The Impact of Micro and Macro Level Factors on the Working and Living Conditions of Migrant Care Workers in Italy and Israel—A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Rationale for Comparing Italy and Israel

1.3. Aims and Research Question

What are the scope, main topics, and gaps in the existing academic literature on how micro and macro level indicators detailed in the MFTCM impact the working and living conditions and opportunities of live-in MCWs in Italy and Israel?

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

- Identifying the research question;

- Identifying relevant studies;

- Study selection;

- Charting the data;

- Collating, summarizing and reporting the results.

3. Results

Themes

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of This Review

4.2. Links to the Existing Literature

4.3. Implications for Policy and Practice

4.4. Areas for Future Research

4.5. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Section | Item | Prisma-Scr Checklist Item | Reported On Page # |

|---|---|---|---|

| Title | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a scoping review. | 1 |

| Abstract | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary that includes (as applicable): background, objectives, eligibility criteria, sources of evidence, charting methods, results, and conclusions that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 1 |

| Introduction | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. Explain why the review questions/objectives lend themselves to a scoping review approach. | 4–5 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the questions and objectives being addressed with reference to their key elements (e.g., population or participants, concepts, and context) or other relevant key elements used to conceptualize the review questions and/or objectives. | 5 |

| Methods | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate whether a review protocol exists; state if and where it can be accessed (e.g., a Web address); and if available, provide registration information, including the registration number. | 5 |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify characteristics of the sources of evidence used as eligibility criteria (e.g., years considered, language, and publication status), and provide a rationale. | 6 |

| Information sources * | 7 | Describe all information sources in the search (e.g., databases with dates of coverage and contact with authors to identify additional sources), as well as the date the most recent search was executed. | 6 |

| Search | 8 | Present the full electronic search strategy for at least 1 database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | 28 |

| Selection of sources of evidence † | 9 | State the process for selecting sources of evidence (i.e., screening and eligibility) included in the scoping review. | 6 |

| Data charting process ‡ | 10 | Describe the methods of charting data from the included sources of evidence (e.g., calibrated forms or forms that have been tested by the team before their use, and whether data charting was done independently or in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | 7 |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought and any assumptions and simplifications made. | 7, 11 |

| Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence § | 12 | If done, provide a rationale for conducting a critical appraisal of included sources of evidence; describe the methods used and how this information was used in any data synthesis (if appropriate). | N/A |

| Synthesis of results | 13 | Describe the methods of handling and summarizing the data that were charted. | 14 |

| Results | |||

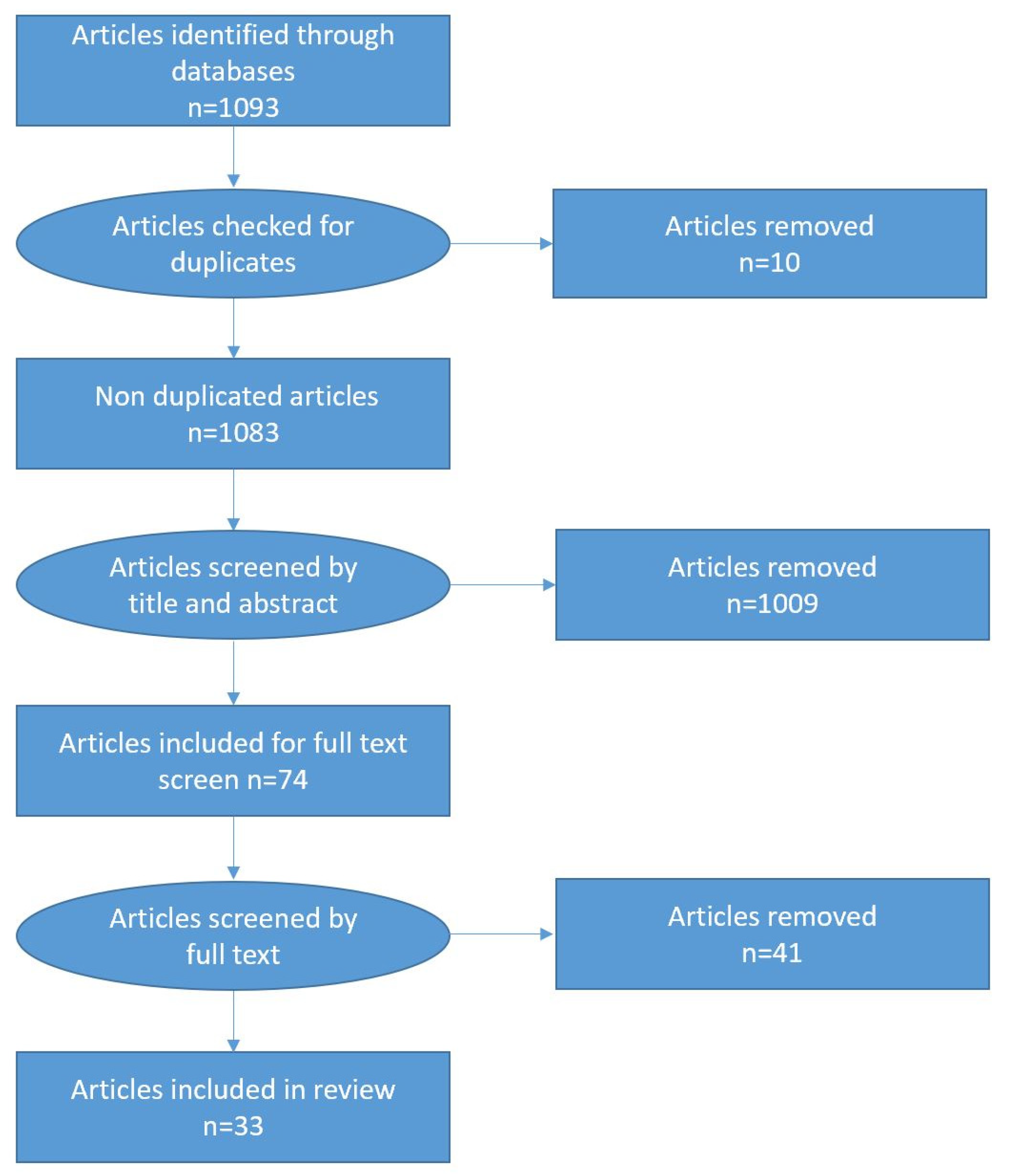

| Selection of sources of evidence | 14 | Give numbers of sources of evidence screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally using a flow diagram. | 6–7 |

| Characteristics of sources of evidence | 15 | For each source of evidence, present characteristics for which data were charted and provide the citations. | 7–14 |

| Critical appraisal within sources of evidence | 16 | If done, present data on critical appraisal of included sources of evidence (see item 12). | N/A |

| Results of individual sources of evidence | 17 | For each included source of evidence, present the relevant data that were charted that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 7–14 |

| Synthesis of results | 18 | Summarize and/or present the charting results as they relate to the review questions and objectives. | 15–21 |

| Discussion | |||

| Summary of evidence | 19 | Summarize the main results (including an overview of concepts, themes, and types of evidence available), link to the review questions and objectives, and consider the relevance to key groups. | 21–24 |

| Limitations | 20 | Discuss the limitations of the scoping review process. | 25 |

| Conclusions | 21 | Provide a general interpretation of the results with respect to the review questions and objectives, as well as potential implications and/or next steps. | 25–26 |

| Funding | |||

| Funding | 22 | Describe sources of funding for the included sources of evidence, as well as sources of funding for the scoping review. Describe the role of the funders of the scoping review. | 26 |

Appendix B. Boolean Operators Used

Appendix C. References Including for Mapping and Thematic Analysis

- Ayalon, L.; Halevy-Levin, S.; Ben-Yizhak, Z.; Friedman, G. Personal home care workers’ role in hospital: a qualitative study. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy 2015, 20, 217–223, doi:10.1177/1355819615577807.

- Fusco, S.; Corsonello, A.; Chiatti, C.; Fabbietti, P.; Salerno, G.; De Bonis, E.; Corica, F.; Lattanzio, F. Migrant care workers and rehospitalization among older patients discharged from acute care hospitals. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2015, 15, 196–203, doi:10.1111/ggi.12254.

- Green, O.; Ayalon, L. Whose right is it anyway? Familiarity with workers’ rights among older adults, family caregivers, and migrant live-in home care workers: implications for policy and practice. Educational Gerontology 2015, 41, 471–481.

- Mazuz, K. Elderly care between global and local services: The use of somatic care practices. BMJ Case Rep. 2015, 2015, doi:10.1136/bcr-2015-211055.

- Meyer, P. Relations of Care: The Contexts for Immigrant Care Workers in Northern Italy. Antropol. Work Rev. 2015, 36, 2–12, doi:10.1111/awr.12054.

- Ayalon, L.; Roziner, I. Satisfaction with the relationship from the perspectives of family caregivers, older adults and their home care workers. Aging Ment. Health 2016, 20, 56–64, doi:10.1080/13607863.2015.1020412.

- Barbabella, F.; Chiatti, C.; Rimland, J.M.; Melchiorre, M.G.; Lamura, G.; Lattanzio, F. Socioeconomic Predictors of the Employment of Migrant Care Workers by Italian Families Assisting Older Alzheimer’s Disease Patients: Evidence From the Up-Tech Study. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2016, 71, 514–25, doi:10.1093/geronb/gbv045.

- Boccagni, P. Searching for well-being in care work migration: Constructions, practices and displacements among immigrant women in Italy. Soc. Polit. 2016, 23, 284–306, doi:10.1093/sp/jxv031.

- Green, O.; Ayalon, L. Whom Do Migrant Home Care Workers Contact in the Case of Work-Related Abuse? An Exploratory Study of Help-Seeking Behaviors. J. Interpers. Violence 2016, 31, 3236–3256, doi:10.1177/0886260515584347.

- Kemp, A.; Kfir, N. Wanted Workers but Unwanted Mothers: Mobilizing Moral Claims on Migrant Care Workers’ Families in Israel. Social Problems 2016, 63, 373–394, doi:10.1093/socpro/spw016.

- Baldassar, L.; Ferrero, L.; Portis, L. ‘More like a daughter than an employee’: the kinning process between migrant care workers, elderly care receivers and their extended families. Identities 2017, 24, 524–541, doi:10.1080/1070289X.2017.1345544.

- Cordini, M.; Ranci, C. Legitimising the care market: The social recognition of migrant care workers in Italy. Journal of Social Policy 2017, 46, 91–108, doi:10.1017/S0047279416000398.

- Palumbo, L. Exploiting for Care: Trafficking and Abuse in Domestic Work in Italy. J. Immigr. Refugee Stud. 2017, 15, 171–186, doi:10.1080/15562948.2017.1305473.

- Rugolotto, S.; Larotonda, A.; van der Geest, S. How migrants keep Italian families Italian: badanti and the private care of older people. Int. J. Migr. Health Soc. Care 2017, 13, 185–197, doi:10.1108/ijmhsc-08-2015-0027.

- Scrinzi, F. Caring for the elderly in the family or in the nation? Gender, women and migrant care labor in the Lega Nord. West Eur. Polit. 2017, 40, 869–886, doi:10.1080/01402382.2017.1287447.

- Boccagni, P. At home in home care? Contents and boundaries of the ‘domestic’ among immigrant live-in workers in Italy. Hous. Stud. 2018, 33, 813–831, doi:10.1080/02673037.2017.1367366.

- Bonatti, V.; Muniandy, P. Defiant aspirations: Migrant women’s struggles for stability and upward mobility in Naples and Kuala Lumpur. Migr. Stud. 2018, 8, 113–130, doi:10.1093/migration/mny039.

- Cherubini, D.; Geymonat, G.G.; Marchetti, S. Global rights and local struggles: The case of the ILO convention N.189 on domestic work. Partecip. Confl. 2018, 11, 717–742, doi:10.1285/i20356609v11i3p717.

- Green, O.; Ayalon, L. Violations of workers’ rights and exposure to work-related abuse of live-in migrant and live-out local home care workers—a preliminary study: implications for health policy and practice. Isr J Health Policy Res 2018, 7, 32, doi:10.1186/s13584-018-0224-1.

- Nicolescu, G. From border fetishism to tactical socialism. East Cent. Eur. 2018, 45, 279–299, doi:10.1163/18763308-04502005.

- Bronstein, J. A transitional approach to the study of the information behavior of domestic migrant workers: A narrative inquiry. J. Doc. 2019, 75, 314–333, doi:10.1108/JD-07-2018-0112.

- Brown, R.H. Reproducing the national family: kinship claims, development discourse and migrant caregivers in Palestine/Israel. Fem. Theory 2019, 20, 247–268, doi:10.1177/1464700119833039.

- Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Golander, H.; Iecovich, E.; Jensen, B. Social Engagement Care for Frail Older Persons: Desire for It and Provision by Live-In Migrant Caregivers. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2019, 74, 1062–1071, doi:10.1093/geronb/gbx052.

- Golan, O.; Babis, D. Towards professionalism through social networks: constructing an occupational community via Facebook usage by temporary migrant workers from the Philippines. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2019, 22, 1230–1252, doi:10.1080/1369118X.2017.1411520.

- Ranci, C.; Arlotti, M. Resistance to change. The problem of high non-take up in implementing policy innovations in the Italian long-term care system. Policy Soc. 2019, 38, 572–588, doi:10.1080/14494035.2019.1619995.

- Nicolescu, G. Keeping the elderly alive global: Entanglements and embodied practices in long-term care in southeast Italy. Anthropology Aging 2019, 40, 77–93, doi:10.5195/aa.2019.202.

- Solari, C.D. Transnational moral economies: The value of monetary and social remittances in transnational families. Curr. Sociol. 2019, 67, 760–777, doi:10.1177/0011392118807531.

- Shinan-Altman, S.; Ayalon, L. Perceived control among migrant live-in and local live-out home care workers in Israel. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 23, 189–195, doi:10.1080/13607863.2017.1401584.

- Scrinzi, F. Beyond “Women’s Work”: Gender, Ethnicity, and the Management of Paid Care Work in Nonprofit Domiciliary Services in Italy. J. Immigr. Refugee Stud. 2019, 17, 441–456, doi:10.1080/15562948.2018.1538472.

- Teshuva, K.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Iecovich, E.; Golander, H. Like one of the family? Understanding relationships between migrant live-in care workers and older care recipients in Israel. Ageing and Society 2019, 39, 1387–1408, doi:10.1017/S0144686 × 1800003X.

- Vianello, F.A.; Finotelli, C.; Brey, E. A slow ride towards permanent residency: legal transitions and the working trajectories of Ukrainian migrants in Italy and Spain. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2019, doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1590187.

- Casanova, G.; Principi, A.; Lamura, G. Social innovation in long-term care: Lessons from the Italian case. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, doi:10.3390/ijerph17072367.

- Holler, R. Material, stigmatic, and agentic dimensions in the experience of claiming disability benefits: The Israeli case. Soc. Policy Adm. 2020, doi:10.1111/spol.12578.

References

- World Health Organization. AIDS Home Care Handbook; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, F. Converging Variations in Migrant Care Work in Europe. J. Eur. Soc. Policy 2012, 22, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigante, V. Informal Care in Europe: Exploring Formalisation, Availability and Quality; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, D. Policy Brief.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2012; ISBN 0022-1465. [Google Scholar]

- Krol, M.; Papenburg, J.; van Exel, J. Does Including Informal Care in Economic Evaluations Matter? A Systematic Review of Inclusion and Impact of Informal Care in Cost-Effectiveness Studies. Pharmacoeconomics 2015, 33, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, A. European Care Regimes and the Role of Migrant Care Workers within Them. J. Popul. Ageing 2012, 5, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bom, J.; Bakx, P.; Schut, F.; van Doorslaer, E. Health Effects of Caring for and about Parents and Spouses. J. Econ. Ageing 2019, 14, 100196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinquart, M.; Sörensen, S. Spouses, Adult Children, and Children-in-Law as Caregivers of Older Adults: A Meta-Analytic Comparison. Psychol. Aging 2011, 26, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbakel, E. How to Understand Informal Caregiving Patterns in Europe? The Role of Formal Long-Term Care Provisions and Family Care Norms. Scand. J. Public Health 2018, 46, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaschowitz, J.; Brandt, M. Health Effects of Informal Caregiving across Europe: A Longitudinal Approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2017, 173, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litwin, H.; Stoeckel, K.J.; Roll, A. Relationship Status and Depressive Symptoms among Older Co-Resident Caregivers. Aging Ment. Health 2014, 18, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relationship-Based Home Care: A Sustainable Solution for Europe’s Elder Care Crisis; Global Coalition on Aging: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–36.

- King-Dejardin, A. The Social Construction of Migrant Care Work: At the Intersection of Care, Migration and Gender; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Spasova, S.; Baeten, R.; Coster, S.; Ghailani, D.; Peña-Casas, R.; Vanhercke, B. Challenges in Long-Term Care in Europe: A Study of National Policies 2018; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; ISBN 92-79-87174-9. [Google Scholar]

- Mot, E.; Geerts, J.; Willeme, P. Long-Term Care Use and Supply in Europe: Projection Models and Results for Germany, the Netherlands, Spain and Poland; Centre for European Policy Studies: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Population Prospects 2019: Highlights; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–1238.

- Van Hooren, F. Migrant care work in Europe: Variety and institutional determinants. In The Transformation of Care in European Societies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 62–82. [Google Scholar]

- Osservatori Statistici e Altre Statistiche. Available online: https://www.inps.it/osservatoristatistici/12/o/350 (accessed on 31 December 2020).

- Informal Economy Workers. Available online: http://www.ilo.org/global/topics/wages/minimum-wages/beneficiaries/WCMS_436492/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- The Value of Domestic Work: The Economic and Social Role of Employer Families; Associazione Nazionale Famiglie Datori di Lavoro Domestico: Rome, Italy, 2018; pp. 1–78.

- Nathan, G. The OECD Expert Group on Migration SOPEMI Annual Report: International Migration—Israel 2018–2019; Ruppin Academic Center: Emek Hefer, Israel, 2019; pp. 1–153. [Google Scholar]

- Mundlak, G.; Shamir, H. Organizing Migrant Care Workers in Israel: Industrial Citizenship and the Trade Union Option. Int. Labour Rev. 2014, 153, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, A.; Kfir, N. Wanted Workers but Unwanted Mothers: Mobilizing Moral Claims on Migrant Care Workers’ Families in Israel. Soc. Probl. 2016, 63, 373–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Roit, B. Changing Intergenerational Solidarities within Families in a Mediterranean Welfare State: Elderly Care in Italy. Curr. Sociol. 2007, 55, 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, G. Private Assistants in the Italian Care System: Facts and Policies. Obs. Soc. Br. 2013, 14, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courbage, C.; Montoliu-Montes, G.; Wagner, J. The Effect of Long-Term Care Public Benefits and Insurance on Informal Care from Outside the Household: Empirical Evidence from Italy and Spain. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2020, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Indennità di Accompagnamento per Invalidi Civili. Available online: https://www.inps.it/nuovoportaleinps/default.aspx?itemdir=50194 (accessed on 31 December 2020).

- Indennità di Accompagnamento—Ciechi Civili Assoluti. Available online: https://www.inps.it/nuovoportaleinps/default.aspx?itemdir=50081 (accessed on 31 December 2020).

- Barbabella, F.; Chiatti, C.; Rimland, J.M.; Melchiorre, M.G.; Lamura, G.; Lattanzio, F. Socioeconomic Predictors of the Employment of Migrant Care Workers by Italian Families Assisting Older Alzheimer’s Disease Patients: Evidence from the Up-Tech Study. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2016, 71, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regev-Messalem, S. Stories of Dependency and Power: The Value of Live-In Elder Care in Israel. Socius 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, H. Migrant Care Workers in Israel: Between Family, Market, and State. Isr. Stud. Rev. 2013, 28, 192–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benefit Levels and Selection Options—Long-Term Care. Available online: http://www.btl.gov.il:80/English%20Homepage/Benefits/LongTerm%20Care/levels/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 13 November 2020).

- Borowski, A. Israel’s Long-Term Care Social Insurance Scheme after a Quarter of a Century. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2015, 27, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, G.; Principi, A.; Lamura, G. Social Innovation in Long-Term Care: Lessons from the Italian Case. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Women on the Move: Migration, Care Work and Health; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Decent Work. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/decent-work/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 31 December 2020).

- Palumbo, L. Exploiting for Care: Trafficking and Abuse in Domestic Work in Italy. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2017, 15, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugolotto, S.; Larotonda, A.; van der Geest, S. How Migrants Keep Italian Families Italian: Badanti and the Private Care of Older People. Int. J. Migr. Health Soc. Care 2017, 13, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, O.; Ayalon, L. Whom Do Migrant Home Care Workers Contact in the Case of Work-Related Abuse? An Exploratory Study of Help-Seeking Behaviors. J. Interpers. Violence 2016, 31, 3236–3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarli, A. The Psycho-Social Malaise of Migrant Private Carers in Italy: A Rampant, but Hidden Health Demand. Acta Biomed. 2014, 85, 62–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon, L. Suicidal and Depressive Symptoms in Filipino Home Care Workers in Israel. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 2012, 27, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, H.; Palenga-Möllenbeck, E. Care, Gender and Migration: Towards a Theory of Transnational Domestic Work Migration in Europe. J. Contemp. Eur. Stud. 2011, 19, 349–364. [Google Scholar]

- Casanova, G.; Tur-Sinai, A.; Lamura, G. Innovating Long-Term Care Provision in Mediterranean Welfare States: A Comparison Between Italy and Israel. J. Aging Soc. Policy 2020, 32, 55–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrinzi, F. Beyond “Women’s Work”: Gender, Ethnicity, and the Management of Paid Care Work in Nonprofit Domiciliary Services in Italy. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2019, 17, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.H. Reproducing the National Family: Kinship Claims, Development Discourse and Migrant Caregivers in Palestine/Israel. Fem. Theory 2019, 20, 247–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srakar, A.; Hrast, M.F.; Hlebec, V.; Majcen, B. Social Exclusion, Welfare Regime and Unmet Long-Term Care Need: Evidence from SHARE. Ageing Eur. Support. Polic. Incl. Soc. 2015, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Green, O.; Ayalon, L. Violations of Workers’ Rights and Exposure to Work-Related Abuse of Live-in Migrant and Live-out Local Home Care Workers—A Preliminary Study: Implications for Health Policy and Practice. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2018, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, S.; Corsonello, A.; Chiatti, C.; Fabbietti, P.; Salerno, G.; De Bonis, E.; Corica, F.; Lattanzio, F. Migrant Care Workers and Rehospitalization among Older Patients Discharged from Acute Care Hospitals. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2015, 15, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, P. Relations of Care: The Contexts for Immigrant Care Workers in Northern Italy. Antropol. Work Rev. 2015, 36, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccagni, P. Searching for Well-Being in Care Work Migration: Constructions, Practices and Displacements among Immigrant Women in Italy. Soc. Polit. 2016, 23, 284–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordini, M.; Ranci, C. Legitimising the Care Market: The Social Recognition of Migrant Care Workers in Italy. J. Soc. Policy 2017, 46, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassar, L.; Ferrero, L.; Portis, L. ‘More like a Daughter than an Employee’: The Kinning Process between Migrant Care Workers, Elderly Care Receivers and Their Extended Families. Identities 2017, 24, 524–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scrinzi, F. Caring for the Elderly in the Family or in the Nation? Gender, Women and Migrant Care Labour in the Lega Nord. West Eur. Polit. 2017, 40, 869–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccagni, P. At Home in Home Care? Contents and Boundaries of the ‘Domestic’ among Immigrant Live-in Workers in Italy. Hous. Stud. 2018, 33, 813–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonatti, V.; Muniandy, P. Defiant Aspirations: Migrant Women’s Struggles for Stability and Upward Mobility in Naples and Kuala Lumpur. Migr. Stud. 2018, 8, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherubini, D.; Geymonat, G.G.; Marchetti, S. Global Rights and Local Struggles: The Case of the ILO Convention N.189 on Domestic Work. Partecip. Confl. 2018, 11, 717–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolescu, G. From Border Fetishism to Tactical Socialism. East. Cent. Eur. 2018, 45, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solari, C.D. Transnational Moral Economies: The Value of Monetary and Social Remittances in Transnational Families. Curr. Sociol. 2019, 67, 760–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranci, C.; Arlotti, M. Resistance to Change. The Problem of High Non-Take up in Implementing Policy Innovations in the Italian Long-Term Care System. Policy Soc. 2019, 38, 572–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolescu, G. Keeping the Elderly Alive Global: Entanglements and Embodied Practices in Long-Term Care in Southeast Italy. Anthropol. Aging 2019, 40, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vianello, F.A.; Finotelli, C.; Brey, E. A Slow Ride towards Permanent Residency: Legal Transitions and the Working Trajectories of Ukrainian Migrants in Italy and Spain. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalon, L.; Halevy-Levin, S.; Ben-Yizhak, Z.; Friedman, G. Personal Home Care Workers’ Role in Hospital: A Qualitative Study. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2015, 20, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, O.; Ayalon, L. Whose Right Is It Anyway? Familiarity with Workers’ Rights among Older Adults, Family Caregivers, and Migrant Live-in Home Care Workers: Implications for Policy and Practice. Educ. Gerontol. 2015, 41, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazuz, K. Elderly Care between Global and Local Services: The Use of Somatic Care Practices. BMJ Case Rep. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalon, L.; Roziner, I. Satisfaction with the Relationship from the Perspectives of Family Caregivers, Older Adults and Their Home Care Workers. Aging Ment. Health 2016, 20, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronstein, J. A Transitional Approach to the Study of the Information Behavior of Domestic Migrant Workers: A Narrative Inquiry. J. Doc. 2019, 75, 314–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Golander, H.; Iecovich, E.; Jensen, B. Social Engagement Care for Frail Older Persons: Desire for It and Provision by Live-In Migrant Caregivers. J. Gerontol. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2019, 74, 1062–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, O.; Babis, D. Towards Professionalism through Social Networks: Constructing an Occupational Community via Facebook Usage by Temporary Migrant Workers from the Philippines. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2019, 22, 1230–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinan-Altman, S.; Ayalon, L. Perceived Control among Migrant Live-in and Local Live-out Home Care Workers in Israel. Aging Ment. Health 2019, 23, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teshuva, K.; Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Iecovich, E.; Golander, H. Like One of the Family? Understanding Relationships between Migrant Live-in Care Workers and Older Care Recipients in Israel. Ageing Soc. 2019, 39, 1387–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holler, R. Material, Stigmatic, and Agentic Dimensions in the Experience of Claiming Disability Benefits: The Israeli Case. Soc. Policy Adm. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic analysis. In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological; Cooper, H.E., Camic, P.M., Long, D.L., Panter, A.T., Rindskopf, D.E., Sher, K.J., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Volume 2, pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, F. Reflections on the Process of Conducting Secondary Analysis of Qualitative Data Concerning Informed Choice for Young People with a Disability in Transition. Forum Qual. Soc. Res. 2015, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Roit, B.; Le Bihan, B. Similar and Yet So Different: Cash-for-Care in Six European Countries’ Long-Term Care Policies. Milbank Q. 2010, 88, 286–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addati, L.; Cattaneo, U.; Esquivel, V.; Valarino, I. Care Work and Care Jobs for the Future of Decent Work; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Da Roit, B.; Van Bochove, M. Migrant Care Work Going Dutch? The Emergence of a Live†in Migrant Care Market and the Restructuring of the Dutch Long†term Care System. Soc. Policy Adm. 2017, 51, 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkins, B.; Lindgren, D.; Suravoranon, T. Risks and Rewards: Outcomes of Labour Migration in South-East Asia; ILO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2017; ISBN 92-2-131411-1. [Google Scholar]

- Jayaweera, H.; Anderson, B. Migrant Workers and Vulnerable Employment: A Review of Existing Data. Report for TUC Commission on Vulnerable Employment; University of Oxford’s Centre on Migration, Policy and Society (COMPAS): Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Behind Closed Doors: Protecting and Promoting the Human Rights of Migrant Domestic Workers in an Irregular Situation; Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR): New York, NY, USA; Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Tunon, M.; Harkins, B. Addressing Irregular Migration and Violations of Migrant Worker’s Rights. In Safeguarding the Rights of Asian Migrant Workers from Home to the Workplace; Asian Development Bank Institute, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and International Labour Organization: Toyko, Japan; Bankok, Tailand; Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Grimwade, M.; Neumann, P. Migration Policy and Practice in Thailand; United Nations Thematic Working Group on Migration in Thailand: Bangkok, Thailand, 2019; pp. 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Takahata, S. Can Certified Care Workers Become Long-term Settlers? Case Study of 49 Filipinos under the Japan–Philippines Economic Partnership Agreement. Int. J. Jpn. Sociol. 2016, 25, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niki, I. Policymaking Process for Foreign Care Workers in Contemporary Japan: Changes and Continuations. New Sociol. J. Crit. Prax. 2020, 1, 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa, R. Intersectionality and Differentiated Citizenship: Migrant Care Workers in Japan. Asia Pac. J. Soc. Work Dev. 2017, 27, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, R. Migrant Care Workers and Care-Migration Policies: A Comparison between Italy and Japan. Asia Eur. J. 2019, 17, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y. Workers by Any Other Name: Comparing Co-Ethnics and ‘Interns’ as Labour Migrants to Japan. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2019, 45, 1496–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B. Worker, Helper, Auntie, Maid? Working Conditions and Attitudes Experienced by Migrant Domestic Workers in Thailand and Malaysia; ILO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2016; ISBN 92-2-131348-4. [Google Scholar]

- Horn, V.; Schweppe, C.; Böcker, A.; Bruquetas-Callejo, M. Live-in Migrant Care Worker Arrangements in Germany and the Netherlands: Motivations and Justifications in Family Decision-Making. Int. J. Ageing Later Life 2019, 13, 83–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leghtas, I. Hidden Away: Abuses against Migrant Domestic Workers in the UK; Human Rights Watch: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Labour Inspection: Women Migrant Workers in ASEAN; UN Women and the International Labour Organization: Bangkok, Thailand, 2015; pp. 1–7.

- Bruquetas Callejo, M. Long-Term Care Crisis in The Netherlands and Migration of Live-in Care Worker. Int. Migr. 2020, 58, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Garms-Homolová, V.; Bentwich, M. Migrant Home Attendants: Regulation and Practice in 7 Countries. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, e30–e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.-F. Live-in Migrant Care Workers in Taiwan: The Debate on the Household Service Act. Asian Pac. Migr. J. 2014, 23, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordolan, L.; Lalani, M. Care and Immigration: Migrant Care Workers in Private Households; Kalayaan: London, UK, 2009; pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lalani, M. Ending the Abuse: Policies that Work to Protect Migrant Domestic Workers; Kalayaan: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Christian, M.; Namaganda, A. Transnational Intersectionality and Domestic Work: The Production of Ugandan Intersectional Racialized and Gendered Domestic Worker Regimes. Int. Sociol. 2018, 33, 315–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhde, Z. Social Bias within the Institution of Hired Domestic Care: Global Interactions and Migration. Civ.-Rev. Ciênc. Soc. 2016, 16, 682–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, C. The Enduring Vulnerability of Migrant Domestic Workers in Europe. Int. Comp. Law Q. 2013, 62, 599–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, V. Migrant Domestic Workers, Vulnerability and the Law: Immigration and Employment Laws in Cyprus and Spain. Investig. Fem. 2016, 7, 149–168. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, L.-F. Creating a Gendered-Racialized Care Labor Market: Migrant Labor Policy and the Transformation of Care Work in Taiwan. In Gender, Care and Migration in East Asia; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 139–156. [Google Scholar]

- Asis, E.; Carandang, R.R. The Plight of Migrant Care Workers in Japan: A Qualitative Study of Their Stressors on Caregiving. J. Migr. Health 2020, 1, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Out of Sight: Migrant Women Exploited in Domestic Work; European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights: Vienna, Austria, 2017.

- Lutz, H. Care Migration: The Connectivity between Care Chains, Care Circulation and Transnational Social Inequality. Curr. Sociol. 2018, 66, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behtoui, A.; Boréus, K.; Neergaard, A.; Yazdanpanah, S. Why Are Care Workers from the Global South Disadvantaged? Inequality and Discrimination in Swedish Elderly Care Work. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2020, 43, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, J. Making Migrant Domestic Work Visible: The Rights Based Approach to Migration and the ‘Challenges of Social Reproduction’. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 2010, 17, 840–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachetti, F.C.; Abrahamson, P.; Babovic, M.; Bahurmoz, A.; Biondi, A.; Quamruzzaman, A.; Thomas, M. Women in Global Care Chains: The Need to Tackle Intersecting Inequalities in G20 Countries. Think 20 (T20). 2020. Available online: https://www.g20-insights.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/women-in-global-care-chains-the-need-to-tackle-intersecting-inequalities-in-g20-countries-1606211465.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Ghaddar, A.; Khandaqji, S.; Ghattas, J. Justifying Abuse of Women Migrant Domestic Workers in Lebanon: The Opinion of Recruitment Agencies. Gac. Sanit. 2020, 34, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez Orozco, A. Global Care Chains: Toward a Rights-Based Global Care Regime? United Nations International Research and Training Institute for the Advancement of Women: Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, 2010; ISBN 92-1-054576-1. [Google Scholar]

- Rogalewski, A.; Florek, K. The Future of Live-in Care Work in Europe: Report on the EESC Country Visits to the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy and Poland Following up on the EESC Opinion on “The Rights of Live-in Care Workers”; European Economic and Social Committee: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Israel, H.; Feller, O. No State for Love: Violations of the Right to Family of Migrant Workers in Israel; Kav LaOved and The Association for Civil Rights in Israel (ACRI): Tel Aviv, Israel, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Israel, H. Revisiting CEDAW’s Recommendations: Has Anything Changed for Migrant Workers in Israel in the Last Two Years? Kav LaOved: Tel Aviv, Israel, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Labour Inspection and Other Compliance Mechanisms in the Domestic Work Sector Introductory Guide; International Labour Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

| Study | Design | Field of Journal | Country Focus | Sample | Study Aim |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ayalon et al., 2015 [63] | Qualitative | Health Services Research and Policy | Israel | 17 CRs 1, 16 family members 2, 20 MCWs 3 and 20 nurses | Understand the role of live-in MCWs in providing social care to patients in hospitals |

| Fusco et al., 2015 [49] | Quantitative | Geriatrics and Gerontology | Italy | 506 CRs | Determine the impact of how being assisted by MCWs affects rehospitalization rates |

| Green and Ayalon, 2015 [64] | Quantitative | Gerontology | Israel | 338 MCWs, 224 CRs, and 442 family members | Examine the extent to which people in need of support, family members, and MCWs are familiar with the rights of live-in MCWs |

| Mazuz, 2015 [65] | Qualitative | Global Health | Israel | 1 triad (CR, family member, and MCW) | To analyze the use of somatic care practices by live-in MCWs |

| Meyer, 2015 [50] | Qualitative | Anthropology | Italy | MCWs—does not specify how many | Examine how MCWs negotiate their work lives |

| Ayalon and Roziner, 2016 [66] | Quantitative | Ageing Mental Health | Israel | 23 triads (MCWs, CRs and family members) | Evaluate the satisfaction of relationships between people in need of support, their family members, and home care workers |

| Barbabella et al., 2016 [29] | Quantitative | Gerontology | Italy | 438 CRs–primary family caregiver dyads | Investigate the socio-economic predictors of hiring MCWs |

| Boccagni, 2016 [51] | Qualitative | Social Politics | Italy | 30 MCWs | To explore women MCWs mediation between different forms of well-being and to understand how these dimensions are understood, experienced and/or displaced while abroad |

| Green and Ayalon, 2016 [39] | Quantitative | Interpersonal Violence | Israel | 187 MCWs | Explore help-seeking behaviours among MCWs who have experienced work-related abuse |

| Kemp and Kfir, 2016 [23] | Qualitative | Social Problems | Israel | 15 NGO 4 staff members | Explain how civil society actors have mediated between the bio-political contradiction that MCWs are wanted workers but as unwanted mothers |

| Baldassar, Ferrero and Portis, 2017 [53] | Qualitative | Global Studies in Culture and Power | Italy | 8 MCWs and 10 CRs and family members | Explain how kinning processes between MCWs and people in need of support develops |

| Cordini and Ranci, 2017 [52] | Qualitative | Social Policy | Italy | Content analysis of the public discourse in newspapers | Provide evidence on how market dynamics have allowed governments to shift the responsibility of providing home care to MCWs |

| Palumbo, 2017 [37] | Qualitative | Immigrant and Refugee studies | Italy | 3 MCWs, 4 judicial and law enforcement authorities, 3 lawyers, 4 policymakers, 4 government representatives, 5 representatives of NGOs, 3 social workers, 2 trade unionists and 2 experts | Analysis of why exploitation in the domestic work sector is rarely acknowledged or addressed with polices around trafficking and exploitation |

| Rugolotto, Laroto, and van der Geest, 2017 [38] | Qualitative | Migration, Health and Social Care | Italy | 20 MCWs, and 5 family members | Describe how migration affects the care being provided to people in need of support |

| Scrinzi, 2017 [54] | Qualitative | Western European Politics | Italy | 20 party members of a political party | Examine the relationship between anti-immigration politics and the racialized and gendered division of care work |

| Boccagni, 2018 [55] | Qualitative | Housing Studies | Italy | 165 MCWs | Analyze how live-in MCWs feel in their everyday lives abroad |

| Bonatti and Muniandy, 2018 [56] | Qualitative | Migration Studies | Italy and Malaysia | 16 MCWs in Italy and 15 MCWs in Malaysia | Explain how migrant women develop and pursue their aspirations by examining the institutional limitations they face |

| Cherubini, Geymonat, and Marchetti, 2018 [57] | Qualitative | Participation and Conflict | Italy, Colombia, the Philippines, and Taiwan | Policy analysis of laws | Show how the ILO Domestic Workers Convention (No. 189) has been incorporated or resisted in local contexts |

| Green and Ayalon, 2018 [48] | Quantitative | Health Policy Research | Israel | 338 MCWs and 185 Israeli care workers | Assess the working conditions and prevalence of abuse and exploitation faced by live-in MCWs and live-out local care workers |

| Nicolescu, 2018 [58] | Qualitative | East Central Europe | Italy | 34 MCWs | Discuss how migrating to work in the care sectors is a transborder continuity of autonomy and employment practices that survive socialism |

| Bronstein, 2019 [67] | Qualitative | Documentation | Israel | 20 MCWs | Examine the life stories of MCWs by analyzing different aspects of information behaviour that has emerged from their narratives through a transnational perspective |

| Brown, 2019 [45] | Qualitative | Feminist theory | Israel/Palestine | 15 employers of MCWs 5 | Examine the politics of the MCW–employer relationship as it unfolds within the Jewish-Israeli home |

| Cohen-Mansfield, 2019 [68] | Mixed methods—qualitative and qualitative | Gerontology | Israel | 111 family members, 61 CRs, and 98 MCWs | Describe the social engagement care provided by live-in MCWs for frail older adults in comparison with the wishes of people in need of support and their families’ wishes for this care |

| Golan and Babis, 2019 [69] | Qualitative | Information, Communication and Society | Israel | 800 Facebook posts | Explain how social networking site expressions shape an occupational community of temporary migrant workers |

| Ranci and Arlotti, 2019 [60] | Mixed methods—qualitative and qualitative | Policy and Society | Italy | 60 key informants and INPS 6 data | Show how non-take up rates of health services can be explained by individually situated decisions taken by beneficiaries based on cost-benefit evaluations that are rooted in social attitudes shaped by existing institutional contexts |

| Nicolescu, 2019 [61] | Qualitative | Anthropology and Aging | Italy | 34 MCWS and 24 employers of MCWs | Explore the success of the migrant in the family model and the mechanisms that bond MCWs and people in need of support in a mutual dependency |

| Solari, 2019 [59] | Qualitative | Sociology | Italy | 61 MCWs and 39 adult children whose parent(s) were abroad | Uncover the meanings that MCWs and their non-migrant children assign to monetary and social remittances |

| Shinan-Altman and Ayalon, 2019 [70] | Quantitative | Ageing Mental Health | Israel | 338 MCWs and 185 Israeli care workers | Examine the perceived control among live-in MCWs and live-out local care workers and identify the factors that contribute to this perceived control |

| Scrinzi, 2019 [44] | Qualitative | Immigrant and Refugee Studies | Italy | 10 managers of the social cooperatives | Examine how strategies adopted by managers at social cooperatives challenge dominated gendered constructs of care work |

| Teshuva et al., 2019 [71] | Mixed methods—qualitative and qualitative | Ageing and Society | Israel | 116 MCWs and 73 CRs | Explore the quality and the nature of relationships between live-in MCWs and people in need of support |

| Vianello, Finotelli and Brey, 2019 [62] | Qualitative | Ethnic and Migration Studies | Italy and Spain | 10 MCWs in Italy and 10 MCWs in Spain | Investigate the process of residence permit renewals among migrants |

| Casanova, Tur-Sinai and Lamura, 2020 [34] | Qualitative | Ageing and Social Policy | Italy and Israel | Long-term care experts—12 in Israel, 27 in Italy | Identify the challenges and responses that have been adopted or should be adopted to improve long- term care provision in Italy and Israel |

| Holler, 2020 [72] | Qualitative | Social Policy and Administration | Israel | 30 CRs | Examine the lived experience of people claiming disability benefits |

| Key Concepts | Italy | Israel |

|---|---|---|

| Macro Level | ||

| Gender Regime | [37,52,53,54,55,59,62] | [45,48,65] |

| Migration Regime | [37,38,52,54,56,61,62] | [23,34,39,64,67,69] |

| Care Regime | [29,34,37,38,44,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,58,60,61,62] | [34,39,45,48,65,68,69,72] |

| Employment Regime | [37,50,57,58,61,62] | [39,48,64,65,69] |

| Micro Level | ||

| Gender | [37,44,50,51,53,55,59] | [23,39,45,48,65,68] |

| Power/Class Asymmetry | [37,44,50,51,55,59,61] | [23,45,48,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71] |

| Culture, Ethnicity and Religion | [37,38,44,50,55,56] | [39,45,48,64,65,67,68,71] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fisher, O. The Impact of Micro and Macro Level Factors on the Working and Living Conditions of Migrant Care Workers in Italy and Israel—A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020420

Fisher O. The Impact of Micro and Macro Level Factors on the Working and Living Conditions of Migrant Care Workers in Italy and Israel—A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(2):420. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020420

Chicago/Turabian StyleFisher, Oliver. 2021. "The Impact of Micro and Macro Level Factors on the Working and Living Conditions of Migrant Care Workers in Italy and Israel—A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 2: 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020420

APA StyleFisher, O. (2021). The Impact of Micro and Macro Level Factors on the Working and Living Conditions of Migrant Care Workers in Italy and Israel—A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020420