Abstract

Pediatric obesity continues to grow globally, specifically in low-socioeconomic rural areas. Strategies that combat pediatric obesity have not yet been fully determined. While the implementation of some interventions in preschool (ages 2–5) populations have demonstrated successful results, others have proven to be inconclusive and less have focused specifically on low socioeconomic populations. This scoping review aims to examine the literature to study the effectiveness of the school-based interventions in low socioeconomic settings on adiposity-related outcomes among preschoolers. PubMed/MEDLINE and EBSCO (ERIC (Education Resource Information Center) and Food Science Source) were used to conduct the search strategy. A total of 15 studies were assessed that met the inclusion criteria: Studies that included school-based interventions; reported adiposity-related data; targeting preschoolers (2 to 5 years old) in rural/low socioeconomic/underserved/areas. Interventions were then described as successful or inconclusive based on the primary outcome. Nine out of the fifteen studies were labeled as successful, which had a reduction in adiposity-related outcomes (BMI (body mass index), BMI z-score, waist circumference, skinfold, percent body fat). Current evidence, although scarce, suggest that obesity outcomes can be targeted in low socioeconomic settings through school interventions with a multicomponent approach (nutrition and physical activity) and the inclusion of parents. Further research is needed to determine effective interventions, their efficacy, and their long-term outcomes.

1. Introduction

Pediatric obesity is a growing global health concern. According to data from World Health Organization (WHO) in 2016, 41 million children under 5 years old were overweight or obese [1]. Overweight and obesity are defined by the WHO as “abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that presents a risk to health.” Childhood obesity has been defined using different methods for instance, WHO Child Growth Standards [1], the Center for Disease Control (CDC) (that defines overweight as a body mass index (BMI) at or above the 85th percentile while obesity is a BMI at or above the 95th percentile) [2], and the International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) [3]. Despite previous reports showing a stabilization in obesity prevalence in the United States [4], an updated review using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data by Skinner et al. (2018) [5] demonstrated that there has been a significant increase in childhood obesity and severe obesity in children 2 to 5 years old since 2013–2014 NHANES report. And according to Skinner et al. (2008) [5], this trend is continuing to grow. Although obesity is affecting children all over the world, low- and middle-income areas are the most prone [1]. Children in households that live below the poverty level in the United States show obesity rates 2.7 times higher than the average [6]. Therefore, children in underserved areas are 20% to 60% more likely to be overweight or obese compared to those with high socioeconomic status (SES) [6]. This preventable, chronic disease has started to affect preschool-aged children. Increasing obesity rates indicate increased likelihood of developing comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes and heart disease [7]. Data from the NHANES show the rate of obesity is 13.9% in preschool-aged children, ages 2 to 5 years old [8]. In comparison to the 1976–1980 NHANES survey, the prevalence of obesity has tripled [8]. Of all ages, the races that are most affected by obesity include American Indian/Alaskan Natives (18.0%), Whites (12.2%), Asian/Pacific Islanders (11.1%), African Americans (11.9%), and Latinos (17.3%) [2]. SES differences in BMI tend to emerge by four years old and increase with age [9].

Preschool may be one of the first settings where children learn behavioral norms with eating and developing eating habits that carry into adulthood [10]. Typically, there is a high preschool attendance rate in industrialized countries and therefore, school-based interventions (interventions delivered at children in an educational setting) may be most effective for the rural communities [11]. However, low SES represents an additional challenge to overcome obesity as evidence suggests that disadvantaged populations (such as low SES or rural communities) lack access to healthy foods and the resources to engage in physical activity (PA) (such as PA facilities or free activities) [7,12]. This increases the risk of poorer health choices, diet quality, and sedentary behaviors, which are all risk factors for obesity [8]. Thus, successful school interventions in such a setting may have a greater impact and may benefit at-risk populations, especially in the preschool ages.

Different school intervention studies that have been described in the literature make it apparent that implementing programs at such a young age may be the best way to tackle such a problem [8,13,14]. Although school-based intervention studies are increasing and presenting promising results, there seems to be a wide variety between the studies including the length of the study, the focus of the intervention (diet, PA, multicomponent), the target population of the intervention (children, environment, parents), and the school age or the socioeconomic level [15]. A recent review of 25 studies, based on interventions in primary school age, found that most of the studies evaluated had positive results on BMI, PA, and sedentary behavior but not with regard to nutritional behavior [16]. Multiple studies highlighted the parental involvement in the intervention to be a key piece in successful interventions [13,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Likewise, studies that include a multicomponent intervention seem to have positive results for BMI reduction, another consideration is the effect size of BMI reduction which evidence shows is still limited. However, other studies showed inconclusive results on BMI [12,25,26,27,28,29]. For example, an intervention in Germany that lasted for six months consisted of nutrition education sessions that targeted fruit and vegetable intake did not influence BMI or other anthropometric measures, such as skinfold or waist to height ratio (WTHR) in children aged 3–6 years [25]. Most reviews in current literature evaluate overall populations that are not specifically low SES. The 2003 National Survey of Children’s Health and 1996 NHANES collected data on children aged 2 to 5 years old and found that children in urban areas were 10.7% obese and 21.8% overweight, while children in rural areas were 12.2% obese and 27.2% overweight [12]. Focusing on interventions in low SES areas, which are often rural, is important to determine which aspects are successful to combat pediatric obesity. In this regard, the latest review published on disadvantaged families in 2014 focused on children ages 0–5 years showed that while the results were more successful to obesity related behaviors for those under 2 years old, specifically, for preschoolers the results were mixed. Of note this review included both studies that took place in the communities and the schools [15]. In addition, a Cochrane systematic review done by Waters et al. (2011) [30] concluded that interventions that involved an emphasis on quality of food in the school curriculum, supportive environments, parental support, and teacher support were effective in reducing adiposity specifically in ages 6–12 years. However, to our knowledge, there are no updated reviews evaluating specifically the effect of school-based intervention in low socioeconomic areas in preschoolers. Therefore, the purpose of this scoping review is to examine the literature to study the effectiveness of the school-based interventions in low socioeconomic settings on adiposity-related outcomes among preschoolers (2–5 years).

2. Materials and Methods

The research question that guided this review was: Which are the main factors of the school-based interventions to target childhood obesity or adiposity-related outcomes in preschoolers who live in rural and/or underserved areas? Because of the magnitude of this research question, a scoping review was the best fit to assess the current literature and address future research questions related to this topic. Further, given the variety of study methods on the topic, a scoping review allowed more inclusivity of study types by not assessing the quality of the study itself. This allowed the researchers to assess overall trends and gaps in the literature. The preschool population was defined as 2 to 5 years old in order to eliminate confusion, as this age group may be defined by different ages around the world.

Socioeconomic status is typically conceptualized as the social standing of an individual or group in society in relation to others and is often measured by indicators such as education, occupation, or income or a combination of these [31,32]. We included “rural areas” to point out communities with usually low SES that have health disadvantages such as less access to health care physicians, education, employment which affect health. Research shows that location where people live affects their health and life outcomes. According to the WHO, obesity is more prevalent among poor and socially disadvantaged populations in cities worldwide [33]. “Underserved populations” in the sense of subgroups face barriers to healthcare access (economic, cultural, linguistic) and lack of resources (financial, educational, housing) to make healthy choices in comparison to other socially advantaged populations. The Department of Health and Human Services characterizes underserved, vulnerable, and special communities that include members of minority populations or individuals who have experienced health disparities (e.g., Latino populations, African American populations, new mothers, and women with children etc.) [34]. In addition, Reid et al. (2008) [35], performed a meta-regression that found that there is an increased risk for poor access to health care for individuals who face economic and housing instability.

2.1. Search Strategy

The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis, extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist was followed to conduct and report this scoping review. A preliminary literature search was conducted on 19 November 2018 by a graduate student (ML) and a research librarian (HS) to assess the viability of the topic and methodology. The search string was then finalized to include appropriate MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms for PubMed/MEDLINE and adjusted the strategy and subject headings accordingly for ERIC (Education Resource Information Center) via EBSCO and Food Science Source via EBSCO. A sampling of the keywords and subject headings used to search are as follows: program; intervention; education; obesity; overweight; BMI; rural; underserved; preschool; child development center. The three electronic databases were searched with no date restriction or other limiters on February 4, 2019. Search strategies are described in Supplementary Table S1.

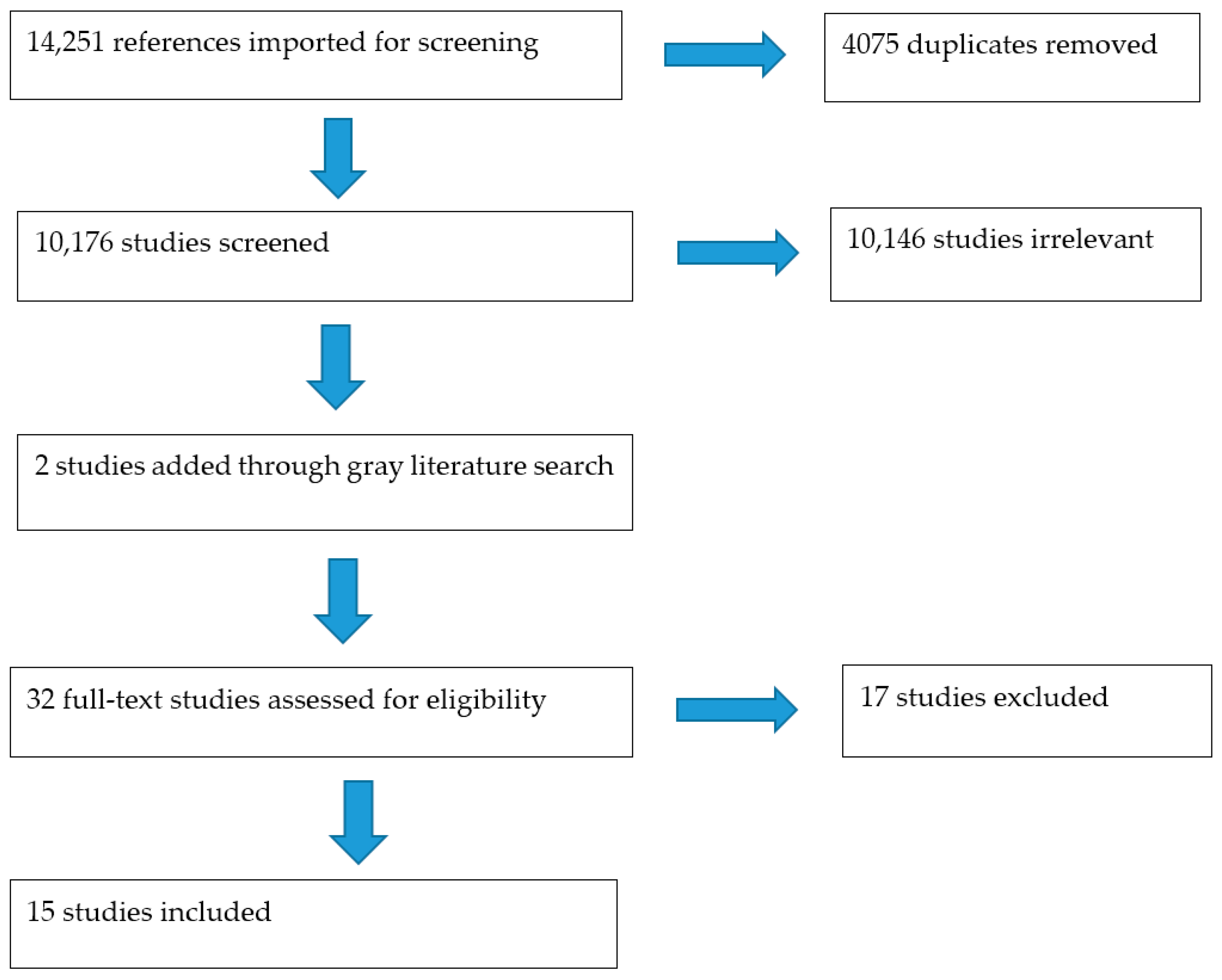

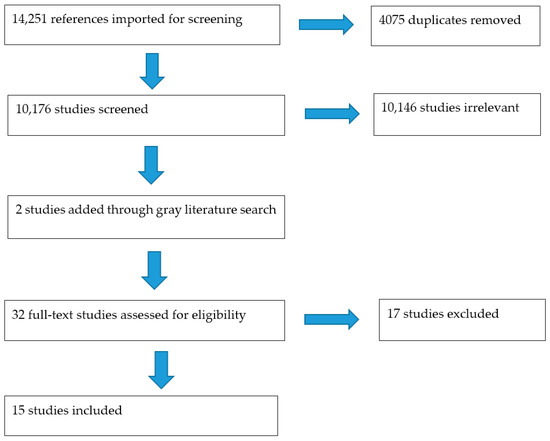

A gray literature search was performed, after full text screening, by reviewing reference lists of the original 13 selected articles. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow chart for further details on total records searched, included/excluded, and for full-text evaluation.

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis flow chart.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Covidence software through Cochrane was used to facilitate the review process. All results from the three searches were included for the first round of title/abstract screening. Covidence provided de-duplication of records. Two reviewers (MSP and ML) independently screened for predetermined inclusion/exclusion criteria, which were as follows: Studies that included school-based interventions that reported anthropometric data or obesity outcomes, targeting preschoolers (2 to 5 years old) in rural/low socioeconomic/underserved areas. Articles were excluded if obesity/anthropometric traits or the target population was not mentioned in the abstract, if interventions were community-based, and if the article did not have a translated version in English. A third person (HS) helped with discrepancies.

Covidence was also utilized for full-text screening, which two reviewers (MSP and ML) independently screened for the same criteria as mentioned above. Studies were excluded if they did not include a school-based intervention, if the population age range did not include ages 2–5 years old, if the interventions were not in a rural/low SES setting, and if the studies were not translated to English.

2.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

Final articles are summarized in Table 1, which included population characteristics, methodology, setting, and primary and secondary outcomes. Primary outcomes were specifically related to adiposity-related outcomes (BMI, BMI z-score, waist circumference, skinfold, percent of body fat, etc.) while secondary outcomes included other changes in lifestyle behaviors such as screen time, PA levels, fruit and vegetable intake etc.). Studies were then labeled as “successful”, “unsuccessful,” or “inconclusive” based on significant reductions in primary outcome or adiposity- related outcomes. Unsuccessful interventions were the ones that did not reduce the primary outcomes significantly, and inconclusive interventions were the ones that did not have an effect on the primary outcomes. Table 2 describes the interventions and the results in detail.

Table 1.

Summary of studies evaluating school-based interventions among preschoolers in low socioeconomic status (SES) settings to tackle pediatric obesity.

Table 2.

Detailed descriptions of the school-based interventions among preschoolers (ages 2–5) in low socioeconomic settings.

3. Results

The search identified 14,251 studies that were imported for screening in February 2019 before Covidence de-duplication of the records. Through title and abstract screening, 10,146 studies were irrelevant, and 30 studies were included for full-text screening. Of those 30 records, their reference lists were reviewed for final consideration of any grey literature or additional records to be added. After full-text screening, 13 studies were extracted for study. Additional two studies were included by searching citations from primary references (total studies n = 15). See Figure 1: PRISMA and Supplementary Table S1: Search strategy.

Of the final studies, 14 were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [12,13,17,18,19,20,21,22,24,25,26,27,28,29] while one was a quasi-experimental study [23]. As per our inclusion criteria all the interventions focused on preschoolers, ages 2–5 years old and typically included parental involvement. Most studies were conducted in the United States (n = 7) [12,18,19,23,26,27,28], followed by Switzerland (n = 2) [17,22], Israel (n = 2) [21,29], New Zealand (n = 1) [24], Belgium (n = 1) [13], Germany (n = 1) [25], and France (n = 1) [20].

All of the extracted studies were multicomponent interventions that targeted obesity-related outcomes (BMI z-score, waist circumference (WC), skinfold, percent body fat (%BF)). All but one [25] intervention included a PA component [25] (Table 1). Length of the interventions varied with one intervention having a follow-up of 14 weeks [27], one intervention having a follow-up of six months [21], six interventions having a follow-up of one year [17,18,22,25,28,29], six interventions having a follow-up of two years [12,13,19,20,24,26], and one with a follow-up of three years [23]. In addition, the number of children participating in each study ranged from n = 18 to n = 1926.

3.1. Successful Interventions

For this review, a successful intervention was described as one that reduced adiposity-related outcomes including BMI-z score, waist circumference, percent body fat (%BF), etc. Nine out of the fifteen interventions were successful at reducing BMI [13,17,18,19,20,21,22,24,28] (Table 1). All of the interventions were multicomponent, which included nutrition [13,17,18,19,20,21,22,28], PA [13,17,18,19,20,21,22,28], screen time [13,18,19,21,22], and economic emphasis [28]. The adiposity-related outcomes evaluated were waist circumference (WC) [17,22], %BF [17,22], and skinfold measurements [22]. Other secondary outcomes evaluated included fruit and vegetable consumption [13,17,21], water consumption [13,21], sugar-sweetened beverage consumption [13,17,21], food variety, sweet and savory snack consumption [13,17], packed lunch score [21], and sleep [21]. Parents were involved in all of the successful interventions. The length of the studies were six months to three years and the sample size was 146 to 1816 preschoolers. The efficacy of the most successful intervention was conducted in Switzerland. Results found a successfully reduced %BF by 5%, sum of skinfolds by 10%, and WC by 2% [22]. Children were engaged in four 45-min PA sessions/week that targeted aerobic fitness (Table 2). Lessons (n = 22) were based on the five recommendations of the Swiss Society of Nutrition: (1) drink water, (2) eat fruits and vegetables, (3) eat regularly, (4) make clever choices, (5) turn your screen off when you eat. Parent involvement and modification in the classroom environment was also targeted as part of the intervention. Despite anthropometric traits, beneficial effects were also shown in PA, nutrition habits, and media use [22].

All successful interventions provided preschoolers with educational nutrition lessons and PA sessions. The majority of successful interventions incorporated themes and/or activities into their lessons. One intervention based in Switzerland focused on themes, such as Spiderman, to reinforce learning [17], while another intervention in France paired games that aimed to increase nutrition knowledge about the food groups, eating balanced meals, and drinking more water [20]. Fitzgibbon et al. (2005) [19] modeled the nutrition lessons after “Go and Grow” foods to teach the food pyramid. Other studies focused on educating preschoolers about healthy choices during the nutrition lesson. PA sessions ranged from 20–45 min long. Parents were involved in each intervention by receiving educational handouts, attending educational sessions, and/or receiving guided PA CDs [13,18,21,28]. Anthropometric measures improved in each intervention. Four out of the nine interventions lowered BMI z-score [13,17,18,20,21]. The intervention conducted by Kaufman-Shriqui et al. (2016) [21] proved to decrease BMI z-score in both the intervention (IArm) and control (CArm) groups. Although there were no anthropometric differences in the results between IArm and CArm, we still consider this to be a successful intervention due to CArm still receiving the PA component.

Two out of the nine successful studies incorporated an economic change, policy change, or environmental change in their intervention [22,23]. An intervention in Switzerland focused on environmental change by changing the layouts of classrooms to promote PA [22]. Changes included adding hammocks, balls, and climbing walls [22]. Lastly, an intervention in California focused on an economic component and encouraged parents to buy budget-friendly nutritious foods. Modeled after WIC (Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for low income Women, Infants, and Children, a US federal assistant program) program families received $25 vouchers that could only be used to buy fruits and vegetables [23].

3.2. Inconvlusive Interventions

Inconclusive interventions were described as the ones that did not significantly reduce anthropometric measures. One study proved to be null with no positive outcomes [26]. Six out of fifteen interventions failed to reduce BMI and/or BMI z-score [12,25,26,27,28,29]. All of the interventions were multicomponent, which included nutrition, PA, media use, and sleep. The studies evaluated the association of the intervention with different obesity-related measures, including BMI z-score, %BF, WTHR, and skinfold. Other outcomes evaluated included aerobic fitness, screen time, and consumption of water, milk, vegetables, fruits, soft drinks, sweet, dietary fat, fiber, and savory snacks. Parents were involved in all of the six inconclusive interventions. The length of the studies were fourteen weeks to two years and the sample size was 377 to 1926 preschoolers.

All interventions provided preschoolers with educational lessons or informational sessions about proper nutrition and PA. Each had themes or activities incorporated into the interventions. Three of the studies incorporated puppets or pirate dolls to reinforce learning [25,26,27]. Three studies utilized scripted exercise CDs, which were translated into multiple languages to be accessible to parents, that led the children in a short PA activity [27,28,29]. Other studies incorporated activities that were aimed at trying new healthy foods or making healthy snacks in the classroom [25,28]. Although a reduction in BMI did not occur in these studies, other positive outcomes were reported. Bock et al. (2011) [25] reported an increase in vegetable intake (0.027) [25]. Fitzgibbon et al. (2006) [26] did not report any significant conclusions, while in a later study the same author (Fitzgibbon et al., 2011) [27] reported a decreased screen time (–27.8 min/day (–55.1 to −0.5), p = 0.05) and increased moderate to vigorous activity (MVPA) compared to the control group (moderate, 4.78 min/day (0.10 to 9.45); p = 0.05 and vigorous, 2.83 min/day (−1.8 to 66.9), p = 0.03). An intervention in Chicago reported that the intervention group increased intake in whole fruit (p = 0.02), total fruit (p = 0.003), and whole grains (p = 0.02) compared to control group [28]. Lastly, the intervention in Israel, modeled after the Israeli Ministry of Education program called “It Fits Me,” indicated an increase in nutrition and PA knowledge and preferences (p < 0.05) in the intervention group [29].

3.3. Theoretical Frameworks

Six out of the fifteen studies based their interventions on theoretical models [13,18,23,25,26,27] and of those six, three were successful interventions [13,18,23]. Theoretical models mentioned were theory of social learning, social cognitive theory, self-determination theory, socioecological model of health, and health belief model. Bock et al. (2011) [25] based the parental component of the intervention on the theory of social learning. The theory of social learning in the context of learning food behaviors suggests that children learn by imitating their parents and peers. Therefore, including parents in the intervention is important when changing child behavior [25]. Coen et al. (2011) [13] based their intervention on the socioecological model of health, which emphasizes on the child while considering the several layers of interaction around them (parents, friends, media etc.). Fitzgibbon et al. (2006), (2011), and (2013) based their interventions on social cognitive theory and self-determination theory. Fitzgibbon et al. (2013) [18] also included the health belief model. Sadeghi et al. (2016) [23] based their interventions on the social cognitive theory and the health belief model.

4. Discussion

This scoping review aimed to examine the effectiveness of school-based interventions that targeted pediatric obesity in preschool children (ages 2–5) in low-SES areas. A total of 15 interventions met the inclusion criteria: Studies that included school-based interventions; reported obesity related/anthropometric outcomes; targeting preschoolers (2 to 5 years old) in rural/low socioeconomic/underserved areas. Nine out of the fifteen studies were considered to be successful while five studies were inconclusive, and one was null. Successful interventions demonstrated significant reductions in BMI-related anthropometric measures. Both successful and inconclusive interventions included PA and nutrition components and also involved parents as part of the targeted intervention.

Reviews and systematic reviews on obesity prevention that include general population and a broad range of children ages (0–14 years) and settings [36,37,38,39] are in line with the successful interventions that we reported. Interventions that promote healthy eating in preschoolers thrive when paired with other components, such as PA [10]. Additionally, the two components that all successful interventions had in common are parental and child involvement. Intervention activities geared toward the preschoolers were most successful when the children were engaged in interactive learning, such as taste testing, playing games, and singing songs [10,21]. Parent sessions were focused on nutrition, PA education, and how healthy food shopping can be budget-friendly [13,18,21,22]. While successful interventions varied in duration, they all aimed to increase nutrition knowledge, PA, and decrease obesity-related anthropometric measures [10,12,13,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24].

Our findings support current literature in that successful obesity-prevention interventions for preschoolers are multicomponent [10,15]. Parental involvement in successful interventions is crucial in order to intervene in pediatric obesity [16,40]. Focusing on parents in addition to their preschoolers is important because their attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors contribute to weight gain in their child [41]. These behaviors, such as feeding styles, role modeling, and sharing nutritional knowledge with their children have been associated with their children’s weight, eating habits, and PA levels [36,37,41,42]. Implementing parental involvement in such interventions may encourage children to try new foods and model healthy eating behaviors after their parents [36,41,42]. The importance of parental involvement was also supported by Verjans-Janssen et al. (2018) [16] by suggesting that the parental component should be the primary focus of such interventions. Thus, focusing on parent–child bonding may increase parents’ interest in participating. Implementing interventions in more diverse populations will allow for a better understanding of how to implement a family-based component [38]. Although all the interventions evaluated in this scoping review were multicomponent, the intensity and the delivery mode as well as the content may affect the success of the intervention. For example, Burgi et al. (2012) [17] included a reward system in class with stickers that may keep children’s motivation. Others included well-known characters “Spiderman” to engage kids to change behaviors.

Theoretical-based interventions were scarce as has been mentioned previously. Only six interventions included theoretical models [13,18,23,25,26,27] and three were successful in reducing obesity outcomes [13,18,23]. Future studies should consider elaborating their interventions based on a theoretical model.

Affordability and food costs may be a barrier for families living in rural/low SES areas. Economic change, policy change, and environmental change might be an important point to take into account when implementing obesity school-based interventions, in particular, in low SES settings, however there are not enough studies evaluating these strategies. Research shows that a majority of people associate eating healthy with being expensive; however, a systematic review and meta-analysis by Rao et al. (2013) [43] evaluated studies from 10 different countries. Significant monetary differences occurred in meats/protein with healthier options costing $0.47/200 kcal and $0.29/serving more than less healthy meats/proteins. Price differences were less significant in healthier grain and dairy options ($0.03/serving and −$0.004/serving, respectively). Thus, eating a healthy and balanced diet cost $1.48/day and $1.54/2000 kcal more than a less healthy diet [16]. Although, McDermott et al. (2010) [44] specifically analyzed low-income, single-parent populations and the monetary difference between food shopping at a supermarket and eating primarily fast-food (convenience diet). Using cost-per-calorie analysis, convenience diets accounted for 37% of income, while a healthy diet accounted for only 18% of income. Sadeghi et al. (2016) [23] provided monetary incentives in the form of a voucher for families to spend on fruit and vegetables in addition to “family nights” when nutrition lessons would be held. However, more research is needed to determine if vouchers are a successful component to incentivize healthy eating. Educating parents on how to plan a long term healthy and sustainable menu within a budget may help them to have healthy choices and thus, help decrease obesity outcomes.

Low SES populations are highly specific and may not adhere to a general obesity intervention. These populations along with minority youth are at an increased risk for obesity, type 2 diabetes, and other comorbidities [45,46,47]. For example, Latinos face barriers that non-minority populations do not, such as limited access to health insurance, language and cultural barriers [47,48]. Additionally, a popular perception in the Latino population is that the heavier the child, the healthier [49,50]. Thus, interventions targeting low SES and minority youths require tailored interventions specific to the population. To demonstrate the need for tailored interventions, Falbe et al. (2015) [47] conducted a 10-week active and healthy families (AHF) intervention that targeted Latino youth aged 5 to 12 years old. The intervention consisted of five 2-h group medical appointments, which focused on topics such as, obesity, nutrition labels, healthy snacks, PA, emotional eating, portion sizes, fast food, parenting, stress, and immigration. PA sessions were implemented during parent–physician discussions. Results showed a decrease in BMI in the AHF group (−0.50 kg/m2, CI (−1.28, −0.27)) [47]. Tailoring interventions to the culture are also supported by a systematic review by Tovar et al. (2014) [51]. Successful interventions in youth had a cultural focus, which facilitated community engagement and parental involvement. Based on the results from this scoping review, studies in this regard are still scarce, and more research is needed in order to determine which components have the best effect in low SES and minority youth populations.

Strengths of this scoping review include a unique focus on preschoolers (ages 2–5), low SES populations, and school-based interventions. Two researchers were used to screen all studies through a systematic search process, and disagreements were decided by a third person (HS). Limitations include not including search terms that represented different languages. We did not limit to English specifically, but that is inherent in our search strategies. There were also limited studies for a global focus, which can be due to the language limitations. Additionally, defining these programs was difficult and may be due to different definitions (i.e., preschool) throughout the world, but it was also limited to the databases we searched. Lastly, there is no way to be all inclusive in a gray literature search and due to a small effect size of successful interventions, we do not have enough successful interventions to make a conclusion.

5. Conclusions

Based on our results, multicomponent school-based interventions targeting low SES preschool children should include a nutrition and PA component and involve parents as agents of change. Although there is not an outstanding component that can discriminate successful vs. inconclusive interventions, future studies should focus on culturally tailored interventions, consider exploring and including economic change (know how to be healthy within a friendly budget), school environment, and assess motivation and engagement of children to achieve healthy behaviors that translate into obesity reduction. In addition, the interventions may be more effective if hands-on learning were involved by integrating a structured food education framework. However, so far, the literature is still limited, and the evidence is scarce, and more research with rigorous evaluation and high-quality study designs that focus on disadvantage/undeserved/low SES population are needed to establish key components to reduce pediatric obesity in low SES settings.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/11/7/1518/s1, Table S1: Search Strategy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S.P., M.L.; methodology, H.S., M.L.; validation, M.S.P., M.L.; formal analysis, M.S.P., M.L.; investigation, M.S.P., M.L.; resources, M.S.P., M.L., H.S.; data curation, M.S.P., M.L., H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.P., M.L., H.S.; writing—review and editing, M.S.P., M.L., H.S.; visualization, M.S.P., M.L., H.S.; supervision, M.S.P.; project administration, M.S.P.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 12 June 2019).

- Defining Childhood Obesity. Overweight & Obesity. CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/childhood/defining.html (accessed on 14 June 2019).

- Cole, T.J.; Flegal, K.M.; Nicholls, D.; Jackson, A.A. Body Mass Index Cut Offs to Define Thinness in Children and Adolescents: International Survey. BMJ 2007, 335, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogden, C.L.; Carroll, M.D.; Lawman, H.G.; Fryar, C.D.; Kruszon-Moran, D.; Kit, B.K.; Flegal, K.M. Trends in Obesity Prevalence Among Children and Adolescents in the United States, 1988–1994 Through 2013–2014. JAMA 2016, 315, 2292–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, A.C.; Ravanbakht, S.N.; Skelton, J.A.; Perrin, E.M.; Armstrong, S.C. Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity in US Children, 1999–2016. Pediatrics 2018, 141, e20173459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The State of Obesity. Available online: https://www.stateofobesity.org/childhood-obesity-trends/ (accessed on 21 September 2018).

- Lobstein, T.; Baur, L.; Uauy, R. Obesity in Children and Young People: A Crisis in Public Health. Obes. Rev. 2004, 5 (Suppl. 1), 4–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/factsheets/factsheet_nhanes.htm (accessed on 21 September 2018).

- Howe, L.D.; Tilling, K.; Galobardes, B.; Smith, G.D.; Ness, A.R.; Lawlor, D.A. Socioeconomic Disparities in Trajectories of Adiposity across Childhood. Int. J. Pediatr. Obes. 2011, 6 (Suppl. 3), e144–e153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nekitsing, C.; Hetherington, M.M.; Blundell-Birtill, P. Developing Healthy Food Preferences in Preschool Children Through Taste Exposure, Sensory Learning, and Nutrition Education. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2018, 7, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boocock, S.S. Early Childhood Programs in Other Nations: Goals and Outcomes. Future Child. 1995, 5, 94–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, S.M.; Myers, O.B.; Cruz, T.H.; Morshed, A.B.; Canaca, G.F.; Keane, P.C.; O’Donald, E.R. CHILE: Outcomes of a Group Randomized Controlled Trial of an Intervention to Prevent Obesity in Preschool Hispanic and American Indian Children. Prev. Med. 2016, 89, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coen, V.D.; Bourdeaudhuij, I.D.; Vereecken, C.; Verbestel, V.; Haerens, L.; Huybrechts, I.; Lippevelde, W.V.; Maes, L. Effects of a 2-Year Healthy Eating and Physical Activity Intervention for 3–6-Year-Olds in Communities of High and Low Socio-Economic Status: The POP (Prevention of Overweight among Pre-School and School Children) Project. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 1737–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerbell, C.D.; Waters, E.; Edmunds, L.; Kelly, S.A.; Brown, T.; Campbell, K.J. Interventions for Preventing Obesity in Children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2005, CD001871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laws, R.; Campbell, K.J.; van der Pligt, P.; Russell, G.; Ball, K.; Lynch, J.; Crawford, D.; Taylor, R.; Askew, D.; Denney-Wilson, E. The Impact of Interventions to Prevent Obesity or Improve Obesity Related Behaviours in Children (0–5 Years) from Socioeconomically Disadvantaged and/or Indigenous Families: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verjans-Janssen, S.R.B.; van de Kolk, I.; Van Kann, D.H.H.; Kremers, S.P.J.; Gerards, S.M.P.L. Effectiveness of School-Based Physical Activity and Nutrition Interventions with Direct Parental Involvement on Children’s BMI and Energy Balance-Related Behaviors—A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bürgi, F.; Niederer, I.; Schindler, C.; Bodenmann, P.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Kriemler, S.; Puder, J.J. Effect of a Lifestyle Intervention on Adiposity and Fitness in Socially Disadvantaged Subgroups of Preschoolers: A Cluster-Randomized Trial (Ballabeina). Prev. Med. 2012, 54, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzgibbon, M.L.; Stolley, M.R.; Schiffer, L.; Kong, A.; Braunschweig, C.L.; Gomez-Perez, S.L.; Odoms-Young, A.; Van Horn, L.; Christoffel, K.K.; Dyer, A.R. Family-Based Hip-Hop to Health: Outcome Results. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013, 21, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgibbon, M.L.; Stolley, M.R.; Schiffer, L.; Van Horn, L.; KauferChristoffel, K.; Dyer, A. Two-Year Follow-up Results for Hip-Hop to Health Jr.: A Randomized Controlled Trial for Overweight Prevention in Preschool Minority Children. J. Pediatr. 2005, 146, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouret, B.; Ahluwalia, N.; Dupuy, M.; Cristini, C.; Nègre-Pages, L.; Grandjean, H.; Tauber, M. Prevention of Overweight in Preschool Children: Results of Kindergarten-Based Interventions. Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, 1075–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman-Shriqui, V.; Fraser, D.; Friger, M.; Geva, D.; Bilenko, N.; Vardi, H.; Elhadad, N.; Mor, K.; Feine, Z.; Shahar, D.R. Effect of a School-Based Intervention on Nutritional Knowledge and Habits of Low-Socioeconomic School Children in Israel: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2016, 8, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puder, J.J.; Marques-Vidal, P.; Schindler, C.; Zahner, L.; Niederer, I.; Bürgi, F.; Ebenegger, V.; Nydegger, A.; Kriemler, S. Effect of Multidimensional Lifestyle Intervention on Fitness and Adiposity in Predominantly Migrant Preschool Children (Ballabeina): Cluster Randomised Controlled Trial. BMJ 2011, 343, d6195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, B.; Kaiser, L.L.; Schaefer, S.; Tseregounis, I.E.; Martinez, L.; Gomez-Camacho, R.; de la Torre, A. Multifaceted Community-Based Intervention Reduces Rate of BMI Growth in Obese Mexican-Origin Boys. Pediatr. Obes. 2017, 12, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rush, E.; Reed, P.; McLennan, S.; Coppinger, T.; Simmons, D.; Graham, D. A School-Based Obesity Control Programme: Project Energize. Two-Year Outcomes. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 107, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bock, F.D.; Breitenstein, L.; Fischer, J.E. Positive Impact of a Pre-School-Based Nutritional Intervention on Children’s Fruit and Vegetable Intake: Results of a Cluster-Randomized Trial. Public Health Nutr. 2012, 15, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgibbon, M.L.; Stolley, M.R.; Schiffer, L.; Van Horn, L.; KauferChristoffel, K.; Dyer, A. Hip-Hop to Health Jr. for Latino Preschool Children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006, 14, 1616–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgibbon, M.L.; Stolley, M.R.; Schiffer, L.A.; Braunschweig, C.L.; Gomez, S.L.; Van Horn, L.; Dyer, A.R. Hip-Hop to Health Jr. Obesity Prevention Effectiveness Trial: Postintervention Results. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011, 19, 994–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, A.; Buscemi, J.; Stolley, M.R.; Schiffer, L.A.; Kim, Y.; Braunschweig, C.L.; Gomez-Perez, S.L.; Blumstein, L.B.; Van Horn, L.; Dyer, A.R.; et al. Hip-Hop to Health Jr. Randomized Effectiveness Trial: 1-Year Follow-up Results. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 50, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemet, D.; Geva, D.; Eliakim, A. Health Promotion Intervention in Low Socioeconomic Kindergarten Children. J. Pediatr. 2011, 158, 796–801.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, E.; de Silva-Sanigorski, A.; Hall, B.J.; Brown, T.; Campbell, K.J.; Gao, Y.; Armstrong, R.; Prosser, L.; Summerbell, C.D. Interventions for Preventing Obesity in Children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2011, CD001871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakes, J.M.; Rossi, P.H. The Measurement of SES in Health Research: Current Practice and Steps toward a New Approach. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 56, 769–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Condition of Education—Glossary. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/glossary.asp (accessed on 15 June 2019).

- WHO. Commission on Social Determinants of Health (Report); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008; Available online: https://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/finalreport/en/ (accessed on 15 June 2019).

- Serving Vulnerable and Underserved Populations. 130p. Available online: https://marketplace.cms.gov/technical-assistance-resources/training-materials/vulnerable-and-underserved-populations.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2019).

- Reid, K.W.; Vittinghoff, E.; Kushel, M.B. Association between the Level of Housing Instability, Economic Standing and Health Care Access: A Meta-Regression. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2008, 19, 1212–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrow, C.V.; Blissett, J. Controlling Feeding Practices: Cause or Consequence of Early Child Weight? Pediatrics 2007, 121, e164–e169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Addessi, E.; Galloway, A.T.; Visalberghi, E.; Birch, L.L. Specific Social Influences on the Acceptance of Novel Foods in 2–5-Year-Old Children. Appetite 2005, 45, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ash, T.; Agaronov, A.; Young, T.; Aftosmes-Tobio, A.; Davison, K.K. Family-Based Childhood Obesity Prevention Interventions: A Systematic Review and Quantitative Content Analysis. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, J.; Robbins, L.B.; Wen, F. Interventions to Prevent and Manage Overweight or Obesity in Preschool Children: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 53, 270–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bleich, S.N.; Vercammen, K.A.; Zatz, L.Y.; Frelier, J.M.; Ebbeling, C.B.; Peeters, A. Interventions to Prevent Global Childhood Overweight and Obesity: A Systematic Review. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018, 6, 332–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skouteris, H.; McCabe, M.; Swinburn, B.; Newgreen, V.; Sacher, P.; Chadwick, P. Parental Influence and Obesity Prevention in Pre-Schoolers: A Systematic Review of Interventions. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faith, M.S.; Scanlon, K.S.; Birch, L.L.; Francis, L.A.; Sherry, B. Parent-Child Feeding Strategies and Their Relationships to Child Eating and Weight Status. Obes. Res. 2004, 12, 1711–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, M.; Afshin, A.; Singh, G.; Mozaffarian, D. Do Healthier Foods and Diet Patterns Cost More than Less Healthy Options? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 2013, 3, e004277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, A.J.; Stephens, M.B. Cost of Eating: Whole Foods Versus Convenience Foods in a Low-Income Model. Fam. Med. 2010, 42, 280–284. [Google Scholar]

- Ogden, C.L.; Lamb, M.M.; Carroll, M.D.; Flegal, K.M. Obesity and Socioeconomic Status in Children and Adolescents: United States, 2005–2008. NCHS Data Brief 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, D.S.; Mei, Z.; Srinivasan, S.R.; Berenson, G.S.; Dietz, W.H. Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Excess Adiposity Among Overweight Children and Adolescents: The Bogalusa Heart Study. J. Pediatr. 2007, 150, 12–17.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falbe, J.; Cadiz, A.A.; Tantoco, N.K.; Thompson, H.R.; Madsen, K.A. Active and Healthy Families: A Randomized Controlled Trial of a Culturally Tailored Obesity Intervention for Latino Children. Acad. Pediatr. 2015, 15, 386–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juckett, G. Caring for Latino Patients. AFP 2013, 87, 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, P.B.; Gosliner, W.; Anderson, C.; Strode, P.; Becerra-Jones, Y.; Samuels, S.; Carroll, A.M.; Ritchie, L.D. Counseling Latina Mothers of Preschool Children about Weight Issues: Suggestions for a New Framework. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2004, 104, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsay, A.C.; Sussner, K.M.; Greaney, M.L.; Peterson, K.E. Latina Mothers’ Beliefs and Practices Related to Weight Status, Feeding, and the Development of Child Overweight. Public Health Nurs. 2011, 28, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tovar, A.; Renzaho, A.M.N.; Guerrero, A.D.; Mena, N.; Ayala, G.X. A Systematic Review of Obesity Prevention Intervention Studies among Immigrant Populations in the US. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2014, 3, 206–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).