Abstract

Research demonstrates that overcoming school violence is crucial for ensuring a safe environment and quality education for all students. The scientific literature shows that educators can significantly impact school violence, but their effectiveness hinges on the quality of their training. Therefore, identifying the most effective training types is essential. This literature review aims to identify and synthesize the characteristics of teacher-training programs that have effectively reduced school violence. Inclusion criteria were studies focusing on interventions to reduce school violence, with either quantitative or qualitative outcomes. Exclusion criteria were studies not specifically addressing school violence or lacking evaluative measures. Data sources included Web of Science, EBSCO Host, Medline, Scielo, and Scopus, with searches conducted in December 2023. From an initial pool of 2128 articles, 13 studies were included. The results, synthesized through narrative analysis, reveal the key features of teacher-training programs that effectively address school violence, including the nature of the training, the content covered, and the social impact achieved.

1. Introduction

Creating inclusive, safe, and violence-free environments for child development is a global priority in achieving quality education. This is explicitly emphasized as a key objective in Sustainable Development Goal 4 [1]. However, this goal remains challenging due to the pervasive issue of school violence [2]. School violence is a pervasive issue that transcends regional and national boundaries. Estimates indicate that one in three students experience bullying on a monthly basis worldwide [3]. Research has shown that over 1 billion children aged 2 to 17 experienced some form of violence in the past year alone [4]. In industrialized countries, 17 million adolescents admitted to bullying their peers at school [5]. For example, 19.4% of young people in the United States reported engaging in bullying behaviors [6], while 27% of adolescents in Australia and Brazil, as well as 28% in the United States, reported being victims of bullying [7]. This highlights the widespread nature of violence against children, a global issue that affects millions across various regions [8].

School violence can take various forms, such as physical and verbal abuse, as well as social and relational exclusion and humiliation [9]. It also includes peer violence among students, as well as violence between students and teachers in both directions [10,11,12]. This violence negatively impacts academic performance, physical health, and the socio-emotional well-being of millions of children worldwide [2]. Research shows that children who experience school violence often have poorer academic outcomes [13,14]. These children are more likely to feel marginalized, miss classes, and experience anxiety related to exams [15]. Additionally, the scientific literature indicates that school violence impacts various aspects of health. Those affected are significantly more likely to suffer from post-traumatic stress, anxiety, depression, digestive issues, self-harm, suicidal ideation, or even suicide [16,17,18]. Furthermore, toxic stress can also affect brain activity and structure [19] and may alter the epigenome [20].

Any student can be a victim of bullying, but those from more vulnerable groups are at a higher risk [21]. Addressing school violence is essential for creating inclusive educational environments. Obstacles like bullying and intentional social exclusion pose significant challenges to inclusive education [22], with the most vulnerable students suffering the most. For instance, students from low socio-economic backgrounds face increased bullying rates [23], and immigrant students are also more likely to be bullied [24]. Additionally, students in special education are more often victims and perpetrators of bullying compared to their peers [25], and those with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) experience higher levels of bullying [26]. LGBTQ youth also face bullying at higher rates, significantly impacting their mental and physical health [27]. Thus, eradicating all forms of school violence is crucial to making schools more inclusive by removing the barriers that vulnerable students encounter in achieving academic and social success.

Research has shown that teachers can be key to overcoming school violence [28,29]. However, the scientific literature reflects that teacher interventions are not always successful. Despite teachers’ efforts to reduce bullying, students often do not view them as competent in recognizing or resolving incidents [30]. In one study, for example, of 400 students, only 10% expressed confidence in their school’s ability to handle relational bullying [31].

Additionally, the scientific literature shows that teachers sometimes do not act. Teachers are more likely to intervene in cases of physical violence compared to verbal or relational aggression [32]. Additionally, lack of awareness about the prevalence of violence [33], insufficient ability to identify school violence [34], and insufficient empathy for victims [35] can discourage teachers from intervening. Furthermore, teachers might refrain from intervening if they perceive violent behaviors as normal among children [36], view them as mere teasing [37], or believe non-physical violence does not require attention [38].

Research also shows that teachers sometimes fail to act because they believe they cannot achieve any improvement [39,40]. When students perceive teachers as ineffective, school violence increases notably [41]. Failure to intervene can exacerbate bullying [42]. Therefore, it is crucial to identify interventions that promote teacher participation in overcoming school violence.

Effective teacher training has been shown to help teachers address school violence more successfully [43]. In fact, the scientific literature demonstrates that such training is key to enabling teachers to decisively contribute to overcoming school violence [44,45,46]. Furthermore, results from a systematic review [47] indicate that effective teacher-training programs designed to address school violence have core components that can be applied across different countries and cultures. In addition, these programs have the potential to extend beyond school settings, thus influencing community attitudes and approaches toward violence. Another systematic review shows that teachers who participate in effective training programs transition from feeling uninformed, isolated, and powerless to act to perceiving that they share challenges with other teachers. They become able to engage in group discussions, share reflections, and learn how to respond effectively to the challenges they face in school [48]. Therefore, it is essential to identify the types of training that properly prepare teachers, as not all training types equip them to tackle the challenges they face in schools [49].

This study aims to address this issue by identifying school-based interventions with social impact. The European Commission uses the concept of social impact to define improvements in people’s lives resulting from the implementation of scientific research [50]. This research contributes to overcoming school violence by analyzing studies that report on teacher trainings that led to improvements in addressing school violence. More specifically, the objectives of this literature review are to identify (1) the types of training designed to equip teachers to effectively address school violence, including reference materials, training formats, participant types, and duration; (2) the content covered in the training; and (3) the social impact achieved by the analyzed teacher-training programs in terms of reducing violence, improving school climate, and promoting inclusive and egalitarian quality relationships.

To contribute in this way, the present literature review aims to answer the following research questions:

- (1)

- What types of teacher training have been identified by research as having social impact on addressing school violence?

- (2)

- What content has research identified within teacher training that promotes social impact in addressing school violence?

- (3)

- What social impact have the identified studies demonstrated in terms of addressing school violence?

2. Methods

This study is a systematic review conducted following PRISMA Statement guidelines [51] that synthesizes the existing scientific knowledge referring to teacher training with social impact. The goal was to minimize bias by identifying, assessing, and synthesizing all relevant studies on this specific subject. For this study, the CHIP framework was used, which is employed to structure qualitative research questions in psychology. CHIP stands for Context, How, Issues, and Population. In this case, the context is “School”, the “How” refers to “Teacher Training with Social Impact”, the issue is “overcoming school violence”, and the population is “teachers”. Thus, the research question for this study is the following: in the context of schools, how does teacher training achieving social impact assist teachers in overcoming school violence?

2.1. Search Strategy

In conducting this literature review, we ensured a high level of consistency and thoroughness throughout the process. We systematically defined and applied inclusion and exclusion criteria, ensuring that only studies meeting our rigorous standards were considered. The searches for this systematic review were conducted over a two-day period, from 30 November to 1 December 2023, across five major global databases. These databases included Web of Science (WoS) and WoS Core Collection, EBSCO Host, Medline, Scielo, and Scopus. The searches were performed exclusively in English to ensure consistency and comprehensiveness in the review process. The eligibility criteria for inclusion in the review encompassed journal articles, reports, books, and book chapters that had been published within the last decade, specifically from 2013 to 2023. This time frame was selected to ensure that the review incorporated the most recent and relevant studies, reflecting the latest advancements and insights in the field. The comprehensive search strategy was designed to capture a wide range of literature to provide a thorough synthesis of the existing scientific knowledge on teacher-training programs on school violence prevention with social impact.

Search terms and keywords were meticulously developed and tailored for each database (see Table 1) following the CHIP framework. This procedure was essential for retrieving all pertinent information related to the review questions. Once the search terms were established, searches were systematically executed within each chosen database. This phase strictly adhered to the specific parameters and search functionalities inherent to each database, thereby optimizing the effectiveness and comprehensiveness of the retrieval process.

Table 1.

Search terms.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria covered systematic reviews and research studies employing qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods published within the last 10 years, from 2013 to 2023. The selected studies focused on teacher training with a proven social impact aimed at addressing all forms of school violence, meaning that only those studies demonstrating improvements in school violence through teacher training were included. In response to the research questions, the review specifically included studies that detailed the type of training used, the content covered, and the impacts achieved.

Exclusion criteria included studies focused on pre-service teachers and those unrelated to school violence. Additionally, studies that did not demonstrate social impact—meaning those that did not show improvements in school violence through teacher training—were excluded. Studies that did not provide details on the characteristics of the implemented teacher training were also excluded, as they did not align with the objectives of this literature review. Articles not published in English were excluded as well.

2.3. Screening

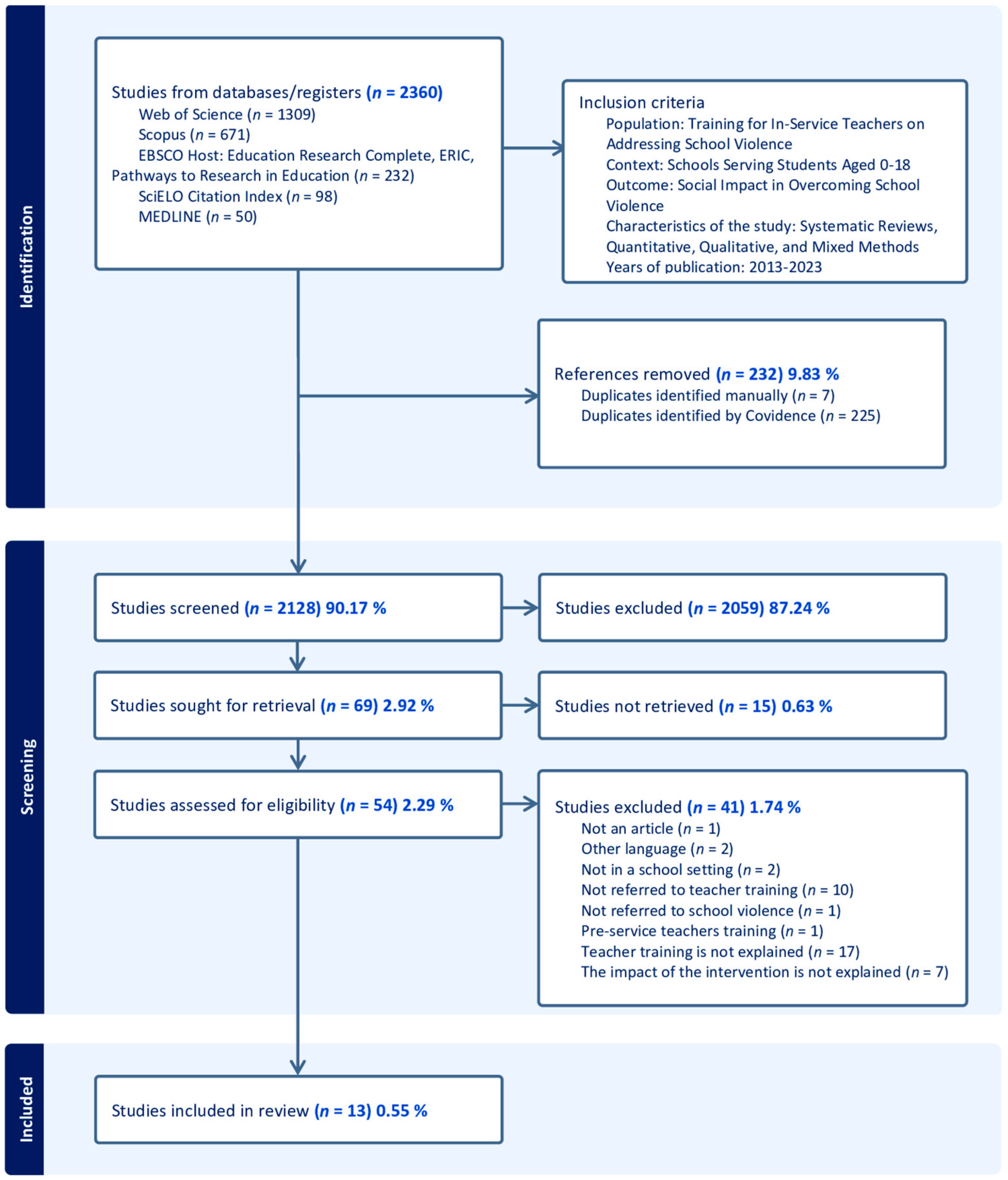

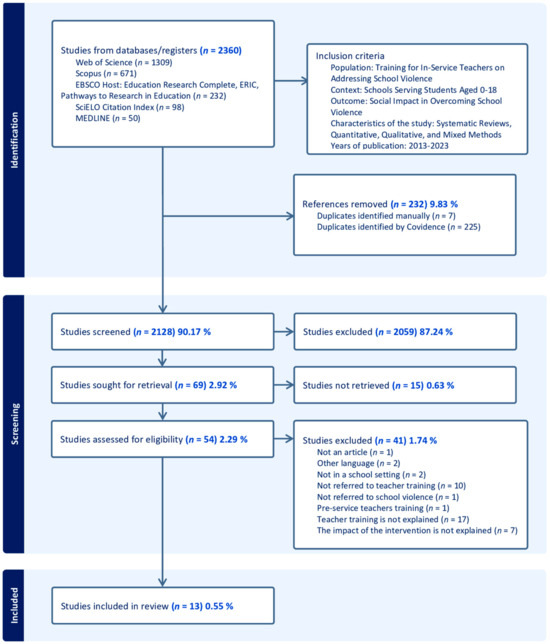

The screening process was managed using Covidence, a tool designed for systematic review management, which also generated a PRISMA flow diagram (see Figure 1). A total of 2360 studies were imported for screening, sourced from various databases. The majority were from Web of Science (1309 studies) and Scopus (671 studies), with additional contributions from EBSCO Host, including Education Research Complete, ERIC, and Pathways to Research in Education (232 studies, 9.83%). Other sources included the SciELO Citation Index (98 studies) and MEDLINE (50 studies). The tool then automatically removed 225 duplicates, and 7 were removed manually. In the first phase, a total of 2128 studies were screened (90.17%), and, of these, 2059 (87.24%) were deemed irrelevant based on the established criteria.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram.

A total of 54 (2.29%) full-text studies were sought for retrieval and assessed for eligibility in the second screening phase. Out of these, 41 (1.74%) studies were excluded based on various criteria: 17 studies did not explain teacher training, 10 studies did not include any training for teachers, 2 studies were not conducted in a school setting, 2 studies were published in languages other than the specified criteria, 1 study did not address school violence, 1 study focused on pre-service teacher training, 1 study did not meet the criteria of being an article, and 2 studies did not explain the social impact of the intervention.

The flow diagram created with the tool Covidence represents all of the screening process (see Figure 1).

2.4. Data Extraction

Data from the 13 (0.55%) included studies were extracted following a thematic analysis, beginning with familiarization with the collected literature and involving multiple readings to gain an overall understanding of the content. Initial codes were then generated to organize key concepts and findings from the literature. These codes were grouped into broader themes, which were reviewed and refined to ensure they accurately represented the literature. Each theme was clearly defined and named, followed by a detailed report that included illustrative excerpts from the reviewed studies. Throughout the process, measures were taken to ensure reliability and validity, such as independent coding and triangulation, culminating in a well-structured presentation of the themes, discussion, and conclusions. To do so, an Excel sheet was used to organize and categorize all of the information obtained from the included studies. The studies considered for inclusion in this review provided data across three key dimensions: type of teacher training, content of the teacher training, and the social impact achieved by the included studies.

The first dimension refers to the type of teacher training, which includes the various forms and methodologies of teacher-training programs. It also considers the format of the training, such as workshops, seminars, online courses, or hands-on classroom experiences, as well as the duration and intensity of the training programs. Additionally, it takes into account the qualifications and background of the trainers.

The second dimension includes the content of the teacher training. This dimension examines the specific topics and skills covered in the teacher-training programs. It includes the curriculum and educational materials used, the pedagogical strategies taught, and the focus areas, such as violence-prevention approaches, classroom management, bystander intervention, conflict-solving, intervention skills, or any other strategy to overcome school violence.

The third dimension focuses on the social impact achieved, which assesses the broader outcomes and effects of the teacher-training programs on the school. Specifically, it looks at the reduction of school violence, the enhancement of the school climate, and the promotion of inclusive and equitable education. This dimension also considers the long-term benefits for the community, such as increased student engagement, improved academic performance, and the overall well-being of students and teachers. Social impact is evaluated through various indicators, including qualitative feedback from participants or quantitative data on school metrics, for example.

This process ensured that the included studies provide comprehensive data to understand the characteristics and the social impact of different teacher-training programs.

3. Results

The characteristics of the included studies are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Studies included.

3.1. Type of Teacher Training

Various forms and types of teacher training are known, particularly for addressing school violence. The selected articles explore different programs and methods used to train teachers in reducing violence in their schools. Despite the diversity of these programs, many share common characteristics in terms of training approaches.

Several studies highlight the importance of utilizing techniques, strategies, and interventions grounded in scientific evidence to ensure the effectiveness of the implemented interventions [52,53,54,55,56]. In addition, some of the studies analyzed [57,58] specify the importance of using scientific evidence that demonstrates social impact. This type of evidence, known as scientific evidence of social impact, highlights actions that lead to improvements in addressing identified problems and, consequently, enhance the lives of the people involved. Specifically, the educational practices linked to scientific evidence of social impact include dialogic teacher training implemented in a school for 0–3-year-olds [58] and within a professional development network for early childhood, primary, and secondary education teachers [57].

Some studies also emphasize [54,56,58] the importance of ongoing training for teachers. This continuous professional development allows teachers to expand their knowledge and skills, enabling them to provide the highest-quality education to their students. Providing sufficient training and ongoing supervision to staff is essential, as skills develop over time and with practice [56]. Additionally, regular reinforcement of training throughout the course is important for continued improvement [54]. In one of the studies, participating teachers had received training for at least two years [57], while another study documented a school with continuous training for over 16 years [58].

Additionally, involving non-teaching community members in training alongside teachers has also been considered in some of the studies [57,58,59,60]. This includes university researchers or observatory staff [59], committee members [60], administrators, canteen assistants, family members, and other individuals interested in contributing to the school [57,58]. These studies report that community-based approaches, which involve stakeholders beyond just teachers and students, have a very positive impact on reducing school violence and improving the quality of relationships.

A common feature of nearly all studies was group discussion [48,52,54,59,61], underscoring the significance of dialogue among teachers. The majority of the studies utilized workshops and training modules with teachers. The strategies employed in these sessions were diverse, encompassing reflective practice [48,55], brainstorming and card-sorting activities [52,55], live and videotape modeling [52,55,56], role-play and rehearsal [48,52,55,59,61], demonstrations [47,52,53,55,56], and the use of vignettes [48,55,60]. Some of the studies [57,58] were based on dialogic teacher training, an approach in which participants share readings about prominent authors internationally known for their contributions to educational improvement, as well as updated scientific research. This is always conducted through egalitarian dialogue among participants, where the most relevant arguments prevail over power dynamics [62].

3.2. Content of Teacher Training

Regarding the content addressed in the various studies and teacher-training programs aimed at reducing school violence, it has been observed that certain topics recur across different actions and programs. In other words, some characteristics of the content are mentioned in multiple studies.

A recurrent theme in several studies is the training of teachers on the importance of bystander intervention. A key component of the Zero Violence Brave Club is the protection of both victims and those who defend them, encouraging peers to become upstanders [57]. In Dialogic Pedagogical Gatherings (DPGs), strategies to prevent bullying and school violence are discussed among teachers, with a strong emphasis on the significance of bystander intervention [58]. Breaking the silence and motivating bystanders to support victims are also a central focus of teacher-training programs [57,58,60]. Promoting solidarity among students is essential and is therefore incorporated into teacher-training programs. The PBIS curriculum offers various approaches to help students develop skills for interacting with and supporting their peers [54]. Similarly, in the Zero Violence Brave Club, emphasis is placed on the importance of standing up for and supporting victims. Teachers convey these values to their students, thus fostering positive attitudes toward victims and encouraging students to protect and befriend them [57].

In cases of school violence, perpetrators frequently attain social status and are often perceived as popular and/or attractive [57,58]. This status is not achieved despite having negative attitudes toward peers but is rather attained precisely through aggression toward peers. Consequently, these contexts create pressure among participants to perceive violence and popularity as closely linked elements. To counteract this tendency and to elevate the status of individuals who exhibit ethically based behaviors, supportiveness, and positive interactions, some of the selected studies address this issue with trainee teachers, as introducing praise and attention to positive behavior in the classroom—by emphasizing that such behavior is “cool” [53,56]—can add value to alternative behaviors and make kindness appealing to children. This approach involves a collective effort by teachers to replace the language of ethics—which distinguishes what is ethically correct from what is not— with the language of desire—which focuses on generating attractiveness—about ethically based behaviors, demonstrating that what is desirable and attractive can also be positive and non-violent [57]. Additionally, another study underscores the importance of educators using the language of desire, rather than solely the language of ethics, by focusing on and reinforcing positive attitudes [58].

Other content covered in the training programs includes providing emotional support [47,52,53,54,55,56]. For example, one of the interventions [53] promotes class-wide prosocial behavior and high-quality emotional support to create a more emotionally supportive classroom environment. Another intervention [52] focuses on creating more supportive environments by providing training in classroom behavior management and promoting children’s social–emotional competence. Another program analyzed provides training to ensure that all students are involved in preventing the development of bullying behaviors and that every student has access to support [54].

Furthermore, several studies emphasize the importance of developing emotional and social skills [47,52,53,54,55,56] and fostering friendships [57,58]. Among the topics covered, some of these interventions focus on fostering friendships to effectively address school violence, emphasizing the protective role of high-quality peer relationships. They aim to distinguish genuine friendships from negative ones and promote the attractiveness of supportive and positive friendships. By doing so, they seek to create a safer and more inclusive school environment, reducing the risk of violence and enhancing student well-being.

Some studies also emphasize the importance of developing awareness of the consequences of school violence in all of its forms and the need for intervention to address it [47,53,55,57,61,63]. The responsibility of teachers to intervene in cases of aggression and to raise awareness about the issue is highlighted. Additionally, another key topic is the prioritization of prevention as an essential approach to address school violence effectively [47,53,57,58,59,61].

Other than that, in several studies [47,52,53,55,56,57], teachers learn to address the prevention and management of behavioral problems through rule-setting as key for prevention and intervention. In some studies [47,52,53,55,56], problem-solving stories and visual aids, such as picture cards, were used to facilitate the instruction of classroom rules, friendship skills, and emotional understanding. Another study [57] emphasizes the importance of establishing norms through community-based democratic processes and highlights the crucial role of students in taking responsibility and playing an active role in upholding these norms.

3.3. Social Impact Achieved

The following section presents the social impact achieved through the previously described training programs. The analyzed studies report various types of social impact, including a reduction in school violence, an improvement in school climate, academic advancements, and broader social improvements. The studies analyzed attribute these positive changes to the specific training provided to teachers.

All articles reviewed indicate that teacher-training programs effectively contributed to the reduction of violence in schools. Pupil-to-pupil violence was reduced [48,58,59,60,61]. Additionally, in Constantine and colleagues’ study, students reported a decrease in the number of bullying episodes in all areas of bullying explored, including verbal, physical, and indirect bullying. Verbal harassment showed the most significant decrease, followed by physical harassment. Moreover, not only was peer violence reduced, but other studies also reported a noticeable decrease in teacher violence toward students. Specifically, there were fewer instances of violence against children by teachers in intervention schools compared to control schools in the post-intervention phase [47,52,53,55,56].

Many studies demonstrate that the school climate improves and better relationships are built. The quality of the school climate improves [47,52,53], thus fostering better relationships and friendships [56,60]. In one study, teachers reported that pupils now offer help and assistance without being asked and without belittling classmates with difficulties. They also observed that students look out for each other and ensure that everyone has someone to play with or talk to. Support for each other has increased, creating a greater sense of community [48,63].

Another frequently reported impact is bystander intervention. This means that students raise their voices, break the silence, and support the victim. For this to happen, teachers must provide their students with the necessary tools and support [54,57,60]. Once this dynamic is established, many students are more willing to help and encourage each other [48,57]. Equipped with these tools and motivated by a sense of solidarity, students find it easier to break the silence by, for example, reporting incidents to teachers to protect the victim [54,60].

Teachers also directly benefited in several studies [48,56,60,63]. Teachers’ well-being markedly improved, with less stress, increased calmness, and greater enjoyment [48,63]. Seeing the success and improvement of their students inspires teachers to continue their work with enthusiasm and joy [63]. For instance, one study mentions that teachers feel more confident in identifying sexual abuse against children because of the training [60]. Another study noted that improved relationships with students led to enhanced professional well-being, increased motivation, and improved knowledge and skills [56].

The involvement of families and non-teaching staff is another impact highlighted in some studies. Inviting diverse families, including immigrant families, to participate in small groups was found to increase cultural sensitivity [54]. In addition, teachers experienced an improvement in their relationships with their students’ parents, feeling more supported and comfortable working with families [57] and dreaming of a unified purpose for the whole educational community, including staff, families, and students themselves [58].

Furthermore, improved coexistence is shown to correlate with better academic results in numerous studies. Some articles demonstrate how students improve their academic skills and results [48,57] while simultaneously reducing school violence. For younger pupils, interventions to reduce violence benefited early learning skills, particularly oral language and self-regulation skills [53]. Teachers in another study reported unprecedented progress in reading skills [63].

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [1] have prioritized making schools safe spaces, highlighting this as an essential component of quality education under SDG 4. This poses a significant challenge, as data indicate the widespread prevalence of school violence globally and its harmful effects on educational achievement, social relationships, and health, with potentially long-lasting consequences.

Research has demonstrated that teachers can play a crucial role in overcoming school violence. The scientific literature shows that teachers who receive effective training are better-equipped to address this issue [44,45,46]. Additionally, the scientific literature shows that there are core components that can be applied across different countries and cultures [47]. These components help teachers transition from feeling isolated and powerless to learning how to effectively address school violence [48]. Therefore, it is crucial to identify what type of teacher-training programs enable educators to play an important role.

This literature review aimed to analyze research studies that have demonstrated improvements in overcoming school violence through the implementation of specific teacher-training programs. The primary goal was to identify the characteristics that these studies reported as being linked to the success of the teacher-training programs analyzed. To achieve this, three research questions were formulated to identify the type of training, the content covered in the training, and the impact achieved by the teacher-training programs examined.

Regarding the type of teacher training, the studies analyzed highlight the importance of grounding these programs in scientific evidence, particularly evidence demonstrating how to achieve improvements, i.e., scientific evidence with a social impact. The studies also provide evidence of the importance of creating interactions and dialogue in which teachers can collaborate to share concerns, challenges, and solutions. Additionally, some studies emphasize the importance of involving other educational stakeholders, such as families, in the training process, as well as ensuring that the training programs are sustained over time.

These characteristics align with research that emphasizes the importance of evidence-based educational practices with social impact, involving families and the community, and making dialogue central to education. Moreover, the studies analyzed demonstrate that for teacher training to be effective in addressing school violence, it must have the appropriate characteristics. The key is not only to offer teachers the right content but also to ensure that the types of interaction and dialogue developed during the training will allow for success.

These findings support the already established view that what has been referred to as “banking education” [64] is not the model that guarantees teachers will return to their schools and contribute to overcoming violence. Nor do these studies align with the approach that views teacher training as an individual responsibility of each teacher [65]. On the contrary, the evidence collected in these studies points to the need for teacher training to be conducted as a collective activity, where collaboration thrives within the context of individual freedom. This aligns with the theory of a dialogic society, which posits that egalitarian dialogue between citizens and science is increasingly becoming the driving force behind improving people’s lives [66].

Additionally, the studies analyzed in this literature review highlight several key content areas. These include bystander intervention strategies to break the silence surrounding school violence and to encourage individuals to take a stand in protecting victims, with an emphasis on raising awareness of the consequences of violence. The importance of addressing trends that associate violence with attractiveness and popularity is also emphasized, with the aim of linking ethical behavior to what is considered attractive and popular while diminishing the appeal of violent attitudes. Additionally, some studies underscore the need to foster high-quality human relationships and supportive environments.

These content areas align with well-established research, such as the critical importance of bystander intervention [67] and the need to counteract the coercive discourse that links attractiveness and violence by using the language of desire to promote the appeal of ethical behaviors [68].

The studies analyzed in this literature review also highlight a wide range of behaviors considered to be school violence. These align with the World Health Organization’s [69] definition of violence against children, which includes physical, sexual, and emotional abuse and neglect inflicted by parents, other adults, peers, or intimate partners. Therefore, the studies show that school violence encompasses various types of acts committed by different actors, emphasizing the importance of addressing all of these forms comprehensively.

Moreover, the studies analyzed in this literature review provide evidence of various types of social impact, including reductions in violence, improved school climate and friendships, increased bystander intervention, enhanced teacher well-being, greater family and community involvement, and improved academic outcomes. These impacts align with the overarching goals outlined in the Sustainable Development Goals and underscore the effectiveness of the interventions reported in these studies.

Furthermore, the analyzed research demonstrates that a healthy school environment heavily depends on the interventions implemented, and that effective teacher training can be a significant catalyst for positive change. Therefore, these findings highlight the importance of human agency and the potential to achieve substantial progress when the appropriate actions are taken. Although school violence may seem deeply entrenched and insurmountable, these studies reveal that the opposite is true. However, success does not merely depend on good intentions; it is crucial to select interventions that truly contribute to overcoming violence.

When stating that teachers can play a key role in effectively addressing school violence, this does not mean that the responsibility falls solely on them. The studies analyzed in this literature review indicate that the training teachers receive has a crucial influence. Therefore, these findings suggest that the effectiveness of teachers largely depends on other stakeholders who contribute to shaping teacher training, including public policies, universities, and other institutions dedicated to education.

School violence is a major challenge due to its global prevalence and the harm it causes academically, socially, and health-wise. Teachers have the potential to play a crucial role in combating this issue, but it is essential that the training they receive genuinely equips them for this purpose. Such training is essential to ensure that all students can thrive in safe, violence-free environments. This study provides evidence that helps shed light on the types of training that effectively prepare teachers to address school violence.

5. Limitations

The present literature review has several limitations that need to be acknowledged. Firstly, because only scientific articles written in English were selected, the literature review is limited in this regard. Additionally, due to the extensive screening required, the risk of bias is quite high. As a result, the transferability of the findings is significantly limited. For future research, it would be advisable to include scientific articles in all languages and to expand the literature review to other educational programs, such as those for pre-service teachers. Moreover, to reduce the risk of screening bias, it would be beneficial to broaden and refine the eligibility criteria by selecting those that minimize the need for extensive screening.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.O. and H.Z.-E.; methodology, A.O. and H.Z.-E.; formal analysis, A.O., H.Z.-E., S.C. and J.M.C.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.O.; writing—review and editing, H.Z.-E., A.O., S.C. and J.M.C.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by a research contract from the Basque Government under Grant “PRE_2022_1_0266”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data from this study are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations. 2015. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 16 July 2024).

- UNESCO. Behind the Numbers: Ending School Violence and Bullying. UNESCO. 2019. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000366483 (accessed on 21 July 2024).

- World Health Organization. School-Based Violence Prevention: A Practical Handbook; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/324930 (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Hillis, S.; Mercy, J.A.; Amobi, A.; Kress, H. Global prevalence of past-year violence against children: A systematic review and minimum estimates. Pediatrics 2016, 137, e20154079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF. An Everyday Lesson. #ENDviolence in Schools. UNICEF. 2018. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/documents/everyday-lesson-endviolence-schools (accessed on 15 March 2024).

- Nansel, T.R.; Overpeck, M.D.; Pilla, R.S.; Ruan, W.J.; Simons-Morton, B.; Scheidt, P. Bullying behaviors among US youth: Prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. JAMA 2001, 285, 2094–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNICEF. Hidden in Plain Sight: A Statistical Analysis of Violence against Children. UNICEF. 2014. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/resources/hidden-in-plain-sight-a-statistical-analysis-of-violence-against-children/ (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- UNESCO. School Violence and Bullying: Global Status Report; UNESCO: London, UK, 2017; Volume 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Iannotti, R.J.; Nansel, T.R. School Bullying among Adolescents in the United States: Physical, Verbal, Relational, and Cyber. J. Adolesc. Health 2009, 45, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wodon, Q.; Fevre, C.; Male, C.; Nayihouba, A.; Nguyen, H. Ending Violence in Schools: An Investment Case; The World Bank and the Global Partnership to End Violence Against Children: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/470341626799342515/pdf/Ending-Violence-in-Schools-An-Investment-Case.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Gershoff, E.T. School Corporal Punishment in Global Perspective: Prevalence, Outcomes, and Efforts at Intervention. Psychol. Health Med. 2017, 22, 224–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogando Portela, M.J.; Pells, K. Corporal Punishment in Schools: Longitudinal Evidence from Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Viet Nam (Innocenti Discussion Paper No. 2015-02); UNICEF Office of Research: Florence, Italy, 2015; Available online: https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/series/22/ (accessed on 25 June 2024).

- Busch, V.; Loyen, A.; Lodder, M.; Schrijvers, A.J.P.; van Yperen, T.A.; de Leeuw, J.R.J. The Effects of Adolescent Health-Related Behavior on Academic Performance: A Systematic Review of the Longitudinal Evidence. Rev. Educ. Res. 2014, 84, 245–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Vaillancourt, T.; Brittain, H.L.; McDougall, P.; Krygsman, A.; Smith, D.; Cunningham, C.E.; Haltigan, J.D.; Hymel, S. School climate, peer victimization, and academic achievement: Results from a multi-informant study. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2014, 29, 360–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Más Allá de los Números: Poner fin a la Violencia y el Acoso en el Ámbito Escolar. UNESCO. 2021. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000378398 (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Dalla Pozza, V.; Di Pietro, A.; Morel, S.; Psaila, E. Cyberbullying among Young People; Directorate General for Internal Policies, Policy Department, Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, S.E.; Norman, R.E.; Suetani, S.; Thomas, H.J.; Sly, P.D.; Scott, J.G. Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Psychiatry 2017, 7, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seedat, S.; Stein, M.B.; Kennedy, C.M.; Hauger, R.L. Plasma cortisol and neuropeptide Y in female victims of intimate partner violence. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2003, 28, 796–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shonkoff, J.P.; Garner, A.S.; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health; Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, and Dependent Care; Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e232–e246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.-Y.; Meaney, M.J. Epigenetics and the environmental regulation of the genome and its function. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2010, 61, 439–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flecha, R.; Puigvert, L.; Racionero-Plaza, S. Achieving Student Well-Being for All: Educational Contexts Free of Violence. NESET Report. 2023. Available online: https://nesetweb.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/NESER_AR1_full_report-KC-2.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Pivik, J.; McComas, J.; Laflamme, M. Barriers and Facilitators to Inclusive Education. Except. Child. 2002, 69, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, D.E.; Veenstra, R.; Ormel, J.; Verhulst, F.C.; Reijneveld, S.A. Early Risk Factors for Being a Bully, Victim, or Bully/Victim in Late Elementary and Early Secondary Education. The Longitudinal TRAILS Study. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caravita, S.C.S.; Stefanelli, S.; Mazzone, A.; Cadei, L.; Thornberg, R.; Ambrosini, B. When the Bullied Peer Is Native-Born vs. Immigrant: A Mixed-Method Study with a Sample of Native-Born and Immigrant Adolescents. Scand. J. Psychol. 2019, 61, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, C.A.; Espelage, D.L.; Monda-Amaya, L.E. Bullying and Victimisation Rates among Students in General and Special Education: A Comparative Analysis. Educ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 761–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symes, W.; Humphrey, N. Peer-Group Indicators of Social Inclusion among Pupils with Autistic Spectrum Disorders (ASD) in Mainstream Secondary Schools: A Comparative Study. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2010, 31, 478–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earnshaw, V.A.; Reisner, S.L.; Juvonen, J.; Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Perrotti, J.; Schuster, M.A. LGBTQ Bullying: Translating Research to Action in Pediatrics. Pediatrics 2017, 140, e20170432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschstein, M.K.; van Schoiack Edstrom, L.; Frey, K.S.; Snell, J.L.; MacKenzie, E.P. Walking the Talk in Bullying Prevention: Teacher Implementation Variables Related to Initial Impact of the Steps to Respect Program. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 36, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodge, J.; Frydenberg, E. The Role of Peer Bystanders in School Bullying: Positive Steps toward Promoting Peaceful Schools. In Peace Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 329–336. [Google Scholar]

- Mahon, J.; Packman, J.; Liles, E. Preservice Teachers’ Knowledge about Bullying: Implications for Teacher Education. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ. 2020, 93, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, A.; Cross, D.; Lester, L.; Hearn, L.; Epstein, M.; Monks, H. The Invisibility of Covert Bullying among Students: Challenges for School Intervention. J. Psychol. Couns. Sch. 2012, 22, 206–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, W.M.; Pepler, D.; Atlas, R. Observations of Bullying in the Playground and in the Classroom. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2000, 21, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, C.P.; Sawyer, A.L.; O’Brennan, L.M. Bullying and Peer Victimization at School: Perceptual Differences Between Students and School Staff. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2007, 36, 361–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, R.S.; Gross, A.M. Childhood Bullying: Current Empirical Findings and Future Directions for Research. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2004, 9, 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.S.; Kerber, K. Bullying: Elementary Teachers’ Attitudes and Intervention Strategies. Res. Educ. 2003, 69, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochenderfer-Ladd, B.; Pelletier, M.E. Teachers’ Views and Beliefs about Bullying: Influences on Classroom Management Strategies and Students’ Coping with Peer Victimization. J. Sch. Psychol. 2008, 46, 431–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pšunder, M. The Identification of Teasing Among Students as an Indispensable Step Towards Reducing Verbal Aggression in Schools. Educ. Stud. 2010, 36, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blain-Arcaro, C.; Smith, J.D.; Cunningham, C.E.; Vaillancourt, T.; Rimas, H. Contextual Attributes of Indirect Bullying Situations That Influence Teachers’ Decisions to Intervene. J. Sch. Violence 2012, 11, 226–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, M.J.; Hardcastle, K.; Down, J.; Fowles, J.; Simmonds, J.A. A Comparison of Preservice Teachers’ Responses to Cyber versus Traditional Bullying Scenarios: Similarities and Differences and Implications for Practice. J. Teach. Educ. 2014, 65, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaides, S.; Toda, Y.; Smith, P.K. Knowledge and Attitudes about School Bullying in Trainee Teachers. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2002, 72, 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Veenstra, R.; Lindenberg, S.; Munniksma, A.; Dijkstra, J.K. The Complex Relation Between Bullying, Victimization, Acceptance, and Rejection: Giving Special Attention to Status, Affection, and Sex Differences. Child Dev. 2010, 81, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, S. Do we need more measures of bullying? J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 59, 487–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espelage, D.L.; Polanin, J.R.; Low, S.K. Teacher and Staff Perceptions of School Environment as Predictors of Student Aggression, Victimization, and Willingness to Intervene in Bullying Situations. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2014, 29, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adi, Y.; Killoran, A.; Janmohamed, K.; Stewart-Brown, S. Systematic Review of the Effectiveness of Interventions to Promote Mental Wellbeing in Primary Schools: Universal Approaches Which Do Not Focus on Violence or Bullying. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. 2007. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK73674/ (accessed on 26 July 2024).

- Berkowitz, M.W.; Bier, M.C. What Works in Character Education: A Research-Driven Guide for Educators. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Marvin-Berkowitz-2/publication/251977043_What_Works_In_Character_Education/links/53fb5ea60cf22f21c2f31c28/What-Works-In-Character-Education.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Diekstra, R.F.; Gravesteijn, C. Effectiveness of School-Based Social and Emotional Education Programmes Worldwide. In Social and Emotional Education: An International Analysis; SCIRP: Glendale, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 255–312. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Rene-Diekstra-2/publication/255620397_Efectiveness_of_School-Based_Social_and_Emotional_Education_Programmes_Worldwide/links/555e0c9c08ae8c0cab2c5e7e/Efectiveness-of-School-Based-Social-and-Emotional-Education-Programmes-Worldwide.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Baumgarten, E.; Simmonds, M.; Mason-Jones, A.J. School-Based Interventions to Reduce Teacher Violence against Children: A Systematic Review. Child Abus. Rev. 2022, 32, e2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nye, E.; Melendez-Torres, G.J.; Gardner, F. Mixed Methods Systematic Review on Effectiveness and Experiences of the Incredible Years Teacher Classroom Management Programme. Rev. Educ. Res. 2019, 7, 631–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, D.N.; Sass, T.R. Teacher Training, Teacher Quality and Student Achievement. J. Public Econ. 2011, 95, 798–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flecha, R.; Radauer, A.; van den Besselaar, P. Monitoring the Impact of EU Framework Programmes. European Commission. 2018. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/cbb7ce39-d66d-11e8-9424-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Page, M.J.; Mckenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker-Henningham, H.; Bowers, M.; Francis, T.; Vera-Hernandez, M.; Walker, S.P. The Irie Classroom Toolbox, a Universal Violence-Prevention Teacher-Training Programme, in Jamaican Preschools: A Single-Blind, Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, E456–E468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker-Henningham, H.; Scott, Y.; Bowers, M.; Francis, T. Evaluation of a Violence-Prevention Programme with Jamaican Primary School Teachers: A Cluster Randomised Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letendre, J.; Ostrander, J.A.; Mickens, A. Teacher and Staff Voices: Implementation of a Positive Behavior Bullying Prevention Program in an Urban School. Child. Sch. 2016, 38, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker-Henningham, H.; Bowers, M.; Francis, T. The Process of Scaling Early Childhood Violence Prevention Programs in Jamaica. Pediatrics 2023, 151, e2023-060221M. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, M.; Francis, T.; Baker-Henningham, H. The Irie Classroom Toolbox: Mixed Method Assessment to Inform Future Implementation and Scale-up of an Early Childhood, Teacher-Training, Violence-Prevention Programme. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1040952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca-Campos, E.; Duque, E.; Rios, O.; Ramis-Salas, M. The Zero Violence Brave Club: A Successful Intervention to Prevent and Address Bullying in Schools. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 601424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Oramas, A.; Zubiri, H.; Arostegui, I.; Serradell, O.; Sanvicen-Torne, P. Dialogue with Educators to Assess the Impact of Dialogic Teacher Training for a Zero-Violence Climate in a Nursery School. Qual. Inq. 2020, 26, 1019–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, C.; Casuccio, A.; Marotta, C.; Bono, S.E.; Ventura, G.; Mazzucco, W.; BIAS Study Working Group. Effects of an Intervention to Prevent the Bullying in First-Grade Secondary Schools of Palermo, Italy: The BIAS Study. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2019, 45, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madrid, B.J.; Lopez, G.D.; Dans, L.F.; Fry, D.A.; Duka-Pante, F.G.H.; Muyot, A.T. Safe Schools for Teens: Preventing Sexual Abuse of Urban Poor Teens, Proof-of-Concept Study—Improving Teachers’ and Students’ Knowledge, Skills and Attitudes. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowes, L.; Aryani, F.; Ohan, F.; Haryanti, R.H.; Winarna, S.; Arsianto, Y.; Budiyawati, H.; Widowati, E.; Saraswati, R.; Kristianto, Y.; et al. The Development and Pilot Testing of an Adolescent Bullying Intervention in Indonesia—The ROOTS Indonesia Program. Glob. Health Action 2019, 12, 1656905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flecha, R. Sharing Words: Theory and Practice of Dialogic Learning; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Diamond, A.; Lee, C.; Senften, P.; Lam, A.; Abbott, D. Randomized Control Trial of Tools of the Mind: Marked Benefits to Kindergarten Children and Their Teachers. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitts, H. ‘It’s like Freire is haunting me’: The value of study groups for critical teacher professional development. Prof. Dev. Educ. 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiff, D.; Herzog, L.; Farley-Ripple, E.; Thum Iannuccilli, L. Teacher Networks in Philadelphia: Landscape, Engagement, and Value. Urban Educ. 2015, 12. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1056676 (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Flecha, R. The Dialogic Society. The Sociology Scientists and Citizens Like and Use; Hipatia Press: Barcelona, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Thapa, A.; Cohen, J.; Guffey, S.; Higgins-D’Alessandro, A. A Review of School Climate Research. Rev. Educ. Res. 2013, 83, 357–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puigvert, L.; Gelsthorpe, L.; Soler-Gallart, M.; Flecha, R. Girls’ Perceptions of Boys with Violent Attitudes and Behaviours, and of Sexual Attraction. Palgrave Commun. 2019, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Violence against Children. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-children (accessed on 21 August 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).