disorders, diabetes, uncontrolled hypertension, neurodegenerative disease | congenital eye disease, myopia/hyperopia > ±6 D, retinal vascular diseases, macular diseases, previous ocular surgery except uneventful cataract surgery, history of other ocular disorders, significant lens opacity |

| Control | / | / | |

| Dağ Şeker et al. [21] | COVID | systemic diseases | ocular disease, history of ophthalmic surgery, systemic or topical drug administration, >±3 D spherical equivalent of refractive errors |

| Control | / | / | |

| Dipu et al. [30] | COVID | / | myopia/hyperopia > ±6 D, ocular congenital anomaly, macular disease, media opacity precluding OCTA |

| Control | systemic illness likely to influence the orbital vascular flow | / | |

| Hazar et al. [26] | COVID | severe COVID-19 requiring intensive care, diabetes, hypertension, rheumatic disease | glaucoma, retinal disease or eye trauma, media opacities affecting the imaging quality |

| Control | / | / | |

| Jevnikar et al. [29] | COVID | diabetes, arterial hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, history of stroke; concomitant infectious diseases: HIV, HSV, VZV, CMV; systemic treatment linked to retinal toxicity or smoking and other conditions that could have affected the retinal morphology | age-related macular degeneration and other retinal diseases, a history of glaucoma, myopia >−6 D |

| Jevnikar et al. [35] | COVID | diabetes, arterial hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, history of stroke; concomitant infectious diseases: HIV, HSV, VZV, CMV; systemic treatment linked to retinal toxicity or smoking and other conditions that could have affected the retinal morphology | age-related macular degeneration and other retinal diseases, a history of glaucoma, myopia >−6 D |

| Control | / | / | |

| Kal et al. [37] | COVID | diabetes mellitus | myopia/hyperopia > ±3 D, retinal vascular disease, macular and optic nerve disease, previous ocular surgery (including cataract or glaucoma surgery), uveitis, ocular trauma, AMD, other retinal degenerations and media opacity affecting the OCTA’s scan or image quality |

| Control | current or past COVID-19 symptoms, close contact with patients with COVID-19 within the 14 days before the examination | concomitant eye diseases | |

| Kal et al. [36] | COVID | diabetes mellitus, stroke, myocardial infarction, autoimmune diseases | myopia/hyperopia > ±3 D, central and peripheral retinal disorders, optic nerve disorders, a history of intraocular surgery, uveitis, ocular injury, opaque media affecting the quality of the OCT scan |

| Control | same as in COVID group, current or past COVID-19 symptoms, close contact with patients with COVID-19 within the 14 days before the examination | same as in COVID group, concomitant eye diseases | |

| Kanra et al. [20] | COVID | neurologic pathology | ocular pathology, myopia/hyperopia > ±3 D |

| Control | / | myopia/hyperopia > ±3 D | |

| Mavi Yildiz et al. [31] | COVID | pregnant or breastfeeding | diabetic retinopathy, other choroidal/retinal pathologies, high myopia (an axial length ≥ 26.5 mm), uveitis, glaucoma, previous optic neuropathy, history of intraocular surgery or laser treatment (except for phacoemulsification) |

| Control | interviewed potential signs and symptoms of COVID-19 and potentially exposed contacts within the 14 days before the examination | / | |

| Savastano et al. [32] | COVID | ongoing chemotherapy, drug abuse | myopia ≥ 6 D, choroidal atrophy, previously diagnosed glaucoma, retinal occlusive diseases, choroidal neovascularization, central serous chorioretinopathy, infectious choroiditis |

| Control | same as in COVID group | same as in COVID group | |

| Savastano et al. [42] | COVID | / | choroidal atrophy, high myopia, exudative AMD, previous episode of central serous chorioretinopathy, glaucoma, acquired and hereditary optic neuropathy, hereditary retinal diseases, demyelinating disorders, neurodegenerative disorders, and keratoconus |

| Control | / | same as in COVID group | |

| Schlick and Lucio et al. [22] | COVID | systemic disorders with retinal affection | local disorders with retinal affection |

| Control | / | / | |

| Szewczykowski and Mardin et al. [23] | COVID | systemic disorders with retinal affection | local disorders with retinal affection |

| Control | / | / | |

| Szkodny et al. [34] | COVID | history of symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection without a positive PCR test result, severe general conditions, including acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), myocarditis, cardiac arrhythmia, respiratory insufficiency, and kidney or multiple organ failure, unable to take part in the study | / |

| Control | / | ocular surface problems | |

| Turker et al. [28] | COVID | systemic disease that could affect retinal circulation, e.g., diabetes, hypertension, rheumatic diseases; systemic treatment with hydroxychloroquine or steroids | any ocular or systemic disease that could affect retinal circulation, intraocular pressure > 21 mmHg, axial length < 20 mm or > 24 mm, spherical refractive error > ±4 D, astigmatism > 1.5 D that may affect the OCTA results |

| Control | / | / | |

| Hohberger and Ganslmayer et al. [43] | COVID | / | no history of a previously known retinal or papillary disorder, no history of ocular laser therapy or surgery |

| Control | / | no history of ocular disorders or had a history of laser therapy or ocular surgery | |

| Koçkar et al. [40] | COVID | severe COVID-19, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic obstructive lung diseases, such as asthma, connective tissue disorders, autoimmune diseases | ocular surgery history, spherical equivalent > ±3 D, corneal astigmatism > ±3 D, cataract, corneal diseases, glaucoma, retinal vascular obstruction, AMD |

| Control | / | / |

Appendix B

References

- Koczulla, A.R. AWMF S1-Leitlinie Long/Post-COVID; Georg Thieme Verlag KG: Stuttgart, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, S.J.; Halim, A.; Halim, M.; Liu, S.; Aljeldah, M.; Al Shammari, B.R.; Alwarthan, S.; Alhajri, M.; Alawfi, A.; Alshengeti, A.; et al. Inflammatory and Vascular Biomarkers in Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of over 20 Biomarkers. Reviews in Medical Virology. 2023, Volume 33. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/rmv.2424 (accessed on 16 March 2023).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). COVID-19 Rapid Guideline: Managing the Long-Term Effects of COVID-19-PubMed [Internet]. 2022. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33555768/ (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Petersen, E.L.; Goßling, A.; Adam, G.; Aepfelbacher, M.; Behrendt, C.A.; Cavus, E.; Blankenberg, S. Multi-organ assessment in mainly non-hospitalized individuals after SARS-CoV-2 infection: The Hamburg City Health Study COVID programme. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 1124–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceban, F.; Ling, S.; Lui, L.M.; Lee, Y.; Gill, H.; Teopiz, K.M.; Rodrigues, N.B.; Subramaniapillai, M.; Di Vincenzo, J.D.; Cao, B.; et al. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2022, 101, 93–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiyegbusi, O.L.; E Hughes, S.; Turner, G.; Rivera, S.C.; McMullan, C.; Chandan, J.S.; Haroon, S.; Price, G.; Davies, E.H.; Nirantharakumar, K.; et al. Symptoms, complications and management of long COVID: A review. J. R. Soc. Med. 2021, 114, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Haupert, S.R.; Zimmermann, L.; Shi, X.; Fritsche, L.G.; Mukherjee, B. Global Prevalence of Post-Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Condition or Long COVID: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 226, 1593–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkodaymi, M.S.; Omrani, O.A.; Fawzy, N.A.; Shaar, B.A.; Almamlouk, R.; Riaz, M.; Obeidat, M.; Obeidat, Y.; Gerberi, D.; Taha, R.M.; et al. Prevalence of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome symptoms at different follow-up periods: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 657–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raveendran, A.V.; Jayadevan, R.; Sashidharan, S. Long COVID: An overview. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2021, 15, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchler, T.; Günthner, R.; Ribeiro, A.; Hausinger, R.; Streese, L.; Wöhnl, A.; Kesseler, V.; Negele, J.; Assali, T.; Carbajo-Lozoya, J.; et al. Persistent endothelial dysfunction in post-COVID-19 syndrome and its associations with symptom severity and chronic inflammation. Angiogenesis 2023, 26, 547–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovas, A.; Osiaevi, I.; Buscher, K.; Sackarnd, J.; Tepasse, P.-R.; Fobker, M.; Kühn, J.; Braune, S.; Göbel, U.; Thölking, G.; et al. Microvascular dysfunction in COVID-19: The MYSTIC study. Angiogenesis 2021, 24, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smadja, D.M.; Mentzer, S.J.; Fontenay, M.; Laffan, M.A.; Ackermann, M.; Helms, J.; Jonigk, D.; Chocron, R.; Pier, G.B.; Gendron, N.; et al. COVID-19 is a systemic vascular hemopathy: Insight for mechanistic and clinical aspects. Angiogenesis 2021, 24, 755–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podoleanu, A.G.H. Optical coherence tomography. J. Microsc. 2012, 247, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Invernizzi, A.; Cozzi, M.; Staurenghi, G. Optical coherence tomography and optical coherence tomography angiography in uveitis: A review. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2019, 47, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupidi, M.; Cerquaglia, A.; Chhablani, J.; Fiore, T.; Singh, S.R.; Piccolino, F.C.; Corbucci, R.; Coscas, F.; Coscas, G.; Cagini, C. Optical coherence tomography angiography in age-related macular degeneration: The game changer. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 28, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaide, R.F.; Fujimoto, J.G.; Waheed, N.K.; Sadda, S.R.; Staurenghi, G. Optical coherence tomography angiography. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2018, 64, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, S.H.; Sharma, T. Fluorescein Angiography. In Atlas of Inherited Retinal Diseases; Tsang, S.H., Sharma, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2018; Volume 1085, pp. 7–10. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-95046-4_2 (accessed on 9 May 2023).

- Invernizzi, A.; Pellegrini, M.; Cornish, E.P.; Teo, K.M.Y.C.; Cereda, M.; Chabblani, J. Imaging the Choroid: From Indocyanine Green Angiography to Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. Asia-Pac. J. Ophthalmol. 2020, 9, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J.P.; Zhang, M.; Hwang, T.S.; Bailey, S.T.; Wilson, D.J.; Jia, Y.; Huang, D. Detailed Vascular Anatomy of the Human Retina by Projection-Resolved Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanra, A.Y.; Altınel, M.G.; Alparslan, F. Evaluation of retinal and choroidal parameters as neurodegeneration biomarkers in patients with post-covid-19 syndrome. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2022, 40, 103108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dağ Şeker, E.; Erbahçeci Timur, İ.E. Assessment of early and long-COVID related retinal neurodegeneration with optical coherence tomography. Int. Ophthalmol. 2022, 43, 2073–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlick, S.; Lucio, M.; Wallukat, G.; Bartsch, A.; Skornia, A.; Hoffmanns, J.; Szewczykowski, C.; Schröder, T.; Raith, F.; Rogge, L.; et al. Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: Retinal Microcirculation as a Potential Marker for Chronic Fatigue. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczykowski, C.; Mardin, C.; Lucio, M.; Wallukat, G.; Hoffmanns, J.; Schröder, T.; Raith, F.; Rogge, L.; Heltmann, F.; Moritz, M.; et al. Long COVID: Association of Functional Autoantibodies against G-Protein-Coupled Receptors with an Impaired Retinal Microcirculation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos-Blasco, B.; Güemes-Villahoz, N.; Vidal-Villegas, B.; Martinez-De-La-Casa, J.M.; Donate-Lopez, J.; Martín-Sánchez, F.J.; González-Armengol, J.J.; Porta-Etessam, J.; Martin, J.L.R.; Garcia-Feijoo, J. Optic nerve and macular optical coherence tomography in recovered COVID-19 patients. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 32, 628–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, N.; Gundogan, M.; Ozsaygılı, C.; Adelman, R.A. Posterior ocular structural and vascular alterations in severe COVID-19 patients. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2022, 260, 993–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazar, L.; Karahan, M.; Vural, E.; Ava, S.; Erdem, S.; Dursun, M.E.; Keklikçi, U. Macular vessel density in patients recovered from COVID 19. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2021, 34, 102267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilbao-Malavé, V.; González-Zamora, J.; de Viteri, M.S.; de la Puente, M.; Gándara, E.; Casablanca-Piñera, A.; Boquera-Ventosa, C.; Zarranz-Ventura, J.; Landecho, M.F.; García-Layana, A. Persistent Retinal Microvascular Impairment in COVID-19 Bilateral Pneumonia at 6-Months Follow-Up Assessed by Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, I.C.; Dogan, C.U.; Dirim, A.B.; Guven, D.; Kutucu, O.K. Evaluation of early and late COVID-19-induced vascular changes with OCTA. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 57, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jevnikar, K.; Meglič, A.; Lapajne, L.; Logar, M.; Valentinčič, N.V.; Petrovič, M.G.; Mekjavić, P.J. The Comparison of Retinal Microvascular Findings in Acute COVID-19 and 1-Year after Hospital Discharge Assessed with Multimodal Imaging—A Prospective Longitudinal Cohort Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dipu, T.; Goel, R.; Arora, R.; Thakar, M.; Gautam, A.; Shah, S.; Gupta, Y.; Chhabra, M.; Kumar, S.; Singh, K.; et al. Ocular sequelae in severe COVID-19 recovered patients of second wave. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 70, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, A.M.; Gunduz, G.U.; Yalcinbayir, O.; Ozturk, N.A.A.; Avci, R.; Coskun, F. SD-OCT assessment of macular and optic nerve alterations in patients recovered from COVID-19. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 57, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savastano, M.C.; Gambini, G.; Cozzupoli, G.M.; Crincoli, E.; Savastano, A.; De Vico, U.; Culiersi, C.; Falsini, B.; Martelli, F.; Minnella, A.M.; et al. Retinal capillary involvement in early post-COVID-19 patients: A healthy controlled study. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2021, 259, 2157–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cennamo, G.; Reibaldi, M.; Montorio, D.; D’Andrea, L.; Fallico, M.; Triassi, M. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Features in Post-COVID-19 Pneumonia Patients: A Pilot Study. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 227, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkodny, D.; Wylęgała, E.; Sujka-Franczak, P.; Chlasta-Twardzik, E.; Fiolka, R.; Tomczyk, T.; Wylęgała, A. Retinal OCT Findings in Patients after COVID Infection. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jevnikar, K.; Meglič, A.; Lapajne, L.; Logar, M.; Valentinčič, N.V.; Petrovič, M.G.; Mekjavić, P.J. The impact of acute COVID-19 on the retinal microvasculature assessed with multimodal imaging. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2023, 261, 1115–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kal, M.; Brzdęk, M.; Zarębska-Michaluk, D.; Pinna, A.; Mackiewicz, J.; Odrobina, D.; Winiarczyk, M.; Karska-Basta, I. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Assessment of the Optic Nerve Head in Patients Hospitalized Due to COVID-19 Bilateral Pneumonia. Medicina 2024, 60, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kal, M.; Winiarczyk, M.; Zarębska-Michaluk, D.; Odrobina, D.; Cieśla, E.; Płatkowska-Adamska, B.; Mackiewicz, J. Long-Term Effect of SARS-CoV-2 Infection on the Retinal and Choroidal Microvasculature. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrishami, M.; Emamverdian, Z.; Shoeibi, N.; Omidtabrizi, A.; Daneshvar, R.; Rezvani, T.S.; Saeedian, N.; Eslami, S.; Mazloumi, M.; Sadda, S.; et al. Optical coherence tomography angiography analysis of the retina in patients recovered from COVID-19: A case-control study. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 56, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Zamora, J.; Bilbao-Malavé, V.; Gándara, E.; Casablanca-Piñera, A.; Boquera-Ventosa, C.; Landecho, M.F.; Zarranz-Ventura, J.; García-Layana, A. Retinal Microvascular Impairment in COVID-19 Bilateral Pneumonia Assessed by Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koçkar, A.; Yilmaz, H.; Sezign, B.İ.; Yüzbaşioğlu, E. Posterior segment optical coherence tomography findings in patients with COVID-19. Hitit Med. J. 2023, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrishami, M.; Hassanpour, K.; Hosseini, S.; Emamverdian, Z.; Ansari-Astaneh, M.-R.; Zamani, G.; Gharib, B.; Abrishami, M. Macular vessel density reduction in patients recovered from COVID-19: A longitudinal optical coherence tomography angiography study. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2022, 260, 771–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savastano, A.; Crincoli, E.; Savastano, M.C.; Younis, S.; Gambini, G.; De Vico, U.; Cozzupoli, G.M.; Culiersi, C.; Rizzo, S. Peripapillary Retinal Vascular Involvement in Early Post-COVID-19 Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohberger, B.; Ganslmayer, M.; Lucio, M.; Kruse, F.; Hoffmanns, J.; Moritz, M.; Rogge, L.; Heltmann, F.; Szewczykowski, C.; Fürst, J.; et al. Retinal Microcirculation as a Correlate of a Systemic Capillary Impairment After Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 676554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrishami, M.; Daneshvar, R.; Emamverdian, Z.; Tohidinezhad, F.; Eslami, S. Optic Nerve Head Parameters and Peripapillary Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness in Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2022, 30, 1035–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, M.L.; Mojana, F.; Bartsch, D.-U.; Freeman, W.R. Imaging of Long-term Retinal Damage after Resolved Cotton Wool Spots. Ophthalmology 2009, 116, 2407–2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, V.T.; Sun, Z.; Tang, S.; Chen, L.J.; Wong, A.; Tham, C.C.; Wong, T.Y.; Chen, C.; Ikram, M.K.; Whitson, H.E.; et al. Spectral-Domain OCT Measurements in Alzheimer’s Disease. Ophthalmology 2019, 126, 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britze, J.; Pihl-Jensen, G.; Frederiksen, J.L. Retinal ganglion cell analysis in multiple sclerosis and optic neuritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. 2017, 264, 1837–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suciu, C.I.; Suciu, V.I.; Nicoara, S.D. Optical Coherence Tomography (Angiography) Biomarkers in the Assessment and Monitoring of Diabetic Macular Edema. J. Diabetes Res. 2020, 2020, 6655021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, H.L.; Pradhan, Z.S.; Suh, M.H.; Moghimi, S.; Mansouri, K.; Weinreb, R.N. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography in Glaucoma. J. Glaucoma 2020, 29, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziedziak, J.; Zaleska-Żmijewska, A.; Szaflik, J.P.; Cudnoch-Jędrzejewska, A. Impact of Arterial Hypertension on the Eye: A Review of the Pathogenesis, Diagnostic Methods, and Treatment of Hypertensive Retinopathy. Med. Sci. Monit. 2022, 28, e935135-1. Available online: https://www.medscimonit.com/abstract/index/idArt/935135 (accessed on 14 November 2023). [CrossRef]

- Aboud, S.A.-A.; Hammouda, L.M.; Saif, M.Y.S.; Ahmed, S.S. Effect of smoking on the macula and optic nerve integrity using optical coherence tomography angiography. Eur. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 32, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaymaz, A.; Ulaş, F.; Toprak, G.; Uyar, E.; Çelebi, S. Evaluation of the acute effects of cigarette smoking on the eye of non-Smoking healthy young male subjects by optical coherence tomography angiography. Cutan. Ocul. Toxicol. 2020, 39, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institutes of Health (NIH). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines. J. Med. Virol. 2023, 92, 1484–1490. [Google Scholar]

- Beacon, T.H.; Delcuve, G.P.; Davie, J.R. Epigenetic regulation of ACE2, the receptor of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Genome 2021, 64, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Shen, Y.M.; Jiang, M.N.; Lou, X.F.; Shen, Y. Ocular Blood Flow Autoregulation Mechanisms and Methods. J. Ophthalmol. 2015, 2015, 864871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palkovits, S.; Fuchsjäger-Mayrl, G.; Kautzky-Willer, A.; Richter-Müksch, S.; Prinz, A.; Vécsei-Marlovits, V.; Garhöfer, G.; Schmetterer, L. Retinal white blood cell flux and systemic blood pressure in patients with type 1 diabetes. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2013, 251, 1475–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Chou, Y.; Zhao, X.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y. Early Detection of Microvascular Impairments with Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography in Diabetic Patients Without Clinical Retinopathy: A Meta-analysis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 222, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.A.; Soares, L.C.M.; Nascimento, P.A.; Cirillo, L.R.N.; Sakuma, H.T.; da Veiga, G.L.; Fonseca, F.L.A.; Lima, V.L.; Abucham-Neto, J.Z. Retinal findings in hospitalised patients with severe COVID-19. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 106, 102–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinho, P.M.; Marcos, A.A.A.; Romano, A.C.; Nascimento, H.; Belfort, R. Retinal findings in patients with COVID-19. Lancet 2020, 395, 1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Invernizzi, A.; Torre, A.; Parrulli, S.; Zicarelli, F.; Schiuma, M.; Colombo, V.; Giacomelli, A.; Cigada, M.; Milazzo, L.; Ridolfo, A.; et al. Retinal findings in patients with COVID-19: Results from the SERPICO-19 study. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 27, 100550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landecho, M.F.; Yuste, J.R.; Gándara, E.; Sunsundegui, P.; Quiroga, J.; Alcaide, A.B.; García-Layana, A. COVID-19 retinal microangiopathy as an in vivo biomarker of systemic vascular disease? J. Intern. Med. 2021, 289, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greig, E.C.; Duker, J.S.; Waheed, N.K. A practical guide to optical coherence tomography angiography interpretation. Int. J. Retin. Vitr. 2020, 6, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jerratsch, H.; Beuse, A.; Spitzer, M.S.; Grohmann, C. The Current Status of OCT and OCTA Imaging for the Diagnosis of Long COVID. J. Clin. Transl. Ophthalmol. 2024, 2, 113-130. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcto2040010

Jerratsch H, Beuse A, Spitzer MS, Grohmann C. The Current Status of OCT and OCTA Imaging for the Diagnosis of Long COVID. Journal of Clinical & Translational Ophthalmology. 2024; 2(4):113-130. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcto2040010

Chicago/Turabian StyleJerratsch, Helen, Ansgar Beuse, Martin S. Spitzer, and Carsten Grohmann. 2024. "The Current Status of OCT and OCTA Imaging for the Diagnosis of Long COVID" Journal of Clinical & Translational Ophthalmology 2, no. 4: 113-130. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcto2040010

APA StyleJerratsch, H., Beuse, A., Spitzer, M. S., & Grohmann, C. (2024). The Current Status of OCT and OCTA Imaging for the Diagnosis of Long COVID. Journal of Clinical & Translational Ophthalmology, 2(4), 113-130. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcto2040010