Certainty in Uncertain Times: Dental Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic–A Qualitative Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Setting

2.4. Data Collection

- Feelings of certainty due to the experiences of teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Feelings of uncertainty due to the experiences of teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2.5. Data Analysis

2.6. Ethical Approval

3. Results

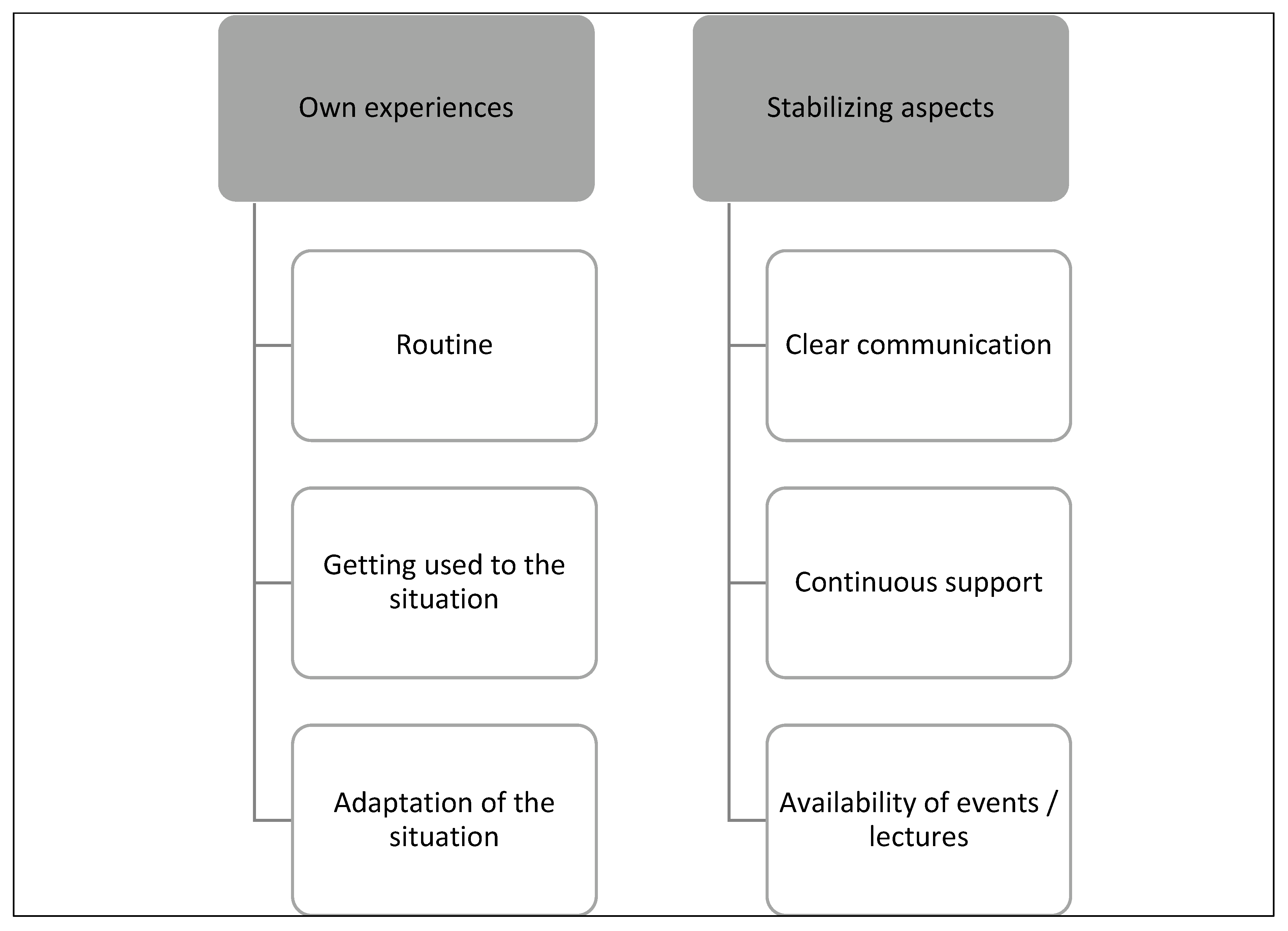

3.1. Main Topic: Certainty

3.2. Main Topic: Uncertainty

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mahase, E. China coronavirus: WHO declares international emergency as death toll exceeds 200. BMJ 2020, 368, m408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, T.Y.; Hong, G.; Paganelli, C.; Phantumvanit, P.; Chang, W.J.; Shieh, Y.S.; Hsu, M.L. Innovation of dental education during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Dent. Sci. 2021, 16, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyer, P.; Aziz, K.; Ojcius, D.M. Impact of COVID-19 on dental education in the United States. J. Dent. Educ. 2020, 84, 718–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, B.; Field, J.; Gorter, R.; Akota, I.; Manzanares, M.C.; Paganelli, C.; Davies, J.; Dixon, J.; Gabor, G.; Amaral Mendes, R.; et al. COVID-19: The immediate response of European academic dental institutions and future implications for dental education. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2020, 24, 811–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattar, S.; AlHadidi, A.; Sawair, F.A.; Alraheam, I.A.; El-Ma’aita, A.; Wahab, F.K. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on dental education: Online experience and practice expectations among dental students at the University of Jordan. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasseripour, M.; Turner, J.; Rajadurai, S.; San Diego, J.; Quinn, B.; Bartlett, A.; Volponi, A.A. COVID 19 and dental education: Transitioning from a well-established synchronous format and face to face teaching to an asynchronous format of dental clinical teaching and learning. J. Med. Educ. Curric. Dev. 2021, 8, 2382120521999667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varvara, G.; Bernardi, S.; Bianchi, S.; Sinjari, B.; Piattelli, M. Dental education challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic period in Italy: Undergraduate student feedback, future perspectives, and the needs of teaching strategies for professional development. Healthcare 2021, 9, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jum’ah, A.A.; Elsalem, L.; Loch, C.; Schwass, D.; Brunton, P.A. Perception of health and educational risks amongst dental students and educators in the era of COVID-19. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2021, 25, 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, M.; Licari, F.W.; Hon, E.S.; Lauren, E.; Su, S.; Birmingham, W.C.; Wadsworth, L.L.; Lassetter, J.H.; Graff, T.C.; Harman, W.; et al. In an era of uncertainty: Impact of COVID-19 on dental education. J. Dent. Educ. 2021, 85, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loch, C.; Kuan, I.B.J.; Elsalem, L.; Schwass, D.; Brunton, P.A.; Jum’ah, A. COVID-19 and dental clinical practice: Students and clinical staff perceptions of health risks and educational impact. J. Dent. Educ. 2021, 85, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakami, Z.; Vishwanathaiah, S.; Abuzinadah, S.H.; Alhaddad, A.J.; Bokhari, A.M.; Marghalani, H.Y.A.; Shahin, S.Y. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on the mental health of dental students: A longitudinal study. J. Dent. Educ. 2021, 85, 1854–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agius, A.M.; Gatt, G.; Vento Zahra, E.; Busuttil, A.; Gainza-Cirauqui, M.L.; Cortes, A.R.G.; Attard, N.J. Self-reported dental student stressors and experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Dent. Educ. 2021, 85, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etajuri, E.A.; Mohd, N.R.; Naimie, Z.; Ahmad, N.A. Undergraduate dental students’ perspective of online learning and their physical and mental health during COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, G.A. Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: A research note. Qual. Res. 2008, 8, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturges, J.E.; Hanrahan, K.J. Comparing telephone and face-to-face qualitative interviewing: A research note. Qual. Res. 2004, 4, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, P. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse, 11th ed.; Beltz: Weinheim, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, A.R.; Bonan, P.R.F.; Perez, D.E.C.; Martelli Júnior, H. COVID-19 pandemic and the impact on dental education: Discussing current and future perspectives. Braz. Oral Res. 2020, 34, e083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrague, L.J.; de los Santos, J.A.A.; Falguera, C.C. Social and emotional loneliness among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: The predictive role of coping behaviors, social support, and personal resilience. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2021, 57, 1578–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guse, J.; Weegen, A.S.; Heinen, I.; Bergelt, C. Mental burden and perception of the study situation among undergraduate students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study and comparison of dental and medical students. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e054728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, N. Enablers and barriers of online-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case study of an online university course. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 2021, 18, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihm, L.; Zhang, H.; van Vijfeijken, A.; Waugh, M.G. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health of university students. Int. J. Health Plan. Manag. 2021, 36, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Procentese, F.; Esposito, C.; Gonzalez Leone, F.; Agueli, B.; Arcidiacono, C.; Freda, M.F.; Di Napoli, I. Psychological lockdown experiences: Downtime or an unexpected time for being? Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 577089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Students (n = 39) | Lecturers (n = 19) |

|---|---|---|

| Women | 27 | 6 |

| Men | 12 | 13 |

| Age (Mean) (Range of ages) | 25.2 (20–31) | 44.0 (31–65) |

| Apprenticeship | 13 | - |

| Further completed study | 5 | - |

| Additional qualifications | 5 | - |

| Director of the clinic | - | 4 |

| Course instructor | - | 7 |

| Course assistant | - | 8 |

| Use of hardware *: | ||

| Laptop | 30 | 18 |

| Tablet | 10 | 0 |

| Mobile phone Stationary PC | 3 2 | 0 2 |

| Access to camera (yes) | 39 | 17 |

| Access to microphone (yes) | 38 | 17 |

| Permanent availability | 38 | 17 |

| Adequate internet connection (yes) | 38 | 19 |

| Course in home office | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goetz, K.; Wenz, H.-J.; Hertrampf, K. Certainty in Uncertain Times: Dental Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic–A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3090. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043090

Goetz K, Wenz H-J, Hertrampf K. Certainty in Uncertain Times: Dental Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic–A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2023; 20(4):3090. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043090

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoetz, Katja, Hans-Jürgen Wenz, and Katrin Hertrampf. 2023. "Certainty in Uncertain Times: Dental Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic–A Qualitative Study" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 4: 3090. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043090

APA StyleGoetz, K., Wenz, H.-J., & Hertrampf, K. (2023). Certainty in Uncertain Times: Dental Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic–A Qualitative Study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3090. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043090