Stimuli Influencing Engagement, Satisfaction, and Intention to Use Telemedicine Services: An Integrative Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Grounds and Literature Review

The S-O-R Framework in Technology and Telemedicine

3. Hypotheses Development

3.1. Performance Expectancy

3.2. Effort Expectancy

3.3. Facilitating Condition

3.4. Price Value

3.5. Contamination Avoidance

3.6. Functionality

3.7. Information Quality

3.8. Engagement

3.9. Satisfaction

3.10. Mediating Effect of Engagement

3.11. Mediating Effect of Satisfaction

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Instrument Development

4.2. Data Collection and Sample

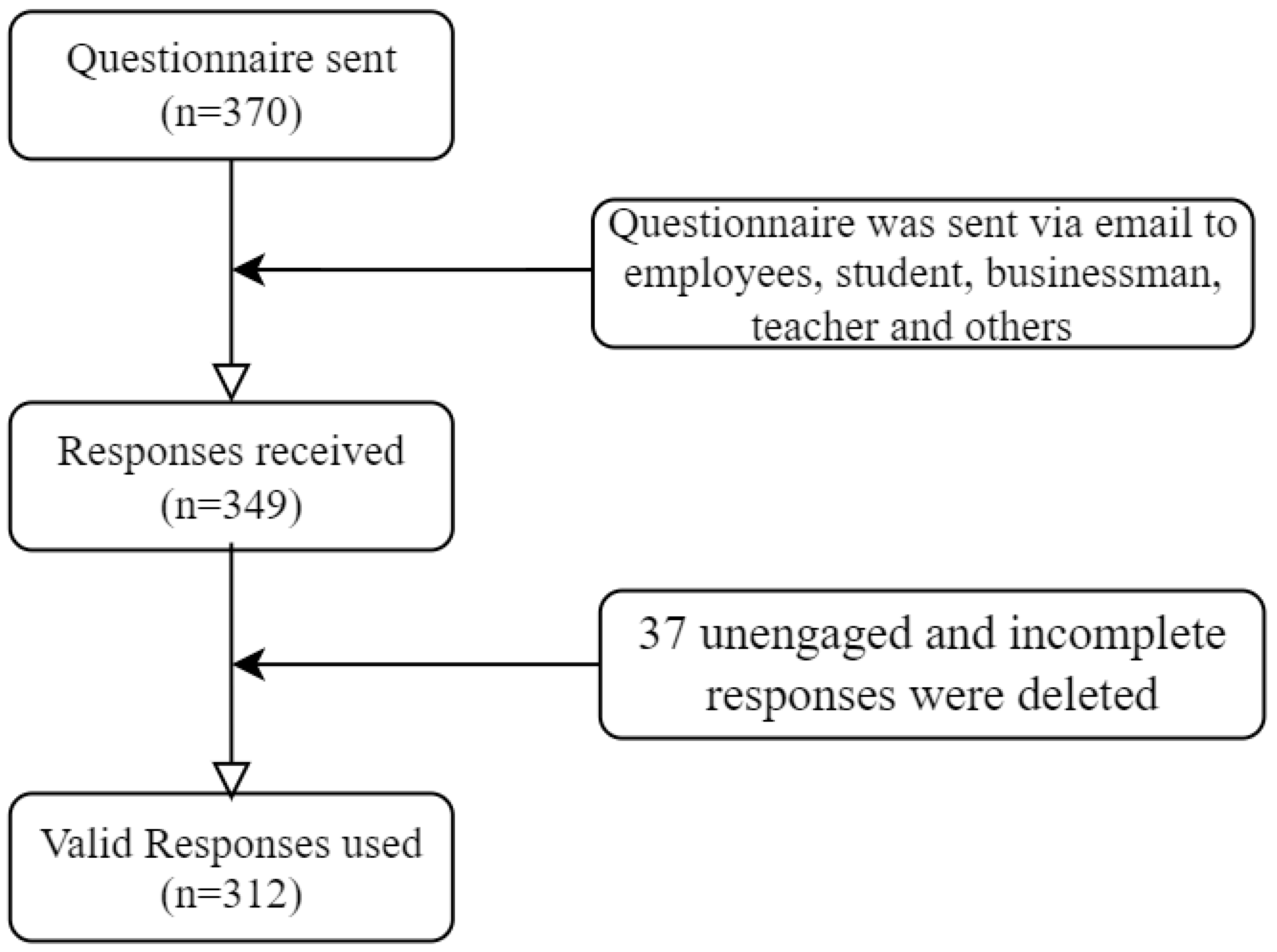

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Participants’ Demographics

5.2. Measurement Model Reliability and Validity

5.3. Method Bias Test

5.4. Model Fit Test

5.5. Structural Model Analysis

6. Discussion

7. Contributions of the Study

7.1. Theoretical Contributions

7.2. Practical Contributions

8. Conclusions, Limitations, and Blueprints for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Constructs (Sources) | Items | Mean | Std. Dev. | Statements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Expectancy (PE) [11,30] | PE2 | 5.92 | 1.190 | Telemedicine would allow me to access healthcare services faster. |

| PE3 | 5.54 | 1.213 | Telemedicine services improve my healthcare efficiency. | |

| PE4 | 5.41 | 1.262 | Telemedicine services increase my capability to manage my health more quickly. | |

| PE5 | 5.62 | 1.178 | Telemedicine would increase my chances of meeting my healthcare needs. | |

| Effort Expectancy (EE) [30] | EE1 | 5.75 | 1.238 | Learning to use telemedicine is effortless for me. |

| EE2 | 5.29 | 1.461 | My interaction with telemedicine is understandable. | |

| EE3 | 5.60 | 1.336 | I find telemedicine platforms easy to use. | |

| EE4 | 5.69 | 1.379 | It is simple to be skillful at using telemedicine services. | |

| Facilitating Conditions (FC) [47] | FC1 | 6.22 | 1.184 | I have the essential resources to use telemedicine. |

| FC2 | 5.89 | 1.276 | I have the necessary knowledge to use telemedicine. | |

| FC3 | 6.07 | 1.052 | The telemedicine service I have used can run on both computer and mobile phone without modifications. | |

| Price Value (PV) [30] | PV1 | 5.00 | 1.583 | The fees or prices for telemedicine services (e.g., doctor’s fees) are reasonable. |

| PV2 | 5.12 | 1.574 | The fees for telemedicine services are affordable. | |

| PV3 | 4.83 | 1.630 | Telemedicine services are good value for the money. | |

| Contamination Avoidance (CA) [11] | CA1 | 5.81 | 1.293 | Telemedicine allows me to avoid a physical visit to the doctor’s office. |

| CA2 | 6.15 | .977 | Telemedicine allows me to avoid physical contact with other patients. | |

| CA3 | 5.96 | 1.140 | Telemedicine allows me to avoid physical contact with the doctor. | |

| CA4 | 6.24 | 1.086 | Telemedicine allows me to avoid touching infected objects (e.g., door handles, chairs) | |

| Functionality (FUNC) [32] | FUNC2 | 5.34 | 1.337 | The sign-up and sign-in processes of the telemedicine service are quick and simple. |

| FUNC3 | 5.12 | 1.403 | The telemedicine service I have used has relevant help buttons/FAQs. | |

| FUNC4 | 5.40 | 1.215 | The menu labels, icons, and instructions of the telemedicine service I have used are straightforward. | |

| FUNC5 | 5.58 | 1.148 | The telemedicine service allows me to navigate or move from one section to another easily. | |

| Information Quality (IQ) [32] | IQ1 | 5.48 | 1.167 | It is effortless to find and understand information on the telemedicine platform. |

| IQ3 | 5.58 | 1.114 | The information available on telemedicine platforms is orderly and easy to read. | |

| IQ4 | 5.49 | 1.137 | Information provided by the telemedicine platform is correct and relevant. | |

| IQ5 | 5.50 | 1.162 | Information provided by the telemedicine platform is timely and updated. | |

| Engagement (ENG) [32] | ENG1 | 5.63 | 1.254 | Telemedicine technology is engaging. |

| ENG2 | 5.51 | 1.237 | Telemedicine technology is interesting. | |

| ENG4 | 5.63 | 1.316 | The telemedicine platform is responsive and holds my attention. | |

| Satisfaction (SAT) [47,67,83] | SAT2 | 5.44 | 1.217 | I am pleased with my experience with telemedicine service. |

| SAT3 | 5.34 | 1.313 | The experience of telemedicine service is exactly what I needed. | |

| SAT4 | 5.44 | 1.276 | I think I did the right thing when I decided to use the telemedicine service. | |

| SAT5 | 5.60 | 1.248 | I like using telemedicine services. | |

| Continuous Usage Intention (CUI) [31,48] | CUI1 | 5.67 | 1.163 | I intend to continue using telemedicine services. |

| CUI4 | 5.68 | 1.149 | I will recommend others to use telemedicine platforms. | |

| CUI5 | 5.39 | 1.291 | I plan to continue to use telemedicine services frequently. |

References

- Sood, S.; Mbarika, V.; Jugoo, S.; Dookhy, R.; Doarn, C.R.; Prakash, N.; Merrell, R.C. Whatis telemedicine? A collection of 104 peer-reviewed perspectives and theoretical underpinnings. Telemed. e-Health 2007, 13, 573–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitten, P.; Sypher, B.D. Evolution of telemedicine from an applied communication perspective in the United States. Telemed. e-Health 2006, 12, 590–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista; Online Doctor Consultations Worldwide. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/dmo/digital-health/ehealth/online-doctor-consultations/worldwide (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Statista; Online Doctor Consultations in Asia. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/dmo/digital-health/ehealth/online-doctor-consultations/asia (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Statista; Online Doctor Consultations in Bangladesh. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/dmo/digital-health/ehealth/online-doctor-consultations/bangladesh (accessed on 26 March 2022).

- Suresh, S.; Nath, L. Challenges in managing telemedicine centers in remote tribal hilly areas of Uttarakhand. Indian J. Commu. Health 2013, 25, 372–380. [Google Scholar]

- Lunney, M.; Thomas, C.; Rabi, D.; Bello, A.K.; Tonelli, M. Video visits using the Zoom for healthcare platform for people receiving maintenance hemodialysis and nephrologists: A feasibility study in Alberta, Canada. Can. J. Kidney Health Dis. 2021, 8, 20543581211008698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utley, L.M.; Manchala, G.S.; Phillips, M.J.; Doshi, C.P.; Szatalowicz, V.L.; Boozer, J.R. Bridging the telemedicine gap among seniors during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Pat. Exp. 2021, 8, 23743735211014036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, J. Effective telemedicine project in Bangladesh: Special focus on diabetes health care delivery in a tertiary care in Bangladesh. Telemat. Inform. 2012, 29, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozzo, R.; Zoccolella, S.; Musio, M.; Barone, R.; Accogli, M.; Logroscino, G. Telemedicine is a useful tool to deliver care to patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis during COVID-19 pandemic: Results from Southern Italy. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Dement. 2020, 21, 542–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudier, P.; Kondrateva, G.; Ammi, C.; Chang, V.; Schiavone, F. Patients’ perceptions of teleconsultation during COVID-19: A cross-national study. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 163, 120510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, I.U.; Sobnath, D.; Nasralla, M.M.; Winnett, M.; Anwar, A.; Asif, W.; Sherazi, H.H.R. Features of mobile apps for people with autism in a post COVID-19 scenario: Current status and recommendations for apps using AI. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Anezi, F.M. Factors influencing decision making for implementing e-health in light of the COVID-19 outbreak in gulf cooperation council countries. Int. Health 2022, 14, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.C.; Thomas, E.; Snoswell, C.L.; Haydon, H.; Mehrotra, A.; Clemensen, J.; Caffery, L.J. Telehealth for global emergencies: Implications for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J. Telemed. Telecare 2020, 26, 309–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, J.; Liu, S.; Zheng, T.; Bi, Y. Physicians’ perspectives of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic in China: Qualitative survey study. JMIR Med. Inform. 2021, 9, e26463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Aca. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, J.K.U.; Von Wangenheim, F. Demystifying AI: What digital transformation leaders can teach you about realistic artificial intelligence. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2019, 61, 110–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triberti, S.; Barello, S. The quest for engaging AmI: Patient engagement and experience design tools to promote effective assisted living. J. Biomed. Inform. 2016, 63, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, G. Examining the determinants and outcomes of mobile app engagement: A longitudinal perspective. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 84, 392–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peters, T.; Işik, Ö.; Tona, O.; Popovič, A. How system quality influences mobile BI use: The mediating role of engagement. Int. J. Inform. Manag. 2016, 36, 773–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. The basic emotional impact of environments. Precep. Mot. Skills 1974, 38, 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Chen, L.; Xiong, M.; Wang, Y. Accelerating AI adoption with responsible AI signals and employee engagement mechanisms in health care. Inform. Syst. Front. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shouk, M.; Soliman, M. The impact of gamification adoption intention on brand awareness and loyalty in tourism: The mediating effect of customer engagement. J. Dest. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omuudu, O.S.; Francis, K.; Changha, G. Linking key antecedents of hotel information management system adoption to innovative work behavior through attitudinal engagement. J. Hospi. Tour. Insights 2022, 5, 274–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-I.; Fu, H.-P.; Mendoza, N.; Liu, T.-Y. Determinants impacting user behavior towards emergency use intentions of m-health services in Taiwan. Healthcare 2021, 9, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahi, S.; Khan, M.M.; Alghizzawi, M. Factors influencing the adoption of telemedicine health services during COVID-19 pandemic crisis: An integrative research model. Enter. Inform. Syst. 2021, 15, 769–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Zhao, L.; Kong, N.; Campy, K.S.; Qu, S.; Wang, S. Factors influencing behavior intentions to telehealth by Chinese elderly: An extended TAM model. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2019, 126, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.M.D.; Alam, M.Z.; Rahman, S.A.; Taghizadeh, S.K. Factors influencing mHealth adoption and its impact on mental well-being during COVID-19 pandemic: A SEM-ANN approach. J. Biomed. Inform. 2021, 116, 103722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herget, N.; Krey, P.S.; Caccamo, M. Mobile Payment Adoption during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Germany. Master’s Thesis, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Quart. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. MIS Quart. 2001, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A.E.; Davenport, T.A.; Wong, T.; Moon, H.W.; Hickie, I.B.; LaMonica, H.M. Evaluating the quality and safety of health-related apps and e-tools: Adapting the mobile app rating scale and developing a quality assurance protocol. Int. Interven. 2021, 24, 100379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wang, A.; Sun, Y. Technological environment, virtual experience, and MOOC continuance: A stimulus–organism–response perspective. Comput. Educ. 2020, 144, 103721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.-H.; Tang, K.-Y. Who captures whom—Pokémon or tourists? A perspective of the stimulus-organism-response model. Int. J. Inform. Manag. 2021, 61, 102312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y. Technology acceptance model and stimulus-organism response for the use intention of consumers in social commerce. Int. J. E-Bus. Res. 2019, 15, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Su, X.; Wang, Y.C. Experiential branded app engagement and brand loyalty: An empirical study in the context of a festival. J. Psychol. Afr. 2020, 30, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreejesh, S.; Sarkar, J.G.; Sarkar, A. Digital healthcare retail: Role of presence in creating patients’ experience. Int. J. Ret. Dist. Manag. 2021, 50, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-W.; Hsub, P.-Y.; Wang, Y.; Chang, P.-Y. Integration of online and offline health services: The role of doctor-patient online interaction. Pati Educ. Counsel. 2019, 102, 1905–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, W.; Wang, Y.; Luan, J.; Tang, P. The influence of physician information on patients’ choice of physician in mHealth services using China’s chunyu doctor app: Eye-tracking and questionnaire study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2019, 7, e15544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.A.; Garcıa-Magariño, I.; Nasralla, M.M.; Nazir, S. Agent-based simulators for empowering patients in self-care programs using mobile agents with machine learning. Mob. Inform. Syst. 2021, 2021, 5909281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamufleh, D.; Alshamari, A.S.; Alsobhi, A.S.; Ezzi, H.H.; Alruhaili, W.S. Exploring public attitudes toward e-government health applications used during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Comput. Inform. Sci. 2021, 14, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, M.H.; You, S.C.; Park, R.W.; Lee, S. Using an extended technology acceptance model to understand the factors influencing telehealth utilization after flattening the COVID-19 curve in South Korea: Cross-sectional survey study. JMIR Med. Inform. 2021, 9, e25435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouimet, A.G.; Wagner, G.; Raymond, L.; Pare, G. Investigating patients’ intention to continue using teleconsultation to anticipate post crisis momentum: Survey study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e22081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Wang, G.; Li, Y.; Ye, Q. Examining protection motivation and network externality perspective regarding the continued intention to use m-health apps. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 5684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, K.M.; Mendes, G.H.S.; Lizarelli, F.L.; Ganga, G.M.D. Assessing the telemedicine acceptance for adults in Brazil. Int. J. Health Care Q. Assu. 2021, 34, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molfenter, T.; Roget, N.; Chaple, M.; Behlman, S.; Cody, O.; Hartzler, B.; Johnson, E.; Nichols, M.; Stilen, P.; Becker, S. Use of telehealth in substance use disorder services during and after COVID-19: Online survey study. JMIR Ment. Health 2021, 8, e25835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Quart. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yan, M.; Filieri, R.; Raguseo, E.; Gorton, M. Mobile apps for healthy living: Factors influencing continuance intention for health apps. Tech. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 166, 120644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfi, W.B.; Nasr, I.B.; Kondrateva, G.; Hikkerova, L. The role of trust in intention to use the IoT in eHealth: Application of the modified UTAUT in a consumer context. Tech. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 167, 120688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.Z.; Hu, W.; Kaium, M.A.; Hoque, M.R.; Alam, M.M.D. Understanding the determinants of mHealth apps adoption in Bangladesh: A SEM-Neural network approach. Tech. Soc. 2020, 61, 101255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Octavius, G.S.; Antonio, F. Antecedents of intention to adopt mobile health (mHealth) application and its impact on intention to recommend: An evidence from Indonesian customers. Int. J. Telemed. App. 2021, 6698627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minghao, P.; Wei, G. Determinants of the behavioral intention to use a mobile nursing application by nurses in China. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 228. [Google Scholar]

- Rahi, S.; Ghani, M.A.; Ngah, A.H. Factors propelling the adoption of internet banking: The role of e-customer service, website design, brand image and customer satisfaction. Int. J. Busi. Inform. Syst. 2020, 33, 549–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamin, M.A.Y.; Alyoubi, B.A. Adoption of telemedicine applications among Saudi citizens during COVID-19 pandemic: An alternative health delivery system. J. Infect. Pub. Health 2020, 13, 1845–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, S.; Basak, R.; Carpenter, D.; Carpenter, B.J. Patient use of online medical records: An application of technology acceptance framework. Inform. Comput. Sec. 2020, 28, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liang, L.; Du, C.; Wu, Y. Implementation of online hospitals and factors influencing the adoption of mobile medical services in China: Cross-sectional survey study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2021, 9, e25960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamal, S.A.; Shafiq, M.; Kakria, P. Investigating acceptance of telemedicine services through an extended technology acceptance model (TAM). Techol. Soc. 2020, 60, 101212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, J.C.; Soutar, G.N. Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple-item scale. J. Retail. 2001, 77, 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theuri, M.M. The Factors Affecting Adoption of Online Doctor Services in Kenya: A Case Study of the Nairobi Hospital. Master’s Thesis, School of Computing and Informatics, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Shareef, M.A.; Simintiras, A.C.; Lal, B.; Weerakkody, V. A generalized adoption model for services: A cross-country comparison of mobile health (m-health). Govt. Inform. Quart. 2016, 33, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DeLone, W.H.; McLean, E.R. The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: A ten-year update. J. Manag. Inform. Syst. 2003, 19, 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kaium, M.A.; Bao, Y.; Alam, M.Z.; Hoque, M.R. Understanding continuance usage intention of mHealth in a developing country: An empirical investigation. Int. J. Pharm. Healthc. Mark. 2020, 14, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijay Anand, R.; Prabhu, J.; Kumar, P.J.; Manivannan, S.S.; Rajendran, S.; Kumar, K.R.; Susi, S.; Jothikumar, R. IoT role in prevention of COVID-19 and health care workforces behavioral intention in India: An empirical examination. Int. J. Pervasive Comput. Commun. 2020, 16, 331–340. [Google Scholar]

- Coulter, A. Engaging Patients in Healthcare; Open University Press: Maidenhead, UK, 2011; pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Asagbra, O.E.; Burke, D.; Liang, H. Why hospitals adopt patient engagement functionalities at different speeds? A moderated trend analysis. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2018, 111, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibbard, J.H.; Greene, J.; Overton, V. Patients with lower activation associated with higher costs: Delivery systems should know their patients’ Scores. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Hsu, P.Y.; Chang, Y.-W.; Shiau, W.-L. How does online doctor–patient interaction affect online consultation and offline medical treatment? Indust. Manag. Data Syst. 2020, 120, 196–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zaman, B.U. Adoption mechanism of telemedicine in underdeveloped country. Health Inform. J. 2020, 26, 1088–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhasan, A.; Audah, L.; Ibrahim, I.; Al-Sharaa, A.; Al-Ogaili, A.S.; Mohammed, J.M. A case study to examine doctors’intentions to use IoT healthcare devices in Iraq during COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Perva. Comput. Commu. 2020, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Jacques, R. Engagement as a design concept for multimedia. Can. J. Learn. Tech. 1995, 24, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guesalaga, R. The use of social media in sales: Individual and organizational antecedents, and the role of customer engagement in social media. Indust. Mark. Manag. 2016, 54, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.H.; Ward, T. The effect of automated service quality on Australian banks’ financial performance and the mediating role of customer satisfaction. Mark. Intelli Plan. 2006, 24, 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, M.S.; Ul Hassan, M.; Habibah, U. Impact of self-service technology (SST) service quality on customer loyalty and behavioral intention: The mediating role of customer satisfaction. Cog. Busi. Manag. 2018, 5, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bullet. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Education Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 1–816. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016; pp. 1–384. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, D.; Lin, Z.; Filieri, R.; Liu, R.; Zheng, M. Managing the product-harm crisis in the digital era: The role of consumer online brand community engagement. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 115, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doll, W.J.; Xia, W.; Torkzadeh, G. A confirmatory factor analysis of the end-user computing satisfaction instrument. MIS Quart. 1994, 18, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.H.; Zinkhan, G. Determinants of perceived website interactivity. J. Mark. 2008, 72, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Main Objective | Significant Findings/Hypotheses | Limitations | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bamufleh et al. [41] | To examine Saudi Arabians’ adoption intentions of e-government health applications during COVID-19. | ease of use→usefulness usefulness→ behavioral intention attitude→behavioral intention information quality→usefulness trust→attitude social influence→behavioral intention facilitating condition→behavioral intention | These authors did not perform any mediation test of organismic variables like attitude. | Our study explores if cognitive and affective variables like engagement and satisfaction mediate the paths between external stimuli and usage intention of telemedicine. |

| An et al. [42] | To explore the factors motivating the South Korean citizens to accept telemedicine services during the pandemic. | increased accessibility→usefulness enhanced care→usefulness ease of use→usefulness usefulness→attitude ease of use→attitude privacy and discomfort→attitude (negative relation) attitude→intention to use | ||

| Alam et al. [28] | To examine the factors of behavioral intention and actual usage behavior of Bangladeshi mobile health users and explore the impact of actual usage behavior on their mental well-being. | performance expectancy→behavioral intention effort expectancy→behavioral intention social influence→behavioral intention facilitating condition→behavioral intention habit→behavioral intention health consciousness→behavioral intention facilitating condition→actual usage behavior health consciousness→actual usage behavior behavioral intention→actual usage behavior self-quarantine→actual usage behavior actual usage behavior→mental well-being | ||

| Baudier et al. [11] | To investigate the usage intention of telemedicine services among end-users in Italy, France, the UK, and China. | habit→intention to use performance expectancy→intention to use risk→intention to use (negatively related) self-efficacy→effort expectancy personal innovativeness→effort expectancy availability→performance expectancy contamination avoidance→performance expectancy | ||

| Ouimet et al. [43] | To investigate Canadian patients’ continuous usage intention of telemedicine services. | usefulness→continuance usage intention quality→continuance usage intention quality→usefulness quality→trust expectation confirmation→quality expectation confirmation→usefulness | These authors did not use any theoretical framework to develop their research model. They also examined the consumers’ usage intention with the inclusion of a handful of variables, which might narrow the perspective of the study. | Our research is based on the S-O-R framework. It examines the context of telemedicine by adding seven stimuli, two organismic factors, and one response variable, which might broaden our study’s perspective. |

| Luo et al. [44] | To investigate the drivers of continuous usage intentions of telemedicine apps among Chinese residents. | vulnerability→self-efficacy vulnerability→response efficacy self-efficacy→attitude response efficacy→attitude self-efficacy→continued intention response efficacy→continued intention direct network externalities→attitude indirect network externalities→attitude indirect network externalities→continued intention attitude→continued intention self-efficacy→attitude→continued intention response efficacy→attitude→continued intention direct network externalities→attitude→continued intention indirect network externalities→attitude→continued intention | This study mainly emphasized the psychological factors of using telehealth apps. | The present model offers a possible solution to this limitation by adding telemedicine interface, attributes, and performance-related variables, such as performance and effort expectancies, functionality, information quality, etc. |

| Serrano et al. [45] | To examine the factors that influence telemedicine acceptance among adults in Brazil and test the moderation effects of disease complexity and the digital age on these relationships. | performance expectancy→intention to use security and reliability→intention to use security and reliability→performance expectancy | These studies did not use any psychological variables to examine the context of telemedicine. | We incorporate one cognitive variable (i.e., engagement) and one affective variable (i.e., satisfaction) into our model. |

| Molfenter et al. [46] | To investigate healthcare providers’ usage intentions of synchronous and asynchronous telemedicine services in the USA. | ease of use→future intention to use ease of use→usefulness usefulness→future intention to use ease of use→usefulness→future intention to use |

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 80 | 25.64 |

| Male | 232 | 74.35 |

| Age group (mean = 26.28, std. deviation = 5.53) | ||

| Below 20 | 15 | 4.80 |

| 21–25 | 138 | 44.23 |

| 26–30 | 105 | 33.65 |

| 31–35 | 26 | 8.33 |

| 36–40 | 18 | 5.76 |

| Above 40 | 10 | 3.20 |

| Occupation | ||

| Private employee | 19 | 6.1 |

| Government employee | 19 | 6.1 |

| Student | 173 | 55.4 |

| Business | 2 | 0.6 |

| Teacher | 58 | 18.6 |

| Unemployed | 17 | 5.4 |

| Other | 24 | 7.7 |

| Place of residence | ||

| Urban | 156 | 50.0 |

| Suburban | 64 | 20.5 |

| Rural | 92 | 29.48 |

| How often did you use telemedicine services over the last six months? (mean = 2.39, std. deviation = 1.31) | ||

| Once | 111 | 35.6 |

| Twice | 78 | 25.0 |

| Three times | 16 | 5.1 |

| Many times | 107 | 34.3 |

| Constructs | Estimate | CR | AVE | MSV | MaxR(H) | Alpha Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | PE5 | 0.788 | 0.841 | 0.572 | 0.424 | 0.852 | 0.840 |

| PE4 | 0.829 | ||||||

| PE3 | 0.725 | ||||||

| PE2 | 0.673 | ||||||

| EE | EE4 | 0.756 | 0.855 | 0.596 | 0.396 | 0.861 | 0.851 |

| EE3 | 0.837 | ||||||

| EE2 | 0.749 | ||||||

| EE1 | 0.742 | ||||||

| FC | FC3 | 0.801 | 0.831 | 0.622 | 0.340 | 0.841 | 0.824 |

| FC2 | 0.720 | ||||||

| FC1 | 0.841 | ||||||

| PV | PV3 | 0.686 | 0.829 | 0.622 | 0.324 | 0.896 | 0.780 |

| PV2 | 0.932 | ||||||

| PV1 | 0.725 | ||||||

| CA | CA4 | 0.663 | 0.833 | 0.556 | 0.203 | 0.840 | 0.828 |

| CA3 | 0.732 | ||||||

| CA2 | 0.782 | ||||||

| CA1 | 0.798 | ||||||

| ENG | ENG4 | 0.570 | 0.808 | 0.591 | 0.421 | 0.852 | 0.782 |

| ENG2 | 0.841 | ||||||

| ENG1 | 0.860 | ||||||

| FUNC | FUNC2 | 0.744 | 0.846 | 0.580 | 0.436 | 0.852 | 0.842 |

| FUNC3 | 0.697 | ||||||

| FUNC4 | 0.806 | ||||||

| FUNC5 | 0.794 | ||||||

| IQ | IQ1 | 0.726 | 0.862 | 0.611 | 0.449 | 0.867 | 0.848 |

| IQ3 | 0.802 | ||||||

| IQ4 | 0.829 | ||||||

| IQ5 | 0.765 | ||||||

| SAT | SAT2 | 0.765 | 0.884 | 0.657 | 0.420 | 0.887 | 0.884 |

| SAT3 | 0.845 | ||||||

| SAT4 | 0.821 | ||||||

| SAT5 | 0.809 | ||||||

| CUI | CUI1 | 0.848 | 0.879 | 0.708 | 0.449 | 0.880 | 0.877 |

| CUI4 | 0.855 | ||||||

| CUI5 | 0.821 |

| SAT | PE | EE | FC | PV | CA | ENG | FUNC | IQ | CUI | VIF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAT | 0.811 | 1.67 | |||||||||

| PE | 0.515 | 0.756 | 1.74 | ||||||||

| EE | 0.412 | 0.629 | 0.772 | 1.93 | |||||||

| FC | 0.255 | 0.470 | 0.583 | 0.789 | 1.48 | ||||||

| PV | 0.363 | 0.408 | 0.509 | 0.324 | 0.788 | 1.49 | |||||

| CA | 0.370 | 0.403 | 0.399 | 0.451 | 0.292 | 0.746 | 1.32 | ||||

| ENG | 0.547 | 0.482 | 0.526 | 0.306 | 0.421 | 0.398 | 0.769 | 1.87 | |||

| FUNC | 0.550 | 0.499 | 0.462 | 0.305 | 0.456 | 0.367 | 0.649 | 0.761 | 1.80 | ||

| IQ | 0.648 | 0.620 | 0.582 | 0.428 | 0.569 | 0.408 | 0.618 | 0.660 | 0.781 | 2.34 | |

| CUI | 0.636 | 0.651 | 0.466 | 0.324 | 0.357 | 0.446 | 0.553 | 0.514 | 0.670 | 0.841 |

| Indices | Recommended Value | The Obtained Value Measurement Model | The Obtained Value Structural Model |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMIN/df | <3 | 1.854 | 2.861 |

| CFI | ≥0.90 | 0.925 | 0.830 |

| GFI | ≥0.80 | 0.853 | 0.756 |

| AGFI | ≥0.80 | 0.822 | 0.717 |

| NFI | ≥0.90 | 0.853 | 0.762 |

| TLI | ≥0.90 | 0.914 | 0.813 |

| IFI | ≥0.90 | 0.926 | 0.831 |

| RMSEA | ≤0.08 | 0.052 | 0.077 |

| Hypothesized Paths | Estimate | SE. | CR. | P | Decision | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a: PE | ---> | ENG | 0.271 | 0.063 | 3.325 | *** | Accept |

| H1b: PE | ---> | SAT | 0.227 | 0.073 | 2.855 | *** | Accept |

| H1c: PE | ---> | CUI | 0.366 | 0.079 | 4.479 | *** | Accept |

| H2a: EE | ---> | PE | 0.572 | 0.060 | 8.322 | *** | Accept |

| H2b: EE | ---> | ENG | 0.345 | 0.057 | 4.096 | *** | Accept |

| H2c: EE | ---> | SAT | −0.052 | 0.063 | −0.664 | n.s. | Reject |

| H2d: EE | ---> | CUI | −0.052 | 0.063 | −0.692 | n.s. | Reject |

| H3a: FC | ---> | SAT | −0.056 | 0.055 | −0.979 | n.s. | Reject |

| H3b: FC | ---> | CUI | −0.035 | 0.053 | −0.659 | n.s. | Reject |

| H4: PV | ---> | CUI | −0.066 | 0.057 | −1.306 | n.s. | Reject |

| H5a: CA | ---> | PE | 0.237 | 0.076 | 3.924 | *** | Accept |

| H5b: CA | ---> | CUI | 0.138 | 0.070 | 2.389 | ** | Accept |

| H6a: FUNC | ---> | SAT | 0.187 | 0.050 | 3.169 | *** | Accept |

| H6b: FUNC | ---> | CUI | 0.037 | 0.049 | 0.675 | n.s. | Reject |

| H7a: IQ | ---> | SAT | 0.422 | 0.069 | 6.348 | *** | Accept |

| H7b: IQ | ---> | CUI | 0.293 | 0.071 | 4.543 | *** | Accept |

| H8a: ENG | ---> | SAT | 0.217 | 0.089 | 2.877 | *** | Accept |

| H8b: ENG | ---> | CUI | 0.129 | 0.086 | 1.857 | ** | Accept |

| H9: SAT | ---> | CUI | 0.234 | 0.075 | 3.307 | *** | Accept |

| Variance explained | R squared | ||||||

| PE | 0.383 | ||||||

| ENG | 0.300 | ||||||

| SAT | 0.339 | ||||||

| CUI | 0.493 | ||||||

| Path | Indirect Effect | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | p-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H10a: PE-ENG-CUI | 0.080 | 0.011 | 0.208 | *** | Mediated |

| H10b: EE-ENG-CUI | 0.489 | 0.337 | 0.701 | *** | Mediated |

| H11a: PE-SAT-CUI | 0.175 | 0.082 | 0.335 | *** | Mediated |

| H11b: EE-SAT-CUI | 0.433 | 0.286 | 0.604 | *** | Mediated |

| H11c: FC-SAT-CUI | −0.001 | −0.084 | 0.077 | n.s. | Not mediated |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amin, R.; Hossain, M.A.; Uddin, M.M.; Jony, M.T.I.; Kim, M. Stimuli Influencing Engagement, Satisfaction, and Intention to Use Telemedicine Services: An Integrative Model. Healthcare 2022, 10, 1327. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071327

Amin R, Hossain MA, Uddin MM, Jony MTI, Kim M. Stimuli Influencing Engagement, Satisfaction, and Intention to Use Telemedicine Services: An Integrative Model. Healthcare. 2022; 10(7):1327. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071327

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmin, Ruhul, Md. Alamgir Hossain, Md. Minhaj Uddin, Mohammad Toriqul Islam Jony, and Minho Kim. 2022. "Stimuli Influencing Engagement, Satisfaction, and Intention to Use Telemedicine Services: An Integrative Model" Healthcare 10, no. 7: 1327. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071327

APA StyleAmin, R., Hossain, M. A., Uddin, M. M., Jony, M. T. I., & Kim, M. (2022). Stimuli Influencing Engagement, Satisfaction, and Intention to Use Telemedicine Services: An Integrative Model. Healthcare, 10(7), 1327. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071327