1. Introduction

The entertainment phenomenon of the

Game of Thrones (GoT) franchise has captured countless millions of viewers across the world, both through paid subscriptions and illegal downloading.

1 In the USA alone, 30 million people watched each episode of the show’s seventh season in 2017 (

Koblin 2017) and the broadcast rights see it appear in another 170 states and territories globally. Bootleg file sharing accounted for another one billion downloads of that 2017 season (

Andrews 2017). Add to this the countless words and web pages that talk about GoT, the marketing of the original books, spin-off games, location tourism and a myriad of other phenomena, all of this combined makes GoT arguably the most successful fantasy franchise ever in terms of fiscal and cultural impact. Of greatest significance is that the television version has acted as a ‘gateway’ to the fantasy genre, crossing over to become a mainstream product that attracted a new and diverse audience that would not previously have been consumers of such works (

Williams 2012).

These newcomers and established fantasy fans alike are presented with a backdrop world that conforms to many of the standard tropes of the genre that is largely spawned from the works of J.R.R. Tolkien: a pseudo-medieval culture placed upon a European-like continent (Westeros) with the addition of supernatural elements (

Young 2014). Whilst the authenticity of this medieval world is open to debate (for example, see

Carroll 2018), there is a definite effort on the part of the author to make the setting credible, if not necessarily an attractive place to live: what G.R.R. Martin himself has referred to as “gritty realism” and a repudiation of the “Disneyland middle ages” (

Martin 2011).

With an inspiration in the dynastic struggles of the Wars of the Roses, one theme that Martin has chosen to emphasise in GoT is family identity. In a realm that is formed from uniting seven historic kingdoms, the complex interactions between the senior nobility and their vassals places a great weight on shifting patterns of allegiances. Bonds and betrayal are everything in a political landscape where ‘Who’s who?’ is a matter of life and death.

Linking this emphasis on family with the setting of medieval realism, Martin has made great use of the historic art of heraldry in a very modern approach to ‘branding’ his characters. The effort that has gone into creating the coats of arms of his imaginary world is significant, with over 400 different designs appearing in the books and related material (

Garcia and Antonsson n.d.).

2 Such prolific blazonry

3 places GoT far beyond any other fantasy franchise in its heraldic detail.

4 In a crossover between fantasy medievalism and real-world commercialism, some of these coats of arms have become attached to the marketing of the series and its associated merchandise. Devoted fans have even gone as far as to use these designs as tattoos.

5Given the impact of the saga in popular culture and its central use of coats of arms, an examination of the heraldic system of GoT is warranted. The purpose of this paper is not to attempt a complete historical comparison between fictional heraldry and various historical systems. Rather, by observing the role of heraldry in this imaginary world and describing some of its idiosyncrasies, it will be shown that whilst Martin sets his foundation firmly in the traditional, he then extends this into the fanciful; in much the same manner as he does with other faux-historical aspects of his work.

2. Family Business

The right to a coat of arms is dictated by one’s social position in the fantasy world of GoT, with nobles and knights being the primary bearers of these. However, the feudal rank system of Westeros is rather less complex than that of European history. There is a monarch of the united ‘Seven Kingdoms’ and then there are numerous hereditary ‘lords’.

6 The latter are not differentiated into any denominated sub-classes such as dukes, earls, barons etc., however their individual status is rather derived from family wealth, history, political connections and so forth. For example, there are several ‘Great Houses’ (such as the Starks and Lannisters) that have significantly higher status and wealth than the average noble family. These hold the fealty of many smaller houses who may in turn have their own ‘bannermen’ or ‘landed knights’ who administer but a few smallholdings. The lesser families range from those with substantial status of their own down to others that are on the edge of penury and whose glories may have long receded. Regardless of their place in the pecking order, all of these noble houses are armigerous.

Key to the study of the heraldic practice in GoT is that the arms of the nobility are fully familial rather than primogenitive. All legitimate descendants and relatives bear the same undifferenced arms of their noble family. Moreover, retainers and common soldiers who are in service to a house will also display these arms upon their clothing and shields as a kind of uniform. In the television version, this leads to displays of visual consistency on the battlefield that were unknown in medieval times.

In GoT, the arms of noble houses therefore function more like a transmissible version of a corporate logo. Just like modern logos, the GoT armorial bearings and even their colours are used in all manner of ways, such as flags, badges, decorations, clothing and product trademarks. Whilst there may be some similarity to the medieval practice of placing devices and ‘cognizances’ in carvings, tapestries, artworks and buildings to indicate patronage and social connection, the striking scale with which this is depicted in GoT transcends this historical basis. Just as a corporate uniform or t-shirt serves to identify an employee in the modern world, the allegiance of an individual in GoT can be recognized instantly by the arms he bears, no matter whether or not he is the blood relative of the ‘owner’ of that blazon. Whilst there is nothing akin to the office of a herald in GoT, the memorisation and quick identification of coats of arms is considered a desirable political skill and noble children are schooled in this and praised for their heraldic recall (

Martin 2000b, p. 519).

Given this desire for consistent familial branding, the act of differencing arms is limited in GoT. A formal system of cadency does not exist, and all male siblings of the ruling lord and their male relatives bear the undifferentiated arms of their house. In general practice there is, therefore, no visual heraldic difference between a first and a third cousin, leading to far fewer blazons in circulation than was the case in European history.

7 There are exceptions described in the books, however these are usually voluntary. For example, the arms of House Tyrell (a golden rose on a green field) are adapted by Loras Tyrell to show three gold roses (see

Figure 1), signifying him as the third son of Lord Tyrrell (

Martin 1999, p. 251). This difference is related to his career as a tourney knight, allowing him to be more specifically identified in the lists.

A secondary heraldic class in the imaginary world of GoT is made up of the knights. Knighthood is non-hereditary and can be bestowed by any existing knight upon any male (even a commoner) after they have fulfilled satisfactory time in service as a page or squire and/or demonstrated martial prowess or some extraordinary devotion.

8 As with nobles, knights range in their status from the ‘landed knights’, who may control castles and villages for a liege lord, down to the penniless mercenary ‘hedge knights’ or those who have resorted to brigandry to get by (a marked contrast with the romantic Victorian-era notion of the chivalric knight (

Carroll 2018)). Upon achieving knighthood, the recipient is referred to as ‘Ser’, and if they have no previous coat of arms (through noble birth), they can choose their own new design. However, these coats of arms will not pass to their offspring. Given their multiplicity and short-lived nature, these offerings do not carry that high of a level of brand recognition that the designs of the noble houses attain. The coats of arms borne by these knights can be whimsical or mocking, such as the crazed white mouse with red eyes borne by the diminutive but ferocious Ser Shadrich (

Martin 2005a, p. 94).

To close the heraldic loop, knights and others rendering significant acts of service to the monarchy or high aristocracy may themselves be ennobled. This sees them as founders of a noble house and permits them to create or change their own arms, with these subsequently becoming hereditary brands. The opposite can also occur, with traitors or others who fall out of favour having their noble rank stripped or downgraded, thus leading to their arms being stricken, modified or forfeited to other branches of their family tree.

Therefore, despite the relative simplicity of the feudalism that informs the world of GoT, the heraldic customs in this fantasy realm have their own complexity. More than this, coats of arms form an arguably even more important identity function than they do in our world, inhabiting a space somewhere between the national flag and the corporate brand. Far from being merely ceremonial or proof of pedigree, these blazons and the power behind them are the bedrock of political power.

3. Variations of the Fields

Within this feudal and knightly framework, Martin has created a solid heraldic basis for his stories with a firm grounding in traditional blazonry. At the same time, he has incorporated a number of his own ideas that extend the GoT heraldic system and provide intriguing points of difference for those who are accustomed to real-world traditions.

The most obvious of these differences is in tincture. The world of GoT has no standardized heraldic nomenclature and Martin tends to use plain language colour references when describing blazons rather than the formal, mainly French-based terminology that developed in Europe as a sociolect for those who were professionally involved in heraldic studies and illustration. For example, Martin describes the blazon of House Cockshaw as “three feathers, red, white and gold on black” instead of “sable, a plume gules, argent and or”. Occasionally the blazons combine the two approaches, using modern English words for the tinctures and then heraldic vocabulary for the divisions, ordinaries, sub-ordinaries etc. For example, “Per fess: five black roundels on grey over green and white lozengy”. (For the purposes of this paper, Martin’s approach of plain English will be used rather than ‘translating’ his blazons into conventional heraldic descriptions.)

In terms of colour, we are, therefore, presented with simple terms such as red, green, blue and so forth without any mention of shade. However, more detailed adjectives are provided for other designs, such as burgundy, violet, bone or grey-green. In one way, this opens a very opulent palette for the audience, however it is at odds with the more rigid system that those who are interested in heraldry may be accustomed to. Nevertheless, Martin’s extrapolations may even be more appropriate than expected given the roots of the art: “While the colours of heraldry are usually rich, they may vary as to shade within reasonable limits. No exact meaning attaches to the worlds gules, azure etc.” (

Boutell and Brooke-Little 1973, p. 28).

Some of Martin’s inventiveness with tincture does cause ambiguity in imagining the arrangements. In formal blazonry, ‘argent’ is used to denote white for purposes of illustration, however as a ‘metal’, it is also conceivably silver and grey. Martin makes no such assumptions and employs all sorts of vocabulary to distinguish shades at this pale end of the palette, even mixing them in the same blazon (House Stark: a grey direwolf on white. House Bywater: fretty blue on white, three silver fish on a blue chief.) Yellow and gold are also used in this manner. Martin thus frequently breaks the well-known ‘rule of tincture’ where a metal may not be placed on a metal, nor colour on colour. However, this does permit the imagination to picture the difference between a metallic (silver) and a solid (white) colour in the blazon. Adding to this complexity are other metallic tinctures such as iron and bronze. However, how might the colour of iron be differentiated from grey, or bronze from brown?

There are also a multitude of blazons in this imaginary world that invoke very subjective shades, even if we imagine their description to follow the heraldic concept of ‘proper’ (depicted in their natural colour). For example, the arms chosen by Ser Duncan the Tall in the prequel stories to GoT are an elm tree on a field of sunset with a shooting star above (

Martin 2017, p. 50). Whilst the elm tree is detailed as green and brown (or proper), the field of ‘sunset’ is more of a mystery. Is it a single solid colour or a gradation? Does it imply a sunset of Orange? Red? Pink? Purple? And what colour is the shooting star? (see

Figure 2a). Other examples of such interpretive field tinctures are ‘oak’, ‘masonry’, ‘bone’ and ‘sand’.

Divisions and charges in GoT are for the most part similar to real world heraldry, though there are some items that are specifically related to the culture and geography of the imaginary land. For example, the main religion of Westeros is ‘The Faith of the Seven’, a septpartite pantheon of deities that together embody facets of a whole. A seven-pointed star is used as a symbol of this religion in much the same way that the shamrock has been used to symbolise the Christian trinity (see

Figure 2b). For this reason, stars of seven points are common heraldic charges in the stories, a device that is exceedingly rare in our own world compared to the standard mullet of five points.

9Fantasy flora and fauna form another source of different adornment for the arms of the stories. Beasts such as dragons and unicorns appear as they do in our own heraldry, however there are also depictions of animals and plants that are native to the imagined world. These include the ‘lizard lion’ (apparently something like a crocodile), the manticore (not like our own heraldic version, however rather a beetle-scorpion hybrid) and the ‘weirwood tree’ (a type of ancient tree with supernatural attributes).

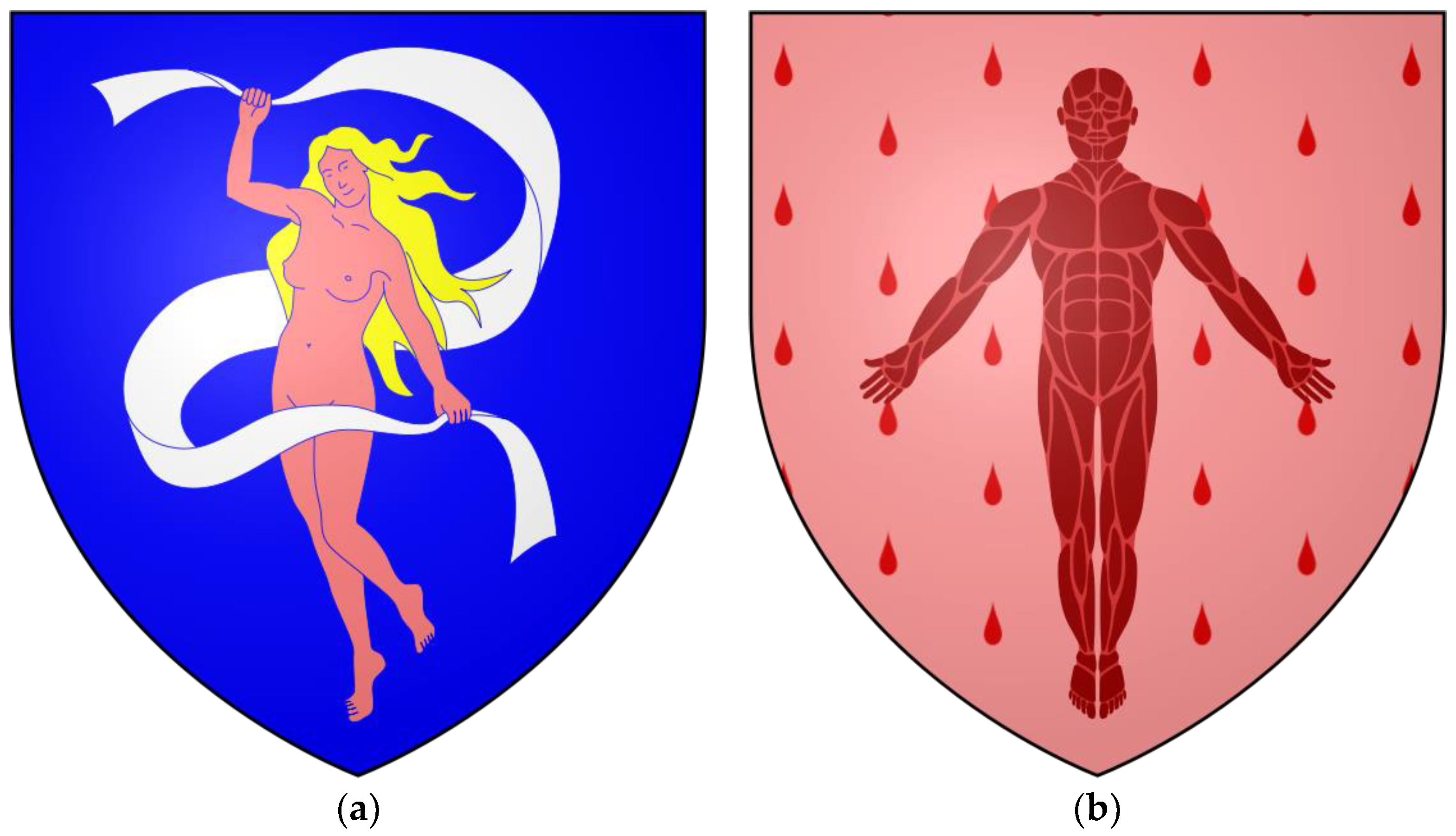

Of considerable difference with our own heraldic conventions is that Martin offers blazons that employ charges of significant detail (see

Figure 3). Many of these are so complicated that they would be more akin to the supporters of formal heraldic designs. For example:

House Sunderly: a drowned man, pink and pale, floating upright in a blue-green sea, his hair streaming upwards, as fish nibble at his limbs (

Garcia and Antonsson n.d.).

House Umber: a roaring giant, brown-haired and wearing a skin, with broken silver chains, on flame-red (

Martin 1996, p. 569).

If we consider the practicalities of these designs, they are curious choices; especially given that in this fantasy world the coats of arms tend to be worn as a brand on all household retainers, men-at-arms and equipment. How would it be possible to render such complex illustrations consistently across all manner of shields, flags, tunics and so forth? And what would be the cost involved in producing so many renditions in such detail? Likewise, if we consider that the basic purpose of a coat of arms is to distinguish an individual on the battlefield or at distance, then it is hard to see how these minutely detailed and often low-contrast designs would be practical for such purposes. The artistic designers of the TV series perhaps had similar feelings on this last question. In rendering the coats of arms for some houses, they have opted to create new arrangements that offer greater visual distinction. The best example of this appears in the shields of the Boltons, where the original flayed man on pink with drops of blood that is described in the books has been altered to give a higher contrast design showing an inverted red man spread across a white saltire on a black field.

A final curiosity of this fantasy world’s heraldry are two examples where the coats of arms consist only of a single colour. Neither of these are familial arms, however instead they belong to celibate martial orders with specific missions. The first of these is the Kingsguard, the seven-member personal bodyguard of the monarch of the Seven Kingdoms, who all carry a plain white shield. The second example is the Night’s Watch, a formation of outcasts and pressed criminals who carry solid black shields in their duty of protecting the northern wall of the Kingdoms from foes who are both human and supernatural.

10 4. Simple Arms for Powerful People

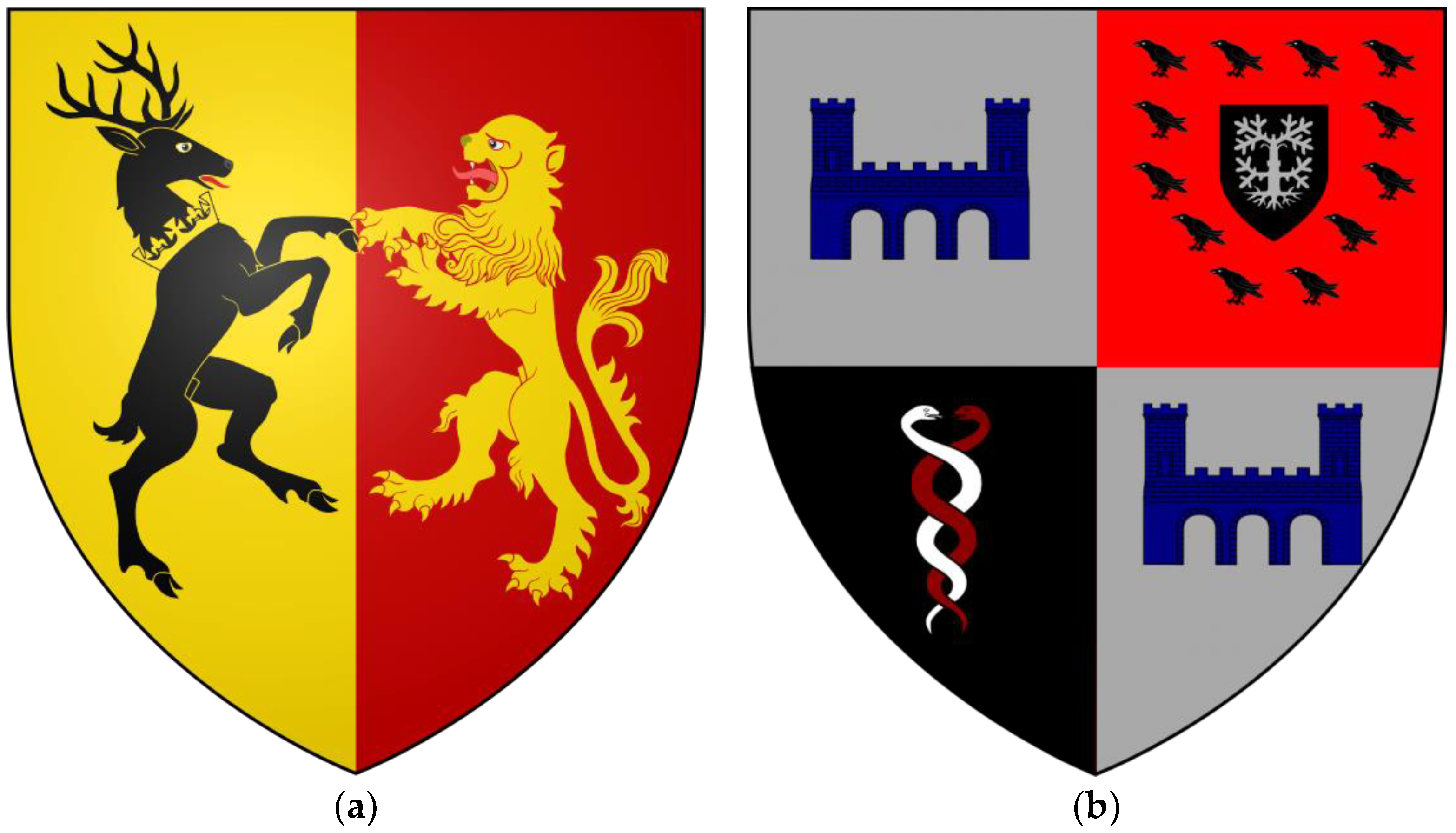

Within the heraldic world of Westeros, there appears to be a reverse hierarchy of simplicity, with the most important noble families (“The Great Houses”) possessing blazons that are bold and uncluttered by divisions or multiple charges. With only two exceptions, the arms of these leading families all consist of an undivided field with a single charge. (See

Figure 4). Even the exceptions (Tully and Arryn) are still straightforward and distinctive:

House Targaryen a red dragon of three heads on a black field;

House Stark a grey dire wolf running on a white field (in the TV series, it is depicted only as a wolf’s head erased);

House Lannister a gold lion on a red field (generally depicted as a lion rampant

11);

House Baratheon a crowned black stag on a gold field;

House Tyrell a golden rose on a green field (generally depicted as a rose in the Tudor fashion);

House Martell a gold spear piercing a red sun on an orange field;

House Greyjoy a golden kraken on a black field;

House Arryn a blue falcon on a white moon on a blue field (generally depicted as blue, upon a white plate a falcon soaring of the field).

House Tully a silver trout on a field of red and blue (field generally depicted either as wavy or paly wavy azure and gules).

These minimal and classic heraldic arrangements make good sense in the context of the ‘branding’ function that coats of arms fulfil in Martin’s world. The important families are readily identifiable through coats of arms that are not only bold, however are also easily distinguishable from one another. This visual identity has even transcended the fantasy world, with the arms of the central families being heavily used on merchandise and marketing material that is associated with the books and TV series.

12 This simplicity and ‘brand identity’ is maintained throughout the generations because the use of marshalling to denote marriage alliances is extremely uncommon in the world of GoT. Marriage, even between the most powerful dynasties, generally sees the wife surrender the right to her birth arms and adopt that of her husband’s line. Whilst any alliance and its political implications will be known to all, there seems to be no compulsion to display this in an armorial bearing. In many ways, this minimalism offers the opposite case to the convoluted heraldic quarterings and mergings of the high European aristocracy, where visual representations of dynastic bonds and provincial unions were considered desirable proof of bloodline and allegiance.

Exceptions to this avoidance of matrimonial marshalling are few, however the most noteworthy example is that of King Joffrey Baratheon, who takes the impaled arms of his father and mother, thus signifying the union of two great houses however, more importantly, the establishment of a new royal line (see

Figure 5a). At the other end of the prestige spectrum, marshalling is occasionally practised by minor male heirs as a means of trying to bolster their status. This might see them personally adapt their inherited family blazon to include the arms of a wife coming from a more prestigious house. Examples of this occur in the fecund and disreputable Frey family, where the head of the house has sired over 100 blood descendants through seven marriages. In order to differentiate themselves from their multiple siblings and half-siblings or to try and garner greater esteem, some of the males quarter their paternal arms with those of their better bred spouses (see

Figure 5b). This is seen as a gauche pretense by more prominent nobles (

Martin 1999, p. 181).

Below this pinnacle of the feudal tree are the various houses of middle and lower prestige and, finally, the knights, from landed to penniless. The blazons in these cases tend to get more complicated (and in some cases ludicrous) the further down the social pecking order the bearer exists. The designs present more divisions, more charges, fanciful tinctures and odd illustrations. Although some might still follow the formula of a single charge upon a solid field, one of these elements might be unusual by traditional standards (see

Figure 6). For example, the field is pink or the charge is a peacock proper or a white badger. Given the fantasy world’s emphasis on family reputation, it is also hard to see how some of the charges convey this. How can, for example, a toad (House Vypern) or a vulture snatching a baby (House Blackmont) express anything virtuous?

Unlike the Great Houses, some lesser families apparently use their coats of arms to assert some aspect of their ‘story’ as a means of identification. This may occur in several ways, such as:

Canting (House Ironsmith: a black sword upright between four black horseshoes on gold, a grey-green border).

References to a liege family (for example, fish used in the arms of some families loyal to House Tully).

A family quality or reputation (for example, the flayed man of the Boltons).

References to some story of note or personal achievement in the history of the house. This may perhaps relate to the deed that caused an ancestor to be ennobled.

In the last case, these personal anecdotes may result in quite elaborate and absurdly complicated blazons. For example, House Wydman was founded by a knight who was ennobled following the defeat of five opponents during a jousting tournament. Each of the victories occurred against members of significant families. The blazon of this relatively inconsequential house thus seeks to impart grandiosity by using broken lances and the charges of the defeated houses: “5 splintered lances, 3–2, striped blue and white with blue pennons, on yellow, beneath a white chief bearing a red castle, a green viper, a black broken wheel, a purple unicorn and a golden lion” (

Garcia and Antonsson n.d.).

5. Heralds Do Not Pun, They Cannot

In respect to canting arms, frequent use of this heraldic punning is made in the blazonry of GoT (see

Figure 7). In some cases, the descriptions are allusive to the name of the family. For example:

House Webber uses a spider in a cobweb.

House Meadows depicts flowers on a green field.

House Waxley has six burning candles.

In other examples, the arms are a reference to the ancestral seat of the family. The rulers of the principality of Dorne, the Martells, have their stronghold in Sunspear. Their blazon is a literal representation of this, with a gold spear transfixing a red sun. Among numerous other examples, House Smallwood of Acorn Hall depicts acorns and House Ryger of Willow Wood uses the appropriate tree as their device.

Canting is also used to convey inside jokes to the core fantasy audience of the series. Martin has included a few houses that are allusions to other fantasy authors and their works, including his own. There are, for example, two houses with the name of Vance (Vance of Wayfarer’s Rest and Vance of Atranta). This is a reference to Jack Vance, a seminal fantasy author who Martin has acknowledged as a favourite. The Wayfarer’s Rest branch of the family is blazoned quarterly a black dragon on white, two golden eyes in a golden ring on black. The dragons are an allusion to Vance’s 1963 novella

The Dragon Masters. The eyes (and the name of the house’s ancestral seat) refer to his story

Liane the Wayfarer, where a rogue with a magical ring that allows him to escape to a pocket world of complete darkness has his golden eyes stolen by a monster (

Garcia and Antonsson 2012). House Jordayne is a reference to prolific writer Robert Jordan and incorporates a golden quill in its coat of arms (ibid.). Among several others, there is also a heraldic homage to another influential fantasy writer, Roger Zelazny. The obviously named House Rogers uses nine unicorns around a maze as its coat of arms, representing various features of Zelazny’s work: a 1983 anthology called

Unicorn Variations and the nine princes of his

Chronicles of Amber series, which centres on a mystical labyrinth (ibid.).

6. Gory Details and Regional Variations

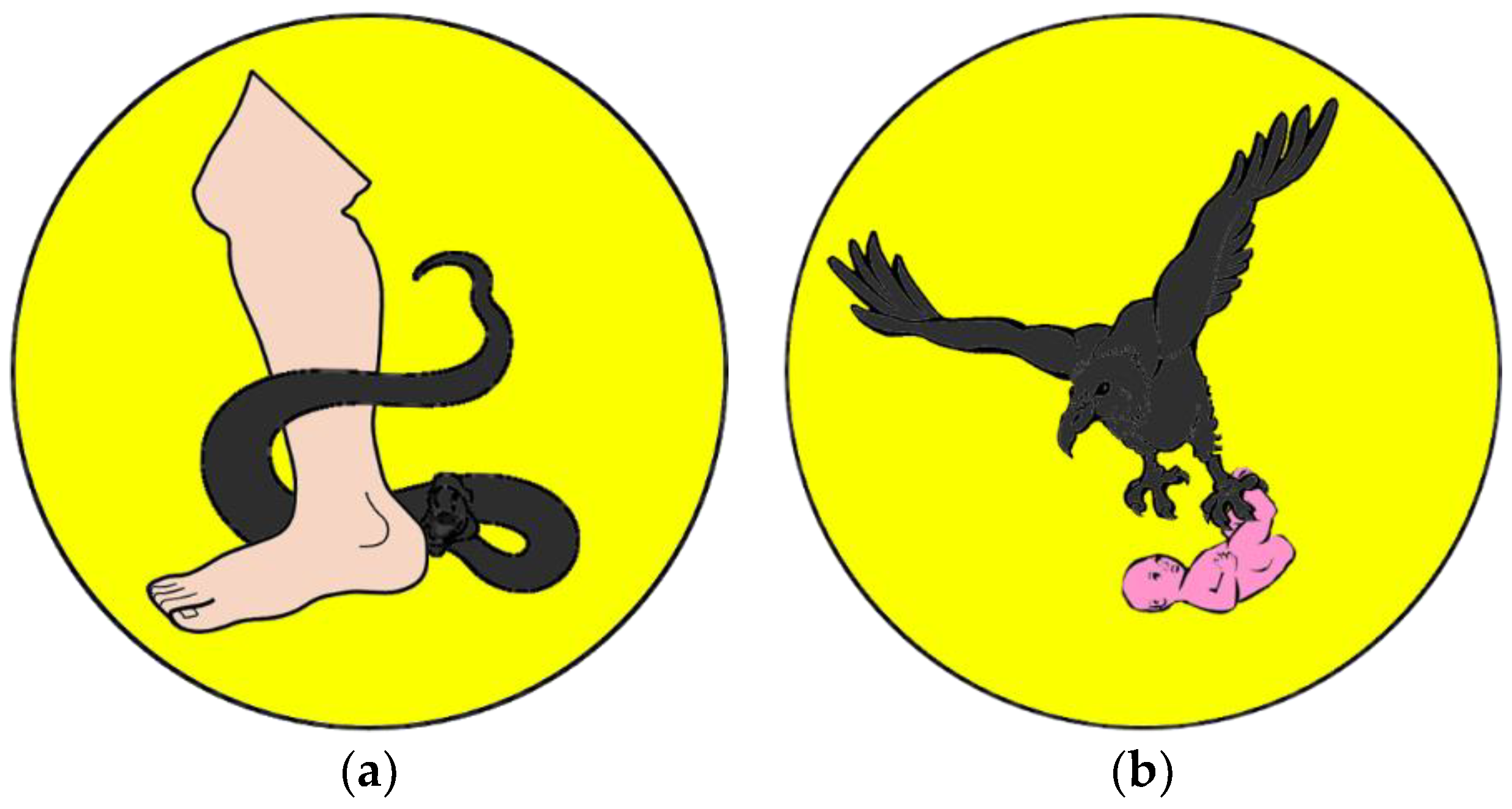

As with European heraldry, the continent of Westeros shows some regional variations in its conventions. Among the united Seven Kingdoms that make up the lands of Westeros, some of the constituent domains display local idiosyncrasies in their coats of arms that contrast with the more standard trends throughout the rest of the realm.

The first example of this is within the Principality of Dorne. This region lies in the far south of the continent and the geography and culture of this province are based upon the medieval Caliphate of Cordoba (

Martin 2000a). The Dornish are therefore the Moors of Martin’s world, complete with opulent palaces that are equipped with marbled fountains, swimming pools, citrus groves and arabesque fluted columns. The inhabitants of Dorne also demonstrate many of the Orientalist clichés of Western literature, being underhanded, cruel, emotionally fiery, prone to using poison and sexually profligate (

Hardy 2018).

As with its culture, the coats of arms of Dorne are somewhat different from those of their northern neighbours. The first of these is in the shape of the field. In the other six components of the kingdom, the conventional heater type shield is used to display the blazons. However, in the armorial artwork for the heraldry of Dorne, these coats of arms are presented on circular fields (see

Figure 8). This is not explicitly described in the original novels, however the practice has arisen out of supplementary material produced in co-operation with G.R.R. Martin. The definitive heraldic authority for GoT, Ellio Garcia, has stated that this differentiation of field shape was stipulated by Martin himself: “George specified that Dornish shields are depicted as round in Westeros for purposes of heraldry, so suggested we do the same” (

Garcia 2016). In the fly leaves of

The World of Ice and Fire (

Martin et al. 2014), a spread of coats of arms uses the circular shield for all the Dornish examples. Purely circular (as opposed to oval) shield shapes are exceedingly rare in European heraldry, though Fox-Davies notes some examples belonging to, unsurprisingly, Moorish and Ottoman potentates (

Fox-Davies 1904, p. 6).

Mayer (

1933, p. 27) explains that in the Middle East, “When blazons came to be depicted on shields, the heraldic shields were usually round, and naturally so, because the Saracenic shield, as a piece of armour, was also round.”

In line with their reputation for exotic cruelty and venom, a further heraldic peculiarity with Dornish arms is that some depict quite macabre charges. In a move away from the lions, unicorns and stars of the north, the forbidding Dornish heritage is laid out in blazons such as:

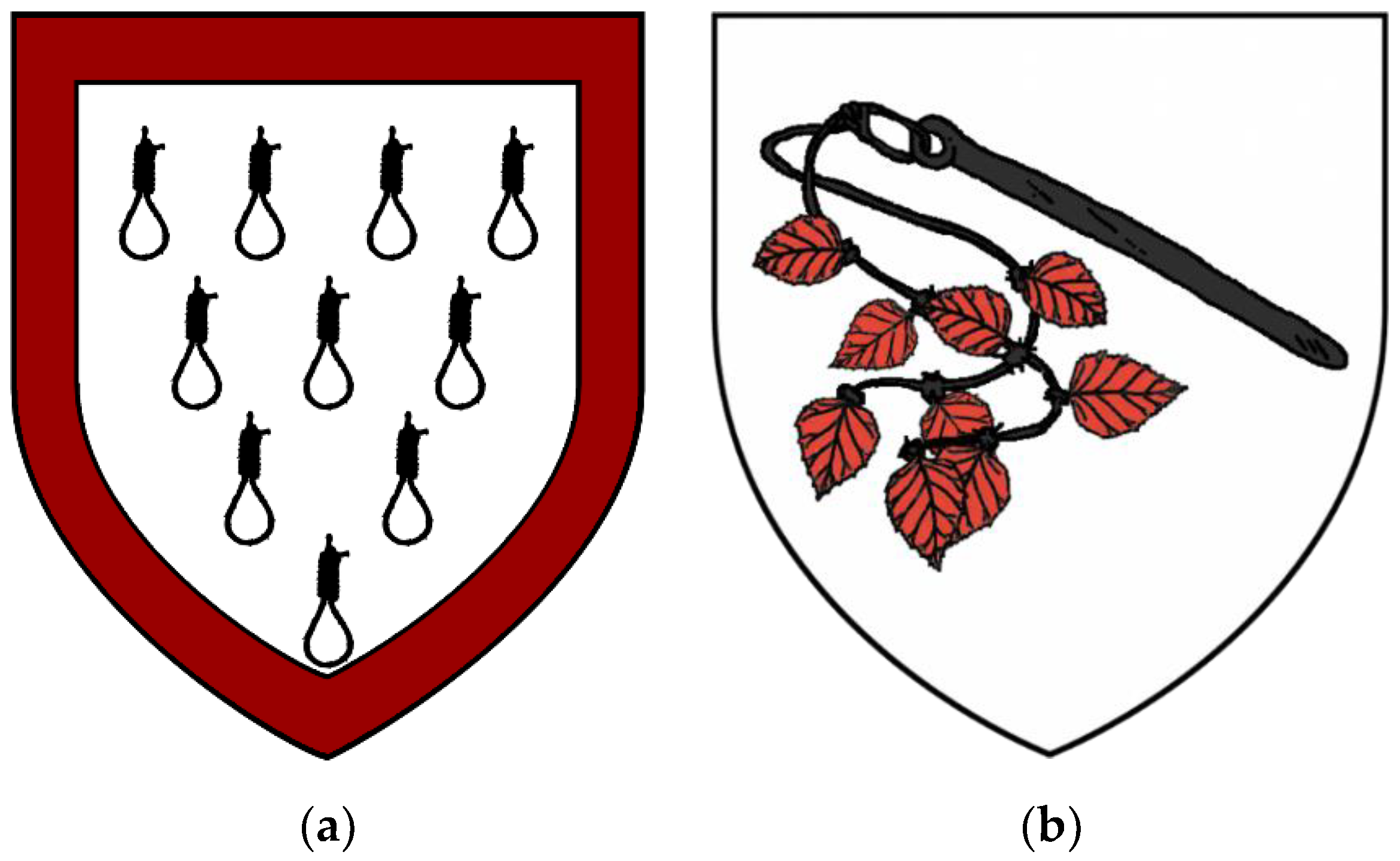

Gruesome illustrations are also a distinction of the only other part of the Seven Kingdoms that is at heraldic variance to the norm. Off the western coast of the continent lie the Iron Islands, inhabited by a Viking-type people based upon a martial culture of sea raiding. The Iron Islands are ruled by the Greyjoy family, whose house words “We do not sow” exhibit proud delight in eschewing agriculture and instead relying on taking what is needed from others. As would be expected from such a society, the coats of arms borne by some of the families in the archipelago show a tendency for the grisly (see

Figure 9):

House Drumm: A skeletal hand proper upon red (ibid.)

House Myre: 10 nooses black on white within a border of blood (ibid.)

House Sunderly: The drowned man being nibbled at by fish (q.v.)

Aside from these two distinct regions, there are some observable trends in the other more homogenous parts of the Seven Kingdoms. The arms of the northerners, who have a reputation for dour simplicity, tend to be less divided, less colourful and less decorative than their southern cousins, though this is not a hard and fast rule. While in the food basket region of the continent, known as The Reach, many family coats of arms depict references to agriculture or growth.

7. Illegitimacy

Birth status in regard to marriage is an important distinction for several key characters and plot arcs in the story.

14 Jon Snow’s mysterious heritage is one of the central pillars of the tale, as is the questionable legitimacy of Queen Cersei’s children. In the back-story history of Martin’s world, intra-dynastic clashes between legitimate (‘trueborn’) and illegitimate (‘natural’) offspring of King Aegon IV set up some of the political schisms that play out in the era of the main storyline.

Despite, or perhaps because of the importance of parentage, the heraldic system of GoT makes little accommodation for illegitimacy. Bastard sons, even of the nobility, do not have any automatic claim on either of their parents’ bloodlines (hence, even the application of a different surname). Thus, they have no right to these arms. There is then no need for a system of differencing for bastards because they are not armigerous to begin with, though they may (literally) bear their family arms as with any ordinary servant or retainer. There are, though, two possibilities that are described in GoT where illegitimate sons may come to possess their own differenced arms.

In the first case, a natural son can be legitimized by his father, as with the case of Ramsay Snow/Bolton. This situation would automatically allow the son to bear the family arms in full. However, some legitimized sons may then opt to devise their own coat of arms, either from their own wish to distinguish themselves, or perhaps out of pressure from legitimate siblings wishing to designate the new relative as remote from the ‘pure’ bloodline. In this case, there is no standard way of denoting illegitimate origins in the heraldic system. There are examples of colours being reversed, bends sinister, escutcheons and even hybrid animals being used to display differenced heritage.

15A second route for illegitimate males to make use of family arms is through knighthood. As noted above, knights may choose their own arms and a knighted bastard of noble stock might then elect (or be permitted) to utilize some variation or charge belonging to his family of origin. Examples of both of these possibilities being taken together also occur, with noble bastards being knighted in the first place and then legitimized at some point (see footnote above).

8. House Words

Of some importance to the families of Westeros are the mottos that they are associated with, known as ‘house words’. These fulfil a similar function to those in real world heraldry, being either rousing battle cries or “expressing some pious, loyal or moral sentiment and often playing on the name of the bearer or alluding to the device” (

Boutell and Brooke-Little 1973, p. 174). In the same way that coats of arms work as family brands in the story, these words are reputational and function in the manner of corporate slogans. Indeed, these mottos transcend the story and have been used by marketers to advertise the TV series. The words of House Stark, “Winter is Coming”

16, provided the name of the very first episode of the first season and the phrase has appeared on a variety of publicity material. The contrary version, “Winter is here”, was similarly used to promote the final season of the show.

There is no indication in either the books or the TV series as to how (or if) these words are incorporated into the heraldry of the fantasy world. For example, are they a formal component of a family crest or do they exist quite separately from any armorial bearing? The implication of a link between the coats of arms and the words is strong, since some slogans relate to the themes that are shown in the armorial designs.

17 It is therefore tempting to imagine them as appearing on a scroll beneath the coat of arms on a formal illustration, however there is no canonical evidence for this. In a medievalised world where literacy is the exception, there would in any case be no rationale for this. However, the importance that is attached to these words (attested to by the frequency with which they appear in the books and the script of the series) is indelibly linked to the question of family identity, so they are worth considering as linked to the same genealogical branding function of the blazonry.

9. Conclusions

The heraldry that is displayed in the GoT series is a product of some historical practices from the real world and the unique fantasy feudal system created by G.R.R. Martin. Future researchers of Martin’s work (and those of other fantasy authors) may like to explore specific fictional-historical comparison points, such as the lack of heraldic authorities in GoT, potential influences of English, Scottish or Continental heraldry or the relationship between coats of arms and family mottoes.

The dynastic branding role that heraldry performs in the GoT world is much stronger than it was in European history and is aided by the generally unaltered transmission of coats of arms across all male heirs, as well as their display by retainers and men-at-arms. Aside from their key role in the social framework of the stories, the heraldic motifs in GoT have become a central pillar of the franchise’s marketing. Just as GoT acted as a gateway to the fantasy genre for a new fan base, it has also brought heraldry from being a niche interest of an informed few to something that is appreciated by a mass audience. With a global viewership of hundreds of millions or even billions of people, several of these fantasy blazons are now arguably the most recognisable coats of arms in history.