Determinants of Healthcare Use Based on the Andersen Model: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

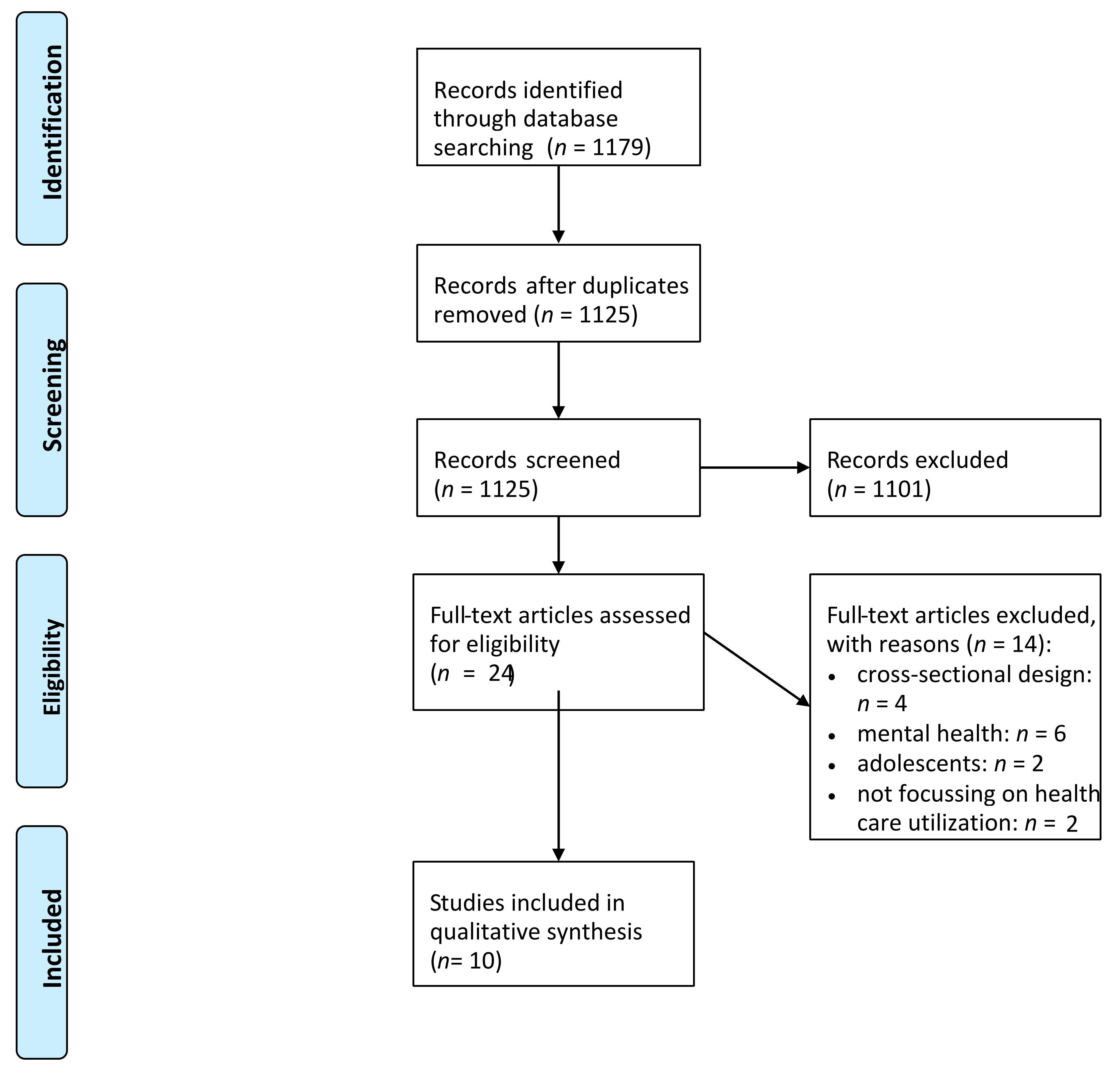

2.2. Study Selection

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

2.4. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Included Studies

3.2. Predisposing Characteristics

3.3. Enabling Resources

3.4. Need Factors

3.5. Psychosocial Factors

3.6. Quality Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andersen, R.M. Revisiting the Behavioral Model and Access to Medical Care: Does It Matter? J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.; König, H.-H. Beyond symptoms: Why do patients see the doctor? BJGP Open 2020, 4, bjgpopen20x101088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agyemang-Duah, W.; Peprah, C.; Arthur-Holmes, F. Predictors of healthcare utilisation among poor older people under the livelihood empowerment against poverty programme in the Atwima Nwabiagya District of Ghana. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madyaningrum, E.; Chuang, Y.-C.; Chuang, K.-Y. Factors associated with the use of outpatient services among the elderly in Indonesia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018, 18, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Babitsch, B.; Gohl, D.; Von Lengerke, T. Re-revisiting Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use: A systematic review of studies from 1998–2011. GMS Psycho-Soc.-Med. 2012, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newall, N.; McArthur, J.; Menec, V.H. A longitudinal examination of social participation, loneliness, and use of physician and hospital services. J. Aging Health 2015, 27, 500–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hajek, A.; Kretzler, B.; König, H.-H. Determinants of healthcare use based on the Andersen model: A study protocol for a systematic review of longitudinal studies. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e044435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuhldreher, N.; Konnopka, A.; Wild, B.; Herzog, W.; Zipfel, S.; Löwe, B.; König, H.H. Cost-of-illness studies and cost-effectiveness analyses in eating disorders: A systematic review. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2012, 45, 476–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohls, J.K.; Koenig, H.-H.; Raynik, Y.I.; Hajek, A. A systematic review of the association of anxiety with health care utilization and costs in people aged 65 years and older. J. Affect. Disord. 2018, 232, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.; Kretzler, B.; König, H.-H. Determinants of frequent attendance in primary care. A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 595674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Snih, S.; Markides, K.S.; Ray, L.A.; Freeman, J.L.; Ostir, G.V.; Goodwin, J.S. Predictors of healthcare utilization among older Mexican Americans. Ethn. Dis. 2006, 16, 640–646. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Clay, O.J.; Roth, D.L.; Safford, M.M.; Sawyer, P.L.; Allman, R.M. Predictors of overnight hospital admission in older African American and Caucasian Medicare beneficiaries. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biomed. Sci. Med Sci. 2011, 66, 910–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gabet, M.; Grenier, G.; Cao, Z.; Fleury, M.-J. Predictors of emergency department use among individuals with current or previous experience of homelessness. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public health 2019, 16, 4965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hadwiger, M.; König, H.-H.; Hajek, A. Determinants of frequent attendance of outpatient physicians: A longitudinal analysis using the German socio-economic panel (GSOEP). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hajek, A.; Bock, J.-O.; König, H.-H. Which factors affect health care use among older Germans? Results of the German ageing survey. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017, 17, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hajek, A.; Brettschneider, C.; Eisele, M.; Kaduszkiewicz, H.; Mamone, S.; Wiese, B.; Weyerer, S.; Werle, J.; Fuchs, A.; Pentzek, M.; et al. Correlates of hospitalization among the oldest old: Results of the AgeCoDe–AgeQualiDe prospective cohort study. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 32, 1295–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.; Brettschneider, C.; van den Bussche, H.; Kaduszkiewicz, H.; Oey, A.; Wiese, B.; Weyerer, S.; Werle, J.; Fuchs, A.; Pentzek, M.; et al. Longitudinal Analysis of Outpatient Physician Visits in the Oldest Old: Results of the AgeQualiDe Prospective Cohort Study. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2018, 22, 689–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajek, A.; König, H.H. Locus of control and frequency of physician visits: Results of a population-based longitudinal study in Germany. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 414–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-K.; Lee, M. Factors associated with health services utilization between the years 2010 and 2012 in Korea: Using Andersen’s behavioral model. Osong Public Health Res. Perspect. 2016, 7, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stein, J.A.; Andersen, R.M.; Koegel, P.; Gelberg, L. Predicting health services utilization among homeless adults: A prospective analysis. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2000, 11, 212–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, A.C.; Trivedi, P.K. Microeconometrics: Methods and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Initiative, S. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int. J. Surg. 2014, 12, 1495–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Von Hippel, P.T. New confidence intervals and bias comparisons show that maximum likelihood can beat multiple imputation in small samples. Struct. Equ. Modeling Multidiscip. J. 2016, 23, 422–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, P.D. Missing Data; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari, A.; Wagner, T. Self-reported utilization of health care services: Improving measurement and accuracy. Med Care Res. Rev. 2006, 63, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brüderl, J.; Ludwig, V. Fixed-effects panel regression. In The SAGE Handbook of Regression Analysis and Causal Inference; Wolf, C., Ed.; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 327–357. [Google Scholar]

- Gelberg, L.; Andersen, R.M.; Leake, B.D. The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations: Application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv. Res. 2000, 34, 1273. [Google Scholar]

| #1 | Health care |

| #2 | Health service * |

| #3 | #1 OR #2 |

| #4 | Use |

| #5 | Utili * |

| #6 | #4 OR #5 |

| #7 | #3 AND #6 |

| #8 | GP visits |

| #9 | Hospital admission |

| #10 | Hospitalization |

| #11 | Specialist visits |

| #12 | Doctor visits |

| #13 | Physician visits |

| #14 | General Practitioner visits |

| #15 | #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 |

| #16 | Andersen model |

| First Author | Country | Assessment of Health Care Utilization | Waves and Duration | Sample Description | Sample Size; Age; Females in Total Sample | Results: Predisposing Factors | Results: Enabling Factors | Results: Need Factors | Results: Psychosocial Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al Snih (2006) [12] | United States | Number of physician visits and hospitalizations during the last twelve months | Two waves from 1993 to 1996 | Hispanic Established Population from the Epidemiological Study of the Elderly | n = 1987 M: 72.6 SD: 6.1 ≥65 59.5% | According to multiple regression analysis, age (ß = 0.04, p < 0.05) and being female (ß = 0.97, p < 0.0001) were related to physician visits. Marital status, education and nativity remained insignificant. | Receiving Medicare only (ß = 0.89, p < 0.05) or Medicare and Medicaid (ß = 1.33, p < 0.001) was significantly associated with physician visits. Number of children, financial strain and having a usual source of care were not significant predictors. | Some medical conditions, such as diabetes, were significantly correlated with both physician visits (ß = 1.10, p < 0.0001) and number of hospitalizations (ß = 0.94, p < 0.001), as well as the number of medications (physician: ß = 0.65, p < 0.0001, hospital: ß = 0.33, p < 0.0001). Having a limitation in the activities of daily life was related to hospitalizations (ß = 2.74, p < 0.0001). Cognitive impairment and depressive symptoms remained insignificant. | Not applicable |

| Clay (2011) [13] | United States | Time since the last nonsurgical overnight hospital admission | Nine waves from 1999 to 2005 | Community-dwelling adults aged 65 years and older | n = 942 M: 75.3 SD: 6.7 65–106 50.7% | Univariate Cox proportional hazard ratios show that race (African American vs. Caucasian: OR: 0.74, 95% CI: 0.59–0.93) and age (OR: 1.03, 95% CI: 1.01–1.05) were significantly related to the outcome variable. Gender, marital status, education and residence were not. | Social support (OR: 1.04, 95% CI: 1.00–1.09) and perceived discrimination (OR: 0.88, 95% CI: 0.77–0.99) were significantly correlated with the time gap. Mental state and private insurance were not. | Physical health (OR: 0.97, 95% CI: 0.96–0.98), limitations among activities of daily life (OR: 1.19, 95% CI: 1.10–1.29) and physical performance (OR: 0.91, 95% CI: 0.89–0.95) were significantly associated with the time since the last nonsurgical overnight hospital admission.Depressive symptoms (OR: 1.09, 95% CI: 1.04–1.14), anxiety (OR: 0.96, 95% CI: 0.93–0.98) and mental health (OR: 0.98, 95% CI: 0.97–0.99) were significantly correlated with the time gap. | Not applicable |

| Gabet (2019) [14] | Canada | Having used an emergency department during the last twelve months | Two waves from 2017 to 2018 | Homeless people from Montreal | n = 270 18–39: 5.2% 40–49: 38.2% ≥50: 56.6% 42.2% | Not applicable | According to multiple logistic regression, specialized ambulatory service use (OR: 1.74, 95% CI: 1.00–3.01) and stigma (OR: 0.70, 95% CI: 0.56–0.89) were significantly associated with emergency department use. | Substance use disorders (OR: 1.70, 95% CI: 1.01–2.87) and perceived physical health (OR: 0.75, 95% CI: 0.58–0.98) were significantly correlated with emergency department utilization. | Not applicable |

| Hadwiger (2019) [15] | Germany | Six or more physician consultations during the last three months | Seven waves from 2002 to 2014 | German Socio-Economic-Panel | n = 28,574 M: 53.6 SD: 16.7 17–102 55.6% | The regression results show that being a frequent attender was significantly associated with lower age (OR: 0.95, 95% CI: 0.94–0.96), having a partner (OR: 1.22, 95% CI: 1.07–1.41) and non-working (OR: 1.35, 95% CI: 1.22–1.50). | Logarithmized equivalent income and having a private health insurance remained insignificant. | Frequent attenders were likely to have a lower physical health (reversed OR: 1.11, 95% CI: 1.11–1.12) and mental health composite score (reversed OR: 1.05, 95% CI: 1.05–1.05). | Not applicable |

| Hajek (2017a) [19] | Germany | Number of physician visits during the last three months | Two waves from 2005 to 2010 | German Socio-Economic-Panel | n = 11,310 M: 51.8 SD: 16.4 17–100 55.4% | According to Poisson regression, age, marital status, education and employment status were not significantly related to the number of physician visits. | The logarithmized equivalent income remained insignificant. | The number of physician visits was positively associated with decreased self-rated health (ß = 0.40, p < 0.001) and being severely disabled (ß = 0.18, p < 0.001). | An external locus of control was positively correlated with higher levels of physician visits (ß = 0.00, p < 0.05). Internal locus of control was not significant. |

| Hajek (2017b) [16] | Germany | Number of GP visits, specialist visits and having had a hospital stay during the last twelve months | Two waves from 2008 to 2011 | German Ageing Survey | n = 1372 M: 64.3 SD: 11.2 40–95 52.2% | Regarding fixed-effects regression, being retired (ß = 0.17, p < 0.05) or not employed (ß = 0.18, p < 0.05) was related to more physician visits. A higher age was associated with a having a hospital stay (OR: 0.91, 95% CI: 0.84–0.98), as well as not being employed (OR: 2.37, 95% CI: 1.01–5.56). Marital status remained insignificant. | Logarithmized equivalent income and self-rated accessibility of doctors were not significant predictors. | Self-rated health was associated with all GP visits (ß = 0.11, p < 0.001), specialist visits (ß = 0.20, p < 0.001) and a hospital stay (OR: 1.77, OR: 1.34–2.32). The number of chronic diseases was related to more GP visits (ß = 0.04, p < 0.01) and specialist visits (ß = 0.06, p < 0.01). Overweight (ß = −0.16, p < 0.05) and obesity (ß = 0.24, p < 0.05) were related to a lower number of specialist visits. Underweight, currently smoking and physical activity remained insignificant. | Not applicable |

| Hajek (2018) [18] | Germany | Number of GP visits and specialist visits during the last three months | Two waves during a ten-month period | AgeQualiDe | n = 861 M: 89.0 SD: 2.9 85–100 69.0% | Poisson fixed-effects regression did not detect age or marital status as significant correlates. | Social network was not significantly correlated with GP visits. | Increasing cognitive impairment (ß = 0.17, p < 0.05) and increasing depressive symptoms (ß = 0.04, p < 0.1) were significantly related to GP visits, while functional impairment and the number of chronic conditions were not. | Not applicable |

| Hajek (2020) [17] | Germany | Having had a hospital visit during the last six months | Two waves during a ten-month period | AgeQualiDe | n = 861 M: 89.0 SD: 2.9 85–100 69.0% | According to random-effects regression, age, sex and marital status were not associated with hospitalization. | A higher social network (OR: 1.15, 95% CI: 1.06–1.25) was associated with a higher likelihood of hospitalization. Education remained insignificant. | A higher number of chronic conditions (OR: 1.06, 95% CI: 1.02–1.10) and increased depressive symptoms (OR: 1.11, 95% CI: 1.05–1.18) were significantly related to hospitalization. Moreover, the interaction between social network and functioning (OR: 0.98, 95% CI: 0.97–0.99) was associated with hospitalization.Cognitive impairment and functioning were not. | Not applicable |

| Kim (2016) [20] | South Korea | Any outpatient health services utilization during the last twelve months | Two waves from 2010 to 2012 | Korea Health Panel | n = 11,362 M: 51.1 SD: 17.8 57.1% | Respecting logistic regression, outpatient health services utilization was related to being female (OR: 3.12, p < 0.1), age (OR: 0.95, p < 0.05) and being married (OR: 8.3, p < 0.05). | Education, household income, economic activity and insurance were not related to outpatient health services use. | Having a chronic disease was correlated with service utilization (OR: 2.81, p < 0.05), but not with disability. | Not applicable |

| Stein (2000) [21] | United States | Having had a hospital visit or an outpatient visit during the last twelve months | Two waves from 1990 to 1991 | Homeless people living in Los Angeles County | n = 363 M: 38.1 18–70 30.0% | According to the pathway model, hospitalizations were significantly related to education (ß = −0.10, p < 0.05), being African American (ß = 0.09, p < 0.05) and drug use (ß = 0.13, p < 0.05). Ambulatory office visits were associated with alcohol problems (ß = −0.10, p < 0.05) and drug use (ß = 0.18, p < 0.01). Poor housing remained insignificant. | Having a place to go for health care was related to increased levels of ambulatory office visits (ß = 0.32, p < 0.001) and community support (ß = 0.10, p < 0.05). Hospitalizations were related to community support (ß = 0.10, p < 0.05) and barriers (ß = 0.17, p < 0.001). Health insurance and social support were not significant predictors. | Having a poor health was related both to ambulatory office visits (ß = 0.09, p < 0.05) and hospitalizations (ß = 0.12, p < 0.05). Psychotics and depression remained insignificant. | Not applicable |

| First Author (year) | Study Objective | Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria | HCU Description | Comparison Group or Disorder-Specific HCU | Data Source | Missing Data | Statistics | Consideration of Confounders | Sensitivity Analysis | Sample Size (Subgroup) | Demographics | Results Discussed with Respect to Other Studies | Results Discussed Regarding Generalizability | Limitations | Conclusion Supported by Data | Conflict of Interest/Funders | % of Criteria Fulfilled by Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al Snih (2006) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 87.5 |

| Clay (2011) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 93.8 |

| Gabet (2019) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 93.8 |

| Hadwiger (2019) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 93.8 |

| Hajek (2017a) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 93.8 |

| Hajek (2017b) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 93.8 |

| Hajek (2018) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 93.8 |

| Hajek (2020) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 93.8 |

| Kim (2016) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 87.5 |

| Stein (2000) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 93.8 |

| % of criteria fulfilled by studies | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 30 | 100 | 100 | 50 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 92.5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hajek, A.; Kretzler, B.; König, H.-H. Determinants of Healthcare Use Based on the Andersen Model: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9101354

Hajek A, Kretzler B, König H-H. Determinants of Healthcare Use Based on the Andersen Model: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Healthcare. 2021; 9(10):1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9101354

Chicago/Turabian StyleHajek, André, Benedikt Kretzler, and Hans-Helmut König. 2021. "Determinants of Healthcare Use Based on the Andersen Model: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies" Healthcare 9, no. 10: 1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9101354

APA StyleHajek, A., Kretzler, B., & König, H.-H. (2021). Determinants of Healthcare Use Based on the Andersen Model: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. Healthcare, 9(10), 1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9101354