Why Individuals Do (Not) Use Contact Tracing Apps: A Health Belief Model Perspective on the German Corona-Warn-App

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Health Belief Model

HBM in the Context of Contact Tracing Apps

3. Research Hypotheses

3.1. Perceived Susceptibility

3.2. Perceived Severity

3.3. Perceived Benefits

3.4. Perceived Barriers

3.5. Cues to Action

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Model

4.2. Data Collection

5. Results

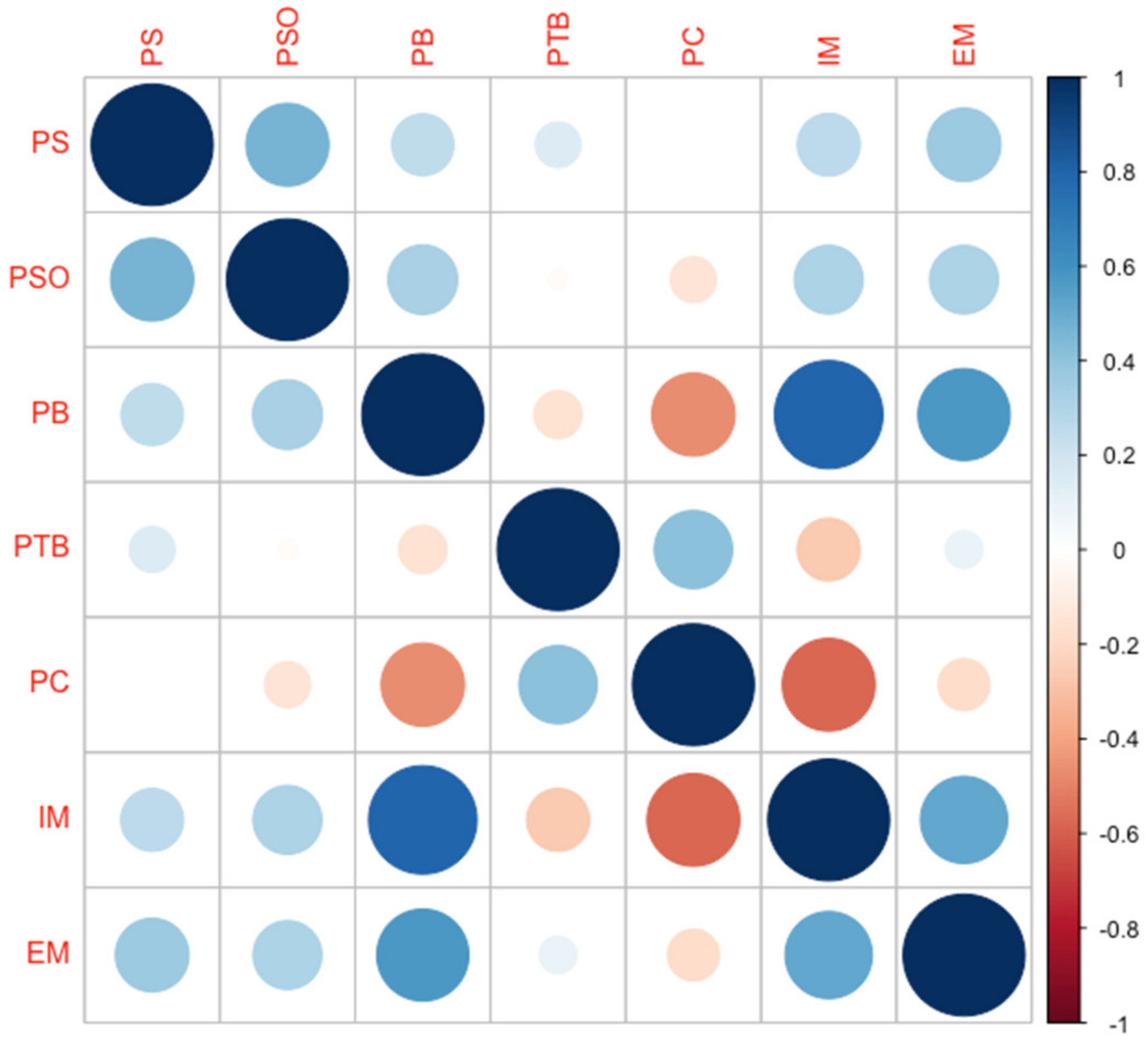

5.1. Descriptive Analysis

5.2. Regression Analysis

6. Discussion

Limitations and Future Work

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Perceived susceptibility (PS)

- PS1. My chances of being infected by COVID-19 are great.

- PS2. My physical health makes it more likely that an infection by COVID-19 will have serious consequences.

- PS3. I worry a lot about being infected by COVID-19.

- PS4. My job involves a high risk to be infected by COVID-19.

- PS5. My daily life involves a high risk to be infected by COVID-19.

- 2.

- Perceived severity related to medical consequences on oneself (PMC)

- PMC1. The thought of COVID-19 scares me.

- PMC2. COVID-19 is a hopeless illness.

- PMC3. Health issues I would experience from COVID-19 would last a long time.

- PMC4. If I got infected by COVID-19, it would be more serious than other diseases.

- PMC5. If I had COVID-19 my whole life would change.

- 3.

- Perceived severity on others (PSO) (self-made)

- PSO1. The health of my friends would be at risk if I became infected with COVID-19.

- PSO2. My family’s health would be at risk if I became infected with COVID-19.

- PSO3. The health of my work colleagues would be at risk if I became infected with COVID-19.

- PSO4. The health of other contacts would be at risk if I became infected with COVID-19.

- 4.

- Perceived severity related to social consequences (PSC)

- PSC1. My financial security would be at risk if I became infected with COVID-19.

- PSC2. If I became infected with COVID-19, my career would be at risk.

- PSC3. My social relationships (family, friends) would be at risk if I became infected with COVID-19.

- 5.

- Perceived benefits (PB)

- PB1. Using the Corona-Warn-App makes me feel safer.

- PB2. I have a lot to gain by using the Corona-Warn-App.

- PB3. The Corona-Warn-App can help me to identify contacts to infected individuals.

- PB4. If I use the Corona-Warn-App I am able to warn others in case I am infected with COVID-19.

- PB5. I feel that the usage of the Corona-Warn-App is beneficial to combat COVID-19.

- 6.

- Perceived technical barriers (PTB) (self-made)

- PTB1. I am afraid to use the Corona-Warn-App because I don’t understand how it works.

- PTB2. I don’t know how to go about using the Corona-Warn-App.

- PTB3. Installing the Corona-Warn-App takes too much time.

- PTB4. The installation of the Corona-Warn-App is associated with technical problems.

- 7.

- Perceived barriers related to privacy concerns (PC) [33]

- PC1. I think the Corona-Warn-App gathers far too much of my personal information.

- PC2. I worry that the Corona-Warn-App leaks my personal information to third-parties.

- PC3. I am concerned that the Corona-Warn-App violates my privacy.

- PC4. I am concerned that the Corona-Warn-App misuses my personal information.

- PC5. I think that the Corona-Warn-App collects my location data.

- 8.

- Intrinsic motivation (IM) (self-made)

- IM1. I feel responsible to register a positive test result into the Corona-Warn-App.

- IM2. I feel responsible to use the Corona-Warn-App regularly to inform myself of potential risk encounters.

- 9.

- Extrinsic motivation (EM) (self-made)

- EM1. Potential infections of family members or friends with COVID−19 affect my decision to use the Corona-Warn-App.

- EM2. The number of COVID-19 infections in Germany affects my decision to use the Corona-Warn-App.

- EM3. The number of COVID-19 infections in the world affects my decision to use the Corona-Warn-App.

- EM4. Using the Corona-Warn-App has advantages for my social life.

- EM5. The use of the Corona-Warn-App is requested for my work.

Appendix B

References

- Eurosurveillance Editorial Team Note from the Editors: World Health Organization Declares Novel Coronavirus (2019-NCoV) Sixth Public Health Emergency of International Concern. Euro Surveill. 2020, 25, 2019–2020. [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reelfs, J.H.; Poese, I.; Hohlfeld, O. Corona-Warn-App: Tracing the Start of the Official COVID-19 Exposure Notification App for Germany. arXiv 2020, 19–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinch, R.; Probert, W.; Nurtay, A.; Kendall, M.; Wymant, C.; Hall, M.; Lythgoe, K.; Bulas, C.; Zhao, L.; Stewart, A.; et al. Effective Configurations of a Digital Contact Tracing App: A Report to NHSX. Available online: https://cdn.theconversation.com/static_files/files/1009/Report_-_Effective_App_Configurations.pdf?1587531217 (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Becker, K.; Feld, C. Was Heißt Zentralisiert Oder Dezentral? Available online: https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/coronavirus-app-101.html (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- Neuerer, D.; Olk, J.; Hoppe, T. Politiker Stellen Strengen Datenschutz Der Corona-Warn-App Infrage. Available online: https://www.handelsblatt.com/politik/deutschland/kampf-gegen-die-pandemie-politiker-stellen-strengen-datenschutz-der-corona-warn-app-infrage/26570478.html (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Schar, P. Corona: Datenschutz Vor Menschenleben? Available online: https://www.eaid-berlin.de/corona-datenschutz-vor-menschenleben/ (accessed on 11 March 2021).

- Harborth, D.; Pape, S. A Privacy Calculus Model for Contact Tracing Apps: Analyzing the German Corona-Warn-App. In ICT Systems Security and Privacy Protection. SEC 2022. IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology; Meng, W., Fischer-Hübner, S., Jensen, C.D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 648, pp. 3–19. ISBN 978-3-031-06975-8. [Google Scholar]

- Pape, S.; Harborth, D.; Kröger, J.L. Privacy Concerns Go Hand in Hand with Lack of Knowledge: The Case of the German Corona-Warn-App. In Proceedings of the ICT Systems Security and Privacy Protection. SEC 2021, Oslo, Norway, 22–24 June 2021; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstock, I.M. Historical Origins of the Health Belief Model. Health Educ. Behav. 1974, 2, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walrave, M.; Waeterloos, C.; Ponnet, K. Adoption of a Contact Tracing App for Containing COVID-19: A Health Belief Model Approach. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillon, M.; Kergall, P. Attitudes and Opinions on Quarantine and Support for a Contact-Tracing Application in France during the COVID-19 Outbreak. Public Health 2020, 188, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom, A.G.; Wenz, A.; Cornesse, C.; Rettig, T.; Fikel, M.; Friedel, S.; Möhring, K.; Naumann, E.; Reifenscheid, M.; Krieger, U. Barriers to the Large-Scale Adoption of the COVID-19 Contact-Tracing App in Germany: Survey Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e23362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, E.C.; Murpy, E.M.; Grybosky, K. The Health Belief Model. The Wiley Encyclopedia of Health Psychology. Cambridge Handb. Psychol. Health Med. Second Ed. 2020, 2, 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Glanz, K.; Rimer, B.K.; Viswanath, K. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice; APA: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; ISBN 9780787996147. [Google Scholar]

- Champion, V.L. Instrument Development for Health Belief Model Constructs. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 1984, 6, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, V.L. Instrument Refinement for Breast Cancer Screening Behaviors. Nurs. Res. 1993, 42, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, V.L. Revised Susceptibility, Benefits, and Barriers Scale for Mammography Screening. Res. Nurs. Health 1999, 22, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee Champion, V. Use of the Health Belief Model in Determining Frequency of Breast Self-examination. Res. Nurs. Health 1985, 8, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.J.; Humiston, S.G.; Marcuse, E.K.; Zhao, Z.; Dorell, C.G.; Howes, C.; Hibbs, B. Parental Delay or Refusal of Vaccine Doses, Childhood Vaccination Coverage at 24 Months of Age, and the Health Belief Model. Public Health Rep. 2011, 126, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gerend, M.A.; Shepherd, J.E. Predicting Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Uptake in Young Adult Women: Comparing the Health Belief Model and Theory of Planned Behavior. Ann. Behav. Med. 2012, 44, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Champion, V.L.; Skinner, C.S. The Health Belief Model. Health Behav. Health Educ. Theory Res. Pract. 2008, 4, 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Yehualashet, S.S.; Asefa, K.K.; Mekonnen, A.G.; Gemeda, B.N.; Shiferaw, W.S.; Aynalem, Y.A.; Bilchut, A.H.; Derseh, B.T.; Mekuria, A.D.; Mekonnen, W.N.; et al. Predictors of Adherence to COVID-19 Prevention Measure among Communities in North Shoa Zone, Ethiopia Based on Health Belief Model: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, K.K.; Chen, J.H.; Yu, E.W.Y.; Wu, A.M.S. Adherence to COVID-19 Precautionary Measures: Applying the Health Belief Model and Generalised Social Beliefs to a Probability Community Sample. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2020, 12, 1205–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.P.; Alias, H.; Wong, P.F.; Lee, H.Y.; AbuBakar, S. The Use of the Health Belief Model to Assess Predictors of Intent to Receive the COVID-19 Vaccine and Willingness to Pay. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 2204–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonker, M.; de Bekker-Grob, E.; Veldwijk, J.; Goossens, L.; Bour, S.; Mölken, M.R. Van COVID-19 Contact Tracing Apps: Predicted Uptake in the Netherlands Based on a Discrete Choice Experiment. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horstmann, K.T.; Buecker, S.; Krasko, J.; Kritzler, S.; Terwiel, S. Who Does or Does Not Use the “Corona-Warn-App” and Why? Eur. J. Public Health 2021, 31, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munzert, S.; Selb, P.; Gohdes, A.; Stoetzer, L.F.; Lowe, W. Tracking and Promoting the Usage of a COVID-19 Contact Tracing App. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossler, R.E.; Johnston, A.C.; Lowry, P.B.; Hu, Q.; Warkentin, M.; Baskerville, R. Future Directions for Behavioral Information Security Research. Comput. Secur. 2013, 32, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjerid, I.; Peer, E.; Acquisti, A. BEYOND THE PRIVACY PARADOX: OBJECTIVE VERSUS RELATIVE RISK IN PRIVACY DECISION MAKING. MIS Q. 2018, 42, 465–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clair, R.; Gordon, M.; Kroon, M.; Reilly, C. The Effects of Social Isolation on Well-Being and Life Satisfaction during Pandemic. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Wyl, V.; Hoeglinger, M.; Sieber, C.; Kaufmann, M.; Moser, A.; Serra-Burriel, M.; Ballouz, T.; Menges, D.; Frei, A.; Puhan, M. Are COVID-19 Proximity Tracing Apps Working under Real-World Conditions? Indicator Development and Assessment of Drivers for App (Non-) Use. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraunhofer AISEC Pandemic Contact Tracing Apps: DP-3T, PEPP-PT NTK, and ROBERT from a Privacy Perspective. Cryptol. ePrint Arch. Rep. 2020. Available online: https//eprint.iacr.org/2020/489 (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- Gu, J.; Xu, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhang, C.; Ling, H. Privacy Concerns for Mobile App Download: An Elaboration Likelihood Model Perspective. Decis. Support Syst. 2017, 94, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harborth, D.; Pape, S. Investigating Privacy Concerns Related to Mobile Augmented Reality Applications – A Vignette Based Online Experiment. Comput. Human Behav. 2021, 122, 106833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallerand, R.J. Toward A Hierarchical Model of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 29, 271–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, C. LimeSurvey Project Team. Available online: http://www.limesurvey.org (accessed on 10 July 2022).

- EUROSTAT. EUROSTAT. 2018. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/de/home (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- statista Marktanteile Der Führenden Mobilen Betriebssysteme an Der Internetnutzung Mit Mobiltelefonen in Deutschland von Januar 2009 Bis September 2020. Available online: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/184332/umfrage/marktanteil-der-mobilen-betriebssysteme-in-deutschland-seit-2009/ (accessed on 3 February 2021).

- Holgado–Tello, F.P.; Chacón–Moscoso, S.; Barbero–García, I.; Vila–Abad, E. Polychoric versus Pearson Correlations in Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Ordinal Variables. Qual. Quant. 2010, 44, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinde, J.; Demétrio, C.G.B. Overdispersion: Models and Estimation. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 1998, 27, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadden, D. Quantitative Methods for Analyzing Travel Behavior of Individuals: Some Recent Developments; EconPapers: Örebro, Sweden, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Storeng, K.T.; de Bengy Puyvallée, A. The Smartphone Pandemic: How Big Tech and Public Health Authorities Partner in the Digital Response to COVID-19. Glob. Public Health 2021, 16, 1482–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | N | % | Demographics | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Gender | ||||

| 18–29 years | 371 | 21.17% | Female | 894 | 51.03% |

| 30–39 years | 316 | 18.04% | Male | 853 | 48.69% |

| 40–49 years | 329 | 18.78% | Diverse | 4 | 0.23% |

| 50–59 years | 431 | 24.60% | Prefer not to say | 1 | 0.05% |

| 60 years and older | 305 | 17.41% | Education | ||

| Net income | No degree | 8 | 0.46% | ||

| 500€−1000€ | 160 | 9.13% | Secondary school | 187 | 10.67% |

| 1000€−2000€ | 402 | 22.95% | Secondary school † | 574 | 32.76% |

| 2000€−3000€ | 404 | 23.06% | A levels | 430 | 24.54% |

| 3000€−4000€ | 314 | 17.92% | Bachelor’s degree | 240 | 13.70% |

| More than 4000€ | 292 | 16.67% | Master’s degree | 285 | 16.27% |

| Prefer not to say | 180 | 10.27% | Doctorate | 28 | 1.60% |

| CWA | 0 | 1 | p-Value Significance of Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (Cronbach’s ) | N = 856 (Mean, sd) | N = 896 (Mean, sd) | ||

| Perceived Susceptibility () | 3.40 (1.35) | 3.81 (1.31) | <0.001 | |

| Perceived Medical Consequences () | 3.86 (1.49) | 4.49 (1.17) | <0.001 | |

| Perceived Severity on Others () | 4.32 (1.64) | 4.92 (1.42) | <0.001 | |

| Perceived Social Consequences () | 3.04 (1.53) | 3.12 (1.52) | 0.308 | |

| Perceived Benefits () | 3.05 (1.35) | 4.72 (1.22) | <0.001 | |

| Perceived Technical Barriers () | 2.74 (1.41) | 1.60 (1.07) | <0.001 | |

| Privacy Concerns () | 4.64 (1.70) | 2.57 (1.52) | <0.001 | |

| Intrinsic Motivation () | 3.25 (1.68) | 5.97 (1.18) | <0.001 | |

| Extrinsic Motivation () | 2.33 (1.27) | 3.41 (1.45) | <0.001 | |

| (1) Base Model (N = 1752) | (2) Full Model (N = 1571) | |

| DV: Are you using the Corona-Warn-App on your smartphone? (y/n) | ||

| Perceived Susceptibility | 0.177 * (2.261) | 0.176 * (2.012) |

| Perceived Medical Consequences | −0.080 (−1.023) | 0.011 (0.124) |

| Perceived Severity on Others | −0.163 ** (−2.636) | −0.227 *** (−3.301) |

| Perceived Social Consequences | 0.052 (0.859) | 0.058 (0.899) |

| Perceived Benefits | 0.210 ** (2.650) | 0.218 * (2.485) |

| Perceived Technical Barriers | −0.631 *** (−9.467) | −0.637 *** (−8.693) |

| Privacy Concerns | −0.329 *** (−6.497) | −0.358 *** (−6.457) |

| Intrinsic Motivation | 0.749 *** (11.029) | 0.775 *** (10.333) |

| Extrinsic Motivation | 0.416 *** (5.767) | 0.433 *** (5.409) |

| Income 5 (€500 to €1000) | −0.831 ** (−2.404) | |

| Age, gender, education, smartphone experience, SARS-CoV-2 risk group (participant herself or family/close relatives) | Not significant | |

| DV: CWA Use (y/n) | Marginal Effect |

|---|---|

| Perceived Susceptibility | 0.017 |

| Perceived Severity on Others | −0.020 |

| Perceived Benefits | 0.021 |

| Perceived Technical Barriers | −0.063 |

| Privacy Concerns | −0.035 |

| Intrinsic Motivation | 0.074 |

| Extrinsic Motivation | 0.047 |

| Income 5 (€500 to €1000) | −0.098 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Harborth, D.; Pape, S.; McKenzie, L.T. Why Individuals Do (Not) Use Contact Tracing Apps: A Health Belief Model Perspective on the German Corona-Warn-App. Healthcare 2023, 11, 583. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11040583

Harborth D, Pape S, McKenzie LT. Why Individuals Do (Not) Use Contact Tracing Apps: A Health Belief Model Perspective on the German Corona-Warn-App. Healthcare. 2023; 11(4):583. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11040583

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarborth, David, Sebastian Pape, and Lukas Tom McKenzie. 2023. "Why Individuals Do (Not) Use Contact Tracing Apps: A Health Belief Model Perspective on the German Corona-Warn-App" Healthcare 11, no. 4: 583. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11040583

APA StyleHarborth, D., Pape, S., & McKenzie, L. T. (2023). Why Individuals Do (Not) Use Contact Tracing Apps: A Health Belief Model Perspective on the German Corona-Warn-App. Healthcare, 11(4), 583. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11040583