Abstract

This paper shares the research results of an explorative study investigating university lectureship experience in a Malta university context. The study aimed to obtain a holistic description of the university academic experience. The qualitative research findings, based on a thematic analysis of 10 individual interview transcripts, describe the experience of being a university academic as a journey of time passages in space and time. The journey is characterised by the strong theme of teaching along with the two other primary themes, labelled identity and un/belonging. Identity feeds on, but not only on, teaching and the sense of un/belonging. Profession/Practice and Research/Publication are two other themes that, in this study, emerge as feeding the primary themes. These research findings unsettle the privilege portrayals of tenure-track university lectureships. They confirm the emphasis on teaching in this local context and increased administration obligations. Distinctively, they expose another identity dimension in addition to the teacher and researcher attributions highlighted in the mainstream literature. These findings suggest that academics need to be supported for keeping alive differentiated identity dimensions, which are not in opposition to each other but are in competition for time. While the limitations of the study are acknowledged, several recommendations deriving from the research findings are shared.

1. Introduction

The interest in exploring university academics’ experiences is not new. Two decades ago, Åkerlind [1] explained that this research is important because of discernible shifts in the university landscape: the increasing student population, dwindling resources, and the rising expectations for improved university lectureship performance amidst resource constraints. These observations are even more significant today. Intensifying managerialism [2,3,4] and the pressure to remain current, not only as a knowledge-area expert but also in terms of showing yourself digitally competent [5,6,7,8] in a world infused by digital technologies, are now compounded. The recent COVID-19 pandemic, impacting the university lecturer experience by necessitating online teaching [9], along with intensifying demands for sustainability (United Nations, Division for Sustainable Development Goals (DSDG) https://sdgs.un.org/goals—accessed on 25 January 2024) amplifying pressures to integrate digital technologies and adopt student-centred teaching methods [10], exacerbate matters. In this changing landscape, it is all the more important to continue researching the experience of university lecturers who are key actors in shaping the higher education (HE) sector, which “has a unique position at the crossroads of education, research and innovation, serving society and economy” (European Education Area [online], https://education.ec.europa.eu/education-levels/higher-education/about-higher-education—accessed on 24 January 2024).

This research paper reports on an explorative study of university lecturers’ academic experience. The study forms part of a larger project comparing university lecturer experiences at three European universities. This paper shares the results of the Malta case. The findings of the overarching comparative research are shared in other forthcoming publications.

2. Research Background

HE specialists have long been drawing attention to the need for researching university lectureships and what it means to be a university academic from their perspective [1,11,12]. According to Teichler and Höhle [13], university academics continue to be respected as knowledge architects, creators, consultants, and disseminators. Investigating the academic profession across European universities, Teichler and Höhle [13] point to characterisations of distinction that push back on disempowering forces: (i) the long and highly selective initiation process to attain full membership as part of the academic profession, (ii) the worldwide accord fuelled by self-activism that freedom of research and self-regulation of the universities are effective strategies for achieving top-quality and relevant academic work, (iii) the academic profession as the key player in the development of the academic knowledge system and the moulding of the topmost knowledge that steers all sectors of society, and (iv) the cruciality of a close link between teaching and research to guarantee that teaching is in touch with the search for new knowledge and shaped by the most recent research developments.

Picking up on cues such as those emphasised by Giroux [14,15], who for decades, has been cautioning about increasing managerialism, control, and evaluation leading to the corporatisation of HE, several researchers (such as Juusola [2], Nixon, Scullion [16], Larsen, and Brandenburg [17]) asked questions relating to how university academics cope and succeed in teaching, research, and publication within this changing HE environment. Based on empirical research in a Finnish context, Siekkinen and Pekkola [4] claim a picture of change and continuity in academic life: change in managerial attitudes of control and evaluation and continuity in professional authority and academic identity. Smith and Plum [18] additionally emphasised that the recent global pandemic added another dimension to the terrain university lecturers navigate, which has affected their identity. To frame her research on how university lecturers manage their identity, Juusola [2] used the coping strategies framework outlined by Pache and Santos [19], consisting of compromise, avoidance, defiance, and manipulation. She reports that university lecturers are simultaneously “decoupling” and “selectively coupling” for accommodating and resisting the practices and goals of conflicting institutional logic. Additionally, Juusola [2] claims “mental decoupling” and “manifest decoupling” as a means to survive and thrive. Larsen and Brandenburg [17] draw attention to the reduced transition time early-career academics nowadays have at their disposal to resolve the identity struggle and liminality that the occupational transition brings with it. Gourlay [20] draws attention to emotional, ideological, and subjective struggles. She backs her claims with case-study research relating the story of a recruit who was alienated to the point of leaving the academy. Dickinson and Fowler [21] recounted the difficulty of shifting from being a field professional to becoming a university academic and the in-between state of being a “pracademic”. These researchers concluded that this transition is best considered as a continuum. This unearthed literature presents the academic experience of university lectureship to be from the onset a challenging, multidimensional pursuit. Benz and Bühlmann [22] also draw attention to different career trajectory varieties. They differentiate between direct careers, seniority careers, conversion careers, and parallel careers; therefore, there are different routes to entering university lectureship and to developing as a university academic. Specifically on the issue of the multidimensional nature of identity, Bennett and Hobson [23] use the metaphor of a chimaera. They refer to it as a three-headed monster comprising a lion head in terms of being a teacher, a goat head in terms of being a disciplinarian, and a serpent head in terms of being an educational researcher. Other researchers delved into the issue of how university lecturers are rising to the challenge of traversing different identities in being a university academic [11,12]. Lea and Stierer [12] foreground the changing HE landscape in considering how university academics move from one commitment task to another, while assuming different identities; they refer to “new articulations of disciplinarity” and “moving on from the golden age” as explanatory themes that describe the nature of being a university lecturer in a HE environment that is temporally and spatially changing. Generally, the literature emphasises identity struggles that change across time and space. Being a university academic demands the mind-bending task of concurrently grappling with different identities to keep up with occupational roles, responsibilities, and demands.

There is also noted in the recent HE literature an increase in critical education studies. These studies highlight exclusionary issues such as the precarity of early-career university lectureships, gender discrimination, racism, and dis/ableism [3,11,24,25,26,27,28]. Some of these studies appear to be inspired by broader societal and global events that illuminate exclusion and/or intensify social, economic, and technological issues related to “haves and have-nots” [29]. These studies emphasise that university institutions are not free from issues related to inequity, supremacy, and social injustices of different kinds. Regional and global geo-political, socio-economic, and socio-technological situations affect university lecturers’ identity, well-being, and sense of work–life balance [30]. This emergent literature presents university lectureship as an arduous experience, wherein one struggles to acclimatise, survive, and succeed in a HE environment, which is a forever-changing terrain of “super complexity” [31].

The academic literature specifically on the university lectureship experience in Malta is scarce. The comprehensive search using the HyDi search gateway and Google Scholar search portal with several keyword combinations and a snowballing technique did not yield many results. Drawing on statistical analysis of data spanning more than three decades, Baldacchino [32] claims that gender imbalance in relation to academic career progression is gradually diminishing in the concerned Malta university context. Again, within this same Malta university context, Cutajar [8] explored variations in how university lecturers experience using networked technologies for teaching. Exposed variations ranged from peripheral enhancements to seamless socio-material entanglement shaped by deepened understandings of the affordances digital technologies provide, pedagogical orientations, and teaching roles. The meagre published literature that was unearthed suggests that this study is the first exploratory, holistic investigation of the academic experience in Malta. Broadly, it adds to the emergent picture by a recent description of the university lectureship experience contextualised in a Southern European context.

3. The Study

This research is part of a wider research study comparing the experiences of university lecturers at 3 different European universities in Estonia, Finland, and Malta. Research questions asked include a comprehensive question on how university lecturers experience themselves at the university and 2 additional questions that delve deeper into the experience of being a university academic, considering teaching and research activities, relationships, and well-being. Ambitiously, the research also seeks to capture perceptions of university lecturers’ future selves and how academics construct their future academic perspectives. This research paper shares research findings from the Malta study that respond to the first question asked.

3.1. Research Context

The research was conducted at one Malta university. This is a long-established university that has traditionally emphasised its mission of serving the surrounding community and the local society at large (https://www.um.edu.mt/about/strategy/strategicgoals1learningandteaching/—accessed on 24 January 2024). It is beyond the scope of this research paper to elaborate on the HE sector in Malta, but it suffices to say that, while the local HE sector has grown substantially during the last 3 decades (including numerous local and foreign ventures offering home-grown and/or third-party certification at the diploma, undergraduate, and graduate levels), the university contextualising this research is the only local public university (https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-education-systems/malta/higher-education—accessed on 24 January 2024). Following trends in other European universities, the lectureship position at the concerned Malta university demands the doctoral award (https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-education-systems/malta/conditions-service-academic-staff-working-higher-education—accessed on 24 January 2024). Notwithstanding, there still exist cases of fulltime academic staff members who are not yet past the doctorate level and so hold temporary assistant lectureship positions. The concerned university has a policy in place so that fulltime academic staff who are reading doctoral studies are assigned fewer teaching duties. Since 2017, there is also established at the concerned university a doctoral school for supporting staff and students in their early-career research pursuits. Furthermore, in recent years, a dedicated academic development unit for supporting university lecturers in teaching as well has been evolving. At this university, the academic lectureship career consists of 4 ladder grades, in the following order: Lecturer, Senior Lecturer, Associate Professor, and Professor. Promotion criteria include teaching quality, research output, and commitment to the university, the academic profession, the surrounding communities, and society at large. It is up to the university academic to apply for a promotion after they assess themselves as worthy of the desired grade. A promotion committee evaluates and decides whether applications for promotion are deemed to have met the relevant criteria.

3.2. Research Methods

Considered on its own, this Malta study is a small-scale research investigation of a case. An interpretative approach within the qualitative paradigm was assumed for conducting the study cases. For the Malta study, this research approach led to a rich dataset and the configuration of a comprehensive description of what university lectureship in the concerned local context stands for. Participant recruitment started in early 2023, after obtaining a research ethics clearance from the University Research Ethics Committee and the permission of the University Rector to conduct research at the given university. The university administration assisted by circulating an email among academic staff members inviting research participation.

3.3. Research Sample

The resulting research sample includes 10 participants. It covers 5 of 14 faculties and 1 of 16 additional interdisciplinary institutes of the university. All recruited participants turned out to be fulltime university academic staff members. The participants held different occupational grades in the professorial and lecturer bands. Two participants were at different stages of reading doctoral studies. Table 1 shares participants’ demographic data. Broad terms are used to indicate the disciplinary area participants located themselves. More demographic details could not be shared without risking the identification of participants considering the small Malta context.

Table 1.

Partial demographic data tabulation of research participants.

Data collection took the form of individual, in-depth interviews of 60–75 min with consenting participants held online. Interviewees were prompted to talk about their teaching, research, and academic life at the university, including future academic projections. At the entry prompt, interviewees were invited to talk about themselves as a university academic and what brought them into the university lectureship career: “Please tell me about yourself” and “How did you become a university academic?” Prompts and supplementary questions for opening up the conversation were kept as neutral as possible, providing space for interviewees to talk about their experiences as university academics. For example, the prompt used to channel the conversation on teaching was as follows: “Who and what do you teach?” and “What does teaching mean to you?” The planned prompt to encourage interviewees to talk about their research was as follows: “Tell me about your research”. Prompt questions were skipped when interviewees spontaneously talked about issues. The first interview and another interview on request by the participant were conducted by the research author, who is also an academic staff member at the concerned university and known to some of the research participants. The rest of the interviews were conducted by a research officer purposely recruited to assist in the data collection and first-level data analysis as agreed with the international research partners. The research assistance is deemed to have worked well to also address the research author’s dual role as an insider and a researcher, in addition to the vigilant reflective mood intended to keep in check personal biases and to maintain an open-minded perspective to the alternative views, perspectives, and understandings that were being shared by the participants. The audio-recorded interviews were transcribed using an online automation service and cleaned by the research author.

The data analysis followed the thematic analysis methods outlined by Braun and Clarke [33]. The first level of analysis consisted of the 3 three steps: (i) familiarisation with the data, (ii) data coding, and (iii) code categorisation, generating themes and subthemes. Qualitative data analysis software and subsequently an electronic spreadsheet application were used to manage the data coding, the categorisation of themes and subthemes, and keeping track of illustrative transcript excerpts. For this first level of data analysis, systematically sifting through the data to identify a preliminary set of themes and subthemes, the research author worked alongside the research assistant, familiarising herself with the dataset of interview transcripts, listening to the recordings, coding a transcript to help confirm coding consistency, and independently deriving themes and subthemes serving to cross-check codes, emergent themes, and subthemes. These efforts were intended to build the internal validity and reliability of data analysis processes. The research author followed up with another 3 steps: (iv) reviewing and revising initial themes and subthemes, (v) refining and finalising the set of themes and subthemes, creating thematic network mappings, and (vi) writing narrative descriptions answering the several research questions asked. Each distinct step incorporated several iterations sifting through the unabridged transcripts. All research results were backed by quotations from the transcripts, but in publication, it is not always possible to share substantiating information without risking participant identification.

4. Research Findings

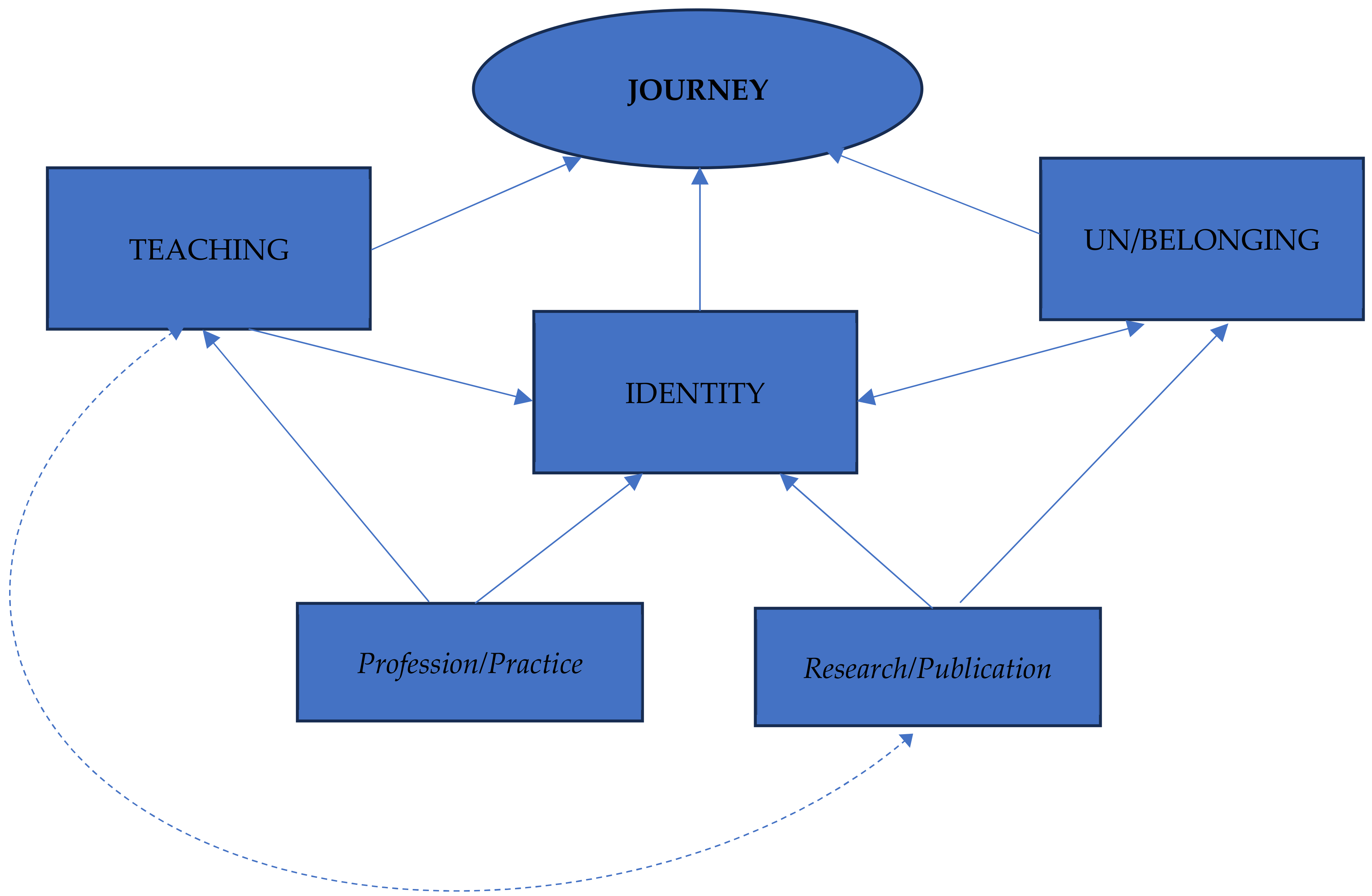

The overarching conceptualisation describing how university lecturers experience themselves at the university emerges from this research as what one might refer to as a JOURNEY of multiple parallel, divergent, and convergent passages in space and time. Figure 1 shares a graphical representation of the thematic description of university lectureship. The JOURNEY is constituted by three primary themes: TEACHING, IDENTITY, and UN/BELONGING. These three core aspects describing how university lecturers experience themselves are not mutually independent. The theme IDENTITY is shaped by TEACHING and UN/BELONGING along with the subthemes Research/Publication and Profession/Practice. These subthemes also feed into the primary themes of UN/BELONGING and TEACHING. The thematic pairs IDENTITY and UN/BELONGING, and TEACHING and research/publication, are configured from this dataset as supporting each other to different degrees, hence the two-way arrow connector in Figure 1 and the use of the dotted line for what appears to be a less pronounced link.

Figure 1.

Thematic description of university lectureship.

4.1. Journey

The transient nature of the university lecturer experience arises through the discerning consideration of being in time—past, present, future: (i) for being a teacher, (ii) for developing a multifaceted identity responding to the demands of being an expert in different academic practice roles within the university, while remaining visible and credible as a professional practitioner outside the university, and (iii) for achieving a sense of belonging within the university academic community by developing a voice and being heard, while building connections across the academy and professional bodies outside the university realm. The term professional practitioner is used in this writing as a generic term for referring to the referenced professional occupations, such as being a lawyer, teacher, and so forth.

4.2. The Quest for Tenure

A preliminary passage shaping the journey is the quest leading to tenured university lectureship. Except for a participant who started as a researcher and later shifted into a university lectureship position, which might be considered as a direct route to university lectureship [22], all participants referred to their accumulated experience in professional practice before moving into fulltime university lectureship. A total of 8 of 10 research participants spoke about a preliminary commitment to casual visiting lectureship before eventually applying and securing a fulltime lectureship position that matched their interests and knowledge specialisation area. A participant recounted a story of disappointment from committing to a heavy teaching workload as a visiting lecturer for many years. According to this participant, the story would have continued were it not for the high-risk action of abruptly withdrawing from all visiting lectureship commitments. As Himmelsbach [34] remarks on the university lectureship experience, there is no guarantee that the effort of committing to casual academic work will eventually lead to a tenured lectureship position. Notwithstanding, this study suggests that the most common and strategic route to follow for securing a tenured university lectureship is to first commit to a visiting lectureship.

4.3. The Doctorate

Before, during, or after the passage of securing tenure, there is the doctoral journey. As noted and captured in the research sample of this study, at the concerned university, it is possible to find academic staff members reading for their first doctorate. This milestone was fleetingly considered by participants who completed the doctorate before moving into a fulltime lectureship. Those who read for the doctorate while in a fulltime lectureship position talked about delays, restarts, isolation, relational power tensions, and extensive teaching assignments hampering them from finding the time to work on their doctoral research. Teaching demands are identified as making it very hard to avoid the doctoral journey dragging on for years.

The four participants who talked about these experiences (happening in the present or the past) confessed that their teaching demands are/were so excessive that they cannot/could not avail themselves of the concession permitting them a reduced teaching load. A participant recounted how their doctorate dragged on for nearly a decade because of extensive teaching demands. Another participant recounted being forced to postpone doctoral studies for years until a senior colleague in the same department completed their doctorate because of teaching demands. One participant confessed that it was by accident that she found out about the policy and her entitlement. As for the case of the other participants, the request for a reduced workload was not accepted because of teaching exigencies. A participant who was not yet past the doctorate at the time of the interview divulged that all weekends had to be sacrificed because there was no time for doctoral studies during the work week. Another participant talked about the multiple times the doctoral research theme had to be changed because of multiple supervisor changeovers and discipline territoriality. These participants’ confessions directly or indirectly reveal the relational power tensions in play. From the accounts of the research participants, teaching demands and an element of power influence are clearly obstacles that slow down doctoral research if this work is pursued concurrently with a fulltime university lectureship. These findings echo Bowyer et al.’s (2022) arguments that while strategies and policies may be in place, one cannot assume that their promises are being fulfilled.

4.4. The Struggle of Juggling Academic Work Obligations

All research participants described difficulties in keeping up with the extensive workload. The time-consuming teaching assignments were pinpointed as hindering research engagement by all participants of this research study. Participants elaborated on how teaching demands at the university leave them with hardly any time to pursue research and publication. T14 shared an elaborate personal story to illustrate how teaching and administration work is leaving him no time to complete a research project that started years ago. Recent recruits T8 and T16 claimed that they are spending a lot of time learning about procedures, regulations, and unwritten organisational culture. T8 specifically referred to the first years of fulltime university lectureship as a time of enculturation in terms of learning how things work: “All the information is out there, [on the institutional website] … every day, I encounter new things that I didn’t know and I learned. And that’s the journey, I suppose at the moment” (T8).

T8 also dwelled on the hierarchical organisational structure as well as the autonomy of university lectureship. He maintained that things work differently in the private sector, where he used to work as a professional practitioner before moving into a fulltime university lectureship. T9 and T12 explicitly referred to the three work obligations of a university lectureship, including teaching, research, and administration. T2, T11, T12, and T14 called attention to the overwhelming amount of administration work. A participant commented on the overwhelming amount of administration work that fulltime lectureship brings with it:

“To be honest, I’ve barely had the time to touch two papers to read apart from those I need to prepare my lectures because there’s a lot of administration work to do. It’s crazy. I never thought it would be like this, you know. I thought when I’d be a lecturer, I would have time to research. But in actual fact, I don’t really have time”(T11)

T2 highlighted how more administration work was being piled on academics, leaving them less time to pursue research. Generally, the participants’ accounts suggest that university lecturers spend a lot of time on administration tasks. From this dataset, it can be seen that university lectureship work obligations are highly demanding. Prompted and unprompted, all the research participants pointed out teaching, student research supervision, the provision of student support beyond the lecture rooms, doing research, and engaging in writing and publication as part of their work obligations at the university. But they also talked about remaining active in professional practice outside the university. Half of the participants, coming from all the discipline areas covered by this study, talked about the need to remain active and visible as a professional practitioner outside the university. T1, T2, and T15 also emphasised participation in community outreach for teaching the community beyond the university. While sharing a lot of detail on their efforts participating in community outreach, T1 and T2 lamented the lack of academic recognition for this academic effort. T1 and T11 commented on the invisible time one spends providing students with “pastoral care” outside the obligatory class time. Participants described numerous stories of how, one way or another, they go beyond the counted academic effort of their work at the university. T9, T12, and T14, who did not share stories of community outreach, disclosed that they are extensively engaged in administration and managerial work within the university. Reflecting on the many years of university lectureship, T9 commented that the three distinct work obligations compel the university lecturer to become an all-rounder: “[they are] opportunities to grow … like, an academic becomes a bit of an all-rounder” (T9). It was reasoned that these work obligations serve as a means for well-being as well: “It stresses me when I feel a bit overwhelmed with this volume, you know. But generally, I have a sense of well-being, and as we said, as I said before, the fact that we change what we’re doing … It’s a bit of research, a bit of admin, and a bit of teaching. There’s a lot of variety” (T9).

The different work commitments, concurrently advancing multiple identity pursuits, summon a picture of parallel, overlapping, and entangled passages in time and space. There is no denying that university lectureship brings with it a lot of work. But, looking at it retrospectively, the multidimensional passages in space and time potentially turn out to be a means of self-fulfilment.

4.5. Teaching

The teaching commitment is by far the most prominently talked about work obligation in these participants’ accounts, confirming that it occupies these university lecturers’ minds and time most pervasively. All participants commented on their enjoyment of teaching, some more expressively than others. T1, T2, and T3 remarked multiple times on their passion for teaching: “I enjoy teaching” (T1, T3); “As I already told you, I enjoy teaching” (T1); “I do see myself as a natural teacher” (T3); “I always wanted to teach … the mission of teaching was always there” (T2). All research participants claimed some degree of teaching experience before eventually moving to fulltime lectureship, at least in the form of a visiting lectureship commitment prior to tenure.

Coming from the Education discipline, T9 and T11 acknowledged their expertise in pedagogical knowledge by way of their profession, but generally, those employed to teach at the university are assumed to know how to teach irrespective of their background:

“I find it ridiculous frankly that at universities, people who hold a PhD are expected to know exactly how to teach”(T8)

Several times this same participant referred to the academic development course he was obliged to commit to when he recently shifted to a fulltime lectureship. This disclosure concurrently revealed that the concerned university is taking steps to change this. Prompted by an interview question, all research participants critically reflected on their teaching. They highlighted their personal efforts to move away from the traditional lecture form of information dissemination. A total of 7 of 10 participants (T8, T9, T11, T12, T14, T15, T16) described alternative dialogic-, experiential-, and/or inquiry-based pedagogical methods. T8, T9, T12, and T15 also shared how, after the COVID-19 pandemic experiences of remote teaching and social distancing, they are now incorporating digital technologies to enhance face-to-face teaching and reaching out to students and supporting them by using digital channels and media. Interestingly, when prompted to consider well-being at the university, participants talked about the care and welfare of students and students’ learning, completely overlooking the issue of self-care and personal well-being.

Participants noted that fulltime university lectureship forced them to turn their focus almost exclusively to teaching. From these participants’ accounts, it appears that Bennett and Hobson’s [23] lion-head chimaera in terms of being a teacher is the dominant head. Some participants were apologetic about their disproportionate focus on teaching to the point of neglecting their research and publication pursuits. T14 remarked on the negative impact this has on one’s career as an academic because professorial grades are heavily dependent on one’s research and publication record. In the participants’ accounts, what Juusola [2] describes as “manifest decoupling” for surviving the demands of teaching is suggested. The substantial preoccupation with teaching commitments appears to be consuming the university lecturer’s time, limiting their possibilities to engage in research and publication pursuits.

4.6. Identity

In this study, IDENTITY is constituted as another primary theme shaping the overarching concept of a JOURNEY. All participants to some degree reflected on the multifaceted nature of identity in being a university lecturer. Teaching is one of the several roles a university lectureship obliges, even if, as shared in the previous subsection, the participants of this study prioritise teaching and hence the cultivation of their identity as university teachers. T9 and T14 explicitly talked about assuming multiple identities that distinguish between the teacher role and the professional practitioner role they perform in the community outside the university. T9 argued that these different identities are not in opposition to each other but complement and inform each other. This participant also elaborated on the teaching and administration commitments making it impossible to keep alive the commitment to the professional practice commitment in industry and community services. T14 affirmed that he finds it so crucial that he also encourages colleagues to keep practising their profession in the services industry, alongside their fulltime university lectureships. T1, T15, and T16 also elaborated on the importance of remaining visibly active, as otherwise, you lose your credibility as a knowledge expert with students and other professional practitioners in the community. In Malta’s small island context, keeping alive your identity as a professional practitioner in the community outside the university appears, from these participants’ accounts, as significant also for fulfilling the role of being a credible university academic. T2 and T16 spontaneously talked about themselves as researchers and elaborated on their researcher roles in an integrative way in relation to being university academics. T2 described himself as a researcher, while concurrently expressing his long-standing passion for teaching. He talks about the need for established university academics to support early-career researchers and colleagues in continuing the legacy of the knowledge area. T16 turned her attention to the tremendous effort needed to keep up her research and publication commitment and to collaborate with international peers while maintaining the teaching commitment of being a fulltime university lecturer. T11, T14, and T15 confessed that they have research and publication work in progress, but they hardly find time for it, exposing the struggle to keep their researcher identities alive. The remaining half of the research participants confessed that they had to put their research on hold. Some of these participants (T3, T8, T12) suggested that student research supervision is a form of research commitment. T3 even mused regarding publication co-authorship with students. Although there was no explicit articulation of the researcher’s identity with respect to the case of being a university teacher and being a professional practitioner outside academia, there is an acknowledgement of the researcher’s role in being a university academic alongside the teacher role. Notably, although the research participants commented on the substantial administrative tasks they were expected to complete, there was little or no personal identification with the administrative role. As aforementioned, T9 reflected on the obligatory administration duties and managerial roles one is obliged to take up in being a fulltime university lecturer, only vaguely linking the university academic identity to administration and management roles. Two participants specifically spoke about their involvement in university governance, and they did not, directly or indirectly, identify themselves as being administrators or managers but kept projecting themselves as university academics in a collegial relationship with other university lecturers. Overarchingly, these findings agree with literature findings on university lecturers’ claiming identity fragmentation (Barnett, 2000; Henkel, 2005). They expose the university lectureship identity as fluid and explainable by the changing combination and blend of distinct roles the academic assumes, feeding the configuration of identity [35]. As the university lecturer navigates different assignments, commitments, and missions, progressing through the journey of being a university academic, the discernment of the different roles and identities of selfhood appears to shift and deepen. Distinctively, these findings reveal the “pracademic” identity fragmentation of being a university teacher and professional practitioner, along with a restrained researcher identity overshadowed by a dominant teacher identity.

4.7. UN/Belonging

UN/BELONGING is configured as another primary theme of the overarching JOURNEY. It refers to the sense of belonging and unbelonging of being part of the university academic staff community. The theme emerges as a strong one across the dataset even if only 3 of 10 participants (T1, T2, T9) expressly spoke of the “university community”. T2 several times declared that the university is “one whole family”. A total of 6 of 10 participants emphasised that their connection to the university dates back to their undergraduate student years as young adults. These participants shared stories of the interim period as graduates spending time pursuing further studies and/or professional practice before returning to the university as lecturers. One of these participants proudly declared that his connection to the university had continued almost unbroken for decades. Another participant declared that it felt like “home” returning to the university as a lecturer after some years of studying abroad. The dataset exposes a sense of pride and satisfaction with respect to being part of the university academic staff that at times is observed as spurring introspection and critical questioning of self-worth and personal identity: “I still suffer from the impostor syndrome. So sometimes I feel I shouldn’t be there” (attribution intentionally withheld). T8 and T16, who are affiliated with different faculties, applauded faculty-wide meetings, which they pinpointed as a means to become acquainted with what is happening and their faculty colleagues. Widening the field of view, T16 also elaborated on the rectorate as that mysterious place where rules and regulations are devised and handed down to the faculties and staff to follow. The inner circle of community membership is emphasised, in terms of deciding rules and regulations on how the community works and for those situated in the periphery to follow. From this research sample, few participants (T9, T12, T14) projected themselves as well integrated into their membership in terms of being part of the university academic staff community. Nevertheless, one of these participants stressed multiple times that he would walk away the minute he was no longer happy on the job.

A well-established participant shared a story of isolation from the rest of the university staff community and its resources. Another participant spoke about disconnection from academic colleagues, who for many years before the COVID-19 pandemic, had held back from inviting her to join departmental research enterprises and accommodate her in teaching pursuits because of a lack of vision in terms of seeing the possibilities of digital technologies and their communicative capabilities in terms of assisting with workarounds in difficult life situations. The same participant also dwelled on the possibility of a career change as a way to solve the problem of an overwhelming university lectureship workload. The dataset is peppered with comments that overtly or subtly project a sense of marginalisation and unbelonging as much as there is exhibited a sense of pride and satisfaction in belonging to the university academic staff community. The sense of belonging and unbelonging in being part of the university community surfaces as a passage of rethinking connectedness, feeding into the other primary theme of identity in terms of being a university academic, and overarchingly, the journey of being a university academic in the space of time.

4.8. Profession/Practice and Research/Publication

The subtheme Profession/Practice incorporates the notion of being knowledgeable about the profession and being competent as a practitioner in the profession. Research participants spoke about professional practice experiences in considering the issue of professional knowledge. Directly or indirectly, all research participants talked about the need to keep relating to professional practice. Half of the participants explicitly emphasised that it is a crucial issue to continue being active in professional practice circles and/or practising the profession in order to preserve one’s credibility with students and other professionals in the field of practice.

This attention to professional practice links up to the concerned university’s declared mission of preparing the next generation of professional practitioners to serve the needs of the community at large. These comments call to mind the concerned university’s mission as well as the pracademia orientation [36]. Similar to Dickinson and Fowler’s [21] participants, some of the research participants of this study appear to reside in the liminal space, grappling with the different identities of being a professional practitioner and a university academic, as discussed above in considering the IDENTITY theme. T12 confessed that, at one point, it was impossible to keep on practising the profession because of the teaching workload and the additional administration and managerial responsibilities he signed up for. He had to choose to put his professional practice commitments on hold, while participating more actively in university governance and management alongside his teaching commitment.

The subtheme RESEARCH/PUBLICATION denotes the university lecturer’s commitment to engaging in research and publication. Participants referred to writing for publication as a form of research, hence the combined RESEARCH/PUBLICATION label. A participant distinguished between two types of research in fulfilling academic work: research in relation to teaching and teaching preparation (including the periodic updating of learning materials and the exploration of new teaching methods) and research taking the form of investigative work for which one would seek to secure funding. Interestingly, most of the participants understood research and publication to be of this latter type, not necessarily linked to funding but, from their disclosures, implicitly associated with their occupational identity as a university academic. It was this observation that led this research author to configure this subtheme as feeding into the primary theme of IDENTITY.

As aforementioned, many of the participants had to be explicitly prompted to speak about their research commitment, even if later it turned out that some had research and publication work in progress. Extensive teaching schedules, resulting in a lack of time, appear to be the main reason. Those who are reading doctoral studies are even more stressed to find time for completing their doctoral research. The suggestion that emerged from the participants’ accounts, as discussed above, regarding the idea of postgraduate student research supervision and the possibility of publication in co-authorship with students, may be a way to up the game of university lecturers when it comes to research and publication.

5. Discussion

These findings expose university lecturers experiencing themselves on a journey of passages denoted by the strong preoccupation with teaching and the pursuit of other identity facets in trying to be a university lecturer, a worthy member of the university academic community, and a credible expert within the broader community. From the research participants’ accounts of this study, it appears that extensive teaching and administration obligations are hampering university lecturers in their research and publication pursuits and, in turn, compromising their academic career progression. Those who commit to fulltime university lectureships while reading for their doctorate are badly affected, as this may drag on for many years. This research also exposed the distinctive pressure to remain active as a professional practitioner in the community in order to safeguard one’s credibility as a field expert. University lectureship is presented as the challenging pursuit of different identities, wherein personal well-being is overlooked and work–life balance is not part of the equation. To cope, university lecturers focus on teaching, giving up on research/publication pursuits or professional/practical activism, if not both when the teaching and administration demands become too extensive. The findings reveal traces of alienation, but generally, to date, it is still more likely for one to persevere rather than opt for a career change, as reported to be happening in other international contexts [20,37]. A university lectureship, viewed from the inside, does not look so much like the privileged occupation it is seen to be from the outside; from the outside perspective, it would seem that one would have the time to pursue the disciplinary knowledge one is passionate about. While a sense of accomplishment in being part of the university academic staff community prevails, community membership also surfaces as more like enculturation in becoming assimilated into the system. For university academics who are critically reflective of their university lectureship positioning in divergence from others and how the system functions, there is a sense of unbelonging along with a sense of belonging.

5.1. Implications and Recommendations

These research findings are preliminary results of a small, exploratory study. They open a very small window onto the landscape of the university lectureship experience in a Malta university context. They permit a limited view of the terrain but nevertheless convey several implications and recommendations. The concerned university is already providing support through an academic development course for new recruits, but early-career academics still struggle to achieve a balance of roles. Possibly, new recruits are supported by consenting to senior university academics acting as mentors. Fulltime university lecturers who are reading doctoral studies need to be supported in practical terms. An existing policy entitling them to a reduced teaching assignment is in place, but this needs to be expressly communicated and implemented by those who are responsible for teaching assignments. The picture of extensive teaching and administration work impeding the pursuit of research and publication is creating what appears to be a conflict situation. The university is setting forth criteria for academic career progression (in terms of professorial grades) tied to research and publication, but at the same time, it is hampering university lecturers from achieving them. Perhaps, promotion criteria for career advancement also need to be revised for giving due credit to alternative academic work commitments in terms of professional practice and community outreach as well. At an individual stakeholder level, one solution surfacing from this research is the idea of postgraduate student research supervision being recognised as a university lecturer’s research endeavour too, with the possibility to take this even further with student co-authorships of research publications. The study findings also suggest that there is a need to push back against the undercurrent of individualism, territoriality, and competition within disciplinary knowledge areas to create a culture of collaboration. Apart from the critical retrospective mood that these findings call forth, a recommendation deriving from the participants’ accounts in this study is the creation of more spaces, places, and opportunities for university academics to meet and network, helping to build social and collegial relationships. While there are initiatives within faculties to bring the academic staff together, more frequent events for university academics within faculties and across the university are needed. Potentially, such initiatives also serve all involved to achieve more belonging and dampen unbelonging, potentially prompting a sense of well-being.

The implications of these research findings and derived recommendations are especially important for informing local stakeholders. There are the university academics themselves, especially those who are new to university lectureships and those who continue to struggle in trying to understand the university academic trajectory. The holistic description of being a university academic achieved by this research potentially helps bring some clarity and possibly inspire personal trajectories to take positive constructive directions. The research outcomes potentially also serve the administration and managerial staff of the concerned local university and others in the wider community in terms of improving university lectureship support. These research findings potentially also serve to inform university funders and boost their confidence in continuing to support it and invest in it.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

A more extensive study is needed to extend the findings of this small-scale study to obtain a more detailed picture of the Malta university lectureship experience. These findings are based on the accounts of 10 fulltime university lecturers who only partially cover the range of the faculties, institutes, and schools of the concerned university. Furthermore, the accounts are transcripts of one-time, individual interviews with those who responded to the call for research participants. The self-selecting participant recruitment procedure may have factored in a bias (Sharma, 2017), considering that the dataset is representative of those who were willing to participate and came forward to have their voices heard. There may be numerous other views, issues, and concerns still hidden from view.

There was a directed effort to build internal reliability and validity of the research as it unfolded. However, the possibility of bias finding its way into these interpretative findings can never be fully excluded. The identified limitations do not reduce the value of the research results achieved, but they do highlight that they present a limited partial picture.

More research is needed to create a more representative picture of the given Malta university case. In consideration of the whole Malta HE area, the study is also limited because of its focus on a single Malta university context. This research prompts further research pursuits that bring in a greater number of research participants, participants who cover the whole range of disciplinary areas, and a participant sample representative of the university lectureship population at the given university, at other Malta university institutions, and across the Malta HE context.

6. Conclusions

The research findings of this exploratory study on a Malta case offer a first glimpse into the local university lectureship holistic experience. They add to the academic literature corpus focusing on the university lectureship experience with a recent description of a Malta context. Distinctively, they expose university academics in this local context prioritising teaching in trying to keep up with institutional demands, hence drastically slowing down research pursuits, if not also completely stalling them. The findings of this study portray the university lectureship experience in a given Malta context as a challenging journey of parallel, overlapping, and entwined passages stretching across space and time in terms of navigating different identities and struggling to become a worthy member of the university academic staff community, while at the same time, being visibly credible as a professional practitioner active in the surrounding community. Perhaps, the biggest takeaway from this research is the need for a more collective and discerning reflective and reflexive mood, nurturing a culture of empathic mutual peer support, wherein everyone matters, potentially striving to become a visibly credible community of academics inside and out.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Tallinn University grant number TA/4719.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee) of the University of Malta (protocol code EDUC-2022-00687 approved on 11 January 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the research assistance of Dr Pen Lister.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Åkerlind, G. Academic growth and development—How do university academics experience it? High. Educ. 2005, 50, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juusola, K. Coping with managerialism: Academics’ responses to conflicting institutional logics in business schools. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2023, 17, 89–107. [Google Scholar]

- Si, J. No other choices but involution: Understanding Chinese young academics in the tenure track system. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2023, 45, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siekkinen, T.; Pekkola, E.; Carvalho, T. Change and continuity in the academic profession: Finnish universities as living labs. High. Educ. 2019, 79, 533–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markauskaite, L.; Carvalho, L.; Fawns, T. The role of teachers in a sustainable university: From digital competencies to postdigital capabilities. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2023, 71, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markauskaite, L.; Marrone, R.; Poquet, O.; Knight, S.; Martinez-Maldonado, R.; Howard, S.; Tondeur, J.; De Laat, M.; Buckingham Shum, S.; Gasevic, D.; et al. Rethinking the entwinement between artificial intelligence and human learning: What capabilities do learners need for a world with AI? Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 2022, 3, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryberg, T.; Davidsen, J.; Bernhard, J.; Larsen, M.C. Ecotones: A Conceptual Contribution to Postdigital Thinking. Postdigital Sci. Educ. 2021, 3, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutajar, M. Higher Education Teachers’ Experiences of Networked Technologies for Teaching; Educational Research Monograph Series; Borg, C., Ed.; Malta University Publishing: Msida, Malta, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hodges, C.; Moore, S.; Lockee, B.B.; Trust, T.; Bond, M.A. The Difference between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. Educ. Rev. 2020, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Hashim, M.A.M.; Tlemsani, I.; Matthews, R.D. A sustainable University: Digital Transformation and Beyond. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 8961–8996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, L. Younger academics’ constructions of ‘authenticity’, ‘success’ and professional identity. Stud. High. Educ. 2008, 33, 385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lea, M.R.; Stierer, B. Changing academic identities in changing academic workplaces: Learning from academics’ everyday professional writing practices. Teach. High. Educ. 2011, 16, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichler, U.; Höhle, E.A. The academic profession in 12 European countries–the approach of the comparative study. In The Work Situation of the Academic Profession in Europe: Findings of a Survey in Twelve Countries; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, H. Neoliberalism, Corporate Culture, and the Promise of Higher Education: The University as a Democratic Public Sphere. Harv. Educ. Rev. 2002, 72, 425–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroux, H. Democracy in crisis, the specter of authoritarianism, and the future of higher education. J. Crit. Scholarsh. High. Educ. Stud. Aff. 2015, 1, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon, E.; Scullion, R.; Hearn, R. Her majesty the student: Marketised higher education and the narcissistic (dis)satisfactions of the student-consumer. Stud. High. Educ. 2018, 43, 927–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, E.; Brandenburg, R. Navigating the neo-academy: Experiences of liminality and identity construction among early career researchers at one Australian regional university. Aust. Educ. Res. 2023, 50, 1069–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Plum, K.; Taylor-Smith, E.; Fabian, K. An exploration of academic identity through the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2022, 46, 1290–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, A.-C.; Santos, F.M. Inside the Hybrid Organization: An Organizational Level View of Responses to Conflicting Institutional Demands; IDEAS Working Paper Series from RePEc; ESSEC Research Center: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gourlay, L. ‘I’d landed on the moon’: A new lecturer leaves the academy. Teach. High. Educ. 2011, 16, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickinson, J.; Fowler, A.; Griffiths, T.-L. Pracademics? Exploring transitions and professional identities in higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 2022, 47, 290–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benz, P.; Bühlmann, F.; Mach, A. The transformation of professors’ careers: Standardization, hybridization, and acceleration? High. Educ. 2021, 81, 967–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.; Hobson, J.; Jones, A.; Martin-Lynch, P.; Scutt, C.; Strehlow, K.; Veitch, S. Being chimaera: A monstrous identity for SoTL academics. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2016, 35, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, K.A. Constructions of success in academia: An early career perspective. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 743–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorn, I.; Seelmeyer, U. Inquiry-Based Learning about Technologies in Social Work Education AU—Zorn, Isabel. J. Technol. Hum. Serv. 2017, 35, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortlieb, R.; Weiss, S. What makes academic careers less insecure? The role of individual-level antecedents. High. Educ. 2018, 76, 571–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, D. The Access Compromise and the 5th R. An Open Eductional Reader; EdTech: Carmel, IN, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hollywood, A.; McCarthy, D.; Spencely, C.; Winstone, N. ‘Overwhelmed at first’: The experience of career development in early career academics. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2020, 44, 998–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, L.; Eynon, R. Digital Divides and Social Justice in Technology-Enhanced Learning. In Technology Enhanced Learning: Research Themes; Duval, E., Sharples, M., Sutherland, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 157–168. [Google Scholar]

- Bowyer, D.M.; Hodgson, H.M.; Hamilton, M.; James, A.; Allen, L. Mid-Career Challenges in Australian Universities: A Collaborative Auto-Ethnographic Narrative, in Women in Higher Education and the Journey to Mid-Career: Challenges and Opportunities; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 168–200. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, R. University knowledge in an age of supercomplexity. High. Educ. 2000, 40, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldacchino, G. Origins and Destinations: The Career Paths of Male and Female Academics at the University of Malta; Malta Chamber of Scientists: Msida, Malta, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himmelsbach, V. How to Become a Tenure Track Professor. In TOP HAT; Tophatmonocle Corp: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Balaban, C.; de Jong, S.P. Academic identity at the intersection of global scientific communities and national science policies: Societal impact in the UK and Netherlands. Stud. High. Educ. 2023, 48, 941–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollweck, T.; Netolicky, D.M.; Campbell, P. Defining and exploring pracademia: Identity, community, and engagement. J. Prof. Cap. Community 2022, 7, 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, B. Academia Next: The Futures of Higher Education; John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).