Utilization of Percutaneous Mechanical Circulatory Support Devices in Cardiogenic Shock Complicating Acute Myocardial Infarction and High-Risk Percutaneous Coronary Interventions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. High-Risk Percutaneous Coronary Interventions

3. Cardiogenic Shock Complicating Acute Myocardial Infarction

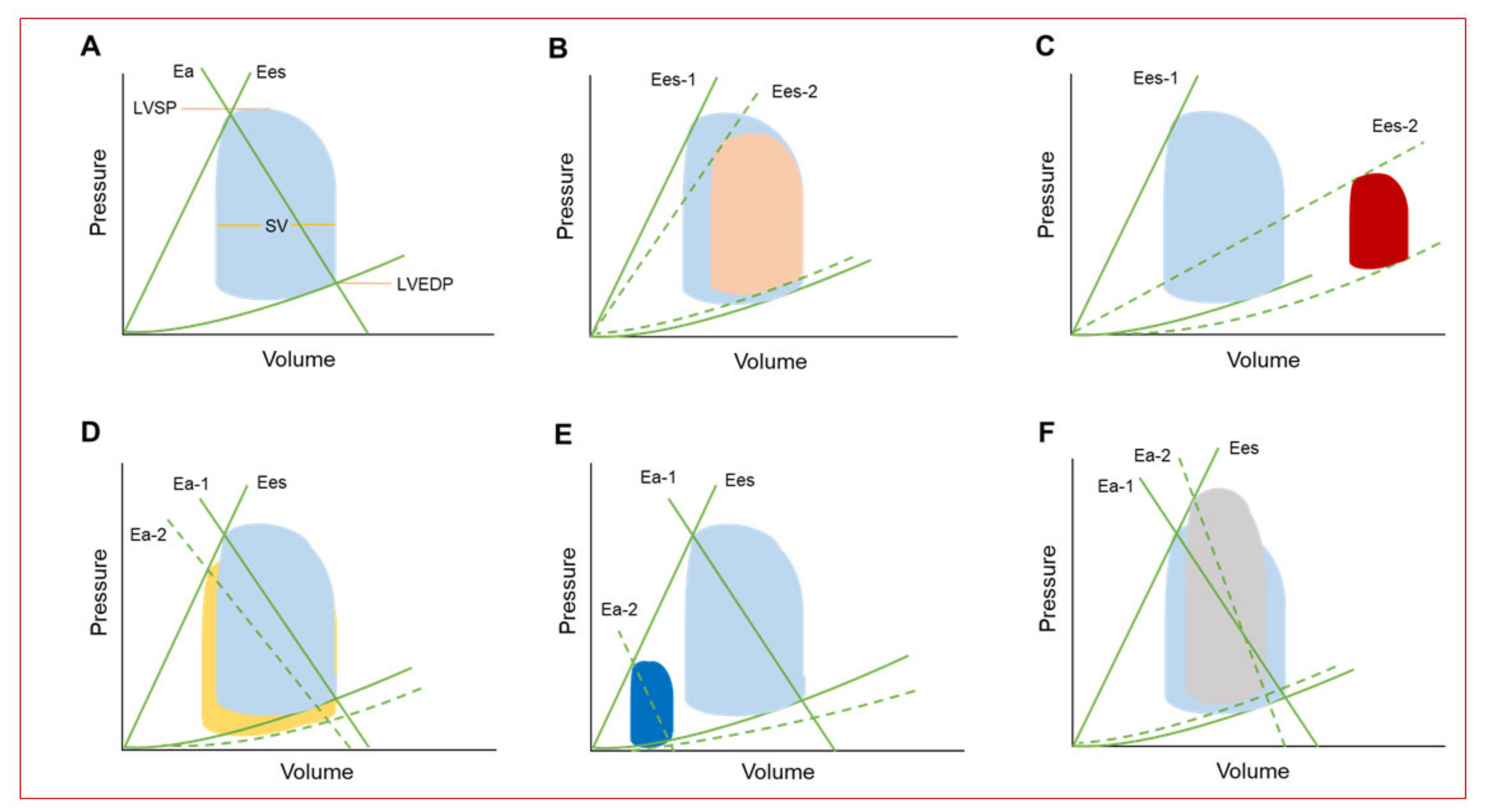

4. Hemodynamic Effects of Percutaneous Mechanical Circulatory Support Devices

5. Available Percutaneous Mechanical Circulatory Support Devices

5.1. Intraaortic Balloon Bump

5.2. Impella Devices

5.3. TandemHeart

5.4. Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (VA-ECMO)

5.5. Other Percutaneous Mechanical Support Devices

6. Clinical Benefit of Percutaneous MCS Devices for PCI

6.1. Intraaortic Balloon Bump

6.2. Impella Devices

6.3. TandemHeart

6.4. Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (VA-ECMO)

7. Recommendations for MCS Use During PCI

8. Future Directions

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Waldo, S.W.; Secemsky, E.A.; O’Brien, C.; Kennedy, K.F.; Pomerantsev, E.; Sundt, T.M., 3rd; McNulty, E.J.; Scirica, B.M.; Yeh, R.W. Surgical ineligibility and mortality among patients with unprotected left main or multivessel coronary artery disease undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation 2014, 130, 2295–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkinson, T.M.; Ohman, E.M.; O’Neill, W.W.; Rab, T.; Cigarroa, J.E. A practical approach to mechanical circulatory support in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention an interventional perspective. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2016, 9, 871–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera, D.; Stables, R.; Thomas, M.; Booth, J.; Pitt, M.; Blackman, D.; de Belder, A.; Redwood, S. BCSI-1 Investigators. Elective intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation during high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010, 304, 867–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, W.W.; Kleiman, N.S.; Moses, J.; Henriques, J.P.; Dixon, S.; Massaro, J.; Palacios, I.; Maini, B.; Mulukutla, S.; Dzavík, V. A prospective, randomized clinical trial of hemodynamic support with impella 2.5 versus intra-aortic balloon pump in patients undergoing high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention: The PROTECT II study. Circulation 2012, 126, 1717–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thiele, H.; Zeymer, U.; Neumann, F.J.; Ferenc, M.; Olbrich, H.G.; Hausleiter, J.; Richardt, G.; Hennersdorf, M.; Empen, K.; Fuernau, G. Intraaortic balloon support for myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1287–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouweneel, D.M.; Eriksen, E.; Sjauw, K.D.; van Dongen, I.M.; Hirsch, A.; Packer, E.J.; Vis, M.M.; Wykrzykowska, J.J.; Koch, K.T.; Baan, J.; et al. Percutaneous mechanical circulatory support versus intra-aortic balloon pump in cardiogenic shock after acute myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basir, M.B.; Kapur, N.K.; Patel, K.; Salam, M.A.; Schreiber, T.; Kaki, A.; Hanson, I.; Almany, S.; Timmis, S.; Dixon, S.; et al. Improved outcomes associated with the use of shock protocols: Updates from the national cardiogenic shock initiative. Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. 2019, 93, 1173–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ameloot, K.; Bastos, M.B.; Daemen, J.; Schreuder, J.; Boersma, E.; Zijlstra, F.; Van Mieghem, N.M. New generation mechanical circulatory support during high-risk PCI: A cross sectional analysis. EuroIntervention 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damluji, A.A.; Bandeen-Roche, K.; Berkower, C.; Boyd, C.M.; Al-Damluji, M.S.; Cohen, M.G.; Forman, D.E.; Chaudhary, R.; Gerstenblith, G.; Walston, J.D.; et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention in older patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 1890–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibanez, B.; James, S.; Agewall, S.; Antunes, M.J.; Bucciarelli-Ducci, C.; Bueno, H.; Caforio, A.L.P.; Crea, F.; Goudevenos, J.A.; Halvorsen, S.; et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 119–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rihal, C.S.; Naidu, S.S.; Givertz, M.M.; Szeto, W.Y.; Burke, J.A.; Kapur, N.K.; Kern, M.; Garratt, K.N.; Goldstein, J.A.; Dimas, V.; et al. 2015 SCAI/ACC/HFSA/STS clinical expert consensus statement on the use of percutaneous mechanical circulatory support devices in cardiovascular care. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 65, e7–e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levine, G.N.; Bates, E.R.; Blankenship, J.C.; Bailey, S.R.; Bittl, J.A.; Cercek, B.; Chambers, C.E.; Ellis, S.G.; Guyton, R.A.; Hollenberg, S.M.; et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI guideline for percutaneous coronary intervention. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 124, e574–e651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, T.W.; Berger, J.S.; Wang, A.; Velazquez, E.J.; Brown, DL. Impact of left ventricular dysfunction on hospital mortality among patients undergoing elective percutaneous coronary intervention. Am. J. Cardiol. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maini, B.; Naidu, S.S.; Mulukutla, S.; Kleiman, N.; Schreiber, T.; Wohns, D.; Dixon, S.; Rihal, C.; Dave, R.; O’Nell, W. Real-world use of the Impella 2.5 circulatory support system in complex high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention: The USpella registry. Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. 2012, 80, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krone, R.J.; Shaw, R.E.; Klein, L.W.; Block, P.C.; Anderson, H.V.; Weintraub, W.S.; Brindis, R.G.; McKay, C.R.; ACC-National Cardiovascular Data Registry. Evaluation of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and the Society for Coronary Angiography and Interventions lesion classification system in the current “stent era” of coronary interventions (from the ACC-National Cardiovascular. Am. J. Cardiol. 2003, 92, 389–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakakura, K.; Ako, J.; Wada, H.; Kubo, N.; Momomura, S.I. ACC/AHA classification of coronary lesions reflects medical resource use in current percutaneous coronary interventions. Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, J.M.; Curtis, J.P.; Dai, D.; Fitzgerald, S.; Khandelwal, A.K.; Spertus, J.A.; Rao, S.V.; Singh, M.; Shaw, R.E.; Ho, K.K.; et al. Enhanced mortality risk prediction with a focus on high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention: Results from 1,208,137 procedures in the NCDR (national cardiovascular data registry). JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2013, 6, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkhoff, D.; Sayer, G.; Doshi, D.; Uriel, N. Hemodynamics of mechanical circulatory support. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Diepen, S.; Katz, J.N.; Albert, N.M.; Henry, T.D.; Jacobs, A.K.; Kapur, N.K.; Kilic, A.; Menon, V.; Ohman, E.M.; Sweitzer, N.K.; et al. Contemporary management of cardiogenic shock: A scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation 2017, 136, e232–e268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, H.R.; Hochman, J.S. Cardiogenic shock current concepts and improving outcomes. Circulation 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, L. Cardiogenic shock in acute myocardial infarction the era of mechanical support. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoudi, F.A.; Ponirakis, A.; de Lemos, J.A.; Jollis, J.G.; Kremers, M.; Messenger, J.C.; Moore, J.W.M.; Moussa, I.; Oetgen, W.J.; Varosy, P.D.; et al. Trends in U.S. cardiovascular care: 2016 report from 4 ACC national cardiovascular data registries. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 69, 1427–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babaev, A.; Frederick, P.D.; Pasta, D.J.; Every, N.; Sichrovsky, T.; Hochman, J.S. Trends in management and outcomes of patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basir, M.B.; Schreiber, T.L.; Grines, C.L.; Dixon, S.R.; Moses, J.W.; Maini, B.J.; Khandelwal, A.K.; Ohman, E.M.; O’Nell, W.W. Effect of early initiation of mechanical circulatory support on survival in cardiogenic shock. Am. J. Cardiol. 2017, 119, 845–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remmelink, M.; Sjauw, K.D.; Henriques, J.P.S.; Vis, M.M.; van der Schaaf, R.J.; Koch, K.T.; Tijssen, J.G.; de Wintr, R.J.; Piek, J.J.; Baan, J., Jr. Acute left ventricular dynamic effects of primary percutaneous coronary intervention. From occlusion to reperfusion. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009, 53, 1498–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borlaug, B.A.; Kass, D.A. Invasive hemodynamic assessment in heart failure. Cardiol. Clin. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uriel, N.; Sayer, G.; Annamalai, S.; Kapur, N.K.; Burkhoff, D. Mechanical unloading in heart failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rab, T.; O’Neill, W. Mechanical circulatory support for patients with cardiogenic shock. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, H.; Ohman, E.M.; Desch, S.; Eitel, I.; De Waha, S. Management of cardiogenic shock. Eur. Heart J. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csepe, T.A.; Kilic, A. Advancements in mechanical circulatory support for patients in acute and chronic heart failure. J. Thorac. Dis. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.B. Cardiac pumping capability and prognosis in heart failure. Lancet 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C.C.; Karlin, P.; Haythe, J.; Levy, W.; Lim, T.K.; Mancini, D.M. Peak cardiac power, measured non-invasively, is a powerful predictor of mortality in chronic heart failure. Circulation 2007, 22, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- WEBER, KT. Intra-aortic balloon pumping. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaioannou, T.G.; Stefanadis, C. Basic principles of the intraaortic balloon pump and mechanisms affecting its performance. ASAIO J. 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastan, A.J.; Tillmann, E.; Subramanian, S.; Lehmkuhl, L.; Funkat, A.K.; Leontyev, S.; Doenst, T.; Walther, T.; Gutberlet, M.; Mohr, F.W. Visceral arterial compromise during intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation therapy. Circulation 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Perez, D.; Haslam, A.; Crain, T.; Gill, J.; Livingston, C.; Kaestner, V.; Hayes, M.; Morgan, D.; Cifu, A.S.; Prasad, V. A comprehensive review of randomized clinical trials in three medical journals reveals 396 medical reversals. Elife 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basra, S.S.; Loyalka, P.; Kar, B. Current status of percutaneous ventricular assist devices for cardiogenic shock. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Möbius-Winkler, S.; Fritzenwanger, M.; Pfeifer, R.; Schulze, P.C. Percutaneous support of the failing left and right ventricle—Recommendations for the use of mechanical device therapy. Heart Fail. Rev. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauten, A.; Engström, A.E.; Jung, C.; Empen, K.; Erne, P.; Cook, S.; Windecker, S.; Bergmann, M.W.; Klingenberg, R.; Lüscher, T.F.; et al. Percutaneous left-ventricular support with the impella-2.5-assist device in acute cardiogenic shock results of the impella-EUROSHOCK-registry. Circ. Hear Fail. 2013, 6, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remmelink, M.; Sjauw, K.D.; Henriques, J.P.; De Winter, R.J.; Vis, M.M.; Koch, K.T.; Paulus, W.J.; De Mol, B.A.; Tijssen, J.G.; Piek, J.J.; et al. Effects of mechanical left ventricular unloading by impella on left ventricular dynamics in high-risk and primary percutaneous coronary intervention patients. Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi, R.; Patel, K.; Decter, D.; Gupta, R.; Meraj, P. Trends in the utilisation and in-hospital mortality associated with short-term mechanical circulatory support for heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Hear Lung Circ. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, C.A.; Singh, V.; Londoño, J.C.; Cohen, M.G.; Alfonso, C.E.; O’Neill, W.W.; Heldman, A.W. Percutaneous retrograde left ventricular assist support for patients with aortic stenosis and left ventricular dysfunction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 80, 1201–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kar, B.; Gregoric, I.D.; Basra, S.S.; Idelchik, G.M.; Loyalka, P. The percutaneous ventricular assist device in severe refractory cardiogenic shock. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkhoff, D.; Naidu, S.S. The science behind percutaneous hemodynamic support: A review and comparison of support strategies. Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kono, S.; Nishimura, K.; Nishina, T.; Komeda, M.; Akamatsu, T. Auto-synchronized systolic unloading during left ventricular assist with centrifugal pump. ASAIO J. 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.T.; Al-Quthami, A.; Kapur, N.K. Percutaneous left ventricular support in cardiogenic shock and severe aortic regurgitation. Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouweneel, D.M.; Schotborgh, J.V.; Limpens, J.; Sjauw, K.D.; Engström, A.E.; Lagrand, W.K.; Cherpanath, T.G.V.; Driessen, A.H.G.; De Mol, B.A.J.M.; Henriques, J.P.S. Extracorporeal life support during cardiac arrest and cardiogenic shock: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiagarajan, R.R.; Barbaro, R.P.; Rycus, P.T.; McMullan, D.M.; Conrad, S.A.; Fortenberry, J.D.; Paden, M.L. Extracorporeal life support organization registry international report 2016. ASAIO J. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghili, N.; Kang, S.; Kapur, N.K. The fundamentals of extra-corporeal membrane oxygenation. Minerva Cardioangiol. 2015, 63, 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- MacLaren, G.; Combes, A.; Bartlett, R.H. Contemporary extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for adult respiratory failure: Life support in the new era. Intensive Care Med. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, J.J.; Aleksova, N.; Pitcher, I.; Couture, E.; Parlow, S.; Faraz, M.; Visintini, S.; Simard, T.; Di Santo, P.; Mathew, R.; et al. Left ventricular unloading during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in patients with cardiogenic shock. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koeckert, M.S.; Jorde, U.P.; Naka, Y.; Moses, J.W.; Takayama, H. Impella LP 2.5 for left ventricular unloading during venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. J. Cardiol. Surg. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostadal, P.; Mlcek, M.; Gorhan, H.; Simundic, I.; Strunina, S.; Hrachovina, M.; Krüger, A.; Vondrakova, D.; Janotka, M.; Hala, P.; et al. Electrocardiogram-synchronized pulsatile extracorporeal life support preserves left ventricular function and coronary flow in a porcine model of cardiogenic shock. PLoS ONE 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Izer, J.M.; Clark, J.B.; Patel, S.; Pauliks, L.; Kunselman, A.R.; Leach, D.; Cooper, T.K.; Wilson, R.P.; Ündar, A. In vivo hemodynamic performance evaluation of novel electrocardiogram-synchronized pulsatile and nonpulsatile extracorporeal life support systems in an adult swine model. Artif. Organs 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, R.; Strother, A.; Wang, S.; Kunselman, A.R.; Ündar, A. Impact of pulsatility and flow rates on hemodynamic energy transmission in an adult extracorporeal life support system. Artif. Organs 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöss, J.; Kriechbaum, S.; Ewen, S.; Graf, J.; Hager, I.; Hennersdorf, M.; Petros, S.; Link, A.; Bohm, M.; Thiele, H.; et al. First-in-man analysis of the i-cor assist device in patients with cardiogenic shock. Eur. Heart J. Acute Cardiovasc. Care 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masyuk, M.; Abel, P.; Hug, M.; Wernly, B.; Haneya, A.; Sack, S.; Sideris, K.; Langwieser, N.; Graf, T.; Fuernau, G.; et al. Real-world clinical experience with the percutaneous extracorporeal life support system: Results from the German Lifebridge® Registry. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.; Hachamovitch, R.; Kittleson, M.; Patel, J.; Arabia, F.; Moriguchi, J.; Esmailian, F.; Azarbal, B. Complications of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for treatment of cardiogenic shock and cardiac arrest: A meta-analysis of 1,866 adult patients. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uil, C.D.; Daemen, J.; Lenzen, M.; Maugenest, A.-M.; Joziasse, L.; Van Geuns, R.; Van Mieghem, N. Pulsatile iVAC 2L circulatory support in high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention. EuroIntervention 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, V.V.; Archer, S.L.; Badesch, D.B.; Barst, R.J.; Farber, H.W.; Lindner, J.R.; Mathier, M.A.; McGoon, M.D.; Park, M.H.; Rosenson, R.S.; et al. ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation task force on expert consensus documents and the American Heart Association Developed in Collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians; American Thoracic Society, Inc.; and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, M.B.; Goldstein, J.; Milano, C.; Morris, L.D.; Kormos, R.L.; Bhama, J.; Kapur, N.K.; Bansal, A.; Garcia, J.; Baker, J.N.; et al. Benefits of a novel percutaneous ventricular assist device for right heart failure: The prospective RECOVER RIGHT study of the Impella RP device. J. Heart Lung Transplant. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, S.; Tepper, D.; Ip, R. Comparison of hospital mortality with intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation insertion before vs after primary percutaneous coronary intervention for cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. Congest. Heart Fail. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjauw, K.D.; Engström, A.E.; Vis, M.M.; van der Schaaf, R.J.; Baan, J., Jr.; Koch, K.T.; de Winter, R.J.; Piek, J.J.; Tijssen, J.G.; Henriques, J.P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of intra-aortic balloon pump therapy in ST-elevation myocardial infarction: Should we change the guidelines? Eur. Heart J. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochman, J.S.; Sleeper, L.A.; Webb, J.G.; Sanborn, T.A.; White, H.D.; Talley, J.D.; Buller, C.E.; Jacobs, A.K.; Slater, J.N.; Col, J.; et al. Early revascularization in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. SHOCK Investigators. Should we emergently revascularize occluded coronaries for cardiogenic shock. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, H.; Zeymer, U.; Neumann, F.-J.; Ferenc, M.; Olbrich, H.-G.; Hausleiter, J.; De Waha, A.; Richardt, G.; Hennersdorf, M.; Empen, K.; et al. Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock (IABP-SHOCK II): Final 12 month results of a randomised, open-label trial. Lancet 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, H.; Zeymer, U.; Thelemann, N.; Neumann, F.J.; Hausleiter, J.; Abdel-Wahab, M.; Meyer-Saraei, R.; Fuernau, G.; Eitel, I.; Hambrecht, R.; et al. Intraaortic balloon pump in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction: Long-term 6-year outcome of the randomized IABP-SHOCK II trial. Circulation 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehmer, G.J.; Blankenship, J.C.; Cilingiroglu, M.; Dwyer, J.G.; Feldman, D.N.; Gardner, T.J.; Grines, C.L.; Singh, M. SCAI/ACC/AHA Expert consensus document: 2014 update on percutaneous coronary intervention without on-site surgical backup. Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.R.; Smalling, R.W.; Thiele, H.; Barnhart, H.X.; Zhou, Y.; Chandra, P.; Chew, D.; Choen, M.; French, J.; Perera, D.; et al. Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation and infarct size in patients with acute anterior myocardial infarction without shock: The CRISP AMI randomized trial. JAMA-J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, J.P.; Rathore, S.S.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Nallamothu, B.K.; Krumholz, H.M. Use and effectiveness of intra-Aortic balloon pumps among patients undergoing high risk percutaneous coronary intervention: Insights from the national cardiovascular data registry. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, D.; Stables, R.; Clayton, T.; De Silva, K.; Lumley, M.; Clack, L.; Thomas, M.; Redwood, S.; BCSI-1 Investigators. Long-term mortality data from the balloon pump–assisted coronary intervention study (BCIS-1). Circulation 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Gara, P.T.; Kushner, F.G.; Ascheim, D.D.; E Casey, D.; Chung, M.K.; A De Lemos, J.; Ettinger, S.M.; Fang, J.C.; Fesmire, F.M.; A Franklin, B.; et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of st-elevation myocardial infarction: Executive summary: A report of the American college of cardiology foundation/american heart association task force on practice guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfarth, M.; Sibbing, D.; Bauer, I.; Fröhlich, G.; Bott-Flügel, L.; Byrne, R.; Dirschinger, J.; Kastrati, A.; Schömig, A. A Randomized clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of a percutaneous left ventricular assist device versus intra-aortic balloon pumping for treatment of cardiogenic shock caused by myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeymer, U.; Thiele, H. Mechanical support for cardiogenic shock: Lost in translation? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatolios, K.; Chatzis, G.; Markus, B.; Luesebrink, U.; Ahrens, H.; Dersch, W.; Betz, S.; Ploeger, B.; Boesl, E.; O’Neill, W.; et al. Impella support compared to medical treatment for post-cardiac arrest shock after out of hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrage, B.; Ibrahim, K.; Loehn, T.; Werner, N.; Sinning, J.-M.; Pappalardo, F.; Pieri, M.; Skurk, C.; Lauten, A.; Landmesser, U.; et al. Impella support for acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. Circulation 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernly, B.; Seelmaier, C.; Leistner, D.; Stähli, B.E.; Pretsch, I.; Lichtenauer, M.; Jung, C.; Hoppe, U.C.; Landmesser, U.; Thiele, H.; et al. Mechanical circulatory support with Impella versus intra-aortic balloon pump or medical treatment in cardiogenic shock—A critical appraisal of current data. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriques, J.P.; Remmelink, M.; Baan, J.; Van Der Schaaf, R.J.; Vis, M.M.; Koch, K.T.; Scholten, E.W.; De Mol, B.A.; Tijssen, J.G.; Piek, J.J.; et al. Safety and feasibility of elective high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention procedures with left ventricular support of the impella recover LP 2.5. Am. J. Cardiol. 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.R.; Henriques, J.P.; Mauri, L.; Sjauw, K.; Civitello, A.; Kar, B.; Loyalka, P.; Resnic, F.S.; Teirstein, P.; Makkar, R.; et al. A prospective feasibility trial investigating the use of the impella 2.5 system in patients undergoing high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention (The PROTECT I Trial). Initial U.S. Experience. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangas, G.D.; Kini, A.S.; Sharma, S.K.; Henriques, J.P.; Claessen, B.E.; Dixon, S.R.; Massaro, J.M.; Palacios, I.; Popma, J.J.; Ohman, E.M.; et al. Impact of hemodynamic support with impella 2.5 versus intra-aortic balloon pump on prognostically important clinical outcomes in patients undergoing high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention (from the PROTECT II randomized trial). Am. J. Cardiol. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, H.; Sick, P.; Boudriot, E.; Diederich, K.-W.; Hambrecht, R.; Niebauer, J.; Schuler, G. Randomized comparison of intra-aortic balloon support with a percutaneous left ventricular assist device in patients with revascularized acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. Eur. Heart J. 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhoff, D.; Cohen, H.; Brunckhorst, C.; O’Neill, W.W. A randomized multicenter clinical study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the TandemHeart percutaneous ventricular assist device versus conventional therapy with intraaortic balloon pumping for treatment of cardiogenic shock. Am. Heart J. 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alli, O.O.; Singh, I.M.; Holmes, D.R.; Pulido, J.N.; Park, S.J.; Rihal, C.S. Percutaneous left ventricular assist device with TandemHeart for high-risk percutaneous coronary intervention: The Mayo Clinic experience. Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briasoulis, A.; Telila, T.; Palla, M.; Mercado, N.; Kondur, A.; Grines, C.; Schreiber, T. Meta-analysis of usefulness of percutaneous left ventricular assist devices for high-risk percutaneous coronary interventions. Am. J. Cardiol. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermudez, C.; Kormos, R.; Subramaniam, K.; Mulukutla, S.; Sappington, P.; Waters, J.; Khandhar, S.J.; Esper, S.A.; Dueweke, E.J. Extracorporeal Membrane oxygenation support in acute coronary syndromes complicated by cardiogenic shock. Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, S.I.; Sokolovic, M.; Koifman, E.; Kiramijyan, S.; Torguson, R.; Lindsay, J.; Ben-Dor, I.; Suddath, W.; Pichard, A.; Satler, L.; et al. Contemporary use of veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for refractory cardiogenic shock in acute coronary syndrome. J. Invasive Cardiol. 2016, 28, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.-S.; Chao, A.; Yu, H.-Y.; Ko, W.-J.; Wu, I.-H.; Chen, R.J.-C.; Huang, S.-C.; Lin, F.-Y.; Wang, S.-S. Analysis and results of prolonged resuscitation in cardiac arrest patients rescued by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrage, B.; Burkhoff, D.; Rübsamen, N.; Becher, P.M.; Schwarzl, M.; Bernhardt, A.; Grahn, H.; Lubos, E.; Söffker, G.; Clemmensen, P.; et al. Unloading of the left ventricle during venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy in cardiogenic shock. JACC Heart Fail. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myat, A.; Patel, N.; Tehrani, S.; Banning, A.P.; Redwood, S.R.; Bhatt, D.L. Percutaneous circulatory assist devices for high-risk coronary intervention. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maini, B.; Gregory, D.; Scotti, D.J.; Buyantseva, L. Percutaneous cardiac assist devices compared with surgical hemodynamic support alternatives: Cost-effectiveness in the emergent setting. Catheter Cardiovasc. Interv. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, J.B.; Doshi, S.N.; Konorza, T.; Palacios, I.; Schreiber, T.; Borisenko, O.V.; Henriques, J.P.S. The cost-effectiveness of a new percutaneous ventricular assist device for high-risk PCI patients: mid-stage evaluation from the European perspective. J. Med. Econ. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udesen, N.J.; Møller, J.E.; Lindholm, M.G.; Eiskjær, H.; Schäfer, A.; Werner, N.; Holmvang, L.; Terkelsen, C.J.; Jensen, L.O.; Junker, A.; et al. Rationale and design of DanGer shock: Danish-German cardiogenic shock trial. Am. Heart J. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, C.; Bueter, S.; Wernly, B.; Masyuk, M.; Saeed, D.; Albert, A.; Fuernau, G.; Kelm, M.; Westenfeld, R. Lactate clearance predicts good neurological outcomes in cardiac arrest patients treated with extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation. J. Clin. Med. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slottosch, I.; Liakopoulos, O.; Kuhn, E.; Scherner, M.; Deppe, A.-C.; Sabashnikov, A.; Mader, N.; Choi, Y.-H.; Wippermann, J.; Wahlers, T. Lactate and lactate clearance as valuable tool to evaluate ECMO therapy in cardiogenic shock. J. Crit. Care 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fux, T.; Holm, M.; Corbascio, M.; van der Linden, J. cardiac arrest prior to venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit. Care Med. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-C.; Fang, C.-Y.; Chen, H.-C.; Chen, C.-J.; Yang, C.-H.; Hang, C.-L.; Yip, H.-K.; Fang, H.-Y.; Wu, C.-J. Associations with 30-day survival following extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in patients with acute ST segment elevation myocardial infarction and profound cardiogenic shock. Heart Lung J. Acute Crit. Care 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, N.K.; Paruchuri, V.; Urbano-Morales, J.A.; Mackey, E.E.; Daly, G.H.; Qiao, X.; Pandian, N.; Perides, G.; Karas, R.H. Mechanically unloading the left ventricle before coronary reperfusion reduces left ventricular wall stress and myocardial infarct size. Circulation 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.L.; Zhang, Y.; Qiao, X.; Reyelt, L.; Paruchuri, V.; Schnitzler, G.R.; Morine, K.J.; Annamalai, S.K.; Bogins, C.; Natov, P.S.; et al. Left ventricular unloading before reperfusion promotes functional recovery after acute myocardial infarction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyns, B.; Stolinski, J.; Leunens, V.; Verbeken, E.; Flameng, W. Left ventricular support by catheter-mounted axial flow pump reduces infarct size. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2003, 41, 1087–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, N.K.; Qiao, X.; Paruchuri, V.; Morine, K.J.; Syed, W.; Dow, S.; Shah, N.; Pandian, N.; Karas, R.H. Mechanical pre-conditioning with acute circulatory support before reperfusion limits infarct size in acute myocardial infarction. JACC Heart Fail. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapur, N.K.; Alkhouli, M.A.; DeMartini, T.J.; Faraz, H.; George, Z.H.; Goodwin, M.J.; Hernandez-Montfort, J.A.; Iyer, V.S.; Josephy, N.; Kalra, S.; et al. Unloading the left ventricle before reperfusion in patients with anterior st-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: A pilot study using the impella CP. Circulation 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, W.W.; Grines, C.; Schreiber, T.; Moses, J.; Maini, B.; Dixon, S.R.; Ohman, E.M.; O’Neill, W.W. Analysis of outcomes for 15,259 US patients with acute myocardial infarction cardiogenic shock (AMICS) supported with the Impella device. Am. Heart J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, M.P.; Khan, A.R.; O’Neill, W.W. Early initiation of impella in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock improves survival: A meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auffret, V.; Cottin, Y.; Leurent, G.; Gilard, M.; Beer, J.-C.; Zabalawi, A.; Chagué, F.; Filippi, E.; Brunet, D.; Hacot, J.-P.; et al. Predicting the development of in-hospital cardiogenic shock in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary percutaneous coronary intervention: The ORBI risk score. Eur. Heart J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrage, B.; Westermann, D. Reply: Does VA-ECMO plus impella work in refractory cardiogenic shock? JACC Heatr Fail. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yan, S.; Gao, S.; Liu, M.; Lou, S.; Liu, G.; Ji, B.; Gao, B. Effect of an intra-aortic balloon pump with venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation on mortality of patients with cardiogenic shock: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cardio-Thoracic Surg. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohman, E.M.; Nanas, J.; Stomel, R.J.; Leesar, M.A.; Nielsen, D.W.T.; O’Dea, D.; Rogers, F.J.; Harber, D.; Hudson, M.P.; Fraulo, E.; et al. Thrombolysis and counterpulsation to improve survival in myocardial infarction complicated by hypotension and suspected cardiogenic shock or heart failure: Results of the TACTICS trial. J. Thromb. Thrombolysis 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waksman, R.; Weiss, A.T.; Gotsman, M.S.; Hasin, Y. Intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation improves survival in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction. Eur. Heart J. 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, H.V.; Every, N.R.; Parsons, L.S.; Angeja, B.; Goldberg, R.J.; Gore, J.M.; Chou, T.M. The use of intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation in patients with cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction: Data from the national registry of myocardial infarction 2. Am. Heart J. 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.M.; Uil, C.A.D.; Hoeks, S.E.; Van Der Ent, M.; Jewbali, L.S.; Van Domburg, R.T.; Serruys, P.W. Percutaneous left ventricular assist devices vs. intra-aortic balloon pump counterpulsation for treatment of cardiogenic shock: A meta-analysis of controlled trials. Eur. Heart J. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alushi, B.; Douedari, A.; Froehlich, G.; Knie, W.; Leistner, D.; Staehli, B.; Mochmann, H.-C.; Pieske, B.; Landmesser, U.; Krackhardt, F.; et al. P2481Impella assist device or intraaortic balloon pump for treatment of cardiogenic shock due to acute coronary syndrome. Eur. Heart J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichol, G.; Karmy-Jones, R.; Salerno, C.; Cantore, L.; Becker, L. Systematic review of percutaneous cardiopulmonary bypass for cardiac arrest or cardiogenic shock states. Resuscitation 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, J.-J.; Tsai, T.-H.; Lee, F.-Y.; Fang, H.-Y.; Sun, C.-K.; Leu, S.; Yang, C.-H.; Chen, S.-M.; Hang, C.-L.; Hsieh, Y.-K.; et al. Early extracorporeal membrane oxygenator-assisted primary percutaneous coronary intervention improved 30-day clinical outcomes in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction complicated with profound cardiogenic shock. Crit. Care Med. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, H.; Truby, L.; Koekort, M.; Uriel, N.; Colombo, P.; Mancini, D.M.; Jorde, U.P.; Naka, Y. Clinical outcome of mechanical circulatory support for refractory cardiogenic shock in the current era. J. Heart Lung Transplant 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teirstein, P.S.; Vogel, R.A.; Dorros, G.; Stertzer, S.H.; Vandormael, M.; Smith, S.C.; Overlie, P.A.; O’Neill, W.W. Prophylactic versus standby cardiopulmonary support for high risk percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, T.L.; Kodali, U.R.; O’Neill, W.W.; Gangadharan, V.; Puchrowicz-Ochocki, S.B.; Grines, C.L. Comparison of acute results of prophylactic intraaortic balloon pumping with cardiopulmonary support for percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA). Catheter Cardiovasc. Diagn. 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patient Characteristics |

| Increased age |

| Comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, chronic lung disease, prior myocardial infarction, peripheral arterial disease, frailty) |

| Severe LV systolic dysfunction (EF < 20–30%) |

| Severe renal function impairment (eGFR < 30 mL/min/1.73 m2). |

| Lesion Characteristics |

| Severe three-vessel coronary artery disease |

| Unprotected left main stenosis |

| Bifurcation disease or ostial stenosis |

| High SYNTAX score or type C lesions |

| Chronic total occlusions |

| Saphenous vein graft disease |

| Heavily calcified lesions requiring coronary atherectomy |

| Clinical Presentation |

| Acute coronary syndrome |

| Heart failure symptoms (dyspnea, orthopnea, PND, exercise intolerance, peripheral edema) |

| Arrhythmias (atrial fibrillation with RVR, ventricular tachycardia) |

| Elevated LV end-diastolic pressure |

| Severe mitral regurgitation (or other valvular disease) |

| Features | IABP | Impella 2.5 | Impella CP | iVAC 2L | TandemHeart | VA-ECMO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflow/outflow | Aorta | LV→aorta | LV→aorta | LV→aorta | LA→aorta | RA→aorta |

| Mechanism of action | Pneumatic | Axial flow | Axial flow | Pulsatile flow | Centrifugal flow | Centrifugal flow |

| Insertion approach | Pc (FA) | Pc (FA) | Pc (FA) | Pc (FA) | Pc (FA/FV) | Pc (FA/FV) |

| Sheath size | 7–8 F | 13 F | 14 F | 17 F | Venous: 21 F Arterial: 12–19 F | Venous: 17–21 F Arterial: 16–19 F |

| Flow (L/min) | 0.3–0.5 | Max 2.5 | 3.7–4.0 | Max 2.8 | Max 4.0 | Max 7.0 |

| Pump speed (RPM) | N/A | Max 51,000 | Max 51,000 | 40 mL/beat | Max 7500 | Max 5000 |

| Duration of support | 2–5 days | 6 h–10 days | 6 h–10 days | 6 h–10 days | UP to 14 days | 7–10 days |

| LV function dependency | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Synchrony with the cardiac cycle | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| LV unloading | + | ++ | +++ | + | +++ | − |

| Afterload | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑↑ |

| MAP | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↑↑ | ↑↑ | ↑↑ | ↑↑ |

| Cardiac index | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↑↑↑ | ↑↑ | ↑↑↑ | ↑↑↑ |

| PCWP | ↓ | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↔ |

| LVEDP | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓↓ | ↔ |

| Coronary perfusion | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↔ | ↔ |

| Myocardial oxygen demand | ↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↓ | ↓↔ | ↔ |

| Anticoagulation | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Implant complexity | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | ++ |

| Management complexity | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| Complications | Limb ischemia, bleeding | Hemolysis, limb ischemia, bleeding | Hemolysis, limb ischemia, bleeding | Hemolysis, limb ischemia, bleeding | Limb ischemia, bleeding, hemolysis | Bleeding, limb ischemia, hemolysis |

| Contraindications | Moderate-to-severe AR, severe PAD | Severe AS/AR, mechanical AoV, LV thrombus, CI to AC | Severe AS/AR, mechanical AoV, LV thrombus, CI to AC | Severe AS/AR, mechanical AoV, LV thrombus, CI to AC | Moderate-to-severe AR, severe PAD, CI to AC, LA thrombus | Moderate-to-severe AR, severe PAD, CI to AC |

| CE-certification | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| FDA approval | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| First Author/Study (Ref. #) | N | Study Type | Study Arms | Definition | Primary Endpoint | Salient Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IABP | ||||||

| IABP-SHOCK-II [5,65,66] | 600 | RCT | IABP versus no IABP | AMI with cardiogenic shock (SBP < 90 mmHg for >30 min or need for vasoactive agents, pulmonary congestion, impaired organ perfusion) | 30-day, 1-year, 6-year all-cause mortality | No difference in survival at 30 days [5], 1 year [65], and 6 years [66]. No differences recurrent MI, stroke, ischemic comp, severe bleeding, or sepsis. |

| TACTICs [106] | 57 | RCT | Fibrinolytic therapy with IABP versus without IABP | AMI with sustained hypotension and heart failure with signs of hypoperfusion | 6-month all-cause Mortality | No survival benefit except for patients with Killip III/IV supported with IABP. |

| Waksman et al. [107] | 45 | Prospective, nonrandomized | Fibrinolytic therapy with IABP versus without IABP | AMI complicated by cardiogenic shock | In-hospital and 1-year all-cause mortality | In-hospital and 1-year survival improved with IABP after early revascularization with fibrinolytic therapy. |

| NRMI [108] | 23,180 | Observational | Fibrinolytic or PCI with IABP versus no IABP | AMI with cardiogenic shock at initial presentation or during hospitalization | In-hospital all-cause mortality | IABP was associated with decreased in-hospital mortality in patients received fibrinolysis but not PCI. |

| Hariss et al. [62] | 48 | Observational | IABP prior to PCI versus late IABP | AMI complicated by cardiogenic shock | In-hospital all-cause mortality | Early IABP was associated with decreased in-hospital mortality compared with late IABP. |

| Sjauw et al. [63] | 1009 (RCTs) 10,529 (cohort studies) | Meta-analysis (7 RCTs, 9 cohort studies) | IABP versus no IABP | AMI complicated by cardiogenic shock | 30-day all-cause mortality | No survival benefit or improvement in LV ejection fraction with IABP. |

| Impella | ||||||

| ISAR-SHOCK [72] | 25 | RCT | Impella 2.5 versus IABP | AMI complicated by cardiogenic shock | Change in the CI at 30 min post implantation | Superior hemodynamics with Impella. Mortality was similar between the two groups. |

| EUROSHOCK [39] | 120 | Observational | Impella 2.5 | AMI complicated by cardiogenic shock | 30-day all-cause mortality | 30-day mortality was high at 64% despite improvement in hemodynamic and metabolic parameters with Impella. |

| IMPRESS in Severe Shock [6] | 48 | RCT | Impella CP versus IABP | AMI with severe shock (SBP < 90 mmHg or the need for vasoactive agents, and all required mechanical ventilation) | 30-day all-cause mortality | Mortality occurred in 50% of patients with no significant survival benefit with Impella. |

| Karatolios et al. [74] | 90 | Observational | Impella versus medical therapy | AMI with post-cardiac arrest cardiogenic shock | In-hospital all-cause mortality | Impella group had better survival at discharge and after 6 months despite being a sicker group. |

| Schrage et al. [75] | 237 | Observational | Impella 2.5 (~30%), Impella CP (~70%) versus IABP (matched from IABP-SHOCK trial) | AMI with cardiogenic shock (SBP < 90 mmHg for >30 min or need for vasoactive agents, pulmonary congestion, impaired organ perfusion) | 30-day all-cause mortality | Impella was not associated with lower 30-day mortality. Severe bleedings and peripheral vascular complications were more common with Impella use. |

| Wernly et al. [76] | 588 | Meta-analysis (4 studies) | Impella versus IABP or medical therapy alone | AMI with cardiogenic shock | 30-day all-cause mortality | No improvement in short-term survival with Impella. Higher risk of major bleeding and peripheral ischemic events with Impella. |

| Cheng et al. [109] | 100 | Meta-analysis (3 RCTs; 1 for Impella versus IABP and 2 for TandemHeart versus IABP)) | Impella or TandemHeart versus IABP | AMI with cardiogenic shock | 30-day all-cause mortality | No significant differences in 30-day mortality. Improved hemodynamics with Impella and TandemHeart. Higher rates of bleeding with TandemHeart and of hemolysis with Impella. |

| Alushi et al. [110] | 116 | Observational | Impella 2.5 (~30%), Impella CP (~70%) versus IABP | AMI with cardiogenic shock | 30-day all-cause mortality | No significant differences in 30-day mortality. Impella significantly reduced the inotropic score, lactate levels, and improved LVEF compared with IABP. Higher rates of bleeding with Impella. |

| TandemHeart | ||||||

| Kar et al. [43] | 117 | Observational | TandemHeart | Severe cardiogenic shock despite vasopressor and IABP support | 30-day all-cause mortality | 30-day mortality: 40%. Improvement in hemodynamics refractory to vasopressors and IABP. |

| Thiele et al. [80] | 41 | RCT | TandemHeart versus IABP | AMI with cardiogenic shock (CI < 2.1 L/min/m2, lactate > 2) | Change in cardiac index | Hemodynamic and metabolic parameters were reversed more effectively by TandemHeart. 30-day mortality was similar. Bleeding and ischemic events were more common with TandemHeart. |

| Burkhoff et al. [81] | 42 | RCT | TandemHeart versus IABP | Severe cardiogenic shock (most had AMI and failed IABP) | 30-day all-cause mortality | Similar mortality rates and adverse events at 30 days. Superior hemodynamics with TandemHeart. |

| VA-ECMO | ||||||

| Esper et al. [84] | 18 | Observational | VA-ECMO | Severe cardiogenic shock due to ACS | Survival to hospital discharge | Survival rates at discharge: 67%. High bleeding rates (94% required blood transfusion). |

| Negi et al. [85] | 15 | Observational | VA-ECMO | AMI with severe cardiogenic shock (60% had STEMI and IABP support) | Survival to hospital discharge | Survival rates at discharge: 47%. Vascular complications: 53%. |

| Nichol et al. [111] | 1494 (84 studies) | Systematic review | VA-ECMO | Cardiogenic shock or cardiac arrest | Survival to hospital discharge | Survival to hospital discharge: 50%. |

| Sheu et al. [112] | Group 1: 115 Group 2: 219 | Observational | Group 1: profound shock without ECMO versus group 2: profound shock with ECMO | AMI and profound cardiogenic shock (SBP < 75 mmHg despite IABP and vasopressor support) | 30-day survival | ECMO group had higher survival rates: 60.9% versus 28% in non-ECMO group. |

| Takayama et al. [113] | 90 | Observational | VA-ECMO | Refractory cardiac shock (AMI in 49%) | Survival to hospital discharge | Survival to hospital discharge: 49%. Bleeding and stroke rates: 26%; and LV distension and pulmonary edema: 18%. |

| First Author/Study (Ref. #) | N | Study Type | Study Arms | Definition | Primary Endpoint | Salient Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IABP | ||||||

| BCIS-1 [3] | 301 | RCT | Elective IABP versus no IABP before PCI | High-risk PCI without cardiogenic shock, LVEF < 30%, severe CAD (jeopardy score > 8) | MACE: Composite of death, AMI, stroke, revascularization at hospital discharge | No reduction in MACE. No difference in survival rates at 6 months. Decreased major procedural complications with planned IABP (mainly hypotension). |

| Extended BCIS-1 [70] | 301 | RCT | Elective IABP versus no IABP before PCI | High-risk PCI without cardiogenic shock, LVEF < 30%, severe CAD (jeopardy score > 8) | Long-term All-cause mortality | Elective IABP use was associated with a 34% relative reduction in all-cause mortality at 4 years post PCI. |

| CRISP-AMI [68] | 337 | RCT | Elective IABP prior to PCI until at least 12 h post versus no IABP | Acute anterior MI without cardiogenic shock | Infarct size measured by cardiac MRI at 3–5 days post PCI | No reduction in infarct size with IABP use. Survival at 6 months and procedural complications were similar between groups. |

| NCDR [69] | 181,599 | Observational | Elective IABP versus no IABP before PCI | LVEF < 30%, severe CAD, including patients with cardiogenic shock | In-hospital mortality | IABP use varied significantly across hospitals. No association with differences in in-hospital mortality. |

| Impella | ||||||

| Henriques et al. [77] | 19 | Observational | Impella 2.5 | High-risk PCI (elderly, most with prior MI, poor surgical candidates, LVEF < 40%) | Safety and feasibility of Impella use | A 100% procedural success and no important device-related adverse events. |

| PROTECT I [78] | 20 | Prospective, nonrandomized | Impella 2.5 | High-risk PCI (LVEF < 35%, UPLM disease or last patent vessel) | Safety and feasibility of Impella use | Impella is safe, easy to implant, and provides excellent hemodynamic support during high-risk PCI. |

| USPella [14] | 175 | Observational | Impella 2.5 | High-risk PCI (severe three-vessel disease or UPLM, mean SYNTAX score 36, low LVEF) | MACE at 30 days | MACE: 8%. 30-day, 6-month, and 12-month survival: 96%, 91%, and 88%, respectively. |

| PROTECT II [4] | 452 | RCT | Impella 2.5 versus IABP | High-risk PCI (LVEF < 35%, UPLM, three-vessel or last patent vessel disease) | MACE (a composite of 11 adverse events) at 30 days | 30-day MACE was similar between groups (ITT) and trend for lower MACE with Impella (PP). 90-day MACE was similar (ITT) and significantly lower with Impella (PP). |

| Ameelot et al. [8] | 198 | Observational | Impella CP, heartmate PHP, or PulseCath iVAC2L versus unprotected PCI | Prophylactic high-risk PCI | A composite of procedure-related adverse events | Lower rates of periprocedural adverse events with Impella devices. 30-day survival was significantly higher with Impella versus unsupported PCI. |

| TandemHeart | ||||||

| Alli et al. [82] | 54 | Observational | TandemHeart | Prophylactic high-risk PCI (STS score 13%, SYNTAX score 33, three-vessel and UPLM disease) | 6-month survival | 6-month survival: 87%. Major vascular complications: 13%. |

| Briasoulis et al. [83] | 205 | Meta-analysis (8 cohort studies) | TandemHeart | Prophylactic high-risk PCI | 30-day all-cause mortality | 30-day mortality: 8%. Major bleeding rates: 3.6%. |

| VA-ECMO | ||||||

| Teirstein et al. [114] | 389 (prophylactic support) 180 (standby support) | Observational | VA-ECMO | High-risk PCI (LVEF < 25%, culprit lesion supplying > 50% of the myocardium) | PCI success rates and major complications rates | Comparable results in the prophylactic compared with the standby VA-ECMO support groups. Patients with extremely low LVEF may benefit more from prophylactic support. |

| Schreiber et al. [115] | 149 | Observational | VA-ECMO versus IABP | High-risk PCI (low LVEF and multivessel PCI) | MACE: Composite of MI, stroke, death, CABG | No difference in MACE between VA-ECMO and IABP groups. Higher multivessel PCI success rates with VA-ECMO. |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Asleh, R.; Resar, J.R. Utilization of Percutaneous Mechanical Circulatory Support Devices in Cardiogenic Shock Complicating Acute Myocardial Infarction and High-Risk Percutaneous Coronary Interventions. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8081209

Asleh R, Resar JR. Utilization of Percutaneous Mechanical Circulatory Support Devices in Cardiogenic Shock Complicating Acute Myocardial Infarction and High-Risk Percutaneous Coronary Interventions. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2019; 8(8):1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8081209

Chicago/Turabian StyleAsleh, Rabea, and Jon R. Resar. 2019. "Utilization of Percutaneous Mechanical Circulatory Support Devices in Cardiogenic Shock Complicating Acute Myocardial Infarction and High-Risk Percutaneous Coronary Interventions" Journal of Clinical Medicine 8, no. 8: 1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8081209

APA StyleAsleh, R., & Resar, J. R. (2019). Utilization of Percutaneous Mechanical Circulatory Support Devices in Cardiogenic Shock Complicating Acute Myocardial Infarction and High-Risk Percutaneous Coronary Interventions. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 8(8), 1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8081209