Culturally Sensitive Health Education in the Caribbean Diaspora: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

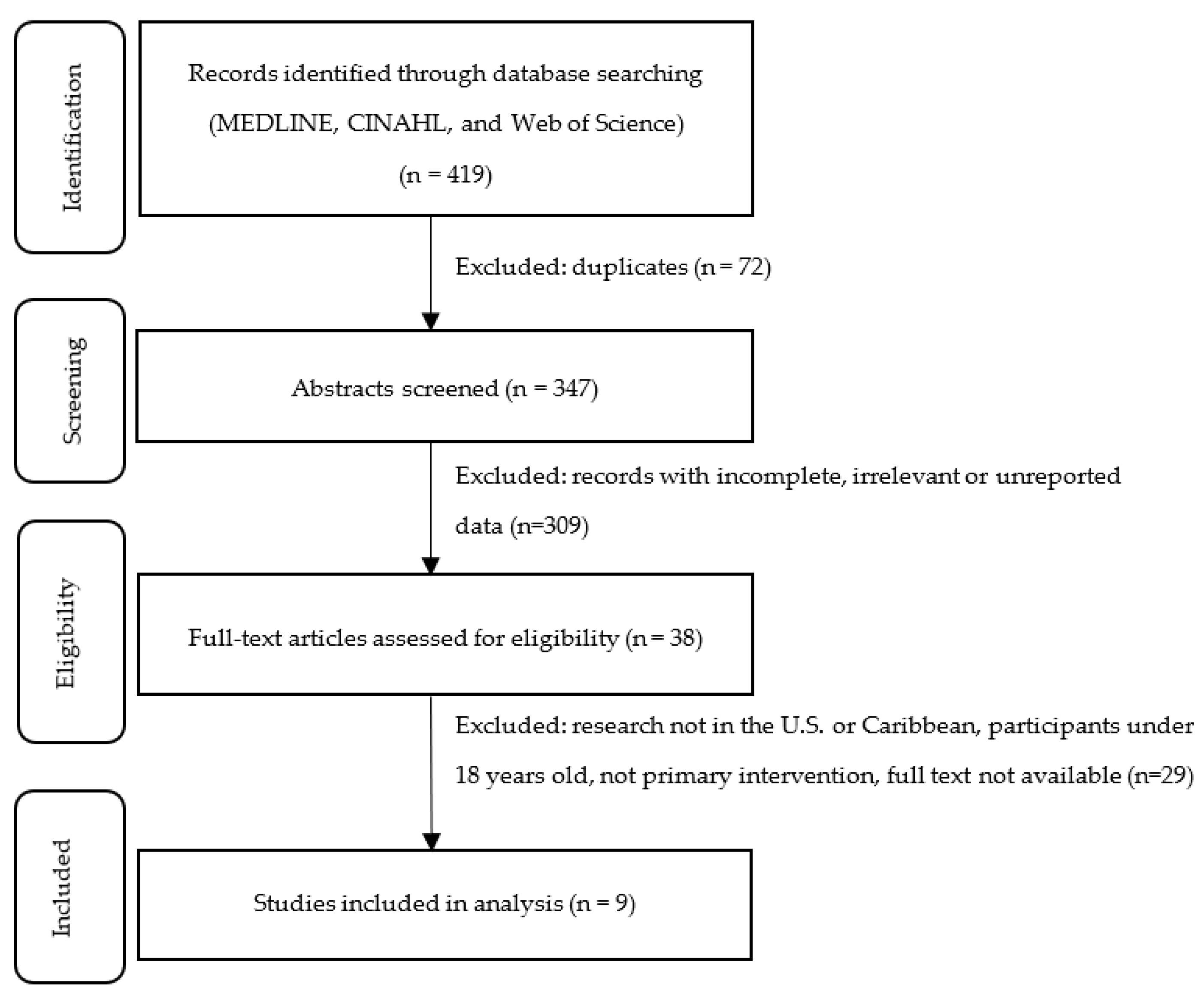

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description of Studies

3.2. Analysis of Features

3.2.1. Diet

3.2.2. Diabetes

3.2.3. Physical Activity

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Year | Author | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | Q14 | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | Less | No | NA | NR | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Fair |

| 2010 | Osborn | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | Good |

| 2011 | Partapsingh | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Good |

| 2011 | Chidum | Yes | NR | Yes | No | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | NR | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Fair |

| 2013 | Greenlee | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Good |

| Year | Author | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | Antoine-Jonville | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | NR | Yes | Yes | NR | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Fair |

| 2014 | West-Pollak | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | No | Yes | Yes | NA | Good |

| 2017 | Maliszewski | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | NR | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Fair |

| 2018 | Thomas | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | NR | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Fair |

References

- Hodge, D.R.; Jackson, K.F.; Vaughn, M.G. Culturally Sensitive Interventions and Health and Behavioral Health Youth Outcomes: A Meta-Analytic Review. Soc. Work Health Care 2010, 49, 401–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haffizulla, F.S.; Ramoutar, A.; Eason, A.; Hardigan, P. Caribbean Diaspora Healthy Nutrition Outreach Project (CDHNOP): A Qualitative and Quantitative Approach to Caribbean Health. Ann. Glob. Health 2020, 86, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zong, J.; Batalova, J. Caribbean Immigrants in the United States, 2019. Migration Information Source. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/caribbean-immigrants-united-states-2017 (accessed on 24 March 2020).

- U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey (ACS). Available online: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/ (accessed on 28 March 2020).

- Bennett, N.R.; Francis, D.K.; Ferguson, T.S.; Hennis, A.J.; Wilks, R.J.; Harris, E.N.; MacLeish, M.M.; Sullivan, L.W. Disparities in diabetes mellitus among Caribbean populations: A scoping review. Int. J. Equity Health 2015, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Griffith, D.M.; Johnson, J.L.; Zhang, R.; Neighbors, H.W.; Jackson, J.S. Ethnicity, nativity, and the health of American Blacks. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2011, 22, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Commodore-Mensah, Y.; Matthie, N.; Wells, J.; Dunbar, S.B.; Himmelfarb, C.D.; Cooper, L.A.; Chandler, R.D. African Americans, African Immigrants, and Afro-Caribbeans Differ in Social Determinants of Hypertension and Diabetes: Evidence from the National Health Interview Survey. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2018, 5, 995–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, Y.; De La Cruz, G.P. The Foreign Born from Latin America and the Caribbean: 2010. Available online: https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2011/acs/acsbr10-15.html (accessed on 28 March 2020).

- Francis, D.K.; Bennett, N.R.; Ferguson, T.S.; Hennis, A.J.; Wilks, R.J.; Harris, E.N.; MacLeish, M.M.; Sullivan, L.W. Disparities in cardiovascular disease among Caribbean populations: A systematic literature review. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horlyck-Romanovsky, M.F.; Fuster, M.; Echeverria, S.E.; Wyka, K.; Leung, M.M.; Sumner, A.E.; Huang, T.T. Black Immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean Have Similar Rates of Diabetes but Africans Are Less Obese: The New York City Community Health Survey 2009–2013. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2019, 6, 635–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidulescu, A.; Francis, D.K.; Ferguson, T.S.; Bennett, N.R.; Hennis, A.J.; Wilks, R.; Harris, E.N.; MacLeish, M.; Sullivan, L.W. Disparities in hypertension among black Caribbean populations: A scoping review by the U.S. Caribbean Alliance for Health Disparities Research Group (USCAHDR). Int. J. Equity Health 2015, 14, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- White, M.; Adams, J.; Heywood, P. How and why do interventions that increase health overall widen inequalities within populations? In Social Inequality and Public Health; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 64–81. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, E.M.; Liu, J.J.; Bhopal, R.; White, M.; Johnson, M.R.; Netto, G.; Wabnitz, C.; Sheikh, A. Behavior change interventions to improve the health of racial and ethnic minority populations: A tool kit of adaptation approaches. Milbank Q. 2013, 91, 811–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mitchell, J.A.; Hawkins, J. Current approaches to support the psychosocial care of African American adults with diabetes: A brief review. Soc. Work Public Health 2014, 29, 518–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smalls, B.L.; Walker, R.J.; Bonilha, H.S.; Campbell, J.A.; Egede, L.E. Community Interventions to Improve Glycemic Control in African Americans with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systemic Review. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2015, 7, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Utz, S.W.; Williams, I.C.; Jones, R.; Hinton, I.; Alexander, G.; Yan, G.; Moore, C.; Blankenship, J.; Steeves, R.; Oliver, M.N. Culturally tailored intervention for rural African Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Educ. 2008, 34, 854–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Williams, I.C.; Utz, S.W.; Hinton, I.; Yan, G.; Jones, R.; Reid, K. Enhancing diabetes self-care among rural African Americans with diabetes: Results of a two-year culturally tailored intervention. Diabetes Educ. 2014, 40, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Peña-Purcell, N.C.; Jiang, L.; Ory, M.G.; Hollingsworth, R. Translating an evidence-based diabetes education approach into rural african-american communities: The “wisdom, power, control” program. Diabetes Spectr. 2015, 28, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bogner, H.R.; de Vries, H.F. Integrating type 2 diabetes mellitus and depression treatment among African Americans: A randomized controlled pilot trial. Diabetes Educ. 2010, 36, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb Hooper, M.; Baker, E.A.; Robinson, R.G. Efficacy of a DVD-based smoking cessation intervention for African Americans. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2014, 16, 1327–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cherrington, A.; Williams, J.H.; Foster, P.P.; Coley, H.L.; Kohler, C.; Allison, J.J.; Kiefe, C.I.; Volkman, J.E.; Houston, T.K. Narratives to enhance smoking cessation interventions among African-American smokers, the ACCE project. BMC Res. Notes 2015, 8, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- LeFevre, M.L. Behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2014, 161, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gany, F.M.; Herrera, A.P.; Avallone, M.; Changrani, J. Attitudes, knowledge, and health-seeking behaviors of five immigrant minority communities in the prevention and screening of cancer: A focus group approach. Ethn. Health 2006, 11, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarado, M.; Murphy, M.M.; Guell, C. Barriers and facilitators to physical activity amongst overweight and obese women in an Afro-Caribbean population: A qualitative study. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2015, 12, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Glasziou, P.P.; Boutron, I.; Milne, R.; Perera, R.; Moher, D.; Altman, D.G.; Barbour, V.; Macdonald, H.; Johnston, M.; et al. Better Reporting of Interventions: Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) Checklist and Guide. BMJ 2014, 348, g1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Osborn, C.Y.; Amico, K.R.; Cruz, N.; O’Connell, A.A.; Perez-Escamilla, R.; Kalichman, S.C.; Wolf, S.A.; Fisher, J.D. A brief culturally tailored intervention for Puerto Ricans with type 2 diabetes. Health Educ. Behav. 2010, 37, 849–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Less, L.A.; Ragoobirsingh, D.; Morrison, E.Y.; Boyne, M.; Johnson, P.A. A preliminary report on an assessment of a community-based intervention for diabetes control in adults with type 2 diabetes. Fam. Pract. 2010, 27 (Suppl. 1), i46–i52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Partapsingh, V.A.; Maharaj, R.G.; Rawlins, J.M. Applying the Stages of Change model to Type 2 diabetes care in Trinidad: A randomised trial. J. Negat. Results Biomed. 2011, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- West-Pollak, A.; Then, E.P.; Podesta, C.; Hedelt, A.; Perry, M.L.; Izarnotegui, W.V.; Perez, M.; Villegas, A.; Baez, N.I.; Bassa, R.; et al. Impact of a novel community-based lifestyle intervention program on type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular risk in a resource-poor setting in the Dominican Republic. Int. Health 2014, 6, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidum, E.; Agbai, D.; Fidelis, O.; Teppany, S.; Martina, R.; Rian, E.; Verdine, D.; Alida, S.; Hasina, M.; Altheia, J. Self-monitoring of blood glucose improved glycaemic control and 10-year coronary heart disease risk profile of type 2 diabetic patients. Chin. Med. J. Engl. 2011, 124, 166–171. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, N.M. Caribbean (English-Speaking) Women in the United States: Cooking for Diabetes Prevention and Management. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2018, 20, 1025–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maliszewski, G.; Enriquez, M.; Cheng, A.L.; Logan, P.; Watts, J. Development and feasibility of a community-partnered nutrition intervention targeting rural migrant communities in the Dominican Republic. Public Health Nurs. 2017, 34, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenlee, H.A.; Crew, K.D.; Mata, J.M.; McKinley, P.S.; Rundle, A.G.; Zhang, W.; Liao, Y.; Tsai, W.Y.; Hershman, D.L. A pilot randomized controlled trial of a commercial diet and exercise weight loss program in minority breast cancer survivors. Obesity 2013, 21, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Antoine-Jonville, S.; Lalanne-Mistrih, M.L.; Tressières, B.; Monjo, R.; Hue, O. Nou tout an dlo-la: A swimming-based physical activity promotion program. Public Health 2013, 127, 967–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Study Quality Assessment Tools. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed on 17 January 2021).

- Glazier, R.H.; Bajcar, J.; Kennie, N.R.; Willson, K. A systematic review of interventions to improve diabetes care in socially disadvantaged populations. Diabetes Care 2006, 29, 1675–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gucciardi, E.; Chan, V.W.; Manuel, L.; Sidani, S. A systematic literature review of diabetes self-management education features to improve diabetes education in women of Black African/Caribbean and Hispanic/Latin American ethnicity. Patient Educ. Couns. 2013, 92, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2020; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/pdfs/data/statistics/national-diabetes-statistics-report.pdf (accessed on 28 March 2020).

- Attridge, M.; Creamer, J.; Ramsden, M.; Cannings-John, R.; Hawthorne, K. Culturally appropriate health education for people in ethnic minority groups with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014, 9, Cd006424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Israel, B.A.; Coombe, C.M.; Cheezum, R.R.; Schulz, A.J.; McGranaghan, R.J.; Lichtenstein, R.; Reyes, A.G.; Clement, J.; Burris, A. Community-based participatory research: A capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. Am. J. Public Health 2010, 100, 2094–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masuda, J.R.; Creighton, G.; Nixon, S.; Frankish, J. Building capacity for community-based participatory research for health disparities in Canada: The case of “Partnerships in Community Health Research”. Health Promot. Pract. 2011, 12, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naqshbandi, M.; Harris, S.B.; Macaulay, A.C.; Comeau, J.; Piché, J.; Montour-Lazare, D. Lessons learned in using community-based participatory research to build a national diabetes collaborative in Canada. Prog. Community Health Partnersh. 2011, 5, 405–415. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| Search Terms | |

|---|---|

| Population | Caribbean or West Indies or Afro-Caribbean |

| Intervention | education or coaching or video or printed materials ortraining or radio |

| Outcomes | nutrition or diet or exercise or physical activity |

| Name | Theme | Objective | Study Design | Program | Program Provider | Delivery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culturally tailored intervention for Puerto Ricans with type 2 diabetes [27] | Diabetes Diet Physical activity | To determine the effect of an Information–Motivation–Behavioral Skills (IMB) intervention on diabetes self-care behaviors and glycemic control. | Randomized controlled trial (RCT) | The information–motivation–behavioral skills (IMB) model of health behavior change informed the design of a brief, culturally tailored diabetes self-care intervention for Puerto Ricans with type 2 diabetes. A flipchart, available in English and Spanish, presented information on food label reading, diet adherence, physical activity, and glycemic control (HbA1c). The session consisted of a brief introduction, information on diabetes prevalence in Puerto Ricans, motivational interviewing, and behavioral skills building. Patients were also provided with supplemental materials. | Bilingual medical assistant of Puerto Rican heritage | Group |

| Community-based intervention for type 2 diabetes control [28] | Diabetes Diet Physical activity | To evaluate the effectiveness of lay diabetes facilitators (LDFs) to increase knowledge and improve control among persons with diabetes. | Nonrandomized controlled trial | Two types of education sessions were conducted: one-to-one and group. The group sessions were conducted at the health centers on days when clients came for regular three-monthly visits and were limited to 10–12 patients. Those unable to attend had education sessions at home when the LDFs visited. The education gave focus to the timing of meals in relation to prescription of diabetes medication, physical activities, blood glucose monitoring, and hypoglycemia. | Community persons trained as lay diabetes facilitators | Individual and group |

| Applying the Stages of Change model to type 2 diabetes care [29] | Diabetes Diet Physical activity | To improve glycemic control among Type-2 diabetics using patient-physician consultations guided by the Stages of Change (SOC) model. | RCT | The intervention consisted of identifying each patient’s SOC for managing their diabetes by diet, exercise, and medications and applying personalized, stage-specific care during the patient–physician consultations based on the SOC model. | Physicians | Individual |

| Name | Theme | Objective | Study Design | Program | Program Provider | Delivery |

| Community-based lifestyle intervention program on type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular risk [30] | Diabetes Diet Physical activity | To assess the development of a cost-effective and sustainable approach to lifestyle modification in underdeveloped countries that can be implemented using community members as healthcare champions. | One group, pretest–posttest design | In a 1-day session, trained lifestyle educators from the USA trained ten lay community members to lead groups oriented to a lifestyle change. Community leaders met with assigned patient groups monthly for 1 year. | Lay community leaders | Group |

| Self-monitoring of blood glucose [31] | Diabetes | To assess the difference in glycemic control and coronary heart disease (CHD) risk levels of experimental type 2 diabetes patients provided with facilities for self-monitoring blood glucose and their counterparts without such facilities. | RCT | Intervention group was given glucose meters and testing strips that could last 3 months (90 days). Furthermore, members of the intervention group (glucose meters users) were trained on how to use the glucose meters and data documentation | Clinic staff | Group |

| Cooking for Diabetes Prevention and Management [32] | Diabetes Diet | To assess health behaviors of Caribbean–American women and to assess the usefulness of a website in increasing awareness of diabetes and diabetes prevention. | One group, pretest–posttest design | Online survey with seven 2-min videos of cooking instructions for modified traditional Caribbean meals | Research Fellows produced videos of the traditional Caribbean meals | Individual |

| Community-partnered nutrition intervention in rural communities [33] | Diet | To assess the feasibility and acceptability of culturally appropriate nutritional intervention programs in rural Dominican Republic | One group, pretest–posttest design | The intervention used a psychoeducational approach to develop a collaborative partnership between two not-for-profit organizations. The program consisted of (1) individualized nutritional counseling; (2) a brief culturally appropriate diet video in Spanish or Creole; (3) an interactive food card activity to enhance the skills learned in the video. | Members of the Light a Candle Foundation | Individual |

| Curves Weight Management Program [34] | Diet Physical activity | To examine the effects and feasibility of the commercial Curves weight loss program among Hispanic, African American, and Afro-Caribbean breast cancer survivors | RCT | Participants were given access to Curves fitness centers and a Curves diet plan, which was taught by Curves staff via a standardized nutrition course that made use of a book, DVDs, and an instructor’s manual, all published by Curves. | Curves Weight Management Program staff and bilingual nutrition instructors | Group and Individual |

| Swimming-based physical activity promotion program [35] | Physical activity | To promote short- and long-term participation in physical activities through the developmentof personal skills, self-confidence, and social networking | One group, pretest–posttest design | Each participant followed the same schedule during the intervention period: two swimming sessions (1 h each) in the first week and one swimming session plus another 2.5-h session of sailing or kayaking in the following week, with this alternating pattern repeated for a total of five times. | Qualified sports educator | Group |

| Name | Setting | Duration/Frequency | Tailoring | Adherence | Quality Assessment | Primary Outcomes |

| Culturally tailored intervention for Puerto Ricans with type 2 diabetes [27] | Primary care clinic at an urban hospital in the Northeast US | Single 90 min (60 min allocated to diet content and 30 min to exercise content) | Language Culture Needs Assessment | Diet and Physical Activity adherence was measured with the Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities questionnaire (SDSCA). | Good | Laboratory blood testing showed mean HbA1c score decreased in both groups, but only the intervention group showed significant improvement from baseline (M = 7.76, SD = 1.37) to follow-up (M = 7.28, SD = 1.29), (p < 0.008). The control group’s HbA1c decrease from baseline (M = 7.45, SD = 1.58) to follow-up (M = 7.18, SD = 1.54) and was not significant, with a Bonferroni adjustment of 0.01 (p < 0.047). |

| Name | Setting | Duration/Frequency | Tailoring | Adherence | Quality Assessment | Primary Outcomes |

| Community-based intervention for type 2 diabetes control [28] | 16 LDF health centers in Jamaica | Three monthly visits for a six-month period | Language Culture | LDFs used three patient self-monitoring forms (personal eating tracker, physical activity log, self-blood glucose readings) to track individual progress. | Fair | Laboratory blood testing showed that mean HbA1c for the intervention and comparison groups were similar at baseline (7.9% versus 8.0%; p-value >0.58). However, at 6 months, the intervention group had a reduction in HbA1c of 0.6%, while the comparison group had an increase of 0.6% (p < 0.001). |

| Applying the Stages of Change model to type 2 diabetes care [29] | Ste. Madeleine Health Centre (SMHC) in south Trinidad | Two days per month for 48 weeks | Needs Assessment | 58 of the 61 patients completed the intervention | Good | Laboratory blood testing showed the mean increase in HbA1c for the intervention group was 0.52% (SE 0.17) compared to that at baseline. The change in glycemic control for the control group was a mean increase in HbA1c of 1.09% (SE 0.18) compared to that at baseline. |

| Community-based lifestyle intervention program on type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular risk [30] | Club organization in Villa Juana, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic | Once a month for one year | Language Needs Assessment | Of the 79 patients enrolled in group therapy during the first 6 months, 10 attended all five meetings, 36 attended four, 19 attended three, and 14 attended two; 59 patients returned for follow-up HbA1c measurement. | Good | Patients showed significant improvements after 6 months in systolic blood pressure (p = 0.001), diastolic blood pressure (p = 0.000002), and HbA1c (p = 0.015). HbA1c improved further at 1 year (p = 0.005). |

| Self-monitoring of blood glucose [31] | Lifestyle Disease Clinics (primary care clinic) in Tobago | One training session with a six-month follow-up period | Language | Weekly follow-up phone call for six months | Fair | Laboratory blood testing showed that mean HbA1c of the intervention group improved significantly at three months (9.6 ± 0.3% vs. 7.8 ± 0.3%, p <0.001) and six months (9.6 ± 0.4% vs. 7.5 ± 0.3%, p < 0.001); CHD risk level of the intervention group was reduced by nearly one-half after three months (7.4 ± 1.3% vs. 4.3 ± 0.7%, p = 0.056). |

| Name | Setting | Duration/Frequency | Tailoring | Adherence | Quality Assessment | Primary Outcomes |

| Cooking for Diabetes Prevention and Management [32] | Online | One-time online survey | Language Culture | Not reported | Fair | Self-reported survey results showed that self-efficacy for cooking healthy before exploring the website was a mean of 3.52 between 40% and 60% confident (SD = 1.509) versus the after mean of 4.59 (closest to 80% confident or a “good” level of confidence, SD = 1.154; t = −10.353, df = 147; p < 0.001). |

| Community-partnered nutrition intervention targeting rural migrant communities [33] | Mobile medical clinics in 6 rural Dominican Republic | The one-session intervention was provided at three time-points. Participants were allowed to repeat the intervention, if desired. | Language Culture Needs Assessment | Not reported | Fair | Self-reported survey results showed that the difference between pre- and posttest scores was found to be significant for participants who had received the intervention for the first time: t(306) = 34.3, p < 0.001, for knowledge score; t(306) = 19.77, p < 0.001, for energy category; t(306) = 23.84, p < 0.001, for protection from illness category; t(306) = 28.70, p < 0.001, for growth category. |

| Curves Weight Management Program [34] | Curves fitness centers in New York City; Nutrition course took place at Columbia University Medical Center | Target goal to exercise 3 days/week for six months; nutrition course consisted of six 1-h weekly group sessions | Language Needs Assessment | Adherence to the exercise program was monitored using computerized Curves attendance logs. Attendance was recorded at the nutrition education sessions, and telephone make-up sessions were tracked. | Good | Anthropometric measurements showed that the intervention group lost an average of 3.3% (±3.5%) of total body weight at 6 months, which corresponds to an absolute weight loss of 2.9 (±3.1) kg. The control group lost an average of 1.8% (±2.9%) of body weight, which corresponds to an absolute weight loss of 1.4 (±2.5) kg. There were no changes in metabolic biomarkers using intent-to-treat analysis, as assessed by serum testing. |

| Swimming-based physical activity promotion program [35] | 12 practice sites in Guadeloupe | 2 sessions per week for 10 weeks | Language Culture Needs Assessment | Not reported | Fair | Self-reported quality of life survey showed no significant change (p > 0.05) for all domains, including physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment. A self-reported physical activity survey showed significant improvement in physical activity (p < 0.001). |

| Program Feature | Diet | Diabetes | Physical Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tailoring of the program | |||

| Language or literacy tailoring: the program is tailored to the specific populations’ language or literacy level | 0.50 | −0.50 | 0.25 |

| Cultural tailoring: the program is tailored to the specific populations’ culture * | 0.35 | −0.35 | −0.05 |

| Needs assessment: the program assesses each participant’s individual needs formally for the design of the content | 0.17 | −0.17 | 0.33 |

| Program provider | |||

| Health care provider: delivered by a licensed health care provider * | −0.17 | 0.67 | −0.33 |

| Community-educator-led: delivered by trained nonhealthcare personnel * | −0.35 | −0.10 | 0.05 |

| Multidisciplinary team: delivered by two or more types of program providers * | 0.63 | −0.63 | 0.88 |

| Research staff: delivered by a trained research team * | 0.63 | −0.63 | −0.25 |

| Setting of the program | |||

| Primary care: delivered in the primary care system (e.g., family practice) * | −0.17 | 0.67 | −0.33 |

| Community-based: delivered outside of the healthcare setting (e.g., local church) * | 0.10 | −0.55 | 0.50 |

| Hospital-based: delivered in a clinic affiliated with a hospital * | −0.50 | 0.50 | −0.25 |

| Home: delivered at the residence of the subject * | 0.07 | −0.07 | −0.29 |

| Mode of program delivery | |||

| Individual: delivered individually, one-on-one | −0.10 | 0.10 | −0.05 |

| Group: delivered to a group of participants | 0.17 | −0.17 | 0.33 |

| Format of program | |||

| Face-to-face: delivered face-to-face with participants | −0.63 | 0.63 | 0.25 |

| Online: delivered through the internet * | 0.63 | −0.63 | −0.25 |

| Written Literature: delivered through written material (e.g., handbook) * | 0.63 | 0.50 | −0.25 |

| Telephone: delivered by phone * | −0.50 | 0.50 | −0.25 |

| Audio–Visual: delivered through educational videos * | 0.83 | −0.33 | −0.33 |

| Method/type of instruction | |||

| Interactive/discussion: education provided was delivered mainly by an interactive format * | 0.55 | −0.10 | 0.05 |

| Didactic teaching: education provided was delivered mainly by lectures | −0.10 | 0.55 | −0.05 |

| Behavioral: focuses on behavior-related tasks (e.g., exercise, diet) using behavior-based programs | −0.07 | 0.07 | 0.29 |

| Self-management education: comprehensive education that focuses on developing diabetes knowledge and patients’ ability to self-manage their diabetes * | 0.07 | 0.57 | −0.29 |

| Family support: encourages family members to get involved in attending the session * | −0.50 | −0.63 | 0.88 |

| Feedback: interventionists provide specific feedback for participants to aid in monitoring aspects of their own management (e.g., diet and exercise feedback) * | 0.63 | 0.50 | −0.25 |

| Diaries and Reports: a specific type of feedback activity, where food diaries, physical activity logs, and self-management of blood glucose logs were used by participants to record specific components * | −0.57 | 0.57 | −0.29 |

| Duration of the program | |||

| Short Duration: length of the program is less than 6 months * | 0.55 | −0.55 | 0.05 |

| Long Duration: length of the program is equal to or more than 6 months | −0.55 | 0.55 | −0.05 |

| Intensity of the program | |||

| Low Intensity: less than 2 sessions per month * | 0.55 | −0.10 | −0.40 |

| High Intensity: equal to or more than 2 sessions per month | −0.55 | 0.10 | 0.40 |

| Content of the program | |||

| Diet: the program teaches diet-related content | 0.57 | 0.07 | −0.36 |

| Physical activity: the program teaches exercise-related content | −0.33 | 0.33 | 0.33 |

| Psychosocial: the program teaches psychosocial-related content * | 0.71 | −0.07 | −0.29 |

| Diabetes education: program is aimed at patients’ diabetes knowledge for specific diabetes management topics | −0.33 | 0.83 | −0.67 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hasan, M.; Singh, H.; Haffizulla, F. Culturally Sensitive Health Education in the Caribbean Diaspora: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1476. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041476

Hasan M, Singh H, Haffizulla F. Culturally Sensitive Health Education in the Caribbean Diaspora: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(4):1476. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041476

Chicago/Turabian StyleHasan, Mashtura, Harmandip Singh, and Farzanna Haffizulla. 2021. "Culturally Sensitive Health Education in the Caribbean Diaspora: A Scoping Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 4: 1476. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041476

APA StyleHasan, M., Singh, H., & Haffizulla, F. (2021). Culturally Sensitive Health Education in the Caribbean Diaspora: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4), 1476. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041476