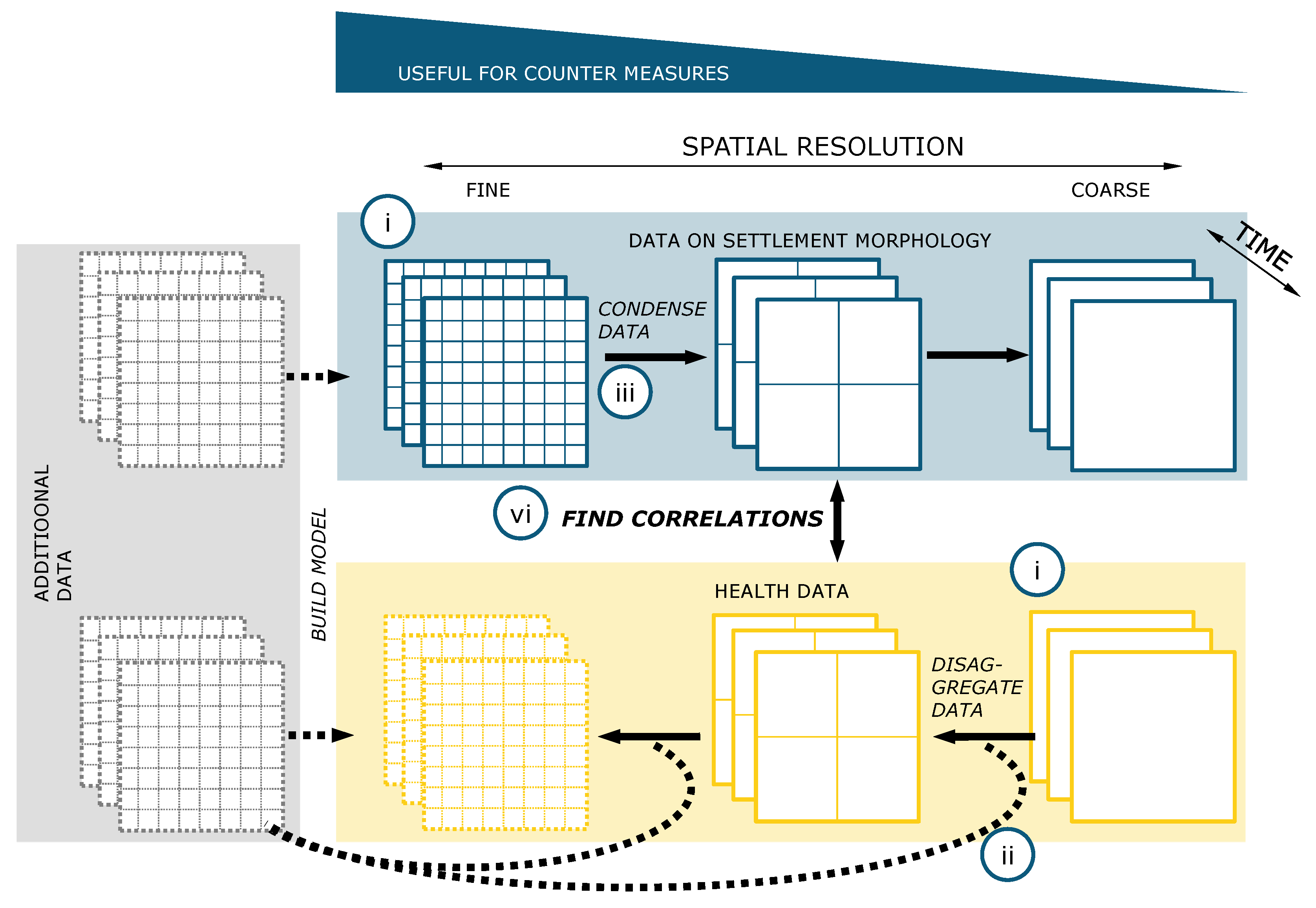

In the following, we first compile current information about slums and their identification. Thereafter, we present the results of a review, examining the latest publications on slums and informal settlements in PubMed. On the basis of this literature review, we discuss how and on which scales it is possible to investigate the relationship between health data and information on settlement morphology.

2.1. Information on Space

There are many different names for settlements of the urban poor. The most common terms are “slum” or “informal settlement”, but there are also local specific names in different parts of the world, such as “favela”, “barrio”, “shanty town”, “kampong”, amongst others [

23]. Although concrete images and conceptions are often associated with these names, exact quantitative definitions are not yet available [

23,

24,

25]. One definition frequently mentioned in publications is from the UN-Habitat, which describes households belonging to a slum meeting at least one of the following five criteria: non-durable housing, inadequate sanitation, unsafe water, insufficient living space, or insecure tenure [

1]. However, this definition has been criticized from a quantitative point of view, as it is not linked to measurable variables [

8]. From a qualitative point of view, the nomenclatures “slum”, “informal settlement”, and others have also been criticized, as they often have negative connotations [

23]. Therefore, they have been replaced in recent publications by more neutral terms, such as “deprivation areas” [

26].

Although the definitions can be criticized and discussed from many angles, the large number of existing studies shows that the urban poor often live in settlements that are morphologically different from their surroundings. The inhabitants of these settlements form a separate social group [

27] that is exposed to increased health risks [

2], and is associated with insufficient access to infrastructures such as sanitary facilities or water supply and inadequate housing situations. These settlements are often self-built and rarely recognized by the local or national governments [

5].

Basically, the aim is therefore to classify these spaces and describe their characteristics. Space can be characterized and classified according to Lilford et al. [

8] by surveys or by earth observation images. The advantages and disadvantages of the respective recording types have been discussed in detail in previous publications [

23,

28,

29]. With regard to slums, the use of earth observation data has especially established itself in recent years (cf. [

28,

29]), since the technical possibilities have expanded enormously. Kohli et al. [

30] studied slums and developed an ontology for slums for image classification using remote sensing data.

On the basis of this ontology, Wurm and Taubenböck [

27] have shown by comparing earth observation data and census surveys that a special settlement morphology represents a social group. They did an extensive review of the existent literature describing slums as a form of “arrival cities” [

31]. While surveys are time-consuming, information obtained by remote sensing can be analyzed very quickly and recent developments can be monitored. Furthermore, a high spatial resolution is possible (down to less than 1 m [

28]). The actually existing, physical conditions are mapped and no survey biases arise. However, remote sensing cannot provide any or only insufficient information about the condition of the sanitation supply or the connection to the water supply [

23]. Of the five dimensions in the above-mentioned UN definition, only one, non-durable housing, can therefore be covered.

However, recent studies in particular have shown that earth observation data can be used as a basis for recording settlements, which are then enriched with further geo-referenced data, e.g., from social networks or other data sources [

32,

33], to obtain more comprehensive information about these regions and in particular on their socioeconomic or health status [

9].

A problem here is that there is no uniform data collection in which all the available spatial information on slums is recorded, even though efforts to this end have been made [

34]. A desirable goal would be a kind of global dataset, similar to the “Global Urban Footprint”, on which the populated area was automatically recorded by Esch et al. [

35]. Comparable data can lead to global insights [

36], e.g., studies of eight different cities of the Global South show that slums have a similar size [

37,

38,

39]. Before this goal becomes tangible, however, a uniform definition of a slum must be established, which is still under discussion at present [

23].

It is clear that the focus should move away from the large known slums to the much more common small slums. Of course, only an automated process can provide this enormous scope. However, there are already approaches that can be used in the future. Aside from the discussion on the definition of slums, the focuses of recent publications are the temporal change of slums [

40,

41] and the adaption of machine-learning methods [

26,

40,

42,

43], which automatically record slums combining remote sensing data with other sources [

23]. Remote sensing datasets are also used to improve infrastructure planning for slums [

44,

45].

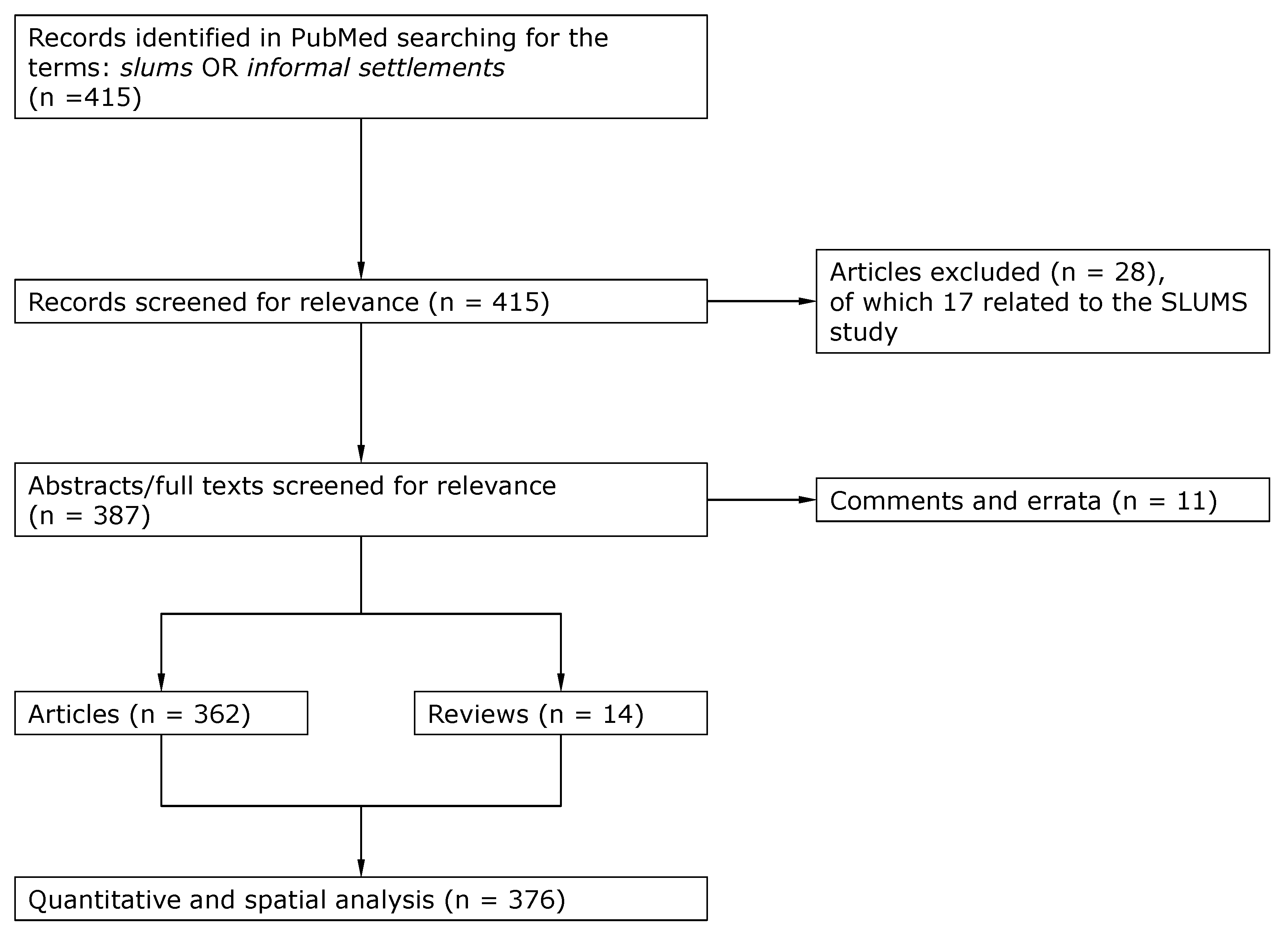

Looking at the geographical distribution of the slum classifications carried out in recent years, it is striking that this does not reflect the distribution of the slum population estimated worldwide [

29]. The distribution of studies on slum identification is shown in

Figure 1, which we formulated from the information in the study by Mahabir et al. [

29].

Especially in the case of sub-Saharan Africa, where the largest population increase is expected in the coming years, with a huge amount of this happing in slums [

46], further studies are necessary to assess the living situation of the inhabitants. This is particularly difficult because in many cities, it is very difficult to distinguish between formal and informal settlements [

28].

2.2. Information on Health

The literature on the relationship between

slums and

health has produced some reviews in recent years. The connection between slums and health was generally pointed out [

2,

3,

47], as well as the connection between slum upgrading and health [

5]. It was also shown that the physical environment and infrastructure intervention, such as road paving or water supply, have significant effects on the health of slum dwellers [

48]. Abdi et al. [

49] describe what kind of diseases should be investigated in slums (diabetes, hypertension, dengue fever, and anaemia). They refer to slums in Bangalore, India. Our aim is to generalize this approach to a global scale.

As stated above, Lilford et al. [

8] postulated in a recent study that space should be considered in health studies. On the basis of this work, we ask what global regions and on which scales studies on health in slums are conducted. Unfortunately, there is no database with information on slum health on a global scale. Therefore, we searched PubMed for journal articles with the keywords

slums or

informal settlements. Although, as mentioned above, other terms may also be used, these two terms are those most commonly used in literature and by the UN. We limited the keyword search to title and abstract, and we restricted the search to English articles from the last five years. Even though other platforms like Scopus or WebofScience also have an enormous amount of data, we chose PubMed because it has the largest amount of medical literature [

50], it is preferred for the research of biomedical studies [

51], and it is free to use [

50].

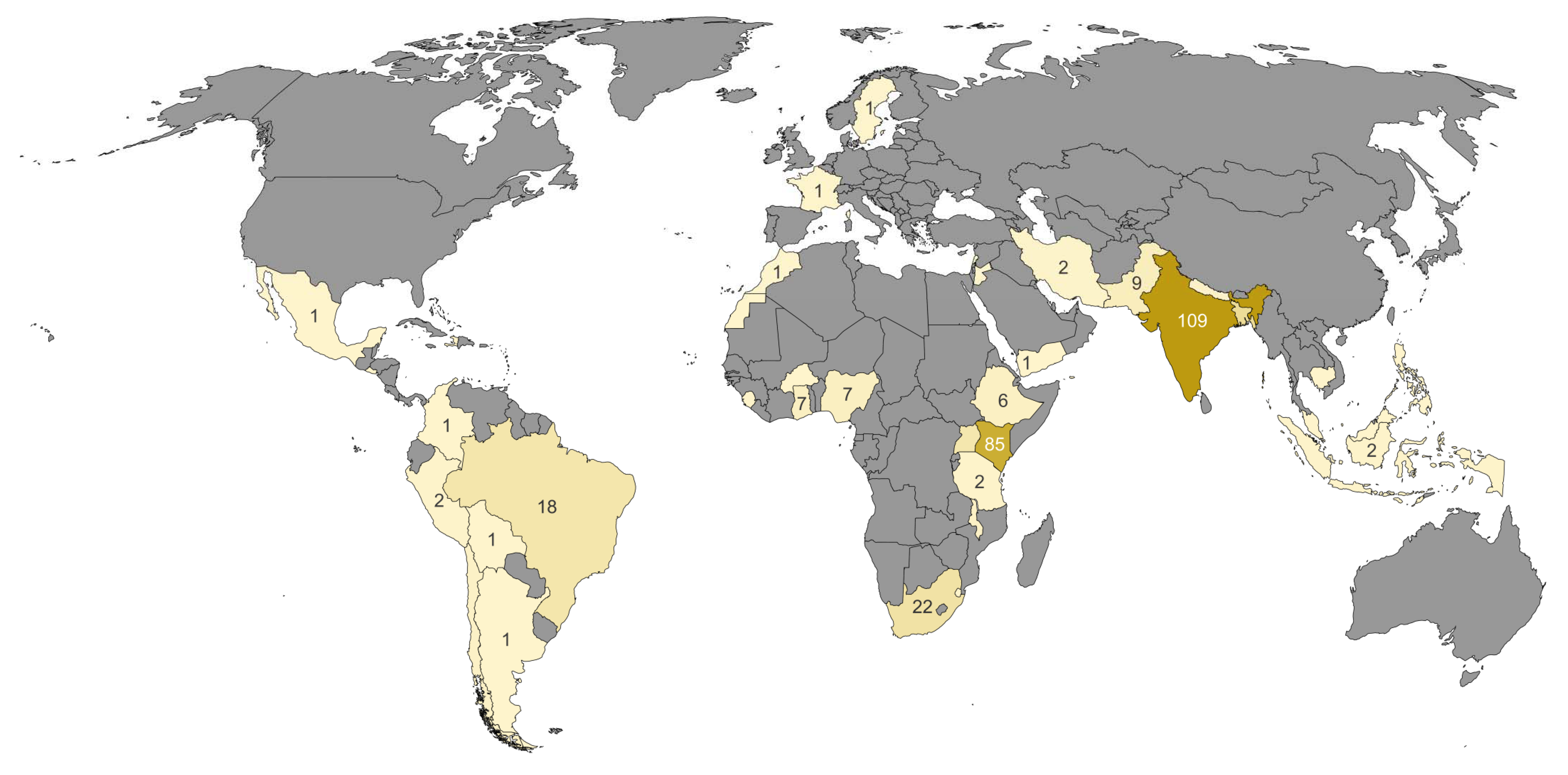

Searching for the terms slums or informal settlements, we found 415 articles. Of these, 11 were not related to the health of the slum dwellers, 17 others referred to results of SLUMS (Saint Louis University Mental Status), a test used to quantify dementia. Of the remaining 387 publications, 10 were comments and one was an erratum, which did not contain specific information or the text was not accessible.

The remaining publications included 14 reviews, mostly discussing problems on a global scale, and 362 articles. The flowchart according the adapted PRISMA guideline [

52] is shown in

Figure 2. We classified these 376 publications both spatially and medically using the categories shown in

Table 1.

The division into spatial scales was done using the following procedure: If one or two slums were mentioned in the study, we referred to them as slum specific studies. If more than two slums were examined in a study or if no specific number of slums were mentioned, we assigned the study to the city scale. If more than one city was examined and this or a specific region was explicitly mentioned, we designated the study as sub-national. If there was no specific information on city or region, the study was assigned to the country class. If more than one country was examined in the study and the countries were explicitly named, we called the study cross-national. Studies that described a topic on a global scale, e.g., reviews, were marked as global.

We divided the examined diseases into seven categories: communicable, non-communicable, underweight/malnutrition, sexual and maternal health/behavior, injuries, mental health, and non-specific.

The category

communicable contains diseases that have the potential to infect other persons mainly through bacteria or viruses, for example diarrhea, tuberculosis, and HIV. All diseases that cannot infect another person directly, like diabetes, cardiovascular/neurological problems, and cancer, are part of the category

non-communicable.

Underweight and malnutrition was classified as a category that includes food insecurity, wasting, and stunting, especially in children. The category

sexual and maternal health and behavior consists of all cases that concern sexual intercourse, contraception, pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding. All injuries caused by external violence, like blows, from weapons, and accidents were included in the category

injuries (physical trauma). The category

mental health covers diseases that have an influence on physiological well-being, for example depression, suicidal thoughts, and mourning. We classified as

non-specific all cases that could not be explicitly placed in one of the other six categories, like general studies on sanitation that do not investigate its influence on a specific infectious disease [

53] and fundamental reviews like Abdi et al. [

49].

We analyze the results according to different aspects in the following three sections. In the main text, we address examples of the found literature. The full classification can be found in the

Supplementary Materials (Table S1).

2.2.1. Analysis by Health Categories

In

Figure 3, the studies are classified according to the abovementioned categories. All publications analyzed here are listed in the

Supplementary Material in an .xlsx file, which lists the spatial scale, the medical category, the geographical entity, and the DOI. This allows the reader to trace all analyses we carried out and to look up the corresponding publications.

As expected, the most frequently investigated class of disease, with 111 studies, is

communicable diseases (29.5% of all studies). Of these, more than half of the studies (62) were conducted at city level. The communicable diseases most frequently studied in the context of slums were diarrheal diseases (e.g., [

54,

55]), HIV (e.g., [

56,

57]), and tuberculosis (e.g., [

58,

59]), as expected. The communicable diseases are followed by studies on

sexual and maternal behavior (13.6%). The main focus in these studies was on contraceptive methods [

60] or general studies on pregnancy health (e.g., [

61,

62]).

Nutritional issues were examined in 8.5% of the studies, mainly with regard to children (e.g., [

63,

64]).

Non-communicable diseases (8.2% of all studies) that are examined most frequently are cardiovascular diseases (e.g., [

65,

66]) or diabetes (e.g., [

67,

68]). There were only a few studies on cervical cancer (e.g., [

69]), confirming a statement in a recent report by the WHO [

70] that urges researchers not to neglect cancer in studies on the health of slum dwellers. In addition, there was no study on neurological diseases. With regard to

injury-related illnesses, which account for 5.9% of all studies, they were almost exclusively conducted on domestic (e.g., [

71,

72]) or partner-related violence (e.g., [

73]).

Mental health problems represent 5.6% of the total studies. Depression in particular has been studied regularly (e.g., [

74]), often in connection with abortion (e.g., [

75]).

Non-specific studies were mentioned 106 times, with most of the studies also being conducted on the city level (50%). These are, for example, studies on aging and the related effects or questions [

76,

77], studies on the influence of community centers [

78], noise exposure [

79], the impact of climate change on health [

80], the influence of smoke from cooking stations [

81], and general studies on sanitation that do not investigate its influence on a specific infectious disease.

Since our investigation focuses on the spatial scales of the studies, we refer to the large studies by Lilford et al. [

3] or Corburn and Sverdlik [

5], in which the different disease classes are discussed in detail.

It should be noted that even if infectious diseases are by far the greatest risk to the health of slum dwellers today, the study of other diseases should not be neglected. With regard to cancer, the World Health Organization (WHO) pointed out precisely these dangers in its latest report, since a focus on infectious diseases leads to a neglect of non-communicable diseases [

70].

It can be used to quickly identify PubMed publications of the last five years in regard to health and spatial categories.

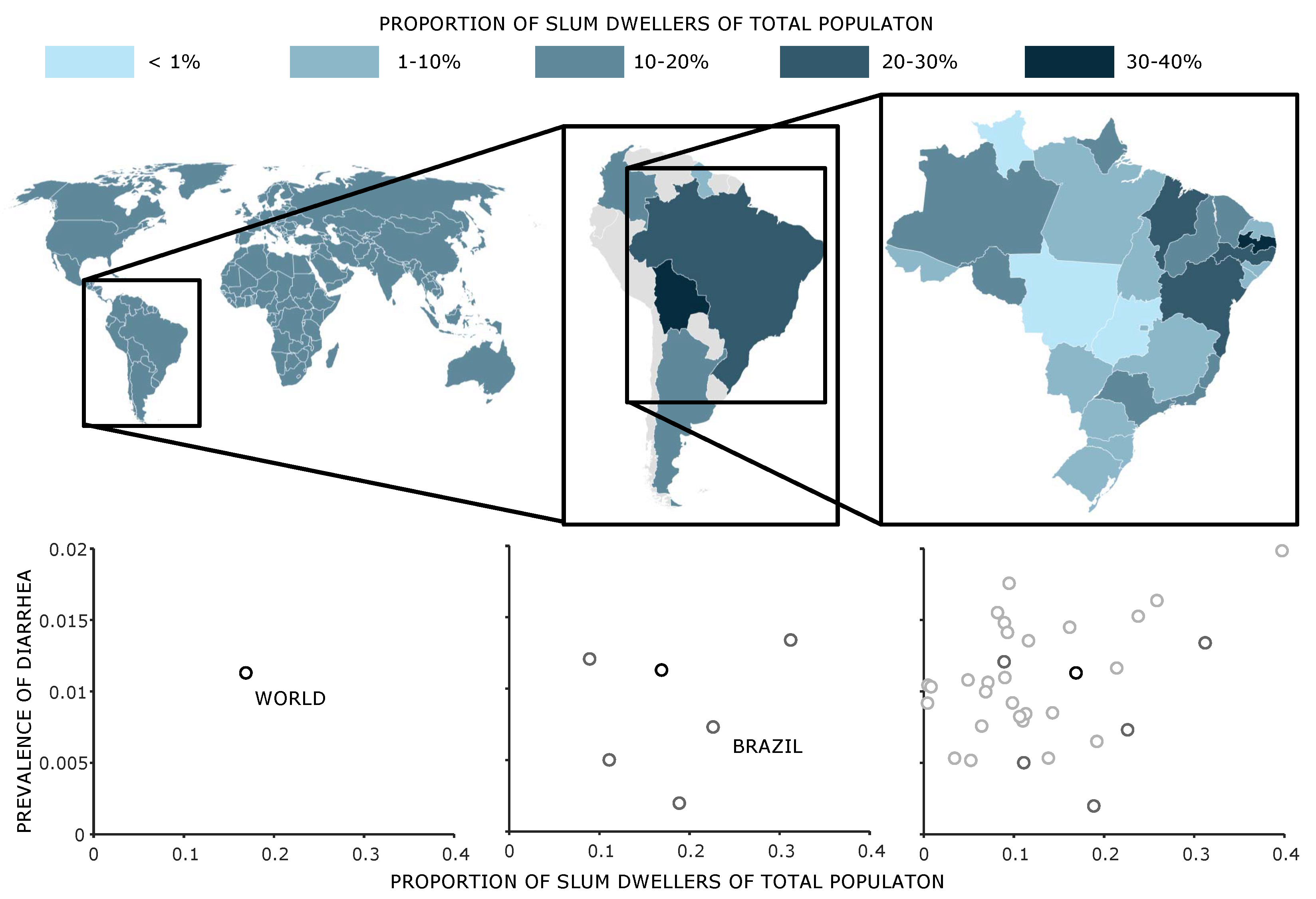

2.2.2. Analysis by Region

Figure 4 lists the studies on health and slums by country. Cross-national and global studies are not included in this figure, as they account for only a small proportion (5%) of all studies (see

Section 2.2.3).

We analyze the studies using the World Bank regions, shown in

Table 3. Except for Europe and the Middle East and North Africa, the number of slum dwellers per region is provided by the World Development Indicators (WDI) of the World Bank. Using this information and the 355 studies on the national or lower geographical scale, we calculated the number of studies per 10 million slum dwellers per region.

As expected, almost all studies were conducted in the Global South (Africa, South America, and Asia) [

28].

Europe. The only two exceptions are the studies on informal settlements of Roma from Sweden and France [

102,

103].

Sub-Saharan Africa. With 7.64 studies per 10 million inhabitants, sub-Saharan Africa has the second highest value. The studies that examine slum health in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) are mainly conducted in Kenya (85), Nigeria (7), Ghana (7), and Ethiopia (6). The 13 countries where the studies were conducted represent about 61% of the population of SSA. Although this is the largest proportion, the question arises whether the results found here can be applied to other countries in these regions. For example, there were no studies on slums in the Democratic Republic of Congo, although by population, it is the fourth largest African country.

If one takes a closer look at the studies for sub-Saharan Africa on the slum and city level, it is noticeable that by far the most studies were carried out in Kenya (78), especially in Kenya’s capital city Nairobi, and mainly in two specific slums. This fact can be mainly attributed to the fact that in Nairobi, a health study in slums was carried out in which the health conditions in slums were examined [

104]. Although Nairobi is by far the largest city in Kenya with 4.4 million inhabitants and accounts for about 10% of the population, the question arises whether the results can be transferred to other parts of the country (cf.

Figure 5, left). Even more critical is the question of whether the results of the studies carried out here can be transferred to the whole of sub-Saharan Africa, as the climatic conditions in this huge region differ considerably from one another.

A second example for a sub-Saharan country is Nigeria, which has a population of about 206 million people according to current UN estimates (2020). Six out of the seven mentioned studies were conducted for either Lagos or Enugu. Even with conservative population estimates for these cities, more than 50% of the population is not represented.

Similar to the study of Mahabir et al. [

29], it can be seen that the largest share of studies refers to well-known cities with slums, e.g., Nairobi in Kenya. Kenya and especially Nairobi is strongly overrepresented in the studies. The proportion of people in Nairobi, Kenya is marginal compared to all sub-Saharan Africa. The question is whether the living conditions and the illness conditions of the slums in Lagos can be compared with the environmental conditions of the slums in Nairobi.

South Asia. In comparison to its population, South Asia has the highest number of studies per slum inhabitant (

Table 3). Most of the studies were conducted in India (109) and Bangladesh (30). In contrast to the high number of studies for the slums of Nairobi, the medical studies for India are spread across the whole country (cf.

Figure 5, right), although the districts in the west are more strongly represented than those in the east. The two most populated cities Mumbai (21 studies) and Delhi (17 studies) have the largest number of studies in India. In five of the 12 districts where studies were conducted, more than one city was studied. In the neighboring Bangladesh, 30 studies were conducted, 22 of them in the capital, Dhaka. There is a similar concentration of studies in the capital as in Kenya. Further studies were conducted for Nepal (3) and Pakistan (9).

Compared with the African continent, which has a similar population size to India and Bangladesh, the studies are thus more evenly distributed and more in proportion to the population size.

Latin America and Caribbean. Looking at the number of studies per 10 million slum inhabitant of 3.2, it is about half as large for the Latin America and Caribbean region as for South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. There are studies for nine different countries Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Columbia, El Salvador, Haiti, Mexico, and Peru, and most of the studies are conducted in Brazil (18 studies). Both the studies within Brazil and in the entire Latin American region are relatively evenly distributed, as can be seen in

Figure 4.

East Asia and Pacific. The case of East Asia is very interesting. The World Bank estimates that there are about 325 million slum dwellers in this region. Although the number of slum dwellers in China is estimated to be about 180 million, our search conditions did not identify any studies for this country. Studies were conducted in only six countries Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, Melanesia, Pacific Islands, and Philippines. The number of studies per 10 million slum dwellers has the lowest value for this region (0.22).

Middle East and North Africa. Seven studies in five countries (Iran, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, and Yemen) have been carried out for this region, one in North Africa and the other six in the Middle East. Several of those studies relate to temporary informal settlements resulting from the armed conflicts in this region [

98,

105].

2.2.3. Analysis by Scale

Another way to analyze the literature is to look at the scales the slum health studies cover (

Figure 6). About 21.9% of the studies examined diseases at the

slum level. Of the 82 studies conducted at the slum level, 41 were located in Nairobi (50%), which means that most of the information on diseases on the slum level published in the last five years is limited to one city in eastern Africa. A breakdown by city can be seen in

Figure A1 in

Appendix A.

The geographical scale of cities has been studied the most. About half of all studies (55.2%) were conducted on the

city level. Of these, about one third (36%) were conducted in sub-Saharan Africa (28 in Nairobi, 12 in Kampala, 6 in Kisumu). All these cities are located in East Africa. Compared to their size, megacities such as Lagos, Nigeria (two studies) or Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo (no study) are severely underrepresented. About 25% (40 studies) were conducted in South Asia (19 Dhaka, 17 Mumbai, 16 Delhi). Here again, the three cities are in India or Bangladesh. The studies with their respective disease classes are listed in

Figure A2.

Out of the 23 sub-national studies, 14 were conducted in South Asia (10 India, 2 in Nepal, 1 in Bangladesh and in Pakistan), 5 in sub-Saharan Africa (4 in South Africa and 1 in Ethiopia), and 4 in Chile.

The 44 studies on national scales have been conducted mainly in India (13), Kenya (7), and South Africa (7).

Looking at the

cross-national scale, only eight studies are available. There is one cross-national study on communicable diseases [

84] in Burkina Faso and Kenya, one on malnutrition between Chile and Kenya [

106], one on nurturing care in Angola and Kenya [

107], one on contraceptive methods in Bangladesh and Kenya [

108], one on early child loss in South Africa and India [

109], and three non-specific on noise annoyance and sensitivity [

110] between dwellers of informal settlements in South Africa and inhabitants of Switzerland, one on community health in three Melanesian countries [

111], and one on urban growth and water access in sub-Saharan Africa [

112].

On a

global level, there are different reviews focusing on different aspects: van de Vijver et al. [

113] review health programs in slums, Corburn and Sverdlik [

5] slum upgrading, Ezeh et al. [

2] look at the history of these settlement forms, as well as social and geographical factors. Oliver et al. [

114] focus on water quality, Nelson et al. [

115] vaccinations for children, and Goudet et al. [

116] examine articles concerning malnutrition of children in slums.

In the context of this analysis, it must also be mentioned that the titles of the studies were often misleading, for example, by referring to countries when in the end only two slums in a city were examined (e.g., [

117]).

2.3. Conclusion of Reviews

We have seen that a lot of data are available, but only in very specific regions. The geographical scales most frequently studied are the city and slum level. What we also see clearly is that programs in which health data are recorded are very important. The program in Nairobi had a huge impact on our results [

104]. If a lot of information is available in a particular region or city, it is useful to analyze it, which leads to a high number of studies, but new studies are also developed to investigate the interaction with the results found there.

Often analyses in geography [

118] and medicine [

2] focus on the largest urban entities on different scales. Thus, studies are mainly conducted in well-known cities, such as Dhaka, Mumbai, or Nairobi, and in well-known slums, such as Kibera in Nairobi or Dharavi in Mumbai. However, this does not take into account the majority of the population, since urbanization processes mainly take place in medium-sized cities [

118] or medium-sized slums [

37].

The health status of slums is developing. If the focus of monitoring and observation is only on specific cities and their intervention programs for health improvement (see Nairobi), processes that occur in the immediate neighborhood could be overlooked.

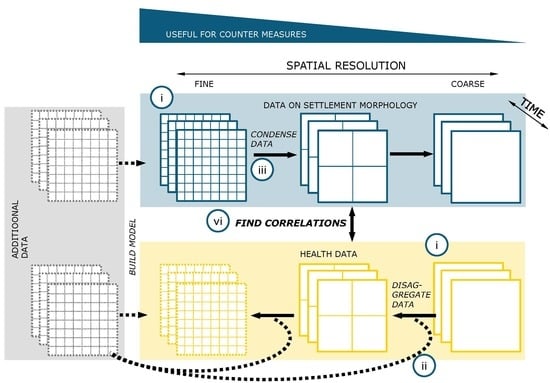

Sub-national and cross-national studies are only available in very small numbers, and intervention measures should take place on all regional scales. Therefore, information should also be available on all scales in order to be able to implement specific measures. What is often missing are studies that show sub-national differences (see application study) as well as studies that carry out cross-national investigations.

It should be investigated whether specific morphological characteristics correlate with specific settlement morphologies. On the basis of the results discussed so far, this is possible in detail, especially for Nairobi and specific regions of India, e.g., Mumbai or Delhi, since both settlement data and a larger number of studies on slum health are available for these cities.