What Drives Sustainable Brand Awareness: Exploring the Cognitive Symmetry between Brand Strategy and Consumer Brand Knowledge

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. Brand Associative Network and Brand Awareness

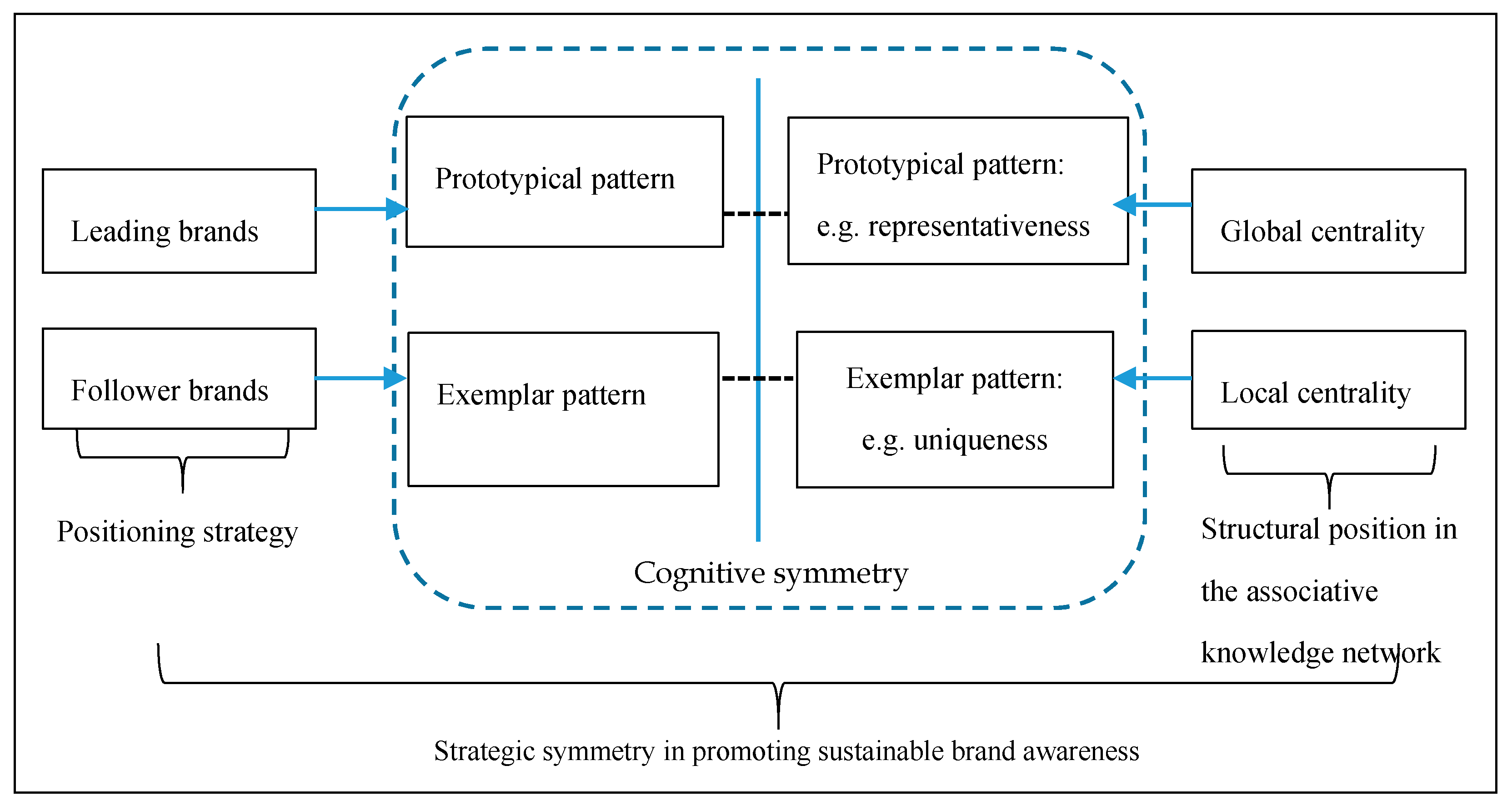

2.2. Consumers’ Associative Knowledge, Brand Strategy, and Sustainable Brand Performance (Awareness)

2.3. Brand Structural Position in Association Network and Brand Awareness

2.4. Consumers’ Psychological Cognitive Patterns and Brand Awareness

2.5. Symmetry between the Brand Strategy and Brand Structural Position in the Brand Associative Knowledge Network

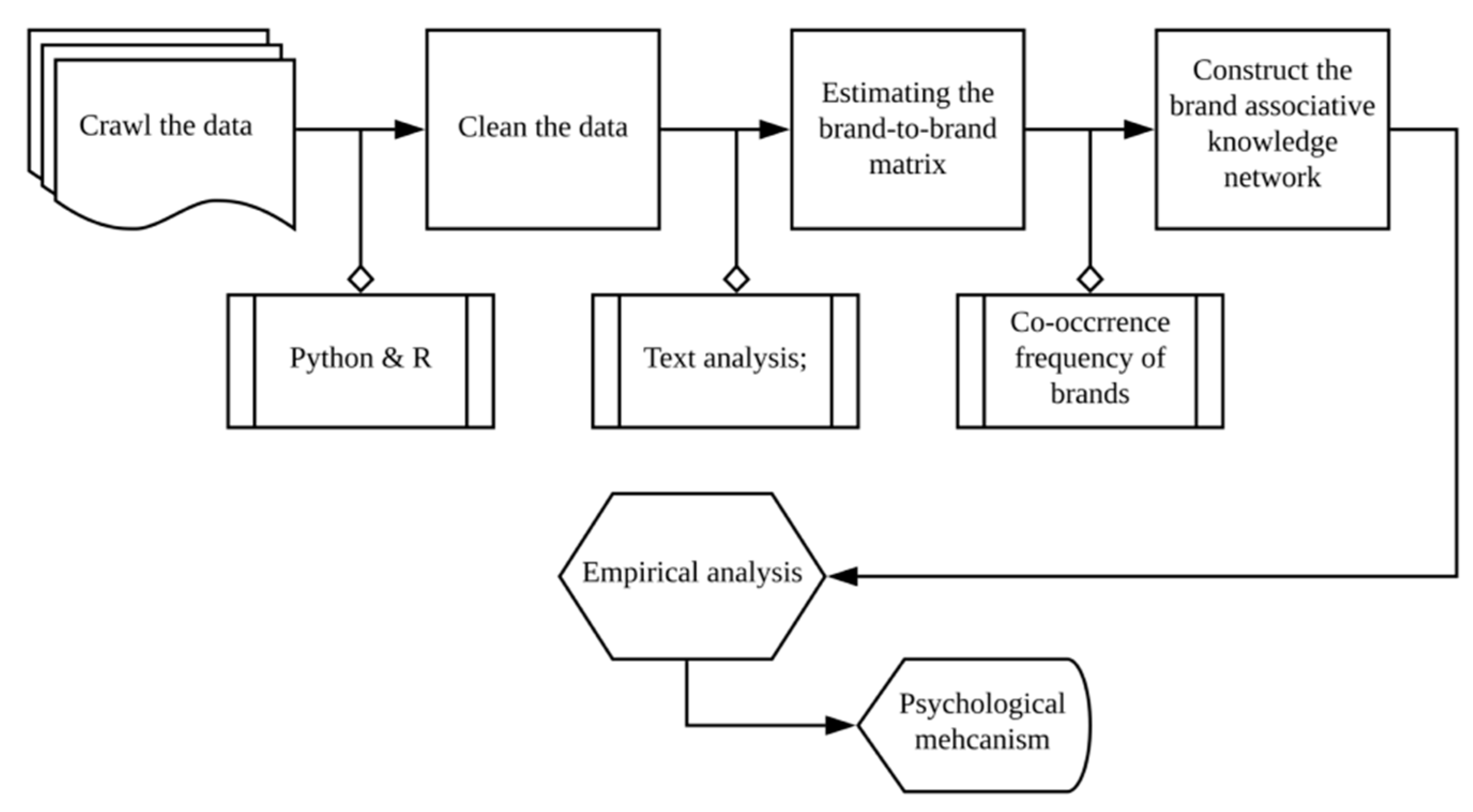

3. Methodology

3.1. Data

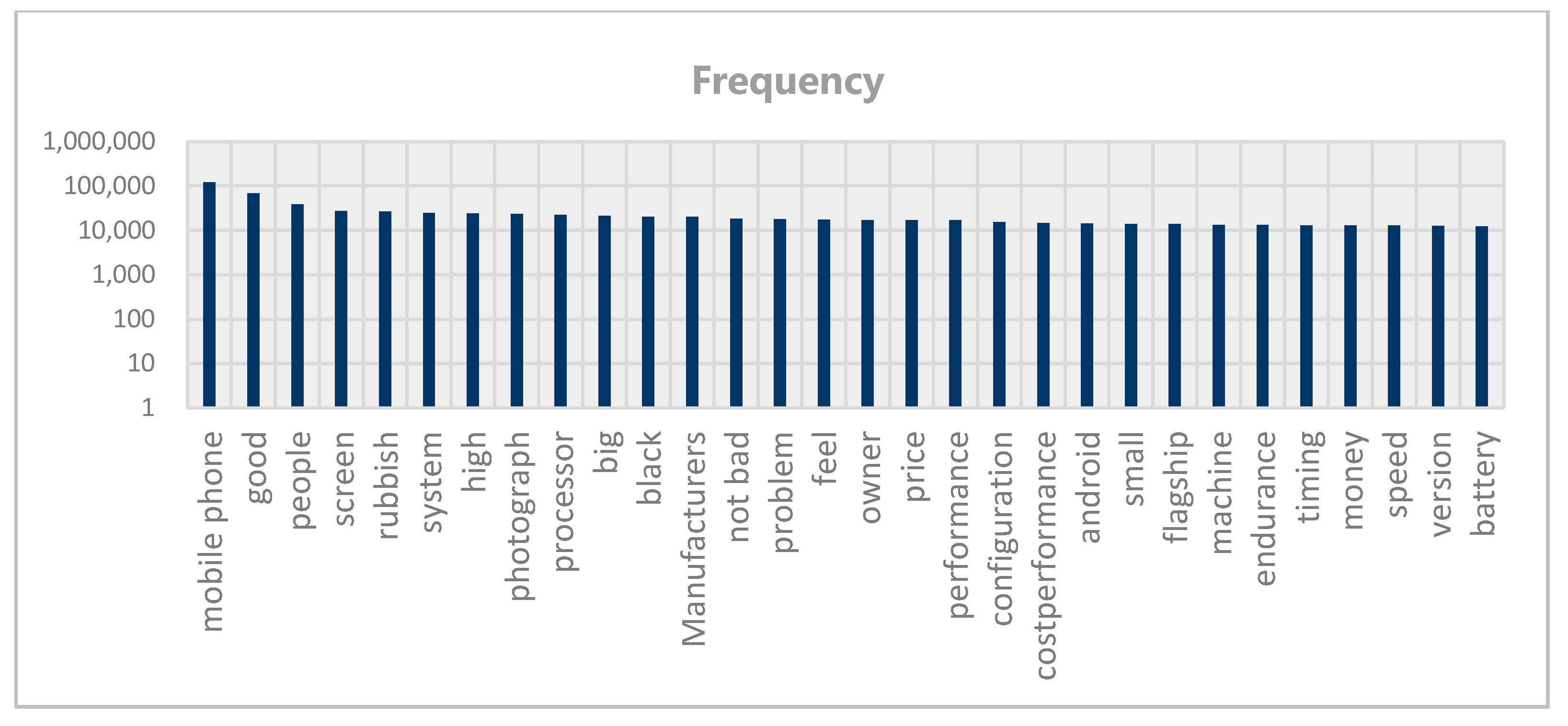

3.2. Constructing the Brand Associative Knowledge Network

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Experiment 1: Main Effect and Symmetrical Matching Effect

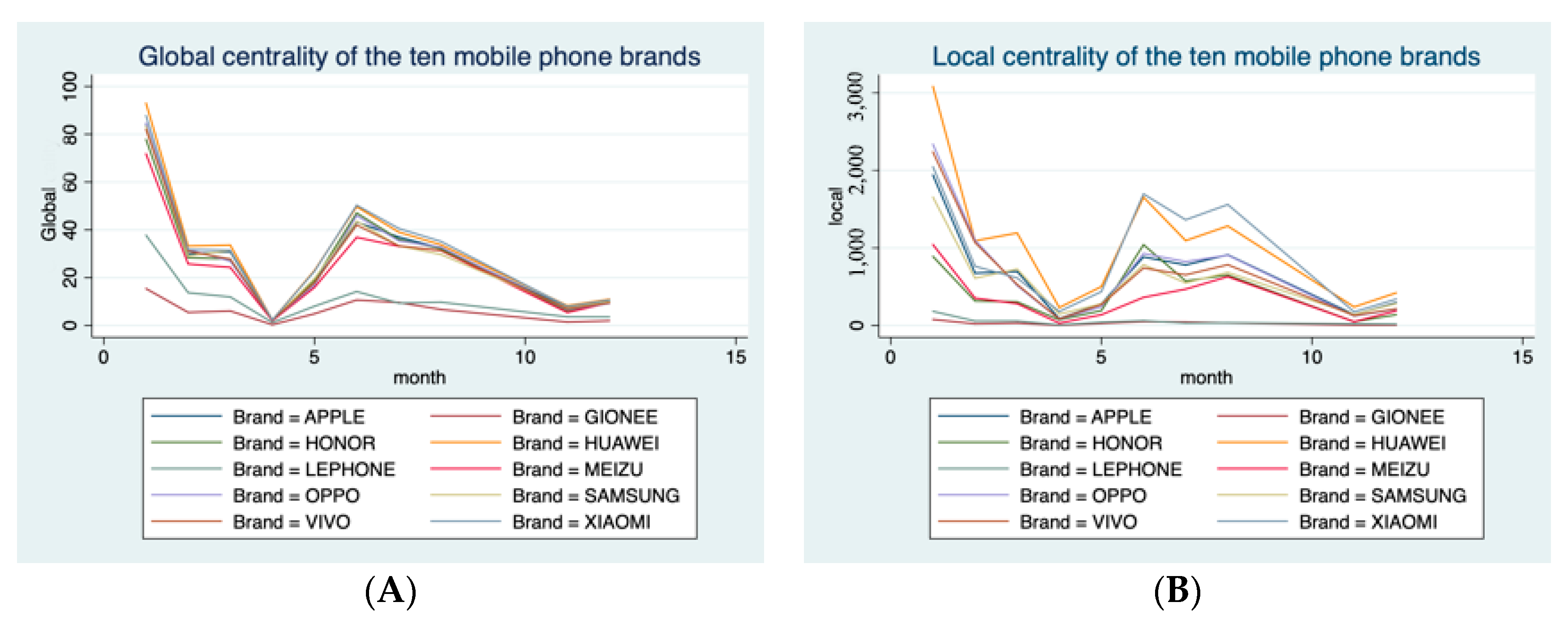

4.1.1. Variables

4.1.2. Analysis

4.1.3. Results

4.1.4. Robustness Check

4.2. Study 2: Consumers’ Psychological Cognitive Mechanism Regarding Leading and Follower Brands

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hunt, S.D. The Strategic Imperative and Sustainable Competitive Advantage: Public Policy Implications of Resource-Advantage Theory. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1999, 27, 144–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.; Wright, M.; Ketchen, D.J. The resource-based view of the firm: Ten years after 1991. J. Manag. 2001, 27, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, G.; Yunchan, Z.; Rizwan, A.; Ruijin, G. Capturing Associations and Sustainable Competitiveness of Brands from Social Tags. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1592. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, M.T. Knowledge Networks: Explaining Effective Knowledge Sharing in Multiunit Companies. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 232–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culotta, A.; Cutler, J. Mining Brand Perceptions from Twitter Social Network. Mark. Sci. 2016, 35, 343–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, D.R.; Loken, B.; Kim, K.; Monga, A.B. Brand Concept Maps: A Methodology for Identifying Brand Association Networks. J. Mark. Res. 2006, 43, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaltman, G.; Coulter, R.H. Seeing the Voice of the Customer: Metaphor-Based Advertising Research. J. Advert. Res. 1995, 35, 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Saura, J.R.; Reyes-Menendez, A.; Bennett, D.R. How to Extract Meaningful Insights from UGC: A Knowledge-Based Method Applied to Education. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Managing Customer-Based Brand Equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.R. The Architecture of Cognition; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, G.R.; Iacobuycci, D.; Calder, B.J. Brand diagnostics: Mapping branding effects using consumer associative networks. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1998, 111, 306–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichert, T.; Heyer, G.; Schontag, K. Co-Word Analysis for Assessing Consumer Associations: A Case Study in Market Research. In Affective Computing and Sentiment Analysis; Text, Speech and Language Technology; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 45. [Google Scholar]

- Attneave, F. Symmetry, Information, and Memory for Patterns. Am. J. Psychol. 1955, 68, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horowitz, L.M.; Gordon, A.M. Associative symmetry and second-language learning. J. Educ. Psychol. 1972, 63, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelson, M.J.; Lee, S.P. The effects of symmetry and contour on recognition memory in children. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 1982, 32, 373–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, D.A. Measuring Brand Equity Across Products and Markets. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1996, 38, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.C. Managing Brand Equity: Capitalizing on the Value of a Brand Name, by David A. Aake. J. Brand Manag. 1993, 1, 69–71. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, A.M.; Loftus, E.F. A Spreading Activation Theory of Semantic Processing. Psychol. Rev. 1975, 82, 407–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raaijmakers, J.G.W.; Shiffrin, R.M. Search of Associative Memory. Psychol. Rev. 1981, 88, 93–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyer, R.S.; Srull, T.K. Person Memory and Judgment. Psychol. Rev. 1989, 96, 58–83. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.R.; Bower, G.H. Human Associative Memory; Winston and Sons: Washington, DC, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. Assessment of Destination Brand Associations: An Application of Associative Network Theory and Network Analysis Methods. Ph.D. Dissertation, East Eisenhower Parkway, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, H.; Kannan, P.K. The Informational Value of Social Tagging Networks. J. Mark. 2014, 78, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nam, H.; Joshi, Y.V.; Kannan, P.K. Harvesting Brand Information from Social Tags. J. Mark. 2017, 81, 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Strategic Brand Management: Building, Measuring, and Managingbrand Equity, 3rd ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle Rivder, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S.; Berry, S. Brand salience versus brand image: Two theories ofadvertising effectiveness. J. Advert. Res. 1998, 38, 77–82. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell, T.B.; Roy, D.P. Exploring managers’ perceptions ofthe impact of sponsorship on brand equity. J. Advert. 2001, 30, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avram, A.; Benvenuto, M.; Avram, C.; Gravili, G. Assuring SME’s Sustainable Competitiveness in the Digital Era: A Labor Policy between Guaranteed Minimum Wage and ICT Skill Mismatch. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Newman, M.E.J. Spread of epidemic disease on networks. Phys. Rev. E 2002, 66, 016128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Newman, M. Analysis of weighted networks. Phys. Rev. E 2004, 70, 056131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aral, S.; Walker, D. Creating Social Contagion Through Viral Product Design: A Randomized Trial of Peer Influence in Networks. Manag. Sci. 2011, 57, 1623–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bapna, R.; Umyarov, A. Do Your Online Friends Make You Pay? A Randomized Field Experiment on Peer Influence in Online Social Networks. Manag. Sci. 2015, 61, 1902–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freeman, L.C. Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Soc. Netw. 1978, 1, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wasserman, S.; Faust, K. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Ransbotham, S.; Kane, G.C.; Lurie, N.H. Network Characteristics and the Value of Collaborative User-Generated Content. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2011, 31, 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goldenberg, J.; Han, S.; Lehmann, D.R.; Hong, J.W. The Role of Hubs in the Adoption Process. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietro Battiston, L.S. Boundedly rational opinion dynamics in social networks: Does indegree matter? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2015, 119, 400–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iyengar, R.; Van den Bulte, C.; Valente, T.W. Opinion Leadership and Social Contagino in New Product Diffusion. Mark. Sci. 2010, 30, 224–229. [Google Scholar]

- Sabidussi, G. The centrality of a graph. Psychometrika 1966, 31, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.K. Brand extensions in a competitive context: Effects of competitive targets and product attribute typicality of perceived quality. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 1998, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sujan, M. Consumer knowledge: Effects on evaluation strategies mediating consumer judgments. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alba, J.W.; Hutchiinson, W. Dimensions of Consumer Expertise. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 13, 411–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.D. Consumer Choice Strategies forComparing Noncomparable Alternatives. J. Consum. Res. 1984, 11, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, E.J.; Johnson, E.J. What Do Con-sumers Know About Familiar Products? Adv. Consum. Res. 1980, 7, 417–423. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, S.; Houston, M.J. Exemplars or Beliefs? The Impact of Self-View on the Nature and Relative Influence of Brand Associations. J. Consum. Res. 2006, 32, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Livio, M. The Equation That Couldn’t Be Solved: How Mathematical Genius Discovered the Language of Symmetry; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Einstein, A. Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper. Ann. Phys. 1905, 322, 891–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwichtenberg, J. Physics from Symmetry; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, R.; Ramachandran, R.V. Symmetry and Economic Invariance; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, D.W.; Orr, P.T.; Lazar, S.M.; Breton, D.; Gerard, J. Human Preferences for Symmetry: Subjective Experience, Cognitive Conflict and Cortical Brain Activity. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Enquist, M.; Arak, A. Symmetry, Beauty and Evolution. Nature 1994, 372, 169–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernstein, S. From share leader to true brand leader. Strateg. Dir. 2008, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, B.; Alpert, F. The relative influence of pioneer and follower price on reference price and value perceptions. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2010, 19, 504–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintal, V.; Phau, I. Do Prototypical Brands Have an Advantage Over Me-Too Brands in the Mature Marketplace? J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2013, 25, 305–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintal, V.; Phau, I. Brand leaders and me-too alternatives: How do consumers choose? Mark. Intell. Plan. 2013, 31, 367–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, I.; Stephen, A.; Bart, Y. Spillover effects in seeded word-of-mouth marketing campaigns. Mark. Sci. 2016, 36, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagle, N.; Pentland, A.; Lazer, D. Inferring friendship network structureby using mobile phone data. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 15274–15278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Terhi-Anna, W. Mobile Phone Use as Part of Young People’s Consumption Styles. J. Consum. Policy 2003, 26, 441–463. [Google Scholar]

- Ippoliti, N.B.; L’Engle, K.; Ippoliti, N.B.; L’Engle, K. Meet Us on the Phone: Mobile Phone Programs for Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health in Low-To-Middle Income Countries. Reprod. Health 2017, 14, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dijkstra, E.W. A note on two problems in connection with graphs. Numer. Math. 1959, 1, 269–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blundell, R.; Bond, S. Initial Conditions and Moment Restrictions in Dynamic Panel Data Models. J. Econ. 1998, 87, 115–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Petrin, A.; Train, K. A Control Function Approach to Endogeneity in Consumer Choice Models. J. Mark. Res. 2010, 47, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rabe-Hesketh, S.; Skrondal, A.; Pickles, A. Maximum Likelihood Estimation of Limited and Discrete Dependent Variable Models with Nested Random Effects. J. Econ. 2005, 128, 301–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Authors | Data Resources | Methodology | Brand Performance | Symmetric Brand Strategy | Psychological Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zaltaman and Coulter, 1995 | Interview data (cross-section data) | - | × | × | × |

| Henderson, Acobucci, and Calder, 1998 | Survey data (cross-section data) | Network analysis | × | × | × |

| John et al., 2006 | Interview or survey data (cross-section data) | - | × | × | × |

| Teichert and Schöntag, 2010 | Survey data (cross-section data) | Factor analysis; network analysis | × | × | × |

| Nam and Kannan, 2014 | User-generated data (panel data) | Word frequency analysis; text analysis; empirical analysis | √ | × | × |

| Nam, Joshi, and Kannan, 2017 | User-generated data (panel data) | Word frequency analysis | × | × | × |

| Gong et al., 2019 | User-generated data (cross-section data) | Word frequency analysis; network analysis | × | × | × |

| The current work | User-generated data (panel data) | Word frequency analysis; text analysis; network analysis; empirical analysis | √ | √ | √ |

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand awareness | 1 | |||||||

| Local centrality | 0.3534 * | 1 | ||||||

| Global centrality | 0.2552 | 0.6911 * | 1 | |||||

| Market position | 0.1675 | 0.3017 * | 0.1449 | 1 | ||||

| Brand age | 0.1081 | 0.1056 | 0.085 | −0.113 | 1 | |||

| Total products | −0.199 | 0.0591 | 0.0375 | −0.0422 | 0.8663 * | 1 | ||

| New products | −0.0576 | 0.2656 * | 0.1728 | 0.0368 | 0.3932 * | 0.6413 * | 1 | |

| Brand exposure | 0.2524 | 0.2298 | 0.0916 | 0.0012 | 0.5962 * | 0.5242 * | 0.4906 * | 1 |

| Average | 3.41 × 107 | 5505.19 | 25.271 | 0.3 | 23.06 | 324.23 | 44.89 | 86,336.72 |

| Standard error | 2.45 × 107 | 5994.305 | 21.979 | 0.460 | 22.472 | 464.172 | 19.258 | 133,426.9 |

| Variables | Dependent Variable: Brand Awareness | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypotheses | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Interception | 0.011 (0.571) | 0.006 (0.684) | 0.016 (0.372) | 0.048 *** (0.000) | |

| Main effects: | |||||

| Local centrality | H1 | 0.435 *** (0.000) | 0.756 * (0.064) | 0.245 *** (0.000) | |

| Global centrality | H2 | 0.794 *** (0.000) | 0.329 (0.447) | 0.375 *** (0.000) | |

| (Symmetric matching) Moderate effects: | |||||

| Positioning strategy × Global centrality | H4(a) | 3.219 ** (0.021) | 8.299 * (0.055) | ||

| Positioning strategy × Local centrality | H4(b) | −1.110 ** (0.017) | −4.78 *** (0.001) | ||

| Positioning strategy | −0.021 (0.093) | −0.027 *** (0.003) | |||

| Control variables: | |||||

| Total products | −0.841 *** (0.000) | −0.318 *** (0.000) | −0.311 *** (0.004) | 0.300 (0.323) | |

| New products | 0.723 *** (0.000) | −0.401 ** (0.019) | −0.320 (0.157) | −0.3221 (0.121) | |

| Brand exposure | 0.065 (0.160) | 0.020 (0.553) | 0.019 (0.552) | −0.022 *** (0.000) | |

| Brand age | 0.948 (0.000) | 0.410 *** (0.000) | 0.379 *** (0.001) | 0.072 *** (0.000) | |

| Bias correction: | |||||

| −0.219 *** (0.000) | |||||

| 0.352 *** (0.000) | |||||

| R2 | 0.515 | 0.769 | 0.799 | ||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.495 | 0.755 | 0.779 | ||

| Hypotheses | Method | Coefficient Estimation (Model 4) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Higher local centrality in the brand association network is related to higher brand awareness. | Study 1: Empirical analysis | Local centrality: β = 0.245, p < 0.01 | H1 and H2 are tested by checking the main effect of local centrality and global centrality on the sustainable brand awareness |

| H2: Higher global centrality in the brand association network is related to higher brand awareness. | global centrality: β = 0.375, p < 0.01 | ||

| H4(a): Compared to leading brands, follower brands enhance the positive relationship between local brand centrality and brand awareness. | two-way interaction term of positioning strategy and global centrality: β = 8.299, p = 0.055 | H4 is tested by checking the moderating effect of brand positioning strategy on the two centralities | |

| H4(b): Compared to follower brands, leading brands enhance the positive relationship between local brand centrality and brand awareness. | two-way interaction term of positioning strategy and local centrality: β = −4.78, p < 0.01 | ||

| H3(a): Leading brands are more likely to stimulate cognition in a prototypical pattern; | Study 2: Textual analysis | - | H3 is tested by one-way ANOVA analysis on the consumer cognition pattern of brands with different positioning strategy |

| H3(b): Follower brands are more likely to stimulate cognition in an exemplar pattern. | - |

| Variables | Dependent Variable: Brand Awareness | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |

| Interception | 15.974 (0.00) | 15.973 (0.00) | 14.781 (0.00) |

| Main effects: | |||

| Local centrality | 0.000 *** (0.00) | 0.000 *** (0.00) | |

| Global centrality | 0.008 *** (0.000) | 0.008 *** (0.00) | |

| (Symmetric matching) Moderate effects: | |||

| Positioning strategy × Global centrality | 0.006 *** (0.00) | ||

| Positioning strategy × Local centrality | −0.00 *** (0.00) | ||

| Positioning strategy | 0.690 (0.126) | ||

| Control variables: | |||

| Total products | −0.000 *** (0.03) | −0.003 ** (0.030) | −0.003 *** (0.005) |

| New products | 0.002 (0.118) | 0.026 ** (0.04) | −0.031 ** (0.04) |

| Brand exposure | 0.000 *** (0.00) | 0.00 *** (0.00) | 0.00 *** (0.552) |

| Brand age | 0.043 *** (0.000) | 0.043 *** (0.040) | 0.052 *** (0.001) |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gong, X.; Wang, C.; Yan, Y.; Liu, M.; Ali, R. What Drives Sustainable Brand Awareness: Exploring the Cognitive Symmetry between Brand Strategy and Consumer Brand Knowledge. Symmetry 2020, 12, 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12020198

Gong X, Wang C, Yan Y, Liu M, Ali R. What Drives Sustainable Brand Awareness: Exploring the Cognitive Symmetry between Brand Strategy and Consumer Brand Knowledge. Symmetry. 2020; 12(2):198. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12020198

Chicago/Turabian StyleGong, Xuan, Changzheng Wang, Yi Yan, Maohong Liu, and Rizwan Ali. 2020. "What Drives Sustainable Brand Awareness: Exploring the Cognitive Symmetry between Brand Strategy and Consumer Brand Knowledge" Symmetry 12, no. 2: 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12020198

APA StyleGong, X., Wang, C., Yan, Y., Liu, M., & Ali, R. (2020). What Drives Sustainable Brand Awareness: Exploring the Cognitive Symmetry between Brand Strategy and Consumer Brand Knowledge. Symmetry, 12(2), 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12020198