Impact of Nurse-Patient Relationship on Quality of Care and Patient Autonomy in Decision-Making

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. Role of the Patient

2.2. Role of the Nurse

2.3. Types of Nurse-Patient Relationships

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Sample/Participants

3.2.1. Nursing Records

3.2.2. Interviews with Nurses

3.3. Data Collection

3.3.1. Nursing Records

3.3.2. Interviews with Nurses

3.4. Ethical Considerations

3.5. Data Analysis

3.5.1. Validity and Reliability/Rigour

3.5.2. About the Nursing Records

3.5.3. About Interviews with Nurses

3.6. Research Limitations

4. Results

4.1. Nursing Records in Clinical Histories

4.2. Nurses Interviewed

5. Discussion

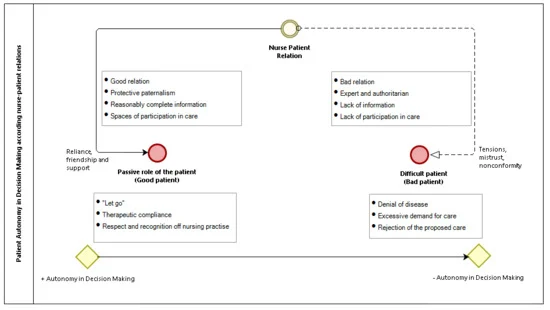

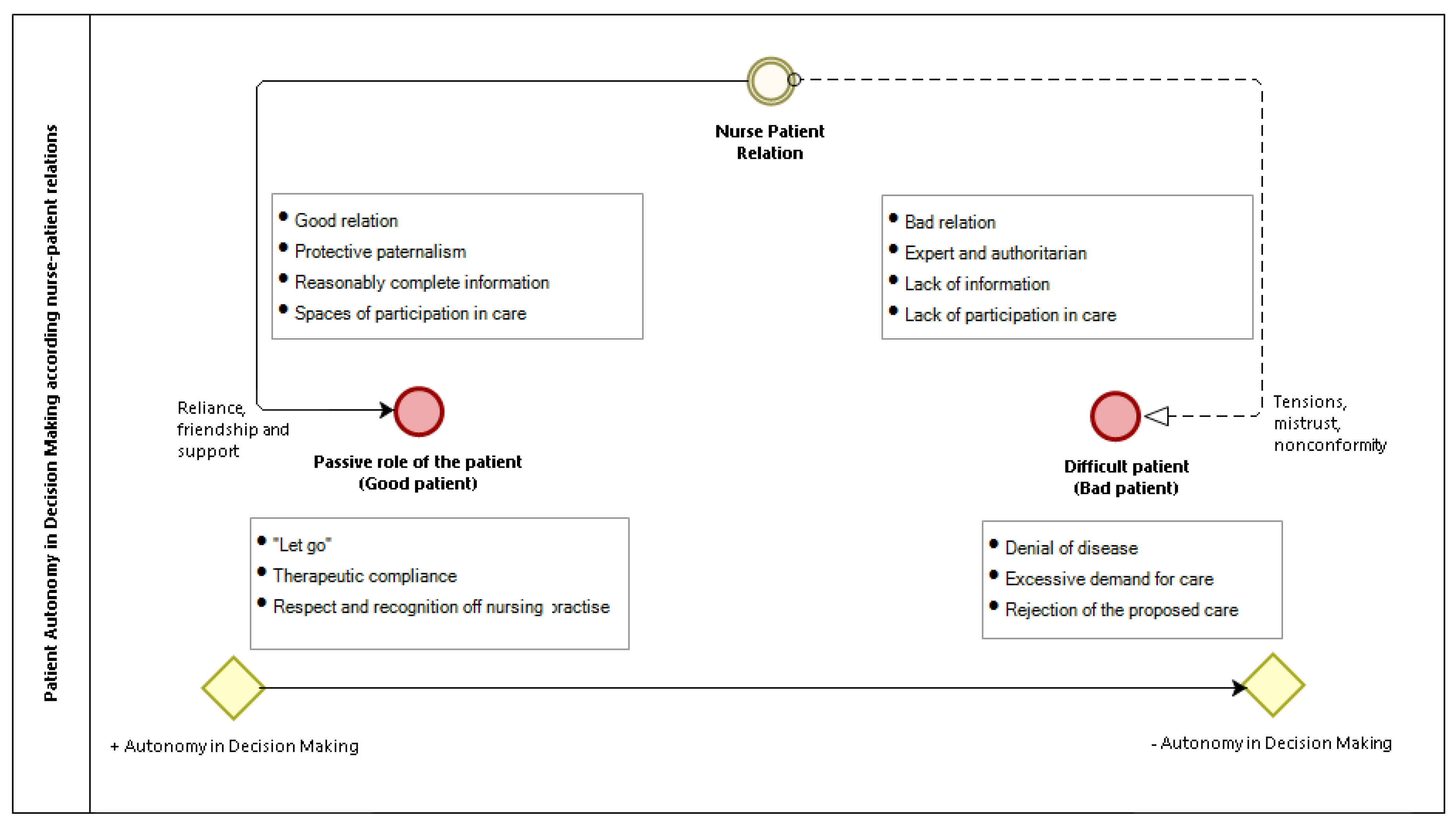

5.1. Autonomy in the Decision-Making of the Patient According to the Relationship with the Nurse

5.2. Perception about the Patient

5.3. Nurse-Patient Relationship

6. Conclusions

- Contribution of the Paper

- What is already known about the topic?

- -

- Analysing the type of relationship of the nurse with the patient allows establishing strategies to improve the quality of care and the degree of satisfaction of both.

- -

- Knowing the impact of the nurse-patient relationship on the autonomy of patients allows to increase their capacity in decision-making.

- -

- Evidence of limitations in nurse-patient relationships leads to a change in the patient-centred healthcare model.

- What this paper adds?

- -

- Nursing records show an absence of the patient’s autonomy in decisions making about their care. In the interviews, it is evidenced in nurses of more experience and age, a greater degree of participation of the patients.

- -

- Nurses prefer a submissive patient, who assumes care without discussion and respecting the work of the nurse.

- -

- The patient is labelled, both in the nursing records and in the interviews, as a good or bad patient according to the relationship with the nurse.

- How should the findings be used to influence policy/practice/research/education?

- -

- Implementing new ways to understand the management of health organizations that favour the relationship between members of the healthcare team with the patient, improve the decision-making capacity of the patient in the clinical setting.

- -

- Promoting a good relationship between the nurse and the patient, based on real respect for their decisions, would lead to a less tense in the nurse practice and with fewer limitations in communication and autonomy of the patient.

- -

- Until now, the nursing records in the different studies had not provided information on the quality of care and patient autonomy. Although these are a complex source of information, its analysis can provide great richness in the written discourse of nurses.

- -

- According to the results obtained, the educational model of the nurses should be modified, directed more towards a patient-centered model.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hallet, C.E.; Austin, L.; Caress, A.; Luker, K.A. Community nurses’ perceptions of patient “compliance” in wound care: A discourse analysis. JAN 2000, 32, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeWolf Bosek, M.S.; Jannette, J.; Rambur, B. Attitudes of nurses toward patient-directed dying: A pilot study. JONA’s Healthc. Law Ethics Regul. 2013, 15, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, S.; McAllister, M.; Broadbent, M. The vital blend of clinical competence and compassion: How patients experience person-centred care. Contemp. Nurse 2015, 52, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahlberg, B. “No education about me without me”: A shared decision-making approach to patient education. Nursing 2015, 45, 15–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fellowes, D.; Wilkinson, S.; Moore, P. Entrenamiento en habilidades comunicativas para los profesionales con pacientes con cáncer, sus familias y cuidadores [Training in communication skills for professionals with cancer patients, their families and caregivers]. La Bibl. Cochrane Plus 2008, 2, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- George, T.P. How nurses can encourage shared decision making. Nursing 2013, 43, 65–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davison, I.; Cooke, S. How nurses’ attitudes and actions can influence shared care. J. Ren. Care 2015, 41, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gray, T.F. How Can I Change My Patients’ Treatment Decision Making by Becoming a Nurse Scientist? Clin. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2017, 21, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griscti, O.; Aston, M.; Warner, G.; Martin-Misener, R.; McLeod, D. Power and resistance within the hospital’s hierarchical system: The experiences of chronically ill patients. J. Clin. Nurs. 2017, 26, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sherner, T. Making Treatment Decisions Together. ONS Connect 2016, 31, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill, J. Patient participation: A review of the literature. JAN 1998, 7, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truglio-Londrigan, M. The Patient Experience with Shared Decision Making: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. J. Infus. Nurs. 2015, 38, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arroyo-Arellano, F. La Investigación y la bioética. [Research and Bioethics], 1st ed.; Edimec: Quito, Ecuador, 2014; pp. 34–212. [Google Scholar]

- Kleiman, S.; Frederickson, K.; Lundy, T. Using an electric model to educate students about cultural influences on the nurse-patient relationship. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2004, 25, 249–253. [Google Scholar]

- Grffith, R.; Tengnah, C. Shared decision-making: Nurses must respect autonomy over paternalism. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2013, 18, 303–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, G. Nurses are best placed to ensure the ethical application of DNRs. Nurs. Etand 2016, 30, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, R. Understanding the Code: Acting in a patient’s best interests. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2015, 20, 458–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahlberg, B.; Foronda, C.; Baptiste, D. Cultural humility: The key to patient/family partnerships for making difficult decisions. Nursing 2016, 46, 14–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, S. Power imbalance between nurses and patients: A potential inhibitor of partnership in care. J. Clin. Nurs. 2003, 12, 501–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaquin-Pavan, É. Is nursing care an intrusion? Soins 2015, 794, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, B. Countering the stereotype of the unpopular patient. Nurs. Older People 2013, 25, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, J.; Titchen, A. Practice Knowledge and Expertise in the Health Professions, 1st ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A. Implications of patient shared decision-making on wound care. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2013, 18, S26–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolovos, P.; Kaitelidou, D.; Lemonidou, C.; Sachlas, A.; Sourtzi, P. Patient Participation in Decision Making During Nursing Care in Greece—A Comparative Study. Nurs. Forum 2015, 50, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, L. Introducing the patient’s choice. Nurs. Stand. 2014, 28, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito, L. The effects of medication education in adherence to medication regimens in an elderly population. JAN 1995, 21, 935–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, K.N. Compliance or collaboration? The meaning for the patient. Nurs. Ethics 1995, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinker, M. The current status of compliance. ERR 1997, 8, 235–238. [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann, W.F. Adherence: A matter of self-efficacy and power. JAN 1997, 26, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroudy, D. Should we tell the truth to patients? Soins 2014, 789, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, C. Patient compliance: Recognition of factors involved and suggestions for promoting compliance with therapeutic regimens. JAN 1996, 24, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, S.R.; Rego, G.; Nunes, R. Right or duty of information: A Habermasian perspective. Nurs. Ethics 2016, 23, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadow, S.L. Defining the doula’s role: Fostering relational autonomy. Health Expect 2015, 18, 3057–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, C.; Wellard, S.; Mummery, J. Problematising autonomy and advocacy in nursing. Nurs. Ethics 2014, 21, 576–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luker, K.A.; Austin, L.; Caress, A.; Hallet, C.E. The importance od “Knowing the patient nurses” construction of quality in providing palliative care. JAN 2000, 31, 775–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appelin, G.; Bertero, C. Patients’ experiences of palliative care in the home: A phenomenological study of a swedish sample. Cancer Nurs. 2004, 27, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusk, J.M.; Fater, K. A concept analysis of patient-centered care. Nurs. Forum 2013, 48, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oudshoorn, A.; Ward-Griffin, C.; McWilliam, C. Client-nurse relationship in home-abased palliative care: A critical analysis of power relations. J. Clin. Nurs. 2007, 16, 1435–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, M.; Zamanzadeh, V.; Valizadeh, L.; Khajehgoodari, M. Assessment of nurse-patient communication and patient satisfaction from nursing care. Nurs. Open 2019, 6, 1189–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karaca, A.; Zehra, D. Patient satisfaction with the quality of nursing care. Nurs. Open 2019, 6, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aiken, L.H.; Cerón, C.; Simonetti, M.; Lake, E.T.; Galiano, A.; Garbarini, A.; Soto, P.; Bravo, D.; Smith, H.L. Hospital nurses staffing and patient outcomes. Rev. méd. Clín. Las Condes. 2018, 29, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, P.; Müggenburg, C. Personal relationships among between the nurse and the patient. Enf. Univ. 2015, 12, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Foucault, M. «La incorporación del hospital en la tecnología moderna». Conferencia de 1974 en la universidad de Río de Janeiro. Rev. Centroam. de C.S. 1978, p. 6. Available online: http://hist.library.paho.org/Spanish/EMS/4931.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2020).

- Holmes, D.; Gastaldo, D. Nursing as means of governmentality. JAN 2002, 38, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foucault, M. Historia de la Sexualidad. la Voluntad del Saber, 30th ed.; Siglo XXI: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. The Hermeneutics of the Subject. Lectures at the College de France 1981–1982, 1st ed.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 198–227. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M.; Rabinow, P. Politics and Ethics: An Interview. The Foucault Reader. An Introduction to Foucault’s Thought; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Bartol, T. Responding to criticism: A choice to grow. J. Nurse. Pract. 2016, 41, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gafni, A.; Charles, C. The physician–patient encounter: An agency relationship. In Shared Decision-making in Healthcare: Achieving Evidence-based Patient Choice, 2nd ed.; Edwards, A., Elwyn, G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Cribb, A.; Entwistle, M.A. Shared decisión making: Trade-offs between narrower and broader conceptions. Health Expect 2011, 14, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Entwistle, V.A.; Carter, S.A.; Cribb, A. McCaffery, KSupporting patient autonomy: The importance of clinician-patient relationship. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2010, 25, 471–475. [Google Scholar]

- Duke, G.; Yarbrough, S.; Pang, K. The patient self-determination, act: 20 years revisited. J. Nurs. Law 2009, 13, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calloway, S.J. The effect of culture on beliefs related to autonomy and informed consentc. J. Cult. Divers. 2009, 16, 68–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, A. Relational autonomy or undue pressure? Family’s role in medical decision-making. Scand. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2008, 22, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, R.M.; Peters, E. Beyond information: Exploring patients preferences. JAMA 2009, 302, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, W.L.; Han, P.K.J.; Fagerlin, A.; Stefanek, M.; Ubel, P.A. Rethinking the objectives of decision-aids: A call for conceptual clarity. Med. Decis. Making 2007, 27, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevdalis, N.; Harvey, N. Predicting preferences: A neglected aspect of shared decision-making. Health Expect 2006, 9, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowie, J. The role of patients_ meta-preferences in the design and evaluation of decision-support systems. Health Expect 2002, 5, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Emmanuel, E.J.; Emmanuel, L.L. Four models of the physician–patient relationship. JAMA 1992, 267, 2221–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.C. The nurse-apatient relationship: Theme and variations. JAN 1992, 17, 496–506. [Google Scholar]

- Guarinoni, M.G.; Dignani, L.; Motta, P.C. Shared decision making: A scoping review. Prof. Inferm 2016, 69, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N Records | Months | Nursing Records in Inclusion Criteria | Nursing Records in Exclusion Criteria | Total Selected in Phase I | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experience > 3 years | Hospitalization > 5 days | Experience < 3 years | Hospitalization < 5 days | |||

| 9103 | January 2015 | 9103 | 9103 | 0 | 0 | 9103 |

| 8037 | February 2015 | 8037 | 8037 | 0 | 0 | 8037 |

| 8820 | March 2015 | 8820 | 8820 | 0 | 0 | 8820 |

| 8821 | April 2015 | 8821 | 8821 | 0 | 0 | 8821 |

| 7906 | May 2015 | 3912 | 3912 | 3221 * | 773 ** | 3912 |

| 11744 | June 2015 | 856 | 856 | 7233 * | 3655 ** | 856 |

| 13929 | July 2015 | 774 | 774 | 4899 * | 8256 ** | 774 |

| 11192 | August 2015 | 308 | 308 | 1006 * | 9878 ** | 308 |

| 9962 | September 2015 | 2521 | 2521 | 5623 * | 1235 ** | 2521 |

| 10996 | October 2015 | 6987 | 6987 | 3210 * | 789 ** | 6987 |

| 9379 | November 2015 | 7036 | 7036 | 1211 * | 566 ** | 7036 |

| 11204 | December 2015 | 4309 | 4309 | 6253 * | 321 ** | 4309 |

| Subtotal | 61.484 | 32.656 | 25.473 | |||

| Total | 61484 | |||||

| Nurse | Age | Unit | Professional Experience in Years | Years in Units | Labour Situation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | 37 | EME * | 11 | 5 | Permanent staff |

| E2 | 29 | EME | 9 | 6 | Eventual staff |

| E3 | 34 | MIR ** | 13 | 5 | Eventual staff |

| E4 | 50 | EME | 28 | 19 | Permanent staff |

| E5 | 54 | EME | 17 | 24 | Permanent staff |

| E6 | 39 | EME | 18 | 6 | Permanent staff |

| E7 | 35 | MIR | 12 | 3 | Eventual staff |

| E8 | 37 | MIR | 10 | 3 | Eventual staff |

| E9 | 45 | MIR | 12 | 7 | Eventual staff |

| E10 | 31 | MIR | 9 | 5 | Eventual staff |

| E11 | 37 | MIR | 9 | 5 | Eventual staff |

| E12 | 28 | EME | 7 | 3 | Eventual staff |

| E13 | 31 | MIR | 9 | 5 | Eventual staff |

| Element | Transcription |

|---|---|

| Silence > 3 s | (Silence) |

| Silence < 3 s | |

| Laugh | (Laugh) |

| Laughter interviewer, interviewee, and observer | (All laugh) |

| Tails | Literal transcription |

| Doubtful attitude | (doubt) |

| Category: Be Patient | ||

|---|---|---|

| Code | Definition | Nursing Records |

| Good patient from nurse’s perspective | In an impersonal way, clinical states, vital signs and pathologies are recorded, wherein the identity of the patient disappears. The nurse gives importance to purely clinical aspects and, in some cases, to moods, as long as they relevantly impact the patient’s well-being. | Sv (urinary catheter) carrier, peripheral venous, and oxygen therapy. Patient … a little anxious and nervous, stable constants, peripheral venous (18 msi (left upper arm)). Maintains stable constants the rest of the afternoon. Upon arrival at the plant: Arterial hypertension, norm-cardiac and maintenance of good saturation, conscious and oriented. Autonomous patient for basic activities of daily life. Not demanding and very consistent. |

| The patient’s voice appears as a mere expression of pain or subjective perceptions about clinical processes, which provide information to the nurse about how he/she feels or is concerned. This attitude is not related to the fact that the patient acquires real autonomy in the care. The nurse calls the patient a collaborator and participant, as long as he respects and assumes the marked therapeutic indications. | Patient very collaborative and participative in her care. Asymptomatic. Collaborating patient. She goes to the shower to showers self very well. Patient very cooperative and committed to his/her TTº (treatment). | |

| Bad patient from nurse’s perspective | Nurse prefers what she calls a clean field, without a patient who causes problems. The dominant term coined by the nurse to refer to this type of patients is “demanding” or, with more emphasis, “very demanding”. This would be the first indication that alerts the nurse that these patients will require more attention, in terms of workload, and that there is thus a need to understand the negative aspects. These records may be interpreted as warnings to other nurses, so that they initiate preventive coping strategies such as patience, assertiveness or any other skills that might be useful to them, including the use of pharmacological measures of containment. It has been observed that cataloguing a patient as “demanding” indicates a hidden discourse, which seems to be understood by other professionals, since there is no reference in the records to the type of demands that arise. It can only be verified that patients are “demanding” because they continuously access the nursing control, require certain care, and request too much information when the demands are considered of little importance, especially during the night shift. | Patient very negative to the treatment that is being given. Patient is very demanding and continually asks for removal of the nasogastric probe. At the beginning of the night very demanding, so, it was deemed necessary to change the roommate for his rest of the night. Patient asking for sleeping pill, demanding, asking for things but not disoriented … Calls constantly to say that it is uncomfortable, that we do not turn off the light, that the room is disorderly, that we incorporate it again, that he has swollen legs, … Attended to each time and given warning. Call uninterrupted throughout the night. |

| The next warning sign is a patient who becomes not only “demanding” but also difficult and even annoying. This more radical perception is confirmed through records of the patient’s denials of treatments and imposition of nursing care. The situations are described in which the nurse and doctor use strategies of persuasion and/or coercion with the objective that the patient follows the orders of the professionals. The dominant need to carry out these imperatives is justified by clinical criteria, patient well-being and survival. In cases in which patients disagree about the care provided, a range of tensions open up with the nurse and the other involved professionals. Thus, an attitude of dialogue with the patient is evidenced by the nurse to resolve such situations of stress, particularly in the case of failure, for which the recourse is containment measures with the intervention of the doctor. | I am going to administer paracetamol according to the guidelines, and the patient refuses. I comment to the guardian doctor who returns to speak with the patient, who again consents. I tell the patient that it is necessary to channel a new venous line … the patient refuses to do so and requires me to recanalize it and heal the venous line. By telling him that I will not act as he tells me, since I do not consider it prudent, the venous line is started. The patient tells me that I should take the venous line "the first time". I comment with my partner who offers to channel that way to soften the situation. I am surprised that after administering the sprays he was going to administer the Salbutamol and Atrovent inhalers he has in his desk drawer on his own, and I inform him that he will ONLY be administered what we give him The patient refers on several occasions that she has not been given the medication … I mention that in the nursing folder, both are administered. I show him the signatures because he does not believe it. He reproaches me on several occasions that we have changed the medication schedule … I comment with the GD on all the demands and demands of the patient. He insists that the doctor come and finally calls the physician. The patient does not obey the treatment prescribed by the doctor, nor does he pay attention to the nursing advice. | |

| There appears a third concept of patients that is perceived by the nurse as an increase in their workload and that requires a lot of care. This is a patient who is qualified as agitated or disoriented with neurological alterations. In this case, the agitation usually involves the application of pharmacological treatments and mechanical restraint. The use of these measures is justified as patient safety and the avoidance of traction of sanitary devices, especially invasive ones. In extreme situations, the patient is isolated in a room. | In the morning, the patient escapes through the emergency door, and security is called, and the patient is found in the cafeteria bathroom. It is necessary to mechanically restrain the patient in the room. Uneasy patient in the early afternoon, becomes aggressive, and does not want to go to the room, requiring staff reinforcement to put him in bed. I speak with the doctor on duty, who decides to isolate the patient because of a social problem. Uneasy patient in the morning, agitated and aggressive, requiring the help of Dr. XX to administer 1 ampoule of Haloperidol IM, which is effective. Accurate mechanical restraint because the patient was pulling the bed. | |

| Patients with social problems * from the nurse’s perspective | The dependent patient refers to one who has a loss of autonomy for carrying out activities of daily living due to mobility problems or in situations such as dementia, respiratory problems, and very reduced levels of consciousness. | Inspiring by mouth, I tell him to perform breathing exercises by inhaling through the nose and exhaling through the mouth, although the patient fails to perform them. I try to sit him in the chair, but he does not have any strength in his legs. |

| The patient catalogued as a social problem is recorded many times in relation to the absence of a social-family network. These patients are sometimes considered problematic and require extraordinary measures such as confinement to isolated rooms due to discomfort to other patients, or transfer to residences. | No family or friends, pending social services. Social problem. According to the emergency report, the woman remains hospitalized because it seems to be a social problem, she lives alone and her few relatives have difficulties related to the care of the patient. | |

| Category: Patient as a Passive Object of Care | ||

|---|---|---|

| Code | Definition | Interviews |

| Protective paternalism with the patient | It is noted that the nurse acts as a consultant to the patient, taking the doctor as a reference. The nurse bases her relationship with patients on trust and friendship to calm their anxieties and worries during the hospital stay. The nurse prefers a relationship, in the absence of conflicts with the patient, providing security and using a basic language, low cultural level, and understandable. This is directly related to a protective paternalistic attitude and the consideration that the patient does not have sufficient knowledge to understand medical language. | I1: “I think my relationship with the patient is good because I try to be there as much as possible and with the family so I can provide them the option to talk to me about anything they want, if they have any doubts, I try to solve all the doubts they have. And if I do not know how to refer them to another […] I think that more as a consultant because I´m not an expert. I always believe that the most expert person is the physician, so I am like an aide” I3: “Our role is to advise and provide confidence to be able to be calm and resolve all, (…) and well, to provide their peace while they are in the hospital, which creates numerous anxieties” I10: “[…] If you are explaining anything or whatever it is he can understand (…) at his level, you must speak at the level that he understands” |

| Empathy appears in discourse as a fundamental aspect of the relationship with the patient. The nurse believes that having a good relationship should involve understanding the patient at all times. When that level of understanding is reached, the relationship improves. Younger and less experienced nurses do not recognize the limitations in regard to empathizing with the patient. Collaboration in care is considered sufficient for the patient to exercise his/her power of decision. In the case of nurses with more professional experience, greater sensitivity is indicated by the autonomy of the patient, trying to adapt the information provided to them so that they decide on some strategies for their care. | I2: “Have empathy. For me, this is fundamental. I think that in order to have a good relationship with the patient, I have to understand… But as soon as I understand them, as soon as I start talking to them, I understand them a bit; and that’s when the relationship always improves” I3: “Well, an open, cordial, close and empathetic relationship … Yes, yes, it’s friendly, and it allows the possibility to understand the patient as much as possible” | |

| Tensions in nurse-patient relationships | It dominates a discourse where the nurse attributes tensions to the patient’s attitude towards illness or discontent or denial care provided. The lack of acceptance by the patient about his/her illness is the main source of conflict and is increased in the presence of an aggressive attitude of the patient or lack of respect for the nurse practice. This statement is what occurs in most speeches from the perspective of the nurse, being the cause of the lack of acceptance. | I3: “…(…) she asked us for pyjamas, and we told her that we were busy (…) she placed herself in the middle of the hall and told us that we were uncool and well, we told her we did not refuse but, we just said wait a little because we are busy with another patient” I6: “The aggressiveness that the patient may have. That is, that above all they have an illness, which may lead to verbal or physical aggression towards you, so you try to perform in good faith. So, what I do not do, now I filter it more, but I do not like when they shout at me. Then, bad education or the one who shouts at me takes it fatally. Go, like (laughs) but when you stop screaming I’ll be back, and I’m leaving … I mean, you’re sick, but you’re not disabled” |

| In the face of conflict situations, a minority sector considers a patient’s resistant attitude to the imposed care to become a challenge, so that a series of skills must be displayed to maintain a good relationship with him. There is consensus that the patient’s denial of the proposed care generates a series of strategies of persuasion and coercion and consequently a clear limitation in the patient’s autonomy to make decisions. | I4: “These patients, the ones that make it difficult to work, are like a challenge, and we have to be even better” I8: “For example, he refuses to do a test (…) then you insist and sometimes he screams at you, (…) you are seeing that it is important for him and you insist” I13: “And it is a test that he or she needs and refuses to do, and you have to be convinced and then of course, at one time, another, another and another because if there is a conflict in the end, you perform badly, do you not? You no longer work at ease like you want because he does not allow himself to try to solve his problem” | |

| Older nurses with more professional experience not only refer to the attitude of patients as causes of stress but also consider the nurse to be responsible for the conflict due a lack of communication skills, especially empathy. | I2: “When I perform poorly with patients, it is when I do not understand them. For patients like these, I say, what’s wrong? What is going on in his head to be pissed, angry …? Then, the relationship is already bad” | |

| Patient decision power | There is evidence, on the one hand, of a passive role of the patient as an object of care and, on the other hand, an active role that at its extreme is considered a difficult patient. These roles determine the ability of patients to make decisions. A patient who trusts the nurse and therefore does not make decisions and "lets go" defines the passive role. It is noted that once the patient enters the hospital, he is considered to be the property of the institution and professionals. It is expected of him to assume the rules and norms and to take care of taxes, without considering previous information. Therefore, the patient’s autonomy capacity, in this case, is limited to following the recommendations of the professionals and the institution. This limitation increases according to the low level of physical autonomy and age, and this dependence is confused with the ability to make decisions. It is observed that, to provide some information to the patient about what will be done to him, it is sufficient to cover the needs of autonomy. In younger and less experienced nurses, there is a resistance to provide information to the patient, and if it occurs, it reduces workloads. In contrast, in older nurses and more professional experience, the need to report is present in almost all cases. | I2: “I believe that patients are left to carry a lot for us. They do not assume much prominence in their care, I think. They get carried away by us … everything we tell them is what they believe. If we say that the pain comes from there, they believe it and it is already…” I4: “I cannot say that they make the decisions because we are always following the guidelines, although I think we have to make them part of why we do this or that” |

| The patient who does not acquire the role of submission and performs different activities marked by the institution or those considered by the professionals should be assumed by the patient, configures a pro-active and emergent role. The nurse qualifies as a demanding patient. Demanding patients are patients who refuse to perform certain tests, refuse treatment or make their own decisions, and demand too much information. This type of patient is perceived by the nurse as a bad patient who does not accept their situation. In contrast, there is a sector of nurses who try to provide a more active role for the patient, as long as it does not generate conflicts or strongly deny the proposed care. | I1: “There are patients who, for whatever reason, are more difficult to treat or believe that they are not sick and in fact are then because they work with more difficulty because they do not want the treatment that they are getting, or they do not understand why they are receiving it” I2: “It is not the same going to heal a patient who makes it easy for you, who is nice, who understands you, who helps you compared with another patient who is not, who is moving, who is talking on the phone while you are healing…” I4: “There are people who do not get much care because they seem to regress to babies…” | |

| Finally, it is emphasized that the non-acceptance of the disease causes in the patient non-conformist attitudes towards care. This attitude is sometimes perceived by the nurse as aggression. In these cases, the patient is qualified as difficult or uncomfortable with an attitude of disrespect, increasing the workload of the nurse. | I7: “He does not understand that there are thirty-one more patients out there, right? Then, he only understands that he has been uncomfortable for ten minutes, and sometimes you get stressed and you get there. He responds that you do not accept what I say because you have not been standing with your arms crossed doing nothing… and you can answer wrongly. And of course, that happens” | |

| Nurse’s power strategies | Three roles of the nurse with respect to the relationship with the patient stand out and determine the decision-making power of the patient. In the first place, there is evidence of a marked maternalistic attitude of the nurse. This maternalism, or protective paternalism, highlights the limitations of knowledge and skills of nurses in clinical situations, which are replaced by humane treatment with the patient, which is especially prominent in older nurses and those with more professional experience. These nurses are more comfortable being a support for the patient, basing their relationship on trust, friendship, and closeness. The nurse assumes that the patient considers her as the professional who can express her feelings. Care is defined as an art, and constant communication with the patient about issues unrelated to their illness is defended. | I1: “An I expert I am not (…) Well I think he sees me as a point of support for … Like him, when he is here in the hospital, he is sick because he must rely on someone to help him solve his doubts … and you give the patient some confidence because if they do not have that trust, they will not talk to you and they will not feel well” I4: “I am very affectionate, I like caring a lot and also placing a little distance … I try to treat the patient with respect and to not treat them as silly, sick, sick people who seem to understand nothing and I start talking to everyone about You who also … you know? And then with time, well, I do not know, with some people evidently, because they become better, others become worse…” I8: “Throughout the duration, the longer period of time, for example the patient, is admitted, it is a perception of mine that he experiences a trust more as friendship and does not have as much need for you … I feel comfortable, being, therefore affectionate when you have to be, being a professional when you have to be” |

| Second, an attitude of an expert nurse is observed only when activities delegated by the doctor are assumed. This role is associated with technical skills and clinical knowledge and is determined by pre-established protocols to ensure the adequacy of the provided care. This group of nurses believes that the patient does not have the capacity to make decisions because they do not know the scientific evidence, so the information is reduced to banal issues. However, in addition, these nurses prioritize techniques on any other aspect. | I4: “There are already some protocols, but sometimes you have to change them; we are doing all the same …” I6: “Let’s see if he understands that you are there, that you are a professional, that you are the nurse, yes, but that you are also the person that at any given moment can solve any doubt that he has … you introduce yourself and you already are neither the young lady, nor the lady, nor the nurse, you are so-and-so, that you are such and that you are working this turn, then he has reference, he or she, well” | |

| The nurse sees herself as the physician’s link to the patient, and although it is an assumed role, situations are described in which the lack of communication between professionals provokes tensions with the patient. It is noted that the nurse defends plots of professional autonomy and tries to prevent the patient from seeing her as an assistant to the doctor. The perception that as a nurse you have a lack of professional autonomy, can cause tense interprofessional relationships, which affects the ability to make decisions to patients, due to lack of information or reproaches to the work of other professionals. | I1: “The doctor is there five minutes a day, I’m there for a whole shift, of course, and the patients do not say practically anything with the doctor, and with us they can talk… Then, I can get some information that I can relay to the doctor the next day or leave written on the computer, which the doctor can read and use to mitigate the patient’s doubts” I7: “…because sometimes the patient knows things that we do not know, and we are unprofessional because sometimes I enter a room and the patient says is going to do this test, and I did not know and, of course, you are very wrong” | |

| Be a good patient from the nurse’s perspective | Being a "good patient" from the nurse’s perspective is defined by a patient without identity, trusting, without information, and grateful, i.e., a submissive patient, passive object of care, and without decision power. | I2: “The patient who assumes a lot of his illness. There are patients who assume it, but there are people who are in continuous denial, and I think those are the bad ones. For me” I2: “Patients who want too much care or who feel too dependent or who believe, as we say, they are in a hotel … Come on, we have to be for them constantly, I think that is when I have more difficulties with patients, when they demand too much attention” I9: “…The one who helps, the one who has, just as I want to have empathy with them, the one who has empathy also with the nurse, the one who values our work, the one who… those who have patience with us” |

| It is evident that the nurse prefers a patient who follows the guidelines and who does not ask for many explanations about the provided care. In brief, the patient does not carry out their own initiatives. | I5: “…the patients are now no longer like they used to be, they want explanations for everything. They want you to explain everything you are going to do to them, what you are going to do to them, are they always waiting when you enter first, what are you going to do to me?” I12: “We want a field too clean to be able to work, right? Without problems …” | |

| Impact of the nurse-patient relationship in care | It is observed that the good relationship with the patient improves general care. The improvement is the key of more dedication, confidence, security, empathy, and assertiveness. It is also emphasized that with a good relationship, the patient is calm and experiences an improved emotional state and that better healing results are obtained. | I2: “You go to a patient who gets along well or who understands you and all that and you help him with desire… Well, you treat him the same, do you not? (Laughs) but you go as more predisposed, you spend more time, you listen to him more, you spend more time with him and in the end, and in the end, these patients are the ones that receive more attention than those who are demanding” I7: “If you have a good relationship and have provided confidence to the patient, kindness and he feels safe, the night is a good time” |

| It is noted that a poor relationship with the patient causes poor communication, which is diminished by the patient’s concerns and care, less time spent, and patient dissatisfaction. Although it is recognized that the technical aspect of care is the same, the interaction with the patient changes. | I2: “If the relationship is bad, I think the care is not the same. It’s not bad, but you do not take care of it because a bad thing does receive as much care or you do not pay as much attention” I8: “That a patient who refuses everything, a patient who does not want what you propose, a patient who you then have to change the care, and maybe they are already undergoing another kind of care” | |

| A discourse of professional excellence emerges, in which the nurse refuses to associate a bad relationship with the patient with collateral effects on care. | I4: “I try to be exquisite in my care, and whether I have a bad relationship or whether it is good, as if it is … No, no, no, no. In contrast, sometimes I say that these patients, the ones that make it difficult to perform your job, like a challenge, and we have to be even better” | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Molina-Mula, J.; Gallo-Estrada, J. Impact of Nurse-Patient Relationship on Quality of Care and Patient Autonomy in Decision-Making. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030835

Molina-Mula J, Gallo-Estrada J. Impact of Nurse-Patient Relationship on Quality of Care and Patient Autonomy in Decision-Making. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(3):835. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030835

Chicago/Turabian StyleMolina-Mula, Jesús, and Julia Gallo-Estrada. 2020. "Impact of Nurse-Patient Relationship on Quality of Care and Patient Autonomy in Decision-Making" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 3: 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030835

APA StyleMolina-Mula, J., & Gallo-Estrada, J. (2020). Impact of Nurse-Patient Relationship on Quality of Care and Patient Autonomy in Decision-Making. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 835. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17030835