A GDPR-Compliant Dynamic Consent Mobile Application for the Australasian Type-1 Diabetes Data Network

Abstract

:1. Introduction

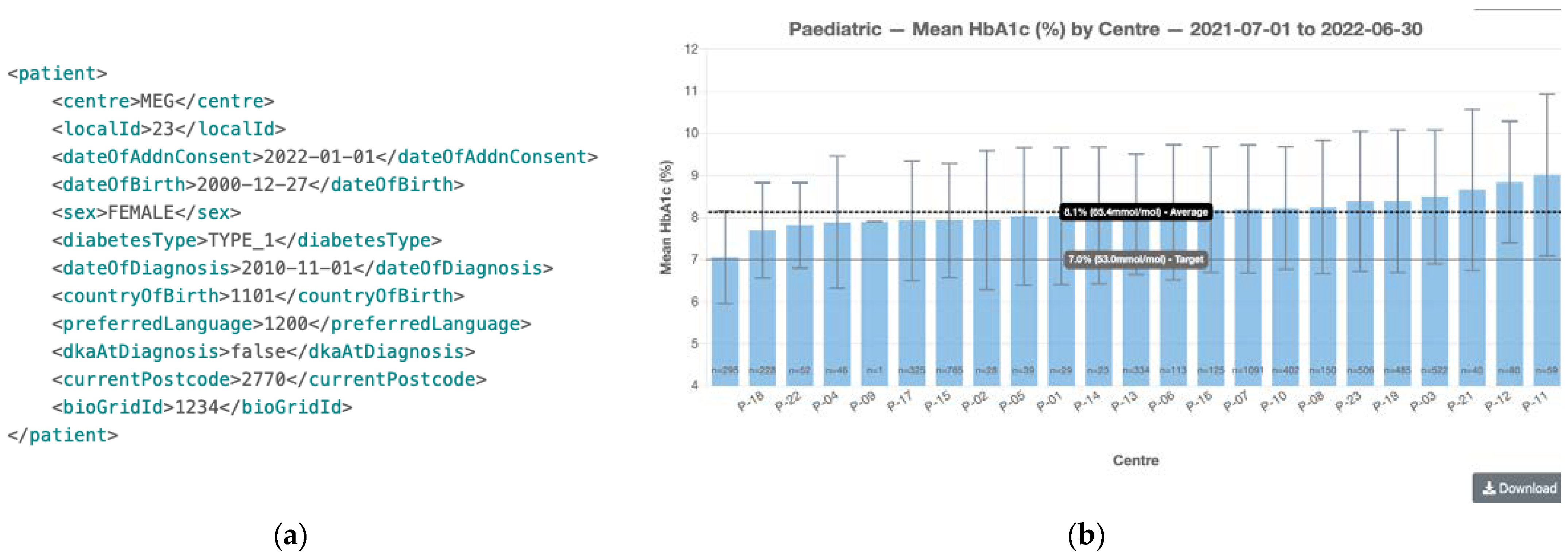

2. Background

2.1. The ADDN Project

2.2. GDPR Concepts

2.2.1. Controller, Processor and Data Subjects

2.2.2. Personal Data, Pseudonymisation and Safeguards

- (1)

- Name.

- (2)

- Address (all geographic subdivisions smaller than state, including street address, city county, and zip code).

- (3)

- All elements (except years) of dates related to an individual (including birthdate, admission date, discharge date, date of death, and exact age if over 89).

- (4)

- Telephone numbers.

- (5)

- Fax number.

- (6)

- Email address.

- (7)

- Social Security Number.

- (8)

- Medical record number.

- (9)

- Health plan beneficiary number.

- (10)

- Account number.

- (11)

- Certificate or license number.

- (12)

- Vehicle identifiers and serial numbers, including license plate numbers.

- (13)

- Device identifiers and serial numbers.

- (14)

- Web URL.

- (15)

- Internet Protocol (IP) address.

- (16)

- Finger or voice print.

- (17)

- Photographic image—photographic images are not limited to images of the face.

- (18)

- Any other characteristic that could uniquely identify the individual.

2.2.3. Legal Bases

- (1)

- Freely given—the data subjects must not be cornered into agreeing, noting that the imbalance between the data subject and controller can often make unencumbered consent difficult, e.g., patients may feel obliged or have concerns that the treatments they receive may be inferior if they do not agree. Furthermore, each usage of personal data should be given separate consent.

- (2)

- Specific—the consent must be collected for certain agreed activities or purposes unless explicitly identified as “general” research.

- (3)

- Informed—the data subject must fully understand the consent before making the decision, including an understanding of data processing activities and their purpose and any associated risks or consequences.

- (4)

- Unambiguous—it should be immediately clear whether the data subject has consented. Consent under GDPR cannot be implied, and explicit opt-in consent is required.

- (5)

- Withdrawal—individuals can withdraw their consent at any time, and this withdrawal should be made as easy as obtaining the original consent.

2.2.4. GDPR Consent Conditions

2.3. Dynamic Consent

2.3.1. mHealth

2.3.2. eConsent and Dynamic Consent

2.3.3. Implementation of Dynamic Consent

2.3.4. Challenges of Dynamic Consent

3. Dynamic Consent Implementation in ADDN

3.1. Recruitment and Onboarding

3.2. Sub-Project Consent Process

- Consent: shows when the current status of the patient consent is not “Consented”. By clicking this button, patients are requested to agree to the terms and conditions of the study, and hence they agree to opt-in to the research project. It is noted that at present, the ADDN Consent app is purely focused on obtaining patient consent for studies using the ADDN registry data and not for the collection of additional data from patients.

- Decline: this button shows when the status of the consent is not yet set (“Null”). By clicking this button, patients are able to freely decide to reject the consent task and thereby indicate that they do not wish their data to be used in the research.

- Withdraw: this button shows when the consent status is “Consented”. By clicking this button, patients can withdraw their consent and, thereafter, their data will be removed and no longer used in the given research project.

3.3. Patient View of Their Data

3.4. Incorporating Dynamic Consent Data into the ADDN Data Load

- <addnConsentContinue>: This indicates the patient has activated the app and made an opt-in decision of whether they still want to be in the registry or not, by clicking buttons on the “Onboarding” page (Figure 2b);

- <addnConsentTaskX>: This indicates the patient has made a decision regarding whether they wish to be involved in Research task X (e.g., <addnConsentTask3> for research task #3) by clicking buttons on the “Consent” page (Figure 4a);

- <dateOfAddnConsent>: This is the historical opt-out data collected by ADDN. It is noted that eventually it is expected that this field will be replaced by the above opt-in consent for all patients to comply with GDPR.

3.5. ADDN Consent Workflow

- A.

- General consent process: as described in Section 3.1, patients who did not opt-out will be instructed by clinicians when visiting the clinic to activate the mobile consent app and finish the onboarding process. In this stage, patients make their general consent decisions where they can choose to opt-out/decline/withdraw and be removed from the ADDN registry, whereupon they will not receive any further notifications.

- B.

- Sub-project consent process: as described in Section 3.2, in this example, two research requests are approved by the ADDN Study Group on 09/10/2023 and 20/10/2023. The ADDN registry administrator creates a view of the data for the patients that match the study criteria, e.g., 0–12 year-old boys, and subsequently creates a dynamic consent task #3 and #4 for these research projects. A notification is then sent to the target patient group’s mobile app. From this point, notifications are pushed to patients’ phones periodically until they make a decision (consent, decline, withdraw). Patients are allowed to modify their decision any time before the cut-off date—given here as 15/01/2024, when the next data load begins, and the centres start to send the updated data to ADDN.

- C

- Data load validation and merge: Patients’ decisions will be incorporated into the data load as inclusion criteria as described in Section 3.4.

- D.

- Research data created: for patients who have not opted-in, their data will be excluded from given research requests, and hence it will not be sent to researchers. In this example, the patients can choose to be involved in #3, but not for #4, i.e., the related data will be excluded when creating a dataset for research task #4.

3.6. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Optus Notifies Customers of Cyberattack Compromising Customer Information. 2022. Available online: https://www.optus.com.au/about/media-centre/media-releases/2022/09/optus-notifies-customers-of-cyberattack (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Arnold, B.B. Into the Breach—The Optus Data Hack. 2022. Available online: https://lsj.com.au/articles/into-the-breach/ (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Medibank Private Cyber Security Incident-Australian Cyber Security Centre. 2022. Available online: https://www.cyber.gov.au/acsc/view-all-content/alerts/medibank-private-cyber-security-incident (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Privacy Act Review—Discussion Paper. 2021. Available online: https://consultations.ag.gov.au/rights-and-protections/privacy-act-review-discussion-paper/ (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Attorney-General’s Department. Review of the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth)—Issues Paper; Attorney-General’s Department’s: Barton, ACT, Australia, 2020.

- OAIC. Privacy Legislation Amendment (Enforcement and Other Measures) Bill 2022; OAIC: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2022.

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data and on the Free Movement of such Data, and Repealing Directive 95/46/EC (General Data Protection Regulation) (Text with EEA Relevance); European Union: Strasbourg, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfus, M. Tougher Penalties for Serious Data Breaches. 2022. Available online: https://ministers.ag.gov.au/media-centre/tougher-penalties-serious-data-breaches-22-10-2022 (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Bietz, M.J.; Bloss, C.S.; Calvert, S.; Godino, J.G.; Gregory, J.; Claffey, M.P.; Sheehan, J.; Patrick, K. Opportunities and challenges in the use of personal health data for health research. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2016, 23, e42–e48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Couper, J.J.; Jones, T.W.; Chee, M.; Barrett, H.L.; Bergman, P.; Cameron, F.; Craig, M.E.; Colman, P.; Davis, E.E.; Donaghue, K.C.; et al. Determinants of Cardiovascular Risk in 7000 Youth with Type 1 Diabetes in the Australasian Diabetes Data Network. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bratina, N.; Auzanneau, M.; Birkebæk, N.; de Beaufort, C.; Cherubini, V.; Craig, M.E.; Dabelea, D.; Dovc, K.; Hofer, S.E.; Holl, R.W.; et al. Differences in retinopathy prevalence and associated risk factors across 11 countries in three continents: A cross-sectional study of 156,090 children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Pediatr. Diabetes 2022, 23, 1656–1664. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- OAIC. Privacy Act 1988; OAIC: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 1988.

- Wang, Z.; Stell, A.; Sinnott, R.O.; ADDN Study Group. The Impact of General Data Protection Regulation on the Australasian Type-1 Diabetes Platform. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 35th International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS), Shanghai, China, 21–23 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- The National Diabetes Services Scheme (NDSS). Available online: https://www.ndss.com.au/about-the-ndss/diabetes-facts-and-figures/ (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation. Available online: https://jdrf.org.au/ (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Clapin, H.; Phelan, H.; Bruns, L., Jr.; Sinnott, R.; Colman, P.; Craig, M.; Jones, T.; Australasian Diabetes Data Network (ADDN) Study Group. Australasian diabetes data network: Building a collaborative resource. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2016, 10, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Australia and New Zealand Society for Paediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes. Available online: https://apeg.org.au/ (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Australian Diabetes Society. Available online: https://diabetessociety.com.au/ (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Available online: https://www.aihw.gov.au/ (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Australian Medical Benefits Scheme. Available online: www.mbsonline.gov.au (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Available online: www.pbs.gov.au (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- 18 HIPAA Identifiers. Available online: https://www.luc.edu/its/aboutits/itspoliciesguidelines/hipaainformation/18hipaaidentifiers/ (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Cybersecurity, E.U.A. Pseudonymisation Techniques and Best Practices—Recommendations on Shaping Technology According to Data Protection and Privacy Provisions; ENISA: Attiki, Greece, 2019.

- Data overprotection. Nature 2015, 522, 391–392. [CrossRef]

- Maloy, J.W.; Bass, P.F., 3rd. Understanding Broad Consent. Ochsner J. 2020, 20, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Whitley, E.A.; Kanellopoulou, N.; Kaye, J. Consent and research governance in biobanks: Evidence from focus groups with medical researchers. Public Health Genom. 2012, 15, 232–242. [Google Scholar]

- Wiertz, S.; Boldt, J. Evaluating models of consent in changing health research environments. Med. Health Care Philos. 2022, 25, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.; Landman, A.B. Mobile Health. In Key Advances in Clinical Informatics: Transforming Health Care through Health Information Technology; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 183–196. [Google Scholar]

- Australia: Smartphone Penetration Rate 2017–2025|Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/321477/smartphone-user-penetration-in-australia/ (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- iOS-Health-Apple (AU). Available online: https://www.apple.com/au/ios/health/ (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Healow–Apps on Google Play. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.ecw.healow&hl=en_AU&gl=US (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Glucose Buddy Diabetes Tracker on the App Store. Available online: https://apps.apple.com/us/app/glucose-buddy-diabetes-tracker/id294754639 (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Google Health Studies—Apps on Google Play. Available online: https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.google.android.apps.health.research.studies&hl=en_AU&gl=US (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Silva, B.M.C.; Rodrigues, J.J.; de la Torre Díez, I.; López-Coronado, M.; Saleem, K. Mobile-health: A review of current state in 2015. J. Biomed. Inform. 2015, 56, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qudah, B.; Luetsch, K. The influence of mobile health applications on patient-healthcare provider relationships: A systematic, narrative review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 1080–1089. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Baysari, M.T.; Westbrook, J.I. Mobile Applications for Patient-centered Care Coordination: A Review of Human Factors Methods Applied to their Design, Development, and Evaluation. Yearb. Med. Inform. 2015, 24, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Schairer, C.E.; Rubanovich, C.K.; Bloss, C.S. How Could Commercial Terms of Use and Privacy Policies Undermine Informed Consent in the Age of Mobile Health? AMA J. Ethics 2018, 20, 864–872. [Google Scholar]

- Mont, M.C.; Sharma, V.; Pearson, S. EnCoRe: Dynamic Consent, Policy Enforcement and Accountable Information Sharing within and Across Organisations; Technical Report HPL-2012-36; HP Laboratories: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Teare, H.J.A.; Prictor, M.; Kaye, J. Reflections on dynamic consent in biomedical research: The story so far. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2021, 29, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascalzoni, D.; Melotti, R.; Pattaro, C.; Pramstaller, P.P.; Gögele, M.; De Grandi, A.; Biasiotto, R. Ten years of dynamic consent in the CHRIS study: Informed consent as a dynamic process. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2022, 30, 1391–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattaro, C.; Gögele, M.; Mascalzoni, D.; Melotti, R.; Schwienbacher, C.; De Grandi, A.; Foco, L.; D’elia, Y.; Linder, B.; Fuchsberger, C.; et al. The Cooperative Health Research in South Tyrol (CHRIS) study: Rationale, objectives, and preliminary results. J. Transl. Med. 2015, 13, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiel, D.B.; Platt, J.; Platt, T.; King, S.B.; Fisher, N.; Shelton, R.; Kardia, S.L. Testing an online, dynamic consent portal for large population biobank research. Public Health Genom. 2015, 18, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teare, H.J.A.; Hogg, J.; Kaye, J.; Luqmani, R.; Rush, E.; Turner, A.; Watts, L.; Williams, M.; Javaid, M.K. The RUDY study: Using digital technologies to enable a research partnership. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2017, 25, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Javaid, M.K.; Forestier-Zhang, L.; Watts, L.; Turner, A.; Ponte, C.; Teare, H.; Gray, D.; Gray, N.; Popert, R.; Hogg, J.; et al. The RUDY study platform—A novel approach to patient driven research in rare musculoskeletal diseases. Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 2016, 11, 150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Steinsbekk, K.S.; Kåre Myskja, B.; Solberg, B. Broad consent versus dynamic consent in biobank research: Is passive participation an ethical problem? Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 21, 897–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, K.; Sanders, C.; Whitley, E.A.; Lund, D.; Kaye, J.; Dixon, W.G. Patient Perspectives on Sharing Anonymized Personal Health Data Using a Digital System for Dynamic Consent and Research Feedback: A Qualitative Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016, 18, e66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Status/Action | Consent | Withdraw | Decline |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consented: the patient has opted-in to the study and their data can be used in the study | N | Y | N |

| Withdrawn: the patient has withdrawn their consent from an ongoing study, they wish their data to be removed and they no longer wish to be notified about the study | Y | N | N |

| Declined: the patient does not wish to be involved in a given (proposed) study and no longer wishes to be notified | Y | N | N |

| Null: no action yet, notifications can still be received | Y | N | Y |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Stell, A.; Sinnott, R.O.; the ADDN Study Group. A GDPR-Compliant Dynamic Consent Mobile Application for the Australasian Type-1 Diabetes Data Network. Healthcare 2023, 11, 496. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11040496

Wang Z, Stell A, Sinnott RO, the ADDN Study Group. A GDPR-Compliant Dynamic Consent Mobile Application for the Australasian Type-1 Diabetes Data Network. Healthcare. 2023; 11(4):496. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11040496

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zhe, Anthony Stell, Richard O. Sinnott, and the ADDN Study Group. 2023. "A GDPR-Compliant Dynamic Consent Mobile Application for the Australasian Type-1 Diabetes Data Network" Healthcare 11, no. 4: 496. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11040496

APA StyleWang, Z., Stell, A., Sinnott, R. O., & the ADDN Study Group. (2023). A GDPR-Compliant Dynamic Consent Mobile Application for the Australasian Type-1 Diabetes Data Network. Healthcare, 11(4), 496. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11040496