The Corporate Sustainability Strategy in Organisations: A Systematic Review and Future Directions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Bibliometric Analysis

4. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Engert, S.; Rauter, R.; Baumgartner, R.J. Exploring the integration of corporate sustainability into strategic management: A literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 2833–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.D.P. Configuration of External Influences: The Combined Effects of Institutions and Stakeholders on Corporate Social Responsibility Strategies. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 102, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, R.J.; Ebner, D. Corporate sustainability strategies: Sustainability profiles and maturity levels. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Marrewijk, M.; Werre, M. Multiple levels of corporate sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcano, L. Strategic Management and Sustainability in Luxury Companies. J. Corp. Citizsh. 2013, 2013, 36–54. [Google Scholar]

- Gladwin, T.N.; Kennelly, J.J.; Krause, T. Shifting Paradigms for Sustainable for Implications Development: And Theory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 874–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P. Is Strategic Management Ideological? J. Manag. 1986, 12, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Fredrickson, J.W.S. Are you sure you have a strategy? Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2001, 15, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronda-Pupo, G.A.; Guerras-Martin, L.Á. Dynamics Of The Evolution Of The Strategy Concept 1962–2008: A Co-Word Analysis. Strateg. Manag. J. 2012, 33, 162–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, J.G.; Stead, W.E. Sustainable strategic management: An evolutionary perspective. Int. J. Sustain. Strateg. Manag. 2008, 1, 62–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, J.G.; Stead, E.W. Management for a Small Planet: Strategic Decision Making and the Environment, 2st ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- World Economic Commission on Environment and Development. Available online: https://idl-bnc-idrc.dspacedirect.org/bitstream/handle/10625/152/WCED_v17_doc149.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 22 June 2018).

- Bansal, P. Evolving sustainably: A longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P. The corporate challenges of sustainable development. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2002, 16, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Towards a dynamic theory of strategy. Strateg. Manag. J. 1998, 12, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.; Koc, W. Development of a systematic framework for sustainability management of organisations. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 1255–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, A.; Costa, R.; Levialdi, N.; Menichini, T. Technological Forecasting & Social Change Integrating sustainability into strategic decision-making: A fuzzy AHP method for the selection of relevant sustainability issues. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 139, 155–168. [Google Scholar]

- Batista, A.; Francisco, A. Organizational Sustainability Practices: A Study of the Firms Listed by the Corporate Sustainability Index. Sustainability 2018, 10, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rok, B. Transition from Corporate Responsibility to Sustainable Strategic Management. In Corporate Social Responsibility in Poland; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Perrott, B. The sustainable organisation: Blueprint for an integrated model. J. Bus. Strategy 2014, 35, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, R.J. Managing corporate sustainability and CSR: A conceptual framework combining values, strategies and instruments contributing to sustainable development. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 258–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engert, S.; Baumgartner, R.J. Corporate sustainability strategy—Bridging the gap between formulation and implementation. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 113, 822–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiningrum, T.S. Strategic Planning: Shaping Organisation Action Or Emerging From Organisational Action? J. Bus. Strategy Exec. 2012, 5, 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Guohui, S.; Eppler, M.J. Making Strategy Work: A Literature Review on the Factors Influencing Strategy Implementation. In Handbook of Strategy Process Research; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bonn, I.; Fisher, J. Sustainability: The missing ingredient in strategy. J. Bus. Strategy 2011, 32, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abele-Brehm, A.E. (Ed.) Wohlbefinden: Theorie, Empirie, Diagnostik; Juventa-Verlag: Weinheim, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- White, H.D.; McCain, K.W. Visualizing a discipline: An author co-citation analysis of information science, 1972–1995. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1998, 49, 327–355. [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan, K.M.; Kane, M.; Trochim, W.M.K. Evaluation of large research initiatives: Outcomes, challenges, and methodological considerations. New Dir. Eval. 2008, 2008, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grácio, C.M.C. Acoplamento bibliográfico e análise de cocitação: Revisão teórico-conceitual. Encontros Bibli 2016, 21, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.; Tata, J. Publication patterns concerning the role of teams/groups in the information systems literature from 1990 to 1999. Inf. Manag. 2005, 42, 1137–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treinta, F.T.; Filho, J.R.F.; Sant’Anna, A.P.; Rabelo, L.M. Metodologia de pesquisa bibliográfica com a utilização de método multicritério de apoio à decisão. Production 2014, 24, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seuring, S.; Mu, M. From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmür, M. Co-citation analysis and the search for invisible colleges: A methodological evaluation. Scientometrics 2003, 57, 27–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.K.; Song, M.; Ding, Y. Content-based author co-citation analysis. J. Informetr. 2014, 8, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, H. Co-citation in the scientific literature: A new measure of the relationship between two documents. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1973, 24, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waltman, L.; van Eck, N.J.; Noyons, E.C.M. A unified approach to mapping and clustering of bibliometric networks. J. Informetr. 2010, 4, 629–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Becker, S.; Bryman, A.; Ferguson, H. Understanding Research for Social Policy and Social Work: Themes, Methods and Approaches; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, B.; Scapens, R.W.; Theobold, M. Research Method and Methodology in Finance and Accounting, 2nd ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R. Case Study Research: Design and Methods—Applied Social Research Methods Series, 4th ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rehn, C.; Kronman, U. Bibliometric Handbook for Karolinska Institutet; Karolinska Institutet: Huddinge, Sweden, 2008; pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, S. A natural resource based view of the firm. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.V.; Fouts, P.A. A Resource-Based Perspective On Corporate Environmental Performance And Profitability. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 534–559. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Sharma, S. Managerial Interpretations and Organizational Context as Predictors of Corporate Choice of Environmental Strategy. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 681–697. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, P. Why Companies Go Green: A Model Of Ecological Responsiveness University of Western Ontario. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 717–736. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M. Green and Competitive: Ending the Stalemate. Haward Bus. Rev. 1995, 73, 120–124. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, E.; Kramer, M.R.; Porter, E.; Kramer, M.R. Estrategia y sociedad Estrategia y sociedad. Haward Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 42–56. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Garriga, E. Corporate Social Responsibility Theories: Mapping the Territory. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 53, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R.; Rogers, D.S. A framework of sustainable supply chain management: Moving toward new theory. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2008, 38, 360–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachon, S.; Klassen, R.D. Extending green practices across the supply chain integration. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2006, 26, 795–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Companies; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Stead, J.G.; Stead, E. Eco-Enterprise Strategy: Standing for Sustainabilit. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 24, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyllick, T.; Hockerts, K. Beyond the Business Case for Corporate Sustainability. Bus. Strateg. Environ. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2002, 11, 130–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiron, D.; Kruschwitz, N.; Haanaes, K. Sustainability Nears a Tipping Point. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2012, 53, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating shared value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava, P.; Scott, H.I. Corporate self-greenewal: Strategic responses to environmentalism. Bus. Strategy Environ. 1992, 1, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Throop, G.M.; Starik, M.; Rands, G.P. Rands Sustainable strategy in a greening world: Integrating the natural environment into strategic management. Adv. Strateg. Manag. 1993, 9, 63–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan, M.J. The eco-industrial revolution: Reveille or requiem for international business. Bus. Contemp. World 1992, 4, 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava, P. Ecocentric management for a risk society. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 118–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P. The role of corporations in achieving ecological sustainability. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 936–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. Are companies planning their organisational changes for corporate sustainability? An analysis of three case studies on resistance to change and their strategies to overcome it. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2013, 20, 275–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.Z.; Bai, Y. Sustainable Development and Long-Term Strategic Management Embedding a Long-Term Strategic Management System into Medium and Long-Term Planning. World Future Soc. 2011, 3, 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R. ISO 26000 and the standardization of strategic management processes for sustainability and corporate social responsibility. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2013, 22, 442–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galbreath, J. Corporate social responsibility strategy: Strategic options, global considerations. Corp. Gov. 2006, 6, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windolph, S.E.; Harms, D.; Schaltegger, S. Motivations for corporate sustainability management: Contrasting survey results and implementation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Kumar, V. Sustainability as corporate culture of a brand for superior performance. J. World Bus. 2013, 48, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Radomska, J. The Role of Managers in Effective Strategy Implementation. Int. J. Contemp. Manag. 2014, 13, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Njiru, G.M. Implementation of Strategic Management Practices in The Water and Sanitation Companies in Kenya. Strateg. J. Bus. Chang. Manag. 2014, 2, 841–856. [Google Scholar]

- Price, A.D.F.; Newson, E. Strategic Management: Consideration of Paradoxes, Processes, and Associated Concepts as Applied to Construction. J. Manag. Eng. 2003, 19, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzberg, H.; Ahlstrand, B.; Lampel, J. Strategy Safari: A Guided Tour Through the Wilds of Strategic Management; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. America’s green strategy. Sci. Am. 1991, 264, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharplin, A. Strategic Management; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Teh, B.; Corbitt, D.E. Building sustainability strategy in business. J. Bus. Strategy 2015, 36, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crittenden, V.L.; Crittenden, W.F. Building a capable organization: The eight levers of strategy implementation. Bus. Horiz. 2008, 51, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beer, M.; Eisenstat, R.A. The Silent Killers of Strategy Implementation and Learning. Sloan Manag. Rev. 2000, 41, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Saltaji, I.M. Corporate Governance Relationship With Strategic Management. Intern. Audit. Risk Manag. 2013, 8, 293–300. [Google Scholar]

- Saltaji, M.F. Corporate governance relation with corporate sustainability. Intern. Audit. Risk Manag. 2013, 8, 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- John, S. Implementing Sustainability Strategy: A Community Based Change Approach. Int. J. Bus. Insights Transform. 2012, 4, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, I. Strategic planning isn’t dead—It changed. Long Range Plann. 1994, 27, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dass, P.; Parker, B. Strategies for managing human resource diversity. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1999, 13, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, F. A framework to implement strategies in organisations. Manag. Decis. 2003, 41, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccò, R.; Guerci, M. Diversity challenge: An integrated process to bridge the ‘implementation gap’. Bus. Horiz. 2014, 57, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Chanda, A.; D’Netto, B.; Monga, M. Managing diversity through human resource management: An international perspective and conceptual framework. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2009, 20, 235–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vele, C.L. Evaluating the strategy implementation process. Manag. Chall. Contemp. Soc. 2012, 4, 192–195. [Google Scholar]

- Håkonsson, D.D.; Burton, R.M.; Obel, B.; Lauridsen, J.T. Strategy Implementation Requires the Right Executive Style: Evidence from Danish SMEs. Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 182–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.; Hickson, D.; Wilson, D. From Strategy to Action. Involvement and Influence in Top Level Decisions. Long Range Plan. 2008, 41, 606–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, W.R.; Cray, D. The Role of Context in the Transformation of Planned Strategy into Implemented Strategy. J. Bus. Manag. Econ. Res. 2013, 4, 721–737. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, S.; Borg, S. Strategy gone bad: Doing the wrong thing. Handb. Bus. Strateg. 2004, 5, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrebiniak, L.G. Obstacles to effective strategy implementation. Organ. Dyn. 2006, 35, 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.; Wilson, D.; Hickson, D. Beyond planning: Strategies for successfully implementing strategic decisions. Long Range Plan. 2004, 37, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan-Berry, K.S.; Somerville, K.A. Linking Change Drivers and the Organizational Change Process: A Review and Synthesis. J. Chang. Manag. 2010, 10, 175–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, O.C., Jr.; Ruekert, R.W. Marketing’s Role in the Implementation of Business Strategies: A Critical Review and Conceptual Framework. J. Mark. 1987, 51, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirthan, J.; Lavanya, L.P.; Nithya, V.E. Strategic Management: Formulation and Implementation. Imp. J. Interdiscip. Res. 2016, 2, 835–836. [Google Scholar]

- Daft, R.L.; Macintosh, N.B. The Nature and Use of Formal Control Systems for Management Control and Strategy10 Implementation. J. Manag. 1984, 10, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Peljhan, D. The Role of Management Control Systems in Strategy Implementation: The Case of a Slovenian Company. Econ. Bus. Rev. 2007, 9, 257–280. [Google Scholar]

- Zeps, A.; Ribickis, L. Strategy Development and Implementation—Process and Factors Influencing the Result: Case Study of Latvian Organisations. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 213, 931–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dess, G.G.; Priem, R.L. Consensus-Performance Research: Theoretical and Empirical Extensions. J. Manag. Stud. 1995, 32, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.D. Maybe I will, maybe I won’t: What the connected perspectives of motivation theory and organisational commitment may contribute to our understanding of strategy implementation. J. Strateg. Mark. 2009, 17, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, F.R. Concepts of Strategic Management, 6th ed.; Prentice Hall: New Jersey, NJ, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, D.W.; Grigsby, M.J. Strategic Management: Formulation and Implementation; Van Nostrand Reinhold: Boston, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Radomska, J. Formalization in strategy implementation—The key to sucess or an unnecessary limitation? Int. J. Contemp. Manag. 2013, 12, 80–92. [Google Scholar]

- Certo, J.P.; Peter, S.C. Strategic Management Concepts and Applications; McGraw Hill, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Mintzberg, H.; Waters, J.A. Of Strategies, Deliberate and Emergent. Strateg. Manag. J. 1985, 6, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Grassl, W.; Pahl, J. Meta-SWOT: Introducing a new strategic planning tool. J. Bus. Strategy 2012, 33, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardi, P.M. Materializing Strategy: The Blurry Line between Strategy Formulation and Strategy Implementation. Br. J. Manag. 2015, 26, S17–S21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.M. The Eight ‘S’s of successful strategy execution. J. Chang. Manag. 2005, 5, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desroches, D.; Hatch, T.; Lawson, R. Are 90% of organisations still failing to execute on strategy? J. Corp. Account. Financ. 2014, 25, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapert, M.I.; Velliquette, A.; Garretson, J.A. The strategic implementation process: Evoking strategic consensus through communication. J. Bus. Res. 2002, 55, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonoma, V.L.; Crittenden, V.T. “Managing marketing implementation. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 1988, 29, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, A.J.I., Jr.; Gamble, A.A.; Strickland, E.E. Strategy Winning in the Market Place, 2th ed.; McGraw-Hill: Brazil, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Enter the triple bottom line. In The Triple Bottom Line: Does It All Add Up; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2004; Chapter 1; Volume 11, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Klettner, A.; Clarke, T.; Boersma, M. The Governance of Corporate Sustainability: Empirical Insights into the Development, Leadership and Implementation of Responsible Business Strategy. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 122, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conference Board. 1999. Available online: https://www.conference-board.org/topics/publicationdetail.cfm (accessed on 22 June 2018).

- Baumgartner, R.J. Organizational culture and leadership: Preconditions for the development of sustainable corporation. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 17, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, M.J.; Buhovac, A.R.; Yuthas, K. Implementing sustainability: The role of leadership and organizational culture. Strateg. Financ. 2010, 91, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Etzion, D. Research on Organisations and the Natural Environment, 1992-Present: A Review. J. Manag. 2007, 33, 637–664. [Google Scholar]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. LLIT 65 What We Know and Don’t Know About Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar]

- Dentchev, N.A. Corporate social performance as a business strategy. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 55, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lankoski, L. Corporate responsibility activities and economic performance: A theory of why and how they are connected. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2008, 17, 536–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1979, 57, 137–145. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. Compet. Strateg. 1980, 1, 396. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 26OOO SOCIAL RESPONSABILITY. 2010. Available online: www.iso.org/iso/home/standards/iso26000 (accessed on 23 June 2018).

- Baumgartner, R.J. Modell, Strategien und Management Instrumente; Rainer Hampp Verlag: Munique, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, T.; Pinkse, J.; Preuss, L.; Figge, F. Tensions in Corporate Sustainability: Towards an Integrative Framework. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 127, 297–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickell, E.B.; Roberts, R.W. The public interest imperative in corporate sustainability reporting research. Account. Public Interest 2014, 14, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klovienė, L.; Speziale, M.T. Sustainability Reporting as a Challenge for Performance Measurement: Literature Review. Econ. Bus. 2015, 26, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballou, B.; Casey, R.J.; Grenier, J.H.; Heitger, D.L. Exploring the strategic integration of sustainability initiatives: Opportunities for accounting research. Account. Horiz. 2012, 26, 265–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.; Lülfs, R. Legitimizing Negative Aspects in GRI-Oriented Sustainability Reporting: A Qualitative Analysis of Corporate Disclosure Strategies. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 123, 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampikoski, T.; Möller, K.; Westerlund, M.; Rajala, R.; Möller, K. Green Innovation Games: Value-creation strategies for corporate sustainability. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2014, 57, 88–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehhi, A.; Nobanee, H.; Khare, N. The impact of sustainability practices on corporate financial performance: Literature trends and future research potential. Sustainability 2018, 10, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-González, M.D.; Rubio-Andrés, M.; Sastre-Castillo, M.Á. Building corporate reputation through sustainable entrepreneurship: The mediating effect of ethical behavior. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldavska, A. Defining organizational context for Corporate Sustainability Assessment: Cross-disciplinary approach. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, F.; Veltri, S.; Venturelli, A. Sustainability strategy and management control systems in family firms. Evidence from a case study. Sustainability 2017, 9, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garstecki, D.; Kowalczyk, M.; Kwiecinska, K. CSR practices in Polish and Spanish stock listed companies: A comparative analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1054. [Google Scholar]

| Items and Search Criteria | |

|---|---|

| Items | Criteria |

| Period: | No chronological filter |

| Online databases: | Web of Science (WOS) |

| Key-words: | (Implementation of the sustainability strategy in companies) |

| Systematization by search category: | Management or Business |

| Systematization by document type: | Articles and Review |

| Software used: | Endnote X8 and Microsoft Excel 2016 |

| Language | English |

| Documents identified and analyzed: | 97 |

| Source Title | No. of Publications | Impact Factor (SJR) | Quartile | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Journal of Business Ethics | 8 | 1.276 | Quartile1 | Netherlands |

| Business Strategy and the Environment | 7 | 1.881 | Quartile 1 | USA |

| Amfiteatru Economic | 5 | 0.180 | Quartile3 | Romania |

| Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management | 5 | 1.706 | Quartile 1 | USA |

| Benchmarking an International Journal | 4 | 0.314 | Quartile3 | UK |

| Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management | 4 | 0.867 | Quartile 1 | UK |

| Quality Access to Success | 3 | 0.229 | Quartile3 | Romania |

| Total Quality Management Business Excellence | 3 | 0.634 | Quartile 1 | UK |

| California Management Review | 2 | 2.209 | Quartile 1 | USA |

| Corporate Governance the International Journal of Business in Society | 2 | 1.500 1 | Quartile1 | UK |

| Others <2 | 43 | Source: Adapted from WOS and SJR Impact Factor | ||

| Total | 97 | |||

| Author/Article/Journal | Total Citations |

|---|---|

| Christmann, P. (2000). Effects of “best practices” of environmental management on cost advantage: The role of complementary assets. Academy of Management Journal, 43(4), 663–680. | 834 |

| Golicic, S. L., and Smith, C. D. (2013). A meta-analysis of environmentally sustainable supply chain management practices and firm performance. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 49(2), 78–95. | 167 |

| Fernández, E., Junquera, B., and Ordiz, M. (2003). Organizational culture and human resources in the environmental issue: a review of the literature. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 14(4), 634–656. | 103 |

| Mueller, M., Dos Santos, V. G., and Seuring, S. (2009). The contribution of environmental and social standards towards ensuring legitimacy in supply chain governance. Journal of Business Ethics, 89(4), 509–523. | 99 |

| Baumgartner, R. J. (2014). Managing corporate sustainability and CSR: A conceptual framework combining values, strategies and instruments contributing to sustainable development. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 21(5), 258–271. | 85 |

| Perez-Aleman, P., and Sandilands, M. (2008). Building value at the top and the bottom of the global supply chain: MNC-NGO partnerships. California Management Review, 51(1), 24–49. | 82 |

| Hsieh, Y. C. (2012). Hotel companies’ environmental policies and practices: a content analysis of their web pages. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 24(1), 97–121. | 63 |

| Maslennikova, I., and Foley, D. (2000). Xerox’s approach to sustainability. Interfaces, 30(3), 226–233. | 57 |

| Olsen, M., and Boxenbaum, E. (2009). Bottom-of-the-pyramid: Organizational barriers to implementation. California Management Review, 51(4), 100–125. | 56 |

| Duarte, F. (2010). Working with corporate social responsibility in Brazilian companies: The role of managers’ values in the maintenance of CSR cultures. Journal of Business Ethics, 96(3), 355–368. | 53 |

| Author(s)/Year | Co-Citations | Type of Document | Content Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster 1—Environmental Questions and Sustainable Competitive Advantage and Inherent Theoretical Support | |||

| Hart (1995) [44] | 13 | Theoretical |

|

| Russo and Fouts (1997) [45] | 12 | Empirical/qualitative |

|

| Sharma (2000) [46] | 9 | Empirical/quantitative |

|

| Barney (1991) [16] | 8 | Empirical/qualitative |

|

| Bansal (2000) [47] | 7 | Empirical/qualitative |

|

| Porter (1995) [48] | 7 | Empirical/qualitative |

|

| Cluster 2—Corporate Social Responsibility and Competitive Advantage | |||

| Porter and Kramer (2006) [49] | 10 | Empirical/qualitative |

|

| Freeman (1984) [50] | 8 | Book |

|

| Bansal (2005) [13] | 7 | Empirical/quantitative |

|

| Garriga (2004) [51] | 7 | Theoretical |

|

| Cluster 3—Sustainable Management of the Supply Chain | |||

| Seuring and Müller (2008) [33] | 13 | Theoretical |

|

| Carter and Rogers (2008) [52] | 9 | Theoretical |

|

| Vachon and Klassen (2006) [53] | 8 | Empirical/quantitative |

|

| Authors | Factors |

|---|---|

| Carcano [5], Hahn [67] | Organizational commitment |

| Windolph, Harms and Schaltegger [68] | Motivations of capital holders |

| Gupta and Kumar [69], Radomska [70] | Type of organisational culture |

| Radomska [70] | Type of leadership and the motivation of all |

| Authors | Factors |

|---|---|

| Okumus [84], Riccò and Guerci; Shen, Chanda, D’Netto and Monga; Vele [85,86,87] | Degree of resistance to change in the whole organisational structure |

| Håkonsson, Burton, Obel and Lauridsen [88]; Jin and Bai [65]; Miller, Hickson and Wilson; Rose and Cray [89,90] | Managers’ individual competences and capacities |

| Finkelstein and Borg [91]; Hrebiniak [92]; Miller, Wilson and Hickson; Radomska; Sharplin; Whelan-Berry and Somerville [93,94] | Type of leadership (management style) |

| Walker Jr and Ruekert [95] | Organisational processes |

| Amirthan, Lavanya and Nithya [96]; Daft and Macintosh [97] | Control systems |

| Amirthan, Lavanya and Nithya [96]; Peljhan [98]; Zeps and Ribickis [99] | Reward and incentive systems |

| Amirthan, Lavanya and Nithya [96]; Dess and Priem [100]; Smith [101] | Managers’ degree of organisational commitment |

| Amirthan, Lavanya and Nithya [96]; Whelan-Berry and Somerville [94] | Changes to the mission and vision |

| State-of-the-Art | Dimensions | Contributions |

|---|---|---|

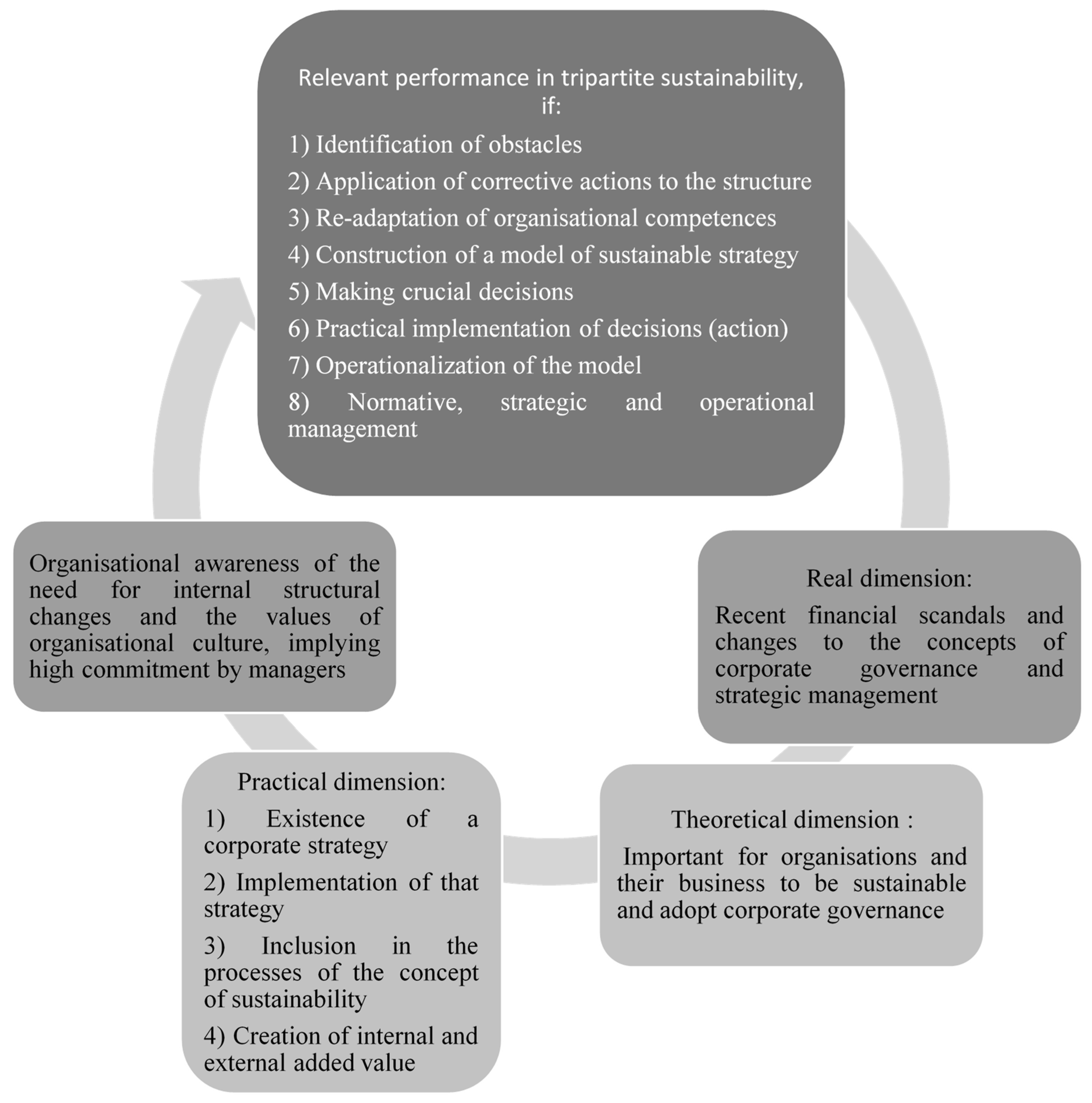

| Corporate sustainability and its integration in global strategy | Real Saltaji [79,80] | Review of the premises of corporate governance as the consequence of the effects of recent financial scandals, which originated the need for more creative and dynamic models of strategic management, to allow integrating corporate sustainability in the global strategy. |

| Formulation and implementation of sustainable strategy | Theoretical Hrebiniak (2006) [92] Klettner et al. [117] Saltaji [82] | Organisations and their business should be more sustainable and corporate governance practices should be adopted, to ensure:

|

| Corporate sustainability versus formulation and implementation of sustainable strategy | Alteration Crittenden and Crittenden [77] | Having organisational awareness of the need for internal structural changes and the values of organisational culture, implying great commitment by managers. |

| Formulation and implementation of sustainable strategy | Practical Beer and Eisenstat [78] Bonoma and Crittenden [112] Crittenden and Crittenden [77] David [102] Thompson Jr et al. [113] Baumgartner [22], [117], [126] Hahn [66] Hahn et al. (2014) [127] Saltaji [79], [80] Stead and Stead (2000) [55] |

As a whole, these steps allow the construction of a model of sustainable strategy, to fill the gap between the various phases of the strategy, whose results are the acquisition of internal and external legitimacy, the formulation of a robust, sustainable strategy and the implementation and efficient assessment of the strategy formulated, with relevant performance in tripartite (economic, social and environmental) sustainability. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodrigues, M.; Franco, M. The Corporate Sustainability Strategy in Organisations: A Systematic Review and Future Directions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6214. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226214

Rodrigues M, Franco M. The Corporate Sustainability Strategy in Organisations: A Systematic Review and Future Directions. Sustainability. 2019; 11(22):6214. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226214

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodrigues, Margarida, and Mário Franco. 2019. "The Corporate Sustainability Strategy in Organisations: A Systematic Review and Future Directions" Sustainability 11, no. 22: 6214. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226214

APA StyleRodrigues, M., & Franco, M. (2019). The Corporate Sustainability Strategy in Organisations: A Systematic Review and Future Directions. Sustainability, 11(22), 6214. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11226214