Quantifying Diet Intake and Its Association with Cardiometabolic Risk in the UK Airwave Health Monitoring Study: A Data-Driven Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Study Design

2.2. Dietary Assessment

2.3. Diet Exposure Quantification

2.4. Anthropometric, Blood Pressure and Biochemical Measurements

2.5. Outcome Definition: Cardiometabolic Risk

- Central adiposity (waist circumference ≥ 94 cm [men] and ≥ 80 cm [women]),

- Dyslipidemia (HDL <1.0 mmol/L [men] and <1.3 mmol/L [women], and/or non-HDL ≥ 4.0 mmol/L, and/or prescribed lipid lowering medication),

- Elevated blood pressure (systolic ≥ 130 mmHg, and/or diastolic ≥ 85 mmHg, and/or prescribed hypotensive medication),

- Inflammation (Hs-CRP ≥ 3 mg/L < 10 mg/L),

- Impaired blood glucose control: HbA1c ≥ 5.7% and/or prescribed medication for glucose control)

2.6. Covariate Assessment

2.7. Statistical Methods

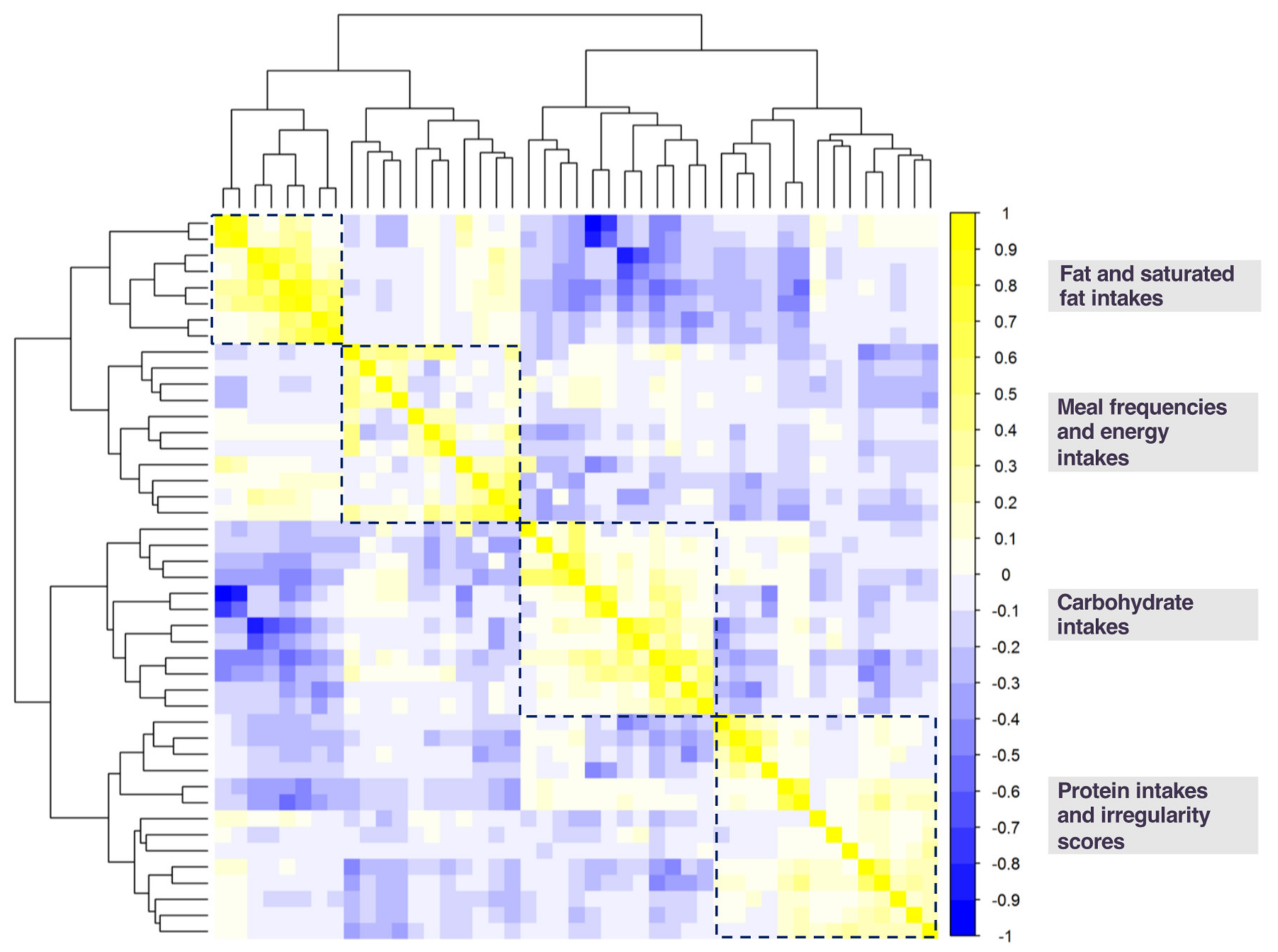

2.7.1. Dimension Reduction Techniques and Diet Exposure Selection

2.7.2. Examination of Association Between Identified Diet Exposures and Cardiometabolic Risk

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Diet Exposures Selected by K-means Cluster Analysis

3.3. Diet Exposure Association with Cardiometabolic Risk

3.4. Post Hoc Analyses

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statistics on Obesity, Physical Activity and Diet—England, 2018 [PAS]—NHS Digital. Available online: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/statistics-on-obesity-physical-activity-and-diet/statistics-on-obesity-physical-activity-and-diet-england-2018 (accessed on 10 April 2019).

- Heart Statistics—Heart and Circulatory Diseases in the UK—BHF. Available online: https://www.bhf.org.uk/what-we-do/our-research/heart-statistics (accessed on 10 April 2019).

- Alfonso, I.N.G.; Meza, T.; Trejo, A.; Valladares, A. Projections of Cardiovascular Disease Prevalence and Costs: 2015–2035. RTI International: Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Key, T.J.; Appleby, P.N.; Bradbury, K.E.; Sweeting, M.; Wood, A.; Johansson, I.; Kühn, T.; Steur, M.; Weiderpass, E.; Wennberg, M.; et al. Consumption of Meat, Fish, Dairy Products, and Eggs and Risk of Ischemic Heart Disease. Circulation 2019, 139, 2835–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purslow, L.R.; Sandhu, M.S.; Forouhi, N.; Young, E.H.; Luben, R.N.; Welch, A.A.; Khaw, K.-T.; Bingham, S.A.; Wareham, N.J. Energy Intake at Breakfast and Weight Change: Prospective Study of 6,764 Middle-aged Men and Women. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 167, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlEssa, H.B.; Cohen, R.; Malik, V.S.; Adebamowo, S.N.; Rimm, E.B.; Manson, J.E.; Willett, W.C.; Hu, F.B. Carbohydrate quality and quantity and risk of coronary heart disease among US women and men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2018, 107, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Onge, M.P.; Ard, J.; Baskin, M.L.; Chiuve, S.E.; Johnson, H.M.; Kris-Etherton, P.; Varady, K. Meal Timing and Frequency: Implications for Cardiovascular Disease Prevention: A Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017, 135, e96–e121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garaulet, M.; Gómez-Abellán, P. Timing of food intake and obesity: A novel association. Physiol. Behav. 2014, 134, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattson, M.P.; Allison, D.B.; Fontana, L.; Harvie, M.; Longo, V.D.; Malaisse, W.J.; Mosley, M.; Notterpek, L.; Ravussin, E.; Scheer, F.A.J.L.; et al. Meal frequency and timing in health and disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 16647–16653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Paoli, A.; Tinsley, G.; Bianco, A.; Moro, T. The influence of meal frequency and timing on health in humans: The role of fasting. Nutrients 2019, 11, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marianna, P.; Iolanda, C.; Andrea, E.; Valentina, P.; Ilaria, G.; Giovannino, C.; Ezio, G.; Simona, B. Effects of time-restricted feeding on body weight and metabolism. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2020, 21, 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y. Association between Eating Patterns and Obesity in a Free-living US Adult Population. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 158, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pot, G.K.; Hardy, R.; Stephen, A.M. Irregular consumption of energy intake in meals is associated with a higher cardiometabolic risk in adults of a British birth cohort. Int. J. Obes. 2014, 38, 1518–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schoenfeld, J.D.; Ioannidis, J.P. Is everything we eat associated with cancer? A systematic cookbook review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 97, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Keogh, R.H.; White, I.R. A toolkit for measurement error correction, with a focus on nutritional epidemiology. Stat. Med. 2014, 33, 2137–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Elliott, P.; Vergnaud, A.-C.; Singh, D.; Neasham, D.; Spear, J.; Heard, A. The Airwave Health Monitoring Study of police officers and staff in Great Britain: Rationale, design and methods. Environ. Res. 2014, 134, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nelson, M.; Haraldsdóttir, J. Food photographs: Practical guidelines II. Development and use of photographic atlases for assessing food portion size. Public Health Nutr. 1998, 1, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gibson, R.; Eriksen, R.; Lamb, K.; McMeel, Y.; Vergnaud, A.-C.; Spear, J.; Aresu, M.; Chan, Q.; Elliott, P.; Frost, G. Dietary assessment of British police force employees: A description of diet record coding procedures and cross-sectional evaluation of dietary energy intake reporting (The Airwave Health Monitoring Study). BMJ Open 2017, 7, e012927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibney, M.J.; wolever, T.M.S. Periodicity of eating and human health: Present perspective and future directions. Br. J. Nutr. 1997, 77, S3–S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, R.; Eriksen, R.; Singh, D.; Vergnaud, A.-C.; Heard, A.; Chan, Q.; Elliott, P.; Frost, G. A cross-sectional investigation into the occupational and socio-demographic characteristics of British police force employees reporting a dietary pattern associated with cardiometabolic risk: Findings from the Airwave Health Monitoring Study. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 2913–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-Country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- IPAQ Scoring Protocol—International Physical Activity Questionnaire. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/theipaq/scoring-protocol (accessed on 26 January 2020).

- Millen, B.E.; Quatromoni, P.A.; Copenhafer, D.L.; Demissie, S.; O’Horo, C.E.; D’Agostino, R.B. Validation of a dietary pattern approach for evaluating nutritional risk: The Framingham Nutrition Studies. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2001, 101, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millen, B.E.; Quatromoni, P.A.; Gagnon, D.R.; Cupples, L.A.; Franz, M.M.; D’Agostino, R.B. Dietary patterns of men and women suggest targets for health promotion: The Framingham nutrition studies. Am. J. Health Promot. 1996, 11, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryer, J.A.; Nichols, R.; Elliott, P.; Thakrar, B.; Brunner, E.; Marmot, M. Dietary patterns among a national random sample of British adults. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2001, 55, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leech, R.M.; Worsley, A.; Timperio, A.; McNaughton, S.A. Temporal eating patterns: A latent class analysis approach. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2017, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mouselimis, L.; ClusterR: Gaussian Mixture Models, K-Means, Mini-Batch-Kmeans, K-Medoids and Affinity Propagation Clustering. R package version 1.2.0. 2019. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ClusterR (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- Maechler, M.; Rousseeuw, P.; Struyf, A.; Hubert, M.; Hornik, K.; Cluster: Cluster Analysis Basics and Extensions. R package version 2.1.0. 2019. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=cluster (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- Charrad, M.; Ghazzali, N.; Boiteau, V.; Niknafs, A. NbClust: An R Package for Determining the Relevant Number of Clusters in a Data Set. J. Stat. Softw. 2014, 61, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wei, T.; Simko, V. R Package “Corrplot”: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix (Version 0.84). 2017. Available online: https://github.com/taiyun/corrplot (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- Zhang, J.; Yu, K.F. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1998, 280, 1690–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tamhane, A.R.; Westfall, A.O.; Burkholder, G.A.; Cutter, G.R. Prevalence odds ratio versus prevalence ratio: Choice comes with consequences. Stat. Med. 2016, 35, 5730–5735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ferrannini, E.; Haffner, S.M.; Mitchell, B.D.; Stern, M.P. Hyperinsulinaemia: The key feature of a cardiovascular and metabolic syndrome. Diabetologia 1991, 34, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaak, E.E. Carbohydrate quantity and quality and cardio-metabolic risk. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2016, 19, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shai, I.; Schwarzfuchs, D.; Henkin, Y.; Shahar, D.R.; Witkow, S.; Greenberg, I.; Golan, R.; Fraser, D.; Bolotin, A.; Vardi, H.; et al. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McKeown, N.M.; Meigs, J.B.; Liu, S.; Saltzman, E.; Wilson, P.W.F.; Jacques, P.F. Carbohydrate Nutrition, Insulin Resistance, and the Prevalence of the Metabolic Syndrome in the Framingham Offspring Cohort. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McKeown, N.M.; Meigs, J.B.; Liu, S.; Wilson, P.W.F.; Jacques, P.F. Whole-grain intake is favorably associated with metabolic risk factors for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease in the Framingham Offspring Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2002, 76, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Babio, N.; Bulló, M.; Salas-Salvadó, J. Mediterranean diet and metabolic syndrome: The evidence. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 1607–1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Snorgaard, O.; Poulsen, G.M.; Andersen, H.K.; Astrup, A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary carbohydrate restriction in patients with type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludwig, D.S.; Ebbeling, C.B. The carbohydrate-insulin model of obesity: Beyond “calories in, calories out. ” JAMA Intern. Med. 2018, 178, 1098–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diabetes and Carbs | Eat Well with Diabetes | CDC. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/managing/eat-well/diabetes-and-carbohydrates.html (accessed on 27 January 2020).

- Volek, J.S.; Phinney, S.D.; Forsythe, C.E.; Quann, E.E.; Wood, R.J.; Puglisi, M.J.; Kraemer, W.J.; Bibus, D.M.; Fernandez, M.L.; Feinman, R.D. Carbohydrate Restriction has a More Favorable Impact on the Metabolic Syndrome than a Low Fat Diet. Lipids 2009, 44, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lofgren, I.E.; Herron, K.L.; West, K.L.; Zern, T.L.; Brownbill, R.A.; Ilich, J.Z.; Koo, S.I.; Fernandez, M.L. Weight loss favorably modifies anthropometrics and reverses the metabolic syndrome in premenopausal women. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2005, 24, 486–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, R.J.; Fernandez, M.L.; Sharman, M.J.; Silvestre, R.; Greene, C.M.; Zern, T.L.; Shrestha, S.; Judelson, D.A.; Gomez, A.L.; Kraemer, W.J.; et al. Effects of a carbohydrate-restricted diet with and without supplemental soluble fiber on plasma low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and other clinical markers of cardiovascular risk. Metabolism 2007, 56, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidelmann, S.B.; Claggett, B.; Cheng, S.; Henglin, M.; Shah, A.; Steffen, L.M.; Folsom, A.R.; Rimm, E.B.; Willett, W.C.; Solomon, S.D. Dietary carbohydrate intake and mortality: A prospective cohort study and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2018, 3, e419–e428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Appendix 7. Nutritional Goals for Age-Sex Groups Based on Dietary Reference Intakes and Dietary Guidelines Recommendations—2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines|health.gov. Available online: https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/appendix-7/ (accessed on 27 January 2020).

- Duffey, K.J.; Pereira, R.A.; Popkin, B.M. Prevalence and energy intake from snacking in Brazil: Analysis of the first nationwide individual survey. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013, 67, 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatenby, S.J. Eating frequency: Methodological and dietary aspects. Br. J. Nutr. 1997, 77, S7–S20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hampl, J.S.; Heaton, C.L.B.; Taylor, C.A. Snacking patterns influence energy and nutrient intakes but not body mass index. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2003, 16, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovaskainen, M.L.; Reinivuo, H.; Tapanainen, H.; Hannila, M.L.; Korhonen, T.; Pakkala, H. Snacks as an element of energy intake and food consumption. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 60, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titan, S.M.O.; Bingham, S.; Welch, A.; Luben, R.; Oakes, S.; Day, N.; Khaw, K.T. Frequency of eating and concentrations of serum cholesterol in the Norfolk population of the European prospective investigation into cancer (EPIC-Norfolk): Cross sectional study. Br. Med. J. 2001, 323, 1286–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aljuraiban, G.S.; Chan, Q.; Oude Griep, L.M.; Brown, I.J.; Daviglus, M.L.; Stamler, J.; Van Horn, L.; Elliott, P. The impact of eating frequency and time of intake on nutrient quality and body mass index: The INTERMAP Study, a population based study HHS Public Access. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Souza, R.V.; Sarmento, R.A.; de Almeida, J.C.; Canuto, R. The effect of shift work on eating habits: A systematic review. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2019, 45, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eicher-Miller, H.A.; Khanna, N.; Boushey, C.J.; Gelfand, S.B.; Delp, E.J. Temporal Dietary Patterns Derived among the Adult Participants of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2004 Are Associated with Diet Quality. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 116, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Overall | Male | Female | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 40.8 (9.1) | 41.9 (8.8) | 39.0 (9.4) | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.0 (4.1) | 27.7 (3.6) | 25.7 (4.6) | |

| Ethnicity | White | 7874 (97.3%) | 96.9% | 98.0% |

| Other | 203 (2.5%) | 2.9% | 1.9% | |

| Missing | 13 (0.2%) | 0.2% | 0.2% | |

| Region of employment | England | 5822 (72.0% | 70.5% | 74.3% |

| Scotland | 1333 (16.5%) | 18.4% | 13.3% | |

| Wales | 792 (9.8%) | 9.5% | 10.3% | |

| Missing | 143 (1.8%) | 1.6% | 2.1% | |

| Educational level | A levels/Higher or equivalent | 2599 (32.1%) | 32.0% | 32.4% |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 2222 (27.5%) | 27.5% | 30.2% | |

| Other | 3268 (40.4%) | 42.3% | 37.3% | |

| Missing | 1 (0%) | 0% | 0% | |

| Annual household income | Less than £37,999 | 2123 (26.2%) | 19.8% | 36.6% |

| £38,000 to £77,999 | 5162 (63.8%) | 70.4% | 53.1% | |

| More than £78,000 | 804 (9.9%) | 9.7% | 10.3% | |

| Missing | 1 (0%) | 0% | 0% | |

| Relationship status | Married/cohabitating | 6411 (79.2%) | 85.8% | 68.8% |

| Single | 876 (10.8%) | 6.5% | 17.9% | |

| Divorced/separated | 619 (7.7%) | 6.4% | 9.7% | |

| Other | 183 (2.3%) | 1.4% | 3.6% | |

| Missing | 1 (0%) | 0% | 0% | |

| Work hours | Less than/equal to 40 hours/week | 3766 (46.6%) | 36.3% | 63.0% |

| Greater than 40 hours/week | 4324 (53.4%) | 63.7% | 37.0% | |

| Missing | 1 (0%) | 0% | 0% | |

| Physical activity * | Low | 1561 (19.3%) | 17.3% | 22.4% |

| Moderate | 5593 (69.1%) | 70.4% | 67.0% | |

| High | 936 (11.6%) | 12.2% | 10.5% | |

| Missing | 1 (0%) | 0% | 0% | |

| Smoker status | Current | 634 (7.8%) | 6.6% | 9.8% |

| Former | 1874 (23.2%) | 23.3% | 22.9% | |

| Never | 5582 (69.0%) | 70.1% | 67.3% | |

| Missing | 1 (0%) | 0% | 0% | |

| Alcohol consumption | Yes | 7479 (92.4%) | 93.8% | 90.2% |

| No | 611 (7.6%) | 6.2% | 9.8% | |

| Missing | 0 (0%) | 0% | 0% | |

| Sleep duration | Less than 7 hours | 2563 (31.7%) | 34.4% | 27.3% |

| 7–8 hours | 5262 (65.0%) | 63.1% | 68.2% | |

| 9 hours or more | 264 (3.3%) | 2.5% | 4.5% | |

| Missing | 1 (0%) | 0% | 0% |

| Cluster 1: Saturated Fat Intake (%kcal *) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | Ptrend | |

| Mean (SD †) | 8 (1) | 11 (0) | 12 (0) | 15 (2) | |

| Interquartile Range | 3–9 | 10–11 | 12–13 | 14–30 | |

| Prevalent Cases/N | 478/1443 | 702/2054 | 822/2233 | 910/2360 | |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.01 (0.91; 1.11) | 1.06 (0.96; 1.17) | 1.06 (0.95; 1.17) | 0.27 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.01 (0.91; 1.11) | 1.05 (0.95; 1.16) | 1.05 (0.94; 1.16) | 0.37 |

| Cluster 2: Carbohydrate Intake (%kcal) | |||||

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | Ptrend | |

| Mean (SD) | 39 (4) | 46 (1) | 49 (1) | 56 (4) | |

| Interquartile Range | 10–43 | 44–47 | 48–51 | 52–76 | |

| Prevalent Cases/N | 851/1955 | 668/1804 | 665/1918 | 728/2413 | |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.88 (0.80; 0.95) | 0.85 (0.77; 0.92) | 0.79 (0.71; 0.86) | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.88 (0.81; 0.96) | 0.85 (0.78; 0.93) | 0.79 (0.71; 0.86) | <0.001 |

| Cluster 3: Protein Intake (%kcal) | |||||

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | Ptrend | |

| Mean (SD) | 13 (1) | 16 (0) | 17 (0) | 21 (3) | |

| Interquartile Range | 8–14 | 15–16 | 17–18 | 19–55 | |

| Prevalent Cases/N | 437/1344 | 771/2144 | 820/2162 | 884/2440 | |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.05 (0.95; 1.16) | 1.07 (0.97; 1.18) | 1.02 (0.91; 1.13) | 0.83 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.05 (0.95; 1.16) | 1.07 (0.97; 1.18) | 1.02 (0.91; 1.13) | 0.82 |

| Cluster 1: Saturated Fat Intake (%kcal *) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | Ptrend | |

| Mean (SD †) | 8 (1) | 11 (0) | 12 (0) | 15 (2) | |

| Interquartile Range | 3–9 | 10–11 | 12–13 | 14–30 | |

| Prevalent Cases/N | 478/1443 | 702/2054 | 822/2233 | 910/2360 | |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.99 (0.89; 1.10) | 1.02 (0.92; 1.13) | 1.01 (0.90; 1.12) | 0.87 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.99 (0.89; 1.10) | 1.02 (0.92; 1.13) | 1.00 (0.89; 1.12) | 0.95 |

| Cluster 2: Carbohydrate Intake (%kcal) | |||||

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | Ptrend | |

| Mean (SD) | 39 (4) | 46 (1) | 49 (1) | 56 (4) | |

| Interquartile Range | 10–43 | 44–47 | 48–51 | 52–76 | |

| Prevalent Cases/N | 851/1955 | 668/1804 | 665/1918 | 728/2413 | |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.93 (0.85; 1.01) | 0.93 (0.84; 1.01) | 0.89 (0.81; 0.98) | 0.02 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.93 (0.85; 1.01) | 0.92 (0.84; 1.01) | 0.89 (0.80; 0.98) | 0.01 |

| Cluster 2: Fiber Intake (g/1000 kcal) | |||||

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | Ptrend | |

| Mean (SD) | 6.32 (0.92) | 8.33 (0.48) | 10.09 (0.57) | 13.30 (2.09) | |

| Interquartile Range | 2.54—7.50 | 7.51—9.16 | 9.17—11.14 | 11.15—35.62 | |

| Prevalent Cases/N | 806/2020 | 757/2024 | 688/2019 | 661/2027 | |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.91 (0.84; 0.99) | 0.81 (0.73; 0.89) | 0.76 (0.68; 0.85) | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.92 (0.84; 1.00) | 0.82 (0.74; 0.90) | 0.78 (0.70; 0.86) | <0.001 |

| Cluster 3: Eating occasions/day | |||||

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | Ptrend | |

| Mean (SD) | 3.06 (0.35) | 3.8 (0.16) | 4.35 (0.16) | 5.17 (0.44) | |

| Interquartile Range | 1.71—3.43 | 3.57–4.00 | 4.14—4.57 | 4.71—7.71 | |

| Prevalent Cases/N | 649/1747 | 819/2150 | 755/2013 | 689/2162 | |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.99 (0.90; 1.08) | 0.94 (0.85; 1.03) | 0.76 (0.68; 0.85) | <0.001 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.99 (0.90; 1.08) | 0.94 (0.85; 1.04) | 0.76 (0.68; 0.86) | <0.001 |

| Cluster 3: Energy Intake (kcal) | |||||

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | Ptrend | |

| Mean (SD) | 1374.52 (174.91) | 1759.66 (85.25) | 2056.47 (91.38) | 2596.07 (330.91) | |

| Interquartile Range | 627.33—1603.69 | 1603.91—1906.23 | 1906.24—2227.87 | 2227.97—4620.40 | |

| Prevalent Cases/N | 678/2023 | 716/2022 | 763/2022 | 755/2023 | |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.96 (0.87; 1.06) | 0.96 (0.86; 1.06) | 0.95 (0.84; 1.07) | 0.49 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (ref) | 0.97 (0.88; 1.07) | 0.97 (0.87; 1.07) | 0.96 (0.85; 1.08) | 0.64 |

| Cluster 4: Protein Intake (%kcal) | |||||

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | Ptrend | |

| Mean (SD) | 13 (1) | 16 (0) | 17 (0) | 21 (3) | |

| Interquartile Range | 8–14 | 15–16 | 17–18 | 19–55 | |

| Prevalent Cases/N | 437/1344 | 771/2144 | 820/2162 | 884/2440 | |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.06 (0.96; 1.17) | 1.08 (0.97; 1.19) | 1.02 (0.91; 1.14) | 0.86 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.06 (0.96; 1.17) | 1.08 (0.97; 1.19) | 1.02 (0.91; 1.14) | 0.88 |

| Cluster 4: Carbohydrate Irregularity (%) | |||||

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | Ptrend | |

| Mean (SD) | 7 (2) | 11 (1) | 15 (1) | 23 (5) | |

| Interquartile Range | 0–9 | 10 -12 | 13–17 | 18–79 | |

| Prevalent Cases/N | 573/1706 | 621/1782 | 919/2520 | 799/2082 | |

| Model 1 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.01 (0.92; 1.12) | 1.05 (0.95; 1.14) | 1.04 (0.94; 1.14) | 0.39 |

| Model 2 | 1.00 (ref) | 1.01 (0.91; 1.11) | 1.05 (0.95; 1.14) | 1.03 (0.93; 1.14) | 0.43 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hunt, L.C.; Dashti, H.S.; Chan, Q.; Gibson, R.; Vetter, C. Quantifying Diet Intake and Its Association with Cardiometabolic Risk in the UK Airwave Health Monitoring Study: A Data-Driven Approach. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1170. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12041170

Hunt LC, Dashti HS, Chan Q, Gibson R, Vetter C. Quantifying Diet Intake and Its Association with Cardiometabolic Risk in the UK Airwave Health Monitoring Study: A Data-Driven Approach. Nutrients. 2020; 12(4):1170. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12041170

Chicago/Turabian StyleHunt, Larissa C., Hassan S. Dashti, Queenie Chan, Rachel Gibson, and Céline Vetter. 2020. "Quantifying Diet Intake and Its Association with Cardiometabolic Risk in the UK Airwave Health Monitoring Study: A Data-Driven Approach" Nutrients 12, no. 4: 1170. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12041170

APA StyleHunt, L. C., Dashti, H. S., Chan, Q., Gibson, R., & Vetter, C. (2020). Quantifying Diet Intake and Its Association with Cardiometabolic Risk in the UK Airwave Health Monitoring Study: A Data-Driven Approach. Nutrients, 12(4), 1170. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12041170