What We Ask about When We Ask about Quarantine? Content and Sentiment Analysis on Online Help-Seeking Posts during COVID-19 on a Q&A Platform in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection and Pre-Processing

3.2. Data Analysis

3.2.1. Time Series Analysis

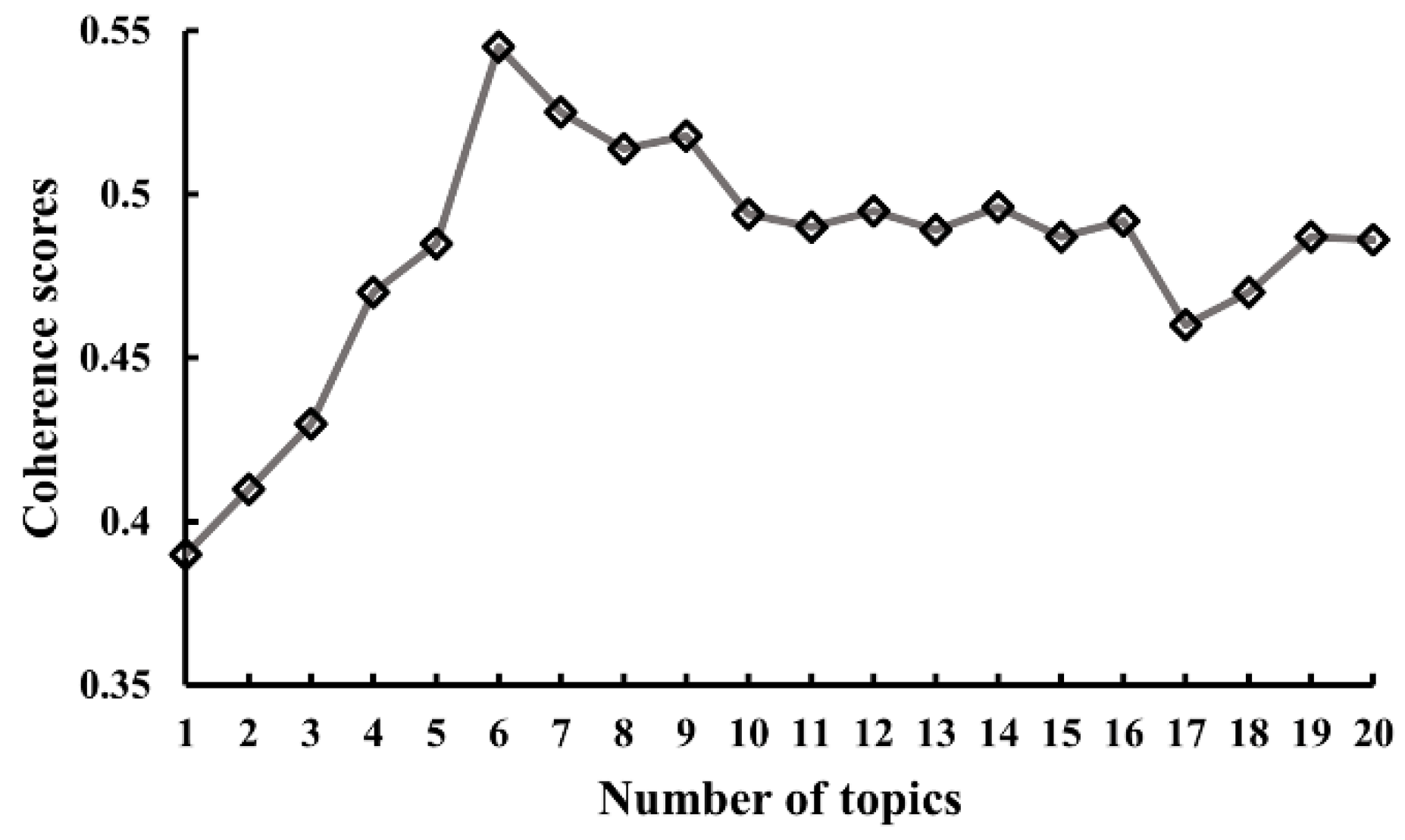

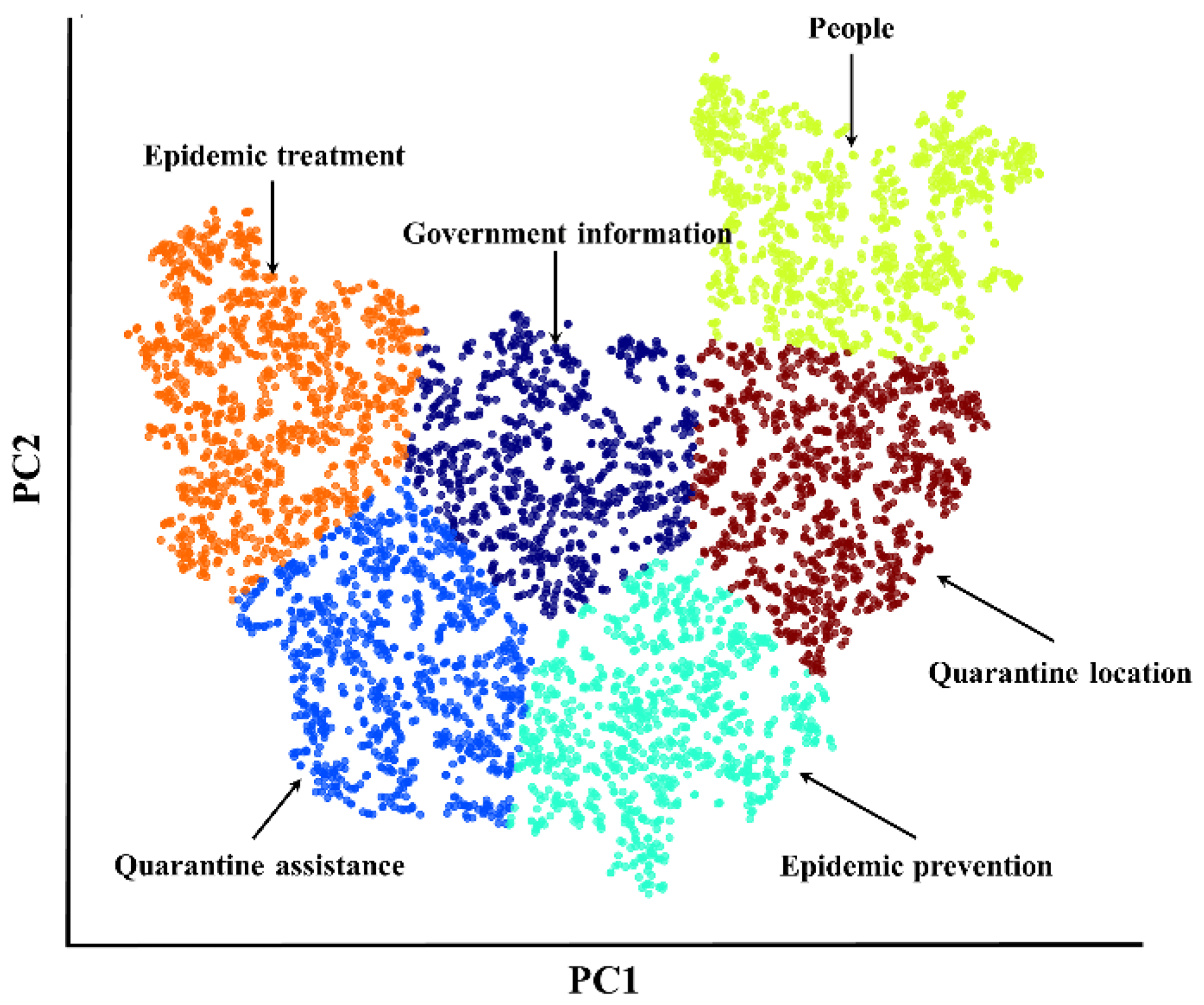

3.2.2. Topic Extraction and Classification Analysis

3.2.3. Sentiment Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Post Description

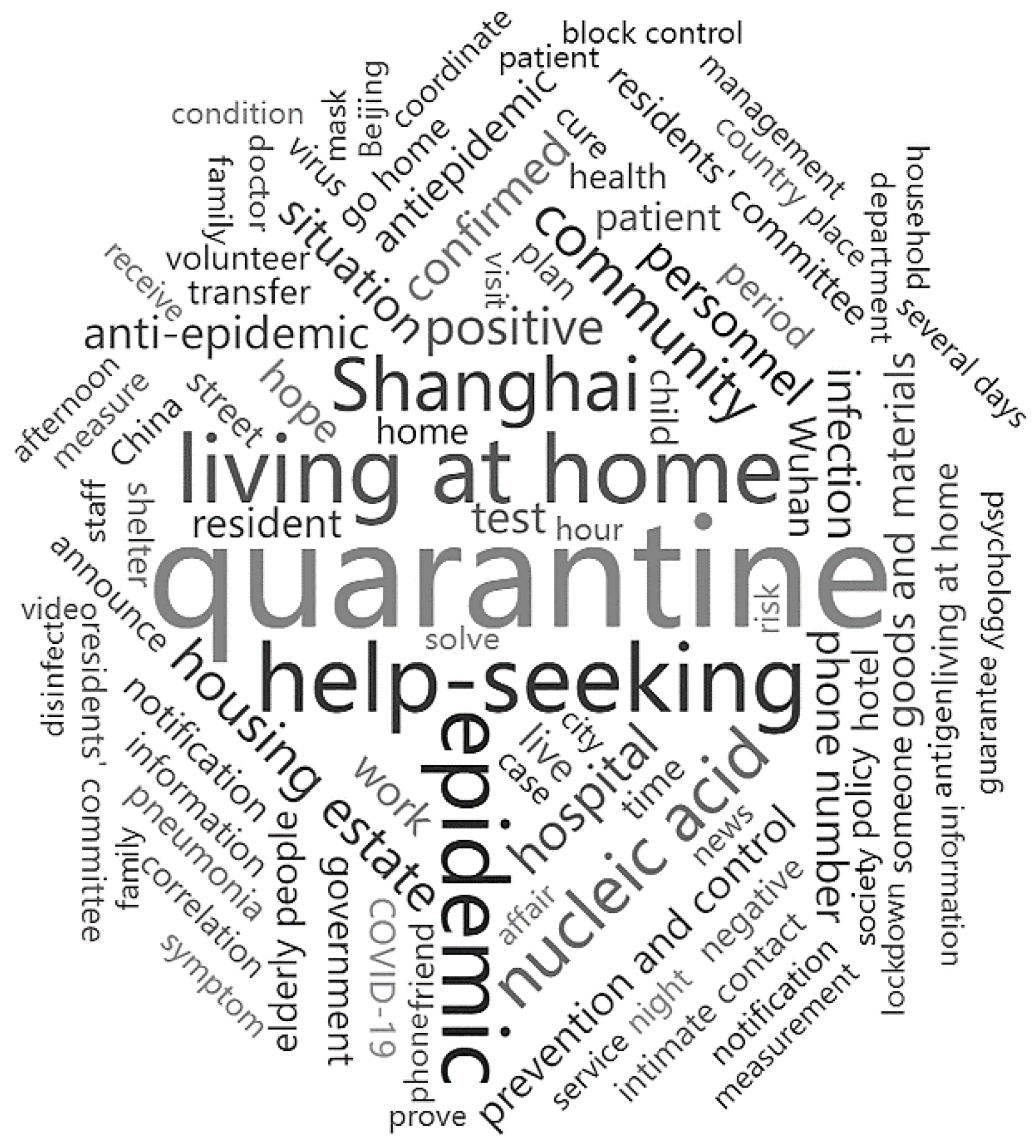

4.2. Topic Modelling

4.3. Sentiment Tendency Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Time Series Discussion

5.2. Topic Discussion

5.3. Sentiment Tendency Analysis

5.4. Limitation and Future Direction

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | English | Chinese | No. | English | Chinese | No. | English | Chinese |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | quarantine | 隔离 | 18 | work | 工作 | 35 | home | 家里 |

| 2 | help-seeking | 求助 | 19 | prevention and control | 防控 | 36 | plan | 安排 |

| 3 | living at home | 居家 | 20 | hope | 希望 | 37 | COVID-19 | 新冠 |

| 4 | epidemic | 疫情 | 21 | resident | 居民 | 38 | transfer | 转运 |

| 5 | Shanghai | 上海 | 22 | live | 生活 | 39 | health | 健康 |

| 6 | nucleic acid | 核酸 | 23 | goods and materials | 物资 | 40 | go home | 回家 |

| 7 | community | 小区 | 24 | patient | 患者 | 41 | information | 信息 |

| 8 | housing estate | 社区 | 25 | government | 政府 | 42 | pneumonia | 肺炎 |

| 9 | hospital | 医院 | 26 | Wuhan | 武汉 | 43 | shelter | 方舱 |

| 10 | positive | 阳性 | 27 | elderly people | 老人 | 44 | negative | 阴性 |

| 11 | personnel | 人员 | 28 | residents’ committee | 居委 | 45 | policy | 政策 |

| 12 | situation | 情况 | 29 | notification | 通知 | 46 | announce | 发布 |

| 13 | confirmed | 确诊 | 30 | period | 期间 | 47 | intimate contact | 密接 |

| 14 | anti-epidemic | 抗疫 | 31 | time | 时间 | 48 | China | 中国 |

| 15 | test | 检测 | 32 | hotel | 酒店 | 49 | solve | 解决 |

| 16 | phone number | 电话 | 33 | child | 孩子 | 50 | psychology | 心理 |

| 17 | infection | 感染 | 34 | street | 街道 |

| Label | English | Chinese | Label | English | Chinese |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | phone number | 电话 | 4 | positive | 阳性 |

| information | 消息 | confirmed | 确诊 | ||

| notification | 通知 | quarantine | 隔离 | ||

| service | 服务 | transfer | 转运 | ||

| goods and materials | 物资 | cure | 治疗 | ||

| live | 生活 | antigen | 抗原 | ||

| visit | 上门 | intimate contact | 密接 | ||

| psychology | 心理 | solve | 解决 | ||

| emotion | 情绪 | coordinate | 配合 | ||

| help-seeking | 求助 | infection | 感染 | ||

| 2 | living at home | 居家 | 5 | epidemic | 疫情 |

| company | 公司 | nucleic acid | 核酸 | ||

| housing estate | 社区 | mask | 口罩 | ||

| hospital | 医院 | measurement | 措施 | ||

| hotel | 酒店 | lockdown | 封城 | ||

| shelter | 方舱 | block control | 封控 | ||

| living at home | 在家 | protection | 防护 | ||

| home | 家里 | inspect | 检查 | ||

| workplace | 单位 | risk | 风险 | ||

| school | 学校 | disinfect | 消毒 | ||

| 3 | patient | 患者 | 6 | China | 中国 |

| elderly people | 老人 | anti-epidemic | 抗疫 | ||

| child | 孩子 | hope | 希望 | ||

| friend | 朋友 | government | 政府 | ||

| family | 家人 | residents’ committee | 居委 | ||

| volunteer | 志愿者 | announce | 发布 | ||

| mother | 母亲 | news | 新闻 | ||

| in person | 本人 | management | 管理 | ||

| medical personnel | 医护人员 | report | 报告 | ||

| doctor | 医生 | center for disease control and prevention | 疾控中心 |

| No. | English | Chinese |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Depressed | 抑郁的 |

| 2 | Worried | 担心的 |

| 3 | Repressive | 压抑的 |

| 4 | Severe | 严峻的 |

| 5 | Anxious | 焦虑的 |

| 6 | Corrupted | 崩溃的 |

| 7 | Fighting | 努力的 |

| 8 | Healthy | 健康的 |

| 9 | Angry | 气愤的 |

| 10 | Helpless | 无奈的 |

References

- Åslund, A. Responses to the COVID-19 crisis in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2020, 61, 532–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X. Pandemic and lockdown: A territorial approach to COVID-19 in China, Italy and the United States. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2020, 61, 423–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Tong, C.; Zhang, A.; Wang, B.; Shi, Z.; Yao, Y.; Jia, P. An extended Weight Kernel Density Estimation model forecasts COVID-19 onset risk and identifies spatiotemporal variations of lockdown effects in China. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, A.; Sandalwala, J.; Joshi, M.; Gupta, A.K. COVID-19: Government intervention and post COVID complications in India. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. Sustainable COVID-19 mitigation: Wuhan lockdowns, health inequities, and patient evacuation. Int. J. Health Policy Manag. 2020, 9, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lull, J. Media, Communication, Culture: A Global Approach; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ruddock, A. Understanding Audiences: Theory and Method; Sage Publications Inc.: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, E.; Blumler, J.; Gurevitch, M. Uses and gratifications research. Public Opin. Q. 1974, 37, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Yu, P. The role of digital devices in chronic disease management during the COVID-19 pandemic—A study of senior citizens in Wuhan. Asian J. Commun. 2021, 31, 373–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Eisenman, D.; Han, Z. Temporal dynamics of public emotions during the COVID-19 pandemic at the epicenter of the outbreak: Sentiment analysis of Weibo posts from Wuhan. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e27078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Adams, P.C.; Wang, J. Shifting moods on Sina Weibo: The first 12 weeks of COVID-19 in Wuhan. New Media Soc. 2021, -0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Li, H.; Li, P.Z. Public response on the Internet in public health emergencies: An example of topics related to COVID-19 on Zhihu Platform. Mod. Intell. 2021, 41, 78–88. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, C.; Li, Y.; Chen, A.; Tang, Y. What triggers online help-seeking retransmission during the COVID-19 period? Empirical evidence from Chinese social media. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0241465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castonguay, J.; Filer, C.R.; Pitts, M.J. Seeking help for depression: Applying the health belief model to illness narratives. South. Commun. J. 2016, 81, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshaabi, T.; Arnold, M.V.; Minot, J.R.; Adams, J.L.; Dewhurst, D.R.; Reagan, A.J.; Muhamad, R.; Danforth, C.M.; Dodds, P.S. How the world’s collective attention is being paid to a pandemic: COVID-19 related n-gram time series for 24 languages on Twitter. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0244476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, L.; Sundin, E. Mobile bystanders and rubbernecks, disaster tourists, and helpers. Towards a theoretical framework for critically studying action possibilities at accident sites. Mob. Media Commun. 2021, 9, 531–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thackeray, R.; Neiger, B.L.; Smith, A.K.; Van Wagenen, S.B. Adoption and use of social media among public health departments. BMC Public Health 2012, 12, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shi, J.; Kim, H.K. Integrating risk perception attitude framework and the theory of planned behavior to predict mental health promotion behaviors among young adults. Health Commun. 2019, 35, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, D.C.; Cedric Harville, I. Peer reviewed: EHealth literacy, online help-seeking behavior, and willingness to participate in mHealth chronic disease research among African Americans, Florida, 2014–2015. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2016, 13, E156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ji, X.W. The Influence of Counseling Context-Related Factors on College Students’ Willingness and Behavior to Seek Help. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing Normal University, Nanjing, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kor, P.P.K.; Leung, A.Y.M.; Parial, L.L.; Wong, E.M.L.; Dadaczynski, K.; Okan, O.; Amoah, P.A.; Wang, S.S.; Deng, R.; Cheung, T.C.C. Are People With Chronic Diseases Satisfied With the Online Health Information Related to COVID-19 During the Pandemic? J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2021, 53, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.Z.; Zeng, F.; Zhang, A.; Tong, C.; Shen, X.; Liu, Z.; Shi, Z. Online public opinion during the first epidemic wave of COVID-19 in China based on Weibo data. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Zheng, X.; Liu, H.; Li, J.; Wang, P. Analysis of spatiotemporal characteristics of big data on social media sentiment with COVID-19 epidemic topics. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2020, 140, 110123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Blei, D.M. Probabilistic topic models. Commun. ACM 2012, 55, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Çallı, L.; Çallı, F. Understanding Airline Passengers during COVID-19 Outbreak to Improve Service Quality: Topic Modeling Approach to Complaints with Latent Dirichlet Allocation Algorithm. Transp. Res. Rec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, T.L.; Steyvers, M. Finding scientific topics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 5228–5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X. Using social media to mine and analyze public opinion related to COVID-19 in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dahal, B.; Kumar, S.A.; Li, Z. Topic modeling and sentiment analysis of global climate change tweets. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2019, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Li, S.; Yang, X.; Qin, C. Use of social media for the detection and analysis of infectious diseases in China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2016, 5, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van der Maaten, L.; Hinton, G. Visualizing Data Using t-SNE. Available online: https://www.jmlr.org/papers/volume9/vandermaaten08a/vandermaaten08a.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2022).

- Lucini, F.R.; Tonetto, L.M.; Fogliatto, F.S.; Anzanello, M.J. Text mining approach to explore dimensions of airline customer satisfaction using online customer reviews. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2020, 83, 101760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCallum, A.K. Mallet: A Machine Learning for Language Toolkit. 2002. Available online: http://mallet.cs.umass.edu (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Petrie, K.; Faasse, K. Monitoring Public Anxiety about Flu Weblog Message. 2009. Available online: https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2009/06/11/keith-j-petrie-and-kate-faasse-monitoring-public-anxiety-about-flu/ (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Michael, F.; Goodchild, J.; Glennon, A. Crowdsourcing geographic information for disaster response: A research frontier. Int. J. Digit. Earth 2010, 3, 231–241. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, A.M.; Bryant, J.; Zillmann, D. Media effects: Advances in theory and research. In Media Effects; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Qiuqing, M.; Huixiang, X.; Zirong, Y. Analysis on Health Information Needs and Evolution of Internet Users in the Post-Epidemic Period. Libr. J. 2022, 41, 119. [Google Scholar]

- Haqqu, R.; Hastjarjo, S.; Slamet, Y. Teenagers’ entertainment satisfaction in watching talk show program through YouTube. J. Messenger 2019, 11, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nouri, S.; Khoong, E.C.; Lyles, C.R.; Karliner, L. Addressing equity in telemedicine for chronic disease management during the COVID-19 pandemic. NEJM Catal. Innov. Care Deliv. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saqib, M.A.N.; Siddiqui, S.; Qasim, M.; Jamil, M.A.; Rafique, I.; Awan, U.A.; Ahmad, H.; Afzal, M.S. Effect of COVID-19 lockdown on patients with chronic diseases. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020, 14, 1621–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | Objective of study | Method | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| [14] Castonguay et al., 2016 | Exploring the help-seeking process | Interviews were used to examine the health belief model | The main barrier preventing help-seeking was fear of the unknown treatment process. |

| [15] Alshaabi et al., 2021 | Enhancing any analysis that may be useful during the pandemic, as well as retrospective surveys. | Multiple languages and n-gram analysis | In all languages, the word ‘virus’ peaked in January 2020, followed by a decline in February, and then a surge in March and April. The world’s collective attention declined as the virus spread out from China. |

| [16] Andersson and Sundin, 2021 | Identification of theoretical perspectives relevant to the analysis of mobile media practices and discussion of the ethical implications of these perspectives. | Theories of people’s behavior at the scene of trauma were combined with discussions about witnessing both in and through the media. | Mobile bystanders must be considered simultaneously as transgressors of social norms and as emphatic witnesses behaving in accordance with the digital media age |

| [13] Luo et al., 2020 | Exploring the driving force behind the retweeting of online help-seeking posts. | An analytical framework that emphasizes content features was used | The importance of individual information completeness, high proximity, instrumental support seeking. |

| [17] Thackeray et al., 2012 | Assessing the most common social media used by state public health departments (SHDs) and the frequency with which social media is used to interact to engage audiences. | Cross sectional study | A total of 86.7% had a Twitter account, 56% a Facebook account, and 43% a YouTube channel. SHDs had very little interaction with audiences. The most common topics for posts and tweets related to staying healthy and diseases. |

| [18] Shi and Kim, 2019 | Examining the factors that lead young Singaporeans to seek advice and adopt a self-help approach. | Risk perception attitude framework and theory of planned behavior were integrated. | The nature of focal behavior and attitudes are boundary conditions of the interaction effect between perceived risk and efficacy. |

| [19] James and Cedric Harville, 2016 | Assessing the relationship between electronic health literacy (EHL) and willingness to participate in mobile health (mHealth) research. | Questionnaire | Significantly higher eHEALS scores among women, smartphone owners, those who use the Internet to seek health information, and those willing to participate in mHealth research. |

| [20] Ji, 2013 | Exploring the help-seeking behavior of university students when experiencing psychological distress. | Questionnaires and structural equation modeling | Students with positive help-seeking intentions, attitudes, and more indirect help-seeking experiences are more likely to engage in help-seeking behavior. |

| [9] Wu and Yu, 2021 | Exploring the willingness of older people in Wuhan to use digital devices for chronic disease management during and after the city lockdown. | Semi-structured interviews | Cultural background, medical knowledge, and socio-economic infrastructure play a key role in influencing the perception and use of remote medical and remote care services by older people. |

| [21] Kor et al., 2021 | Satisfaction with COVID-19-related online information among patients with and without chronic conditions. | Online survey | The majority of PWCD who looked to social media for online information related to COVID-19 had significantly lower levels of information satisfaction than those without chronic health conditions. |

| [22] Shi et al., 2022 | Analyzing the development of online public opinion in terms of fine-grained emotions during the COVID-19 outbreak in China | LDA model and sentiment analysis | A strong emotional impact is observed during holidays. Central cities reacted more strongly to the COVID-19 outbreak than surrounding cities. |

| [23] Zhu et al., 2020 | Exploring social media topics and shifting sentiment features. | LDA model | Discovered the new characteristics of the “double peaks” of public opinion. Popular topics have the characteristic of slowly declining over time. |

| [10] Yu et al., 2021 | Exploring the significant events that influenced emotional changes during the COVID-19 pandemic | Sentiment analysis | Negative emotions were the most salient emotions detected on Weibo during the night. |

| [11] Zheng et al., 2021 | Investigating the evolution of public sentiment in Wuhan, China in the first 12 weeks after the emergence of COVID-19 | Longitude analysis | The study found a progression from confusion/fear to disappointment/frustration, to depression/anxiety, finally to happiness/gratitude. |

| [12] Zhang et al., 2021 | Exploring how to properly monitor We Media and effectively manage its violations | A tripartite evolutionary game model of government, We Media, and public participation was constructed | Government regulation plays an important role in restricting We Media’s information release |

| No. | Term | Frequency | No. | Term | Frequency | No. | Term | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | quarantine | 16,881 | 18 | work | 2704 | 35 | home | 1640 |

| 2 | help-seeking | 10,672 | 19 | prevention and control | 2572 | 36 | plan | 1624 |

| 3 | living at home | 10,536 | 20 | hope | 2548 | 37 | COVID-19 | 1604 |

| 4 | epidemic | 10,128 | 21 | resident | 2496 | 38 | transfer | 1600 |

| 5 | Shanghai | 7556 | 22 | live | 2460 | 39 | health | 1540 |

| 6 | nucleic acid | 6640 | 23 | goods and materials | 2408 | 40 | go home | 1528 |

| 7 | community | 4964 | 24 | patient | 2240 | 41 | information | 1528 |

| 8 | housing estate | 4428 | 25 | government | 1988 | 42 | pneumonia | 1520 |

| 9 | hospital | 4084 | 26 | Wuhan | 1960 | 43 | shelter | 1476 |

| 10 | positive | 3972 | 27 | elderly people | 1896 | 44 | negative | 1456 |

| 11 | personnel | 3468 | 28 | Residents’ committee | 1844 | 45 | policy | 1432 |

| 12 | situation | 3424 | 29 | notification | 1844 | 46 | announce | 1432 |

| 13 | confirmed | 3388 | 30 | period | 1820 | 47 | intimate contact | 1408 |

| 14 | anti-epidemic | 3164 | 31 | time | 1768 | 48 | China | 1364 |

| 15 | test | 3072 | 32 | hotel | 1768 | 49 | solve | 1352 |

| 16 | phone number | 2836 | 33 | child | 1724 | 50 | psychology | 1324 |

| 17 | infection | 2820 | 34 | street | 1704 |

| Topic No. | Label | 10 Representative Words Selected from the Top 30 Most Salient Words |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Quarantine assistance | phone number, information, notification, service, goods and materials, live, visit, psychology, emotion, help-seeking |

| 2 | Quarantine location | living at home, company, housing estate, hospital, hotel, shelter, living at home, home, workplace, school |

| 3 | People | patient, elderly people, child, friend, family, volunteer, mother, in person, medical personnel, doctor |

| 4 | Epidemic treatment | positive, confirmed, quarantine, transfer, cure, antigen, intimate contact, solve, coordinate, infection |

| 5 | Epidemic prevention | epidemic, nucleic acid, mask, measurement, lockdown, block control, protection, inspect, risk, disinfect |

| 6 | Government information | China, anti-epidemic, hope, government, residents’ committee, announce, news, management, report, center for disease control and prevention |

| Topic No. | Keywords | Posts Number | Posts Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | phone number, information, notification, service, goods and materials, live, visit, psychology, emotion, help-seeking | 2671 | 0.25 |

| 2 | living at home, company, housing estate, hospital, hotel, shelter, living at home, home, workplace, school | 2458 | 0.23 |

| 3 | patient, elderly people, child, friend, family, volunteer, mother, in person, medical personnel, doctor | 1710 | 0.16 |

| 4 | positive, confirmed, quarantine, transfer, cure, antigen, intimate contact, solve, coordinate, infection | 1496 | 0.14 |

| 5 | epidemic, nucleic acid, mask, measurement, lockdown, block control, protection, inspect, risk, disinfect | 1389 | 0.13 |

| 6 | China, anti-epidemic, hope, government, residents’ committee, announce, news, management, report, center for disease control and prevention | 962 | 0.09 |

| Mean | Standard Deviation | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | 0.692 | 0.097 | 1573 |

| Neutral | 0.516 | 0.134 | 4473 |

| Negative | 0.112 | 0.188 | 4639 |

| Key Words (Adj) | Emotional Polarity | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Depressed | Negative | 874 |

| Worried | Negative | 786 |

| Repressive | Negative | 655 |

| Severe | Negative | 421 |

| Anxious | Negative | 329 |

| Corrupted | Negative | 194 |

| Fighting | Positive | 161 |

| Healthy | Positive | 86 |

| Angry | Negative | 27 |

| Helpless | Negative | 14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, L.; Hua, L.; Gao, F. What We Ask about When We Ask about Quarantine? Content and Sentiment Analysis on Online Help-Seeking Posts during COVID-19 on a Q&A Platform in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 780. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010780

Li L, Hua L, Gao F. What We Ask about When We Ask about Quarantine? Content and Sentiment Analysis on Online Help-Seeking Posts during COVID-19 on a Q&A Platform in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(1):780. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010780

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Luanying, Lin Hua, and Fei Gao. 2023. "What We Ask about When We Ask about Quarantine? Content and Sentiment Analysis on Online Help-Seeking Posts during COVID-19 on a Q&A Platform in China" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 1: 780. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010780