Policy Inertia on Regulating Food Marketing to Children: A Case Study of Malaysia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

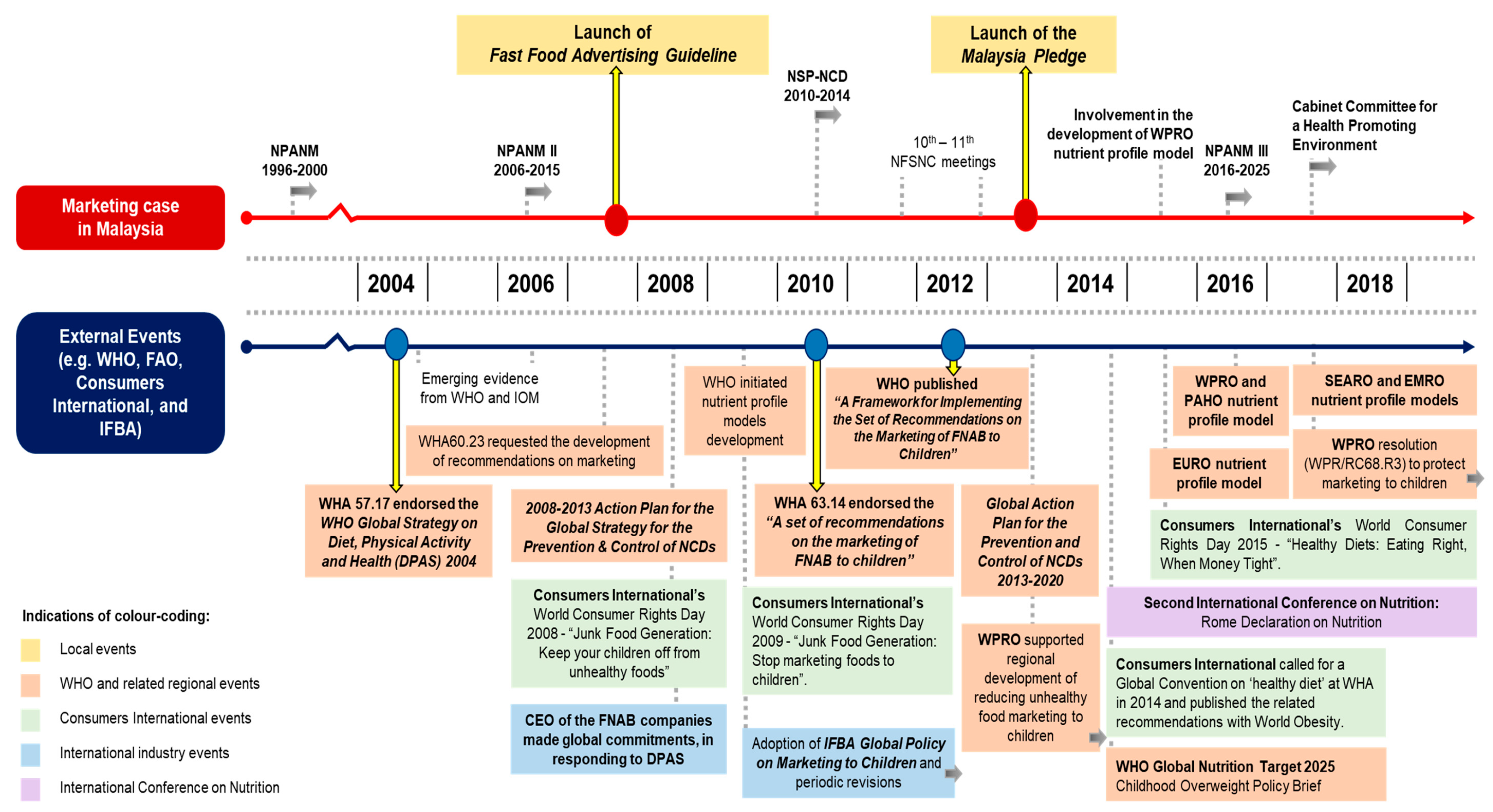

3.2. Historical Mapping of the Food Marketing Policy Processes

3.3. Key Themes

3.3.1. Policy Commitment

“The Ministry of Health would not be able to [either] monitor or enforce… not at the capacity to monitor… [hence] they [i.e., the advertising industry] took up the role….”(Government stakeholder on development and implementation).

“I [first] ‘assumed’ it would be based on some kind of legislation... But, [later it was] the Pledge...”(Civil society stakeholder on development).

“The Malaysian intention was [to] implement the resolution [of World Health Assembly (WHA) 63.14], but along the way, it became voluntary… I used the word “Executive Decision” … … the [authority] did not want to make any major shift… [despite] the scientific evidence is there… it is more on political will... There was no interest.”(Government stakeholder on development and implementation).

“Not all companies have to be in… some can be quite sensitive… … we [SME] are doing more [on] reformulation first… we can join the Pledge, [but] after this.”(Industry stakeholder on implementation).

“I did not see any NGO [non-government organisation] in Malaysia that is strong…”(Government stakeholder on implementation).

“A major global issue [where the] Consumers International had a junk food generation campaign [and] World Consumer Rights Day… Apart from that, [no] sustained campaigns.”(Civil society stakeholder on implementation).

“There was a specific recommendation [from] the WHA’s Resolution. We had the guidance from the WHO documents… looking at whatever WHO is recommending... [like] ‘peak hours’…”(Government stakeholder on development).

3.3.2. Policy Governance

“Do not have anywhere to park [the legislation] … same for Fast Food [Advertising Guideline] … under the Food Act [or Food Regulations], the mandate is more on the health hazard, food safety and also fraud... unhealthy food is not under [the purview of this] mandate... If the foods can be sold in the market… [it is] contradictory [to] restrict the selling of that foods [using the existing legislations] … [including the Ministry of Communication, the proposed legislation] also cannot park under their [regulations].”(Government stakeholder on development, implementation and future plans).

“No [government-led monitoring for the Fast Food Advertising Guideline] … … the Malaysia Pledge… it is an industry driven [monitoring].”(Government stakeholder on implementation).

“… the [Fast Food Advertising] Guideline… nobody tells me, is it done or not… … [and also] the Pledge, I asked [industry group and] government, both sides... “Is it working or not?”. I do not see that [i.e., any compliance report being published], until today.”(Civil society stakeholder on implementation).

3.3.3. External to Policy Organisation

“[Agency A] can do whatever... They do not engage us [Agency B] or industries per se... when [Agency A] chaired, suddenly, “It is a law”. I mean, where is the Committee? Who decided on that?”(Government stakeholder on development and implementation).

“For a start… a few years, do that Pledge and see how it looks. [See if it is] difficult [to be] compliant...”(Civil society stakeholder on development).

“It is based on the consensus meeting… [the stakeholders] agreed with 12 [years old for the Pledge] … in between the [fast food advertising] guideline up to 10 [years old and the] Children’s Act up to 14 [years old].”(Government stakeholder on development).

3.3.4. Industry

“Initially, they [fast food industry] did not agree... their reason is why [are we] blaming them… in terms of obesity… maybe other factors… how about the mamak foods [i.e., local Tamil Muslim food sector] and all the other things?”(Government stakeholder on development).

Information and messaging strategy: “I can only “assume” what has happened... but I do not have any evidence… [they are] working in the background… direct or just lobbying the [relevant] Ministries using their counter-arguments… very powerful lobbying by the industry.”(Government and civil society stakeholders on development).

Policy substitution strategy: “[as] we [the government] could not implement an aggressive manner at that time… they [industries] came forward to make the [Pledge] proposal.”(Government stakeholder on development).

Constituency building strategy: “… lobbying [the] professional associations… [where their] opinions are keen towards the industry.”(Government stakeholder on development).

“… if a company supports [professional organisation’s] activities… our views can be compromised. That’s definitely not so…”(Civil society stakeholder).

versus

“No company will want to sponsor you without a return of investment... any sponsorship in cash or in-kind, it does have impact on bodies [to] behave towards the industries...”(Government stakeholder).

“The Malaysia Pledge… industries were very much supportive… [some companies] had their counterparts in other countries [that were] also involved in [such a] Pledge. So, they moved [towards that].”(Industry stakeholder on development).

3.3.5. Policy Specific Issue

“At that time… one of the questions is “what is fast food?”… there is no definition internationally… … [for the Pledge], “How [do you] categorise foods?... No guideline at that time … to combine [different nutrient] profiles from companies [was also] very challenging... Which [television] programmes [to be controlled]? How do [you] define children?”(Government and civil society stakeholders on development).

“The nutrient profiling... the challenge is to set criteria…. Along the way, [we referred to] WHO reports... but, whether we can use [them] for Malaysian foods or not... There is still a question…”(Government stakeholder on future plans).

“… this is not a law [for Fast Food Advertising Guideline], but like CSR [Corporate Social Responsibility] … no law [to] take them to court [for non-compliance] … … [Likewise]… no confidence in Pledge… sceptical about self-regulation.”(Government and civil society stakeholders on development).

“[Fast food advertising] guideline… too limited [in] scope [and] very small niche… … [the Pledge] is voluntary… [causing] a double standard... not many industries [participated and] those who signed, you need to be good boys... no urgency in the implementation of the Pledge with other industries... … That’s why it is quite hard... to push for more than what [is] being written [and] to control.”(Government stakeholder on implementation).

3.3.6. Opportunistic Advantages

“WHO Guideline—restriction on marketing of foods to children… was the drive, and also Malaysia wanted to fulfil that pledge to WHO…”(Civil society stakeholder on development).

3.4. Recommendations

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Noncommunicable Diseases. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- World Obesity Federation. Obesity: Missing the 2025 Global Targets—Trends, Costs and Country Reports. 2020. Available online: http://s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/wof-files/WOF_Missing_the_2025_Global_Targets_Report_FINAL_WEB.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2021).

- The World Bank Group. Malaysia. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/country/malaysia (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Institute for Public Health (IPH). Fact Sheet National Health and Morbidity Survey 2019: Non-Communicable Diseases, Healthcare Demand, and Health Literacy; Institute for Public Health, Ministry of Health: Shah Alam, Malaysia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). Data from: GBD Compare Data Visualization (Cause and Risk, DALYs—Malaysia—GBD 2017). 2020. Available online: http://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare (accessed on 5 December 2020).

- Monteiro, C.A.; Moubarac, J.C.; Levy, R.B.; Canella, D.S.; Louzada, M.L.D.C.; Cannon, G. Household availability of ultra-processed foods and obesity in nineteen European countries. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nardocci, M.; Polsky, J.; Moubarac, J.C. How Ultra-Processed Foods Affect Health in Canada; Transnut, Department of Nutrition, University of Montreal: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Srour, B.; Fezeu, L.K.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Allès, B.; Méjean, C.; Andrianasolo, R.M.; Chazelas, E.; Deschasaux, M.; Hercberg, S.; Galan, P.; et al. Ultra-processed food intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: Prospective cohort study (NutriNet-Santé). BMJ 2019, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vandevijvere, S.; Jaacks, L.M.; Monteiro, C.A.; Moubarac, J.C.; Girling-Butcher, M.; Lee, A.C.; Lee, A.C.; Pan, A.; Bentham, J.; Swinburn, B. Global trends in ultraprocessed food and drink product sales and their association with adult body mass index trajectories. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinburn, B.A.; Kraak, V.I.; Allender, S.; Atkins, V.J.; Baker, P.I.; Bogard, J.R.; Brinsden, H.; Calvillo, A.; de Schutter, O.; Devarajan, R.; et al. The Global Syndemic of Obesity, Undernutrition, and Climate Change: The Lancet Commission report. Lancet 2019, 393, 791–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.H.; Kelly, B.; Se, C.H.; Chinna, K.; Jamil, S.M.; Shanthi, K.; Ismail, M.N.; Karupaiah, T. Obesogenic television food advertising to children in Malaysia: Sociocultural variations. Glob. Health Action 2014, 7, 25169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Baldwin, H.J.; Freeman, B.; Kelly, B. Like and share: Associations between social media engagement and dietary choices in children. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 3210–3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beckerman, J.P.; Alike, Q.; Lovin, E.; Tamez, M.; Mattei, J. The development and public health implications of food preferences in children. Front. Nutr. 2017, 4, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boyland, E.J.; Nolan, S.; Kelly, B.; Tudur-Smith, C.; Jones, A.; Halford, J.C.G.; Robinson, E. Advertising as a cue to consume: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of acute exposure to unhealthy food and non-alcoholic beverage advertising on intake in children and adults. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 103, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.H.; Kelly, B.; Se, C.H.; Sahathevan, S.; Chinna, K.; Noor, M.I.; Karupaiah, T. Reading the mind of children in response to food advertising: A cross-sectional study of Malaysian schoolchildren’s attitudes towards food and beverages advertising on television. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scully, M.; Wakefield, M.; Niven, P.; Chapman, K.; Crawford, D.; Pratt, I.S.; Baur, L.A.; Flood, V.; Morley, B.; NaSSDA Study Team. Association between food marketing exposure and adolescents’ food choices and eating behaviors. Appetite 2012, 58, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, R.; Kelly, B.; Yeatman, H.; Boyland, E. Food marketing influences children’s attitudes, preferences and consumption: A systematic critical review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization (WHO). A Framework for Implementing the Set of Recommendations on the Marketing of Foods and Non-Alcoholic Beverages to Children; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Report of the Commission on Ending Childhood Obesity: Implementation Plan. 2017. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA70/A70_31-en.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2020).

- UNICEF. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. n.d. Available online: https://downloads.unicef.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/UNCRC_summary-1_1.pdf (accessed on 27 February 2021).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Nutrition Policy Review 2016–2017: Country Progress in Creating Enabling Policy Environments for Promoting Healthy Diets and Nutrition; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific (WPRO). Regional Action Framework on Protecting Children from the Harmful Impact of Food Marketing in the Western Pacific; WPRO: Manila, Philippines, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Food Safety and Quality Division (FSQD). Garis Panduan Pengiklanan dan Pelabelan Maklumat Pemakanan Makanan Segera. n.d. Available online: http://fsq.moh.gov.my/v6/xs/dl.php?filename=320c4443c5c9b60b44dbbf3a76d264dd.pdf (accessed on 9 April 2019).

- International Food & Beverage Alliance (IFBA). Malaysian Food and Beverage Industry’s “Responsible Advertising to Children” Initiative (The Malaysia Pledge). n.d. Available online: https://ifballiance.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/MALAYSIA_PLEDGE_FINAL_.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- Ng, S.H.; Swinburn, B.; Kelly, B.; Vandevijvere, S.; Yeatman, H.; Ismail, M.N.; Karupaiah, T. Extent of implementation of food environment policies by the Malaysian Government: Gaps and priority recommendations. Public Health Nutr. 2018, 21, 3395–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. Food-Environment Policy Index (Food-EPI): Benchmarking Current Policies and Determining Priorities for Future Policies for the Malaysian Government 2016–2017. 2018. Available online: https://doi.org/10.17608/k6.auckland.8251361.v1 (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF). NOURISHING Framework—Restrict Food Advertising and Other Forms of Commercial Promotion. n.d. Available online: https://policydatabase.wcrf.org/level_one?page=nourishing-level-one#step2=3 (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Galbraith-Emami, S.; Lobstein, T. The impact of initiatives to limit the advertising of food and beverage products to children: A systematic review. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 960–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatier, P.A.; Jenkins-Smith, H.C. The advocacy coalition framework: An assessment. In Theories of the Policy Process, 1st ed.; Sabatier, P.A., Ed.; Westview: Boulder, CO, USA, 1999; pp. 117–166. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb, R.; Ross, J.K.; Ross, M.H. Agenda building as a comparative political process. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1976, 70, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Breton, E.; Richard, L.; Gagnon, F.; Jacques, M.; Bergeron, P. Coalition advocacy action and research for policy development. In Health Promotion and the Policy Process; Clavier, C., de Leeuw, E., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lemieux, V. Les Coalitions: Liens, Transactions et Controles; Pressess Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, S.H.; Kelly, B.; Yeatman, H.; Swinburn, B.; Karupaiah, T. Tracking progress from policy development to implementation: A case study on adoption of mandatory regulation for nutrition labelling in Malaysia. Nutrients 2021, 13, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- University College London. The Constitution Unit: Malaysia—International Focus (Background and Recent History). n.d. Available online: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/constitution-unit/research/research-archive/foi-archive/international-focus/malaysia (accessed on 7 January 2020).

- Ministry of Health (MOH). Code of Ethics for The Marketing of Infant Foods and Related Products; Nutrition Division Section, Family Health Development Division, Ministry of Health: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2008.

- Phulkerd, S.; Sacks, G.; Vandevijvere, S.; Worsley, A.; Lawrence, M. Barriers and potential facilitators to the implementation of government policies on front-of-pack food labeling and restriction of unhealthy food advertising in Thailand. Food Policy 2017, 71, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, E.; Thow, A.M.; Bell, C.; Engelhardt, K.; Gamolo-Naliponguit, E.C.; Go, J.J.; Sacks, G. Implementation lessons for school food policies and marketing restrictions in the Philippines: A qualitative policy analysis. Glob. Health 2018, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veale, S.; Schilling, K. Talking History Oral History Guidelines; Department of Environment & Conservation: Hurstville, NSW, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- National Heritage Board. The Heritage Researcher: A Practical Guide to Action—Oral History Interviews. 2019. Available online: https://www.nhb.gov.sg/-/media/nhb/files/resources/oral-history-interview-guidebook_content.pdf?la=en (accessed on 8 January 2020).

- Mialon, M.; Swinburn, B.; Sacks, G. A proposed approach to systematically identify and monitor the corporate political activity of the food industry with respect to public health using publicly available information. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leech, N.L.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Beyond Constant Comparison Qualitative Data Analysis: Using NVivo. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2011, 26, 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ng, S.H.; Kelly, B.; Yeatman, H.; Sankara Narayanan, S.; Karupaiah, T. Challenges and Enablers in the Implementation of Government-Led Food Environment Policies: A Systematic Review. 2021. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?RecordID=115034 (accessed on 2 June 2021).

- Khor, G.L.; Gan, C.Y. Trends and dietary implications of some chronic non-communicable diseases in peninsular Malaysia. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 1992, 1, 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- National Coordinating Committee on Food and Nutrition (NCCFN). National Plan of Action for Nutrition of Malaysia (1996–2000); National Coordinating Committee on Food and Nutrition, Ministry of Health: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1995.

- Noor, M.I. The nutrition and health transition in Malaysia. Public Health Nutr. 2002, 5, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ahmad, A. Country Briefing Paper—Women in Malaysia. 1998. Available online: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/institutional-document/32552/women-malaysia.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2020).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). Food Marketing to Children and Youth: Threat or Opportunity; IOM: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Marketing Food to Children: The Global Regulatory Environment; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). The Extent, Nature and Effects of Food Promotion to Children: A Review of the Evidence—Technical Paper Prepared for the World Health Organization; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- National Coordinating Committee on Food and Nutrition (NCCFN). National Plan of Action for Nutrition of Malaysia (2006–2015); National Coordinating Committee on Food and Nutrition, Ministry of Health: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2006.

- Tee, E.S. Keeping an Eye on Fast Foods. The Star. 2008. Available online: https://www.thestar.com.my/lifestyle/health/2008/02/17/keeping-an-eye-on-fast-foods (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- World Health Organization (WHO). Sixtieth World Health Assembly (14–23 May 2007): Resolutions and Decisions Annexes; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). 2008–2013 Action Plan for the Global Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Sixty-Third World Health Assembly (17–21 May 2010): Resolutions and Decisions Annexes; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Set of Recommendations on the Marketing of Foods and Non-Alcoholic Beverages to Children; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Nutrient Profiling—Report of a WHO/IASO Technical Meeting, London, United Kingdom 4–6 October 2010; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Nutrition Targets 2025: Childhood Overweight Policy Brief. 2014. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/665596/retrieve (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific (WPRO). Informal Consultation on Reducing the Harmful Impact on Children of Marketing Foods, Beverages, Tobacco and Alcohol, Manila, Philippines, 25–26 September 2013: Meeting Report. 2014. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/208783/RS_2013_GE_42_PHL_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 13 January 2020).

- Consumer Affairs Commission (CAC). World Consumer Rights Day Fact Sheet—Stemming the Upward Trend in Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) by Tackling Unhealthy Diets. 2015. Available online: https://www.consumeraffairsjamaica.gov.jm/portal/index.php?option=com_phocadownload&view=category&download=61:world-consumer-rights-day-2015-fact-sheet&id=5:consumer-advice&Itemid=311 (accessed on 13 January 2020).

- International Food & Beverage Alliance (IFBA). A Global Commitment to Action on the Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health (Letter). 2008. Available online: https://ifballiance.org/uploads/media/59de14cc5ce7f.pdf (accessed on 13 January 2020).

- International Food & Beverage Alliance (IFBA). Five Commitments in Five Years Review of Progress 2008–2013; IFBA: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health (MOH). National Strategic Plan for Non-Communicable Disease (NSPNCD): Medium Term Strategic Plan to Further Strengthen the Cardiovascular Diseases & Diabetes Prevention & Control Program in Malaysia (2010–2014); NCD Section, Disease Control Division, Ministry of Health: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2010.

- Ministry of Health (MOH). Annual Report 2012: Ministry of Health Malaysia; MOH: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2012.

- Federation of Malaysian Manufacturers (FMM). Malaysian Food and Beverage Industry Commits To Combating Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs). 2015. Available online: https://www.fmm.org.my/Press_Releases-@-Malaysian_Food_and_Beverage_Industry_Commits_To_Combating_Non-Communicable_Diseases_(NCDs)_in_Partnership_with_the_Government.aspx (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; World Health Organization. Second International Conference on Nutrition—Conference Outcome Document: Rome Declaration on Nutrition (Rome, 19–21 November 2014). 2014. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-ml542e.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Consumers International; World Obesity Federation. Recommendations towards a Global Convention to Protect and Promote Healthy Diets. 2014. Available online: https://www.consumersinternational.org/media/2211/recommendations-for-a-convention-on-healthy-diets-low-res-for-web.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2020).

- Consumers International. World Consumer Rights Day 2015—Healthy Diets. n.d. Available online: https://www.consumersinternational.org/what-we-do/world-consumer-rights-day/wcrd-2015-healthy-diets (accessed on 11 January 2020).

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the East Mediterranean (EMRO). Nutrient Profile Model for the Marketing of Food and Non-Alcoholic Beverages to Children in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region; EMRO: Cairo, Egypt, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe (EURO). WHO Regional Office for Europe Nutrient Profile Model; EURO: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). Pan American Health Organization Nutrient Profile Model; PAHO: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia (SEARO). WHO Nutrient Profile Model for South-East Asia Region; SEARO: New Delhi, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific (WPRO). WHO Nutrient Profile Model for the Western Pacific Region: A Tool to Protect Children from Food Marketing; WPRO: Manila, Philippines, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific (WPRO). Western Pacific Regional Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases; WPRO: Manila, Philippines, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific (WPRO). Action Plan to Reduce the Double Burden of Malnutrition in the Western Pacific Region (2015–2020); WPRO: Manila, Philippines, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific (WPRO). Biregional Workshop on Restricting the Marketing of Foods and Non-Alcoholic Beverages to Children in the Western Pacific and South-East Asia (1–4 December 2015: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia); WPRO: Manila, Philippines, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific (WPRO). Technical Meeting on the Regional Adaptation of the WHO Nutrient Profile Model to the Western Pacific Region (19–21 October 2015: Manila, Philippines); WPRO: Manila, Philippines, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific (WPRO). Regional Workshop on Regulating the Marketing and Sale of Foods and Non-Alcoholic beverages at Schools (1–3 June 2016: Manila, Philippines); WPRO: Manila, Philippines, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific (WPRO). Resolution—Protecting Children from the Harmful Impact of Food Marketing (WPR/RC68.R3). 2017. Available online: https://iris.wpro.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665.1/13719/WPR-RC068-Res03-2017-en.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2020).

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific (WPRO). Experts Consultation to Inform the Development of a Draft Regional Action Framework on Protecting Children from the Harmful Impact of Food Marketing: 2020–2030 (5–7 December 2018: Manila, Philippines); WPRO: Manila, Philippines, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific (WPRO). Member States Consultation on the Draft Regional Action Framework on Protecting Children from the Harmful Impact of Food Marketing 2020–2030 (26–28 March 2019: Manila, Philippines); WPRO: Manila, Philippines, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- National Coordinating Committee on Food and Nutrition (NCCFN). National Plan of Action for Nutrition of Malaysia (NPANM III) 2016–2025; National Coordinating Committee on Food and Nutrition, Ministry of Health: Putrajaya, Philippines, 2016.

- Arumugam, T. Policies to Promote a Healthier Nation. New Straits Times. 2017. Available online: https://www.nst.com.my/news/exclusive/2017/12/318178/policies-promote-healthier-nation (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Chung, A.; Shill, J.; Swinburn, B.; Mavoa, H.; Lawrence, M.; Loff, B.; Crammond, B.; Sacks, G.; Allender, S.; Peeters, A. An analysis of potential barriers and enablers to regulating the television marketing of unhealthy foods to children at the state government level in Australia. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boyland, E.J.; Harris, J.L. Regulation of food marketing to children: Are statutory or industry self-governed systems effective? Public Health Nutr. 2017, 20, 761–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ronit, K.; Jensen, J.D. Obesity and industry self-regulation of food and beverage marketing: A literature review. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 68, 753–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belinda, F.C.L.; Asnira Zolkepli, I. A content analysis of appeals in food advertisements for children on online tv streaming. SEARCH J. Media Commun. Res. 2019, 11, 113–136. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul Razak, Z. Effects of Media Literacy Education about Television Food Advertising on School Children. 2015. Available online: http://ir.uitm.edu.my/id/eprint/15306/ (accessed on 22 December 2019).

- Ng, S.H.; Sacks, G.; Kelly, B.; Yeatman, H.; Robinson, E.; Swinburn, B.; Vandevijvere, S.; Chinna, K.; Ismail, M.N.; Karupaiah, T. Benchmarking the transparency, comprehensiveness and specificity of population nutrition commitments of major food companies in Malaysia. Global Health 2020, 16, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, G.; Robinson, E.; Cameron, A.J.; Vanderlee, L.; Vandevijvere, S.; Swinburn, B. Benchmarking the nutrition-related policies and commitments of major food companies in Australia, 2018. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consumers Association of Penang (CAP). Protecting Our Children from Unhealthy Food Advertising: Needs More Than a Pledge. 2013. Available online: https://consumer.org.my/protecting-our-children-from-unhealthy-food-advertising-needs-more-than-a-pledge/ (accessed on 29 August 2019).

- Federation of Malaysian Consumers Associations (FOMCA). Malaysian Consumers Wishlist for the 13th General Election. 2012. Available online: http://www.konsumerkini.net.my/v1/images/stories/pdf/wishlist_eng.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- Kementerian Perdagangan Dalam Negeri dan Hal Ehwal Pengguna (KPDNHEP). Buletin Pengguna—Hari Pengguna Sedunia 2008 Kempen Global Untuk Menghentikan Pemasaran Makanan Tidak Berkhasiat Kepada Kanak-Kanak (Mac 2009); KPDNHEP: Putrajaya, Philippines, 2009.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; Pan American Health Organization. Approval of A New Food Act in Chile: Process Summary—Entry into Force: June 2016; FAO: Rome, Italy; WHO: Santiago, Chile, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Barquera, S.; Campos, I.; Rivera, J.A. Mexico attempts to tackle obesity: The process, results, push backs and future challenges. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mialon, M.; Corvalan, C.; Cediel, G.; Scagliusi, F.B.; Reyes, M. Food industry political practices in Chile: “the economy has always been the main concern”. Global Health 2020, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cullerton, K.; Adams, J.; Forouhi, N.; Francis, O.; White, M. What principles should guide interactions between population health researchers and the food industry? Systematic scoping review of peer-reviewed and grey literature. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 1073–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Safeguarding against Possible Conflicts of Interest in Nutrition Programmes. 2017. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB142/B142_23-en.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 3 May 2020).

- FAO; WHO. Food Safety Legislation Science and Risk-Based Approaches to Harmonization—Food Safety Legislation in Malaysia. 2004. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/ad698e/ad698e.htm (accessed on 14 August 2021).

- Thow, A.M.; Swinburn, B.; Colagiuri, S.; Diligolevu, M.; Quested, C.; Vivili, P.; Leeder, S. Trade and food policy: Case studies from three Pacific Island countries. Food Policy 2010, 35, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsukait, R.; Bleich, S.; Wilde, P.; Singh, G.; Folta, S. Sugary drink excise tax policy process and implementation: Case study from Saudi Arabia. Food Policy 2020, 90, 101789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech-Larsen, T.; Aschemann-Witzel, J. A macromarketing perspective on food safety regulation: The Danish ban on trans-fatty acids. J. Macromark. 2012, 32, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Gleeson, D.; Barraclough, S. Australia’s Health Star Rating policy process: Lessons for global policy-making in front-of-pack nutrition labelling. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 75, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Human Development Index (HDI). n.d. Available online: http://hdr.undp.org/en/indicators/137506# (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Sisnowski, J.; Street, J.M.; Braunack-Mayer, A. Targeting population nutrition through municipal health and food policy: Implications of New York City’s experiences in regulatory obesity prevention. Food Policy 2016, 58, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Theme | Nature | Sub-Theme | Policy Process | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development | Implementation/Future Plans | |||

| Policy commitment | Barrier | Lack of resources | √ | √ |

| Barrier | Lack of political will | √ | √ | |

| Barrier | Implementer characteristics | X | √ | |

| Barrier | Lack of sustained efforts | X | √ | |

| Facilitator | Leadership | X | √ | |

| Facilitator | Resource availability or maximisation | √ | √ | |

| Policy governance | Barrier | Complexity | √ | √ |

| Barrier | Lack of monitoring | X | √ | |

| External to policy organisation | Barrier | Stakeholder relations | √ | √ |

| Facilitator | Stakeholder partnership or support | √ | X | |

| Industry | Barrier | Industry resistance | √ | X |

| Policy specific issue | Barrier | Technical challenges | √ | √ |

| Barrier | Policy characteristics | √ | √ | |

| Barrier | Non-mandatory | X | √ | |

| Opportunistic advantages | Facilitator | Policy window | √ | X |

| Recommendations | |

|---|---|

| 1. | Strong and proactive leadership to guard against political stagnation and commercial interests, and balancing public health interest to combat the influence of unhealthy food marketing to children. |

| 2. | World Trade Organization endorsement of WHO recommendations for the restriction of unhealthy food marketing to children. |

| 3. | Resource maximisation, particularly in using credible scientific evidence and providing education to all policy stakeholders (e.g., SME, broadcasters, advertisers and public). |

| 4. | A comprehensive regulatory framework including strict enforcement that links non-compliance to consequences. |

| 5. | Strengthening inter-ministerial collaboration (e.g., find solutions for governance complexity, set common objectives) and engaging with the key external stakeholders of food marketing policies (e.g., broadcasters and advertisers). |

| 6. | Mapping positions of NGO stakeholders with shared interests in restricting unhealthy food marketing to children and forming a pro-public health coalition with sustained advocacy actions. |

| 7. | Integration of sustained and transparent monitoring and evaluation systems, with the involvement of civil society and academia that pose none conflicts of interest. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ng, S.; Kelly, B.; Yeatman, H.; Swinburn, B.; Karupaiah, T. Policy Inertia on Regulating Food Marketing to Children: A Case Study of Malaysia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189607

Ng S, Kelly B, Yeatman H, Swinburn B, Karupaiah T. Policy Inertia on Regulating Food Marketing to Children: A Case Study of Malaysia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(18):9607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189607

Chicago/Turabian StyleNg, SeeHoe, Bridget Kelly, Heather Yeatman, Boyd Swinburn, and Tilakavati Karupaiah. 2021. "Policy Inertia on Regulating Food Marketing to Children: A Case Study of Malaysia" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 18: 9607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189607

APA StyleNg, S., Kelly, B., Yeatman, H., Swinburn, B., & Karupaiah, T. (2021). Policy Inertia on Regulating Food Marketing to Children: A Case Study of Malaysia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(18), 9607. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189607