A Holistic Approach of Personality Traits in Medical Students: An Integrative Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

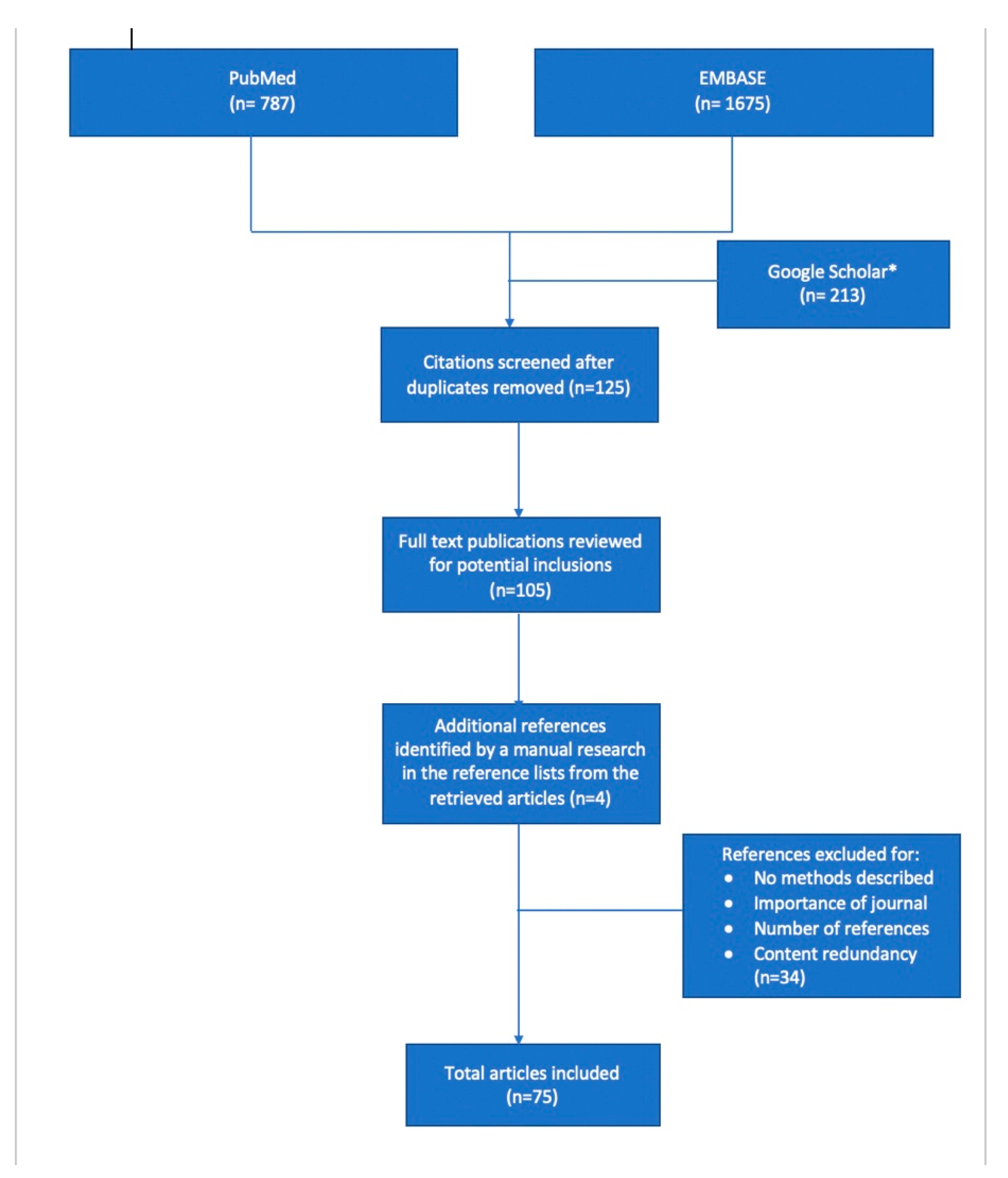

2. Literature Search

3. Personality Traits in Medical Students—The Core of the Doctor–Patient Relationship

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guilera, T.; Batalla, I.; Forné, C.; Soler-González, J. Empathy and Big Five Personality Model in Medical Students and Its Relationship to Gender and Specialty Preference: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Wheelwright, S. The Empathy Quotient: An Investigation of Adults with Asperger Syndrome or High Functioning Autism, and Normal Sex Differences. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2004, 34, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulzer, S.H.; Feinstein, N.W.; Wendland, C.L. Assessing Empathy Development in Medical Education: A Systematic Review. Med. Educ. 2016, 50, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hojat, M.; Gonnella, J.S. Eleven Years of Data on the Jefferson Scale of Empathy-Medical Student Version (JSE-S): Proxy Norm Data and Tentative Cutoff Scores. Med. Princ. Pract. Int. J. Kuwait Univ. Health Sci. Cent. 2015, 24, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, M. Which Personality Traits Have Favourable Impact on Psychological Health during Stressful Condition? Educ. Med. J. 2018, 10, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kwon, O.Y.; Park, S.Y. Specialty Choice Preference of Medical Students According to Personality Traits by Five-Factor Model. Korean J. Med. Educ. 2016, 28, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T. Reinterpreting the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator from the Perspective of the Five-Factor Model of Personality. J. Personal. 1989, 57, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, C.; Lachmann, H.; Kalén, S.; Ponzer, S.; Mellstrand Navarro, C. Personality and Learning Styles in Relation to Attitudes towards Interprofessional Education: A Cross-Sectional Study on Undergraduate Medical Students during Their Clinical Courses. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derish, P.A.; Annesley, T.M. How to Write a Rave Review. Clin. Chem. 2011, 57, 388–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Du Prel, J.-B.; Röhrig, B.; Blettner, M. Critical Appraisal of Scientific Articles: Part 1 of a Series on Evaluation of Scientific Publications. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2009, 106, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamannaeifar, M.; Mansourinik, A. The Relationship between Personality Characteristics, Social Support and Life Satisfaction with University Students’ Academic Performance. Q. J. Res. Plan. High. Educ. 2014, 20, 149–166. [Google Scholar]

- Nasri, S.; Heydari Bafghi, R.; Jararh, J. Personality Characteristics, Irrational Beliefs, and Communication Skills as Predictors School Counselors’ Job Performance. Biannu. J. Appl. Couns. 2017, 7, 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassend, O.; Skrondal, A. The NEO Personality Inventory Revised (NEO-PI-R): Exploring the Measurement Structure and Variants of the Five-Factor Model. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 50, 1300–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lievens, F.; Coetsier, P.; De Fruyt, F.; De Maeseneer, J. Medical Students’ Personality Characteristics and Academic Performance: A Five-Factor Model Perspective. Med. Educ. 2002, 36, 1050–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.; Pistole, M.C. Big Five Personality Factors and Facets as Predictors of Openness to Diversity. J. Psychol. 2017, 151, 752–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borges, N.J.; Stratton, T.D.; Wagner, P.J.; Elam, C.L. Emotional Intelligence and Medical Specialty Choice: Findings from Three Empirical Studies. Med. Educ. 2009, 43, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hojat, M.; Zuckerman, M. Personality and Specialty Interest in Medical Students. Med. Teach. 2008, 30, 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, E.M.; Holmboe, E.S. The Relationship between Specialty Choice and Gender of U.S. Medical Students, 1990–2003. Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 2005, 80, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreevy, J.; Wiebe, D. A Preliminary Measurement of the Surgical Personality. Am. J. Surg. 2002, 184, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, B.M.; Coons, M.J.; Kuo, P.C. Personality Differences between Surgery Residents, Nonsurgery Residents, and Medical Students. Surgery 2010, 148, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preece, R.A.; Cope, A.C. Are Surgeons Born or Made? A Comparison of Personality Traits and Learning Styles Between Surgical Trainees and Medical Students. J. Surg. Educ. 2016, 73, 768–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, K.N.; Neidert, G.P.M.; Brubaker-Rimmer, R.; Artalejo, D.; Caruso, D.M. A Psychological Profile of Surgeons and Surgical Residents. J. Surg. Educ. 2010, 67, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, T.; Shinozaki, H.; Makino, T.; Ogawara, H.; Asakawa, Y.; Iwasaki, K.; Matsuda, T.; Abe, Y.; Tozato, F.; Koizumi, M.; et al. Changes in Attitudes toward Interprofessional Health Care Teams and Education in the First- and Third-Year Undergraduate Students. J. Interprof. Care 2012, 26, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmsson, M.; Ponzer, S.; Dahlgren, L.-O.; Timpka, T.; Faresjö, T. Are Female Students in General and Nursing Students More Ready for Teamwork and Interprofessional Collaboration in Healthcare? BMC Med. Educ. 2011, 11, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alghasham, A.A. Effect of Students’ Learning Styles on Classroom Performance in Problem-Based Learning. Med. Teach. 2012, 34 (Suppl. 1), S14–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, S.; Khan, M.A.; Afzal, S.; Shahzad, S.R.; Hamza, M.; Khan, H.A.; Qamar, F.; Javed, M.; Ashraf, M.F.; Mubarak, F.; et al. Association between Academic Learning Strategies and Annual Examination Results among Medical Students of King Edward Medical University. Ann. King Edw. Med. Univ. 2016, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Avrech Bar, M.; Katz Leurer, M.; Warshawski, S.; Itzhaki, M. The Role of Personal Resilience and Personality Traits of Healthcare Students on Their Attitudes towards Interprofessional Collaboration. Nurse Educ. Today 2018, 61, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hojat, M.; Spandorfer, J.; Louis, D.Z.; Gonnella, J.S. Empathic and Sympathetic Orientations toward Patient Care: Conceptualization, Measurement, and Psychometrics. Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 2011, 86, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, K.; Niwa, M.; Fujisaki, K.; Suzuki, Y. Associations between Emotional Intelligence, Empathy and Personality in Japanese Medical Students. BMC Med. Educ. 2018, 18, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Costa, P.; Alves, R.; Neto, I.; Marvão, P.; Portela, M.; Costa, M.J. Associations between Medical Student Empathy and Personality: A Multi-Institutional Study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chew, B.H.; Zain, A.M.; Hassan, F. Emotional Intelligence and Academic Performance in First and Final Year Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Med. Educ. 2013, 13, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aithal, A.P.; Kumar, N.; Gunasegeran, P.; Sundaram, S.M.; Rong, L.Z.; Prabhu, S.P. A Survey-Based Study of Emotional Intelligence as It Relates to Gender and Academic Performance of Medical Students. Educ. Health Abingdon Engl. 2016, 29, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, E.; Costa, P.; Costa, M.J. Empathy of Medical Students and Personality: Evidence from the Five-Factor Model. Med. Teach. 2012, 34, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hojat, M.; Axelrod, D.; Spandorfer, J.; Mangione, S. Enhancing and Sustaining Empathy in Medical Students. Med. Teach. 2013, 35, 996–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertram, K.; Randazzo, J.; Alabi, N.; Levenson, J.; Doucette, J.T.; Barbosa, P. Strong Correlations between Empathy, Emotional Intelligence, and Personality Traits among Podiatric Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Educ. Health Abingdon Engl. 2016, 29, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, F.F.; Nunes, P.; Sa, B.; Williams, S. An Exploration of Changes in Cognitive and Emotional Empathy among Medical Students in the Caribbean. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2014, 5, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- San-Martín, M.; Roig-Carrera, H.; Villalonga-Vadell, R.M.; Benito-Sevillano, C.; Torres-Salinas, M.; Claret-Teruel, G.; Robles, B.; Sans-Boix, A.; Alcorta-Garza, A.; Vivanco, L. Empathy, inter-professional collaboration, and lifelong medical learning in Spanish and Latin-American physicians-in-training who start their postgraduate training in hospitals in Spain. Preliminary outcomes. Aten. Primaria 2017, 49, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dávila-Pontón, Y.; Reyes-Reyes, A.; Calzadilla-Núñez, A.; Utsman, R.; Torres-Martínez, P.; Díaz-Narváez, V. Empathy and Personality Styles in Medical Students. Rev. Colomb. Psicol. 2020, 29, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratelle, C.F.; Guay, F.; Vallerand, R.J.; Larose, S.; Senecal, C. Autonomous, Controlled, and Amotivated Types of Academic Motivation: A Person-Oriented Analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 2007, 99, 734–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doménech-Betoret, F.; Abellán-Roselló, L.; Gómez-Artiga, A. Self-Efficacy, Satisfaction, and Academic Achievement: The Mediator Role of Students’ Expectancy-Value Beliefs. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, A.R.; Young, R.A.; Baumer, J.G. Emotional Intelligence and the ACGME Competencies. J. Grad. Med. Educ. 2010, 2, 508–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gough, H.G.; Bradley, P.; McDonald, J.S. Performance of Residents in Anesthesiology as Related to Measures of Personality and Interests. Psychol. Rep. 1991, 68, 979–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LePine, J.A.; Colquitt, J.A.; Erez, A. Adaptability to Changing Task Contexts: Effects of General Cognitive Ability, Conscientiousness, and Openness to Experience. Pers. Psychol. 2000, 53, 563–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shankar, P.; Dubey, A.; Balasubramanium, R.; Dwivedi, N. Student Attitude towards Communication Skills Learning in a Caribbean Medical School. Australas. Med. J. 2013, 6, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarilakeh, M.; Fargah, F.; Razjouyan, K.; Rahimzadeh, M. Predicating Attitude Toward Learning Communication Skills in Medical Students of Shahid Beheshti University. Dis. Diagn. 2020, 9, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheirati, E.; Shabanifar, A.; Akhlaghi, M.; Peyman, N. Relationship Between Communication Skills and Mental Health Among the Students of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran. J. Sch. Public Health Inst. Public Health Res. 2016, 14, 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Nami, K.; Ghalavandi, H.; Hosseinpoor, A.R. The Role of Students Personality Traits on Students Learning Style in University of Medical Sciences. Dev. Strateg. Med. Educ. 2014, 1, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Molinuevo, B.; Torrubia, R. Does Personality Predict Medical Students’ Attitudes to Learning Communication Skills? Int. J. Med. Educ. 2013, 4, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare-Alamshiri, M.; Saber, S. Prediction of Communication Skills Based on Psycho-Social Class Atmosphere and Social Anxiety of High School Students. Community Health 2017, 4, 127–136. [Google Scholar]

- O’Tuathaigh, C.M.P.; Nadhirah Idris, A.; Duggan, E.; Costa, P.; Costa, M.J. Medical Students’ Empathy and Attitudes towards Professionalism: Relationship with Personality, Specialty Preference and Medical Programme. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0215675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, C.M. Do the Big-Five Personality Traits Predict Empathic Listening and Assertive Communication? Int. J. Listening 2017, 31, 163–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuntze, J.; van der Molen, H.T.; Born, M.P. Big Five Personality Traits and Assertiveness Do Not Affect Mastery of Communication Skills. Health Prof. Educ. 2016, 2, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Franco, C.A.G.d.S.; Franco, R.S.; Cecilio-Fernandes, D.; Severo, M.; Ferreira, M.A. The Assessment of Personality Traits and Its Association with Learning Communication Skills. Sci. Med. Porto Alegre Online 2020, 30, 37326. [Google Scholar]

- Vermetten, Y.J.; Lodewijks, H.G.; Vermunt, J.D. The Role of Personality Traits and Goal Orientations in Strategy Use. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 26, 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holen, A.; Manandhar, K.; Pant, D.S.; Karmacharya, B.M.; Olson, L.M.; Koju, R.; Mansur, D.I. Medical Students’ Preferences for Problem-Based Learning in Relation to Culture and Personality: A Multicultural Study. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2015, 6, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsou, K.-I.; Lin, C.-S.; Cho, S.-L.; Powis, D.; Bore, M.; Munro, D.; Sze, D.M.-Y.; Wu, H.-C.; Hsieh, M.-S.; Lin, C.-H. Using Personal Qualities Assessment to Measure the Moral Orientation and Personal Qualities of Medical Students in a Non-Western Culture. Eval. Health Prof. 2013, 36, 174–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, P.T.; McCrae, R.R. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI); Psychological Assessment Resources: Odessa, FL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Saucier, G.; Hampson, S.; Goldberg, L. Cross-language Studies of Lexical Personality Factors. In Advances in Personality Psychology; Hampson, S.E., Ed.; Psychology Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000; Volume 1, pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- John, O.; Pervin, R.; Pervin, L. The Five-Factor Theory of Personality. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research; McCrae, R., Costa, P.J., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; p. 171. [Google Scholar]

- Sava, F. Inventarul de Personalitate DECAS; ArtPress: Timişoara, Romania, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Extraversion and Happiness: The Mediating Role of Social Support and Hope—PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30015375/ (accessed on 29 June 2021).

- Bennett, K.L.; Phillips, J.P. Finding, Recruiting, and Sustaining the Future Primary Care Physician Workforce: A New Theoretical Model of Specialty Choice Process. Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med. Coll. 2010, 85, S81–S88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.H. The Surgical Personality: Fact or Fiction. Am. J. Surg. 1997, 174, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwarenstein, M.; Goldman, J.; Reeves, S. Interprofessional Collaboration: Effects of Practice-Based Interventions on Professional Practice and Healthcare Outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009, CD000072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoller, J.K.; Taylor, C.A.; Farver, C.F. Emotional Intelligence Competencies Provide a Developmental Curriculum for Medical Training. Med. Teach. 2013, 35, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrides, K. Technical Manual for the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaires (TEIQue), 1st ed.; 2nd Printing; London Psychometric Laboratory: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cherry, M.G.; Fletcher, I.; O’Sullivan, H.; Shaw, N. What Impact Do Structured Educational Sessions to Increase Emotional Intelligence Have on Medical Students? BEME Guide No. 17. Med. Teach. 2012, 34, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.R. Emotional Intelligence as a Crucial Component to Medical Education. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2015, 6, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zaki, J. Empathy: A Motivated Account. Psychol. Bull. 2014, 140, 1608–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goleman, D. Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More than IQ; Bantam Books: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- ECFMG-ACGME Webinar: ACGME Core Competencies and Milestones. Available online: https://www.ecfmg.org/echo/webinars-acgme-core-competencies-2018.html (accessed on 22 September 2021).

- Arora, S.; Ashrafian, H.; Davis, R.; Athanasiou, T.; Darzi, A.; Sevdalis, N. Emotional Intelligence in Medicine: A Systematic Review through the Context of the ACGME Competencies. Med. Educ. 2010, 44, 749–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrick, M.R.; Mount, M.K. The Big Five Personality Dimensions and Job Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Pers. Psychol. 1991, 44, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, G.; Anderson, N. Personality as a Predictor of Working-Related Behavior and Performance: Recent Advances and Directions for Future Research. In International Review of Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Hodgkinson, G., Ford, J., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2008; pp. 261–305. [Google Scholar]

- The AAMC Project on the Clinical Education of Medical Students—MOAM.INFO. Available online: https://moam.info/the-aamc-project-on-the-clinical-education-of-medical-students_59fa642f1723dd0b1e9cf133.html (accessed on 25 September 2021).

- Palsson, R.; Kellett, J.; Lindgren, S.; Merino, J.; Semple, C.; Sereni, D.; EFIM/UEMS Working Group on Competencies in Internal Medicine in Europe. Core Competencies of the European Internist: A Discussion Paper. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2007, 18, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author, Year, and Country | Title of the Study | Aim | Study Type | Sample | Median Age or Mean (Years)/Gender (%) | Methods/Scales | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guilera et al., 2019, Spain [1] | Empathy and big five personality model in medical students and its relationship to gender and specialty preference: a cross-sectional study. | To explore the relation-ship between empathy and personality | Prospective cross-sectional study) | 110 medical students | 22/76.4% F |

| Empathy is related to personality |

| Baron-Cohen et al., 2004, United Kingdom [2] | The empathy quotient: an investigation of adults with Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism, and normal sex differences | To test EQ score in high-functioning autism (HFA) and Asperger Syndrome (AS) | Prospective case–control study | 180 high-functioning autism (HFA) and Asperger Syndrome (AS) subjects | 34.2/72.22% M |

| Empathy deficit in AS/HFA |

| Hojat et al., 2015, USA [4] | Eleven years of data on the Jefferson scale of empathy-medical student version (JSE-S): proxy norm data and tentative cutoff scores | To obtain cutoff scores for the JSE S-version | Prospective observational study | 2637 medical students | 23.4 ± 2.4 SD/50.66% F | JSE-S | Usefulness of empathy in decision making |

| Yusoff et al., 2018, Malaysia [5] | Which personality traits have favourable impact on psychological health during stressful condition? | To investigate which personality traits have a favourable impact on the psychological health of medical students during the most stressful period | Prospective cross-sectional study | 174 medical students | 19.27/67.2% F |

|

|

| Kwon et al., 2016, Korea [6] | Specialty Choice Preference of Medical Students According to Personality Traits by Five-Factor Model. | To evaluate personality by NEO-FFI | Prospective cross-sectional study | 110 medical students | 28.9 ± 2.1 SD/ 39% F |

| Personality important in choosing medical specialty |

| McCrae et al., 1989, USA [7] | Reinterpreting the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator from the Perspective of the Five-Factor Model of Personality. | The MBTI indicator was evaluated from the perspectives of Jung’s theory of psychological types and the five-factor model of personality on the NEO-PI | Prospective observational longitudinal study | 468 adults | 62.7 M and 58.9 F/57.05% M |

| To reinterpret the MBTI in terms of the five-factor model |

| Olsson et al., 2020, Sweden [8] | Personality and Learning Styles in Relation to Attitudes towards Interprofessional Education: A Cross-Sectional Study on Undergraduate Medical Students during Their Clinical Courses | To investigate the effect of personality traits and learning styles on medical students’ attitudes towards IPE | Prospective cross-sectional study | 79 medical students | 29/63% F |

| No correlation between personality, learning style and attitude towards IPE |

| Tamannaeifar et al., 2014, Iran [11] | The relationship between personality characteristics, social support and life satisfaction with university students’ academic performance | To investigate the relationship among personality characteristics, social support and life satisfaction with academic performance | Prospective descriptive, correlative survey | 250 humanities’ students | -/- |

| Relationship between neuroticism and conscientiousness with academic performance |

| Nasri et al., 2017, Iran [12] | Personality characteristics, irrational beliefs, and communication skills as predictors school counselors’ job performance. | To predict counsellors’ job performance based on their personality | Prospective clustering random sampling method | 283 counsellors working | -/- |

| Personality characteristics are predictors of counsellors’ job performance |

| Vassend et al., 2011, USA [13] | The NEO personality inventory revised (NEO-PI-R): Exploring the measurement structure and variants of the five-factor model | To evaluate NEO-PI-R personality | Prospective study | 856 adults | 50.8/55.84% F | NEO-PI-R | NEO-PI-R reflects personality |

| Lievens et al., 2002, Belgium [14] | Medical students’ personality characteristics and academic performance: a five-factor model perspective | To evaluate NEO-PI-R personality | Prospective cross-sectional inventory study and prospective longitudinal study of one cohort of medical students | 785 Flemish medical students and 1361 students from Ghent University | 18.2/60% F | NEO-PI-R | Personality assessment—a useful tool in student counselling and guidance |

| Han et a., 2017, USA [15] | Big five personality factors and facets as predictors of openness to diversity | To examine the associations between NEO-FFI higher order factors and lower order factors and universal-diverse orientation | Prospective cross-sectional study | Study 1—388 medical students and Study 2—176 undergraduates | 21.18/58.6% F—study 1 21.01/72.2% F—study 2 |

| Practical implications on how personality factors are incorporated into current diversity interventions |

| Borges et al., 2008, USA [16] | Emotional intelligence and medical specialty choice: findings from three empirical studies | To examine emotional intelligence (EI) and specialty choice among students at three US medical schools | Prospective observational study | 84 medical students—study 1 250 medical students—study 2 292 medical students—study 3 | 24.3/50% F—study 1 22.7/44.8% F—study 2 23.6/38% F—study 2 |

| No significant differences in EI between students entering primary care and non-primary care specialties |

| Hojat et al., 2008, USA [17] | Personality and specialty interest in medical students | To evaluate the impact of personality score on career interests | Prospective observational study | 1076 medical students | -/64% M | ZKPQ-S | Personalities of medical students predict their career interests |

| Lambert et al., 2005, USA [18] | The relationship between specialty choice and gender of U.S. Medical Students, 1990–2003 | To assess the relationship between specialty choice and gender | Prospective observational study on 14 years | 184262 medical school graduates | -/34.6% F | AAMC GQ | Women were not more responsible than men for from uncontrollable lifestyle specialties |

| McGreevy et al., 2002, USA [19] | Preliminary measurement of the surgical personality. | To test for a distinct surgical personality | Prospective observational study | 39 surgical residents | /61.53% M | NEO-PI-R | Similarity of trait variance from the general population in both male and female surgical residents |

| Hoffman et al., 2010, United Kingdom [20] | Personality differences between surgery residents, nonsurgery residents, and medical students | To examine specialty group differences in personality traits | Prospective observational study | 274 surgical residents and 207 medical students | /53% M | OCEAN personality | Greater levels of conscientiousness were observed in surgery residents |

| Preece et al., 2016, United Kingdom [21] | Are surgeons born or made? A comparison of personality traits and learning styles between surgical trainees and medical students | To score 5 personality domains (extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, openness to experience, and neuroticism) | Prospective cross-sectional study | 53 medical students and 37 surgical trainees | -/- | FFM | Similarities in the personality traits and learning styles of surgical trainees and students interested in surgical career |

| Foster et al., 2010, USA [22] | A psychological profile of surgeons and surgical residents | To determine work-related personality and interest variables | Prospective observational study | 63 surgical residents and 27 attending/teaching surgeons |

|

| WOWI Online assessment tool provides a stable profile of successful surgeons |

| Hayashi et al., 2012, Japan [23] | Changes in attitudes toward interprofessional health care teams and education in the first- and third-year undergraduate students | To assess the implementation of a lecture style for 1st year students and a training style for 3rd year students | Prospective observational study | 285 medical students | -/- |

| Scores improved after the training-style learning approach was implemented in the third-year students |

| Wilhelmsson et al., 2011, Sweden [24] | Are female students in general and nursing students more ready for teamwork and interprofessional collaboration in healthcare? | To investigate if student characteristics have an impact on their open-mindedness about cooperation with other professionals | Prospective cross-sectional study | 670 medical students | -/73.1% F | RIPLS | Indicates some directions for more successful interprofessional education |

| Alghasham et al., 2021, Saudi Arabia [25] | Effect of students’ learning styles on classroom performance in problem-based learning | To identify learning styles | Prospective observational study | 65 medical students | -/73.84% M | Learning Style Inventory Questionnaire | Students should be informed about their preferred learning style |

| Tariq et al., 2016, Pakistan [26] | Association between academic learning strategies and annual examination results among medical students of King Edward Medical University | To find an association between academic learning strategies and annual examination | Prospective simple random sampling | 300 medical students | -/56% F |

| Females outperform their male counterparts in academic performance |

| Avrech Bar et al., 2018, Israel [27] | The role of personal resilience and personality traits of healthcare students on their attitudes towards interprofessional collaboration. | To examine the attitudes of nursing, occupational therapy and physical therapy students towards interprofessional collaboration | Prospective descriptive cross-sectional study | 184 healthcare students | 25.4 ± 2.8/16.8% M |

| IPE, including PBL, should be integrated in health profession students’ training |

| Hojat et al., 2011, USA [28] | Empathic and sympathetic orientations toward patient care: conceptualization, measurement, and psychometrics. | To develop instruments for measuring empathic and sympathetic orientations in patient care and to provide evidence in support of their psychometrics | Prospective observational study | 201 medical students | -/- |

| The validated measures of empathic and sympathetic orientation provide research opportunities |

| Abe et al., 2018, Japan [29] | Associations between emotional intelligence, empathy and personality in Japanese Medical Students. | To investigate: (1) The association between empathy, EI, and personality (2) Gender differences in the association between empathy, EI, and personality | Prospective observational study | 351 medical students | 20.42/70% M |

| Medical students’ EI may be enhanced with thoughtful training |

| Costa et al., 2014, Portugal [30] | Associations between medical student empathy and personality: a multi-institutional study. | To assess associations across institutions, looking for personality differences between students with high empathy and low empathy levels | Prospective observational study | 472 medical students | 21/66.10% F |

| Medical schools may need to pay attention to the personality of medical students |

| Chew et al., 2013, Malaysia [31] | Emotional intelligence and academic performance in first and final year medical students: a cross-sectional study | To examine the effect of EI on academic performance in first- and final-year medical students | Prospective cross-sectional study | 163 medical students | 21.8 ± 1.98/68.7% F | MSCEIT | Emotional skill development may enhance medical students’ academic performance |

| Aithal et al., 2016, India [32] | A survey-based study of emotional intelligence as it relates to gender and academic performance of medical students | To assess trait EI, to examine possible differences in EI level, and to establish a correlation between the EI of medical students and their academic performance | Prospective cross-sectional survey | 200 undergraduate medical students | -/107 F/95 M | TEIQue-SF | Positive correlation between EI and academic performance |

| Magalhães et al., 2012, Portugal [33] | Empathy of medical students and personality: evidence from the five-factor model | To test hypothetical associations between personality dimensions and empathy scores in medical students | Prospective observational study | 350 medical students | -/69.8% F |

| Personality of students should be taken into account in programs to enhance empathy |

| Hojat et al., 2013, USA [34] | Enhancing and sustaining empathy in medical students | To test the hypotheses that medical students’ empathy can be enhanced and sustained by targeted activities | Prospective control-group study | 248 medical students | -/51% F | JSE | Medical students’ empathy can be enhanced and sustained |

| Bertram et al., 2016, USA [35] | Strong correlations between empathy, emotional intelligence, and personality traits among podiatric medical students: a cross-sectional study | To evaluate empathy levels in podiatric medical students in a 4-year doctoral program | Prospective cross-sectional observational study | 150 medical students | -/53.3% F |

| Strong correlation between empathy, EI, and personality in podiatric medical students |

| Youssef et al., 2014, Caribbean [36] | An exploration of changes in cognitive and emotional empathy among medical students in the Caribbean | To explore the empathy profile of students across five years of medical training | Prospective comparative cross-sectional design | 669 medical students | 22–27 years/65% F |

| Medical students’ lower empathy scores appear to be due to a change in the affective component of empathy |

| San-Martín et al., 2016, Spain [37] | Empathy, inter-professional collaboration, and lifelong medical learning in Spanish and Latin-American physicians-in-training who start their postgraduate training in hospitals in Spain. Preliminary outcomes | To identify similarities and differences in empathy, abilities toward interprofessional collaboration, and lifelong medical learning, between Spanish and Latin-American physicians | Prospective observational study | 156 physicians-in-training | 24–50 years/63.46% F |

| Positive influence of empathy in the development of interprofessional collaboration abilities |

| Dávila-Pontón et al., 2020, Ecuador [38] | Empathy and personality styles in medical students | To establish the relationship between empathy and personality styles in medical students | Prospective non-experimental, descriptive, cross-sectional study | 278 medical students | 20.88 ± 2.78/59.7% F |

| Female students present an average score of total empathy greater than men |

| Ratelle et al., 2007, Canada [39] | Autonomous, controlled, and amotivated types of academic motivation: a person-oriented analysis. | To investigate students’ profiles regarding autonomous, controlled, and amotivated regulation, and test whether profile groups differed on some academic adjustment outcomes | Prospective control group study | 4498 high school students | 14.97/50.28% M | Academic motivational profiles | Underscores the importance of studying students’ motivation using a person-oriented approach |

| Doménech-Betoret et al., 2017, Spain [40] | Self-Efficacy, satisfaction, and academic achievement: the mediator role of students’ expectancy-value beliefs. | To examine and identify underlying motivational processes through which students’ academic self-efficacy affects student achievement and satisfaction | Prospective observational study | 797 secondary education students | 12–17 years/ 50.7% M |

| Students’ expectancy value beliefs played a mediator role between academic self-efficacy and the achievement/satisfaction relationship |

| Webb et al., 2010, USA [41] | Emotional Intelligence and the ACGME Competencies. | To evaluate the use of EI assessment and training tools in assessing and enhancing interpersonal and communication skills | Prospective control-group study | 21 residents | -/- | ESCI | EI is a necessary skill in today’s health care |

| Gough et al., 1991, USA [42] | Performance of residents in anesthesiology as related to measures of personality and interests | To study personality variables | Prospective observational study | 99 residents in anaesthesiology | -/- |

| Empathic sensing by the anaesthesiologist function positively |

| LePine et al., 2000, USA [43] | Adaptability to changing task contexts: effects of general cognitive ability, conscientiousness, and openness to experience | To examine the extent to which cognitive ability, conscientiousness, and openness to experience predict decision-making performance | Prospective observational study | 73 undergraduates | -/- | BFIDecision making performance | Unexpected low conscientiousness made better decisions |

| Shankar et al., 2013, Caribbean [44] | Student attitude towards communication skills learning in a Caribbean Medical School. | to establish the attitude of students towards to communication skils | Prospective observational study | 73 undergraduate medical students | 20–25 years/47.1% M | CSAS | Students overall had a positive attitude towards communication skills |

| Akbarilakeh et al., 2020, Iran [45] | Predicating attitude toward learning communication skills in medical students of Shahid Beheshti University. | To investigate the attitude toward learning communication skills based on the personality traits of medical students | Prospective correlational study | 234 medical students | -/65% F |

| The dimension of demographic characteristics are effective in improving the communication skills of medical students |

| Gheirati et al., 2016, Iran [46] | Relationship between communication skills and mental health among the students of Mashhad University Of Medical Sciences | To determine associations between communication skills and mental health | Prospective cross-sectional analytical study | 210 medical students | -/- |

| To promote the mental health of the students, it is recommended to conduct psychological assessments of the students |

| Nami et al., 2014, Iran [47] | The Role of students personality traits on students learning style in university of medical sciences | To investigate the relationship between personality traits and Kolb learning style | Prospective observational study (MANOVA test) | 300 medical students | -/- |

| Significant relationships among the components of personality traits and their learning style |

| Molinuevo et al., 2013, Spain [48] | Does personality predict medical students’ attitudes to learning communication skills? | To determine whether personality is related to medical students’ attitudes towards learning communication skills and self-ratings on communication skills | Prospective control-group study | 1031 medical students (divided in 2 groups: 524 1st-year students and 507 2nd-year students) | 18.89 ± 3.21 years—1st-year students/66% F 20.11 ± 3.10 years—2nd-year students/70% F |

| Personality traits are useful for better student career guidance and counselling |

| Zare-Alamshiri et al., 2017, Iran [49] | Prediction of communication skills based on psycho-social class atmosphere and social anxiety of high school students | To predict the psychological atmosphere of social communication skills and social anxiety in high school students | Prospective observational study | 210 high school students | -/- |

| Psychosocial classroom atmosphere can predict communication skills and social anxiety |

| O’Tuathaigh et al., 2019, Ireland [50] | Medical students’ empathy and attitudes towards professionalism: relationship with personality, specialty preference and medical programme | To examine how empathy, personality, and background factors might impact students’ attitudes towards professionalism in medicine | Prospective cross-sectional questionnaire-based study | 241 medical students | 18–22 (46.6%), 23–27 (43.3%), 28–32 (8.8%), 33–37 (0.8%), 38–42 (0.5%)/49.2% F |

| Empathy and personality factors may act as determinants of students’ attitudes |

| Sims et al., 2017, United Kingdom [51] | Do the big-five personality traits predict empathic listening and assertive communication? | To investigate whether the Big Five had predictive influences on communication competences of active-empathic listening (AEL) and assertiveness | Prospective observational study | 245 adults | <25 years 59; 26–35 years: 42; 36–45 years: 50; 46–55 years: 64; >56 years: 28/75.9% F |

| Agreeableness and Openness uniquely predicted AEL Extraversion had the biggest influence on assertiveness |

| Kuntze etl., 2016, Holland [52] | Big five personality traits and assertiveness do not affect mastery of communication skills. | To investigate whether the big-five personality factors and assertiveness predict mastery of communication skills | Prospective observational study | 143 bachelor students of a psychology curriculum | 19/83% F |

| Trainees can become professional communicators, regardless of their scores on these personality factors |

| Franco et al., 2020, Brazilia [53] | The assessment of personality traits and its association with learning communication skills | To investigate the association between personality traits and attitudes toward learning communication skills in undergraduate medical students | Prospective observational study | 204 students | -/- |

| Elation between agreeableness, extraversion and openness to experience with attitudes on communication skills in students |

| Vermetten et al., 2001, The Netherlands [54] | The Role of personality traits and goal orientations in strategy use | To contribute to the development of an integrated theory on individual learning differences | Prospective observational study | 310 students | 21.5/75% F |

| Individual differences in learning consist of and help explain regularities in learning behaviour |

| Holen et al., 2015, Norway [55] | Medical students’ preferences for problem-based learning in relation to culture and personality: a multicultural study | To explore positive and negative preferences towards PBL in relation to personality traits and sociocultural context | Prospective cross-sectional survey | 449 medical students (123 from Nepal, 229 from Norway and 97 from the USA) | 21.4 Nepal/34.9% F 22.1 Norway/55.28% F 24.1 USA/ 46.10% F | PBL | Preferences related to PBL were significantly and independently determined by personality traits and culture |

| Tsou et al., 2013, Taiwan [56] | Using personal qualities assessment to measure the moral orientation and personal qualities of medical students in a non-western culture | To select candidates with appropriate personal qualities for medical school | Prospective observational study | 746 medical students | 20.3 ± 2.2/ 65.8% M |

| Significant relationships were observed between test components and between the NACE and Big 5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Suciu, N.; Meliț, L.E.; Mărginean, C.O. A Holistic Approach of Personality Traits in Medical Students: An Integrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12822. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312822

Suciu N, Meliț LE, Mărginean CO. A Holistic Approach of Personality Traits in Medical Students: An Integrative Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(23):12822. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312822

Chicago/Turabian StyleSuciu, Nicoleta, Lorena Elena Meliț, and Cristina Oana Mărginean. 2021. "A Holistic Approach of Personality Traits in Medical Students: An Integrative Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18, no. 23: 12822. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312822

APA StyleSuciu, N., Meliț, L. E., & Mărginean, C. O. (2021). A Holistic Approach of Personality Traits in Medical Students: An Integrative Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(23), 12822. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312822