Changes in Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in Response to COVID-19 and Their Associations with Mental Health in 3052 US Adults

Abstract

:1. Introduction

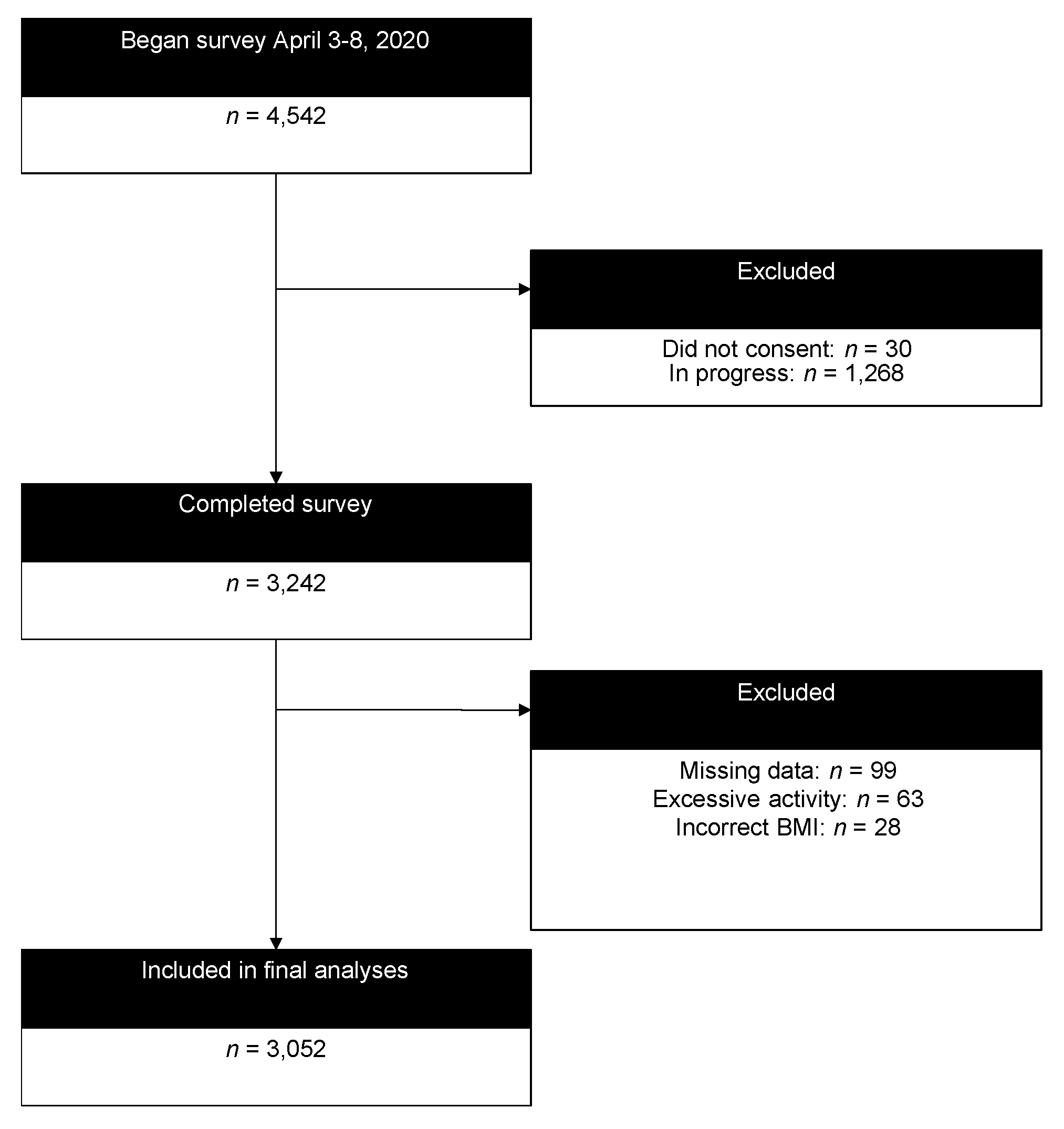

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Demographics and Health History

2.2. COVID-19-Related Public Health Restrictions

- Self-Isolation: For people who actually have the virus or suspect they may be infected. People who have been infected with the virus may be asked to self-isolate at home if they have no symptoms or are only mildly ill.

- Quarantine: For those who may have been exposed to the virus. They are asked to stay at home. Some people may choose to be asked to self-quarantine, meaning they do it voluntarily because they think they may have been exposed or they are being cautious.

- Shelter-in-place: People that are being asked to stay at home as much as possible, meaning they shouldn’t be out unless getting food, gas, or other essentials, or for medical reasons.

- Stay-at-home order: Residents can still go out for essential needs as long as they are practicing social distancing and “common sense”.

- Social distancing: means remaining out of congregate settings, avoiding mass gatherings, and maintaining distance (approximately 6 feet or 2 m) from others when possible.

2.3. COVID-19-Related Health Behaviors and Change

2.4. Mental Health

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Change in Physical Activity, Sitting Time, and Screen Time

3.3. Associations between Changes in Behavior, COVID-19 Public Health Restrictions, and Mental Health

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gostin, L.O.; Wiley, L.F. Governmental Public Health Powers During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Stay-at-home Orders, Business Closures, and Travel Restrictions. JAMA 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, Y.; Zhao, N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 112954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Hu, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, J.; Du, H.; Chen, T.; Li, R.; et al. Factors Associated With Mental Health Outcomes Among Health Care Workers Exposed to Coronavirus Disease 2019. JAMA Netw. Open 2020, 3, e203976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, S.X.; Wang, Y.; Rauch, A.; Wei, F. Unprecedented disruption of lives and work: Health, distress and life satisfaction of working adults in China one month into the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 112958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitbit Inc. The Impact of Coronavirus On Global Activity [Internet]. Fitbit Blog. 2020. Available online: https://blog.fitbit.com/covid-19-global-activity/ (accessed on 13 June 2020).

- Tison, G.H.; Avram, R.; Kuhar, P.; Abreau, S.; Marcus, G.M.; Pletcher, M.J.; Olgin, J.E. Worldwide Effect of COVID-19 on Physical Activity: A Descriptive Study. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd ed.; US Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Raglin, J.S. Exercise and mental health. Beneficial and detrimental effects. Sports Med. 1990, 9, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, B.R.; McDowell, C.P.; Hallgren, M.; Meyer, J.D.; Lyons, M.; Herring, M.P. Association of Efficacy of Resistance Exercise Training with Depressive Symptoms: Meta-analysis and Meta-regression Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashdown-Franks, G.; Firth, J.; Carney, R.; Carvalho, A.F.; Hallgren, M.; Koyanagi, A.; Rosenbaum, S.; Schuch, F.B.; Smith, L.; Solmi, M.; et al. Exercise as Medicine for Mental and Substance Use Disorders: A Meta-review of the Benefits for Neuropsychiatric and Cognitive Outcomes. Sports Med. 2020, 50, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP19-5068, NSDUH Series H-54); Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Rockville, MD, USA, 2019. Available online: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/ (accessed on 8 August 2020).

- Holmes, E.A.; O’Connor, R.C.; Perry, V.H.; Tracey, I.; Wessely, S.; Arseneault, L.; Ballard, C.; Christensen, H.; Silver, R.C.; Everall, I.; et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, E.H. Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale. Asian Nurs. Res. 2012, 6, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hughes, M.E.; Waite, L.J.; Hawkley, L.C.; Cacioppo, J.T. A Short Scale for Measuring Loneliness in Large Surveys: Results from Two Population-Based Studies. Res. Aging 2004, 26, 655–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haver, A.; Akerjordet, K.; Caputi, P.; Furunes, T.; Magee, C. Measuring mental well-being: A validation of the Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale in Norwegian and Swedish. Scand. J. Public Health 2015, 43, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubben, J.; Blozik, E.; Gillmann, G.; Iliffe, S.; von Renteln Kruse, W.; Beck, J.C.; Stuck, A.E. Performance of an abbreviated version of the Lubben Social Network Scale among three European community-dwelling older adult populations. Gerontologist 2006, 46, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dozois, D.J.A.; Dobson, K.S.; Ahnberg, J.L. A psychometric evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory–II. Psychological Assessment. 1998, 10, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G.K. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II; Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A.T.; Epstein, N.; Brown, G.; Steer, R.A. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1988, 56, 893–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekelund, U.; Steene-Johannessen, J.; Brown, W.J.; Fagerland, M.W.; Owen, N.; Powell, K.E.; Bauman, A.; Lee, I.M.; Series, L.P. Does physical activity attenuate, or even eliminate, the detrimental association of sitting time with mortality? A harmonised meta-analysis of data from more than 1 million men and women. Lancet 2016, 388, 1302–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hedges, L.V. Distribution Theory for Glass’s Estimator of Effect Size and Related Estimators. J. Educ. Stat. 1981, 6, 107–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, G.R.; Sloan, J.A.; Wyrwich, K.W. Interpretation of changes in health-related quality of life: The remarkable universality of half a standard deviation. Med. Care 2003, 41, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, N.M.; Laydon, D.; Nedjati-Gilani, G.; Imai, N.; Ainslie, K.; Baguelin, M.; Bhatia, S.; Boonyasiri, A.; Cucunuba Perez, Z.U.; Cuomo-Dannenburg, G.; et al. Impact of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs) to Reduce COVID- 19 Mortality and Healthcare Demand; Imperial College COVID-19 Response Team: London, UK, 2020; Available online: https://www.imperial.ac.uk/media/imperial-college/medicine/sph/ide/gida-fellowships/Imperial-College-COVID19-NPI-modelling-16-03-2020.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2020).

- Hamer, M.; Kivimäki, M.; Gale, C.R.; Batty, G.D. Lifestyle risk factors, inflammatory mechanisms, and COVID-19 hospitalization: A community-based cohort study of 387,109 adults in UK. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 184–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, A.A.; Koehmstedt, C.; Kop, W.J. Mental health consequences of exercise withdrawal: A systematic review. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2017, 49, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, C.P.; Dishman, R.K.; Gordon, B.R.; Herring, M.P. Physical Activity and Anxiety: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019, 57, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.C.; Nguyen, M.H.; Do, B.N.; Tran, C.Q.; Nguyen, T.T.; Pham, K.M.; Pham, L.V.; Tran, K.V.; Duong, T.T.; Tran, T.V.; et al. People with Suspected COVID-19 Symptoms Were More Likely Depressed and Had Lower Health-Related Quality of Life: The Potential Benefit of Health Literacy. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edwards, M.K.; Loprinzi, P.D. Effects of a Sedentary Behavior-Inducing Randomized Controlled Intervention on Depression and Mood Profile in Active Young Adults. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2016, 91, 984–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamminen, N.; Reinikainen, J.; Appelqvist-Schmidlechner, K.; Borodulin, K.; Mäki-Opas, T.; Solin, P. Associations of physical activity with positive mental health: A population-based study. Ment. Health Phys. 2020, 18, 100319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallgren, M.; Nguyen, T.T.; Owen, N.; Stubbs, B.; Vancampfort, D.; Lundin, A.; Dunstan, D.; Bellocco, R.; Lagerros, Y.T. Cross-sectional and prospective relationships of passive and mentally active sedentary behaviours and physical activity with depression. Br. J. Psychiatry 2019, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Characteristic | N (%) or Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 18–24 | 508 (16.64) |

| 25–34 | 470 (15.40) |

| 34–44 | 419 (13.73) |

| 45–54 | 376 (12.32) |

| 55–64 | 474 (15.53) |

| 65–74 | 522 (17.10) |

| 75+ | 283 (9.27) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 1151 (37.63) |

| Female | 1897 (62.01) |

| Transgender | 4 (0.13) |

| Race (white) | 2848 (93.10) |

| BMI | 26.84 ± 5.64 |

| Underweight (BMI < 18.5) | 53 (1.74) |

| Normal (BMI 18.5–25) | 1281 (41.97) |

| Overweight (BMI 25–30) | 990 (32.44) |

| Obese (BMI > 30) | 728 (23.85) |

| Smoker | 80 (2.62) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married/in a relationship | 2070 (67.67) |

| Widowed | 93 (3.04) |

| Separated/divorced | 178 (5.82) |

| Never married | 711 (23.24) |

| Education | |

| Up to high school graduate | 56 (1.83) |

| Up to college graduate | 1656 (54.14) |

| Graduate degree | 1340 (43.81) |

| Employment | |

| Employed | 1747 (57.11) |

| Retired | 785 (25.66) |

| Unemployed | 403 (13.17) |

| Other | 97 (3.17) |

| Chronic Conditions | |

| 0 | 2163 (70.71) |

| 1 | 263 (8.60) |

| 2+ | 626 (20.46) |

| Depression | |

| Minimal | 2368 (77.59) |

| Mild | 375 (12.29) |

| Moderate | 217 (7.11) |

| Severe | 92 (3.01) |

| Anxiety | |

| Low | 2836 (92.92) |

| Moderate | 183 (6.00) |

| High | 33 (1.08) |

| Depression | Anxiety | Loneliness | Stress | Social Network | Positive Mental Health | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted R2 | p-Value | Adjusted R2 | p-Value | Adjusted R2 | p-Value | Adjusted R2 | p-Value | Adjusted R2 | p-Value | Adjusted R2 | p-Value | ||

| Goodness of Fit | 0.268 | <0.0001 | 0.219 | <0.0001 | 0.168 | <0.0001 | 0.202 | <0.0001 | 0.046 | <0.0001 | 0.255 | <0.0001 | |

| n | b (SE) | p-Value | b (SE) | p-Value | b (SE) | p-Value | b (SE) | p-Value | b (SE) | p-Value | b (SE) | p-Value | |

| Physical Activity | |||||||||||||

| Maintained high | 798 | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | ||||||

| Increased | 152 | −0.505 (0.645) | 0.434 | 0.066 (0.677) | 0.923 | 0.001 (0.136) | 0.996 | −0.133 (0.244) | 0.585 | 0.305 (0.222) | 0.169 | 0.189 (0.345) | 0.585 |

| Decreased | 563 | 1.960 (0.417) | <0.001 | 0.596 (0.411) | 0.148 | 0.340 (0.096) | <0.001 | 0.522 (0.155) | <0.001 | −0.269 (0.149) | 0.072 | −1.010 (0.230) | <0.001 |

| Maintained low | 1539 | 0.629 (0.318) | 0.048 | 0.248 (0.320) | 0.439 | 0.078 (0.075) | 0.302 | 0.377 (0.124) | 0.002 | −0.389 (0.119) | 0.001 | −0.629 (0.182) | <0.001 |

| Sitting Time | |||||||||||||

| Maintained low | 1041 | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | ||||||

| Decreased | 85 | 0.587 (0.972) | 0.546 | 1.497 (0.944) | 0.113 | −0.067 (0.197) | 0.728 | −0.015 (0.329) | 0.964 | 0.074 (0.273) | 0.786 | −0.122 (0.505) | 0.809 |

| Increased | 582 | 0.918 (0.441) | 0.037 | 0.946 (0.445) | 0.034 | 0.195 (0.097) | 0.045 | 0.253 (0.154) | 0.102 | −0.163 (0.149) | 0.275 | −0.673 (0.234) | 0.005 |

| Maintained high | 1344 | −0.199 (0.348) | 0.566 | −0.064 (0.344) | 0.852 | 0.046 (0.078) | 0.554 | −0.068 (0.131) | 0.604 | −0.040 (0.126) | 0.750 | −0.036 (0.192) | 0.853 |

| Screen Time | |||||||||||||

| Maintained low | 1512 | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | REF | ||||||

| Decreased | 45 | −0.623 (1.095) | 0.569 | 0.345 (1.203) | 0.774 | −0.495 (0.198) | 0.013 | −0.261 (0.468) | 0.577 | 0.762 (0.393) | 0.052 | 0.412 (0.641) | 0.520 |

| Increased | 562 | 1.924 (0.441) | <0.001 | 1.341 (0.454) | 0.003 | 0.340 (0.095) | <0.001 | 0.590 (0.154) | <0.001 | −0.069 (0.145) | 0.632 | −0.920 (0.239) | <0.001 |

| Maintained high | 933 | 0.375 (0.392) | 0.339 | 0.474 (0.375) | 0.206 | 0.146 (0.085) | 0.087 | 0.126 (0.137) | 0.361 | −0.156 (0.133) | 0.243 | −0.451 (0.202) | 0.026 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Meyer, J.; McDowell, C.; Lansing, J.; Brower, C.; Smith, L.; Tully, M.; Herring, M. Changes in Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in Response to COVID-19 and Their Associations with Mental Health in 3052 US Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6469. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186469

Meyer J, McDowell C, Lansing J, Brower C, Smith L, Tully M, Herring M. Changes in Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in Response to COVID-19 and Their Associations with Mental Health in 3052 US Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(18):6469. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186469

Chicago/Turabian StyleMeyer, Jacob, Cillian McDowell, Jeni Lansing, Cassandra Brower, Lee Smith, Mark Tully, and Matthew Herring. 2020. "Changes in Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in Response to COVID-19 and Their Associations with Mental Health in 3052 US Adults" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 18: 6469. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186469

APA StyleMeyer, J., McDowell, C., Lansing, J., Brower, C., Smith, L., Tully, M., & Herring, M. (2020). Changes in Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior in Response to COVID-19 and Their Associations with Mental Health in 3052 US Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(18), 6469. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186469