1. Introduction

For the decade from 2005 to 2014, much research has focused on how sustainable development (SD) was incorporated in universities, especially because higher education institutions (HEIs) signed declarations, charters, and initiatives (DCIs) to demonstrate their top management’s commitment to sustainability in their system [

1,

2,

3].

By the end of the above-mentioned decade, more than 1000 universities had ratified DCIs, so HEIs were engaged in fostering transformative SD [

2]. Until now, there is a scarcity of investigation looking at the extent to which planning for SD can help HEIs to assess their performance and to determine whether the aims of their strategies and practices have been met [

3].

In Portugal, earlier research showed that embedding sustainability (the “top-down” approach) is insufficiently developed in Portuguese governmental institutions at university level [

4,

5].

In addition, the debate concerning HEIs’ role towards SD has recently begun [

6,

7] and the few events organized so far were mostly dedicated to the environmental perspective [

8]. Moreover, SD policies are key factors for a university’s successful engagement concerning sustainability matters and indicate how active they are in this field [

8]. One of the levels of sustainability integration in higher education (HE) is at the institution level within the macro HE public policy system [

9]. Nonetheless, no attempt has been made to assess how Portuguese public HEIs are integrating education for sustainable development (ESD) at policy and strategy levels, and how the documental analysis of HEI plans, reports, and strategies can be a useful approach to evaluate SD integration in universities. The research question is to what extent ESD has been integrated in the Portuguese public HEIs’ policies within the United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (UN DESD) 2005–2014, and consequently to provide insights about their (best) practices.

The purpose of this study, conducted within the timeframe of the United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (UN DESD) 2005–2014, is to evaluate the extent to which ESD has been integrated in Portuguese public HEIs through the treatment and analysis of the universities’ (i) strategic activity plans (PEs), strategic plans and development plans (PDEs), and activity and operational plans (PAs); (ii) activity reports (RAs), strategic activity reports, sustainability reports (RSs), and annual financial reports (RCs); as well as (iii) responsibility and assessment frameworks (QUARs) (QUAR (“Quadros de avaliação e responsabilização”) illuminate the universities’ mission, their strategic and operational goals, their key performance indicators and aims, as well as the financial and human resources available to facilitate moving towards targets and the achievement and effectiveness of such targets).

These plans relate to what HEIs are planning to accomplish in the short or medium term, depending if it is an annual or a quinquennial program, and the reports relate to what has been achieved from within the plan or beyond the plan.

1.1. Universities’ Commitments to Implement ESD

In October 1990, the Taillores Declaration was signed by 30 universities worldwide. This early declaration recognized the fundamental role that universities should have in the future concerning the implementation and dissemination of sustainability:

Universities have a major role in the education, research, policy formation, and information exchange necessary to make these goals possible. Thus, university leaders must initiate and support mobilization of internal and external resources so that their institutions respond to this urgent challenge.

Later, the 1992 Conference of European Rectors at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED), which took place in Rio de Janeiro, made an urgent appeal for the involvement of universities in SD and for an inclusive strategy for building a sustainable future which is equitable for all. In Europe, this declaration was signed by more than 320 HEIs in 38 countries [

11].

In 1994, the Copernicus program developed its own strategy on the ten action principles to preserve the environment and promote SD, which was signed by 196 universities [

12]. The universities’ role was defined as follows:

It is consequently their [universities] duty to propagate environmental literacy and to promote the practice of environmental ethics in society, in accordance with the principles set out in the Magna Carta of European Universities and subsequent university declarations, and along the lines of the UNCED [Rio Conference in 1992] recommendations for environment and development education.

In May 2005, at the European Higher Education Ministerial Conference held in Bergen, Norway, there was a strong reference to SD for the first time. It was said, when describing the Bologna Process, that “our contribution to achieving education for all should be based on the principle of sustainable development and be in accordance with the ongoing international work on developing guidelines for quality provision of cross-border higher education” [

11].

At the United Nations Rio + 20 conference in 2012, the commitment of Higher Education Sustainable Initiatives (HESI) was announced, including teaching sustainable development concepts, encouraging research on SD, making campuses more sustainable, and involving the community in all these actions, committing institutions to concrete results and actions [

13].

Additionally, the UNESCO World Conference on ESD, held in Aichi-Nagoya (Japan) in 2014, adopted a declaration and a call for urgent action to further strengthen and scale up ESD, where HEIs have a special role [

14], namely in transforming societies and in key aspects of citizenship.

In the post-2015 DESD agenda, these characteristics were emphasized and linked to the establishment and achievement of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) defined by the United Nations in 2015 [

15]. In fact, the seventeen SDGs were set placing education at the heart of the promotion of SD [

16], proposing a HE field that is greatly influenced by the global sustainability agenda as well as by the management education requirements [

17].

From a worldwide survey linked to the seven dimensions of the recognized university system [

2], it was concluded that there is a strong relationship between SD commitment, integration, and the signing of DCIs, showing that there are two HEI clusters:

“the ones at the forefront, which show high commitment, have signed a declaration or belong to a charter, and have engaged in implementing SD; and those HEIs, which are lagging in commitment, implementation, and declaration signing”.

1.2. A Worldwide Integration of ESD in Universities’ Strategies and Policies

HEIs can implement ESD in several dimensions in order to be as holistic as possible. The more common dimensions are: (1) Institutional framework (i.e., the HEIs’ commitment); (2) campus operations; (3) education: courses on SD, programs on SD, transdisciplinary curricular reviews, including “educate-the-educators” programs (which promote competencies in EDS to enable an integrated approach of knowledge, procedures, attitudes, and values in teaching through multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary teams [

18]); (4) research; (5) outreach and collaboration; (6) SD through on-campus experiences, working groups, policies for students and staff, among other practices; and (7) assessment and reporting [

2,

19].

Universities worldwide are experiencing an increasing trend towards responding to the need for sustainability and various knowledge gaps [

20], as well as collaborating and contributing to the generation of sustainability values, attitudes, and behaviors within future regenerative societies [

21]. Regarding some European countries, access to quality education is so critical for development [

22] that the European Parliament has continuously called for the allocation of its budget to investment in this sector [

23]. Universities can use low-carbon campuses as living laboratories in shaping the leaders of future sustainability thought. Many HEIs are already involved in mainstreaming the environment and sustainability into their curricula, training, research, and community engagement activities [

24].

From the results of surveying a sample of universities from Germany, Greece, United Kingdom (UK), United States of America (USA), South Africa, Brazil, and Portugal [

8], it was reported that there is a widely-held belief that SD policies are essential for HEIs to successfully engage in matters related to sustainability and that such policies show how active they are in this field. Therefore, a university must be considered active and have formal policies on SD as a pre-condition for successful sustainability efforts [

25].

Considering HEIs’ degree of commitment to and institutional trust in sustainability in USA, it was noted [

25] that universities are uniquely positioned as knowledge disseminators, behavior consolidators, and idea innovators towards a resilient and impartial society, as they offer a superior learning environment and campus lifestyle experience to initiate a more holistic understanding and contemplation around sustainability.

Therefore, HEIs have embedded sustainability initiatives into their core activities, curriculum, research, community, and operational, to respond to the worldwide transformation towards a sustainable future [

26].

1.3. An Implementation Research Gap in Portuguese Public Universities

Despite international studies on ESD in European universities ,which provide best practices and examples [

27,

28,

29], this area represents a gap in higher education research in some countries (e.g., Czech Republic, Poland, Spain) [

30,

31,

32] and the insufficient number of studies in Portugal concerning strategic environmental assessment was emphasized [

33].

These detailed, national-scale studies can contribute to a better evaluation of HEIs’ levels of effort and success in contributing towards encouraging worldwide sustainable development and the role of academia in meeting this purpose [

17].

In 2007, which falls within the decade 2005–2014, the Portuguese Government passed the Decree-Law 242/2007, which transposed the Directive 2001/42/EC, promoted the effective institutional autonomy of universities [

34], and facilitated environmental assessments regarding the effects of certain plans and programs [

32].

In comparison to other European countries, Portugal was far behind in externally-oriented activities aimed at building capacity within local communities to promote SD, and Portuguese HEIs were classified as “laggards” and/or “late majority” in integrating SD in education, in research on sustainability, and in inclusive development in universities, in particular when compared with other Southern European countries [

6].

Despite having signed Declarations and/or Charters, Portuguese public HEIs may or may not have implemented SD, while others that did not sign any commitment have engaged in implementing sustainability.

Regardless of previous research, it is important to comprehend how Portuguese public universities are applying ESD at policy and strategy levels (between 2005 and 2014), since no attempt has been made to evaluate their commitments and practices in a systematic and detailed way.

2. Methodology

2.1. University’s Sample of Universities

Considering the UN DESD 2005–2014, the University Higher Education Institutions (UHEI) sample was based on the effective members of the Portuguese University Rectors Council (CRUP) during the analysis period (2005–2014), which correspond to all public universities. These HEIs comprised: UAc—University of the Azores [

35], UMinho—University of Minho [

36,

37,

38], UAb—Universidade Aberta [

39,

40], UP—University of Porto [

41,

42], UAlg—University of Algarve, UTAD—University of Trás os Montes e Alto Douro [

43], UÉ—University of Évora [

44,

45], UBI—University of Beira Interior [

46,

47,

48,

49], UC—University of Coimbra [

50,

51], UTL—Technical University of Lisbon, UL—University of Lisbon, ULisboa – Universidade de Lisboa [

52], UNL—NOVA University of Lisbon [

53], UA—University of Aveiro [

54], and UMa—University of Madeira.

In July 2013, two large public universities, UTL and UL merged to increase their scale, attract a larger volume of students, capitalize on the prestige of their faculties, and help them to achieve a greater leadership role in the European context. ULisboa “brings together various areas of knowledge and has a privileged position for facilitating the contemporary evolution of science, technology, arts and humanities [

52]”

These public HEIs, together with ISCTE-IUL—University Institute of Lisbon [

55] and UCP—Universidade Católica Portuguesa [

56], represent the core of the Portuguese national higher education system [

57].

The creation in 1979 of CRUP—Portuguese University Rectors Council, a Portuguese university associative structure, constituted a major step in the decentralization of the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Higher Education (MCTES) responsibilities for Higher Education [

58]. One of its major working areas is guaranteeing universities’ coordination and their representativeness, while ensuring their autonomy [

57] (see

Appendix A,

Figure A1).

Despite the researchers’ efforts, it was not possible to obtain supplementary documentation from all the universities that belong to CRUP.

The final UHEI sample turned out to be 14 public universities and some had similar characteristics such as geographical location, number of students, and campus area (see

Table 1).

Confidentiality was ensured by allocating an alphanumeric identification to each public university (HEI_01 to HEI_14) so that the names of the respective institutions did not appear in the publication findings and results.

2.2. Data Collection and Time Frame

This study used a qualitative approach [

59] and a detailed content analysis method.

Institutional documents were analyzed to:

- (a)

Find out how each public HEIs integrated sustainability, whether under any DCI or not;

- (b)

Discover the commitment of each public university to SD;

- (c)

Provide insights about (best) practices in implementing ESD at public universities.

The following types of documents corresponding to the period 2005 to 2014 (i.e., a 10-year period; see

Table 2) for each HEI, were:

Plans (PAs, PDEs, and PEs),

Reports (RAs, Strategic Activity, RCs, and RSs), and

QUARs.

The data were collected between 1 January 2015 and 30 June 2016, through public university websites, email contacts, and some UHEIs’ documentation centers, mainly due to their willingness to participate in this study. After the data collection period, no further documentation was considered despite its availability on websites.

Eventually, universities might publish this type of documentation, but it was not available for the researchers during the time frame of the collection period despite their efforts.

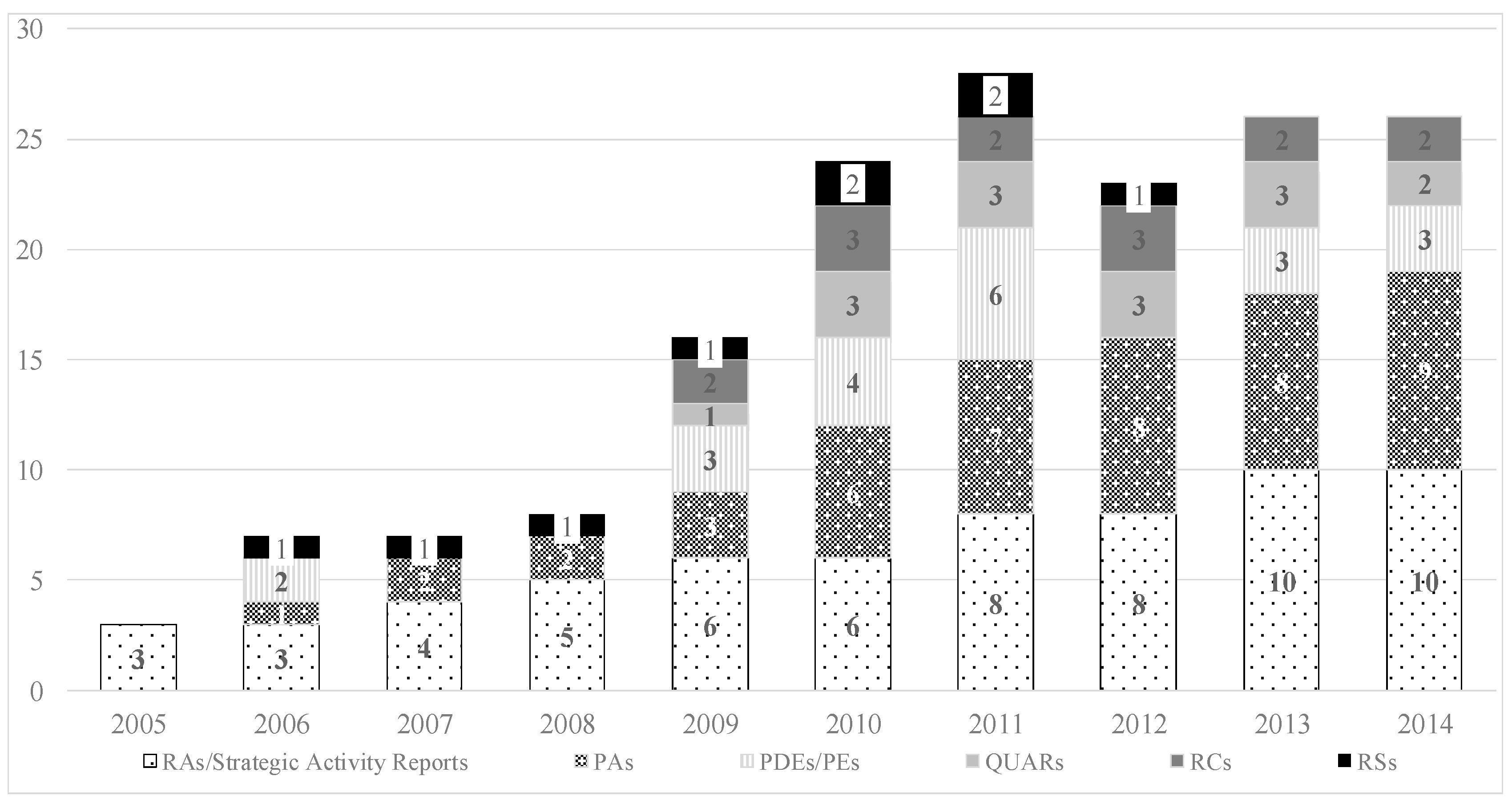

Overall, 168 documents from the 14 public universities were gathered for treatment and analysis.

2.3. Documental Approach of Public Universities’ Sustainability Integration

HEI_01, HEI_02, HEI_03, HEI_04, HEI_05, HEI_06, and HEI_07 contributed 85% of all the collected documents (see

Appendix A,

Figure A2). Even though seven universities provided the vast majority of the institutional document sample, the aim was to find out how each public HEI implemented sustainability and their commitment to SD, and to provide insights about best practices.

The year 2011, which was the year in which Portugal came under the international financial assistance program, corresponded to the highest number of documents gathered. This may be explained by the increased need to support financial reports with long-term planning.

Considering the first half of the UN decade 2005–2014, corresponding to the period from 2005 to 2009, concerning document type, PAs, PDEs, PEs, RAs, Strategic Activity Reports, and RSs represented 83% of all the documents.

In the second half of the period 2010–2014 there was not much difference (80%). RS accounted for 10% and 4% of the collected documents in the first and second half of the decade 2005–2014, respectively, and were published either by HEI_01 or HEI_03. From the second half of the DESD, around 33% and 43% were RAs/Strategic Activity Reports and PAs/PDEs/PEs, respectively. There seems to have been more activity planning than reporting, which might not be so true if RSs and RCs were combined.

The scenario was quite different when analyzing the documentation obtained in the period 2005 to 2009, as it seems there was more reporting and less planning. Adding RC (5%) and RS (10%) accounted for almost 66% of reporting activity altogether (see

Figure 1).

From 2005 to 2014, almost 80% of the collected documentation was related to activity planning or reporting (see

Appendix A,

Figure A2). Despite the few sustainability reports published by the public HEIs (only two did so, UMinho and UP), they are of utmost importance for the content analysis concerning sustainability implementation because they were published during the UN Decade.

2.4. Documental Sample Data Treatment and Analysis

The data treatment and analysis were divided in a four-step approach:

- 1.

When collecting documents, few universities possess documents such as RC and QUAR. Since this is the case, this constitutes a drawback in the study to (better) assess policies and strategies at university level, so it was the first cut in the treatment phase. From an overall sample of 168 documents it was reduced to 139 (the “major documents”) (see

Table 3). From here, the data treatment was made.

The documents were selected, taking into account neither type nor university origin, to be treated and analyzed considering the highest frequency of keywords (see

Table 4) in the defined coding system obtained in the content analysis of a previous study [

4]. The following results were, in descending order, “Integration or intervention or implementation” (the main reference found), followed by “Environmental Education” (these two were the main references), then “University Higher Education or University” and “Sustainability (ies) or sustainable (s)”.

- 2.

The content was then analyzed in a systematic review, where a node corresponds to a public UHEI and each subcategory to a type of document. This coding technique was used to analyze the documents. As coding is a process to generate categories, the analysis started by using descriptive coding, where words and sentences from document transcripts were labeled using relevant words or phrases [

60].

- 3.

Other nodes were built hereinafter as “Dimensions” relating to the recognized university system [

2]:

Institutional framework (Dimension #1);

Campus operations (Dimension #2);

Education (Dimension #3);

Research (Dimension #4);

Outreach and collaboration (Dimension #5);

SD through on-campus experiences (Dimension #6); and

Assessment and reporting (Dimension #7).

The themes where ESD has been implemented in HEIs were organized in dimensions and corresponded to subcategories. Each subcategory was called a sustainability implementation action (SIA) within the content analysis methodology [

59]. In the end, the coding system was rearranged again based on the number of codified references, and the sustainability implementation actions (SIA) renamed, which were obtained after the treatment and analysis of the major documents.

The process consisted of organizing the disclosed data into distinct categories and/or new nodes, through a classification.

Every time a document was treated and analyzed; the code was modified to reflect the correct adjustments. This was; therefore, a collaborative process based on diversified readings before treating and analyzing the available documentation—139 documents from the 2005 to 2014 period—from which at least three adjustments were made to some of the items (a suggested procedure [

61]).

The dimensions of the recognized university system [

2] were used, as well as the themes associated with each aspect as a proxy of integration sustainability in each HEI. This was a cataloguing method in which an organized codebook was produced.

Lastly, all data contributed to the definition of a country profile for the implementation of sustainability in the HE sector.

For the qualitative content analysis, NVIVO (version 11) software (QSR International Pty Ltd, Victoria, Australia) was used [

62].

3. Results

3.1. The Sustainability Implementation Actions in Portuguese Public HEIs

Overall, considering the seven dimensions [

2], 66 themes were found as sustainability implementation actions (see Figure 3).

All Portuguese public universities seemed to have been implementing sustainability and more than 50% of actions were not exclusive to a single UHEI (see

Table 1). Among the seven dimensions, “campus operations,” “outreach and collaboration,” and “SD through on-campus experiences” represented almost two thirds of the total sustainability implementation actions (see

Table 5 and

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). It; thus, seems that these were the main dimensions by which the Portuguese UHEIs implemented sustainability through strategies and policies.

Considering the number of sustainability implementation actions (see

Table 5) throughout the HEIs, the top three were:

SD partnerships with other society stakeholders (#6), which are linked to “outreach and collaboration”;

Policies that promote SD for students and staff (#5), which are linked to “SD through on-campus experiences”; and

Signature of DCIs within SD, ESD, or sustainability during United Nations (UN) DESD 2005–2014 (#5), which is linked to “institutional framework”.

Taking into consideration the treated and analyzed documents, universities’ actions relating to ESD seemed to have been taken in “isolation” and were not integrated in a whole institution approach. Each HEI acted according to a tank of actions—“think tank” (see

Figure 4).

Each university may have taken one, or more than one, path to integrate their strategies and policies on sustainability, but it seems any integration did not keep up with the simultaneous pace of action.

The findings in Portuguese public HEIs also suggested that identical SD integration during the DESD 2005–2014 could have occurred for different reasons:

3.2. DCIs and the Commitments of the Portuguese Public Universities

As of 1 February 2018, 502 institutions had signed the Taillores Declaration. However, in 1990, the NOVA University of Lisbon (UNL) was listed as the only Portuguese signatory HEI, according to the Association of University Leaders for a Sustainable Future [

10].

The findings indicate that UNL was deeply involved in the outreach and collaboration and institutional framework Dimensions through the following sustainability implementation actions: (1) Joint degrees with other universities, and (2) the existence of policy and a strategic plan for implementing SD in the University.

Besides having signed the Taillores Declaration, UNL belonged to the Copernicus Charter in 1994. According to these documents’ principles, sustainability should be incorporated in a university’s faculties, departments, and other entities. The signature by UNL of both the Declaration and the Charter signaled an official commitment to SD by this university.

Nevertheless, other Portuguese HEIs also signed the Copernicus Charter, such as UTL, UP, UMinho, UL, and UCP. The results concerning UMinho and UP will be shown in

Section 3.3.

The results indicate that like UNL, UTL was involved in the outreach and collaboration Dimension through the creation of joint degrees with other universities.

The overall results indicate that UNL and UTL (which, after the merger with UL, resulted in ULisboa), representing almost 30% of all HEIs’ students, were both involved in the creation of a joint degree as mentioned. Nonetheless, it cannot be assured through any DCIs that this fact is due to their commitment to SD.

3.3. Commitment to SD of Universities with Sustainability Reports (RS) and DCI

UMinho and UP were the only two out of the six Portuguese Copernicus Charter signatories that developed the “assessment and reporting” through sustainability reports. RSs enable organizations to take into consideration the impact of a wide range of sustainability issues, allowing them to be more transparent about the risks and opportunities [

63].

Owing to UMinho’s strong cultural activity, this HEI uses the Global Report Initiative (GRI) as guidelines for sustainability reporting (2010 and 2011) and improved its methodology in 2012/2013 [

36] (pp. 113–114) by including a new (cultural) dimension [

37].

According to the RS from 2011 [

36] (pp. 113–114), globally UMinho is on its way to sustainability considering economic, environmental, and social indicators, namely due to its direct and indirect impact in the local economy. As an example, the production of dangerous solid waste had been reduced by 2.5 ton from 2009 to 2011 and the 2015 emissions of CO

2 equivalent (ton) × 1000 ton. CO

2 equivalent were 16 in a campus area of 40 ha (see also

Table 1).

Nevertheless, environmental performance should be improved to reinforce UMinho’s commitment to sustainability, according to the University Rector (see

Table 6). From the analysis of the documents, the sustainability implementation actions of UMinho were mainly based (almost 50% of the total number of UMinho’s initiatives) on the “campus operations” Dimension, either through (1) plans to improve energy efficiency; (2) energy efficient equipment; (3) policies and activities to reduce paper consumption; (4) plans to improve the management of waste; or (5) green purchasing from environmentally and socially responsible companies. There were also actions based on “institutional framework” through the existence of policies for implementing SD in the university.

The National Strategy for Ecological Public Purchases by Resolution of the Council of Ministers (i.e., a government decision) was found to be used by UMinho concerning green purchasing as well as the Energetic Efficiency Program in Public Administration (Eco.AP) regarding energy efficiency.

There are some best practices in this university seen in the Institute of Science and Innovation for Bio-Sustainability (IB-S) and Landscape Laboratory.

The first Portuguese HEI that used GRI guidelines was the Engineering Faculty of University of Porto (FEUP) in 2006, and from 2008 onwards; however, the RS are only related to the faculty and not the whole university. The GRI model was used to assess, monitor, and report sustainability with a focus on the academic community, operations, teaching, and impact on society, which seems to have some similarities with the Sustainability Assessment Questionnaire (SAQ).

It should be noted that FEUP is concerned with all Dimensions and not only environmental ones [

41].

These sustainability implementations actions by the University of Porto seem to have been based on many different Dimensions. Concerning the “campus operations” Dimension, actions seem to occur through (1) sustainable landscaping; (2) policies and activities to reduce paper consumption, such as e-communications or double-sided copying; (3) renewable energy usage, through the implementation of photoelectric performance systems; and (4) energy-efficient equipment.

There were also actions relating to “SD through on-campus experiences,” through (1) policies that promote SD for all students and staff; (2) sustainable practices for students; (3) a SD working group with members from different departments; (4) SD efforts that are visible throughout the campus; and (5) student participation in SD activities, such as collaboration in multiple social solidarity projects.

Concerning the “assessment and reporting” Dimension, UP seemed to have implemented sustainability through (1) RS, and (2) the assessment of SD issues using SD integration instruments and tools within the University through the total management system (SGT); the implementation of consumption monitoring routines (namely, student participation in SD activities through collaboration in multiple social solidarity projects, and the disclosure of RS); and some best practices (namely the optimization of equipment and system schedules through the centralized technical management system (SGTC) and the “paper calculator” software developed by the “Environmental Paper Network” [

42] and G.A.S.PORTO - Oporto Social Action Group).

There seems to have been be special care taken regarding the publication of RS by UP/FEUP between 2008 and 2011 and the integration of instruments and tools to assess SD issues.

Regarding the “outreach and collaboration” Dimension, the action related to the involvement of academic staff in voluntary advisory activities in SD seemed to be one of the initiatives.

The UP’s “institutional framework” demonstrates a commitment to the inclusion of SD in the vision, mission, goals, and objectives of the University.

The extent to which UMinho and UP were able to integrate sustainability into their strategies or policies can be found through the actions organized in themes. From there, not only did these HEIs seem to have implemented sustainability internally through campus activities and on-campus experiences, but they also did it through outreach and collaboration (external routes). Both HEIs were committed to SD within their institutional framework and deeply involved in the assessment and reporting Dimensions.

3.4. Commitment to SD of Universities without DCIs or RS

There were universities that had not signed any DCI or published any RS but were committed to SD and implemented sustainability actions.

Many HEIs used the Energetic Efficiency Program in Public Administration (Eco.AP) regarding energy efficiency in the “campus operations” Dimensions (which was the case of HEI_04, HEI_05, HEI_06, and HEI_08; see

Table 5 and

Figure 5).

The implementation of “SD through on-campus experiences” was found in many of the studied universities, as well as other sustainability implementation actions, such as policies that promote SD for all students and staff; in these areas, SD efforts were visible throughout the campus and some best practices were found (e.g., “knowledge sharing” and a “cultural training program”).

Regarding “outreach and collaboration,” the actions found were: (1) SD partnerships with other society stakeholders (HEI_08 and HEI_13), and (2) academic staff involved in voluntary advisory activities in SD (e.g., HEI_08).

One of the universities played a role in the environmental area with the creation of a sustainable campus that resulted from a partnership with GALP Energia (a Portuguese energy company) and others. Another initiative by this university involved the creation of synergies between sports and health, involving a stadium in the promotion of common projects with schools (best practice). Moreover, another university had a role in the promotion of sports and adapted sports, like canoeing, sailing, and adapted sailing, as well as in the creation of research centers and/or associated laboratories (hosting researchers from other universities).

Concerning the “education” Dimension, some HEIs created study programs (e.g., Masters—Sustainable Energy, Environment and Sustainability, PhD—Sustainable Energy Systems, which was financed by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) program in 2007 [

64], Global Change (Climate Change and Sustainable Development Policies), Social Sustainability and Development) in areas such as energy, global change, sustainability, environment and sustainability, social sustainability and development, or a combination of these terms.

In one university, the gathering of professors from different faculties, departments and research and development (R&D) units was a path to promote interdisciplinary collaboration in teaching and development. This leverages talent and financial resources and creates awareness on sustainability issues, namely in the areas of energy and SD.

At one of the studied universities, the commencement of a doctoral program in the academic year 2010/2011, which is an interdepartmental program between two departments, is a good example of a university offering education with a transdisciplinary focus. The sustainability implementation action was evidenced by course syllabuses of courses or programs on SD.

In the “research” Dimension, one university showed the existence of patents in the field of SD.

Towards a country profile for Portugal for the implementation of sustainability in Higher Education, on the basis of their likelihood in the “think tank” (

Figure 4), the sustainability implementation actions were classified according to the quartiles (see

Figure 5) for the overall number, for the dimensions of campus operations, outreach and collaboration, and SD through on-campus experiences (the top three).

Group I corresponds to the first quartile (one to two actions overall) including six universities

Group II corresponds to the second quartile (three actions overall) including two universities

Group III corresponds to the third quartile (four to five actions overall) including three universities

Group IV corresponds to the fourth quartile (more than five actions overall) including three universities

Figure 5 is a box plot. Considering the top three Dimensions, the first, second, and third quartiles overlapped. This means that 75% of the Universities have taken this path to implement one or two sustainability actions. For the Dimensions education and research combined, four actions were taken in 75% of the universities.

Universities seemed to have integrated SD through multiple and simultaneous actions at their own rhythm and pace.

These findings showed no apparent relationship with the number of students or campus area because the results followed all of the steps explained in

Section 2.

4. Discussion

Many European universities have integrated SD into their academic systems. There are also important connections between commitment, integration, and the signing of a DCI [

2], relating to the leverage of values, attitudes, and behaviors within present and future regenerative societies [

21].

The results presented in this paper show that if a university signs a declaration or a charter it seems to lead to a commitment to SD, no matter how narrow it may be, partly through the implementation of several sustainability actions. This was the case of at least four universities in Portugal (UP, UMinho, UNL, and UTL). However, sustainability implementation was present in all the other studied universities.

During the DESD 2005–2014, the results show that Portuguese public universities implemented sustainability through diverse and multiple actions, mostly by (i) establishing partnerships with other society stakeholders; (ii) implementing policies that promote SD for all students and staff; (iii) signing DCIs within SD, ESD, or sustainability during the UN decade; and also (iv) by promoting best practices.

Aleixo et al. (2018) and Arroyo et al. (2017) [

65,

66] refer not only to the importance of putting into practice universities’ transformative role in SD by including sustainability in an institution’s agenda, strategies, and best practices to promote said agenda, but also by the institution remaining engaged in the field despite facing the usual implementation problems, varying from restricted resources to lack of trained staff [

3], deficient organizational structure, inertia, and resistance [

66].

Based on the evidence of sustainability implementation actions, concrete proof for whether universities were committed to SD, a four-group classification was built to measure how far the policies and strategies were integrated. It showed that despite some universities having done more than others regarding the dimensions [

2], all of them were engaged in SD implementation at their own pace. This is in line with published literature about Portuguese HEIs [

65] that recommend a further development of sustainability initiatives for several Portuguese universities.

More than 50% of the actions in Portuguese public universities were not exclusive to a single university. Additionally, the “campus operations,” “outreach and collaboration,” and “SD through on-campus experiences” Dimensions represented about two thirds of the total sustainability implementation actions. Therefore, the way by which ESD has been integrated in Portuguese public universities within the United Nations Decade of Education for Sustainable Development 2005–2014 seems to have been a bottom-up approach. A university must have policies on SD which are in line with [

18] when mentioning them as a pre-condition for successful sustainability efforts.

Sustainability reports are a suitable tool for universities concerning SD incorporation, but this is not a common practice [

1]. RSs are a tool increasingly used by accreditation bodies, governments, and students [

67]. This seems to correspond to the presented findings, as UP and UMinho were the only two universities that produce RSs.

RSs have a large potential for the process of sustainability development integration in HE, namely for organizational change, stakeholder engagement processes in RS, link between RS and general sustainability management, and relationships between existing reporting indicators, tools, and management standards [

68]. Thus, the development of RSs at universities in Portugal should be widely encouraged. Aleixo et al. (2018) [

66] mention that UMinho is in a SD implementation phase, due to university sustainability reports, and so this university seems to be an early adopter.

From this study’s findings, best practices regarding green campus procedures were found in many of the studied universities. Indeed, campus operations are among the more commonly applied ESD domains in universities ([

9,

66,

69]. At this point, it should be said that the data used for this characterization can be underestimated and differences between institutions may be attributed to cataloguing methods, lack of documentation, or a less systematic search where the terms (e.g., “green campus procedures”) were not formally stated.

Regarding the “outreach and collaboration” Dimension, namely “partnerships with other civil stakeholders (e.g., Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), municipality, regional government, etc.),” many best practices were found in Portuguese public universities (e.g., UBI and UA) which seems to be not quite in line with [

70], who reported that Portugal was far behind in externally-oriented activities aimed at building capacity within local communities to promote SD.

Implementation actions relating to the “education” and “research” Dimensions were not intensely found, which is in accordance with [

6] that classified Portuguese universities as “laggards” and/or “late majority”.

There may be significant advancements in the operational dimensions of a university, in curricular and educational transformation as well as in research and outreach activities [

71,

72], but in most cases, sustainability has not yet become an integral part of the university system [

73].

Notwithstanding its improvement in recent years, the requested paradigm change from un-sustainability to sustainability in university systems is not yet fully identifiable [

74].

Even so, Portuguese universities show good examples of sustainability interdisciplinary curricula, particularly at the post-graduate level. The breadth and interconnectedness required for implementing the SDGs make it evident that experts from different subjects and sectors must work together to deliver the goals [

16], as well as that future research should concentrate on the challenge of measuring and assessing the differing conceptualizations of “sustainability” within what the curricular offers [

68,

75].

Many universities are already involved in sustainability through the curricula, training, research, and community engagement activities [

24]. This difference may be attributed either to the localization of public universities and/or the lack of documentation from some universities.

Communication is a core function of higher education [

9]. In terms of ESD coordination and communication at the national level, it should be mentioned that there is an existing gap arising from the lack of ESD at governmental policy and strategy levels either by the Portuguese Government or the Ministry of Public Universities [

4,

5].

Nevertheless, there has been effective coordination between universities regarding national and international programs like Eco.AP and the MIT 2007 Program.

A detailed and deep content analysis of several documents, namely the strategic and activity plans, showed that, during the UN DESD 2005–2014, Portuguese public universities implemented sustainability actions in many different ways and Dimensions when compared with earlier studies.

Nevertheless, the initiatives found in each university were not integrated within a whole-school approach [

19]. A whole-university approach for embedding sustainability in the university is fundamental for a transformation in learning and education for sustainability with interdisciplinary collaboration between academics. This is critical for promoting the needed transformation in students to become agents of a sustainable future [

9,

25].

Usually in these types of studies, where a profile of a region is drawn, data are gathered only by questionnaire or interview survey [

75]. This systematic analysis of gathered documental data was the basis for the characterization of a country profile for Portugal for ESD implementation in universities and allowed a detail analysis usually not possible through surveys, in which response rates are often low.

Based on the searched and identified actions, a “think tank” (a tank of actions) may be widened, and a cooperation network—SharingSustainability4U—established with a list of best practices and areas for sustainability improvement, irrespective of the university’s dimensions. Single universities may support and benefit from being a node in a university network for sustainability [

76]. Collaboration and support among universities are key success factors as universities have not implemented sustainability at the same pace, to the same extent, and in the same Dimension(s). The Portuguese University Rectors Council can have a key role as mediator or even coordinator of this network.