The Sustainability of Waste Management Models in Circular Economies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. State of the Art

2.1. The Circular Economy as a Model to Achieve Sustainable Development

2.2. Waste Management

2.3. Climate Change and Waste Management

2.4. Extended Producer Responsibility

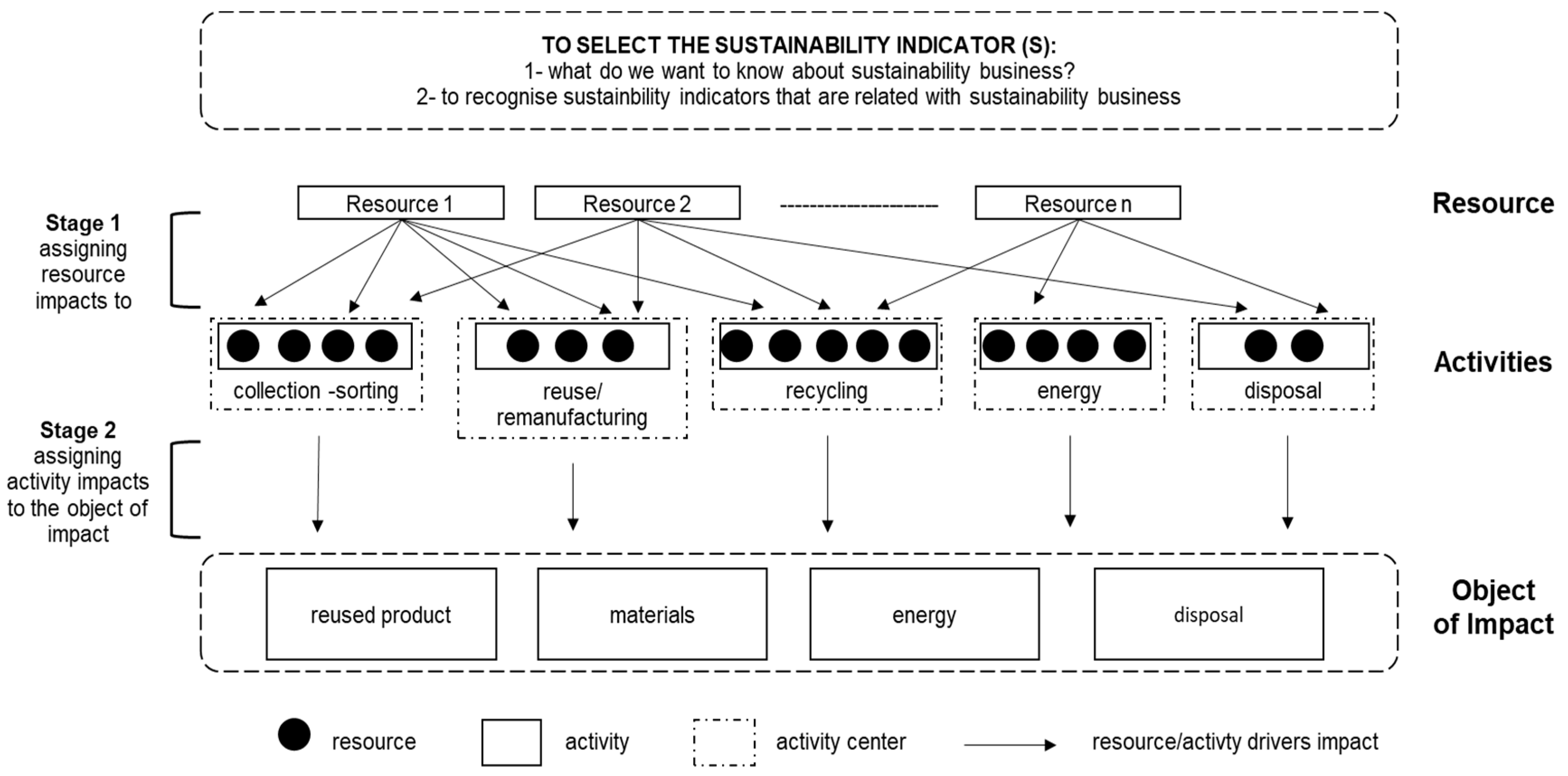

3. Modelization of Sustainable Management of CPR: Activity Based Sustainability Model

- Activities at company level are the activities carried out by the CPR so that the producers comply with the current legislation in force.

- Activities at the product level are activities related to the reuse and recycling of waste: collection, sorting, preparation for reuse, recycling, to name a few.

4. Empirical Implementation of Sustainable Management of a CPR from the Perspective of Climate Change

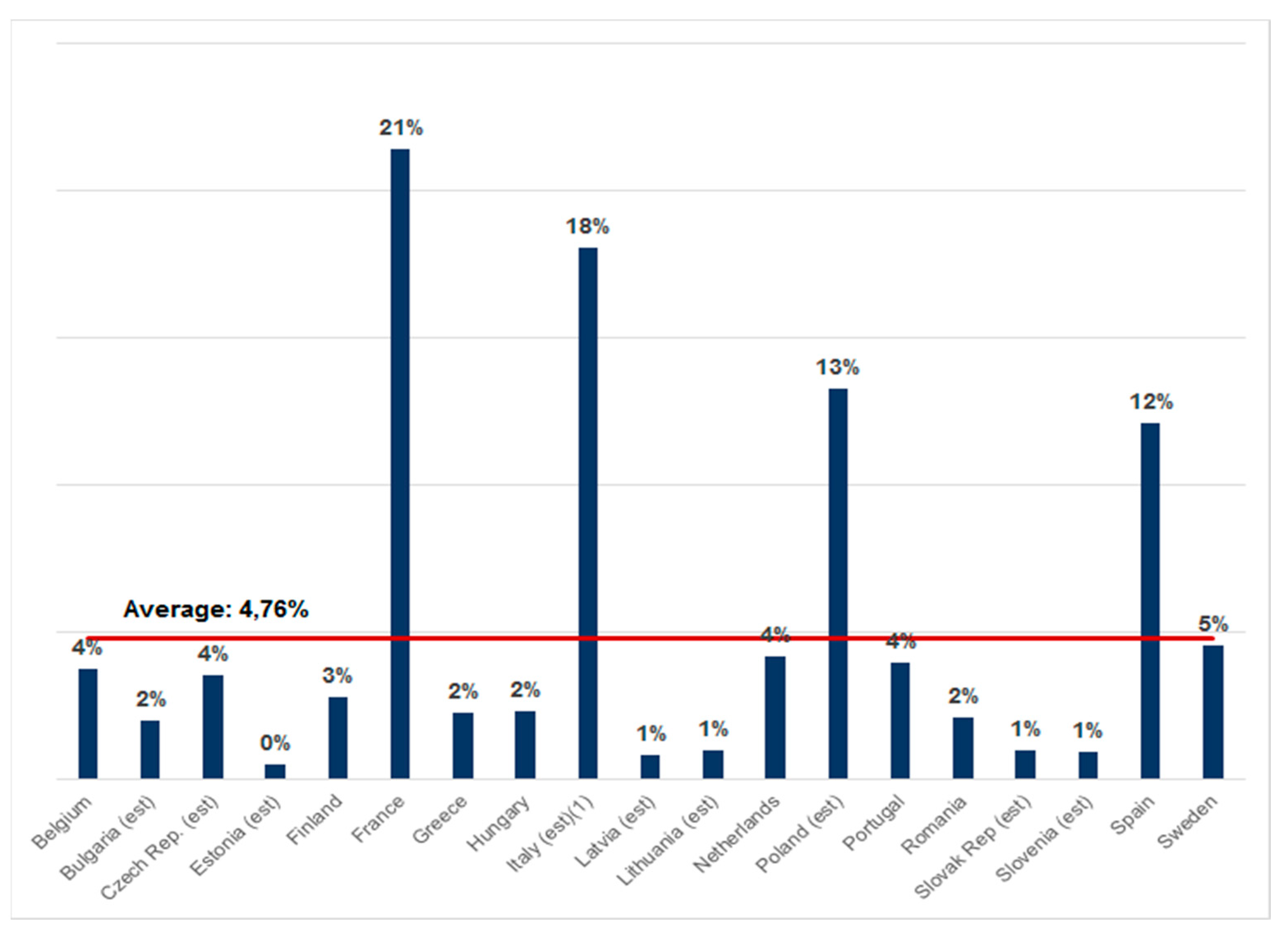

4.1. Climate Impact of the Management of Used Tires in the European Union

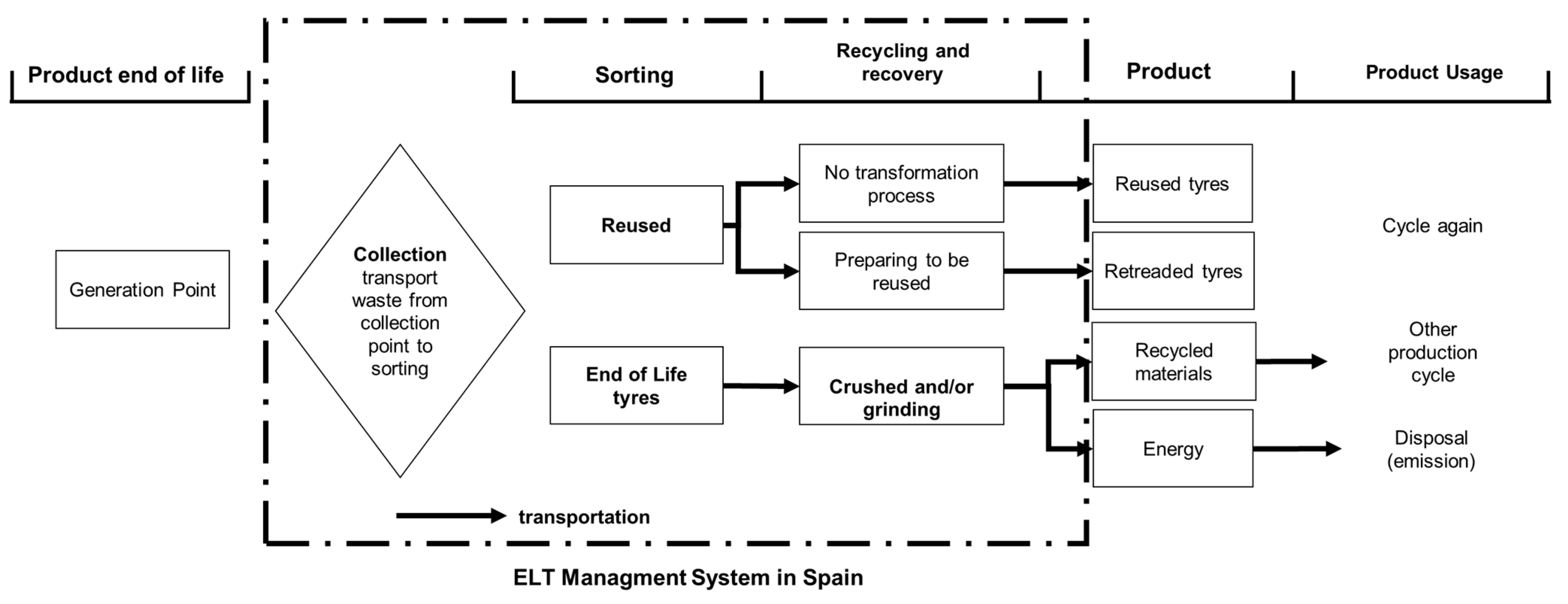

- Collection and sorting: consisting of the UT collection from the generation points to the collection and sorting centers (CSC), where reusable used tires and tires beyond their working lifetime (ELT) are separated.

- Recycling and recovery: ELT that cannot be reused are derived either from the recycling process for the separation of different materials for their material recovery (grinding process) or energy recovery (cement kilns, energy, energy generation).

- Transportation: this activity involves the transfer of the ELT from the CSC to the different recovery facilities.

4.2. Implementation of SBA from Climate Change Perspective: Three-Stages Analysis

- Activities at company level are the activities that support the management of ELT.

- ○

- ELT management: these are the activities carried out by CPR for compliance with Law 22/2011 affecting tire manufacturers.

- Batch level activities are the activities that are performed each time a batch of products is processed:

- ○

- Collection–sorting;

- ○

- Recycling–recovery;

- ○

- Transportation.

4.2.1. Preliminary Stage: To Identify Sustainability Indicator8a

- Scope 1: Direct emissions occur from sources that are owned or controlled by the company.

- Scope 2: These are indirect emissions generated by electricity acquired and consumed by the organization.

- Scope 3: These are other indirect emissions that are a consequence of the company’s activities but occur in sources that are not owned or controlled by the company.

- Scope: 1

- ○

- Emissions from mobile combustion: derived from fuel consumption by vehicles owned by the company.

- ○

- Fugitive emissions generated by the use of air conditioners.

- Scope 2:

- ○

- Indirect emissions from the importation of electrical energy from electricity suppliers and for heat pump heating supplied by the building manager where companies headquarters are located.

- Scope 3:

- ○

- Professional journeys: these are the emissions generated by the trips that employees must make to undertake their professional activities at CPR.

- ○

- Transportation of customers and visitors: these are the emissions emitted by the transportation of visitors and customers who are invited by CPR.

- ○

- End of product life, and it is divided into three sections:

- Collection–sorting: emissions in ELT transport activities from the collection points to the classification centers (CSC). The sorting process involves the separation of ELT for reuse or recycling.

- Recycling and recovery: GHGs generated in the processes of recycling and recovery of the ELT.

- Transportation: GHG emissions caused by the transport of ELT from CSC to recycling centers and/or energy valuation.

- ○

- Employee mobility: these are the emissions that occur in transportation that employees use to go to their jobs from their homes and vice versa.

4.2.2. Stage 1: Assigning Resources Impacts to Activities

- Step 1: Identification of GHG emissions at activity level:

- GHG emissions at company level:

- ELT management: the sum of the emissions of scopes 1 and 2 and the following GHG emissions of scope 3: work trips, events, employee mobility and customer and visitor trips.

- Emissions at the lot level:

- Collection–sorting: totaling 3,783.19 tCO2e, which come from the consumption of fuel in the ELT collection activity and fuel and electricity for classification.

- Recycling–recovery: this activity generates a total of 6,608.82 tCO2e derived mainly from electricity consumption.

- Transport: the emissions generated by this activity are 2,602.19 tCO2e produced by fossil fuel consumption.

- Step 2: Identification of the drivers involved in the activities:

- GHG emissions at company level: the driver is the number of companies involved in the management of ELT. In this case, for the year 2017 SIGNUS managed 50 companies.

- GHG emissions at the lot level: the driver is the tonnes of ELT managed:

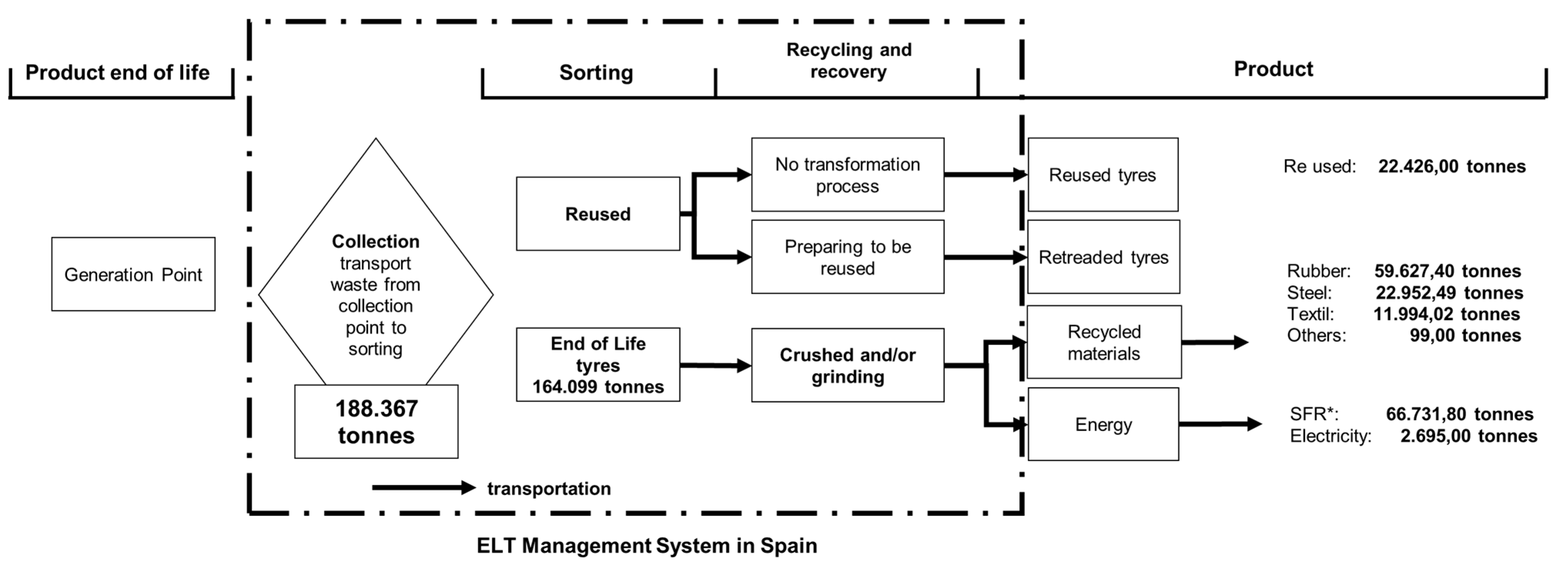

- Collection-sorting: 188,367 tonnes of ELT collected and classified.

- Recycling-recovery: 164,099 tonnes of recycled ELT, 94,673 tonnes to obtain materials to reintroduce them into the system and 69,426 tonnes for energy production.

- Transport: 131,598.52 tonnes transported from the sorting centers to the recycling centers: 127,355.61 tonnes by land transport and 4242.91 by sea transport.

- Step 3: Unit GHG emissions for each activity:

- GHG emissions at company level: GHG emissions by number of companies.

- GHG emissions at the lot level: GHG emissions per ton of ELT managed.

- Step 4: Assignment of GHG emissions for each activity pertaining to the waste management process: reuse, recycling material recovery, recycling energy recovery and disposal.

4.2.3. Stage 2: Assigning Activity Impacts to the Objects of Impact

- Step 1: Identification of impact object:

- Reused tire.

- Recycling material recovery (grinding process). The materials obtained are: rubber, steel, textile and others;

- Recycling energy recovery (crushing process). Combustion or generation of electrical energy.

- Step 2: Identification of the drivers of the impact objects. For any of these, tonnes of ELT are used.

- Step 3: Unit GHG emissions for each impact object: GHG emissions per ton of ELT.

- Step 4: Assignment of GHG emissions to the impact object.

5. Results and Discussion

- ELT Collection–sorting activity: it consumes 1,115,304.63 litres of diesel for the transport of ELT from the collection points to the classification centers. The centers consume a total of 641,663.73 kWh of electricity.

- Recycling–recovery activity: its electricity consumption amounted to 18,359,041.05 kWh for obtaining granules and 314,764.25 kWh for crushing. Only 9.59% of the electricity consumed to obtain granules comes from renewable resources.

- Transport: There are no consumption data derived from the kilometers travelled, but of the type of resources used, diesel or gasoline, both non-renewable resources are known.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Blomsma, F.; Brennan, G. The Emergence of Circular Economy: A New FramingAround Prolonging Resource Productivity. J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, e603–e614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMF. Towards a Circular Economy: Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition Accessed. 2015. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/TCE_Ellen-MacArthur-Foundation_9-Dec-2015.pdf (accessed on 30 June 2018).

- Bocken, N.M.P.; de Pauw, I.; Bakker, C.; van der Grinten, B. Product design and business model strategies for a circular economy. J. Ind. Prod. Eng. 2016, 33, 308e320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sauvé, S.; Bernard, S.; Sloan, P. Environmental sciences, sustainable development and circular economy: Alternative concepts for trans-disciplinary research. Environ. Dev. 2016, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy: A new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, e757–e768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Korhonen, J.; Honkasalo, A.; Seppälä, J. Circular Economy: The Concept and its limitations. Ecol. Econ. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Vladimirova, D.; Evans, S. Sustainable business model innovation: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, e401–e416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, M.P.P.; McAloone, T.C.; Pigosso, D.C.A. Business model innovation of circular economy and sustainability: A review of approaches. J. Clean. Prod. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassarre, B.; Schepers, M.; Bocken, N.; Cuppen, E.; Korevaar, G.; Calabretta, G. Industrial Symbiosis: Towards a design process for eco-industrial clusters by integrating Circular Economy and Industrial Ecology perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraga, G.; Huysveld, S.; Mathieux, F.; Blengini, G.A.; Alaerts, L.; Van Acker, K.; de Meester, S.; Dewulf, J. Circular economy indicators: What do they measure? Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Circular Economy in Europe-Developing the Knowledge Base; European Environment Agency/Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; ISBN 978-92-9213-719-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, A.; Marthino, G. Waste hierarchy index for circular economy in waste management. Waste Manag. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, Y.; Fu, J.; Sarkis, J.; Xue, B. Towards a national circular economy indicator system in China: An evaluation and critical analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 23, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elia, V.; Gnoni, M.G.; Tornese, F. Measuring circular economy strategies through index methods: A critical analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 2741–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.; Tse, T.; Soufani, K. Introducing a Circular Economy: New Thinking with New Managerial and Policy Implications. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2018, 60, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkinson, P.; Zils, M.; Hawkins, P.; Roper, S. Managing a Complex Global Circular Economy Business Model: Opportunities and Challenges. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2018, 60, 71–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmykova, Y.; Sadagopan, M.; Rosado, L. Circular Economy- from review of theoris and practices to development of implementation tools. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ETRMA. ELT Management Figures 2016. 2018. Available online: http://www.etrma.org/uploads/Modules/Documentsmanager/20180502---2016-elt-data_for-press-release.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2019).

- Wiedmann, T.; Minx, J.C. A definition of carbon footprint. In Ecological Economic Research Trend; Petsan, C.C., Ed.; Nova Science Publisher: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Eiroa, B.; Fernández, E.; Méndez-Martínez, G.; Soto-Oñate, D. Operational principles of circular economy for sustainable development: Linking theory and practice. J. Clean. Prod. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Olalla, A.; Avilés-Palacios, C. Integrating Sustainability in Organisations: An Activity based Sustainability Model. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WCED. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Serageldin, I. Making development sustainable. Financ. Dev. 1993, 30, 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Steffen, W.; Richardson, K.; Rockström, J.; Cornell, S.E.; Fetzer, I.; Bennett, E.; Biggs, R.; Carpenter, S.R.; de Vries, W.; de Wit, C.A.; et al. Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, A.; Lambin, E.; Lenton, T.M.; Folke, C.; Scheffer, M.; Chapin, F.S., III; Nykvist, B.; et al. Planetary boundaries: Exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robért, K.-H.; Broman, G.; Basile, G. Analyzing the concept of planetary boundaries from a strategic sustainability perspective: How does humanity avoid tipping theplanet? Ecol. Soc. 2013, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, J.; Nuur, C.; Feldmann, A.; Birkie, S.E. Circular economy as an essentially contested concept. J. Clean. Prod. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihelcic, J.R.; Crittenden, J.C.; Small, M.J.; Shonnard, D.R.; Hokanson, D.R.; Qiong, Z.H.; Sorby, S.A.; James, V.U.; Sutherland, J.W.; Schnoor, J.L. Sustainability science and engineering: The emergence of anew metadiscipline. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 5314–5324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, M.S. An introductory note of the environmental economics of the circular economy. Sustain. Sci. 2007, 2, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Torres, M.J.; Fernández-Izquierdo, M.A.; Rivera-Lirio, J.M.; Ferrero-Ferrero, I.; Escrig-Olmedo, E.; Gisbert-Navarro, J.V.; Marullo, M.C. An Assessment Tool to Integrate Sustainability Principles into the Global Supply Chain. Sustainatibility 2018, 10, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walmsley, T.G.; Ong, B.H.; Klemeš, J.J.; Tan, R.R.; Varbanov, P.S. Circular Integration of processes, industries, and economies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 107, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EASAC. Indicators for a Circular Circular Economy; European Academies’ Science Advisory Council: Halle, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, J.M. Circular Economy: Theoretical Benchmark or Perpetual Motion Machine? J. Ind. Ecol. 2017, 21, 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauliuk, S. Critical appraisal of the circular economy standard BS 8001:2017 and a dashboard of quantitative system indicators for its implementation in organizations. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 129, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoornweg, D.; Bhada-Tata, P.; Kennedy, C.W. Environment: Waste production must peak this century. Nat. Cell Biol. 2013, 502, 615–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Bank. Global Waste on Pace to Triple by 2100. 2013. Available online: http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2013/10/30/global-waste-on-pace-to-triple (accessed on 30 October 2014).

- Minelgaitė, A.; Liobikienė, G. Waste problem in European Union and its influence on waste management behaviours. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 667, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunner, P.H. Cycles, spirals and linear flows. Waste Manag. Res. 2013, 31, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Das, S.; Lee, S.-H.; Kumar, P.; Kim, K.-H.; Bhattacharya, S.S. Solid waste management: Scope and the challenge of sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 658–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, S.; Debnath, B. Prevalence of Health Hazards Associated with Solid Waste Disposal—A Case Study of Kolkata, India. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2016, 35, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoornweg, D.; Bhada-Tata, P. What a Waste: A Global Review of Solid Waste Management; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, Q.; Deng, F.; Huang, H.; Wan, Q.; Liu, M.; Wei, Y. Mussel-inspired fabrication of functional materials and their environmental applications: Progress and prospects. Appl. Mater. Today 2017, 7, 222–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Zhao, J.; Liu, M.; Chen, J.; Zhu, X.; Wu, T.; Tian, J.; Wen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wei, Y. Preparation of polyethylene polyamine@tannic acid encapsulated MgAl-layered double hydroxide for the efficient removal of copper (II) ions from aqueous solution. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2018, 82, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, H.; Gan, D.; Guo, L.; Liu, M.; Chen, J.; Deng, F.; Zhou, N.; Zhang, X.; Wei, Y. A facile strategy for preparation of magnetic graphene oxide composites and their potential for environmental adsorption. Ceram. Int. 2018, 44, 18571–18577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN). Sustainable Development Goals—17 Goals to Transform Our World. 2016. Available online: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 8 July 2019).

- Cecere, G.; Mancinelli, S.; Mazzanti, M. Waste prevention and social preferences:the role of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations. Ecol. Econ. 2014, 107, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malinauskaite, J.; Jouhara, H.; Czajczynska, D.; Stanchev, P.; Katsou, E.; Rostkowski, P.; Thorne, R.J.; Colón, J.; Ponsá, S.; Mansour, S.; et al. Municipal solid waste management and waste-to-energy in the context of a circular economy and energy recycling in Europe. Energy 2017, 141, 2013–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ewijk, S.; Stegemann, J. Limitations of the waste hierarchy for achieving absolute reductions in material throughput. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 132, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Real Academia Española (RAE). Resiliencia. 2019. Available online: http://www.rae.es/ (accessed on 7 July 2019).

- Tong, S.; Ebi, K. Preventing and mitigating health risks of climate change. Environ. Res. 2019, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. The Global Risks Report 2019, 14th ed.; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-1-944835-15-6. [Google Scholar]

- IPBES. Summary for Policymakers of the IPBES Regional Assessemnt Report on Biodiversity and Ecosistem Services for Europe and Central Asia; IPBES: Bonn, Germany, 2018; ISBN 978-3-947851-03-4. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Global Warming of 1.5 °C. 2018. Available online: http://report.ipcc.ch/sr15/pdf/sr15_spm_final.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2019).

- NASA. 2019. Available online: https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/carbon-dioxide/ (accessed on 3 July 2019).

- Yang, C.H.; Lee, K.C.; Chen, H.C. Incorporating carbon footprint with activity based costing constraints into sustainable publica transport infrastructure project decisions. J. Clean. Prod. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, J.; Chong, W.K.O. The causes of the municipal solid waste and the green house gas emissions from the waste sector in the United States. Waste Manag. 2016, 56, e593–e599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Directive 2008/98/CE on Waste and Repealing Certain Directives (European Parliament and Council). 2008. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02008L0098-20180705&from=EN (accessed on 7 July 2019).

- OECD. Extended Producer Responsibility: A Guidance Manual for Governments; OECD: Paris, France, 2001; 164p. [Google Scholar]

- Lindhqvist, T.; Lidgren, K. Modeller för Förlängt producentansvar [Model for extended producer responsibility]. Ministry of the Environment, Från vaggan till graven–sex studier av varors miljöpåverkan. 1990, pp. 7–44. Available online: https://portal.research.lu.se/portal/en/publications/extended-producer-responsibility-in-cleaner-production-policy-principle-to-promote-environmental-improvements-of-product-systems(e43c538b-edb3-4912-9f7a-0b241e84262f).html (accessed on 15 July 2019).

- Lifset, R.J. Take it back: Extended producer responsibility as a form of incentive-based environmental policy. J. Resour. Manag. Technol. 1993, 21, 163–175. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, D.W.; Turner, R.K. Market-based approaches to solid waste management. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 1993, 8, 63–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickle, G. Extending the boundaries: An assessment of the integration of extended producer responsibility within corporate social responsibility. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 112–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, L.; Atasu, A.; Ergun, Ö.; Toktay, L.B. Design Incentives Under Collective Extended Producer Responsibility: A Network Perspective. Manag. Sci. 2018, 64, 5083–5104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Calvo, E.; Izquierdo, R.; López, P.; Mattera, M. Economía Circular versus Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible: Análisis de la responsabilidad del productor en el caso de los neumáticos fuera de uso. In Proceedings of the 14º Congreso Nacional del Medio Ambiente, Madrid, Spain, 26 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Maas, K.; Schaltegger, S.; Crutzen, N. Integrating corporate sustainability assessment, management accounting, control, and reporting. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 36, 237–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morioka, S.N.; De Carvalho, M.M. A systematic literature review towards a conceptual framework for integrating sustainability performance into business. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 136, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MITECO. Factores de Emisión. Registro de Huella de Carbono, Compensación y Proyectos de Absorción de Dióxido de Carbono. 2018. Available online: https://www.miteco.gob.es/es/cambio-climatico/temas/mitigacion-politicas-y-medidas/factoresemision_tcm30-479095.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2019).

- SIGNUS. Memoria Anual. 2017. Available online: https://www.signus.es/memoria2017/ (accessed on 28 May 2020).

- Navío, C. ¿Porqué es Importante Registrar la Huella de Carbono? 2020. Available online: https://blog.signus.es/por-que-es-importante-registrar-la-huella-de-carbono/ (accessed on 28 May 2020).

- SIGNUS. Memoria Anual. 2016. Available online: https://www.signus.es/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/signus_memoria_2016.pdf (accessed on 28 May 2020).

- World Business Council for Sustainable Development and World Resources Institute. 2004. ISBN 1-56973-568-9. Available online: https://ghgprotocol.org/sites/default/files/standards/ghg-protocol-revised.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2019).

- UK Government GHG Conversion Factor for Company Reporting. 2020. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/greenhouse-gas-reporting-conversion-factors-2020 (accessed on 28 March 2021).

| SCOPE | Sources | Resource/Units | Consumption ** | EF * (kg CO2e/u) | GEI (kg CO2e) (a) | GEI (t CO2e) |

| SCOPE 1 | Corporate vehicles | liters | 9411.76 | 2.38 | 22,400.00 | 22.4 |

| SCOPE 2 | Electricity | kWh | 16,651.16 | 0.43 | 7160.00 | 7.16 |

| Sources | Resource/Units | Consumption ** | EF *** (t CO2e/u) | GEI (t CO2e) (b) | GEI (t CO2e) | |

| SCOPE 3 | Collection and sorting | tonnes of tires | 22,427.00 | 0.07 | 1567.54 | 13,037.29 |

| Recycling—Recovery | 164,099.00 | 11,469.75 | ||||

| Transportation | ||||||

| TOTAL | 13,066.85 |

| Activity Level | Totals (t CO2e) A | Activity Driver B | Driver Number C | GHG/DRIVER (t CO2e/ton) D = A/C UNRWA | Reutilization | Recycling-Material Valuation | Recycling-Energy Valuation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Driver Number E | GEI (t CO2e) F = D + E | Driver Number G | GEI (t CO2e) H = D*G | Driver Number I | GEI (t CO2e) J = D*I | |||||

| Activities at company level (facility level) | ||||||||||

| Management | 29.56 | number of managers | 50 | 0.59 | 29 | 17.14 | 18 | 10.64 | 9 | 5.32 |

| Activities at the production line level (product-sustaining level) | ||||||||||

| Collection + sorting (reuse preparation) | 1567.54 | tonnes | 186,526.00 | 0.01 | 22,427.00 | 188.47 | 94,673.00 | 795.62 | 69,426.00 | 583.45 |

| Recycling +transportation | 11,469.75 | 164,099.00 | 0.07 | 94,673.00 | 6617.20 | 69,426.00 | 4852.55 | |||

| TOTAL GHG EMISSIONS (t CO2e) | 13,066.85 | 205.62 | (1) 7423.46 | (2) 5441.32 | ||||||

| Removed Recycling Material | Rubber | Steel | Textile | Others | ||||||||

| Recycling Process | Totals (t CO2e) A | Object Driver B | Driver Number C | GHG/DRIVER (t CO2e/ton) D = A/C UNRWA | Driver Number E | GEI (t CO2e) F = D + E | Driver Number G | GEI (t CO2e) H = D*G | Driver Number I | GEI (t CO2e) J = D*I | Driver Number K | GEI (t CO2e) L = D*K |

| Recycling material valuation (1) | 7423.46 | tonnes | 94,673.00 | 0.08 | 59,627.40 | 4770.19 | 22,952.49 | 1836.19 | 11,994.02 | 959.52 | 99.00 | 7928 |

| Removed Recycling Material | Grinding | Electrical Power | ||||||||||

| Recycling Process | Driver Number | GEI (t CO2e) | Driver Number | GEI (t CO2e) | ||||||||

| Recycling energy valuation (2) | 5441.32 | tonnes | 69,426.00 | 0.08 | 66,731.80 | 5355.72 | 2695.00 | 216.29 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Avilés-Palacios, C.; Rodríguez-Olalla, A. The Sustainability of Waste Management Models in Circular Economies. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137105

Avilés-Palacios C, Rodríguez-Olalla A. The Sustainability of Waste Management Models in Circular Economies. Sustainability. 2021; 13(13):7105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137105

Chicago/Turabian StyleAvilés-Palacios, Carmen, and Ana Rodríguez-Olalla. 2021. "The Sustainability of Waste Management Models in Circular Economies" Sustainability 13, no. 13: 7105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137105

APA StyleAvilés-Palacios, C., & Rodríguez-Olalla, A. (2021). The Sustainability of Waste Management Models in Circular Economies. Sustainability, 13(13), 7105. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137105