The Role of the Context of Physical Activity for Its Association with Affective Well-Being: An Experience Sampling Study in Young Adults

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures and Instruments

2.3.1. Baseline Measures

2.3.2. Domain of Physical Activity

2.3.3. Being Outdoors, Current Environment, and Current Activity

2.3.4. Affective States

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

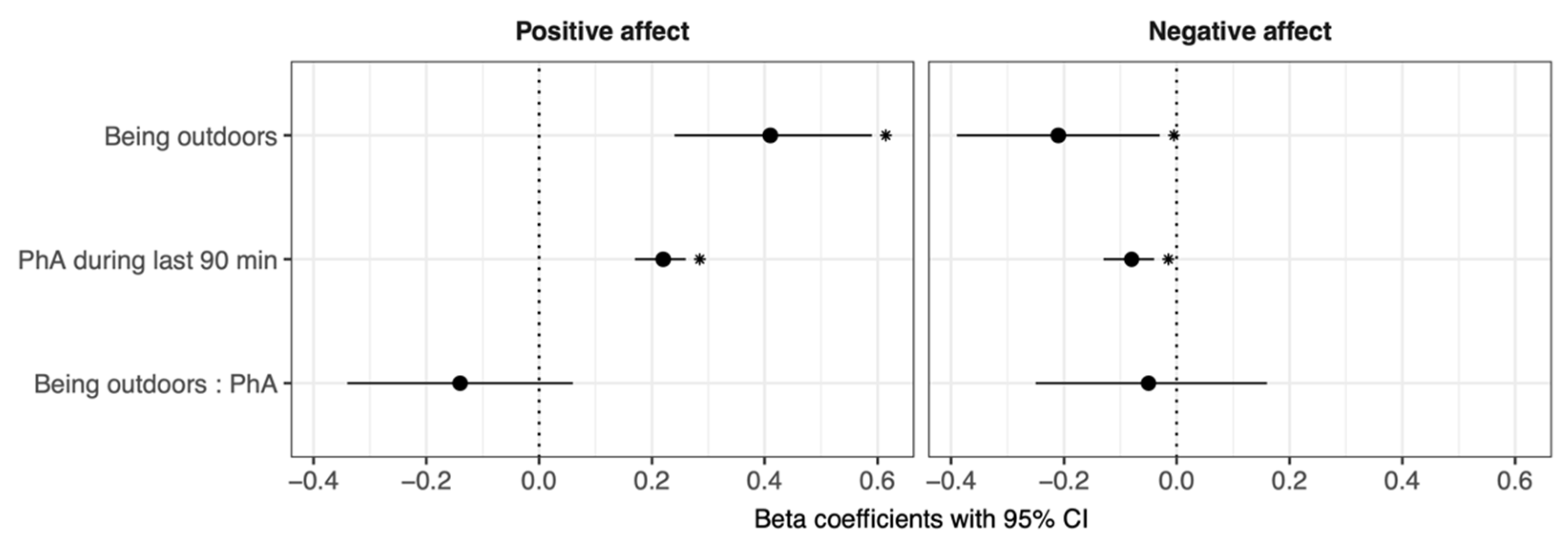

3.2. Association of Physical Activity and Being Outdoors with Affective States

3.2.1. Pairwise Comparisons of Different Outdoor Environments with Affective States

3.2.2. Pairwise Comparisons of Different Domains of Physical Activity with Affective States

3.3. Post-Hoc Analyses of the Associations of Single Affect Items with Being Outdoors and Physical Activity

3.3.1. Pairwise Comparisons of Different Outdoor Environments with Single Affect Items

3.3.2. Pairwise Comparisons of Different Domains of Physical Activity with Single Affect Items

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reiner, M.; Niermann, C.; Jekauc, D.; Woll, A. Long-Term Health Benefits of Physical Activity—A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warburton, D.E.R.; Bredin, S.S.D. Health Benefits of Physical Activity: A Systematic Review of Current Systematic Reviews. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2017, 32, 541–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooney, G.M.; Dwan, K.; Greig, C.A.; Lawlor, D.A.; Rimer, J.; Waugh, F.R.; McMurdo, M.; Mead, G.E. Exercise for Depression. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 9, CD004366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossmann, T.; Kanning, M.; Koudela-Hamila, S.; Hey, S.; Ebner-Priemer, U. The Association between Short Periods of Everyday Life Activities and Affective States: A Replication Study Using Ambulatory Assessment. Front. Psychol. 2013, 4, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carels, R.A.; Coit, C.; Young, K.; Berger, B. Exercise Makes You Feel Good, But Does Feeling Good Make You Exercise?: An Examination of Obese Dieters. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2007, 29, 706–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunton, G.F.; Huh, J.; Leventhal, A.M.; Riggs, N.; Hedeker, D.; Spruijt-Metz, D.; Pentz, M.A. Momentary Assessment of Affect, Physical Feeling States, and Physical Activity in Children. Health Psychol. 2014, 33, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, J.A.; Dunsiger, S.; Williams, D.M. Reciprocal Within-Day Associations between Incidental Affect and Exercise: An EMA Study. Psychol. Health 2018, 33, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauvin, L.; Rejeski, W.J.; Norris, J.L. A Naturalistic Study of the Impact of Acute Physical Activity on Feeling States and Affect in Women. Health Psychol. 1996, 15, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauvin, L.; Rejeski, W.J.; Reboussin, B.A. Contributions of Acute Bouts of Vigorous Physical Activity to Explaining Diurnal Variations in Feeling States in Active, Middle-Aged Women. Health Psychol. 2000, 19, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guérin, E.; Fortier, M.S.; Sweet, S.N. An Experience Sampling Study of Physical Activity and Positive Affect: Investigating the Role of Situational Motivation and Perceived Intensity across Time. Health Psychol. Res. 2013, 1, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollands, L.; Lambert, J.; Price, L.; Powell, D.; Greaves, C. Ecological Momentary Assessment of Mood and Physical Activity in People with Depression. J. Affect Disord. 2020, 271, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanning, M. Using Objective, Real-Time Measures to Investigate the Effect of Actual Physical Activity on Affective States in Everyday Life Differentiating the Contexts of Working and Leisure Time in a Sample with Students. Front. Psychol. 2013, 3, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanning, M.; Ebner-Priemer, U.; Brand, R. Autonomous Regulation Mode Moderates the Effect of Actual Physical Activity on Affective States: An Ambulant Assessment Approach to the Role of Self-Determination. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2012, 34, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lathia, N.; Sandstrom, G.M.; Mascolo, C.; Rentfrow, P.J. Happier People Live More Active Lives: Using Smartphones to Link Happiness and Physical Activity. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0160589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-M.; Konstabel, K.; Mõttus, R.; Lemola, S. Temporal Associations between Objectively Measured Physical Activity and Depressive Symptoms: An Experience Sampling Study. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 920580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, J.P.; Doerksen, S.E.; Elavsky, S.; Hyde, A.L.; Pincus, A.L.; Ram, N.; Conroy, D.E. A Daily Analysis of Physical Activity and Satisfaction with Life in Emerging Adults. Health Psychol. 2013, 32, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöndube, A.; Kanning, M.; Fuchs, R. The Bidirectional Effect between Momentary Affective States and Exercise Duration on a Day Level. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwerdtfeger, A.; Eberhardt, R.; Chmitorz, A.; Schaller, E. Momentary Affect Predicts Bodily Movement in Daily Life: An Ambulatory Monitoring Study. J. Sport Exercise Psychol. 2010, 32, 674–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stavrakakis, N.; Booij, S.H.; Roest, A.M.; de Jonge, P.; Oldehinkel, A.J.; Bos, E.H. Temporal Dynamics of Physical Activity and Affect in Depressed and Nondepressed Individuals. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 1268–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichers, M.; Lothmann, C.; Simons, C.J.P.; Nicolson, N.A.; Peeters, F. The Dynamic Interplay between Negative and Positive Emotions in Daily Life Predicts Response to Treatment in Depression: A Momentary Assessment Study: Emotional Dynamics and Future Treatment Response. Brit. J. Clin. Psychol. 2012, 51, 206–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furley, P. What Modern Sports Competitions Can Tell Us About Human Nature. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 14, 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huppert, F.A. Psychological Well-Being: Evidence Regarding Its Causes and Consequences. Appl. Psychol. Health Wellbeing 2009, 1, 137–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazak Çetinkalp, Z.; Lochbaum, M. Flourishing, Affect, and Relative Autonomy in Adult Exercisers: A Within-Person Basic Psychological Need Fulfillment Perspective. Sports 2018, 6, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapen, J.; Vancampfort, D.; Moriën, Y.; Marchal, Y. Exercise Therapy Improves Both Mental and Physical Health in Patients with Major Depression. Disabil. Rehabil. 2015, 37, 1490–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beute, F.; de Kort, Y.A.W. The Natural Context of Wellbeing: Ecological Momentary Assessment of the Influence of Nature and Daylight on Affect and Stress for Individuals with Depression Levels Varying from None to Clinical. Health Place 2018, 49, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourke, M.; Hilland, T.A.; Craike, M. Contextual Influences on the Within-Person Association between Physical Activity and Affect in Adolescents: An Ecological Momentary Assessment Study. J. Behav. Med. 2021, 44, 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vries, S.; Nieuwenhuizen, W.; Farjon, H.; van Hinsberg, A.; Dirkx, J. In Which Natural Environments Are People Happiest? Large-Scale Experience Sampling in the Netherlands. Landscape Urban Plan. 2021, 205, 103972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, M.C.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Donaire-Gonzalez, D.; Seto, E.; Valentín, A.; Hurst, G.; Carrasco-Turigas, G.; Masterson, D.; Ambròs, A.; Ellis, N.; et al. Momentary Mood Response to Natural Outdoor Environments in Four European Cities. Environ. Int. 2020, 134, 105237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stieger, S.; Aichinger, I.; Swami, V. The Impact of Nature Exposure on Body Image and Happiness: An Experience Sampling Study. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2022, 32, 870–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tost, H.; Reichert, M.; Braun, U.; Reinhard, I.; Peters, R.; Lautenbach, S.; Hoell, A.; Schwarz, E.; Ebner-Priemer, U.; Zipf, A.; et al. Neural Correlates of Individual Differences in Affective Benefit of Real-Life Urban Green Space Exposure. Nat. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 1389–1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunton, G.F.; Liao, Y.; Intille, S.; Huh, J.; Leventhal, A. Momentary Assessment of Contextual Influences on Affective Response during Physical Activity. Health Psychol. 2015, 34, 1145–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.H.; Petrunoff, N.A.; Wang, N.X.; van Dam, R.M.; Sia, A.; Tan, C.S.; Müller-Riemenschneider, F. Daily Park Use, Physical Activity, and Psychological Stress: A Study Using Smartphone-Based Ecological Momentary Assessment amongst a Multi-Ethnic Asian Cohort. Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2022, 22, 100440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellert, S.R.; Wilson, E.O. (Eds.) The Biophilia Hypothesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- White, R.L.; Babic, M.J.; Parker, P.D.; Lubans, D.R.; Astell-Burt, T.; Lonsdale, C. Domain-Specific Physical Activity and Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 52, 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.L.; Bennie, J.; Abbott, G.; Teychenne, M. Work-Related Physical Activity and Psychological Distress among Women in Different Occupations: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A.J.; Medaglia, J.D.; Jeronimus, B.F. Lack of Group-to-Individual Generalizability Is a Threat to Human Subjects Research. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E6106–E6115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, E.I.; Nesse, R.M. Depression Is Not a Consistent Syndrome: An Investigation of Unique Symptom Patterns in the STAR*D Study. J. Affect Disord. 2015, 172, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fried, E.I.; Nesse, R.M. Depression Sum-Scores Don’t Add up: Why Analyzing Specific Depression Symptoms Is Essential. BMC Med. 2015, 13, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mõttus, R.; Kandler, C.; Bleidorn, W.; Riemann, R.; McCrae, R.R. Personality Traits below Facets: The Consensual Validity, Longitudinal Stability, Heritability, and Utility of Personality Nuances. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 112, 474–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mõttus, R.; Sinick, J.; Terracciano, A.; Hřebíčková, M.; Kandler, C.; Ando, J.; Mortensen, E.L.; Colodro-Conde, L.; Jang, K.L. Personality Characteristics below Facets: A Replication and Meta-Analysis of Cross-Rater Agreement, Rank-Order Stability, Heritability, and Utility of Personality Nuances. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2019, 117, e35–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachenberger, J.; Li, Y.-M.; Lemola, S. Physical Activity, Sleep, and Affective Well-Being on the Following Day: An Experience Sampling Study. J. Sleep Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; et al. International Physical Activity Questionnaire: 12-Country Reliability and Validity. Med. Sci. Sport Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a Brief Depression Severity Measure. J. Gen. Intern Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löwe, B.; Spitzer, R.L.; Zipfel, S.; Herzog, W. Gesundheitsfragebogen Für Patienten (PHQ-D); Pfizer: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Das-Friebel, A.; Lenneis, A.; Realo, A.; Sanborn, A.; Tang, N.K.Y.; Wolke, D.; Mühlenen, A.; Lemola, S. Bedtime Social Media Use, Sleep, and Affective Wellbeing in Young Adults: An Experience Sampling Study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2020, 61, 1138–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and Validation of Brief Measures of Positive and Negative Affect: The PANAS Scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A. A Circumplex Model of Affect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 1161–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using Lme4. J. Stat. Soft 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevalence of Self-Reported Physically Active Adults-United States, 2007. MMWR. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2008, 57, 1297–1300. [Google Scholar]

- Grinde, B.; Patil, G. Biophilia: Does Visual Contact with Nature Impact on Health and Well-Being? Int. J. Environ. Public Health 2009, 6, 2332–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Alper, C.M.; Doyle, W.J.; Treanor, J.J.; Turner, R.B. Positive Emotional Style Predicts Resistance to Illness After Experimental Exposure to Rhinovirus or Influenza A Virus. Psychosom. Med. 2006, 68, 809–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredrickson, B.L. The Role of Positive Emotions in Positive Psychology: The Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001, 56, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulrich, R.S. Biophilia, Biophobia, and Natural Landscapes. In The Biophilia Hypothesis; Kellert, S.R., Wilson, E.O., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

| M | SD | Observed Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive affect | 287.9 | 90.1 | 0.0–500.0 |

| Attentive | 55.6 | 22.7 | 0.0–100.0 |

| Content | 63.8 | 22.2 | 0.0–100.0 |

| Enthusiastic | 47.0 | 24.9 | 0.0–100.0 |

| Happy | 63.7 | 22.1 | 0.0–100.0 |

| Relaxed | 58.0 | 23.5 | 0.0–100.0 |

| Negative affect | 102.5 | 83.9 | 0.0–478.0 |

| Annoyed | 23.2 | 25.7 | 0.0–100.0 |

| Bored | 21.0 | 22.0 | 0.0–100.0 |

| Sad | 17.9 | 22.0 | 0.0–100.0 |

| Upset | 14.8 | 20.4 | 0.0–100.0 |

| Worried | 25.6 | 25.4 | 0.0–100.0 |

| Outcome | Contrast | β | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive affect | Indoors–city area | −0.11 | 0.07 | −1.61 | 0.149 |

| Indoors–green space | −0.55 | 0.05 | −10.32 | <0.001 | |

| Indoors–blue space | −0.54 | 0.15 | −3.61 | <0.01 | |

| City area–green space | −0.44 | 0.09 | −5.14 | <0.001 | |

| City area–blue space | −0.43 | 0.16 | −2.62 | <0.05 | |

| Green–blue space | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.985 | |

| Negative affect | Indoors–city area | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.90 | 0.422 |

| Indoors–green space | 0.40 | 0.05 | 7.41 | <0.001 | |

| Indoors–blue space | 0.40 | 0.15 | 2.59 | <0.05 | |

| City area–green space | 0.34 | 0.09 | 3.90 | <0.001 | |

| City area–blue space | 0.33 | 0.17 | 1.99 | 0.072 | |

| Green–blue space | −0.01 | 0.16 | −0.04 | 0.985 |

| Outcome | Contrast | β | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive affect | No PhA–Work | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.18 | 0.893 |

| No PhA–Chores | −0.24 | 0.03 | −7.99 | <0.001 | |

| No PhA–Sports | −0.42 | 0.04 | −9.79 | <0.001 | |

| No PhA–Leisure | −0.36 | 0.03 | −12.44 | <0.001 | |

| No PhA–Other | −0.21 | 0.04 | −5.17 | <0.001 | |

| Work–Chores | −0.25 | 0.06 | −4.09 | <0.001 | |

| Work–Sports | −0.43 | 0.07 | −6.28 | <0.001 | |

| Work–Leisure | −0.37 | 0.06 | −6.04 | <0.001 | |

| Work–Other | −0.22 | 0.07 | −3.32 | <0.01 | |

| Chores–Sports | −0.18 | 0.05 | −3.58 | <0.01 | |

| Chores–Leisure | −0.11 | 0.04 | −2.97 | <0.01 | |

| Chores–Other | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.55 | 0.652 | |

| Sports–Leisure | 0.06 | 0.05 | 1.31 | 0.240 | |

| Sports–Other | 0.21 | 0.06 | 3.57 | <0.01 | |

| Leisure–Other | 0.14 | 0.05 | 2.95 | <0.01 | |

| Negative affect | No PhA–Work | −0.08 | 0.06 | −1.34 | 0.232 |

| No PhA–Chores | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.991 | |

| No PhA–Sports | 0.24 | 0.04 | 5.49 | <0.001 | |

| No PhA–Leisure | 0.18 | 0.03 | 6.05 | <0.001 | |

| No PhA–Other | 0.06 | 0.04 | 1.41 | 0.215 | |

| Work–Chores | 0.08 | 0.06 | 1.22 | 0.270 | |

| Work–Sports | 0.31 | 0.07 | 4.52 | <0.001 | |

| Work–Leisure | 0.25 | 0.06 | 4.09 | <0.001 | |

| Work–Other | 0.13 | 0.07 | 1.97 | 0.074 | |

| Chores–Sports | 0.24 | 0.05 | 4.69 | <0.001 | |

| Chores–Leisure | 0.17 | 0.04 | 4.48 | <0.001 | |

| Chores–Other | 0.06 | 0.05 | 1.19 | 0.279 | |

| Sports–Leisure | −0.06 | 0.05 | −1.27 | 0.254 | |

| Sports–Other | −0.18 | 0.06 | −3.07 | <0.01 | |

| Leisure–Other | −0.12 | 0.05 | −2.39 | <0.05 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.-M.; Hachenberger, J.; Lemola, S. The Role of the Context of Physical Activity for Its Association with Affective Well-Being: An Experience Sampling Study in Young Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10468. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710468

Li Y-M, Hachenberger J, Lemola S. The Role of the Context of Physical Activity for Its Association with Affective Well-Being: An Experience Sampling Study in Young Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(17):10468. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710468

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yu-Mei, Justin Hachenberger, and Sakari Lemola. 2022. "The Role of the Context of Physical Activity for Its Association with Affective Well-Being: An Experience Sampling Study in Young Adults" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, no. 17: 10468. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710468

APA StyleLi, Y.-M., Hachenberger, J., & Lemola, S. (2022). The Role of the Context of Physical Activity for Its Association with Affective Well-Being: An Experience Sampling Study in Young Adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10468. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191710468