The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Teachers and Its Possible Risk Factors: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Data Collection and Eligibility Criteria

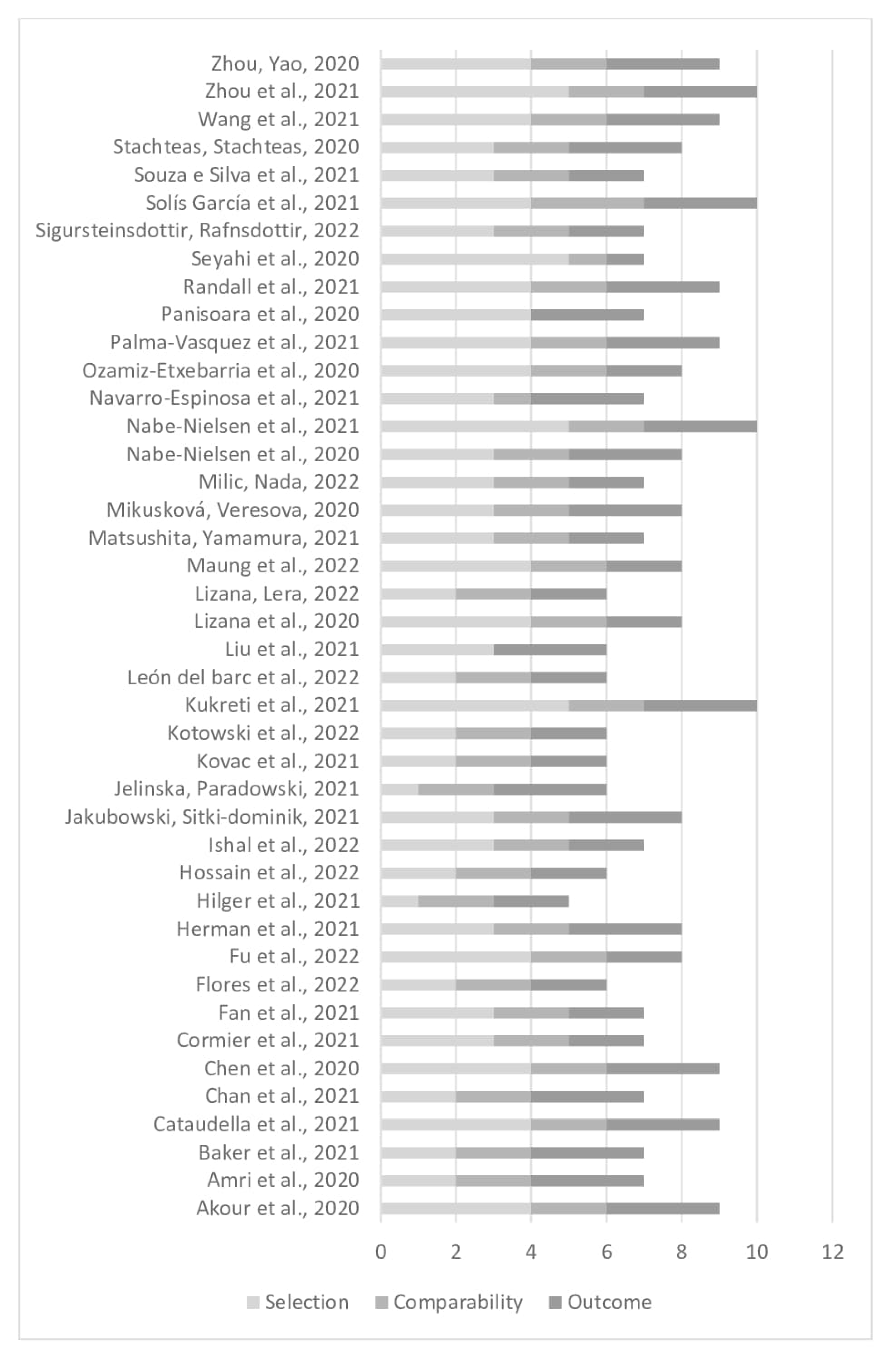

2.3. Assessment of Methodological Quality

2.4. Characteristics of the Studies Included

2.5. Assessment of Methodological Quality

2.6. Ethical Issue

3. Results

3.1. Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Teaching and the COVID-19 Pandemic

3.2. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Teaching and the COVID-19 Pandemic

3.3. Burnout Syndrome, Teaching and the COVID-19 Pandemic

3.4. Depressive Disorder, Teaching and the COVID-19 Pandemic

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baldaçara, L.; Silva, F.; Castro, J.G.D.; Santos, G.D.C.A. Common psychiatric symptoms among public school teachers in Palmas, Tocantins, Brazil. An observational cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med. J. 2015, 133, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Seibt, R.; Spitzer, S.; Druschke, D.; Scheuch, K.; Hinz, A. Predictors of mental health in female teachers. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2013, 26, 856–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braeunig, M.; Pfeifer, R.; Schaarschmidt, U.; Lahmann, C.; Bauer, J. Factors influencing mental health improvements in school teachers. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kidger, J.; Brockman, R.; Tilling, K.; Campbell, R.; Ford, T.; Araya, R.; King, M.; Gunnell, D. Teachers’ wellbeing and depressive symptoms, and associated risk factors: A large cross sectional study in English secondary schools. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 192, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Melguizo-Ibáñez, E.; González-Valero, G.; Ubago-Jiménez, J.L.; Puertas-Molero, P. Resilience, Stress, and Burnout Syndrome According to Study Hours in Spanish Public Education School Teacher Applicants: An Explanatory Model as a Function of Weekly Physical Activity Practice Time. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2021, 398, 1700–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNESCO. COVID-19 E Educação Superior: Dos Efeitos Imediatos AO Dia Seguinte. Análises de Impactos, Respostas Políticas E Recomendações. Organização Das Nações Unidas Para a Educação, a Ciência E a Cultura. 2020. Available online: https://pt.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse (accessed on 9 April 2022).

- Chen, H.; Liu, F.; Pang, L.; Liu, F.; Fang, T.; Wen, Y.; Chen, S.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Are You Tired of Working Amid the Pandemic? The Role of Professional Identity and Job Satisfaction against Job Burnout. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panisoara, I.O.; Lazar, I.; Panisoara, G.; Chirca, R.; Ursu, A.S. Motivation and Continuance Intention towards Online Instruction among Teachers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Mediating Effect of Burnout and Technostress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- e Silva, N.S.S.; Barbosa, R.E.C.; Leão, L.L.; Pena, G.D.G.; de Pinho, L.; de Magalhães, T.A.; Silveira, M.F.; Rossi-Barbosa, L.A.R.; Silva, R.R.V.; Haikal, D.S. Working conditions, lifestyle and mental health of Brazilian public-school teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatriki 2021, 32, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadyaya, K.; Toyama, H.; Salmela-Aro, K. School Principals’ Stress Profiles During COVID-19, Demands, and Resources. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 731929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfefferbaum, B.; North, C.S. Mental Health and the Covid-19 Pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubowski, T.D.; Sitko-Dominik, M.M. Teachers’ mental health during the first two waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilger, K.J.E.; Scheibe, S.; Frenzel, A.C.; Keller, M.M. Exceptional circumstances: Changes in teachers’ work characteristics and well-being during COVID-19 lockdown. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2021, 36, 516–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lizana, P.; Vega-Fernadez, G.; Gomez-Bruton, A.; Leyton, B.; Lera, L. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Teacher Quality of Life: A Longitudinal Study from before and during the Health Crisis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akour, A.; Al-Tammemi, A.B.; Barakat, M.; Kanj, R.; Fakhouri, H.N.; Malkawi, A.; Musleh, G. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Emergency Distance Teaching on the Psychological Status of University Teachers: A Cross-Sectional Study in Jordan. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2020, 103, 2391–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amri, A.; Abidli, Z.; Elhamzaoui, M.; Bouzaboul, M.; Rabea, Z.; Ahami, A.O.T. Assessment of burnout among primary teachers in confinement during the COVID-19 period in Morocco: Case of the Kenitra. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2020, 35 (Suppl. S2), 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, C.N.; Peele, H.; Daniels, M.; Saybe, M.; Whalen, K.; Overstreet, S. Trauma-Informed Schools Learning Collaborative The New Orleans The Experience of COVID-19 and Its Impact on Teachers’ Mental Health, Coping, and Teaching. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 50, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataudella, S.; Carta, S.; Mascia, M.; Masala, C.; Petretto, D.; Agus, M.; Penna, M. Teaching in Times of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Pilot Study on Teachers’ Self-Esteem and Self-Efficacy in an Italian Sample. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, M.-K.; Sharkey, J.D.; Lawrie, S.I.; Arch, D.A.N.; Nylund-Gibson, K. Elementary school teacher well-being and supportive measures amid COVID-19: An exploratory study. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 36, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, C.J.; McGrew, J.; Ruble, L.; Fischer, M. Socially distanced teaching: The mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on special education teachers. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 50, 1768–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Fu, P.; Li, X.; Li, M.; Zhu, M. Trauma exposure and the PTSD symptoms of college teachers during the peak of the COVID-19 outbreak. Stress Health 2021, 37, 914–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flores, J.; Caqueo-Urízar, A.; Escobar, M.; Irarrázaval, M. Well-Being and Mental Health in Teachers: The Life Impact of COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Han, X.; Liu, Y.; Zou, L.; Wen, J.; Yan, S.; Lv, C. Prevalence and Related Factors of Anxiety Among University Teachers 1 Year After the COVID-19 Pandemic Outbreak in China: A Multicenter Study. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 823480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, K.C.; Sebastian, J.; Reinke, W.M.; Huang, F.L. Individual and school predictors of teacher stress, coping, and wellness during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2021, 36, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossain, T.; Islam, A.; Jahan, N.; Nahar, M.T.; Sarker, J.A.; Rahman, M.; Deeba, F.; Hoque, K.E.; Aktar, R.; Islam, M.; et al. Mental Health Status of Teachers During the Second Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Web-Based Study in Bangladesh. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 938230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishak, A.R.; Adnan, N.A.; Aziz, M.Y.; Nazl, S.N.; Mualif, S.A.; Ishar, S.M.; Suaidi, N.A.; Aziz, M.Y.A. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Among Teachers in Malaysia: A Cross-sectional Study. Malays. J. Med. Health Sci. 2022, 18, 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Jelińska, M.; Paradowski, M.B. The Impact of Demographics, Life and Work Circumstances on College and University Instructors’ Well-Being During Quaranteaching. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 643229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovac, F.; Memisevic, H.; Svraka, E. Mental Health of Teachers in Bosnia and Herzegovina in the Time of COVID-19 Pan-demics. Mater. Socio Med. 2021, 33, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotowski, S.E.; Davis, K.G.; Barratt, C.L. Teachers feeling the burden of COVID-19: Impact on well-being, stress, and burnout. Work 2022, 71, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukreti, S.; Ahorsu, D.K.; Strong, C.; Chen, I.-H.; Lin, C.-Y.; Ko, N.-Y.; Griffiths, M.D.; Chen, Y.-P.; Kuo, Y.-J.; Pakpour, A.H. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Chinese Teachers during COVID-19 Pandemic: Roles of Fear of COVID-19, Nomophobia, and Psychological Distress. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koestner, C.; Eggert, V.; Dicks, T.; Kalo, K.; Zähme, C.; Dietz, P.; Letzel, S.; Beutel, T. Psychological Burdens among Teachers in Germany during the SARS-CoV-2 Pandemic—Subgroup Analysis from a Nationwide Cross-Sectional Online Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Chen, H.; Xu, J.; Wen, Y.; Fang, T. Exploring the Relationships between Resilience and Turnover Intention in Chinese High School Teachers: Considering the Moderating Role of Job Burnout. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lizana, P.A.; Lera, L. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress among Teachers during the Second COVID-19 Wave. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maung, T.M.; Tan, S.Y.; Tay, C.L.; Kabir, M.S.; Shirin, L.; Chia, T.Y. Mental Health Screening during COVID-19 Pandemic among School Teachers in Malaysia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushita, M.; Yamamura, S. The Relationship Between Long Working Hours and Stress Responses in Junior High School Teachers: A Nationwide Survey in Japan. Front. Psychol. 2022, 12, 775522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikušková, E.B.; Verešová, M. Distance Education during COVID-19: The Perspective of Slovak Teachers. Probl. Educ. 21st Century 2020, 78, 884–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milić, S.; Marić, N. Concerns and mental health of teachers from digitally underdeveloped countries regarding the reopening of schools after the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Work 2022, 71, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabe-Nielsen, K.; Fuglsang, N.V.; Larsen, I.; Nilsson, C.J. COVID-19 Risk Management and Emotional Reactions to COVID-19 Among School Teachers in Denmark. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2021, 63, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabe-Nielsen, K.; Christensen, K.B.; Fuglsang, N.V.; Larsen, I.; Nilsson, C.J. The effect of COVID-19 on schoolteachers’ emotional reactions and mental health: Longitudinal results from the CLASS study. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2021, 95, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Espinosa, J.A.; Vaquero-Abellán, M.; Perea-Moreno, A.-J.; Pedrós-Pérez, G.; Aparicio-Martínez, P.; Martínez-Jiménez, M.P. The Influence of Technology on Mental Well-Being of STEM Teachers at University Level: COVID-19 as a Stressor. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N.; Berasategi Santxo, N.; Idoiaga Mondragon, N.; Dosil Santamaría, M. The Psychological State of Teachers During the COVID-19 Crisis: The Challenge of Returning to Face-to-Face Teaching. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 620718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palma-Vasquez, C.; Carrasco, D.; Hernando-Rodriguez, J. Mental Health of Teachers Who Have Teleworked Due to COVID-19. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2021, 11, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randall, K.; Ford, T.G.; Kwon, K.-A.; Sisson, S.S.; Bice, M.R.; Dinkel, D.; Tsotsoros, J. Physical Activity, Physical Well-Being, and Psychological Well-Being: Associations with Life Satisfaction during the COVID-19 Pandemic among Early Childhood Educators. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 9430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seyahi, E.; Poyraz, B.Ç.; Sut, N.; Akdogan, S.; Hamuryudan, V. The psychological state and changes in the routine of the patients with rheumatic diseases during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in Turkey: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Rheumatol. Int. 2020, 40, 1229–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigursteinsdottir, H.; Rafnsdottir, G.L. The Well-Being of Primary School Teachers during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, P.S.; Urbano, R.L.; Castelao, S.R. Consequences of COVID-19 Confinement for Teachers: Family-Work Interactions, Technostress, and Perceived Organizational Support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachteas, P.; Stachteas, C. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on secondary school teachers. Psychiatriki 2020, 31, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Tarimo, C.S.; Wu, C.; Miao, Y.; Wu, J. Prevalence and risk factors of worry among teachers during the COVID-19 epidemic in Henan, China: A cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e045386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yuan, X.; Huang, H.; Li, Y.; Yu, H.; Chen, X.; Luo, J. The Prevalence and Correlative Factors of Depression Among Chinese Teachers During the COVID-19 Outbreak. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 644276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Yao, B. Social support and acute stress symptoms (ASSs) during the COVID-19 outbreak: Deciphering the roles of psychological needs and sense of control. Eur. J. Psychotraumatology 2020, 11, 1779494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, E.C.; Espinosa, M.M.; Marcon, S.R.; Reiners, A.A.O.; Valim, M.D.; Alves, B.M.M. Factors associated with health dissatisfaction of elementary school teachers. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2020, 73, e20190832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, S.J.; Sen, D.; McNamee, R. Risk factors for work-related stress and health in head teachers. Occup. Med. 2008, 58, 584–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Varol, Y.Z.; Weiher, G.M.; Wendsche, J.; Lohmann-Haislah, A. Difficulties detaching psychologically from work among German teachers: Prevalence, risk factors and health outcomes within a cross-sectional and national representative employee survey. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agyapong, B.; Obuobi-Donkor, G.; Burback, L.; Wei, Y. Stress, Burnout, Anxiety and Depression among Teachers: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dosil Santamaría, M.; Idoiaga Mondragon, N.; Berasategi Santxo, N.; Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N. Teacher stress, anxiety and depression at the 155 beginning of the academic year during the COVID-19 pandemic. Glob. Ment. Health 2021, 8, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Miao, Y.; Zeng, X.; Tarimo, C.S.; Wu, C.; Wu, J. Prevalence and factors for anxiety during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic among the teachers in China. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 277, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, R.M.; Da Rocha, R.E.R.; Andreoni, S.; Pesca, A.D. Retorno ao trabalho? Indicadores de saúde mental em professores durante a pandemia da COVID-19. Polyphonía 2020, 31, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, H.; Chen, R.; Hu, W.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, X. Remote monitoring contributes to preventing overwork-related events in health workers on the COVID-19 frontlines. Precis. Clin. Med. 2020, 3, 97–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressley, T.; Ha, C.; Learn, E. Teacher stress and anxiety during COVID-19: An empirical study. Sch. Psychol. 2021, 36, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, V. Language anxiety and the online learner. Foreign Lang. Ann. 2020, 53, 338–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.; Liang, L.; Chutiyami, M.; Nicoll, S.; Khaerudin, T.; Van Ha, X. COVID-19 pandemic-related anxiety, stress, and depression among teachers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Work 2022, 73, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozamiz-Etxebarria, N.; Mondragon, N.I.; Bueno-Notivol, J.; Pérez-Moreno, M.; Santabárbara, J. Prevalence of Anxiety, Depression, and Stress among Teachers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Rapid Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, R. Impact of Societal Culture on Covid-19 Morbidity and Mortality across Countries. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2021, 52, 643–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author (Year)-Quality of Studies | Study Type | Pathology Condition Assessed | Scales Used | Main Results | Study Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akour et al., 2020 [16] - Good | Cross-sectional | Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) | Author questionnaire with a five-point Likert scale; Kessler Distress Scale (K10) | The younger you are, the more likely you are to develop generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). University professors with low motivation for distance learning are 1.42 times more likely to experience moderate to severe GAD than the reference category. There were 344 subjects (90.1%) reported not using any medication in response to the COVID-19-induced psychological impact, while 38 respondents (9.9%) reported using different medications and sedative–hypnotic drugs. Most subjects (69.6%) faced varying degrees of GAD amid the current pandemic. | Small and non-randomized sample; Self-report questionnaire; The sample was composed for teachers from more developed urban areas; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Amri et al., 2020 [17] - Good | Cross-sectional | Burnout Syndrome | Author questionnaire; Maslach Burnout Inventory | 54% of the teachers had burnout. 38% experienced mild burnout, 12% moderate, and 6% severe. | Small and non-randomized sample; Self-report questionnaire; Impossibility of assessing causality. |

| Baker et al., 2021 [18] - Good | Cross-sectional | Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) | Author questionnaire | As for their overall mental health since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, most teachers reported that it was between “fair” and “good” (M = 2.84, SD = 1.05). Black teachers reported better mental health than white teachers (p < 0.001). Mental health was predictably inversely associated with coping and learning outcomes. | Self-report questionnaire; Use of non-validated questionnaire; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Cataudella et al., 2021 [19] - Good | Cross-sectional | Self-esteem; Self-efficacy | Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale; Four-point Likert scale; Teacher’s Self-Efficacy Scale | The results showed lower self-esteem and lower self-efficacy on the part of teachers compared to the normative sample. They were also lower in teachers with more years of work. The teachers perceived a greater difficulty among the students than among them. | Small and non-randomized sample; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Chan et al., 2021 [20] - Good | Cross-sectional | Emotional exhaustion; Stress | Maslach Burnout Inventory Educators Survey; 5-point Likert scale; Teacher Stress Inventory job satisfaction subscale; Teacher’s Subjective Well-Being Questionnaire; Teaching Autonomy Scale; Revised Teacher Stress Inventory Subscales | A total of 50% of the respondents reported feeling emotionally challenged about their teaching experience frequently since school closing. A total of 59% of the subjects felt the stress of the daunting task more than ‘sometimes’. Over 51% of the respondents felt unclear about their job duties and expectations more than ‘sometimes’, and 22.3% of the respondents felt satisfied with their jobs less frequently than ‘sometimes’ during school closures. Task stress had a robust and positive association with emotional exhaustion, but not with job satisfaction. Role ambiguity was negatively associated with job satisfaction, but not significantly associated with emotional exhaustion. All three job resources showed significant and positive associations with job satisfaction. In addition, school connection was negatively associated with emotional exhaustion. | Non-representative sampling study; Restricted to a large center in the US; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Chen et al., 2020 [8] - Good | Cross-sectional | Burnout syndrome | Teacher Professional Identity Scale; Job Satisfaction Scale; Burnout Scale at Work | Teachers’ professional identity and job satisfaction are significantly negative predictors of burnout at work, with job satisfaction playing a moderating role between professional identity and burnout at work. Professional identity and job satisfaction are important factors that affect the work strain of university professors. | Use of online questionnaire for research; Small sample with only university teachers; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Cormier et al., 2021 [21] - Good | Cross-sectional | Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD); Depression; Anxiety; Emotional exhaustion; Depersonalization; Personal fulfillment Burnout syndrome | Maslach Burnout Inventory—Educators Survey (MBI-ES); 7-point Likert scale; Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9); Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7); Teacher-Specific Stress | A total of 38.4% met clinical criteria for generalized anxiety disorder, a rate 12.4 times higher than that of the US population, and 37.6% for major depressive disorder, a rate 5.6 times higher than that of the population. The impact of the pandemic was moderate to severe on stress (91%), depression (58%), anxiety (76%), and emotional exhaustion (83%). | Use of online and self-report questionnaire for research; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Fan et al., 2021 [22] - Good | Cross-sectional | PTSD; Anxiety; Intrusion; Avoidance; hyperarousal | Author questionnaire; Impact of Event Scale-Revised for PTSD symptoms | The results showed that the overall incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder among college professors was as high as 24.55%, but the mean level of PTSD scores was low. Compared with those without symptoms, the proportion of PTSD increased by 181%. For those who had family members or relatives who died from COVID-19, the proportion was 459% higher than those who had no loss. The results showed that approximately 1/4 of university professors in Wuhan developed PTSD, but the level of PTSD was low | Addresses only one class of teachers Use of online and self-report questionnaire for research; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Flores et al., 2022 [23] - Fair | Cross-sectional | Depression; Anxiety; Stress; Satisfaction with life; Concerns; Social relationships; Economic situation; Work and family life | Escala de Diener, Emmons, Larsen e Griffin Brief Multidimensional Student Satisfaction with Life Satisfaction Scale DASS-21 Escala Breve de Espiritualidade | Spirituality and the use of self-applied socio-emotional strategies by teachers were not directly related to their mental health, so their mediating effect in relation to life satisfaction was discarded. Teachers who used social-emotional strategies, as well as those who reported higher levels of spirituality, had greater satisfaction with life, both generally and specifically. Women showed higher levels of symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress, but also higher levels of satisfaction with life. | Non-randomized sample; Use of online and self-report questionnaire for research; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Fu et al., 2022 [24] - Good | Cross-sectional | GAD | Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7); Multidimensional Perceived Social Support Scale (MSPSS) | One year after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the overall prevalence of anxiety was 40.0%, being higher in women than in men. Being female, age ≥60 years, being married, and poor family economic status were significantly associated with anxiety. Participants with moderate, mild, or no impact of COVID-19 on their lives showed a reduced risk of anxiety compared to those who reported a significant effect. Anxiety symptoms were found in about two-fifths of Chinese university professors 1 year after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. | Use of online and self-report questionnaire for research; Only public universities; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Herman et al., 2021 [25] - Good | Cross-sectional | Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) Depression | General health and job satisfaction scales; Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2); Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2); Authoritative School Climate Survey (ASCS) | Teachers reported job stress levels above the midpoint, indicating that their jobs were more stressful, and they also reported values showing high levels of job stress. The mean values of teachers’ job satisfaction and general health status were positive. As for depression and GAD, 9% of teachers reported scores above the cutoff on the PHQ-2, indicating that major depression was likely, and 16% of the teachers reported scores above the cutoff on the GAD-2, indicating a probable risk for GAD. | Possibility of memory bias; Impossibility of assessing causality. |

| Hilger et al., 2021 [14] - Good | Longitudinal research | Autonomy; Social support; Fatigue; Claims; Job satisfaction; Stress; Affectivity | Author questionnaire with a 7-point Likert scale; Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire; Subscale of Emotional Work Demands; Quantitative Workload Inventory; Scale of Interpersonal Conflict at Work; Work Demand Questionnaire; Three-Dimensional Work Fatigue Inventory Freiburg; Bodily Complaints Inventory | Both work demands and work resources have decreased compared to the period prior to COVID-19. Furthermore, we found simultaneous changes in work-related well-being in terms of decreased fatigue. No overall changes were found for psychosomatic symptoms, complaints, and job satisfaction. Work demands and work resources differentially impacted well-being, while changes in work demands—but not work resources—were related to negative well-being (fatigue and psychosomatic complaints). Changes in work resources, but not work demands, were associated with changes in positive indicators of well-being (job satisfaction). | Original study design was not for assessing the impact of the covid-19 pandemic; Use of online and Self-report questionnaire for research; Possibility of memory bias. |

| Hossain et al., 2022 [26] - Good | Cross-sectional | Depression; Anxiety; Stress; Fear | DASS-21 Author questionnaire | The results indicate that the overall prevalence of depression, anxiety and stress among teachers was 35.4%, 43.7% and 6.6%, respectively. Prevalence was higher among male and older teachers than among female and younger colleagues. The results also showed that the place of residence, the institution, self-reported health, use of social and electronic media, and fear of COVID-19 significantly influenced the mental health status of teachers. University professors showed less depression compared to primary school professors. The results showed that teachers aged 31–40 years old and 41 years old or older were less stressed compared to teachers younger than 30 years old. | Small and non-randomized sample; Use of online and self-report questionnaire for research; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Ishak et al., 2022 [27] - Good | Cross-sectional | Depression; Anxiety; Stress; Quality of life; Dysphoria; hopelessness; Self-depreciation; Nervousness; Difficulty sleeping; physical functioning | DASS-21; SF-36 Health Survey Questionnaire (SF-36); Author questionnaire | According to the findings of this study, most teachers (55.5%) were anxious, followed by depression (39.9%) and stress (27.6%). Depression, anxiety and stress were all statistically related to age, marital status and number of children. When it comes to quality of life, teachers had the highest physical functioning score at around 86 but the lowest vitality at 62.3. All domains of quality of life were negatively correlated with depression, anxiety and stress. | Small and non-randomized sample; Use of online and self-report questionnaire for research; Only teachers from primary and secondary schools; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Jakubowski, Sitko-Dominik, 2021 [13] - Good | Retrospective research | Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD); Depression | The Depression Anxiety & Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21); The Berlin Social Support Scales (BSSS); The Relationship Satisfaction Scale (RS-10); The Injustice Experience Questionnaire (IEQ) | The disorders were more prevalent in the second wave of the pandemic in Poland. Stress ranged from 6% in the first stage of the survey to 47% in the second stage. Anxiety and depression ranged from 21 to 31% and from 12% to 46% between waves, respectively. | The first phase of the study was retrospective and the second was cross-sectional; Possibility of memory bias; Non-homogeneity in the sample analyzed between the first and second steps. |

| Jelińska, Paradowski, 2021 [28] - Good | Cross-sectional | Sadness; Irritation; Willingness; Emotional instability; Fatigue; Loneliness | 23 short scales were developed from the International Personality Item Pool [IPIP]; Six-point Likert scale; Perceived Stress Scale (PSS); Self-Compassion Scale | Negative affect was significantly and positively correlated with greater situational generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (r = 0.47) and situational loneliness (r = 0.36). Furthermore, the stronger the negative emotional state, the less teachers reported work–life synergy (r = –0.43) and the less productive they felt (r = –0.33) during the pandemic. Finally, those who felt more negative emotions were also coping worse than others (r = –0.30). The most influential predictor of teachers’ negative emotional states was anxiety (p < 0.001), explaining approximately 22% of the variation in negative affect. | Self-selection biases of participants: use of an online questionnaire (deprives those who do not have access to the internet), selects those who would be motivated to participate or identify with the theme; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Kovac et al., 2021 [29] - Good | Cross-sectional | Depression; Anxiety; Stress | DASS-21 | High prevalence of high levels of depression (31.5%), anxiety (39%) and stress (19%). Teachers have a high prevalence of high levels of depression, anxiety and stress. Teachers have a higher level of depression, anxiety and stress than male teachers. There was no difference in depression, anxiety, and stress between elementary school teachers and high school teachers. Protective factors for depression, anxiety, and stress are levels of family support, school administration support, and student understanding. Depression, anxiety and stress levels were not statistically different in vaccinated and unvaccinated teachers. | Non-randomized and not representative sample; Only elementary school teachers and high school teachers; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Kotowski et al., 2022 [30] - Good | Cross-sectional | Stress; Exhaust; Welfare; Burnout | Author questionnaire | Stress and burnout remain high for teachers, with 72% of teachers feeling very or extremely stressed and 57% feeling very or extremely drained. Many teachers struggle to have a satisfactory work–family balance (37% never or almost never; 20% only sometimes) | Inability to establish causality by study design; Sample selected for convenience; Use of a self-administered and online questionnaire. |

| Kukreti et al., 2021 [31] - Good | Cross-sectional | Post-traumatic stress disorder; Nomophobia; Fear; Psychological suffering; Depression; Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) | PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5); Fear of COVID-19 PTSD Scale; Chinese COVID-19 Fear Scale (FCV-19S) of seven items; 20-item Chinese Nomophobia Questionnaire; Chinese Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) | With the cutoff score of 31, the prevalence of PTSD was 12.3%, but decreased to 1.0% when the cutoff score was 49. Fear of COVID-19 among teachers leads to PTSD due to psychological distress, highlighting the moderating effect of nomophobia in this association. | Inability to establish causality by study design; Sample selected for convenience; Use of a self-administered and online questionnaire. |

| Koestner et al., 2022 [32] - Good | Cross-sectional | Emotional exhaustion; Depersonalization; Anxiety; Depression | Validated German version of the Patient Health Questionnaire 4; Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI); Author questionnaire | The psychological burden on German teachers exceeded the level of the general population, for example, in relation to symptoms of depression or generalized anxiety. Subgroup analysis revealed that psychological burdens were unequally distributed among different groups of teachers; Younger teachers (18–30 years old) had more symptoms of depression compared to their older colleagues (56–67 years old) | Inability to establish causality by study design; Sample selected for convenience; Use of a self-administered and online questionnaire. |

| Liu et al., 2021 [33] - Good | Cross-sectional | Resilience; Professional exhaustion; Intention of turnover; Burnout; Confidence; Optimism; Force | Resilience Scale developed by Connor and Davidson; Work exhaustion scale; Rotation intention scale | Burnout had a significant positive predictive effect on turnover intention (r = 0.485, p < 0.05). At the same time, job burnout played a moderating role in resilience and turnover intention (p < 0.001). Resilience and its dimensions of confidence, strength, and optimism had a significant negative correlation with turnover intent, and resilience could significantly predict turnover intent negatively. | Sample restricted to one region; Use of non-validated scales for the purpose of the study; Use of a self-administered and online questionnaire for the government system. |

| Lizana et al., 2021 [15] - Fair | Longitudinal research | Feelings (uncertainty, loneliness, fear, role limitations due to emotional problems and mental health) | Short-Form 36 Health Survey (SF-36) questionnaire. | Quality of life showed a significant decrease during the pandemic compared to the pre-pandemic measure (p < 0.01). In each gender, there were significant differences between the pre-pandemic and pandemic times, with a greater impact among women in the summary variables of the mental and physical component and in seven of the eight quality of life scales (p < 0.01). Across age categories, people under 45 showed significant differences between pre-pandemic and pandemic times across all summary dimensions and measures. | Use of online and Self-report questionnaire for research; Sample size. |

| Lizana, Lera, 2022 [34] - Good | Cross-sectional | Depression; GAD; Stress | DASS-21 | High rates of symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress were observed among teachers (67%, 73% and 86%, respectively). Among teachers affected by work–family balance (89%), there was also an increased risk of symptoms of anxiety (OR: 3.2) and stress (OR: 3.5). The risk of depression symptoms was higher among females (OR: 2.2), and teachers under 35 years of age were at risk of having all three symptoms (depression OR: 2.2; anxiety OR: 4.0; stress OR 3.0). | Small and non-randomized sample; Only teachers from primary and secondary schools; Use of online and self-report questionnaire for research; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Maung et al., 2022 [35] - Good | Cross-sectional | Depression; GAD; Stress | DASS-21; Author questionnaire | The percentages of respondents with mild, moderate, severe, and extremely severe depression were 12%, 9.7%, 4.7%, and 3.1%, respectively. Those with mild, moderate, severe, and extremely severe anxiety accounted for 11.5%, 12.3%, 6.3%, and 6%, respectively. Those with mild, moderate, severe and very severe stress accounted for 12.8%, 12%, 5.3% and 20.5%, respectively. Perceived overwork was significantly higher during the pandemic compared to before the pandemic. Significant teaching experience and less perceived overwork before and during the pandemic were associated with better mental health. | Only primary and secondary school teachers; Small and non-randomized sample; Use of online and self-report questionnaire for research; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Matsushita, Yamamura, 2021 [36] - Good | Cross-sectional | Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) Reliability; Irritability; Fatigue | Brief Job Stress; Author questionnaire | A total of 59.6% of the subjects worked 11 h or more a day, with significant differences in workload between positions. Regarding effective teachers, gender (female), age, class tenure, number of years working in the same school, working hours of more than 10 h were significantly associated with high stress, compared to those who worked less than 9 h per day. | Non-randomized sample; Addresses only one class of teachers Use of online and self-report questionnaire for research; Impossibility to deduce causality of the relationship between long working hours and stress responses. |

| Mikušková, Verešová 2020 [37] - Good | Cross-sectional | Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) Satisfaction; Expectation | 6 point scale; Positive and Negative affect Schedule (PANAS); Big Five Inventory (BFI-2) | During the pandemic period, teachers’ negative emotions increased, while positive ones decreased; distance education was closely related to emotions (and changes in emotions) and personality; In addition, teachers reported willingness to implement partial changes in their teaching after the pandemic period. | Small and non-randomized sample; Use of online and self-report questionnaire for research; Only primary school and upper-secondary school teachers; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Milić, Marić, 2022 [38] - Good | Cross-sectional | GAD | Author questionnaire; GAD-7 | On the GAD-7 scale, the arithmetic mean of the examined population is 0.64 (SD 1.22), which indicates a normal degree of anxiety in the examined population. Only 2% of teachers had mild anxiety. Moderate and severe anxiety were not reported. | Small sample, non-randomized; Only primary school and upper-secondary school teachers; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Nabe-Nielsen et al., 2020 [39] - Good | Cross-sectional | Fear | Author questionnaire | The prevalence of concern about going to work was higher among those who were solely responsible for remote teaching (34%) than among those who taught at school (19%). Other emotional reactions, that is, fear of contagion and transmission of infections, were equally frequent among those who carried out face-to-face teaching at school and those who carried out online remote teaching. | Addresses only public school teachers; Use of an online, non-validated and self-administered questionnaire for research. Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Nabe-Nielsen et al., 2021 [40] - Fair | Longitudinal research | Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) Exhaustion; Fear; Burnout syndrome | Author questionnaire | Emotional reactions and poor mental health increased significantly from 27 to 84% from May to November and December 2020. Teachers, particularly vulnerable to the adverse consequences of COVID-19 had the highest prevalence of fear of infection and poor mental health. Teachers who reported being part of a COVID-19 risk group had a higher level of emotional reactions and poor mental health at most measurement points. | Addresses only public school teachers; Use of an online, non-validated and self-administered questionnaire for research. |

| Navarro-Espinosa et al., 2021 [41] - Good | Cross-sectional | Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) Depression; Technostress | Anxiety and Risk of Depression Scales; Rosenberg’s subscales of anxiety and depression risk | The risk of developing anxiety among teachers was 85.5%, with a similar frequency between the Spaniards (83.3%) and Ecuadorians (86.5%). The risk of developing anxiety showed significant differences in the role of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) in education and the lack of ICTs (p < 0.05). In addition, COVID-19 as a stressor showed a significant difference between teachers at risk of anxiety (82.98%), while the risk of depression was related to COVID-19 as a stressor (p = 0.037), the balance between family and work (p = 0.006), availability of computers and internet, role of ICT in education, lack of models and time (p < 0.05). 85% of the college professors were at risk of developing anxiety, which was also linked to depression. | Small sample; Use of online and self-report questionnaire for research; Only university teachers and specific knowledge are; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020 [42] - Good | Cross-sectional | Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) Anxiety; Depression | Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21) | A total of 50.6% of the teachers indicated suffering from stress, with 4.5% reporting extremely intense stress and 14.1% severe stress. About 49.5% of the teachers reported suffering from anxiety, of which 8.1% reported extremely severe symptoms and 7.6% severe symptoms. Finally, 32.2% of the teachers reported suffering from depression, of which 3.2% reported extremely severe symptoms and 4.3% severe symptoms. | Self-report questionnaire for research; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Palma-Vasquez, Carrasco, Hernando-Rodriguez, 2021 [43] - Good | Cross-sectional | Depression; Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) Diverse feelings | General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12); Likert Scale; Score scale corrected using Cronbach’s alpha | The prevalence of poor mental health among teachers was 58.27%. The risk of having worse mental health was higher for those who worked two or more unpaid overtime hours a day compared to those who did not have to extend their work hours during the pandemic. Being absent due to illness was associated with a 282% greater likelihood of having mental health issues compared to not being absent during 2020. | Small, non-randomized sample; Only teachers who teleworked more than 50% during the 2020 academic year; Use of online and self-report questionnaire for research; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Panisoara et al., 2020 [9] - Good | Cross-sectional | Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation; Occupational stress (Burnout and technostress); Self-efficacy, burnout | Author questionnaire with a seven-point Likert scale; Work Tasks Motivation Scale for Teachers (WTMST); Oldenburg Burnout Inventory (OBI); Learning Misfit Scale; Person-Technology Enhanced (P-TEL); Continuation Intent Scale (CI) | The structural model accounted for 70% of the variation in teachers’ intention to stay using online teaching and for 51% of the variation in teachers’ burnout and technostress. Extrinsic motivation significantly amplifies occupational stress, represented by negative feelings about online teaching, while intrinsic motivation significantly diminishes them, even if with less intensity. | Use of online and self-report questionnaire for research; The experimental part of the study was carried out in a relatively short time frame; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Randall et al., 2021 [44] - Good | Cross-sectional | Physical well-being; Psychological well-being; Professional well-being; Work demands and life satisfaction during the pandemic; Satisfaction with life; depressive symptoms; Stress resilience; Secondary trauma | International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ); Short Last 7 Days Self-administered format; SF-12 Health Survey Standard, Version 1; Musculoskeletal Disorders Scale; Related to Work (WMDS); Life Satisfaction Scale; Center for the Epidemiological Studies of Depression 10-item Short Form (CES-D-10); Perceived Stress Scale (PSS); Brief Resilience Scale; Professional Quality of Life Scale subscales; Early Childhood Job Satisfaction Survey (ECJSS); Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ); Author questionnaire Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS); Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) | Of the respondents, 77% were overweight or obese and only 39% met the recommendation of 150 min of moderate physical activity per week. They had an average life satisfaction score that qualifies as mild satisfaction, experienced moderate stress, and were collectively approaching the threshold for depression, but still reflected moderate to high work commitment. | Only early care and education teachers; Non-randomized sample; Use of online and self-report questionnaire for research; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Seyahi et al., 2020 [45] -Good | Cross-sectional | Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) Depression; Post-Traumatic Stress; Sleep problems | International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ); Short Last 7 Days Self-administered format; SF-12 Health Survey Standard, Version 1; Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders (WMDs); Life Satisfaction Scale; Center for the Epidemiological Studies of Depression 10-item Short Form (CES-D-10); Perceived Stress Scale (PSS); Brief Resilience Scale; Professional Quality of Life Scale subscales; Early Childhood Job Satisfaction Survey (ECJSS); Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ); Author questionnaire Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS); Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) | A total of 23.1% of the teachers had generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), 47.7% depression, and 29.1% post-traumatic stress symptoms. | Non-randomized sample; Selected group (patients with rheumatic diseases) Use of online and self-report questionnaire for research; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Sigursteinsdottir, Rafnsdottir, 2022 [46] - Fair | Longitudinal | GAD; Physical symptoms of tiredness; Sadness | 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) Author questionnaire | Results show increased stress, worse mental and physical health, and increased mental and physical symptoms in 2021 compared to 2019. Worse mental health and mental health symptoms were the strongest predictors of high levels of stress. The interaction between time of study and mental health symptoms indicated that the influence of time was greater for teachers who reported mental health symptoms than for others. In other words, the COVID-19 pandemic was negatively correlated with these health and well-being factors, indicating the deterioration of teachers’ health and well-being. The proportional stress level increased by about 10% in 2021 compared to 2019, and the result revealed that 28% of teachers were categorized with high stress. | Only primary school teachers; Use of online and self-report questionnaire for research; Without confirmation by physicians. |

| Solís García et al., 2021 [47] - Good | Cross-sectional | Fatigue; Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) Skepticism; Ineffectiveness | Survey Work-Home Interaction-Nijmegen (SWING); RED-ICT Technostress Questionnaire | Negative work–family interaction correlated with ineffectiveness (r = 0.12), skepticism (r = 0.09), fatigue (r = 0.96), and anxiety (r = 0.47). On the other hand, the family-work interaction was significantly correlated with the variables of ineffectiveness (r = 0.20), skepticism (r = 0.14), fatigue (r = 0.47), and anxiety (r = 1). | Only pre-school, primary, and secondary school teacher; Use of online and self-report questionnaire for research; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Souza e Silva e tal, 2021 [10] - Good | Cross-sectional | Insatisfação com o trabalho; Ansiedade; Depressão; Problemas de sono; Aumento do consumo de álcool; Medo da COVID-19 | Author questionnaire | A total of 25.9% of teachers reported a formal diagnosis of anxiety and/or depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, 7.1% of the teachers were drinking more alcohol than usual, 33.4% started having sleep problems, 30.4% were using drugs to relax/sleep/anxiety/depression, the perception of quality of life of 67.1% of teachers worsened and 43.7% reported having severe fear of COVID-19. Up to 82.3% of teachers had at least one condition related to mental health during the pandemic, such as increased alcohol consumption, sleep problems, use of psychotropic medication, quality of life, and fear of COVID-19. Most of the teachers reported a decrease in their quality of life during the pandemic. More than a quarter of the teachers in our study reported having received a formal diagnosis for anxiety and/or depression during the pandemic. | Only public school teacher; Use of online and self-report questionnaire for research; Self-report response, leading to the possibility of memory bias; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Stachteas, Stachteas, 2020 [48] - Good | Cross-sectional | Fear, Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), optimism about the outcome, depression, desire to return to work, concern about the implementation of distance learning. | Author questionnaire with a 6-point Likert scale | A total of 34% of the teachers experienced a high and very high level of fear during the pandemic. The existence of an underage child in the family affects the experience of fear concerning the development of the pandemic. There is a correlation between gender and the emergence of feelings of fear, depression, and optimism. Women showed the highest levels of fear and depression, while the situation is the opposite when it comes to optimism. The optimism expressed also depends on education. Most teachers (60.6%) are moderately optimistic. Depression was correlated with sex, prevailing in lower-class men (69.9%). | Study included only/secondary school teachers, which makes it impossible to generalize; Small sample; Use of an online, non-validated and self-administered questionnaire for research. |

| Wang et al., 2021 [49] - Good | Cross-sectional | Attention level; Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) Fear level; Behavior status to alleviate worry | Author questionnaire with a five-item Likert scale Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) | A total of 59% of the teachers reported being ‘very worried’ about the pandemic. The proportion of female professors was higher than that of male professors (60.33% vs. 52.89%). In all age groups, the condition “very worried” represented the highest proportion. The 40–49 age group had the lowest proportion of very concerned subjects. | Use of online and self-report questionnaire for research; Inability to establish causality by study design. |

| Zhou et al., 2021 [50] - Good | Cross-sectional | Mental resilience Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) Depression Sleep duration | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9); Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale 25 (CD-RISC 25); Perceived Stress Scale-10 (PSS-10) | A total of 624 (56.9%) suffered from depression and 177 (16.1%) suffered from moderate to severe depression; 17 (10.7%) teachers had low mental resilience and 1053 (96.1%) teachers had a high perception of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). | Use of online and self-report questionnaire for research; Inability to establish causality by study design; Study did not take into account important factors that influence depression, such as presence/absence of social support and physical activity. |

| Zhou, Yao, 2020 [51] - Good | Cross-sectional | Psychological states; Acute Stress Disorder | Received Social Support Questionnaire; Sheldon and Niemiec’s Basic Psychological Needs Scale; Subscale Sense of Control on the Feelings of Security Scale; DSM-5; Acute Stress Disorder Diagnostic Criteria B | A total of 68 (9.1%) subjects were identified as having probable ASD. The prevalence of acute stress symptoms in teachers is 9.1%. Social support had a negative indirect relationship with the Social support and acute stress symptoms through the need for autonomy or relationship, but not the need for competence. | Study included only primary/secondary school teachers, which makes it impossible to generalize; Inability to establish causality by study design; Assessment of only one group of factors (psychosocial) in the outcome. |

| Author (Year) - Country - Total Sample (n) | Female (n, %) - Age (Mean, Age Group or %) | Category of Teachers - Teaching Experience (Years) | Generalized Anxiety Disorder (n, % or M and SD) | Post- Traumatic Stress Disorder (n, % or M and SD) | Depressive Disorder (n, % or M and SD) | Burnout Syndrome (n, % or M and SD) | Psychiatric Illnesses before COVID-19 (n, %) | Work-Family Conflicts (n, %) - Family Support (n, %) - Social Support (n, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akour et al., 2020 [16] - Jordan - 383 | 212 (55%) - 34–52 y | High - 1–53 y | 120 (31.7%) | NA | NA | NA | 14 (3.7%) | NA - 240 (62.8%) - 190 (49.7%) |

| Amrir et al., 2020 [17] - Morocco - 125 | 71 (65.8%) - 25–59 y | Elementary - 5–21 y | NA | NA | NA | 67 (54%) | NA | 70 (56%) - NA - 23 (18.4%) |

| Baker et al., 2021 [18] - US - 454 | 366 (80.6%) - 18–64 y | Elementary, Middle and High - 1–20 y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA - NA - 68 (15%) |

| Cataudella et al., 2021 [19] - Italy - 226 | 199 (88.1%) - 35–55 y | Elementary and High - 15 y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA - NA - NA |

| Chan et al., 2021 [20] - US - 151 | 120 (80.8%) - NA | Elementary - 2–46 y | 89 (59%) | NA | NA | 75 (50%) | NA | NA - NA - NA |

| Chen et al., 2020 [8] - China - 483 | NA - NA | High - NA | NA | NA | NA | 253 (52.4%) | NA | NA - NA - NA |

| Cormier et al., 2021 [21] - US - 468 | 415 (88.3%) - 43 y | Elementary and High - 32–54 y | 178 (38%) | NA | 275 (37.3%) | 388 (83%) | NA | NA - NA - NA |

| Fan et al., 2021 [22] - China - 1650 | 855 (51.8%) - 32–48 y | High - NA | NA | 24.55% | NA | NA | NA | NA - NA - NA |

| Flores et al., 2022 [23] - Chile - 624 | 464 (74.4%) - 33–55 y | NA - NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA - NA - NA |

| Fu et al., 2022 [24] - China - 10,302 | 5760 (41.3%) - 18–60 y | High - 1–30 y | 2380 (40%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA - 6761 (65.6%) - 2976 (28.8%) |

| Herman et al., 2021 [25] - US - 639 | 492 (77%) - NA | Elementary, Middle and High - 1–10 y | 100 (16%) | NA | 57 (9%) | NA | NA | NA - NA - NA |

| Hilger et al., 2021 [14] - German - 207 | 175 (85%) - 24–66 y | Elementary and Middle - 1–36 y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA - NA - NA |

| Hossain et al., 2022 [26] - Bangladesh - 381 | 149 (39.1%) - 30–40 y | Elementary, Middle and High - NA | 43.7% | NA | 35.4% | NA | NA | NA - 336 (88.2%) - NA |

| Ishak et al., 2022 [27] - Malaysia - 391 | 290 (74.2%) - 21–60 y | Elementary and Middle - NA | 156 (55.5%) | NA | 217 (39.9%) | NA | NA | NA - 232 (59.3%) - NA |

| Jakubowski, Sitko-Dominik, 2021 [13] - Poland - 285 | Primary school, 130 (89.7%); Secondary school, 121 (86.4%) - 46.76 (primary); 43.76 (secondary) | Elementary and Middle - 19.07 | 21% in the first stage of the research to 31% in the second stage | 6% in the first stage of the research to 47% in the second stage | 12% in the first stage of the research to 46% in the second stage | NA | NA | NA - NA - Negative correlation (stress, anxiety and depression) |

| Jelińska, Paradowski, 2021 [28] - 92 countries - 804 | 578 (71.89%) - 44.1 | High - NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Kovac et al., 2021 [29] - Bosnia and Herzegovina - 559 | 471 (84.2%) - 59 (20–30 y); 211 (31–40 y); 184 (41–50 y); 105 (≥50 y) | Elementary and High - NA | 39% | 19% | 31.5% | NA | NA | More family support is related to lower levels of stress, depression and anxiety. |

| Kotowski et al., 2022 [30] - Greater Cincinnati, Ohio, USA - 703 | 578 (82.2%) - 44.6 y | Elementary, Middle and High - 18.5 y | NA | 72% | NA | 57% | NA | Many teachers struggled to have a satisfactory work–family balance (37% never or almost never; 20% only has sometimes) |

| Kukreti et al., 2021 [31] - China - 2603 | 1865 (71.6%) - NA | Elementary and Middle - 10 or fewer years (56.2%) | NA | NA | 321 (12.3%) | NA | NA | NA |

| Koestner et al., 2022 [32] - Germany - 31,089 | 24,099 (77.5%) - 45.8 y | Elementary, Middle and High - NA | M = 2.59 SD = 1.89 | NA | M = 2.34 SD = 1.65 | NA | NA | NA |

| Liu et al., 2021 [33] - China - 449 | 331 (73.72%) - 36.7 y | High - NA | NA | NA | NA | (M = 26.88, SD = 6.89) | NA | NA |

| Lizana et al., 2021 [15] - Chile - 63 | 45 (71%) - Male = 42.6 y Female = 38.9 y | Elementary and Middle - NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA - NA - NA |

| Lizana, Lera, 2022 [34] - Chile - 313 | 256 (81.79%) - 37.9 y | Elementary and Middle - NA | 230 (73.4%) | 270 (86.2%) | 209 (66.7%) | NA | NA | 279 (89.14%) - NA - NA |

| Maung et al., 2022 [35] - Malaysia - 382 | 318 (83.2%) - 18–Older than 60 y | Elementary and Middle - 14.2 y | Mild: 44 (11.5%) Moderate: 47 (12.3%) Severe: 24 (6.3%) Extremely Severe: 23 (6%) | Mild: 49 (12.8%) Moderate: 46 (12%) Severe: 20 (5.2%) Extremely Severe: 8 (2.1%) | Mild: 46 (12%) Moderate: 37 (9.7%) Severe: 18 (4.7%) Extremely Severe: 12 (3.1%) | NA | NA | NA - NA - NA |

| Matsushita, Yamamura, 2021 [36] - Japan - 54,772 | 23,504 (42.9%) - ≤29 y ≥60 y | Elementary - <3 y (65%) ≥3 y (23,9%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA - NA - NA |

| Mikušková, Verešová 2020 [37] - Slovakia - 379 | 340 (89.7%) - 45.14 y | Elementary and Middle - Primary school (19.56 y); upper-secondary school (17.10 y) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA - NA - NA |

| Nabe-Nielsen et al., 2021 [40] - Denmark - 871 | 675 (78%) - 50–59 y | Elementary, Middle and Secondary - NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA - NA - NA |

| Navarro-Espinosa et al., 2021 [41] - Spain and Ecuador - 55 | NA - NA | High - <10 y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA - NA - NA |

| Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020 [42] - Spain - 1633 | 1293 (79.7%) - 426 y | Elementary, Middle and High - NA | 808 (49.5%) | NA | 526 (32.2%) | NA | NA | NA - NA - NA |

| Palma-Vasquez, Carrasco, Hernando-Rodriguez, 2021 [43] - Chile - 278 | 227 (81.65%) - NA - NA | Elementary and Middle - >10 y | NA | NA | 162 (58.27%) | NA | NA | NA - NA - NA |

| Panisoara et al., 2020 [9] - Romania - 988 | 949 (96.8%) - 20–68 y | NA - NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA - NA - NA |

| Randall et al., 2021 [44] - USA - 1434 | 1409 (98.3%) - 42 y - White (60%) | Elementary - NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA - NA - NA |

| Seyahi et al., 2020 [45] - Turkey - 851 | 526 (61.8%) - 35 y - NA | High - NA | 232 (29.1%) | 363 (42.7%) | 373 (42.7%) | NA | 140 (15.3%) | NA - NA - NA |

| Sigursteinsdottir, Rafnsdottir, 2022 [46] - Iceland - 920 | 759 (82.5%) - 41–50 y - NA | Elementary - 11–20 y | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA - NA - NA |

| Solís García et al., 2021 [47] - Spain - 640 | 462 (72,18%) - 43.54 y | Elementary, Middle and High - NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA - NA - NA |

| Souza e Silva et al, 2021 [10] - Brazil - 15,641 | 12,817 (81.9%) - 41–60 y | Middle and High - 1–10 y | 4044 (25.9%) | NA | NA | NA | 5047 (32.3%) | NA - NA - NA |

| Stachteas, Stachteas, 2020 [48] - Greece - 226 | 143 (63.3%) - <60 y | Middle - NA | NA | NA | 100 (44.4%) | NA | NA | NA - NA - NA |

| Wang et al., 2021 [49] - China - 99,611 | 41,126 (60.33%) - 18–79 y | Elementary and High - NA | 12,100 (32.38%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA - NA - NA |

| Zhou et al., 2021 [50] - China - 11,096 | 871 (79.5%) - 41 y | High - NA | NA | NA | 801 (73%) | NA | NA | 57 (5.2%) - NA - NA |

| Zhou, Yao, 2020 [51] - China - 751 | 257 (34.2%) - 40.02 y | Elementary and Middle - NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA - NA - NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santiago, I.S.D.; dos Santos, E.P.; da Silva, J.A.; de Sousa Cavalcante, Y.; Gonçalves Júnior, J.; de Souza Costa, A.R.; Cândido, E.L. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Teachers and Its Possible Risk Factors: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1747. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031747

Santiago ISD, dos Santos EP, da Silva JA, de Sousa Cavalcante Y, Gonçalves Júnior J, de Souza Costa AR, Cândido EL. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Teachers and Its Possible Risk Factors: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(3):1747. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031747

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantiago, Iago Sávyo Duarte, Emanuelle Pereira dos Santos, José Arinelson da Silva, Yuri de Sousa Cavalcante, Jucier Gonçalves Júnior, Angélica Rodrigues de Souza Costa, and Estelita Lima Cândido. 2023. "The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Mental Health of Teachers and Its Possible Risk Factors: A Systematic Review" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 3: 1747. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20031747