Abstract

Teacher professional well-being (TPWB) is crucial in education, affecting educators and students. The Teacher Professional Well-Being Scale (TPWBS) measures five core dimensions—self-efficacy, job satisfaction, aspiration, recognition, and authority—initially developed in Turkey. This study aims to adapt, develop, and validate the Teacher Professional Well-Being Scale (TPWBS) in Ethiopia. Investigate the TPWBS factor structure and evaluate its measurement invariance (MI) across gender, university type, and teaching experience. By examining teachers’ perceptions of professional well-being, this study contributes to understanding Ethiopian higher education. Exploratory factor analyses (EFA) and confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) use data from Ethiopian university instructors. Conduct initial EFA on a sample of 82 men and 222 women (sample 1), followed by CFA on a sample of 529 men and 179 women (sample 2). Assess factor loadings of TPWBS items across sub-dimensions. Use data from Ethiopian higher education institutions and involve 1012 instructors. The EFA reveals excellent factor loadings for all TPWBS items within each sub-dimension, indicating a robust factor structure. TPWBS exhibits acceptable construct validity, good reliability, and satisfactory convergent and divergent validity. The CFA demonstrates good model fit, supporting TPWBS validity: χ2 (289) = 942.20, p < 0.001, χ2/df = 3.26, GFI = 0.912, TLI = 0.935, CFI = 0.943, RMSEA = 0.057, 95% CI [0.053, 0.061]. TPWBS is a valid and reliable tool for assessing the professional well-being of Ethiopian university teachers. Its adaptation and validation process highlight cultural and contextual factors in well-being evaluation. Findings offer insights for practitioners and researchers in well-being assessment.

1. Introduction

Teacher well-being is a crucial issue in the field of psychology and education, as it directly impacts student learning and teacher professionalism [1,2]. Teachers’ professional well-being (TPWB) forms the foundation of the teaching and learning process [1,2], significantly influencing students’ social, emotional, physical, and academic development [3]. TPWB refers to an individual’s overall perception of their professional capacities [1]. It encompasses various aspects of teachers’ work-related behavior, including job satisfaction, motivation, commitment, and experiences of stress and burnout [4]. Teachers with high levels of professional well-being are more likely to be satisfied in their jobs and engage in effective teaching practices [5]. They are motivated, engaged, emotionally invested in their work, and employ effective instructional strategies, leading to improved student learning [6]. Furthermore, high levels of professional well-being enable teachers to exhibit positive instructional behaviors, such as passion, interest, and enthusiasm, which positively influence the classroom atmosphere [7]. Teachers’ professional well-being also influences their emotional and social interactions with students [5]. Teachers with higher professional well-being are better equipped to foster positive student–teacher relationships, creating a supportive learning environment [8]. They feel supported by colleagues and principals, experience greater self-efficacy, less work pressure, and adopt a more student-centered approach [5]. Moreover, when teachers feel comfortable in their professional environment, they invest time and effort in their professional growth, leading to quality classroom instruction [9]. Conversely, teachers with lower levels of professional well-being are more likely to experience stress and burnout [10]. Stressful working environments negatively affect teachers’ motivation, self-efficacy, and job commitment, thereby impacting the educational system and students’ learning outcomes [5]. Burned-out teachers create harmful learning environments associated with negative student outcomes [11]. Lower levels of TPWB manifest in burnout, exhaustion, lower work commitment, lack of concentration, and psychosomatic complaints, adversely affecting teachers’ professional practice [10]. Understanding the concept of teachers’ professional well-being and its determining factors is essential for designing effective intervention strategies in the educational context [7]. Analyzing professional well-being in different cultural contexts is crucial for comprehensive school interventions [1]. However, there is no standardized measure available for assessing professional well-being and guiding the well-being of university instructors globally. Therefore, this study aims to validate the TPWBS developed by [1] in the context of Ethiopian higher educational settings, considering the African collectivist culture.

The justifications for studying teachers’ professional well-being are manifold. Firstly, well-being is a complex and multifaceted construct in psychology, necessitating the development of a valid and reliable instrument to study, assess, and promote instructors’ professional well-being, given the many different sources and factors contributing to well-being [12,13,14]. Therefore, it is crucial to develop a single, valid measure specifically designed for assessing professional well-being. To this end, we focus on exploring the cross-cultural applicability of TPWBS, which assesses multiple theoretical domains of well-being.

Secondly, TPWBS, developed by [1], has been validated in the Turkish cultural context, confirming a three-factor model of teacher professional well-being while recommending further exploration of the authority and aspiration domain in different cultural settings. However, no Ethiopian studies have examined the validity of TPWBS, and no studies have investigated this topic in other cultural contexts.

Thirdly, previous studies have evaluated the psychometric properties of TPWBS in the Turkish cultural context [1]. The study employed both qualitative and quantitative analyses, confirming the factors using a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). However, the proposed five-factor structure of TPWBS was not well-supported in the Turkish context, indicating a need for further investigation. Moreover, there have been no studies validating TPWBS with university instructors or employing measurement invariance across different cultural settings. Additionally, there is a lack of research on the psychometric properties of TPWBS in the Amharic language or an African cultural context. Thus, this research aims to examine the Ethiopian Amharic version of TPWBS, evaluating factorial validity through exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis, as well as convergent, divergent, and discriminant validity. We hypothesized that the five-factor structure of TPWBS found in previous studies [1] would need to be positively correlated with measures of emotional intelligence [15], life satisfaction [16], and psychological capital [17] and negatively correlated with [18] for the convergent and divergent validity purpose to ensure the external validity of TPWB. It also explores measurement invariance across different demographic groups and examines the reliability of the scale.

1.1. Measures of Teachers’ Professional Well-Being

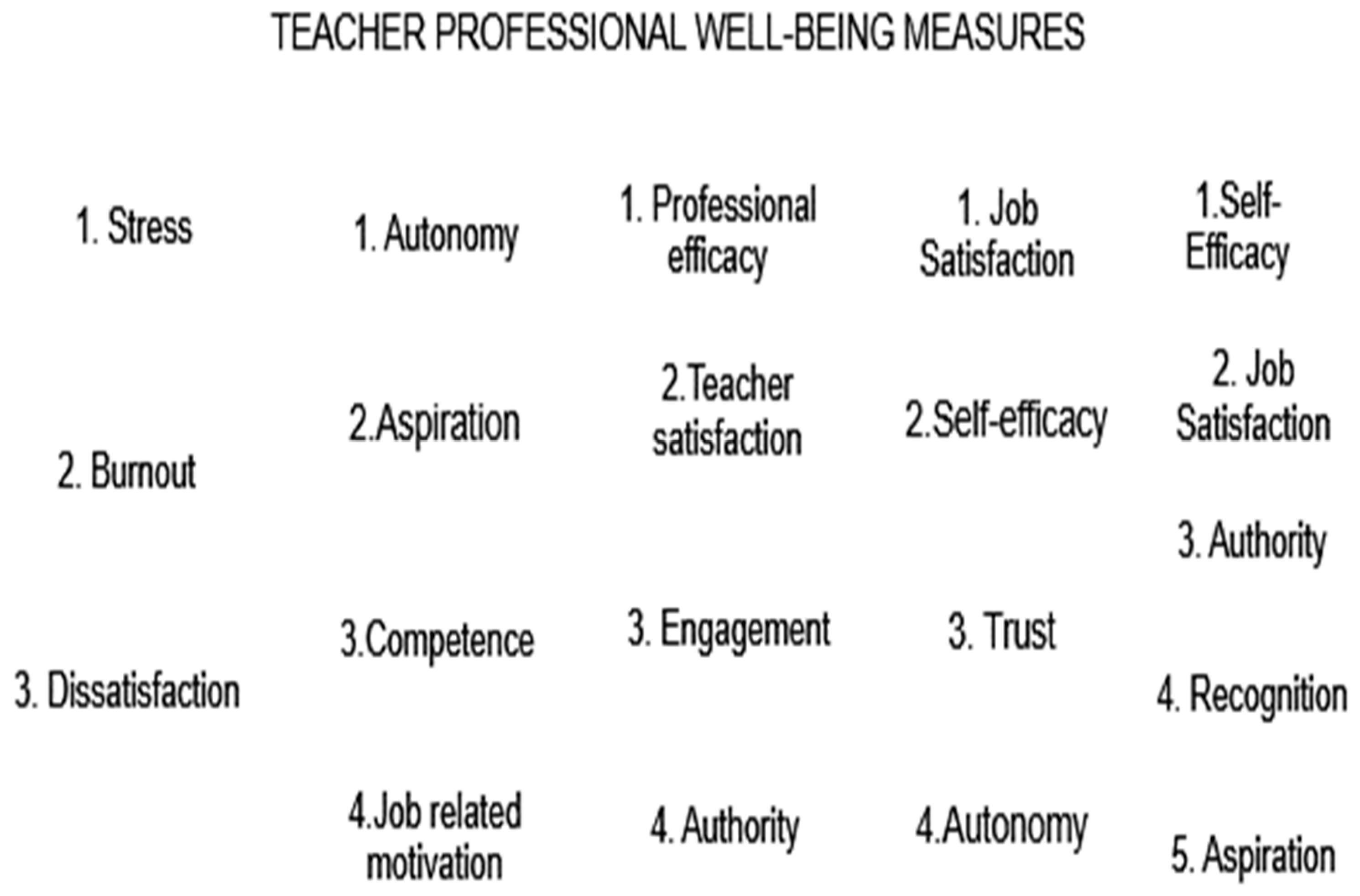

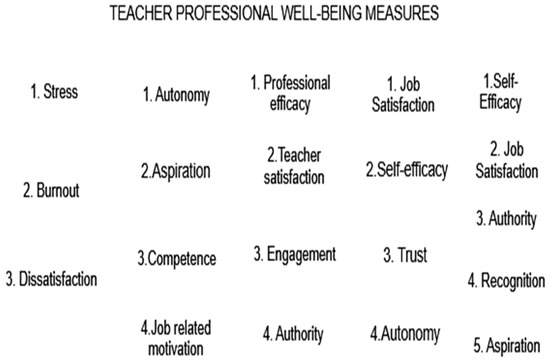

Teachers’ professional well-being is a complex construct that encompasses various dimensions and is influenced by cultural contexts. Measuring this construct accurately is crucial for designing effective intervention strategies and understanding the unique challenges faced by teachers. Several researchers have proposed different models and measurement tools to assess TPWB [7,10,19]. A study by [10] developed a measurement tool for teachers’ professional well-being, which included three scales: aspiration, competence, and autonomy. These scales were used to measure the dimensions of professional well-being among Dutch teachers. The authors reported factor loadings ranging from 0.59 to 0.70 and reliability scores between 0.74 and 0.86 for the subscales. Research by [7] assessed teachers’ professional well-being using a survey with 54 statements in the context of Russian settings. The survey covered aspects such as autonomy, self-acceptance, professional goals, competence, positive relationships, and professional growth. However, the authors did not provide detailed information about the psychometric properties of the survey instrument. A study by [1] proposed a more comprehensive model of teachers’ professional well-being, which included five core dimensions: self-efficacy, job satisfaction, recognition, aspiration, and authority. The author conducted exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses and found that recognition, self-efficacy, and job satisfaction were valid and reliable measures of professional well-being, while aspiration and authority were not as significant. The author recommended further studies to investigate the dimensions of authority and aspiration in different cultural contexts.

To address the limitations of existing measures, [1] developed the TPWBS in Turkish cultural settings. This scale consists of 26 items that assess self-efficacy, job satisfaction, recognition, authority, and aspiration. It is based on the framework of positive psychology and has been validated in previous studies. Ratings are made on a scale from 1 (“very strongly disagree”) to 7 (“very strongly agree”), with a possible score range of 26 to 154. The TPWBS has been recommended for use in other languages and cultural settings, with all five dimensions included, to enhance the applicability and comprehensibility of the measure. An intensive study conducted by [1,20] suggested that the core components of the currently used model should be derived from positive psychology; the study is the most cited in the literature. Although, measuring the concept is still a problematic issue [1,8,10,20]. In the literature, various teacher professional well-being models are compared (see Figure 1); however, [1]’s model is the most comprehensive and sound measure for further investigation. Also, the TPWBS has been highly recommended to explore in other languages and cultural settings using the five dimensions rather than the three to increase the applicability and comprehensibility of the measure [1]. In conclusion, measuring teachers’ professional well-being is a complex task due to its multidimensional nature and cultural influences. The TPWBS developed by [1] provides a comprehensive and validated measurement tool that can be used to assess different dimensions of professional well-being in teachers. Further research is needed to explore and adapt this measure in various cultural contexts and languages.

Figure 1.

Teacher professional well-being measures related to the current study. Note: The above measurement sources are found in the following references [1,2,7,10,19].

1.2. Socio-Demographic Factors and TPWB

Socio-demographic factors have long been studied in relation to teachers’ professional well-being, and numerous researchers have explored their influence on TPWB. Among these factors, gender, work experience, and the type of school where teachers are employed have received particular attention [1,20,21,22,23]. When examining the impact of gender on TPWB, researchers have yielded inconsistent findings. Some studies have reported that female teachers exhibit higher levels of professional well-being compared to male teachers, while others have found no significant differences between the genders [1,20,24,25,26]. These conflicting results highlight the complexity of the relationship between gender and professional well-being, which may be influenced by cultural contexts, societal norms, and organizational dynamics. Therefore, further research is necessary to gain a better understanding of how gender interacts with teachers’ professional well-being, considering the specific contexts and variables at play.

Similarly, the influence of work experience on TPWB has produced mixed results. Some studies suggest that younger teachers experience higher levels of professional well-being compared to more experienced teachers, while others have found that teachers with more years of experience report higher levels of well-being [1,20,27,28]. The relationship between work experience and TPWB appears to be complex and warrants further investigation to comprehend the role it plays in shaping teachers’ well-being.

In addition to gender, work experience, and the type of school where teachers are employed can significantly impact their professional well-being [28]. Schools play a crucial role in shaping teachers’ experiences and, consequently, their well-being. Factors such as institutional support, rules, and regulations within schools can have a substantial influence on teachers’ professional well-being and overall development. Therefore, it is essential to comprehend the influence of the school level on TPWB to create supportive environments that promote the well-being of educators.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

The current study employed a quantitative research design with an associational and cross-sectional approach, deemed well-suited to achieve the stated objectives.

2.2. Study Setting

The study was conducted in the Amhara Regional State of Ethiopia, specifically targeting undergraduate students enrolled in public universities within the region.

2.3. Population and Sample

The exploratory factor analyses (EFA) and confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) use data from Ethiopian university instructors. We have divided the data into two groups to conduct the EFA at the initial stage on a sample of 82 men and 222 women (sample 1), followed by the CFA on a sample of 529 men and 179 women (sample 2). We used data from Ethiopian higher education institutions and involved 1012 instructors. The sample for this study included 708 university instructors, of which 529 (74.7%) were men and 179 (25.3%) were women. The participants were selected from public universities in the Amhara Regional State of Ethiopia. However, due to missing information or data entry mistakes, 21 participants from the second group were excluded, resulting in an effective response rate of 95.8%. The final sample of the CFA or study 2 consisted of 529 male public university instructors (74.7%) and 179 female instructors (25.3%). The mean age of the participants was 32.68 (SD = 6.21) years. The sample included participants from different types of universities, with 227 (32.1%) from research universities (Gondar), 191 (27.0%) from applied universities (Wollo University), and 290 (41.0%) from comprehensive universities (Debre-Tabor University). The sample size was determined based on established guidelines, aiming for a statistically stable estimate and minimizing sampling errors [29].

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Target Measure

Teacher Professional Well-Being Scale (TPWBS). The TPWBS (see Appendix A and File S1) was used to measure professional well-being, which was conceptualized to have the following five core dimensions: (i) self-efficacy, measured with seven items (e.g., “I have knowledge and skills to carry out my profession adequately”); (ii) job satisfaction, with six items (e.g., “Students in this class take care to create a pleasant learning environment”); (iii) recognition, with four items (e.g., “I receive appreciations because of my professional achievement”); (iv) authority, with five items (e.g., “I have productive talks with the school administrators on professional issues”); and (v) aspiration, with four items (e.g., “I always have enthusiasm for doing professionally new things”). Each item scored using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = very strongly disagree–7 = very strongly agree) and exhibited satisfactory construct validity and good internal consistency. In a previous study, the TPWBS was found to have acceptable reliability, with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from authority to recognition in the range of 0.65 to 0.81. The four sub-scales were acceptable, except for the authority sub-scale, which needed further psychometric investigation [1].

2.4.2. Criterion Measures

Emotional Intelligence Scale (EIS-16). Emotional intelligence (EI) was assessed using the 16-item EIS-16 [30], based on the Salovey and Mayer EI framework [31]. The EIS-16 consists of four dimensions: self-emotional appraisal (SEA), others’ emotional appraisal (OEA), use of emotions (UOE), and regulation of emotions (ROE). Respondents rated each item on a 7-point Likert scale. The scale demonstrated acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) and construct validity in this study.

Psychological Capital Questionnaire (PCQ-24). The PCQ-24, developed by [32], measures positive psychological resources. It consists of four subscales: hope (α = 0.80, 0.72, 0.75, 0.76); self-efficacy (α = 0.84, 0.75, 0.85, 0.75); optimism (0.76, 0.74, 0.69, 0.79); and resilience (α = 0.71, 0.66, 0.71, 0.72). Each subscale includes six items, and respondents rate their agreement on a 6-point Likert scale. The PCQ-24 has been previously validated in various cultural and linguistic contexts, including Ethiopia; for example, in Ethiopia [33], Lithuania [34], South Africa [35], France [36], and Brazil [37]. The scale demonstrated good reliability and validity in the Amharic version used in this study.

Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS). The SWLS, developed by [38,39], is a widely used instrument for measuring global life satisfaction. The scale consists of five items rated on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The SWLS was translated and validated in the Ethiopian context, exhibiting good psychometric properties, including reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) [16]. In present study, the Cronbach’s alpha reliability of the scale was α = 0.858.

Job Burnout. The Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI): Teacher burnout was assessed using the MBI developed by [40]. The MBI consists of 22 items that reflect emotional exhaustion (EE), personal accomplishment (PA), and depersonalization (DP). Respondents rate items on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (every day). The MBI has been translated and validated in the Ethiopian context, demonstrating good reliability and construct validity [18]. The MBI had excellent reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.801), and the subscales, i.e., EE, PA, and DP, were α = 0.935, 0.939, and 0.834, respectively, in this study.

2.5. Procedures

2.5.1. Ethics of the Study

The ethical aspects of a scientific study are of utmost importance, and this research study obtained ethical approval from the institutional review board of Wollo University (Ref. No. 128/2021, provided on 12 October 2021). Prior to their participation, all individuals involved willingly provided their informed consent. Moreover, this research study adhered meticulously to the prescribed protocols, guidelines, and regulations outlined in the international code of research ethics. By ensuring compliance with these ethical standards, this study demonstrated its commitment to upholding the rights and well-being of the participants.

2.5.2. Adaption, Translation, and Validation of the TPWBS

To ensure the adaptation, translation, and validation of the TPWBS (Teacher Professional Well-Being Scale) for use in a different cultural context, the following steps were taken, following the guideline of [41,42]: (a) Translation: The TPWBS was translated from its original language (presumably English) into the Ethiopian Amharic language. This translation was carried out by a bilingual expert at a university and a professor of psychology. These translators were chosen for their expertise in both languages and their extensive experience in teaching and research. (b) Content Knowledge Check: The translators ensured that the content of the TPWBS was accurately translated by checking for content knowledge. This step aimed to verify that the translated version captured the intended meaning and concepts of the original scale. (c) Back-Translation Procedure: Following the initial translation, a back-translation procedure was conducted. This involved translating the Amharic version of the TPWBS back into English. The purpose of this step was to assess the accuracy and fidelity of the translation by comparing it to the original English version. (d) Accuracy Testing: The accuracy of the translated content was assessed by comparing the back-translated English version with the original English version of the TPWBS. Any discrepancies or inconsistencies were identified and addressed to ensure the translated version reflected the intended meaning of the scale. (e) Questionnaire Administration: Once the translation and accuracy testing were completed, the translated TPWBS questionnaires were administered to the Ethiopian university teachers. This step allowed for the evaluation of the questionnaire’s comprehensibility, clarity, and relevance within the target cultural context. By following these steps, the adaptation, translation, and validation process of the TPWBS for use in the Ethiopian Amharic language was organized and carried out effectively.

2.6. Data Analysis

In order to test this study’s hypotheses, we employed IBM SPSS version 29.0 and Smart PLS 4.1.0.3 for conducting the statistical analysis.

2.6.1. Reliability

To assess the reliability of each PERMA profiler sub-scale and total well-being, we employed Cronbach’s alpha (α), Omega reliability, and the composite reliability (CR) coefficient. These measures are widely used indicators of internal consistency. According to the evidence, the obtained reliability values were considered acceptable [43,44,45].

2.6.2. Convergent, Divergent, and Discriminant Validity

To evaluate construct validity, convergent validity (positive associations with similar constructs) and divergent validity (negative or non-correlations with opposite constructs) were examined by analyzing Pearson’s correlations between TPWBS scores and other theoretically relevant outcomes. The standard cut-points for correlational coefficients proposed by [46] were utilized. These cut-points define negligible correlations (ranging from 0.00 to 0.10), weak correlations (0.10 to 0.39), moderate correlations (0.40 to 0.69), strong correlations (0.70 to 0.89), and very strong correlations (0.90 to 1.00).

The convergent validity was assessed by examining the correlations between TPWBS scores and measures of self-reported emotional intelligence, psychological capital, life satisfaction, and job burnout. The divergent validity was evaluated by examining the correlations with constructs that are theoretically opposite or unrelated. Additionally, the convergent and discriminant validity were assessed using two measures: Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and Maximum Shared Variance (MSV). AVE values higher than 0.5 indicate good convergent validity. Furthermore, constructs with an AVE higher than their MSV demonstrate good discriminant validity [44].

2.6.3. Factorial Analysis

The researchers employed a comprehensive approach to assess the construct validity of the TPWBS [1], utilizing both exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis techniques. To investigate the exploratory factor analysis, robust maximum likelihood for factor extraction was employed in conjunction with varimax rotation, applying Kaiser normalization. In evaluating the adequacy of sampling, the researchers referred to the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure, for which [47] suggested the following thresholds: excellent (≥0.90), very good (0.80–0.89), acceptable or moderate (0.70–0.79), mediocre or average (0.60–0.69), miserable or inadequate (0.50–0.59), and unacceptable (≤0.50).

To further examine the structure of the TPWBS, confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted based on the five proposed models presented by [1]. In evaluating the fit of these models, the researchers decided not to rely solely on the chi-square test (χ2) due to its sensitivity to sample size, as recommended by [48,49]. Instead, they employed widely reported goodness-of-fit indices, including the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA).

For the RMSEA, the following thresholds were applied: poor fit (>0.10), mediocre fit (0.08 to 0.10), good fit (0.05 to 0.08), close fit (0.01 to 0.05), and exact fit (0.00), following the guidelines proposed by [50]. In the case of groups consisting of 10 to 20 participants, [50] suggested an RMSEA threshold of ≤0.08 for acceptable fit. As for the TLI and CFI, the recommended thresholds were as follows: poor fit (>0.85), mediocre fit (0.85–0.90), acceptable fit (0.90–0.95), close fit (0.95–0.99), and exact fit (1.00), according to [50]. In addition to the goodness-of-fit indices, information criteria, such as the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC), were deemed appropriate for model comparison and selection, as suggested by [51]. Furthermore, the utilization of these statistics reliably requires a sample size of at least 200 participants, as indicated by [51].

2.6.4. Measurement Invariance (MI)

In our study, we conducted tests to assess the measurement invariance of the TPWBS across various demographic variables, namely gender (women and men), university types (research, applied, and general universities), and experience in teaching (below 5 years, between 6 and 10 years, and 11 years or above). We employed the best fitting model obtained from the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) as the baseline model for the measurement invariance analysis. To ensure that the factor structure and loadings of the TPWBS were equivalent across different groups, we examined four levels of measurement invariance: configural, metric, scalar, and residual. Configural invariance tests whether the same factor structure holds across the groups, while metric invariance examines whether the factor loadings are equivalent. Scalar invariance assesses the equivalence of both factor loadings and item intercepts, and residual invariance examines the equivalence of residual variances across groups.

In accordance with the recommendations of [52,53], we employed single and multi-group CFA to test for the configural, metric, scalar, and residual invariances. To determine the adequacy of measurement invariance, we used the following criteria: a ΔTLI (change in Tucker–Lewis index) of 0 representing perfect invariance, and a ΔTLI of ≤0.01 indicating acceptable invariance. For the metric, scalar, and residual invariance, we employed a ΔRMSEA (change in root mean square error of approximation) of 0.015, as suggested by [54,55]. By conducting these measurement invariance tests, we aimed to ensure that the TPWBS measurement model is consistent and comparable across different groups, allowing for valid and meaningful comparisons of scores between individuals from different genders, university types, and teaching experience categories.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics, Normality Distributions of the Study Variables

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for the constructs, including the minimum and maximum values, means, and standard deviations. Additionally, it provides information on the normality of distribution by examining the kurtosis and skewness of the data.

Table 1.

Min, Max, Means, SD, Kurt, and Skew for the Teacher Professional Well-Being.

3.2. Factor Structure

Bartlett’s test of sphericity yielded a significant result (χ2(325) = 5442.554, p < 0.001), indicating that the factor analytic model was suitable for this study. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy, which assesses the appropriateness of factor analysis, indicated a moderate value of 0.846 for this study. Furthermore, the analysis revealed that 72.616% of the variance was accounted for, suggesting that the relationships among the variables were moderate and acceptable. Notably, all 26 items exhibited eigenvalues greater than 1.00, signifying their relevance and contribution to the factor analysis (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Exploratory Factor Analysis of the Five-Factor TPWBS Solution (n = 304).

3.3. Reliability and Validity

Evidence of the Main Variables in the initial phase of our research, we conducted a thorough assessment of the construct validity, construct reliability, and internal consistency of the variables used within the context of higher education in Ethiopia. Our aim was to ensure the reliability and validity of the measurements employed in our study. We followed established guidelines to determine the reliability of the variables, where scores above 0.90 indicate high reliability, scores between 0.80 and 0.90 suggest good reliability, and scores between 0.70 and 0.80 indicate adequate reliability [44].We carefully evaluated the validity and reliability of the TPWB dimensions and present the results in Table 2 and Table 3. The TPWB construct exhibited high reliability with an alpha coefficient of 0.91 and a CR value of 0.92. Additionally, self-efficacy demonstrated good reliability with an alpha coefficient of 0.84 and a CR value of 0.86. Job satisfaction exhibited high reliability with an alpha coefficient of 0.88 and a CR value of 0.88. Similarly, recognition and authority demonstrated high reliability with an alpha coefficient of 0.88, 0.89 and a CR value of 0.88, 0.90, respectively. Lastly, aspiration displayed high reliability with an alpha coefficient of 0.91 and a CR value of 0.91. These findings establish the high reliability of the TPWB construct’s four components and the five key core elements within Ethiopia’s educational system.

Table 3.

Reliability and Validity Indices of the Study Variables (N = 708).

To evaluate the construct validity of these variables, we assessed both their discriminant and convergent validity utilizing the TPWBS [1]. Table 3 presents the AVE, MVE, and CR values for the subcomponents of the study variables. Our analysis revealed that all the five dimensions of TPWBS demonstrated good convergent validity, as their AVE values exceeded 0.05. This indicates that the respective items comprising these constructs are composed of fundamental components that exhibit reasonable correlations.Discriminant validity of the TPWBS was examined using two different techniques. Firstly, we assessed the constructs based on their AVE values in comparison to their MSV values (Table 3. Specifically, the sub-constructs of the TPWBS, including aspiration (AVE = 0.71 > MSV = 0.60), self-efficacy (AVE = 0.58 > MSV = 0.08), job satisfaction (AVE = 0.71 > MSV = 0.10), recognition (AVE = 0.64 > MSV = 0.10), and authority (AVE = 0.64 > MSV = 0.60), exhibited acceptable discriminant and convergent validity within this study.

Secondly, we assessed discriminant validity by comparing the AVE with the squared inter-item correlations within each construct [44].The AVE values for all sub-constructs exceeded the squared correlations for each construct, indicating that the corresponding items, which primarily loaded on each factor, better explained the variance for each component (refer to Table 3). Besides, we have tested TPWBS with positive constructs such as life satisfaction, emotional intelligence, and psychological capital to assess convergent validity, and with a negative construct (burnout) to evaluate discriminant validity (see Table 4). Consequently, the TPWB constructs fulfill the standards for both convergent and discriminant validity within the Ethiopian higher education context. These outcomes also imply that the measurement instruments utilized are appropriate for assessing teacher professional well-being in the Ethiopian higher education context.By conducting a comprehensive assessment of construct validity and reliability, we have ensured that our measurement instruments accurately capture the dimensions of TPWB and the key core elements within the Ethiopian higher education system. This rigorous approach strengthens the credibility and robustness of our research findings, enhancing the overall scientific rigor of our study.

Table 4.

Convergent and Divergent Validity Indices of the Study Variables.

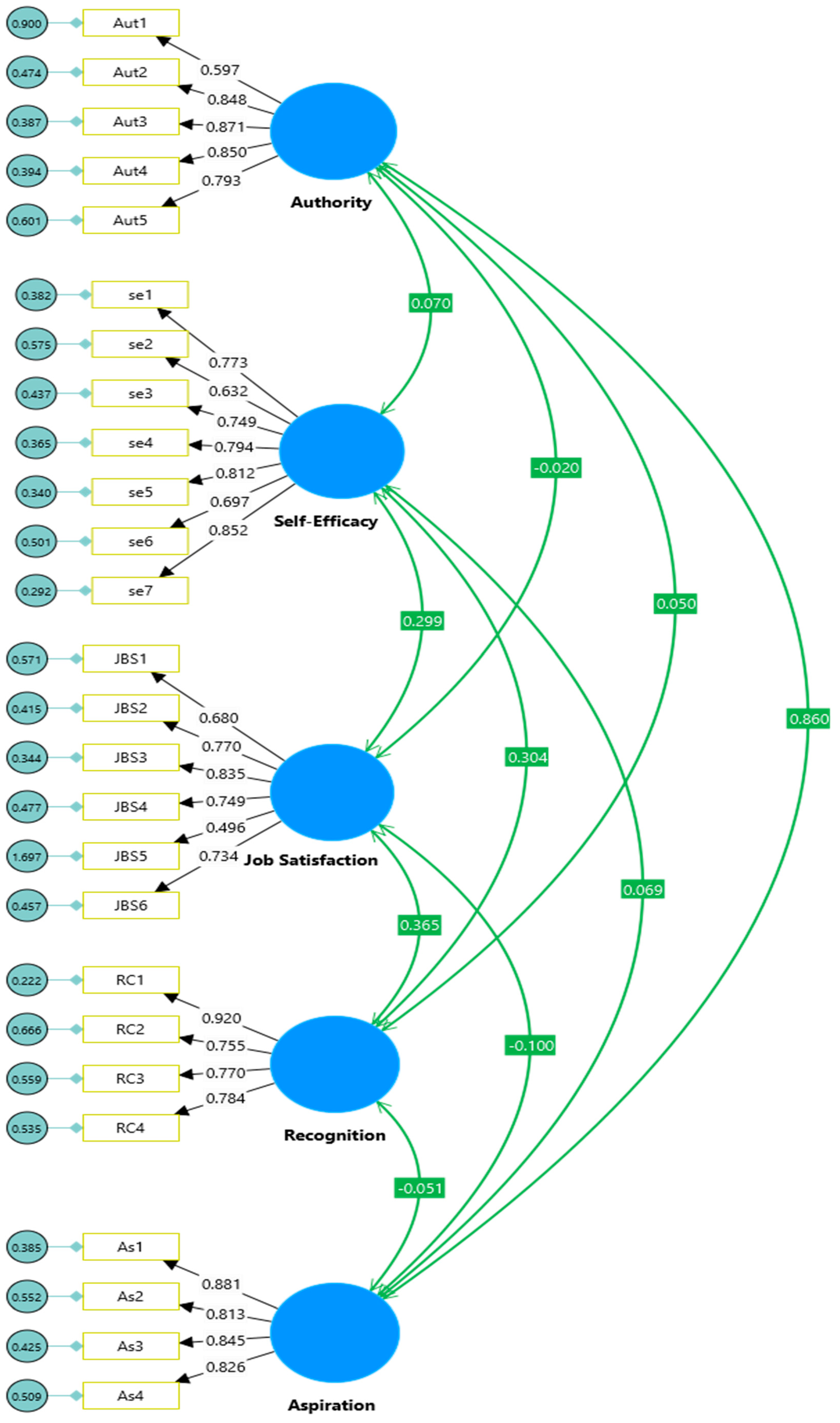

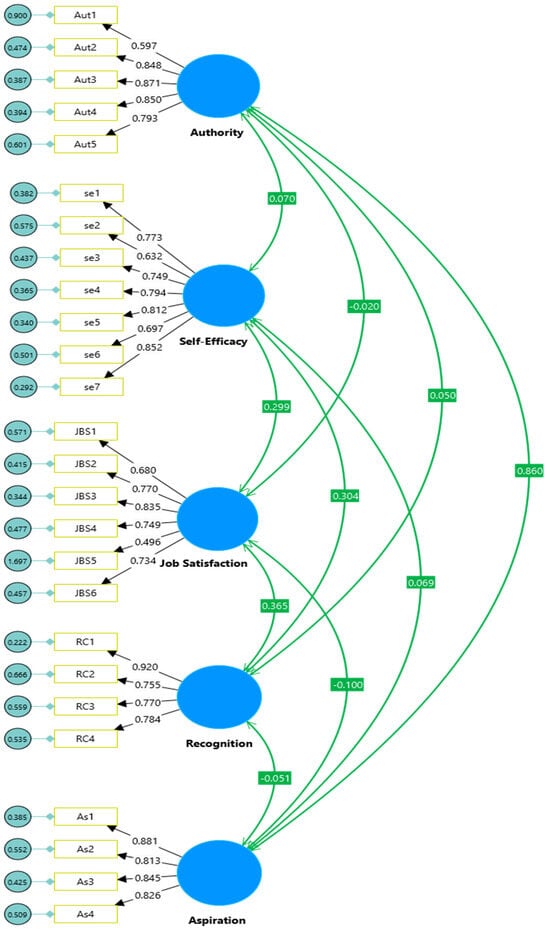

3.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) of the Five Factor TPWBS

The construct validity of the TPWBS and its relationship with criterion variables, namely life satisfaction, job burnout, emotional intelligence, and psychological capital, was assessed using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) (see Table 4). Table 5 presents the results of the CFA for the five-factor model of the TPWBS found that, χ2 (289) = 942.19, p < 0.00, χ2/df = 3.26, TLI = 0.935, CFI = 0.943, RMSEA = 0.057, 95% CI [0.053, 0.0614] (See Figure 2). The fit indices indicate a reasonably good fit of the model to the data. The chi-square test (χ2) shows a significant result (χ2 (289) = 942.19, p < 0.001), suggesting that there are differences between the model and the observed data. However, it is important to note that the chi-square test is sensitive to sample size and may not be the most suitable indicator of model fit [44]. To account for this, other fit indices were considered. The chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio (χ2/df) is within an acceptable range (3.26), indicating a relatively good fit. The Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and comparative fit index (CFI) values of 0.935 and 0.943, respectively, surpass the recommended threshold of 0.90, indicating a satisfactory fit. The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) value of 0.057 (with a 95% confidence interval [0.053, 0.0614]) is also within an acceptable range, suggesting a reasonable fit of the model.

Table 5.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) for the Target and Criterion Measures in this Data (N = 708).

Figure 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis of the five-factor model of TPWBS.

Turning to the criterion variables, a correlated factor model was employed. The fit indices for each criterion variable model indicate good to acceptable fit. The chi-square test results for life satisfaction, emotional intelligence, psychological capital, and job burnout are χ2 (5) = 10.645, p = 0.590, χ2 (98) = 410.56, p < 0.001, χ2 (246) = 1281.13, p < 0.001, and χ2 (206) = 1183.14, p < 0.001, respectively. The chi-square to degrees of freedom ratios (χ2/df) for all criterion variables are within acceptable ranges, ranging from 2.13 to 5.21. The TLI and CFI values range from 0.903 to 0.992 and from 0.914 to 0.996, respectively, indicating good to excellent fit for the models. The RMSEA values range from 0.040 to 0.079, with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals indicating reasonable fit for the models.

Overall, the results of the CFA indicate that the five-factor model of the TPWBS and the correlated factor models of the criterion variables demonstrate acceptable to good fit to the data. These findings provide support for the construct validity of the TPWBS and its relationships with life satisfaction, job burnout, emotional intelligence, and psychological capital within the context of our study.

3.5. Measurement Invariance (MI)

In a four-step process of testing MI, more strict equality constraints were specified for model parameters between or among groups (for example, men vs. women; research universities vs. applied universities vs. a general university; experience in teaching: 5 years or below vs. 6–10 years vs. 11 and above years) within a multiple-group CFA (MGCFA) following the guidelines of [16,39,53,55].

The configural model served as a starting point for subsequent tests and did not impose any equality constraints on parameters in the initial stage [56]. Configurational invariance holds that comparable groups (same gender, university type, and experience in teaching) should exhibit the same underlying factor structure. The metric model then looked at how similar the factor loadings were across groups for each item. Valid group comparisons require invariant factor loadings [56]. Following this, the scalar model looked for evidence of equal item intercepts, referring to the assessment of whether mean differences at the item and factor levels can completely equal one another’s variances. Finally, the rigorous model, or residual invariance, was used as the last step to determine whether the variances of each item’s regression equations were equal across groups [53]. We established that at least three fit indices (the TLI, CFI, or RMSEA) had to meet the predetermined cut-points for a model’s fit to be adequate. The cut criteria for changes in model fit indices were 0.10 for the CFI and TLI and 0.15 for the RMSEA [56]. The findings of this study on the TPWB by gender, university type, and experience in teaching were, therefore, interpreted using a TLI and CFI threshold of points ΔCFI = 0.02 and of ΔRMSEA = 0.03 for the RMSEA [53].

Gender. The single-level measurement model for teacher professional well-being (TPWB) demonstrated acceptable fit for both women (χ2(289) = 497.77, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.910, TLI = 0.920, RMSEA = 0.064) and men (χ2(289) = 825.70, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.934, TLI = 0.941, RMSEA = 0.059). This indicates that the model accurately captured the measurement of TPWB for both genders. Subsequently, measurement invariance (MI) testing was conducted to assess the equivalence of the TPWB model across gender. In the first step, the configural measurement invariance (CMI) model was examined, which showed the best fit with TLI = 0.928, CFI = 0.936, and RMSEA = 0.043. This suggests that the overall structure of the TPWB model was similar between genders.

Moving on to the second step, the metric measurement invariance (MMI) was assessed based on the fit of the CMI model. The results of the maximum likelihood test indicated minimal differences, with values of ΔTLI = −0.002, ΔCFI = −0.001, and ΔRMSEA = 0.001. This suggests that the TPWB model exhibited metric invariance, meaning that the relationships between the observed variables and latent constructs were comparable across genders. Furthermore, the scalar invariance and residual invariance were evaluated across gender. The values obtained for the TPWB were ΔTLI = −0.002, 0.013, ΔCFI = 0.001, 0.010, and ΔRMSEA = 0.000, −0.00, respectively. These findings indicate that TPWB demonstrated scalar and residual invariance across gender, indicating that the measurement of all variables within the TPWB model was equivalent regardless of gender. In conclusion, based on these analyses, we can affirm that the TPWB model exhibited measurement equivalence across genders, indicating that it accurately measured TPWB for both women and men.

University Classification. The analysis conducted on the five-factor-correlated TPWBS model provided an acceptable fit to the data when considering different university types, namely research, applied, and comprehensive universities. This was evident at the single-factor level, as indicated by the goodness-of-fit indices. For the research universities, the model demonstrated a conventionally acceptable fit to the data, as evidenced by the chi-square statistic (χ2(287) = 530.549, p < 0.001), TLI = 0.924, CFI = 0.933, and RMSEA = 0.061 [0.053–0.069]. Similarly, the applied universities also showed an acceptable fit, with a chi-square statistic (χ2(284) = 581.68, p < 0.001), TLI = 0.901, CFI = 0.910, and RMSEA = 0.074 [0.066–0.083]. The comprehensive universities exhibited a satisfactory fit as well, with a chi-square statistic (χ2(287) = 550.84, p < 0.001), TLI = 0.940, CFI = 0.947, and RMSEA = 0.056 [0.049–0.063]. The configural measurement invariance (MI) was examined to assess the consistency of the TPWB construct across different university types, and the results were considered conventionally acceptable, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Fit Indices for Measurement Invariance (Configural, Metric, Scalar, and Residual) Models Across Socio-demographic factors.

The subsequent step involved conducting measurement invariance (MI) testing by demanding that the factor loadings remain constant across levels, meaning that the within-factor loadings are equal to the between-factor loadings for all items. The overall model fit for TPWBS remained adequate, with a ΔCFI = −0.001 and ΔRMSEA = 0.000, indicating that the TPWB construct maintained sufficient consistency across university types. Further analysis involved performing MI testing by requiring that factor loadings be constant across university classifications (types), again assessing the within-factor and between-factor loadings. The metric invariance of the values of ΔTLI = −0.003, ΔCFI = 0.001, and ΔRMSEA = 0.000 indicated that the overall model fit for TPWB remained satisfactory across different university types. Scalar MI testing was conducted to examine the equivalence of intercepts across university types for the TPWB construct. The values of ΔTLI = −0.003, ΔCFI = 0.001, and ΔRMSEA = 0.000 suggested that the model had good fits across university types, indicating that the intercepts were equivalent. Finally, the residual MI (RMI) was examined across universities. The results showed that the RMI for TPWBS had values of ΔTLI = 0.015, ΔCFI = 0.014, and ΔRMSEA = −0.006. These findings indicate that the estimated factors of the TPWBS construct varied to some extent across different university types.

Experience in teaching. The analysis conducted on the years of teaching experience among university teachers yielded satisfactory results, as indicated by the acceptable fit to the data presented in Table 6. The model tested the measurement invariance (MI) across different levels of teaching experience, namely below 5 years, 6–10 years, and 11 years or more. The results of the MI analysis demonstrated that the model exhibited acceptable fit on all tested aspects, including the configural, metric, scalar, and residual tests. This suggests that the underlying structure of the measurement model remains consistent regardless of the years of teaching experience. Furthermore, the strict model, which examines the equivalence of item loadings, intercepts, and residual variances across the three levels of teaching experience, was successfully achieved. This indicates that the observed item responses and their associated parameters were found to be equivalent or equal across all levels of teaching experience.

4. Discussion and Implications

For a century, practitioners and researchers in various disciplines have primarily examined well-being by focusing on its pathological aspects [16,57] and assessed it using multiple scales [58]. However, recently, the scientific study of positive psychology and well-being has undergone a dramatic expansion because of its positive outcomes for individuals, organizations, and societies [59]. For this study, following [1], we conducted further psychometric validation of the five-factor TPWBS and tested the MI across gender, university classification, and experience in teaching to assess the positive psychological state and healthy professional functioning among university teachers in an Ethiopian setting. The study aimed to examine the psychometric properties of the TPWBS in the Ethiopian context, specifically among university teachers. The TPWBS is a five-factor model that measures different facets of teacher well-being, including authority, self-efficacy, job satisfaction, recognition, and aspiration. The study found that the TPWBS had good factor loadings, reliability, and construct validity, indicating that it is a valid measure of well-being for Ethiopian university instructors.

One notable finding of this study was the difference in the importance of different facets of well-being compared to a previous study by [1]. In the previous study, self-efficacy, job satisfaction, and recognition were found to be the most significant factors, while authority and aspiration were not supported [1]. However, in the current study, authority and aspiration were found to be important ingredients of teacher professional well-being in the Ethiopian context. This difference could be attributed to cultural variations and the demographic characteristics of the participants.

The convergent validity was supported by the correlations between teacher professional development facets and theoretically positively related (e.g., life satisfaction, emotional intelligence, and psychological capital) and negatively related (e.g., job burn out) constructs. We also explored another method to check convergent, divergent, and discriminant validity, and all proved that the TPWBS was valid. Overall, for the Ethiopian, Amharic-language version of the TPWBS sub scales, the AVE was greater than 0.05, and the AVE values were less than the MSV and squared inter-item correlations. Moreover, the convergent validity of the TPWBS was supported by positive correlations with constructs such as life satisfaction, emotional intelligence, and psychological capital, and negative correlations with job burnout. Furthermore, this study confirmed the divergent validity of the TPWBS by showing that the subscales had weak to moderate inter-item correlations and did not significantly correlate with each other. These findings strengthen the psychometric properties of the TPWBS and support its use as a valid measure of teacher well-being. We also found in this study that all five pillars of TPWBS showed weak to moderate inter-item correlations (see Appendix B).

The study also conducted measurement invariance tests to examine the TPWBS across different subgroups, including gender, university classification, and experience in teaching. The results showed that the five-factor model of the TPWBS was suitable for assessing well-being across these subgroups. This suggests that the TPWBS can be used to measure well-being consistently across different groups of university instructors in Ethiopia.

The implications of this study are twofold. First, the findings provide support for the use of the TPWBS in assessing the well-being of university instructors in Ethiopia. The validated scale can be used by researchers, educators, and policymakers to understand and promote well-being among teachers, which can have positive outcomes for individuals, organizations, and society as a whole.

Second, this study suggests that university managers and leaders can enhance teachers’ professional well-being by applying positive psychology principles [55,60]. Positive psychology interventions, based on theories such as Seligman’s positive psychology and Fredrickson’s broaden-and-build approach, can be implemented to promote well-being among university instructors [33,61,62]. These interventions may include fostering a supportive and empowering work environment, providing opportunities for professional development, recognizing and valuing teachers’ contributions, and promoting a positive organizational culture.

However, there are some limitations to consider. The study focused only on university instructors, so future research could examine the well-being of teachers in secondary and primary schools to provide a more comprehensive understanding. Additionally, this study highlighted the importance of considering cultural and demographic variables in understanding well-being, suggesting that future studies should explore the influence of variables such as culture, religion, ethnicity, and employment practices on teacher well-being using cross-cultural samples. The TPWBS also need further investigation in other cultures to check its suitability using different approaches based on the recommendation of [63,64].

TPWB is the most valuable construct associated with many psychological variables that determine teachers’ overall well-being, such as motivation, individual responsibility, and mindfulness [65,66,67]. Therefore, future studies will be checking its association.

In conclusion, this study contributes to the field of positive psychology and well-being research by validating the TPWBS in the Ethiopian context. The findings support the use of the TPWBS as a reliable and valid measure of teacher well-being and provide insights into the specific facets of well-being that are important for Ethiopian university instructors. This study also emphasizes the importance of positive psychology interventions in promoting well-being among teachers and suggests practical implications for university managers to enhance the well-being of their instructors.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/psycholint6030047/s1, File S1 the raw data of confirmatory factor analysis of the Teacher Professional Well-Being Scale reported in this study. Ref. [68] cited in Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization G.T.Z., E.N.E., Y.M. and D.G.B.; Methodology, G.T.Z., S.G., D.G.B. and D.F.M.; Formal analysis, G.T.Z.; Investigation, K.H.,E.N.E., D.F.M. and M.G.; Data curation, G.T.Z., D.F.M. and S.G.; Writing—original draft, G.T.Z., K.H., S.G. and D.G.B.; Writing—review & editing, E.N.E., M.G, D.F.M. and Y.M.; Supervision, G.T.Z. and Y.M.; Project administration, G.T.Z. and S.G.; Funding acquisition G.T.Z. and Y.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Scientific Foundations of Education Research Program of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and by the Digital Society Competence Centre of the Humanities and Social Sciences Cluster of the Centre of Excellence for Interdisciplinary Research, Development and Innovation of the University of Szeged. The authors are members of the New Tools and Techniques for Assessing Students Research Group.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Institute of Teacher Education & Behavioral Sciences, Wollo University, Ethiopia (protocol code 128/2021 and date of approval is 12 October 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The corresponding authors hold the data sets generated and analyzed during the study and are willing to share them upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Teacher Professional Well-Being Scale (TPWBS).

Table A1.

Teacher Professional Well-Being Scale (TPWBS).

| No. | Original English Version | Amharic Version | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I follow recent developments about my profession | ስለ ሙያዬ የቅርብ ጊዜ ለውጦችን እከተላለሁ:: | ||

| 2 | I have technical knowledge and skills, which are necessary for my profession. | ለሙያዬ አስፈላጊ የሆኑ ቴክኒካል እውቀቶች እና ክህሎቶች አሉኝ:: | ||

| 3 | If I want to do, I can carry out my profession requirements effectively even in most difficult condition. | ማድረግ ከፈለግኩ በጣም አስቸጋሪ በሆነ ሁኔታ ውስጥ እንኳን የሙያ ፍላጎቶቼን በብቃት ማከናወን እችላለሁ:: | ||

| 4 | I effectively and productively utilise technological devices in my professional area. | በሙያዬ አካባቢ የቴክኖሎጂ መሳሪያዎችን ውጤታማ እና ስኬታማ በሆነ መንገድ እጠቀማለሁ። | ||

| 5 | I have knowledge and skills to carry out my profession adequately | ሙያዬን በበቂ ሁኔታ ለመወጣት የሚያስችል እውቀትና ችሎታ አለኝ :: | ||

| 6 | I can perform my profession successfully in different places | በተለያዩ ቦታዎች ሙያዬን በተሳካ ሁኔታ ማከናወን እችላለሁ:: | ||

| 7 | I usually know how to get through to people (students, parents and school staff | ብዙውን ጊዜ ከሰዎች (ተማሪዎች፣ ወላጆች እና የትምህርት ቤት ሰራተኞች ጋር እንዴት እንደምገናኝ አውቃለሁ) | ||

| 8 | I have been performing my professional objectives in this school | በትምህርት ቤት ሙያዊ አላማዬን እያከናወንኩ ነው | ||

| 9 | In this school students’ demands of help are met immediately | በትምህርት ቤት ተማሪዎች እርዳታ ጥያቄዎች ካቀረቡ ወዲያውኑ ይሟላሉ። | ||

| 10 | Students in this class take care to create a pleasant learning atmosphere | በክፍል ውስጥ ያሉ ተማሪዎች አስደሳች የትምህርት ሁኔታ ለመፍጠር ጥንቃቄ አደርጋለሁ | ||

| 11 | When I enter the class all students are ready to students | ወደ ክፍል ስገባ ሁሉም ተማሪዎች ለመማር ዝግጁ ናቸው። | ||

| 12 | Students’ parents always support me. | የተማሪ ወላጆች ሁል ጊዜ ድጋፍ ይሠጡኛል ። | ||

| 13 | School staff is ready to help me if I demand about something related with teachers | የትምህርት ቤት ሰራተኞች ከማስተማር ጋር በተገናኘ አንድ ነገር ብጠይቅ ሊረዱኝ ዝግጁ ናቸው። | ||

| 14 | I receive appreciations because of my professional success. | በሙያዬ ስኬት ምክንያት ምስጋናዎችን አገኛለሁ። | ||

| 15 | School management always supports me in developing my capabilities of teaching | የትምህርት ቤት አስተዳደር የማስተማር ችሎታዬን በማዳበር ረገድ ሁሌም ይደግፈኛል። | ||

| 16 | I am sure that I would get support whenever I demand from school management | ከትምህርት ቤት አስተዳደር ድጋፍ በጠየቅኩ ጊዜ እገዛ እንደማገኝ እርግጠኛ ነኝ | ||

| 17 | When I issue a problem related with my profession, school management and I together solve the problem | ከሙያዬ ጋር የተያያዘ ችግር ሲመጣ ከትምህርት ቤት አስተዳደር ጋር በመሆን ችግሩን እንፈታዋለን | ||

| 18 | I always have an enthusiasm for doing professionally new things. | በሙያዊ አዳዲስ ነገሮችን ለመስራት ሁል ጊዜ ጉጉት ያድርብኛል። | ||

| 19 | I look for new ways to do my profession more effectively | ሙያዬን የበለጠ ውጤታማ ለማድረግ አዳዲስ መንገዶችን እቀይሣለሁ:: | ||

| 20 | I demand help of my colleagues to develop myself professionally | እራሴን በሙያ ለማዳበር የስራ ባልደረቦቼን እርዳታ እጠይቃለሁ። | ||

| 21 | My future plans on professional issues make me excited. | በሙያዊ ጉዳዮች ላይ የወደፊት እቅዶቼ በጣም ያስደሰቱኛል። | ||

| 22 | I know the rules demanded by teaching profession | መምህርነት ሙያ የሚጠየቁትን ህጎች አውቃለሁ:: | ||

| 23 | I and my colleagues make decision related with our profession in work environment. | እኔ እና ባልደረቦቼ በስራ አካባቢ ከሙያችን ጋር የተያያዙ ውሳኔዎችን እናደርጋለን:: | ||

| 24 | I consider others’ directions about professional issues but I make last decision. | ስለ ሙያዊ ጉዳዮች የሌሎችን መመሪያዎች ግምት ውስጥ አስገባለሁ ነገር ግን የመጨረሻውን ውሳኔ አደርጋለሁ:: | ||

| 25 | I have productive talks with the school administrators on professional issues. | ከትምህርት ቤቱ አስተዳዳሪዎች ጋር በሙያዊ ጉዳዮች ላይ ውጤታማ ንግግሮች አደርጋለሁ:: | ||

| 26 | I decide which materials and publications would be used in workplace. | የትኞቹ ቁሳቁሶች እና ህትመቶች በስራ ቦታ ጥቅም ላይ እንደሚውሉ እወስናለሁ:: | ||

| Scoring | ||||

| Original-English | Amharic Version | |||

| 1 | 7 | 1 | 7 | |

| To all items (1–7) | Very Strongly Disagree | Very Strongly Agree | እጅግ በጣም አልስማማም | እጅግ በጣም እስማማለሁ |

Note: Items 1–7 = Self-efficacy, Items 8–13 = Job satisfaction, Items 14–17 = Recognition, Items 18–21 = Aspiration, Items 22–26 = Authority.

Appendix B

Table A2.

The TPWBS Inter Item Pearson Correlation (N = 704).

Table A2.

The TPWBS Inter Item Pearson Correlation (N = 704).

| Items | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 0.523 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 0.588 ** | 0.566 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 0.611 ** | 0.506 ** | 0.586 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | 0.525 ** | 0.480 ** | 0.621 ** | 0.627 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | 0.550 ** | 0.475 ** | 0.589 ** | 0.578 ** | 0.566 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | 0.722 ** | 0.467 ** | 0.563 ** | 0.690 ** | 0.768 ** | 0.510 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | 0.221 ** | 0.239 ** | 0.257 ** | 0.234 ** | 0.262 ** | 0.267 ** | 0.244 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | 0.144 ** | 0.182 ** | 0.221 ** | 0.144 ** | 0.180 ** | 0.171 ** | 0.155 ** | 0.555 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 10 | 0.182 ** | 0.185 ** | 0.226 ** | 0.140 ** | 0.160 ** | 0.209 ** | 0.170 ** | 0.558 ** | 0.619 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 11 | 0.110 ** | 0.163 ** | 0.203 ** | 0.185 ** | 0.177 ** | 0.190 ** | 0.153 ** | 0.443 ** | 0.594 ** | 0.657 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| 12 | 0.133 ** | 0.144 ** | 0.177 ** | 0.149 ** | 0.173 ** | 0.163 ** | 0.150 ** | 0.349 ** | 0.395 ** | 0.419 ** | 0.393 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 13 | 0.164 ** | 0.189 ** | 0.205 ** | 0.142 ** | 0.195 ** | 0.220 ** | 0.171 ** | 0.515 ** | 0.564 ** | 0.618 ** | 0.529 ** | 0.329 ** | 1 | |||||||||||||

| 14 | 0.192 ** | 0.184 ** | 0.212 ** | 0.193 ** | 0.255 ** | 0.272 ** | 0.210 ** | 0.264 ** | 0.229 ** | 0.264 ** | 0.225 ** | 0.113 ** | 0.322 ** | 1 | ||||||||||||

| 15 | 0.118 ** | 0.154 ** | 0.173 ** | 0.147 ** | 0.205 ** | 0.167 ** | 0.161 ** | 0.191 ** | 0.181 ** | 0.163 ** | 0.140 ** | 0.116 ** | 0.178 ** | 0.709 ** | 1 | |||||||||||

| 16 | 0.161 ** | 0.207 ** | 0.185 ** | 0.183 ** | 0.224 ** | 0.237 ** | 0.184 ** | 0.247 ** | 0.234 ** | 0.205 ** | 0.171 ** | 0.106 ** | 0.218 ** | 0.703 ** | 0.574 ** | 1 | ||||||||||

| 17 | 0.144 ** | 0.178 ** | 0.197 ** | 0.152 ** | 0.252 ** | 0.207 ** | 0.197 ** | 0.276 ** | 0.254 ** | 0.277 ** | 0.247 ** | 0.155 ** | 0.282 ** | 0.715 ** | 0.571 ** | 0.628 ** | 1 | |||||||||

| 18 | 0.121 ** | −0.105 ** | 0.121 ** | −0.101 ** | 0.128 ** | 0.122 ** | 0.143 ** | −0.116 ** | 0.144 ** | −0.104 ** | 0.130 ** | 0.093 * | 0.127 ** | 0.090 * | 0.075 * | 0.088 * | 0.153 ** | 1 | ||||||||

| 19 | 0.175 ** | 0.117 ** | 0.124 ** | 0.140 ** | 0.155 ** | 0.081 * | 0.098 * | 0.006 * | −0.008 * | −0.097 * | −0.099 * | −0.083 * | −0.087 * | 0.091 * | 0.095 * | 0.083 * | 0.143 ** | 0.554 ** | 1 | |||||||

| 20 | 0.133 ** | 0.125 ** | 0.138 ** | 0.130 ** | 0.156 ** | 0.169 ** | 0.151 ** | −0.109 ** | −0.093 * | −0.089 * | −0.085 * | −0.083 * | −0.089 * | 0.091 * | 0.108 ** | 0.149 ** | 0.096 * | 0.500 ** | 0.774 ** | 1 | ||||||

| 21 | 0.146 ** | −0.109 ** | 0.133 ** | 0.092 * | 0.088 * | 0.099 * | 0.128 ** | 0.090 * | −0.097 * | −0.085 * | −0.083 * | −0.087 * | −0.088 ** | −0.093 * | −0.117 ** | 0.131 ** | 0.178 * | 0.526 ** | 0.710 ** | 0.739 ** | 1 | |||||

| 22 | 0.149 ** | 0.112 ** | 0.161 ** | 0.095 * | 0.075 * | 0.107 ** | 0.087 * | 0.082 * | 0.123 ** | −0.088 * | 0.195 ** | −0.158 ** | 0.123 ** | 0.140 ** | 0.135 ** | 0.163 ** | 0.115 ** | 0.424 ** | 0.628 ** | 0.671 ** | 0.696 ** | 1 | ||||

| 23 | 0.157 ** | 0.135 ** | 0.149 ** | 0.184 ** | 0.167 ** | 0.114 ** | 0.156 ** | −0.168 ** | −0.139 ** | −0.185 ** | −0.109 ** | −0.183 ** | −0.159 ** | −0.243 ** | −0.124 ** | −0.216 ** | 0.116 ** | 0.450 ** | 0.661 ** | 0.693 ** | 0.655 ** | 0.681 ** | 1 | |||

| 24 | 0.136 ** | 0.132 ** | 0.147 ** | 0.123 ** | 0.185 ** | 0.085 * | 0.090 * | −0.082 * | −0.092 * | −0.099 * | −0.090 * | −0.118 ** | −0.095 * | −0.078 * | −0.083 * | −0.086 * | −0.112 ** | 0.410 ** | 0.596 ** | 0.569 ** | 0.619 ** | 0.653 ** | 0.717 ** | 1 | ||

| 25 | 0.090 * | −0.103 ** | 0.016 * | −0.005 * | 0.090 * | 0.087 * | 0.107 ** | −0.094 * | −0.085 * | −0.098 ** | −0.099 | −0.094 * | −0.081 * | −0.087 * | −0.070 * | 0.097 * | 0.102 ** | 0.401 ** | 0.566 ** | 0.586 ** | 0.584 ** | 0.592 ** | 0.737 ** | 0.676 ** | 1 | |

| 26 | 0.086 * | 0.094 * | 0.115 ** | 0.130 ** | 0.083 * | 0.090 ** | 0.068 ** | −0.095 ** | −0.065 ** | −0.112 ** | −0.042 ** | −0.050 ** | −0.095 * | −0.140 ** | −0.170 ** | −0.105 ** | 0.110 ** | 0.394 ** | 0.570 ** | 0.586 ** | 0.567 ** | 0.607 ** | 0.700 ** | 0.666 ** | 0.757 ** | 1 |

Note: *&**. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 and 0.01 level (2-tailed) respectively. Note: Items number 1–7 = Self-Efficacy, 8–13 = Job Satisfaction, 14–17 = Recognition, 18–22 = Authority, 23–26 = Aspiration.

References

- Yildirim, K. Testing the main determinants of teachers’ professional well-being by using a mixed method. Teach. Dev. 2015, 19, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, K.; Arastaman, G.; Daşci, E. Developing, Testing and Implementing the Scale of Teachers’ Professional Well-Being. J. Theor. Educ. Sci. 2014, 8, 486–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, F.; Price, D. Well teachers, well students. J. Stud. Wellbeing 2010, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retallick, J.; Butt, R. Professional well-being and learning: A study of teacher-peer workplace relationships. J. Educ. Enq. 2004, 5, 85–99. [Google Scholar]

- Viac, C.; Fraser, P. Teachers’ well-being: A framework for data collection and analysis. In OECD Education Working Papers; No. 213; OECD: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorov, A.; Ilaltdinova, E.; Frolova, S. Teachers’ professional well-being: State and factors. Univers. J. Educ. Res. 2020, 8, 1698–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, R.; Retallick, J. Professional well-being and learning: A study of administrator- teacher workplace relationships. J. Educ. Enq. 2002, 3, 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Well-Being Indicators; OECD: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Horn, J.E.; Taris, T.W.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Schreurs, P.J.G. The structure of occupational well-being: A study among Dutch teachers. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2004, 77, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S.; Torrente, C.; McCoy, M.; Rasheed, D.; Lawrence Aber, J. Cumulative risk and teacher well-being in the democratic republic of the Congo. Comp. Educ. Rev. 2015, 59, 717–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brdar, I. The Human Pursuit of Well-Being: A Cultural Approach; Springer Science+Business Media B.V.: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Helliwell, J.F.; Kahneman, D. International Differences in Well-Being; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kern, M.L.; Waters, L.; Adler, A.; White, M. Assessing Employee Wellbeing in Schools Using a Multifaceted Approach: Associations with Physical Health, Life Satisfaction, and Professional Thriving. Psychology 2014, 5, 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Wang, L. Validation of emotional intelligence scale in Chinese university students. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2007, 43, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zewude, G.T.; Hercz, M. The Teacher Well-Being Scale (TWBS): Construct validity, model comparisons and measurement invariance in an Ethiopian setting. J. Psychol. Afr. 2022, 32, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotze, M. The influence of employees ’ cross-cultural psychological capital on workplace psychological well-being. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2017, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zewude, G.T.; Hercz, M.; Duong, N.T.N.; Pozsonyi, F. Teaching and Student Evaluation Tasks: Cross-Cultural Adaptation, Psychometric Properties and Measurement Invariance of Work Tasks Motivation Scale for Teachers. Eur. J. Educ. Res. 2022, 11, 1245–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soini, T.; Pyhältö, K.; Pietarinen, J. Pedagogical well-being: Reflecting learning and well-being in teachers’ work. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract. 2010, 16, 735–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aelterman, A.; Engels, N.; Van Petegem, K.; Verhaeghe, J.P. The well-being of teachers in Flanders: The importance of a supportive school culture. Educ. Stud. 2007, 33, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Fernandez, J.; Gomez-Gascon, T.; Beamud-Lagos, M.; Cortes-Rubio, J.A. Professional Quality of Life and Organiza- tional Changes: A Five Year Observational Study in Health Care. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2007, 7, 101. Available online: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/7/101 (accessed on 3 October 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowlinson, S.; Slavenburg, S.; Poon, S.W.; Jia, Y. Organizational Environment and Professional Well-being: Mapping Worklife Landscape in the Construction Industry. In Proceedings of the Universitas 21 International Graduate Research Conference: Sustainable Cities for the Future, Melbourne and Brisbane, Germany, 29 November–5 December 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zewude, G.T.; Hercz, M. Psychometric Properties and Measurement Invariance of the PERMA Profiler in an Ethiopian Higher Education Setting. Pedagogika 2022, 146, 209–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouskeli, V.; Loumakou, M. Resilience and occupational well-being of secondary education teachers in Greece. Issues Educ. Res. 2018, 28, 43–60. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, S. Effects of customer experience across service types, customer types and time. J. Serv. Mark. 2018, 32, 400–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konu, A.; Viitanen, E.; Lintonen, T. Teachers ’ wellbeing and perceptions of leadership practices. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2021, 3, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehdinezhad, V. Relationship between High School teachers ’ wellbeing and teachers ’ efficacy. Acta Scientiarum. 2012, 34, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.; Ruch, W.; Junnarkar, M. Effect of the Demographic Variables and Psychometric Properties of the Personal Well-Being Index for School Children in India. Child Indic. Res. 2015, 8, 571–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strang, K.D. The Palgrave Handbook of Research Design in Business and Management; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.S.; Law, K.S. The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude: An exploratory study. Leadersh. Q. 2002, 13, 243–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J.D. Emotional intelligence. Imagin. Cogn. Personal. 1990, 9, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthans, F.; Avolio, B.J.; Norman, S.M. Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Pers. Psychol. 2007, 60, 541–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zewude, G.T.; Bereded, D.G.; Abera, E.; Tegegne, G.; Goraw, S.; Segon, T. The Impact of Internet Addiction on Mental Health: Exploring the Mediating Effects of Positive Psychological Capital in University Students. Adolescents 2024, 4, 200–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirzyte, A.; Perminas, A.; Biliuniene, E. Psychometric properties of satisfaction with life scale (Swls) and psychological capital questionnaire (pcq-24) in the lithuanian population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görgens-Ekermans, G.; Herbert, M. Psychological capital: Internal and external validity of the Psychological Capital Questionnaire (PCQ-24) on a South African sample. SA J. Ind. Psychol. 2013, 39, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choisay, F.; Fouquereau, E.; Coillot, H.; Chevalier, S. Validation of the French Psychological Capital Questionnaire (F-PCQ-24) and its measurement invariance using bifactor exploratory structural equation modeling framework. Mil. Psychol. 2021, 33, 50–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cid, D.T.; do Carmo Fernandes Martins, M.; Dias, M.; Fidelis, A.C.F. Psychological capital questionnaire (PCQ-24): Preliminary evidence of psychometric validity of the Brazilian version. Psico-USF 2020, 25, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerbing, D.W.; Anderson, J.C. An Updated Paradigm for Scale Development Incorporating Unidimensionality and Its Assessment. J. Mark. Res. 1988, 25, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. Maslach Burn-Out Inventory Manual, 3rd ed.; Consulting Psychologists Press: Mountain View, CA, USA, 1996; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277816643 (accessed on 27 June 2023).

- Zewude, G.T.; Mária, H.; Taye, B.; Demissew, S. COVID-19 Stress and Teachers Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Sense of Coherence and Resilience. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2023, 13, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the Process of Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Self-Report Measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. IBM SPSS Statistics 26 Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 16th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Black, W.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Annabel Ainscow: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation coefficients: Appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, H.F. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 1974, 39, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, P. Structural equation modelling: Adjudging model fit. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2007, 42, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, J.H. Understanding the limitations of global fit assessment in structural equation modeling. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2007, 42, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2008, 6, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millsap, R.E. Stastical Approaches to Measurement Invariance; Routledge: NewYork, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Putnick, D.L.; Bornstein, M.H. Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: The state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Dev. Rev. 2016, 41, 71–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.F. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2007, 14, 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research, 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, G.W.; Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2009, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spilt, J.L.; Koomen, H.M.Y.; Thijs, J.T. Teacher Wellbeing: The Importance of Teacher—Student Relationships. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 23, 457–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, M.W.; Lopez, S.J. Positive Psychological Assessment: A Handbook of Models and Measures, 2nd ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M.E.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Positive psychology. An introduction. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Building well-being among university teachers: The roles of psychological capital and meaning in life. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2018, 27, 594–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The broaden−and− build theory of positive emotions. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 2004, 359, 1367–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sass, D.A.; Schmitt, T.A.; Marsh, H.W.; Sass, D.A.; Schmitt, T.A.; Marsh, H.W. Evaluating model fit with ordered categorical data within a measurement invariance framework: A comparison of estimators. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2014, 21, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkin, T.R. A Review of Scale Development Practices in the Study of Organizations. J. Manag. 1995, 21, 967–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazos, T.A. Applied Psychometrics: Sample Size and Sample Power Considerations in Factor Analysis (EFA, CFA) and SEM in General. Psychology 2018, 9, 2207–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriazos, T.A.; Stalikas, A. Applied Psychometrics: The Steps of Scale Development and Standardization Process. Psychology 2018, 9, 2531–2560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkáčová, H.; Maturkanič, P.; Pavlíková, M.; Nováková, K.S. Online Media Audience During the Covid-19 Pandemic As an Active Amplifier of Disinformation: Motivations of University Students To Share Information on Facebook. Commun. Today 2023, 14, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zewude, G.T.; Oo, T.Z.; Gabriella, J.; Józsa, K. The Relationship among Internet Addiction, Moral Potency, Mindfulness, and Psychological Capital. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2024, 14, 1735–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ringle, C.M.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. “SmartPLS 4”. Bönningstedt: SmartPLS. 2024. Available online: https://www.smartpls.com (accessed on 2 July 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).