Why Do Citizens Share COVID-19 Fact-Checks Posted by Chinese Government Social Media Accounts? The Elaboration Likelihood Model

Abstract

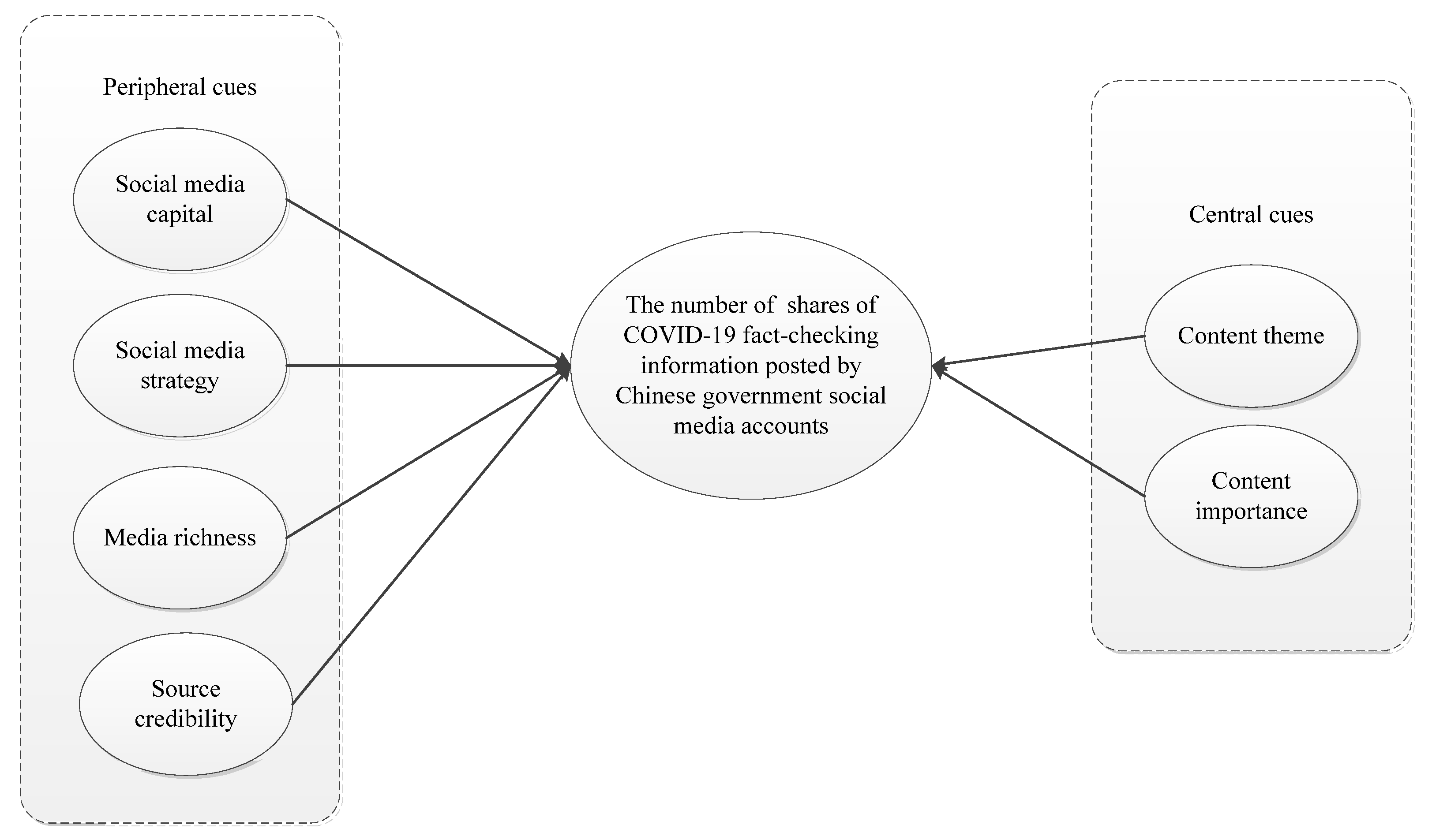

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Elaboration Likelihood Model

2.2. Research Hypotheses and Model

2.2.1. The Effect of Peripheral Cues on the Sharing of Fact-Checks

Social Media Capital

Social Media Strategy

Media Richness

Source Credibility

2.2.2. The Effect of Central Cues on the Sharing of Fact-Checking Information

Content Theme

Content Importance

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Operationalization of Variables

3.3. Inter-Coder Reliability and Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

4.2. Hypotheses Test

5. Discussion

5.1. Summary of Findings

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fleming, N. Coronavirus misinformation, and how scientists can help to fight it. Nature 2020, 583, 155–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennycook, G.; McPhetres, J.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, J.G.; Rand, D.G. Fighting COVID-19 Misinformation on Social Media: Experimental evidence for a scalable accuracy-nudge intervention. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J. Themes and evolution of misinformation during the early phases of the COVID-19 outbreak in China—An application of the crisis and emergency risk communication model. Front. Commun. 2020, 5, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Chan, C. A cross-national diagnosis of infodemics: Comparing the topical and temporal features of misinformation around COVID-19 in China, India, the US, Germany and France. Online Inf. Rev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, L. COVID-19: The medium is the message. Lancet 2020, 395, 942–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.-J.; Shin, S.Y. Mediated misinformation: Questions answered, more questions to ask. Am. Behav. Sci. 2021, 65, 259–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowsky, S.; Ecker, U.K.H.; Cook, J. Beyond misinformation: Understanding and coping with the “Post-Truth” Era. J. Appl. Res. Mem. Cogn. 2017, 6, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, W.; Ma, Y.; Wu, T.; Dai, Y.; Chen, X.; Braunstein, L.A. Containing misinformation spreading in temporal social networks. Chaos 2019, 29, 123131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Larson, H.J. Blocking information on COVID-19 can fuel the spread of misinformation. Nature 2020, 580, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, L.; Yin, J.; Song, Y. An exploration of rumor combating behavior on Social Media in the context of social crises. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 58, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amazeen, M.A.; Vargo, C.J.; Hopp, T. Reinforcing attitudes in a gatewatching news era: Individual-level antecedents to sharing fact-checks on Social Media. Commun. Monogr. 2019, 86, 112–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ceron, W.; de-Lima-Santos, M.-F.; Quiles, M.G. Fake News agenda in the era of COVID-19: Identifying trends through fact-checking content. Online Soc. Netw. Media 2021, 21, 100116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luengo, M.; García-Marín, D. The performance of truth: Politicians, fact-checking journalism, and the struggle to tackle COVID-19 misinformation. Am. J. Cult. Sociol. 2020, 8, 405–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q.; Yuan, J.; Dong, M.; Yang, L.; Fielding, R.; Lam, W.W.T. Public engagement and government responsiveness in the communications about COVID-19 during the early epidemic stage in China: Infodemiology study on social media data. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e18796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burel, G.; Farrell, T.; Mensio, M.; Khare, P.; Alani, H. Co-spread of misinformation and fact-checking content during the Covid-19 pandemic. In Social Informatics, Proceedings of the 12th International Social Informatics Conference (SocInfo 2020), Pisa, Italy, 6–9 October 2020; Aref, S., Bontcheva, K., Braghieri, M., Dignum, F., Giannotti, F., Grisolia, F., Pedreschi, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; pp. 28–42.

- Chung, M.; Kim, N. When I learn the news is false: How fact-checking information stems the spread of fake news via third-person perception. Hum. Commun. Res. 2021, 47, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Featherstone, J.D.; Calabrese, C.; Wojcieszak, M. Effects of fact-checking social media vaccine misinformation on attitudes toward vaccines. Prev. Med. 2021, 145, 106408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guess, A.; Nyhan, B.; Reifler, J. Selective Exposure to Misinformation: Evidence from the Consumption of Fake News during the 2016 US Presidential Campaign. Eur. Res. Counc. 2018, 9, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, M.; Cha, C.; Singh, K.; Lima, G.; Ahn, Y.-Y.; Kulshrestha, J.; Varol, O. Prevalence of misinformation and factchecks on the COVID-19 pandemic in 35 countries: Observational infodemiology study. JMIR Hum. Factors 2021, 8, e23279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, N.; Cohen, J.; Holbert, R.L.; Morag, Y. Fact-checking: A meta-analysis of what works and for whom. Political Commun. 2020, 37, 350–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Thorson, K. Partisan selective sharing: The biased diffusion of fact-checking messages on Social Media. J. Commun. 2017, 67, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.G.; Chen, Z.F.; Tao, W.; Cathy Li, Z. Functional and emotional traits of corporate social media message strategies: Behavioral insights from S&P 500 Facebook data. Public Relat. Rev. 2019, 45, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhang, C. Sentiment, richness, authority, and relevance model of information sharing during social crises—The case of #MH370 tweets. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 89, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.; Cacioppo, J. Communication and Persuasion; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, J.; Hu, P.; Lai, K.K.; Chen, G. Determinants of users’ information dissemination behavior on social networking sites: An elaboration likelihood model perspective. Internet Res. 2018, 28, 393–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Min, C.; Zhang, W.; Wang, G.; Ma, X.; Evans, R. Unpacking the black box: How to promote citizen engagement through government Social Media during the COVID-19 crisis. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 110, 106380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.-Y.; Kearney, M.; Chang, S.-L. Comparative approaches to mis/disinformation | belief in or identification of false news according to the elaboration likelihood model. Int. J. Commun. 2021, 15, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, K.; Kim, T.T.; Karatepe, O.M.; Lee, G. An exploration of the factors influencing social media continuance usage and information sharing intentions among Korean travellers. Tour. Manag. 2017, 63, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Rodgers, K.; Lovrich, N.P. “We Are More Than Crime Fighters”: Social Media images of Police Departments. Police Q. 2018, 21, 544–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Min, C.; Zhang, W.; Ma, X.; Evans, R. Factors driving citizen engagement with government TikTok accounts during the COVID-19 pandemic: Model development and analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e21463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, G.D.; Guo, C. Social Media Capital: Conceptualizing the nature, acquisition, and expenditure of social media-based organizational resources. Int. J. Acc. Inf. Syst. 2020, 36, 100443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Q.; Fang, B.; He, W.; Hsieh, J.J.P.-A. Can social capital be transferred cross the boundary of the real and virtual worlds? An empirical investigation of Twitter. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2012, 13, 144–156. [Google Scholar]

- Syed, R.; Rahafrooz, M.; Keisler, J.M. What it takes to get retweeted: An analysis of software vulnerability messages. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 80, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.E. Retweeting in health promotion: Analysis of tweets about breast cancer awareness month. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 74, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meijer, A.; Thaens, M. Social Media strategies: Understanding the differences between North American police departments. Gov. Inf. Q. 2013, 30, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergel, I. The social media innovation challenge in the public sector. Inf. Polity 2012, 17, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mergel, I. Social media adoption and resulting tactics in the U.S. Federal Government. Gov. Inf. Q. 2013, 30, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Huang, X.; Bort, J. A multiplatform investigation of law enforcement agencies on Social Media. Inf. Polity 2017, 22, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Wu, Q. Understanding Interactions Between Municipal Police Departments and the Public on Twitter. In Transforming Digital Worlds; Chowdhury, G., McLeod, J., Gillet, V., Willett, P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Mossberger, K.; Wu, Y.; Crawford, J. Connecting citizens and local governments? Social Media and interactivity in major U.S. cities. Gov. Inf. Q. 2013, 30, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Gupta, S.; Huang, Y. Examining conversations between Police Agencies and the Public on Facebook. In Proceedings of the 19th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research: Governance in the Data Age, New York, NY, USA, 30 May 2018; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Idris, I.K. Government Social Media in Indonesia: Just Another Information Dissemination Tool. J. Komun. Malays. J. Commun. 2018, 34, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daft, R.L.; Lengel, R.H.; Trevino, L.K. Message equivocality, media selection, and manager performance: Implications for information systems. MIS Q. 1987, 11, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denktaş-Şakar, G.; Sürücü, E. Stakeholder engagement via Social Media: An analysis of third-party logistics companies. Serv. Ind. J. 2020, 40, 866–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.A.; Thelen, P.; Robinson, K.; Men, L.R. How do CEOs communicate on Twitter? A comparative study between Fortune 200 companies and top startup companies. Corp. Commun. 2019, 24, 532–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Xu, W. The more attacks, the more retweets: Trump’s and Clinton’s agenda setting on Twitter. Public Relat. Rev. 2018, 44, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brubaker, P.J.; Wilson, C. Let’s give them something to talk about: Global brands’ use of visual content to drive engagement and build relationships. Public Relat. Rev. 2018, 44, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-R.R.; Fu, J.S. How to be heard on microblogs? Nonprofit organizations’ follower networks and post features for information diffusion in China. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2016, 19, 978–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Yang, S.-U. Like, comment, and share on Facebook: How each behavior differs from the other. Public Relat. Rev. 2017, 43, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soboleva, A.; Burton, S.; Mallik, G.; Khan, A. ‘Retweet for a Chance To…’: An analysis of what triggers consumers to engage in seeded EWOM on Twitter. J. Mark. Manag. 2017, 33, 1120–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabate, F.; Berbegal-Mirabent, J.; Cañabate, A.; Lebherz, P.R. Factors influencing popularity of branded content in Facebook Fan Pages. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, M.; Dass, M.; Kumar, P. The impact of media richness on consumer information search and choice. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 87, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Kim, Y.; Dou, X.; Kumar, S. Promote physical activity among college students: Using media richness and interactivity in web design. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 41, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, M.; Reich, B. Social Media and Loneliness: Why an Instagram picture may be worth more than a thousand Twitter words. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 62, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidry, J.P.D.; Carlyle, K.E.; LaRose, J.G.; Perrin, P.; Messner, M.; Ryan, M. Using the health belief model to analyze Instagram posts about Zika for public health communications. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 179–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, N.; Han, H.; Koo, C. Adoption of travel information in user-generated content on Social Media: The moderating effect of social presence. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2015, 34, 902–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, F.J.; Russell, F.M. Civility, credibility, and health information: The impact of uncivil comments and source credibility on attitudes about vaccines. Public. Underst. Sci. 2019, 28, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, L.; Li, H. Determinants of information retweeting in microblogging. Internet Res. 2012, 22, 443–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedeoglu, B.B. Are information quality and source credibility really important for shared content on Social Media? The moderating role of gender. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 31, 513–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.-L.; Zhou, Z.; Yu, X. Predicting users’ willingness to diffuse healthcare knowledge in Social Media: A communicative ecology perspective? Inf. Technol. People 2019, 32, 1044–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, A.Y.K.; Tee, C.-Y.; Pang, A.; Lim, E.-P. The retransmission of rumor and rumor correction messages on Twitter. Am. Behav. Sci. 2017, 61, 707–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Raine, J.W. Why is there less public trust in local government than in central government in China? Int. J. Public Adm. 2016, 39, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Christensen, T. Government trust, social trust, and citizens’ risk concerns: Evidence from crisis management in China. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2019, 42, 383–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keib, K.; Himelboim, I.; Han, J.-Y. Important tweets matter: Predicting retweets in the #BlackLivesMatter talk on Twitter. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 85, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.J.; Lee, H. When do people verify and share health rumors on Social Media? The effects of message importance, health anxiety, and health literacy. J. Health Commun. 2019, 24, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdullah, N.A.; Nishioka, D.; Tanaka, Y.; Murayama, Y. User’s action and decision making of retweet messages towards reducing misinformation spread during disaster. J. Inf. Process. 2015, 23, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malyshkina, N.V.; Mannering, F.L.; Tarko, A.P. Markov switching negative binomial models: An Application to vehicle accident frequencies. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2009, 41, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mothafer, G.I.M.A.; Yamamoto, T.; Shankar, V.N. A Negative binomial crash sum model for time invariant heterogeneity in panel crash data: Some insights. Anal. Methods Accid. Res. 2017, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Ma, J.; Jiang, G. Social trust, rational behavior, and government microblogs’ dissemination: An empirical analysis based on text mining. J. China Soc. Sci. Tech. Inf. 2019, 9, 954–965. [Google Scholar]

- Hofer, M.; Aubert, V. Perceived bridging and bonding social capital on Twitter: Differentiating between followers and followees. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2013, 29, 2134–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Rui, H.; Whinston, A.B. Content sharing in a social broadcasting environment: Evidence from Twitter. MIS Q. 2014, 38, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feroz Khan, G.; Young Yoon, H.; Kim, J.; Woo Park, H. From e-government to social government: Twitter use by Korea’s central government. Online Inf. Rev. 2014, 38, 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allport, G.W.; Postman, L. The Psychology of Rumor; Henry Holt: Oxford, UK, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Burton-Jones, A.; Xu, D. Rumors on Social Media in Disasters: Extending Transmission to Retransmission. In Proceedings of the 18th Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems, Chengdu, China, 24–28 June 2014; p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.M. Where is my issue? The influence of news coverage and personal issue importance on subsequent information selection on the web. J. Broadcasting Electron. Media 2008, 52, 600–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Categories | Example Posts |

|---|---|

| Latest COVID-19 News | #Win the fight against the epidemic# Newly confirmed cases in Siping spread online as a rumor!! |

| Government Action towards COVID-19 | 【Fact-checks】Fake! The notice of the Shandong Provincial Department of Education on matters related to the start of the 2020 spring school is a rumor. |

| Pathology and Treatment of COVID-19 | Can zinc treat the new coronary pneumonia? Rumor! Don’t believe it! #The police will not retreat before the epidemic# #Public security in action to fight COVID-19# #fact-checking on Sina Weibo# |

| Social Conditions during COVID-19 | 【Urgently refute rumors! Ezhou citizens must not follow the trend to buy grain and oil!】 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRR | SE | IRR | SE | IRR | SE | |

| (Intercept) | 1.01 | 0.34 | 2.10 * | 0.78 | 57.14 *** | 4.03 |

| Peripheral cues | ||||||

| Social media capital | 1.26 *** | 0.02 | 1.39 *** | 0.03 | ||

| Social media strategy (Reference group: Push) | ||||||

| Pull | 1.35 * | 0.19 | 5.19 *** | 0.91 | ||

| Networking | 2.65 *** | 0.66 | 2.14 * | 0.69 | ||

| Source credibility | 2.24 ** | 0.59 | 0.84 | 0.28 | ||

| Media richness | 1.65 *** | 0.19 | 0.90 | 0.12 | ||

| Central cues | ||||||

| Content theme (Reference group: Latest COVID-19 News) | ||||||

| Government Action towards COVID-19 | 0.75 ** | 0.07 | 0.55 *** | 0.06 | ||

| Pathology and Treatment of COVID-19 | 0.89 | 0.19 | 0.75 | 0.18 | ||

| Social Conditions during COVID-19 | 2.18 *** | 0.43 | 2.12 ** | 0.46 | ||

| Content importance | 32.94 *** | 5.62 | 41.67 *** | 7.88 | ||

| Log likelihood | −3898.87 | −4201.54 | −4044.54 | |||

| Pseudo R2(%) | 10.26 | 3.30 | 7.21 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Evans, R.; Min, C. Why Do Citizens Share COVID-19 Fact-Checks Posted by Chinese Government Social Media Accounts? The Elaboration Likelihood Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10058. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910058

Chen Q, Zhang Y, Evans R, Min C. Why Do Citizens Share COVID-19 Fact-Checks Posted by Chinese Government Social Media Accounts? The Elaboration Likelihood Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(19):10058. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910058

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Qiang, Yangyi Zhang, Richard Evans, and Chen Min. 2021. "Why Do Citizens Share COVID-19 Fact-Checks Posted by Chinese Government Social Media Accounts? The Elaboration Likelihood Model" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 19: 10058. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910058

APA StyleChen, Q., Zhang, Y., Evans, R., & Min, C. (2021). Why Do Citizens Share COVID-19 Fact-Checks Posted by Chinese Government Social Media Accounts? The Elaboration Likelihood Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(19), 10058. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph181910058