McLuhan’s Tetrad as a Tool to Interpret the Impact of Online Studio Education on Design Studio Pedagogy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

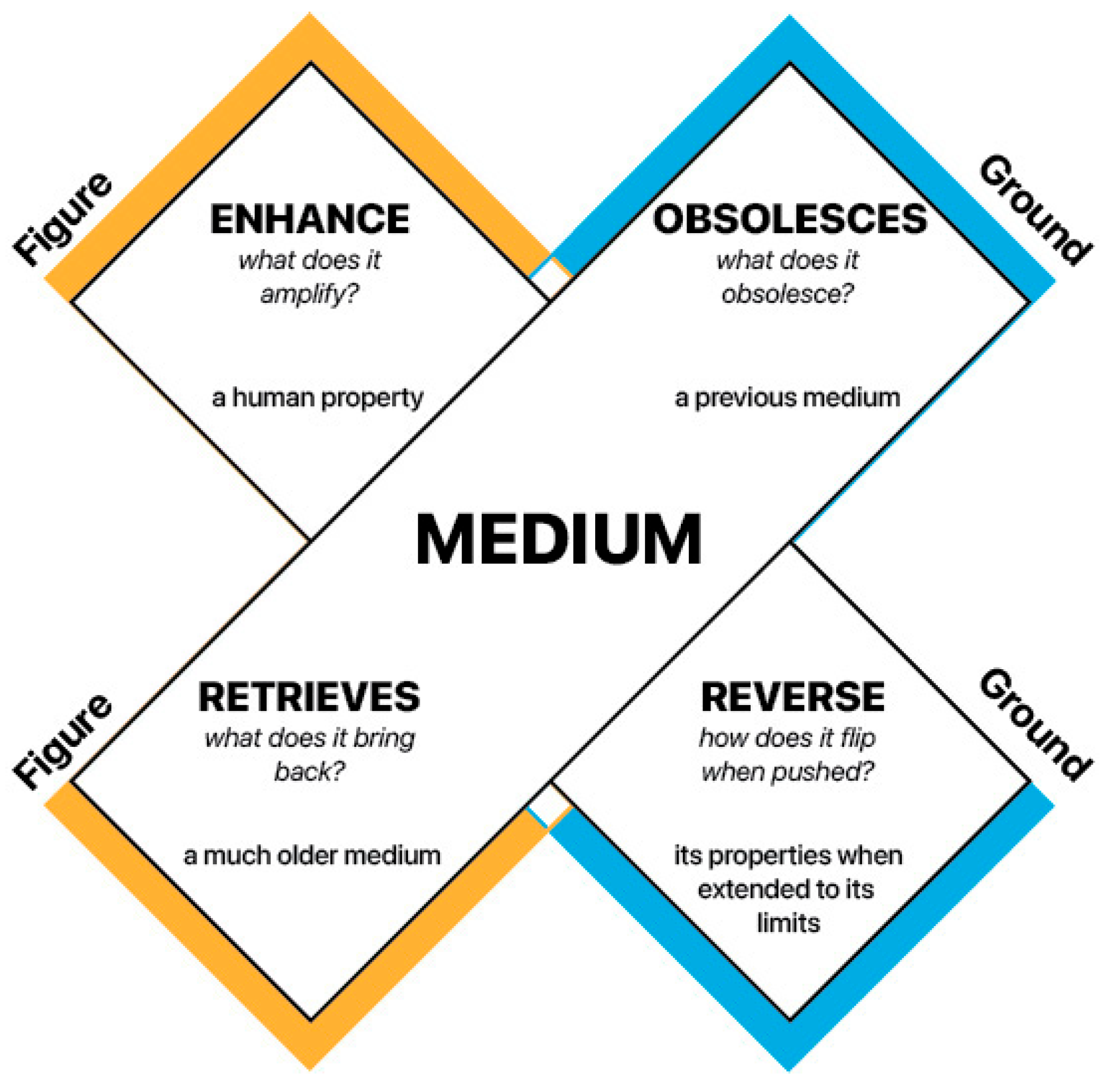

- What does the medium enhance, referring to the way in which a new medium enhances or amplifies an existing medium?

- What does the new medium make obsolete, or in other terms, does the new medium eventually render an existing medium obsolete?

- What does the medium retrieve that had been obsolesced earlier, referring to how a new medium can bring back something that was previously lost or forgotten?

- What does the medium reverse or flip into when pushed to extremes, describing how a new medium can eventually be used in a way that is opposite to its original intended purpose?

2. Materials and Methods

3. Architectural Design Studio as a Pedagogical Setting

4. The Online Studio from a Tetradic Framework

4.1. Setting

4.2. Actors

4.3. Outputs

4.4. Dynamics

5. Limitations of the Study and Future Research

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McLuhan, M. Laws of the Media. ETC Rev. Gen. Semant. 1977, 34, 173–179. [Google Scholar]

- McLuhan, M.; Powers, B.R. The Global Village: Transformations in World Life and Media in the 21st Century; Communication and Society; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989; ISBN 9780195079104. [Google Scholar]

- Sandstrom, G. Laws of Media—The Four Effects: A McLuhan Contribution to Social Epistemology. Soc. Epistemol. Rev. Reply Collect. 2012, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Adam, I. What Would McLuhan Say about the Smartphone? Applying McLuhan’s Tetrad to the Smartphone. Glocality 2016, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLuhan, M.; McLuhan, E. Laws of Media: The New Science; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, Canada, 1992; ISBN 9780802077158. [Google Scholar]

- Salama, A.M.; Burton, L.O. Defying a Legacy or an Evolving Process? A Post-Pandemic Architectural Design Pedagogy. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Urban Des. Plan. 2022, 175, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, A.M.; Crosbie, M.J. Educating Architects in a Post-Pandemic World. Available online: https://strathprints.strath.ac.uk/77141/7/Salama_Crosbie_CE_2020_Educating_architects_in_a_post_pandemic_world.pdf (accessed on 10 December 2023).

- Mahmoud Saleh, M.; Abdelkader, M.; Sadek Hosny, S. Architectural Education Challenges and Opportunities in a Post-Pandemic Digital Age. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 102027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, S.; Şahin, P.; Seçmen, S.; Elif, S.M.; Süher, K.H. An Evaluation of Online Architectural Design Studios during COVID-19 Outbreak. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2020, 15, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnusairat, S.; Duaa, A.M.; Al-Jokhadar, A. Architecture Students’ Satisfaction with and Perceptions of Online Design Studios during COVID-19 Lockdown: The Case of Jordan Universities. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2020, 15, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zairul, M.; Azli, M.; Azlan, A. Defying Tradition or Maintaining the Status Quo? Moving towards a New Hybrid Architecture Studio Education to Support Blended Learning Post-COVID-19. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2023, 17, 554–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haridy, N.M.; Khalil, M.H.; Bakir, R. The Dynamics of Design- Knowledge Construction: The Case of a Freshman Architectural-Design Studio in Egypt. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 2022, 21, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranmanesh, A.; Onur, Z. Mandatory Virtual Design Studio for All: Exploring the Transformations of Architectural Education amidst the Global Pandemic. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2021, 40, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranmanesh, A.; Onur, Z. Generation Gap, Learning from the Experience of Compulsory Remote Architectural Design Studio. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High Educ. 2022, 19, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrina, T.; Huang, A.; Hui, V.; Sarmiento, K. Transitioning Architectural Pedagogy into the Virtual Era via Digital Learning Methods. Educ. New Developments 2021, 2021, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maani, D.A.; Alnusairat, S.; Al-Jokhadar, A. Transforming Learning for Architecture: Online Design Studio as the New Norm for Crises Adaptation Under COVID-19. Open House Int. 2021, 46, 348–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarzyńska-Świeściak, E.; Adams, B.; Thomas, L. Transition from Physical Design Studio to Emergency Virtual Design Studio. Available Teaching and Learning Methods and Tools—A Case Study. Buildings 2021, 2021, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanpour, B. Transformational Contribution of Technology to Studio Culture: Experience of an Online First-Year Architecture Design Studio During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2022, 17, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.; Fox, J.; Sleight, J.; Oldfield, P. The Online Studio: Cultures, Perceptions and Questions for the Future. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2023, 42, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatta, R.T.A.; Momani, H.M.; Bataineh, A. The Effect of Online Teaching on Basic Design Studio in the Time of COVID-19: An Application of the Technology Acceptance Model. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2022, 66, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadpour, A. Student Challenges in Online Architectural Design Courses in Iran During the COVID-19 Pandemic. E-Learn. Digit. Media 2021, 18, 511–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, R.; Wright, A.D. Shutting the Studio: The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Architectural Education in the United Kingdom. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2022, 33, 1173–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.; Burns, S.P.; Wilson, M.A. Socio-Constructivist Pedagogy in Physical and Virtual Spaces: The Impacts and Opportunities on Dialogic Learning in Creative Disciplines. Architecture_mps 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Ostwald, M.J.; Gu, N.; Skates, H.; Feast, S. Evaluating the Effectiveness of Online Teaching in Architecture Courses. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2022, 65, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asfour, O.S.; Alkharoubi, A.M. Challenges and Opportunities in Online Education in Architecture: Lessons Learned for Post-Pandemic Education. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 102131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilter, A.T. Design Studio in Case of Emergency: Implications for Future Digitalized Educational Experiences. Grid Archit. Plan. Des. J. 2023, 6, 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhusban, A.A.; Alhusban, S.A.; Alhusban, M.-W.A. Assessing the Impact of COVID-19 on Architectural Education: A Case Study of Jordanian Universities. Educ. Train. 2023, 65, 749–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekici, B.B.; Akyıldız, N.A.; Karabatak, S.; Alanoğlu, M. Architecture Students’ Attitudes Toward Emergency Distance Education and Elements Affecting Their Success in Design Studios: A Sample from Turkey. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ. 2023, 34, 853–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfabadi, P.; Mousavi, S.A. Adaptation of Architectural Education Pedagogy in Addressing COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Educ. Technol. Online Learn. 2022, 5, 1094–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megahed, N.A.; Hassan, A.M. A Blended Learning Strategy: Reimagining the Post-COVID-19 Architectural Education. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2021, 16, 184–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis; SAGE Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.B.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Turner, L.A. Toward a Definition of Mixed Methods Research. J. Mix. Methods Res. 2007, 1, 112–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D.A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action; Reprinted; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 1983; ISBN 9781857423198. [Google Scholar]

- McLuhan, M. Understanding Media, 1st ed.; McGraw-Hill Paperbacks: New York, NY, USA, 1964; ISBN 9780070454354. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D.A. Toward a Marriage of Artistry & Applied Science in the Architectural Design Studio. J. Archit. Educ. (1984-) 1988, 41, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, T.A. Design and Studio Pedagogy. J. Archit. Educ. 1987, 41, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendleton-Jullian, A. Four (+1) Studios; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: Scotts Valley, CA, USA, 2010; ISBN 9781449996345. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T. A New Paradigm for Design Studio Education. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2010, 29, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Türkkan, S. From Disruptions in Architectural Pedagogy to Disruptive Pedagogies for Architecture. In Disruptive Technologies: The Convergence of New Paradigms in Architecture; Morel, P., Bier, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2023; pp. 131–146. ISBN 9783031141607. [Google Scholar]

- Masatlioğlu, S.E. Stüdyo Kültürü: Ne Anlıyoruz? Available online: https://xxi.com.tr/i/studyo-kulturu-ne-anliyoruz (accessed on 22 August 2022).

- Shulman, L.S. Signature Pedagogies in the Professions. Daedalus 2005, 134, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, O. Design Studio Education in the Online Paradigm: Introducing Online Educational Tools and Practices to an Undergraduate Design Studio Course. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON), Athens, Greece, 25–28 April 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Türkkan, S. Mimarlık Eğitimini Mimarlık Eğitimi Yapan Bağzı Şeyler. Available online: https://xxi.com.tr/i/mimarlik-egitimini-mimarlik-egitimi-yapan-bagzi-seyler (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Schnabel, M.A.; Kvan, T.; Kruijff, E.; Donath, D. The First Virtual Environment Design Studio. eCAADe Proc. 2001, 394–400. [Google Scholar]

- Kvan, T. The Pedagogy of Virtual Design Studios. Autom. Constr. 2001, 10, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, M.L.; Simoff, S.J.; Cicognani, A. Understanding Virtual Design Studios (Computer Supported Cooperative Work), 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; ISBN 9781852331542. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann, K. Online Design Education: Searching for a Middle Ground. Arts Humanit. High. Educ. 2020, 19, 36–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLuhan, M.; Fiore, Q. The Medium Is the Massage: An Inventory of Effects; Gingko Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2001; ISBN 9781584230700. [Google Scholar]

- Gow, G. Spatial Metaphor in the Work of Marshall McLuhan. Can. J. Commun. 2001, 26, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLuhan, M.; Carpenter, E. Explorations in Communication: An Anthology; McLuhan, M., Carpenter, E., Eds.; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1960; ISBN 9780807061916. [Google Scholar]

- Lahtinen, M. The Medium Is the Message, or the Mediating Conditions for Informing Systems. In Proceedings of the 6th International Workshop on Socio-Technical Perspective in IS Development (STPIS 2020), Virtual, 28 December 2020; RWTH Aachen University: Aachen, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, M. The Pandemic Has Caused an Unprecedented Reckoning with Digital Culture. Architecture May Never Be the Same Again (and That’s Okay). Available online: https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/2020/04/the-global-pandemic-has-caused-an-unprecedented-reckoning-with-digital-culture-and-architecture-may-never-be-the-same-again-and-thats-okay/ (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- Belluigi, D.Z. Constructions of Roles in Studio Teaching and Learning. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2016, 35, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J.; Wenger, E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991; ISBN 9780521423748. [Google Scholar]

- Downes, S. Learning Networks and Connective Knowledge. In Collective Intelligence and E-Learning 2.0: Implications of Web-Based Communities and Networking; Yang, H.H., Yuen, S.C.-Y., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dreamson, N. Online Design Education: Meta-connective Pedagogy. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2020, 39, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, O. Opening up Design Studio Education Using Blended and Networked Formats. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2018, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, H. Architectural Education after Schön: Cracks, Blurs, Boundaries and Beyond. J. Educ. Built Environ. 2008, 3, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurillard, D. Rethinking University Teaching: A Conversational Framework for the Effective Use of Learning Technologies, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 9781136409059. [Google Scholar]

- Heywood, I. Making and the Teaching Studio. J. Vis. Art Pract. 2009, 8, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shreeve, A.; Simms, E.; Trowler, P. A Kind of Exchange: Learning from Art and Design Teaching. J. High. Educ. Dev. 2010, 29, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cennamo, K.S. What Is Studio?. In Studio Teaching in Higher Education: Selected Design Cases; Boling, E., Schwier, R., Gray, C., Smith, K., Campbell, K., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: Florence, Italy, 2016; pp. 248–259. [Google Scholar]

- McCullough, M. Abstracting Craft: The Practiced Digital Hand; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996; ISBN 9780262133265. [Google Scholar]

- Oxman, R. Digital Architecture as a Challenge for Design Pedagogy: Theory, Knowledge, Models and Medium. Des. Stud. 2008, 29, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masdéu, M.; Fuses, J. Reconceptualizing the Design Studio in Architectural Education: Distance Learning and Blended Learning as Transformation Factors. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2017, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrand, T.; Eliason, J. Feedback Practices and Signature Pedagogies: What Can the Liberal Arts Learn from the Design Critique? Teach. High. Educ. 2012, 17, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, K.H. Design Studios. In Companion to Urban Design; Banerjee, T., Loukaitou-Sideris, A., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2014; pp. 223–237. ISBN 9780203844434. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann, K. The Online Pandemic in Design Courses: Design Higher Education in Digital Isolation. In Impact of COVID-19 on the International Education System; Naumovska, L., Ed.; Proud Pen: London, UK, 2020; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lotz, N.; Jones, D.; Holden, G.; Holden, G. Social Engagement in Online Design Pedagogies. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference for Design Education Researchers, Chicago, IL, USA, 28–30 June 2015; Vande Zande, R., Ingvild, B.E.D., Eds.; Aalto University: Espoo, Finland, 2015; pp. 1645–1668. [Google Scholar]

| Authors/Paper | Topic/Themes | Supporting Quotations and Findings | |

| Estrina et al. [15] | feedback | There was a problem with effectively communicating and providing feedback, which could be due to various factors, such as a lack of clarity, inadequate channels of communication, or a breakdown in the feedback loop. | |

| student participation | Insufficient involvement of the students. | ||

| peer learning | Social connectivity decreased. | ||

| design review and evaluation asynchronous access | The students preferred virtual juries. Recordings allowed for in-depth learning. | ||

| digital tool proficiency | The lack of proficiency and efficiency in using digital technology was an issue. | ||

| Maani et al. [16] | feedback | The instructors’ feedback was not as frequent or sufficient as expected, resulting in low satisfaction rates. | |

| The learners demonstrated a higher level of self-reliance in their learning and took a more accountable approach toward making design choices. | |||

| student autonomy | |||

| Komarzynska-Swiesciak et al. [17] | virtual setting affordances | The students expressed high levels of satisfaction in relation to their time management, design, and presentation skills. | |

| delivery methods and tools | The available tools and methods necessitated a redefinition of the instructions. | ||

| Hassanpour [18] | student autonomy | It was possible for students to take on a more proactive approach in transferring the knowledge they have gained to making decisions. | |

| student participation | An educational culture that was not only focused on students but also directed by them, leading to a more integrated and participatory learning experience. | ||

| learning environment | Online education platforms faced challenges in maintaining the same bottom-up approach to education as on-site education due to its intuitive nature. | ||

| Murray et al. [19] | delivery methods and toolsengagement | There was not any decrease in user engagement when utilizing a mixture of software platforms. | |

| delivery methods and tools | There was a requirement to reassess the structures and procedures of the architectural design studio as the distribution of FTF, hybrid, and online studios changes. | ||

| peer interaction | The frequency of collaboration between peers diminished. | ||

| Alatta et al. [20] | virtual setting affordances asynchronous access | Virtual learning was flexible, efficient, and enjoyable, and could take place anytime and anywhere with the help of technology. | |

| student autonomy | Students were not passive observers but active participants in the learning process through self-based learning. | ||

| communication | There were difficulties in both hardware and software, obstacles with accessing the internet, and a lack of experience with the virtual environment. | ||

| Asadpour [21] | student participation | A low level of satisfaction was observed due to the dominance of the tutor-centered studio rather than being activity-oriented. | |

| student autonomy | Virtual education made the students to more positively rely on their abilities rather than the tutors’ assistance. | ||

| output media | Instead of physical models, digital models were favored. | ||

| Feedback | Insufficient understanding of the design objectives and feedback of their tutors. | ||

| communication | Access to technology and internet turned out to be a major issue. | ||

| tutor roles | Conventional roles of tutors as presenters or educators changed into counselors and facilitators. | ||

| Ceylan et al. [9] | output media | The most significant benefit of online studios was the use of digital tools for advanced visualization and representation. | |

| delivery methods and tools | The conventional and emerging education technologies needed to be merged. | ||

| Grover and Wright [22] | physical design studio | Teaching in the physical design studio was considered integral to architectural education by the students and staff. | |

| peer learning | Peer learning and support networks were particularly negatively affected by the closure of design studios. | ||

| communication | The quality of student and staff interactions was compromised. | ||

| Smith et al. [23]. | design reviews and evaluation | The hierarchical structure of virtual reviews was different from that which occurred in the physical studio, making it closer to becoming a student-oriented learning process. | |

| peer interaction | Tutors to focus on the social aspects of learning to encourage student interactions and discussion and to introduce strategies that counter feelings of disconnection. | ||

| communication | The dynamics of dialogic interaction arguably became different when occurring in virtual space as opposed to a physical place. | ||

| Iranmanesh and Onur [13] | communication and peer learning | Peer learning seemed to be the major part massing from VDS. | |

| delivery methods and tools | VDS requires both teachers and students to be familiar with a variety of new digital tools. | ||

| design reviews and evaluation | The hierarchical structure of VDS is different from PDS, making it closer to what it is supposed to be, a student-oriented learning process. | ||

| student autonomy | VDS provides an opportunity to increase the self-dependence and research-oriented design approach. | ||

| Iranmanesh and Onur [14] | communication | The two-sided communication happened in the physical studio over a table or a board; even a very simple working model is a precise and interactive medium and can convey ideas and comments quickly and intuitively. | |

| asynchronous access | Students were able to work on their projects while listening to the critique session and the availability of the recording helped them to pay better attention. Many students also revisited the recording to further improve their work. | ||

| design reviews and evaluation | The virtual jury seemed to empower students to focus on the strengths of their project by providing them more control over what was presented on the screen. | ||

| Yu et al. [24] | asynchronous access | Online teaching allowed students to be able to learn anywhere and with relatively flexible scheduling as well. | |

| delivery methods and tools | Online teaching tools for lecture-based non-studio architecture courses were functioning at suboptimal levels. Instructors often had to manually combine multiple tools to fulfill their needs, which is not ideal. There is a clear demand for better integration of these tools to enhance their interoperability. | ||

| Asfour and Alkharoubi [25] | virtual setting affordances asynchronous access | Students could utilize their time more efficiently and had a greater flexibility in online learning and teaching settings. | |

| peer learning | There was a lack of a collective design studio environment, which resulted in isolation, procrastination, and lower attention levels among students. | ||

| delivery methods and tools | The use of blended learning is a promising strategy in this regard, with the potential to enhance face-to-face design studio courses using interactive online technologies. This requires the development of course materials and specifications to accommodate this strategy, including more group assignments and teamwork. | ||

| Zairul et al. [11] | delivery methods and tools | Online technology can be used to improve studio-based learning and architecture along the blended learning spectrum. | |

| student participation | All the independent and dependent drivers for engaging students, increasing understanding, inspiring, and challenging learners remain unchanged. The current situation also demands the training of lecturers on various tools that can help to engage, challenge, stimulate. and increase the learners’ understanding. | ||

| İlter [26] | virtual setting affordances asynchronous access | ODS is endorsed for being more egalitarian by its ease of reaching resources, watching recorded lectures and critics, and presenting their work digitally both for critics and juries. | |

| feedback peer learning | The drawbacks of ODS includes a lack of peer learning and limited one-to-one student–instructor interaction. | ||

| Alhusban [27] | studio culture | It completely damaged the design studio environment and students’ social life and caused them to be lonely and challenged their well-being. | |

| student participation feedback communication | Online architectural education negatively affected the students’ design ability and skills, peer review, students’ intended learning outcomes’ (ILOs) achievements, the quality of feedback, course contents, interaction mode, and participation. | ||

| Ekici et al. [28] | communication peer learning | The students did not find distance education to be as useful as traditional design studios. This was due to a lack of social presence and the inability to share their work with peers as effectively as they could in a physical classroom. | |

| Lotfabadi and Mousavi [29] | student autonomy output media | The virtual studio offered a chance to promote independence and a research-oriented design approach. The students were proficient in digital communication techniques and had acquired the knowledge and abilities needed to be more independent. | |

| Megahed and Hassan [30] | delivery tools and methods student autonomy | The apportionments of blended learning in post-COVID-19 education will grow in a wide range of BL technologies to support the students’ development as active and self-directed learners. | |

| tutor roles | The role of the instructor changes from the teacher as teller to the teacher as curriculum facilitator. |

| Archetype | Reference ID | Findings | Mention Qty |

|---|---|---|---|

| Setting | [15,21,22,27,28] | ineffective communication | 7 |

| [15,20,21] | technical difficulties related with the digital environment | 3 | |

| [11,18,19,23] | pedagogical challenges and limits of the digital environment | 5 | |

| [15,20,24,25] | asynchronous access | 5 | |

| Actors | [15,21,27] | low level of engagement and participation | 4 |

| [16,18,20,21,29,30] | student autonomy increased | 7 | |

| [19,22,25,28] | low level of peer interaction and peer learning | 4 | |

| [18,21,30] | tutor roles need to be redefined | 3 | |

| Output | [13] | proficiency requirement in using digital tools | 1 |

| [17,25,29] | positive effect of virtual setting affordances for skill acquisition | 3 | |

| [9,21] | emphasis on digital models | 2 | |

| Dynamics | [15,16,21,26,27] | low frequency and unclear feedback | 5 |

| [15,23,26] | virtual review sessions allow participation and being student-oriented | 5 | |

| [14,15] | recordings allow for in-depth learning | 2 | |

| [17,19,24,25] | redefinition of delivery tools and methods | 5 |

| Visual | Acoustic |

|---|---|

| figure | ground |

| linear | non-linear |

| sequential | data |

| asynchronous | synchronous |

| static | dynamic |

| container | network |

| particle | field, resonance |

| Role | Process | Autonomy Level of Student |

|---|---|---|

| The master | Mimetic, focusing on the master’s practice | Tutor-centered |

| The atelier coach | Master as a teacher; one-to-one studio conversations | Dependent on the student skill |

| The reflective practitioner | Reflection-in-action; dependent on master–apprenticeship dynamic; formative | Dependent on the student skill |

| The critical friend | Reflection in and outside of the action; constructive feedback | Student-centered |

| The liminal servant | Assisting the student’s construction of knowledge; involving both the cognitive and social dimensions of learning | Student-centered |

| The analyst | Forming a mutually beneficial relationship that fosters growth and development, enabling them to eventually engage in creative play independently | Student-centered |

| Media Form | Learning Activities | Methods/Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| narrative | print/video/visual materials | apprehending |

| interactive | web sources/case analysis | exploring, investigating |

| communicative | online meetings/collaborative boards | discussing, debating |

| adaptive | skill development | experimenting |

| productive | modelling | synthesizing |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Takkeci, M.S.; Erdem, A. McLuhan’s Tetrad as a Tool to Interpret the Impact of Online Studio Education on Design Studio Pedagogy. Trends High. Educ. 2024, 3, 273-296. https://doi.org/10.3390/higheredu3020017

Takkeci MS, Erdem A. McLuhan’s Tetrad as a Tool to Interpret the Impact of Online Studio Education on Design Studio Pedagogy. Trends in Higher Education. 2024; 3(2):273-296. https://doi.org/10.3390/higheredu3020017

Chicago/Turabian StyleTakkeci, Mehmet Sarper, and Arzu Erdem. 2024. "McLuhan’s Tetrad as a Tool to Interpret the Impact of Online Studio Education on Design Studio Pedagogy" Trends in Higher Education 3, no. 2: 273-296. https://doi.org/10.3390/higheredu3020017

APA StyleTakkeci, M. S., & Erdem, A. (2024). McLuhan’s Tetrad as a Tool to Interpret the Impact of Online Studio Education on Design Studio Pedagogy. Trends in Higher Education, 3(2), 273-296. https://doi.org/10.3390/higheredu3020017