1. Introduction

Oleotourism has been defined as “a form of domestic tourism (especially in rural areas) related to gastronomy, which allows for the essence of the culture encompassing the world of the olive to be captured while deepening knowledge about everything connected to olive oil” ([

1], p. 180) and it “may be a complementary means of income for the rural population” ([

2], p. 116).

The business of oleotourism is continuously—albeit slowly—growing in Europe and especially in the Mediterranean area, due to the abundance of olive trees in this part of the world. Moreover, other countries, such as Brazil and the US, recently started some initiatives based on olive oil as the main attraction for tourists. Much evidence has shown the recent trend towards this form of tourism, as in 2005, the World Tourism Organization stressed the relevance of natural tourism as a lever for local development [

3] (UNWTO, 2005), also recalling “The Routes of the Olive Tree” [

4], as well as the Financial Times [

5] and the Olive Oil Times [

6] describing oleotourism as “the next big thing” with specific reference to the so-called World Capital of Olive Oil, the city of Jaén, in Andalucía, in the southern part of Spain.

Additionally, scholars have recognized the increasing relevance of this form of tourism; indeed, recent contributions paid attention to its potential, considering it as still unexploited in full, as in analyses in Portugal (Bezerra and Correia, 2019) [

7], Spain (Folgado-Fernández et al., 2019) [

8], and Greece (Karampela et al., 2019) [

9], among others. Scholars agree that oleotourism plays a key role for multiple reasons, due to its relations to local territories, firms, resources, and other forms of tourism. These elements have been considered and combined in various ways by authors dealing with oleotourism and sustainable development from multiple perspectives (Millán et al., 2018) [

2], the support it interchanges with other tourism-based activities (Čehić et al., 2020) [

10], the interplay with food experience and with food as a way to brand a destination (Jiménez-Beltrán et al., 2016 [

11], Moral Cuadra et al., 2020 [

12]), and the effects it may offer to local development for both tourism and other activities occurring in the surrounding areas (Tregua et al., 2018) [

13]. Therefore, the effects of oleotourism and the influences it receives from other activities and factors are multiple, leading to it stimulating research interest, with special reference to local factors (as resources and conditions), interventions to be done (also in terms of sustainability), and empirical research to be performed to gain more knowledge on the topic. Indeed, several questions are still open, as highlighted by scholars recently calling for further research, especially as it concerns the seasonality of this business (Martín-Martín et al., 2020) [

14], the links that have emerged between this special interest tourism and other activities and the chances to further consolidate them (Pulido-Fernández et al., 2019 [

15]; Parrilla-González et al., 2020 [

16]), and the effects on firms diversifying their core business to profit from the growing interest in oleotourism (Parrilla-González et al., 2020) [

16].

Due to these calls for research and the growing attention paid to this topic, this paper aims to offer an in-depth analysis of the elements favoring the development of oleotourism in the Mediterranean area. In more detail, and due to the interplay with the local context, the authors plan to combine and compare the evidence from three Mediterranean countries offering examples of tourism initiatives based on olive oil, namely, Spain, Italy, and Croatia. In particular, we chose to compare these three countries because, according to the Official Index of the World’s Best Olive Oils, they gained the highest number of awards – especially the top-quality award, known as best-in-class–in Europe for olive oil quality in 2017, 2018, and 2019. Furthermore, Spain, Italy, and Croatia are in different stages in oleotourism development: (1) although more efforts are needed, in Spain many initiatives have taken place in the last years; (2) in Italy, oleotourism is growing in the wake of enotourism; (3) Croatia is starting to pay attention to this new form of tourism after the development of forms of gastro-tourism and the increasing number of olive trees.

The similarities and differences emerging from the comparison will expand the understanding of this phenomenon and lead to the highlighting of key features and choices in favoring its development in the coming years. Therefore, this research aims to identify additional knowledge for scholars, managers, and policy-makers, thanks to the combination of a review of the literature and the analysis of concrete examples and data from the local contexts. To that end, the next sections offer a review of the academic contributions on the topic, and then the description of the sources for the analysis, leading to the description of the contexts, the analysis itself, and the discussion of results. Conclusions and suggestions for further research complete the paper.

2. Literature Review

For several years, the attention that scholars paid to agritourism led to the emergence of a wide array of literature on this topic, due to ties to local resources (Croce and Perri, 2017) [

17], the viability of small (and even micro-) firms in agribusiness (Gil Arroyo et al., 2013) [

18], and the local context and its development (Armesto López and Martin, 2005) [

19]. Similar characteristics may be found in the emerging form of agritourism related to olive oil, known as oleotourism or olive oil tourism. Indeed, existing literature describes the effects on the tourism industry and gastronomy (Richards, 2002) [

20], the role of small firms dealing with olive oil production (Millán Vázquez de la Torre et al., 2014 [

21], Folgado-Fernández et al., 2020 [

22]) and the interplay with local areas and the entire olive oil industry (Duarte Alonso and Northcote, 2010 [

23]; Hernández-Mogollón et al., 2019 [

24]).

The concept of territory is usually linked to topics such as natural resources and sustainability issues. In this regard, many scholars’ contributions dealing with territorial development discuss the compatibility of tourism activities and local asset management, focusing on risks with respect to the integrity of the natural resources and the surrounding areas. Other scholars stressed the opportunities that may come from projects aimed at territorial development and local tourism development based on local resources, stating that tourism-oriented activities can even create new benefits for the local area (Loumou and Giourga, 2003 [

25]; Millán et al., 2018 [

2]).

According to this, recently many contributions dealing with the connection between olive oil production and tourism have been published, and, in line with the relevance acquired in the last few decades by sustainability issues, scholars framed oleotourism mainly using sustainable tourism as a context, as well as other topics like agritourism, cultural tourism, or even health tourism (Petroman and Petroman, 2010 [

26]; Ruiz Guerra, 2010 [

27]; Petroman, 2013 [

28]).

In detail, when scanning literature on the theme, oleotourism, olive oil tourism, or oleo tourism emerges as a tourism approach linked to local resources, namely, olive oil production. The literature on the topic is still scarce, with special reference to empirical studies, although publications—both scientific and informative—describing initiatives linking olive oil production and tourism are increasing in number (Millán et al., 2018) [

2].

For example, Pulina and colleagues (2006) [

29] adopted an approach based on the three pillars of sustainability, as suggested by Brundtland (1987) [

30], stating that, to be successful, oleotourism projects must consider their economic, social, and environmental interrelation with the territory. Other scholars, such as Millán Vázquez de la Torre et al. (2014) [

21], focused on the role of actors, and also stressed the multiactor approach (Campón-Cerro et al., 2017 [

31]; Tregua et al., 2018 [

13]; Hernández-Mogollón et al., 2019 [

24]) and the integration of different industries such as tourism and gastronomy, aimed at the improvement of oleotourism’s image and, more in general, the design of the destination’s brand based on the territory’s identity thanks to the support from the local community (Millán Vázquez de la Torre et al., 2014) [

21] and the enhancement of local resources.

Valuable local assets represent a starting point for planning and implementing actions for local territorial competitiveness, including from a tourism perspective (Romão et al., 2013; Pysarevskyi and Meleshko, 2019 [

32]; Soare et al., 2019 [

33]). In this regard, a very interesting contribution was provided by Annoni and Kozovska (2010) [

34], who shaped the Regional Competitiveness Index and identified three pillars describing the concept of territorial sustainable competitiveness: territory—the megaproduct (Marano-Marcolini et al., 2018 [

35]; Florek and Insch, 2020 [

36]) to enhance and promote; competitiveness—the goal to be achieved to favor the local development; and sustainability—the approach to be adopted in managing and valorizing the territory considered a unique subject of development because it is a complex of social, economic, and environmental assets.

Some recent contributions to the theme underline the links between local food resources and local tourism development. In this regard, the connection between the wine industry, as well as the olive oil industry, and tourism is even more discussed in the debate over local resources as a lever to territorial enhancement and development.

Previous studies proposed models to describe the most suitable or effective methods, as well as the most relevant elements to be considered, when implementing and developing oleotourism projects and initiatives. For example, Millán Vázquez de la Torre et al. (2014) [

21] identified six actions: the coordination of local actors, the integration of tourism and gastronomy, the development of ties between the tourism industry and education actors, the improvement of the image of oleotourism through the media, the support from the local community (Loumou and Giourga, 2003 [

25]; Campón-Cerro et al., 2017 [

31]; Florek and Insch, 2020 [

36]), and the extension of seasonal demand for a positive trend throughout the year.

Through the proposed framework, the scholars analyzed oleotourists’ behavior during their visits to mills and farms, describing the tourists’ decision-making processes and identifying their motivations, satisfaction, and reasons for recommending a site, or even a destination. In detail, they highlight how seasonality can negatively affect both farming and tourism, including with reference to compatibility and sustainability issues. Therefore, tourism and farming can be mutually beneficial, as the hospitality industry can promote the development of the olive oil industry, although contextual features—such as local tourism development or the development of the olive oil industry—can strongly affect this connection.

Tregua et al. (2018) [

13] combined theoretical and empirical evidence to identify the main issue to be considered when developing oleotourism initiatives that favor local development.

Similarly, Čehić et al. (2020) [

10] detected the main elements and activities of oleotourism and, in particular, the most relevant actors to be involved in developing oleotourism projects.

In general, in most of the contributions, the actors involved and their relationships are considered extremely important. Indeed, many scholars stressed the positive outcomes of partnerships among operators from various industries (Murgado, 2013 [

37]; Millán et al., 2018 [

2]), stating that such initiatives can greatly improve customers’ experience and the quality of services. The aforementioned studies showed that the initiatives taking place—with special reference to Spain and Croatia, where our analyses were focused—are generally based on single activities without (at least in most cases) a network approach that would favor the development of this kind of tourism (Tregua et al., 2018 [

13]).

In detail, Čehić et al. (2020) [

10] provided a list of the most common initiatives dealing with olive oil both in general and focused on Croatia, while Tregua et al. (2018) [

13] suggested a set of elements to be taken into account when shaping oleotourism projects.

Accordingly, the present research will analyze current olive oil tourism activities as suggested by Čehić et al. (2020) [

10] in the three selected countries, verifying that the elements to be taken into account when shaping oleotourism activities suggested by Tregua et al. (2018) [

13] are indeed considered by local administrators and practitioners and are effective for tourism development.

3. Materials and Methods

To carry out the aim of this research, the qualitative triangulation research method was followed. Triangulation includes the use of several methods to study the same phenomenon so that the weaknesses of each one is not coupled, but their strengths are added. Use of a single method can lead to biases and methodological flaws; instead, triangulation helps to visualize a problem from different angles and, thus, increase the validity and consistency of the findings (Patton, 2014) [

38].

Denzin (2017) [

39] and Patton (2014) [

38] distinguish 4 types of triangulation: method, investigator, theory, and data source. The first type seeks to analyze the same phenomenon through various research approaches. Different qualitative techniques are generally used but can also be mixed with quantitative techniques. In the investigator triangulation, the analysis is carried out by several people, usually from different disciplines, to enrich the results. In theory triangulation, these are combined to see how different assumptions can affect the results of the same phenomenon. Finally, in data source triangulation, information from different sources or subjects is compared to create multiple perspectives for validating the data.

In particular, in this work, both primary and secondary data have been obtained. The former has been collected through 15 in-depth interviews with actors involved in the olive oil tourism sector (

Table 1). Secondary data were obtained through the review of official databases, both of an international nature and of the three countries studied, as well as relevant web pages related to the tourist and oleotourism sector. Specifically, in Spain, a review of 20 websites was carried out. Among them, 12 corresponded to oil mills that carry out oleotourism visits; the remaining websites were as follows: 2 specialized olive oil shops, 2 museums, 2 restaurants, and 2 unique accommodations. In Italy, information was collected from 20 websites; 13 corresponded to olive oil mills offering oleotourism services, 6 offered information about producers’ consortia dealing with oleotourism, and the remaining 1 website described the most important national events involving oleotourism. In Croatia, an analysis of 18 websites was carried out; among them, 5 corresponded to olive oil mills open to visitors, 1 to an olive oil museum, 2 to specialized olive oil shops, 8 to olive farms open to visitors, and 2 to fairs/events dedicated to olive oil promotion. These different data sources have required different methods of analysis, such as content analysis or observation. In this way, it can be said that both method and data source triangulation have been used in this work.

At an international level, the open databases of the International Olive Oil Council (IOC) and the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) have been used. In Spain, the following public databases have been consulted: (1) National Institute of Statistics, (2) Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, (3) Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Fisheries and Sustainable Development of the Junta de Andalucía, (4) Institute of Statistics and Cartography of Andalusia, (5) Diputación de Jaén, (6) Strategic Plan of the Province of Jaén, (7) Oleotour Jaén Project, and (8) LIFE Olivares Vivos Project. In Italy, the following were consulted: (1) Istituto nazionale di statistica (ISTAT), (2) Istituto di Servizi per il Mercato Agricolo Alimentare (ISMEA), and (3) Statista. In Croatia, the following were consulted: (1) Croatian Bureau of Statistics, (2) Paying Agency for Agriculture, Fisheries and Rural Development (APPRRR), (3) Institute for Tourism, (4) Ministry of Agriculture, and (5) Ministry of Tourism and Sport.

The research is divided into 2 parts. The first part describes the study context. In other words, a detailed description is given of the socioeconomic characteristics of the three countries related to the world of olive groves and tourism. In this way, a general vision is given of the situation in which each one finds itself and how this affects the development of the oleotourism sector. The second part presents the findings, making a compilation of the research methods used.

An effort has been made to keep the data as current as possible. Thus, the data were collected and analyzed between May and September 2020. The primary data were obtained through telephone and telematic contact.

4. Research Context

The world demand for olive oil has grown notably in recent years. In this way, the International Olive Council [

40] foresees that, in the 2019/20 campaign, the world consumption of olive oil will reach 3,094 million tons (+6.4% more as compared to the previous season). This is due mainly to the healthy properties of this product, which is the basis of the Mediterranean diet (declared, in 2010, Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO).

The olive grove is the most present permanent crop on our planet, accounting for 1% of the world’s agricultural surface. Every day of the year, olive oil is being made in some part of the world. Olive oil is produced in 57 countries on 5 continents, and is consumed in 179 countries (Vilar and Pereira, 2017) [

41].

Although traditionally producing countries are concentrated in Europe, in recent years new, non-European countries have emerged that are greatly increasing their olive oil production, such as Turkey and Morocco [

40] (

Table 2).

The olive-growing heritage is extensive in traditionally producing countries, such as Spain and Italy. This heritage includes landscapes, infrastructures, gastronomy, and local traditions. The rise of olive oil in line with this heritage favors the development of tourist activities around the culture of the olive grove. According to the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) [

3], “the growing interest of visitors in genuine cultural experiences brings along considerable opportunities but also complex challenges for tourism. The sector needs to adopt and strengthen policies and governance models that benefit all stakeholders, while preserving and further promoting the widest possible range of cultural assets and expressions.”

The characteristics of the three study countries—Spain, Italy, and Croatia—are described below, in terms of olive oil production, tourism, and heritage, so that the reality and context of these three countries can be defined for further analysis.

4.1. Spain

According to data from the International Olive Council [

40], Spain is the world’s leading producer of olive oils. In particular, production is concentrated in the autonomous community of Andalusia and specifically in the province of Jaén. In this way, during the 2017/2018 campaign, Jaén brought together 11% of world production (

Table 3). For this reason, the authors will focus mainly on this province in Spain.

Likewise, Jaén is a leader not only in production but also in cultivated area (hectares) of olive groves. Of its 1.2 million hectares, almost half (586,000) are occupied in the cultivation of olives for oil extraction (Spanish Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, 2017) [

43]. This also highlights its attractiveness in landscape terms. Thus, Jaén has 70 million olive trees, which is the highest concentration of trees in Europe (Infante-Amate, 2012) [

44] and gives it a characteristic and unique landscape in the world. In this sense, work is being done to include the olive grove landscape of Andalusia on the UNESCO World Heritage List (

http://www.paisajesdelolivar.es/) [

45].

Table 4 summarizes some outstanding data from the province of Jaén regarding the olive oil sector.

Regarding tourism, Andalusia is the Spanish autonomous community that receives the fourth-highest number of international tourists. According to data from the Spanish National Institute of Statistics (SNIE) [

47], Spain received more than 83 million tourists in 2019, of whom 12 million went to Andalusia, representing 14% of the national total. This tourism is predominantly sun and beach, with Malaga (coastal province) being the most visited.

Compared to the rest of Andalusia, Jaén is the province that receives the fewest international tourists, just 2.55% over the Andalusian total, and where there are fewer overnight stays. Visitors spend a mean of 2 days in comparison to the 9 days of Málaga, the province with the highest average stay in Andalusia (Institute of Statistics and Cartography of Andalusia, 2019) [

48].

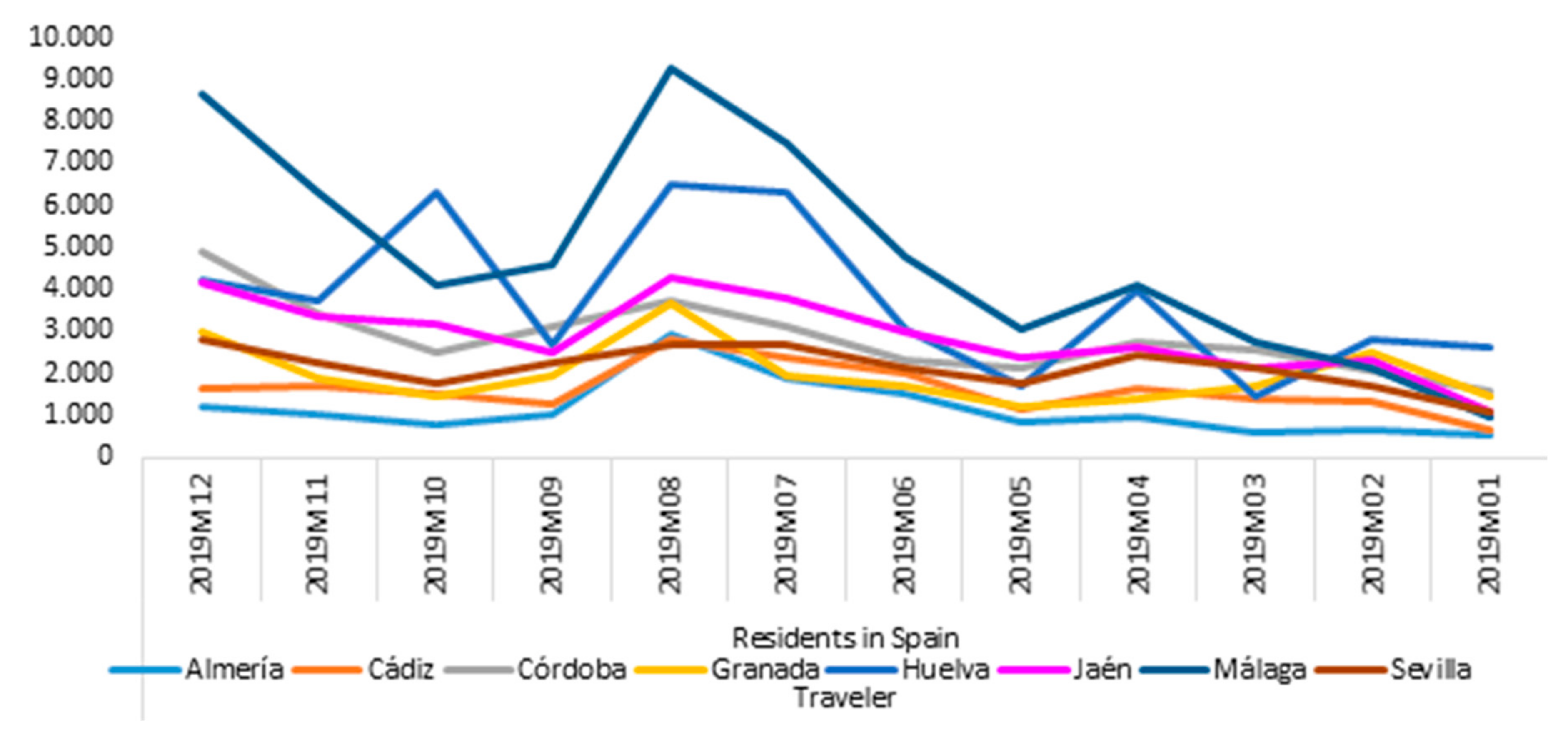

The previous data refer to a traditional occupation (hotel) and international travelers. However, if one looks at the visits of residents in Spain and occupation in rural accommodation, the data improve a lot in the province of Jaén, obtaining, in some months of the year 2019, second or third place in relation to the rest of the Andalusian provinces (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

Another aspect to be valued positively in the province of Jaén is the daily expenditure made by tourists at the destination. Compared with the rest of the Andalusian provinces, Jaén is the province where average daily spending is higher, at 79.41 euros, followed by Cádiz with 77.17 euros and Sevilla with 73.10 euros (Institute of Statistics and Cartography of Andalusia, 2019) [

48]. In addition, considering the evaluations made by tourists who travel to Andalusia in relation to its offer, Jaén is one of the best-positioned provinces. If all the study criteria are combined in a synthetic perception index, it is observed that Jaén is the province that obtains the highest score, with an index of 8.59/10 (Institute of Statistics and Cartography of Andalusia, 2019) [

48].

In this context, tourist attractions of interest stand out in the province, such as the UNESCO World Heritage cities of Úbeda and Baeza and several mountain ranges and natural parks, the most important being Cazorla, Segura, and Las Villas. In this sense, when tourists are asked their opinion about the tourist offer in Jaén, they highlight the attention and treatment received and the quality of the tourist offer of landscapes and natural parks (Strategic Plan of the Province of Jaén) [

49].

Another aspect to highlight in the province of Jaén is its strategic geographical location, as it is the country’s gateway to the Andalusian community (Strategic Plan of the Province of Jaén) [

49]. In addition, the capital of the province and city of Jaén has a large congress hall that hosts various events throughout the year. One of the most outstanding is related to the world of olive oil, i.e., the International Fair of Olive Oil and Related Industries (Expoliva), organized by the Foundation for the Promotion and Development of Olive Groves and Olive Oil, which has been held in the city of Jaén for 30 years and receives visitors from across the world. According to the Board of Directors of Fairs Jaén, in 2019 they received nearly 60,000 attendees and more than 4,000 visits from professionals from more than 70 countries.

Gastronomy is another strength of the province of Jaén in relation to olive oil as the central axis of its gastronomic tradition (Strategic Plan of the Province of Jaén) [

49]. It should be noted that, until recently, Jaén stood out in the production of olive oils in quantitative, but not qualitative, terms by selling most of the product in bulk (not packed), thus losing its distinguishing characteristics. This, fortunately, has been changing in recent years and the production of olive oils has greatly improved in quality and means of commercialization (Cohard et al., 2017) [

50]. In this way, today in Jaén, more than 300 brands of high-quality packaged olive oils are sold (Diputación de Jaén) [

51]. In this sense, in 2019, a brand from Jaén won the award for the best olive oil in the world in the Evooleum contest, which each year names the best virgin olive oils. In the published list of the 100 best oils of 2020, 81 of them are Spanish and the first three are oils from Jaén [

52]. In the Mario Solinas 2020 awards, granted by the IOC, first place also went to an oil from Jaén [

53].

Regarding quality distinctions, Jaén has the support of three Protected Denominations of Origin (P.D.O.). Likewise, for some years the Jaén olive grove sector has been working to obtain a Protected Geographical Indication (P.G.I.) for all oils from Jaén. Finally, in May 2020, the P.G.I. “Oil of Jaén” was included in the European register of Denominations of Origin (D.O.) and P.G.I. In this way, the province of Jaén became the first in Spain to have an indication of quality of this level, endorsed by the European Union for its excellence. These indications guarantee quality, safety, and production at the origin of the product, thus improving the sustainability of the crop and the attractiveness of the destination for tourists. The importance of oleotouristic routes such as the oil greenway should also be noted. This route was an old railway abandoned in the 70s and later rehabilitated for tourist uses. The road runs from the province of Jaén to the province of Córdoba, crossing olive grove landscapes, interesting infrastructures such as metal bridges and tunnels, and some lagoons classified as nature reserves (Cuesta and Moya, 2019) [

54].

4.2. Italy

Italy is one of the most important olive oil producers in Europe, together with Spain, leading the market, and Greece. Most recent projections state that olive oil production in Italy will reach 340,000 tons by 2020 (Statista.com) [

55]. Production is mainly concentrated in the south of the country, with special reference to Apulia, the leader in Italy with 193,600 tons in 2019, and the highest number of olive mills, i.e., Calabria and Sicily with 40,400 and 25,500 tons over the same year, respectively.

In this regard, it is interesting to observe that the Italian production of olive oil is expected to increase in the southern and central regions; meanwhile, in the northern regions of the country, a decreasing trend is expected, with special reference to Friuli Venezia Giulia (Statista.com) [

55].

Regarding trading trends, Italy is one of the most relevant EU exporters of olive oil, while the USA is the main importer. According to projections, in 2019/2020 exports will amount to 209,100 tons, although the COVID-19 pandemic very likely affected production as well as exportation (ISMEA) [

56].

Although Italian consumers prefer authentic Italian extra-virgin oil, with a retail sales value of almost 25 million euros during the first half of 2019, Italy imported 225,502 tons of olive oil in the first half of 2019 (almost 169,000 tons were represented by extra-virgin olive oil) to meet local consumption. Indeed, Italians are regular consumers of olive oil. In the period from October 2017 to September 2018, the domestic consumption reached 560,700 tons (Statista.com) [

55].

With reference to the aim of the present paper, recent studies showed that local administrations and firms are starting to pay attention to activities aimed at improving local development crossing food production (such as olive oil or wine) and tourist initiatives. In the last decade, the number of agritourism facilities in Italy increased significantly, from 16,600 facilities in 2010 to 20,100 in 2019. Most agritourism facilities in Italy are located in the center of the country, although most of the tourists interested in food and wine tourism in Italy travel to the south of the country (Statista.com) [

55].

Accordingly, tourists—both Italian and from other countries—interested in agritourism or, more in general, in tourism initiatives involving gastronomy and local resource production, increased in number. In this regard, in 2019, Tuscany was the Italian region recording the highest number of tourist arrivals in agritourism facilities, followed by the Autonomous Province of Bolzano and the Veneto region (ISTAT) [

57]. It must be underlined that, nowadays, oleotourism initiatives are still scarce and not very diversified (mostly oil festivals), especially in comparison to wine tourism. However, as emerged from a survey conducted in 2019, most Italian tourists interested in oleotourism activities are interested in taking part in activities related to olive oil production (Statista.com) [

55]. This data is in line with previous research (2018), according to which 75% of Italian tourists travelling domestically are interested in gastronomy (Statista.com) [

55].

However, in addition to oil festivals, which attract mostly Italians and which take place especially on weekends, there are areas such as the Lake of Garda that, with the olive oil roads, have been able to attract foreign tourists for some years now. Most of these tourists are from Germany, Austria, and Great Britain, but Scandinavian and Eastern European countries are growing strongly. On the Lake of Garda, tourism in the mills is growing and the town of Garda has about 60 producers (Consorzio di Tutela olio Extra Vergine di Oliva Garda DOP).

Another initiative that must be mentioned is the “Frantoi Aperti” in Umbria, in the center of the country, which takes place in the last days of October over 5 weekends. Local agencies offer packages to stay overnight in rural accommodations—such as farmhouses, B&Bs, country houses, or hotels—located along the Strada dell’Olio DOP Umbria. Conversely, in the rest of Italy, including in the south, where production is very high, as in Apulia, oleotourism is still in its embryonic stage.

Local administrations are paying even more attention to the opportunities that can emerge from this sector. In line with this, local actors—both public and private—are considering the oleotourism sector to be a strategic asset for the promotion of Made in Italy, and as a way to enhance local agriculture, territories, and products.

Indeed, a law was recently adopted to regulate this form of tourism; in more detail, from 1 January 2020, the provisions of law that regulated the wine tourism sector in Italy and that were published in 2017 (Legge 205/2017) have been extended to oleotourism.

The amendment is divided into three paragraphs that regulate all the activities linked to olive oil, such as production, visits to mills and the areas of cultivation, expositions of tools used for the cultivation of olive trees, and tasting and trading, including in combination with educational and recreational initiatives in the areas of cultivation and production.

4.3. Croatia

Croatia is a small Mediterranean country that stands in stark contrast to the big players, like Spain or Italy, with its modest production of olives. Remedying this shortcoming is the fact that Croatia presents the closest access point to the sea for many Central European countries; certainly, this is a strategic advantage for the development of tourism in the country.

Croatia has a long tradition of tourism. This industry is one of the most efficient and competitive. The number of total visits increases year by year; in 2019 a total of 19,566,146 foreign and domestic tourist arrivals was recorded in Croatia, of which more than 16 million visited the Adriatic part of Croatia (Croatian Bureau of Statistics 2019) [

58].

The most visited county in the Adriatic region is Istria—see

Table 5—with 4,481,698 visits in 2019, followed by Split-Dalmatia county with 3,657,001 visits (Croatian Bureau of Statistics, 2019) [

58].

Following the research of the Institute for Tourism (Tomas Ljeto, 2017) [

59], the average tourist in Croatia is between 39 and 49 years old, is higher educated, with a monthly household budget above EUR 2,000 and 3,000, is accompanied on the journey by his or her partner or family, and is typically a repeat visitor to the destination. To the destination, visitors come predominantly by personal means of transportation.

The main motive for visiting Croatia for over 50% of tourists is a passive vacation and relaxation or, rather, the 3S (sun, sand, and sea). Following the sun and beach, the most important motives for visitors are new experiences (31%) and gastronomy (29%) (Tomas Ljeto 2017) [

59]. In comparison to previous years, the motives of gastronomy and active holiday are becoming more important to tourists. In 2010, for 22% of visitors, tourist gastronomy was the main motive for entering destinations (Tomas Ljeto, 2010) [

60], while in 2014 this percentage climbed to 26% (Tomas Ljeto, 2014) [

61]. In 2017 this percentage climbed to 29% (Tomas Ljeto, 2017) [

59]. Tourists aged 30–49 tend to be more invested in gastronomy. Most visits take place in the summer months (from June to September, accounting for 87% of total visits in Croatia), which leads to higher seasonality. This is one of the problems which may be solved with the additional development of other forms of tourism, especially gastro-tourism. Following the national strategy for tourism development in Croatia, by 2020 (Strategija razvoja turizma Republike Hrvatske do 2020) [

62], gastro-tourism will have been acknowledged as a specific tourist product with great development potential. One of the goals of this strategy is to reposition Croatia as a gastro-destination following contemporary trends (Simić and Pap, 2016) [

63]. Gastro-tourism in Croatia took place sporadically, without a defined plan (Skryl et al., 2018) [

64], and based mainly upon individual stakeholder initiatives. It is necessary to initiate the strategic development of gastro-tourism, preferably, a quality promotional plan for establishing Croatia as a gastro-destination. In the last few years, the development of a new form of special-interest tourism within the framework of gastro-tourism, known as wine tourism, and a relatively new one dubbed oleotourism has taken place in Croatia.

Besides the tourism industry in Adriatic Croatia, an important source of income, especially for families in rural areas, is olive growing and olive oil production. This constitutes one of the most important agricultural activities and has been present for many centuries. Over time, the area under olive trees increased and a peak in the number of olives was recorded sometime around the 18th Century (Grković, 2005) [

65]. Following this was a steady decline in olive tree plantings brought about by various historical events and the abandonment of rural areas. An increase in olive oil production set in motion by various projects, deliberate investments to raise tree count, and the ushering in of new technology in the olive production cycle leads to a respective increase in product quality. This, in turn, is accompanied by a growing need to innovate in olive oil marketing. What sets Croatia’s olive growing apart is the tendency to produce high-quality extra-virgin olive oils, whose quality is ascribed primarily to the indigenous variety stock and pedoclimatic conditions specific to the northern Mediterranean area—most notably, the area of modern-day Istria county. A vibrant testament to this is the numerous international awards for distinguished quality. Such extra-virgin olive oils often reach high prices, making them seem elusive to the large consumer crowd in Croatia. A remedy to such a situation would be to turn to Central European and Northern European tourist consumers who regularly flood Croatia in the season—or, in other words, to establish something called an “invisible export” for olive oil supply. The formerly mentioned class of tourists is also dubbed a “high-spending profile” in the present literature (Jerasilp et al. 2019) [

66], which makes them all the more interesting. Producers are usually keen to present extra-virgin olive oils with such features directly to the customer, so as to add value to the basic product. This is typically done either by staging guided tasting tours or through a combination of more elements of experience, such as touring olive groves, olive mills, and estates alongside having the opportunity to feast on a variety of olive oils. Croatian producers, therefore, are self-engaged in oleotourism-related activities.

5. Findings

As anticipated in the previous section, data have been analyzed with reference to production, tourism, and heritage in the three countries, to highlight similarities and differences, as well as positive factors and features to be improved. Therefore, this section addresses the results for each country, then a table will summarize the comparison.

5.1. Spain

Spain is the world-leading country in terms of production. One of the key changes stemmed from the greater attention paid to quality rather than quantity. This is mirrored in the awards and the PGI certifications several firms received. These actions favored further improvement of the image of Spanish olive oil around the world, with potential positive effects on sales, new initiatives, and oleotourism. This was confirmed by one of those people in charge for tourism in Spain, who took part in the 2020 International Fair of Tourism and stated that the number of tourists attracted by olive oil is continuously increasing, with Jaén representing the ideal place for such a kind of tourism in Spain. Indeed, the interviewees with local firms offering the chance to experience olive oil as an object of tourism stressed the increasing interest of oleotourists in spas, mill visits, and interpretation centers. The authors interviewed one of the managers of a local firm, who stated:

“We noted an increasing interest in oleotourism, people are coming also from abroad; we lead them through the production site, then we move to the stock area to let them understand what is crucial in preserving the product quality. Finally, we enter the shop and the tasting room. This last stage of the visit is the most interesting for visitors, as they ask lots of questions and they have fun with the tasting sessions.”

The results are also confirmed through the statistics offered by the local territorial agency, which has been greatly involved in the development of oleotourism in recent years through both financing and training for tourism. In detail, at first, it is the private sector that plays a fundamental role in the dissemination of activities related to the culture of the olive grove, with reference to tasting sessions, agricultural tasks for tourists such as olive harvests, lodging in unique rural accommodations, oil production, etc. In turn, local administrations try to take advantage of the rich olive heritage—mainly in the province of Jaén—to improve its attraction for tourists. In this sense, the Diputación de Jaén created, in 2013, the Oleotour Jaén Project (from now on Oleotour). This project attempts a strategy of concentration of the oleotourism offer of the province as a way to give support to and boost the sector. Thus, it offers training and financial aid to the different companies attached to the project so that they can reinforce and maintain a stable and productive tourist offer. On its website, it collects different experiences that tourists can carry out throughout the world of olive oil.

Table 6 summarizes the types and quantity of experiences offered (

http://www.oleotourjaen.es/) [

67].

On the other hand, as of September 2020, those in charge of Oleotour confirmed the positive trend described at the beginning of the year by the regional Responsible for tourism in Spain, through the data on the number of visits to oil mills and to museums and interpretation centers. The following table (

Table 7) shows oleotouristic visits. Only 2019 data are shown because the current international scenario due to COVID-19 would falsify the information. Furthermore, 2020 is still not finished, so the comparison would not be balanced.

The evidence also showed an important tie to gastro-tourism and cultural tourism, as oleotourism is experienced in connection with gastronomy and the visit of the UNESCO Heritage sites of Úbeda and Baeza. In regard to gastronomy, the Interpretation Centre of Olive Oil [

68] described the relationships between various activities, such as kitchen courses, mill visits, top-class restaurants, and online courses to learn about the properties of olive oil and other ingredients. In regard to heritage, the tie was described in detail during an interview with a manager of a mill:

“Tourists visiting Úbeda and Baeza got interested [in] oleotourism, therefore if they are travelling on their own, they can add one more stage to their travel and spend [a] few hours in a mill. It often happens that they complement their cultural visit with an oleotourism experience, due to their interest in gastronomy and this novel form of tourism.”

Finally, the heritage of olive oil is part of the initiatives, as there are olive oil routes, museums, and interpretation centers with a growing number of tourists, both local and from abroad. Indeed, the word heritage was used with two meanings, namely, as what the land and the families brought from the past to the young generations dealing with olive oil, and the opportunity to consider the olive trees landscape as part of the heritage of the country and the world. These considerations were offered by the mayor of a town in Spain [

69] hosting Olive Oil Day at the end of 2018. Moreover, such an approach to olive trees and oils as part of a tradition leads to the addressing of oleotourism initiatives to another typology of visitors, namely, students, as schools and universities stimulate interest in the world of olive oil. The promotion of a culture based on olive oil as well as of events centered on this product is not addressed only to students, as universities partnered with local initiatives too, as in Málaga [

70], where the local university offers courses and promotes events together with local agencies and firms.

5.2. Italy

Olive oil production in Italy shows two opposite trends, as southern regions register the highest results in the last decade and northern regions experience a decrease. One more factor affecting production recently is Xylella, a bacterium affecting olive trees, mainly in Apulia, with several centenary trees being cut down to avoid further contagion. On the other side, oleotourism is gaining interest in various regions in Italy, mainly in the central and northern parts of the country, though it must still be considered a limited niche in the tourism industry. New facilities are being built to encourage people to experience this new form of tourism. As it was for Spain, there is a fruitful link to other forms of tourism, namely natural tourism and cultural tourism, while almost no effects are registered with reference to sea, sand, and sun tourism. A trade association in Northern Italy [

71] recalled the World Tourism Organization to confirm the mutual benefits of production and sales in the olive oil industry. Indeed, an event in 2019 referred to olive oil as a resource for culture and tourism. The increasing relevance for tourism was also confirmed by one of the mill managers who was interviewed:

“Tourists look for a set of attractions combining nature, mill, and lunch. I don’t think there is any positive effect from sea tourism, it is a totally different cluster of tourists. Therefore, firms should combine the production site or the point of sale with a small room to taste the products, but sometimes, this is not feasible due to physical constraints.”

The experience offered to oleotourists is a combination of learning and fun, as the production site is shown to explain the process of olive oil production, bottling, and storage; then the experience continues with the tasting sessions. To make the experience more attractive, some mills are offering it in the field, so that it would be something unique, in the open air to satisfy tourists’ desire for nature, as well an additional chance to further explain how the entire process occurs, from the seed to the bottle. During an interview, one of the people in charge of oleotourism described the combination of learning and fun:

“The guided tour we offer starts at the mill, then we visit the production site and a museum we set in a close building. We built this area as an ethnographic museum, because olive oil production is part of our history, not only as a family, but with reference to our subregion. The museum is mostly composed of our private collection of old machines and documents. The final part of the visit is a tasting session and we moved it out of the covered area, because it was more attractive and also because most of the visitors asked us to see the centenary trees.”

In contrast to what the authors observed in Spain, support from central and local government agencies is very limited. On the one hand, a recent law offered fiscal advantages for two additional years to oleotourism firms, and some of the measures proposed for the development of wine tourism were extended to oleotourism; on the other hand, only one of the interviewees reported receiving support in terms of communication from local agencies. This support was offered in relation to the development of an olive oil road, while most of the efforts depend on local firms and a consortium. Indeed, firms and the consortium launched some initiatives to get people interested in this form of tourism and in the olive oil road and to attract schools and cooking education centers to the production sites. For this reason, a new experience was launched, namely, the guided tasting, as the core of the visit is not the observation of the production site but the complex and key activities of understanding olive oil, with its properties, its combination with food, and the properties it brings.

Finally, a relevant initiative called “Frantoi Aperti” (Open Mills) has been carried out in Central Italy since 1988. Visitors are offered the chance to experience rural tourism during one of the most important months for the olive crop. During the six weekends of the initiative, various forms of tourism are combined. Thus, visitors can experience food, local tradition, theatres, and historical buildings. Olive oil is the main protagonist of this initiative, with treks around olive trees, conventions to describe the relevance of olive oil from a health perspective, educational kitchen courses for young visitors, and exhibitions of old machines, photos, and videos to track back and show the history of olive oil production in the region. This initiative is also centered on the Mediterranean diet, as olive oil plays a relevant role in it. The evidence shows that this is the only tie to industrial heritage, apart from visits including the observation of old tools and machines, and the trees themselves, dating back to the 19th century.

Therefore, tourism initiatives are figuratively considered by a magazine [

72] for professionals in the agri-business as a launchpad for the entire industry. As emerged from the description of “Frantoi Aperti” through the website, and in line with the most frequent comments from tourists, “novelty” and “relax” are the keywords of oleotourism in Italy, as people are attracted by this new form of tourism and the setting in which the experience occurs creates a sense of relaxation due to the natural elements and the visit to the countryside.

5.3. Croatia

Olive oil production in Croatia registered relevant increases recently, in both quantity and quality. Regarding quality, various PGI certifications have been awarded. On the one hand, new trees were planted in recent years and firms made significant efforts to increase and improve production; on the other hand, centenary trees underwent a program promoted to their care and preservation, with positive results. Owing to development in the last 30 years, the olive sector has experienced change. In Croatia, new orchards have been planted, the existing centennial trees have undergone revitalization, and new technologies have been incorporated into the process of olive growing. In Croatia, in the year 2018, there were 18,679 ha of olive groves, producing a total of 28,418 t of olives and overall 36,573 hl of olive oil (Croatian Bureau of Statistics, 2018) [

58]. Countries with the greatest extent of land under olive groves are Istrian country with 3,648 ha and Split-Dalmatia county with 4,898 ha (APPRRR, 2017) [

73]. Some additional figures provide further evidence of the interest in the oleotourism experience and the number of initiatives recently developed; indeed, previous research (Čehić et al., 2020) [

10] showed—among other things—a high number of farms open to visitors, museums, and roads, as in the

Table 8.

The efforts performed by farmers are mirrored in international recognitions, as mentioned above, with awards given in international fairs and by an international association for organic olive oils. Moreover, market experts have recognized the positive results and customer satisfaction with Croatian olive oils in Central Europe.

The geographical position of Croatia has created an advantage for tourism in general, as people from some nearby countries, with no seaside, go to Croatia for holidays. It should be noted that the interviewees did not acknowledge the role of sea, sand, and sun tourism in the development of oleotourism. The responses that the authors received from the actors in this business confirmed a growing interest in oleotourism due to it being novel and capturing the attention of people interested in gastronomy. This tie is also confirmed by a trend in restaurants, with people buying olive oil after lunch or dinner to bring it home. Therefore, there is a general growing interest in olive oils in Croatia, as was confirmed during one of the interviews:

“We recently built a new olive oil mill and a big tasting room; this is our answer to the increase in production and to the growing interest in oleotourism. We planned to build them one next to the other because they have to be connected to enrich the visit, and both of them are located in an area that is easy to be reached from the main highway, therefore visitors would not struggle to find us and start their visit.”

Besides being recently developed, oleotourism in Croatia consists of a good variety of offerings in terms of tours. Additionally, recent data confirmed the success of new initiatives. Indeed, the Croatia National Bureau of Statistics (2019) [

58] highlighted the growth of Istria County for incoming tourists and observed relevant growth in oleotourism, too. Consequently, oleotourism may be considered a prospective special interest form of tourism in Croatia. One key piece of data is the number of tourists who engage in oleotourism during their journey in Croatia: 9.1% of tourists experienced the olive oil road, with most of them being visitors aged 50 or above and accompanied by family members. The observation of the offering produced evidence of the following details: concretely, some tours are based mostly on the farm, while others are centered on the tasting experience. One of the operators whom the authors interviewed described the offering in the following way:

“Our farm is open all year long. The peak for visits is in summer, with an average of 50 persons per day, most of them coming from abroad. We studied what visitors want and appreciate most, therefore we set three tours, with a different combination of activities and with different duration[s]. We feel tourists can find the solution that best fits with their needs.”

The visits also represent a source of revenue in the long run, as most tourists buy something during the guided tours and some of them—especially foreign tourists—continue buying olive oils via online shops throughout the rest of the year. Additionally, one of the most recent interviews that the authors conducted showed encouraging results despite the problems that farmers experienced due to the pandemics in the first semester of 2020. Indeed, the results are not too bad considering the lockdown, and as soon as the restrictions were lifted, tourists started visiting again the farms, as described in the following excerpt:

“We were worried when in March the pandemics affected us. We experienced negative results as most of the firms in the tourism business here. Anyway, when we opened the farm to visitors in June, we reached good results in terms of visits and sales. The summer is almost over and we think the remaining months of this year can give us some more opportunities to recover what we lost in the first semester.”

Finally, routes were proposed to lever the relationship between natural tourism and cultural tourism; indeed, these initiatives were planned to combine heritage, history, and sustainable tourism. The support of the Ministry of Tourism played a key role in furthering these routes, as efforts were made to join local farmers and share ideas and experiences. Moreover, the Ministry set the ground for creating a network for oleotourism with nearby countries, to increase awareness of this new form of tourism. In Croatia, different types of stakeholders are involved in oleotourism activities; most of them are olive producers and owners of olive mills, though lately tourist companies have expanded their primary business in the olive sector. However, local authorities, too, have encouraged the development and sustainability of rural areas implementing the olive oil road, which has connected all the stakeholders involved in this supply chain. In the same vein, efforts have been made to increase the popularity and visibility of museum and interpretation centers. A confirmation of the last statement depends on the holistic description that the “Museum Olei Histriae” offers on its official website [

74]: “The House of Istrian Olive Oil tells the story of olive growing in Istria through history up to the present day. You can also find out how the ancient Romans processed olive oil and how it is produced today. Discover all the aromas and tastes, as well as the chemical composition of Istrian extra-virgin olive oil and learn how olive oil, combined with the Mediterranean diet affect our health.”

The key results are summarized in the next table (

Table 9) to stress the three areas to which we referred and how they differ with reference to the three countries. Indeed, production, tourism, and heritage are the main aspects we recall to describe the three scenarios, favoring a comparison among them, and showing the mutual influence they have on oleotourism.

6. Discussion and Implications

Mediterranean countries that are members of the EU constitute over 60% of the world’s total olive oil output, with Spain leading them. Some years earlier, the share was even larger. However, with the emergence of producer countries such as Turkey, Morocco, and Tunisia, followed by Australia and the USA outside the Mediterranean basin, it has been dropping. Clearly and notably, the Mediterranean’s connection to its olives, olive oil, and its signature diet will, notwithstanding current market changes, always comprise an inseparable and well-balanced unity that involves several intertwined sustainable elements, such as tourism, gastronomy, cultural heritage, and agriculture. Thus, it is understandable that oleotourism has seen substantial growth in the Mediterranean, as tourists there are offered a specific and complex tourism product. Considering Spain, Italy, and Croatia, the three Mediterranean countries upon which this research is based due to their results in terms of top-quality production, it is observed that the oleotourism activities offered are strongly related to the enjoyment of experiences in a traditional local environment. This is related to studies that classify oleotourism as a type of special interest tourism, characterizing it with indicators such as sustainability, experience, the promotion of local culture, and the image of prestige/status (Parrilla-González et al., 2020 [

16]; Pulido-Fernández et al., 2019 [

15]).

Regarding sustainability, in the countries analyzed, it is seen how oleotourism has not led to notable changes in the environment. Apart from the fact that oleotourism is a form of tourism that is still growing, the desire of visitors to live an authentic experience in the territory and to learn about local customs and practices promotes this sustainable development. In the different offers analyzed in the countries studied, it is seen how local industries and businesses are integrated within the oleotourism routes (mainly restaurants, shops, and rural accommodation) while promoting and preserving the natural environment in a respectful way. In the same way, the development of local communities that host this type of activity is encouraged, promoting employment in the area; this is mirrored in the areas where the government took part in supportive interventions, as was the case with local governments (in Spain), the central government (in Croatia), and the recent proposal of an ad hoc law (in Italy). In this way, a certain economic, social, and environmental interaction of oleotourism with the territory is observed—necessary conditions, according to authors such as Pulina et al. (2006) [

29], for oleotourism development in a sustainable way. The authors see another notable relationship with sustainability in the rise of protected designations of origin. This characteristic integrates the different industries under a common name that is a guarantee of production in origin and quality; Spain, as well as Croatia, showed higher attention paid to the quality of production, as a lever for the market and the image of the whole industry. This helps in the creation of a brand-region, the identity of a territory, and, thus, the improvement of oleotourism’s image (Campón-Cerro et al., 2017 [

31]; Tregua et al., 2018 [

13]; Hernández-Mogollón et al., 2019 [

24]).

There are mutual differences and similarities among the three countries studied. First, they compare differently as per area, or land size, which is a predetermining factor in quantity output. In this respect, Croatia’s production output is almost negligible when scaled against the world’s leaders in olive oil production—Spain and Italy. A point held in common by all three countries involved is that tourism comprises a large section of the GDP. When analyzed, it becomes obvious that the range and availability of oleotourism differ in these countries. An important driver here is the local, regional, and national self-government that play a significant role in driving and incentivizing new initiatives and projects. The range of oleotourism is most developed in Spain, and somewhat less so in Italy and Croatia. A large portion of initiatives in the oleotourism sector is run primarily by private businesses, chief among which are those that ordinarily produce olive oil and that, via tourism, are seeking to add value to their products. This is done by means of direct sales and organizing several guided tours that open a novel world of experiences to customers. These experiences include guided olive oil tasting, sharing information on olive growing, and the production process. Recent changes to the tourism market and the ever-growing interest in local gastronomy and culture certainly go hand in hand with oleotourism development. It ought to be highlighted that a major problem for most Mediterranean countries is seasonality, which strikes Croatia particularly harshly, as the overwhelming share of tourism exchange is done during the summer months. Taking into account the olive tree’s biology and the time-frame within which harvest occurs—October to December—it can be said that activities such as the harvest and production of fresh olive oil alone, if preceded by appropriate advertising, may significantly boost arrivals to a Mediterranean destination well beyond the summer months, thus driving tourism-related activities all year round. Thus, Martín-Martín et al. (2020) [

14] concluded that some rural destinations suffer from less seasonality than urban or cultural destinations, although each destination may have specific conditions that must be previously analyzed.

Theoretical implications foremost address the methodological approach in the paper. Specifically, the authors have employed data sources and the triangulation method. Due to the demanding research process, there is a relative scarcity of papers conducting a comparison of multiple countries. For this reason, and to gain new insights by contrasting three countries, the authors have engaged with the infrequent research matter at hand. The paper has built upon previous scholarly contributions by the authors (Čehić et al. 2020 [

10]; Tregua et al., 2018 [

13]) to widen the knowledge about, and scope of, oleotourism. Highlighted elements or requirements for establishing a range of oleotourism goods and services in Čehić et al. (2020 [

10]) have also been employed in a comparative approach to three countries so as to objectively assess the case of each country. Through application of such a systematic approach, the data have been rendered more accurate, and a methodological framework has been generated which may prove applicable to the cases of other countries with the intended purpose of assessing the oleotourism development stage and identifying activities required for developing further said type of special interest tourism.

Practical application of this paper is evident in more than a few aspects. A clear-cut analysis of the situation in all three countries has been made in which mutual similarities and differences have been noted for all three countries in view of oleotourism. By contrasting Spain, Italy, and Croatia with other Mediterranean countries and countries outside the Mediterranean basin that are increasingly producing more olive oil, it is possible to draw valuable information based solely on the fact that the former three countries differ considerably, and for that, they may serve as a case study for a greater number of countries that are pursuing oleotourism. By fusing rural spaces, i.e., the specific locality where olives are grown, with tourism, firms are establishing a green-oriented opportunity for economic development at lesser destinations in Mediterranean countries. This, in fact, means that said rural, often isolated areas, become open to the possibility of development. Simultaneously, resources and the environment are protected by the promotion of green and sustainable farming practices, i.e., olive growing as traditional agricultural production in the Mediterranean area. Tourism is broadly an important economic branch for the vast majority of Mediterranean countries. Hence, innovation and new tourist offerings such as oleotourism may increase revenue by attracting new market segments that are particularly interested in culinary tourism. Policy-makers should approach an integrated scheme of policy planning that is bound to increase profits from tourism-related activities under the condition of sustainable resource management, with an indirect benefit to the olive growing sector. Incentives to businesses in the form of entrepreneurial education, wide-scope promotions, and financial support for establishing oleotourism-related activities ought to comprise an integral component of the budget at a local or regional government level.

Owing to this research and the comparative approach within it, stakeholders who seek to draw their own development of oleotourism may do so more objectively and with a higher quality rate by planning marketing activities and branding their range of oleotourism specifically suited to Mediterranean countries. Proactive planning and identifying strategic objectives in the case of each above-mentioned country are the key steps to future oleotourism development. It is evident that a certain group of stakeholders within all three countries is increasingly diversifying (Parrilla-González et al., 2020) [

16] its core business and bonding it to tourism (Pulido-Fernández et al., 2019) [

15]. This enables the system to be economically sustainable. In general, oleotourism supports three sustainability pillars—economic, environmental, and social. Oleotourism is an activity that notably occurs in rural areas, fostering the growth of the local economy, new workplaces and opportunities, and concern for the environment, with special reference to olives valued as cultural goods of the Mediterranean. Hence, oleotourism is a consolidating activity that drives sustainable growth and rational resource allocation, and that is considered to be vital to the development of Mediterranean countries. Also, the fact that the Mediterranean diet was registered on UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage List in 2013 speaks in favor of oleotourism as such, and may be considered of additional value in branding olives, olive oil, and the Mediterranean area within the framework of oleotourism.

The predominance of the private initiative over the public is a common characteristic that limits the development of oleotourism. In all cases, joint marketing networks should be promoted, which configure closed tourist products attractive to the different segments, as well as the participation of the entire local community (Millán Vázquez de la Torre et al., 2014 [

21]; Campón-Cerro et al., 2017 [

31]; Florek and Insch, 2020 [

36]). Moreover, due to the novelties of oleotourism and the mutual effect with other activities (i.e., sales, cultural tourism, and hospitality) support from the central and local governments would be needed. More in detail, firms need to fill the managerial gap due to the performance of a new activity, and the promotion of this new form of tourism would be helpful to encourage visitors to experience it. The setup of olive oil roads, the launch of events, and the identification of tourism paths would all help olive oil producers expand their business.

7. Conclusions

In this work, a comparative analysis between countries (cross-national) has been carried out in relation to the development of oleotourism. Specifically, this research presents the cases of Croatia, Italy, and Spain—three countries traditionally producing olive oils that, taking advantage of the resources generated by the sector, have carried out a productive diversification of their rural areas. The objective of the work has been to analyze the key elements that favor the development of oleotourism in the three countries, identifying their similarities and differences.

To achieve this goal, the triangulation method has been used, that is, combining several data sources. Relevant sources of data for the three countries have been cited from various websites and publicly available data from state agencies, ministries, institutes, and statistical yearbooks, as well as interviews with stakeholders involved in oleotourism.

The results of these analyses allow the authors to stress three main themes related to the evidence, namely, the comparison (as per the aim of this research), the limitations of this business, and ties to sustainability.

First and foremost, we can state that, although each of the three countries is in a different stage of development, they all have elements that seem to be common to this type of tourism: the ties to natural-based tourism, the efforts of businesses, and concrete or at least foreseeable support from the government. This may be relevant in establishing guidelines to build the foundations of oil tourism in emerging countries.

Secondly, there are elements that somewhat limit the development of oleotourism. Seasonality, lack of marketing and communication, little professionalization, or lack of institutional support appear to be common limitations in all three cases; in any event, an increase in the variety of offers in Spain, some innovative ideas in Italy, and the demand from nearby countries in Croatia seem to potentially counteract the limitations.

Finally, oleotourism can be characterized as a form of sustainable tourism, given the preservation of local customs and landscapes, the participation of the resident community, or the development of quality and food safety labels. Businesses are aware of this and they establish interventions and offerings respecting natural resources and tradition, thus aligning the needs of the environment with the proposal of an immersive and novel experience in this niche market.

In future research, it would be interesting to carry out this analysis from a demand perspective. Considering the different levels of oleotourism development in the three countries examined, the level of involvement and satisfaction of visitors in each case could be analyzed. Another aspect of interest to be analyzed further is the influence of other types of tourism on the simultaneous demand for oil tourism products. This could help in the configuration of closed tourist packages that would lead to an increase in demand, in the number of both visitors and overnight stays, therefore boosting the average daily expenditure. This work is also susceptible to replication in other countries, both traditional and emerging.

The main limitations found during this investigation are as follows: on the one hand, the difficulty in establishing contacts and conducting face-to-face interviews due to the current situation caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and, on the other hand, the fact that tourist activity has been strongly reduced, which is why some data offered by the official databases consulted (mainly as of March 2019) have been affected.