The Early Food Insecurity Impacts of COVID-19

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey Development and Recruitment

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

3.2. Food Insecurity Prevalence

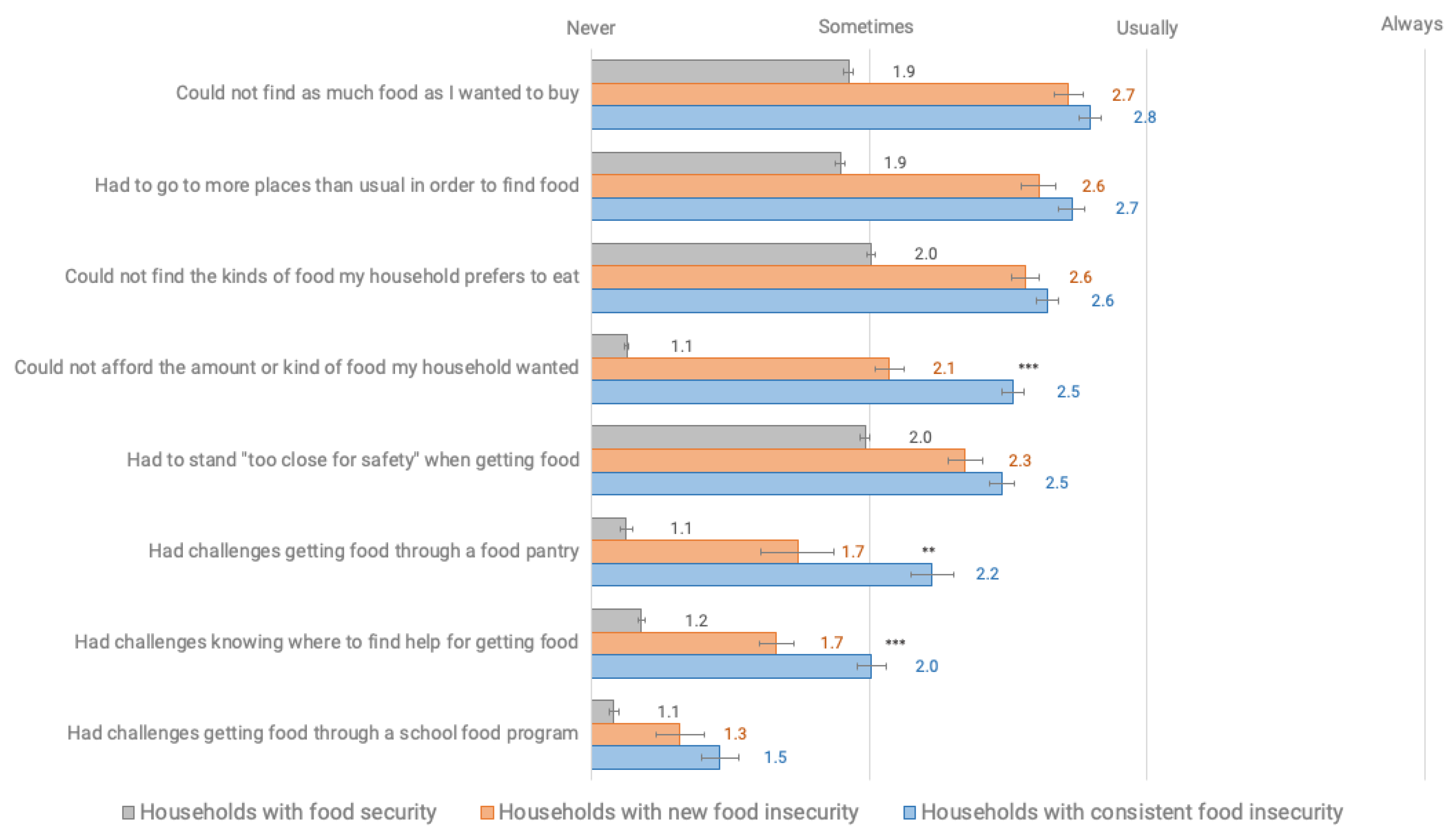

3.3. Food Access Challenges and Concerns

3.4. Coping Strategies

3.5. Desired Interventions

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Question | Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Food Insecure | Determined based on the responses to the U.S Household Food Security Survey Module: Six-Item Short Form. These households were food insecure during COVID-19, including newly food insecure and consistently food insecure households | Binary (1 = Food Insecure, 0 = Food Secure) |

| Newly Food Insecure | Determined based on the responses to the U.S Household Food Security Survey Module: Six-Item Short Form. These households were classified as not food insecure during the year prior to COVID-19, but were classified as food insecure since COVID-19. | Binary (1 = Newly Food Insecure, 0 = Food Secure) |

| Consistently Food Insecure | Determined based on the responses to the U.S Household Food Security Survey Module: Six-Item Short Form. These households were classified as food insecure both in the year prior to COVID-19 and since COVID-19. | Binary (1 = Consistently Food Insecure, 0 = Food Secure) |

| Food Secure | Determined based on the responses to the U.S Household Food Security Survey Module: Six-Item Short Form. These households were not classified as food insecure during COVID-19. | Binary (1 = Food Secure, 0 = Food Insecure) |

| Age | In what year were you born? (age determined by subtracting birth year from 2020) | Continuous |

| Household size | How many people in the following age groups currently live in your household (household defined as those currently living within your household, including family and non-family members)? | Number of people (07– + ) of household members in ages 0–17, 18–65, 65 + |

| Children | Whether respondent indicated any children in household size | Binary |

| Gender | Which of the following best describes your gender identity? | Binary (Female = 1, Male = 0) * |

| Race (White) | What is your race? Check all that apply. | Binary (White = 1, non-white = 0) |

| Education | What is the highest level of formal education that you have? | Some high school = 1; High school graduate = 2; Some college = 3; Associates degree/technical school/apprenticeship = 4; Bachelor’s degree = 5; Postgraduate/professional degree = 6 |

| College | Indication of a bachelor’s degree, postgraduate/professional degree in education | Binary (1 = College, No College = 0) |

| Income | Which of the following best describes your household income range in 2019 before taxes? | Less than $12,999 per year= 1; $13,000- $24,999 per year = 2; $25,000-$49,999 per year = 3; $50,000-$74,999 per year =4 $75,000- $99,999 per year = 5; $100,000- $124,99 per year = 6; $125,000-$149,999 = 7; More than $150,000 per year = 8 |

| Urban Met Area | ZIP code, determination of ZIP code within metropolitan Burlington three county area (Chittenden, Franklin, Grand Isle) | Binary (1 = Urban, Rural = 0) |

| Challenge Questions | Since the coronavirus outbreak (March 8th), how often did these happen to your household? | 1 = Never, 2 = Sometimes, 3 = Usually, 4 = Always, Not Applicable |

| Could not afford the amount or kind of food my household wanted to buy | ||

| Could not find as much food as I wanted to buy (e.g., food not in store) | ||

| Could not find the kinds of food my household prefers to eat | ||

| Delivered food to a friend, neighbor, or family member | ||

| Had challenges getting food through a food pantry | ||

| Had challenges getting food through a school food program | ||

| Had challenges knowing where to find help for getting food | ||

| Had to go to more places than usual in order to find the food my household wanted | ||

| Had to stand “too close for safety” to other people, when getting food (less than six feet) | ||

| Concern Questions | On a scale from 1 (not at all worried) to 6 (extremely worried), what is your level of worry for your household about the following as it relates to coronavirus. | 1= not at all worried, 6= extremely worried, not applicable |

| There will not be enough food in the store | ||

| Food will become more expensive for my household | ||

| Food will become unsafe | ||

| My household will lose access to programs that provide free food or money for food | ||

| My household will have a decrease in income and won’t be able to afford enough food | ||

| My household won’t have enough food if we have to stay at home and can’t go out at all | ||

| Current and Future Coping Strategies | Which of the following strategies, if any, are you currently using or likely to use in the future during the coronavirus if your household has challenges affording food? Indicate both current use where applicable and future use. | Yes = 1, No = 0 for current strategies; 1 = Very Unlikely, 2 = Unlikely, 3 = Somewhat Unlikely, 4 = Somewhat Likely, 5= Likely, 6= Very Likely for future strategies |

| Accept food from friends or family | ||

| Borrow money from friends or family | ||

| Buy different, cheaper foods | ||

| Buy food on credit | ||

| Buy foods that don’t go bad quickly (like pasta, beans, rice, canned foods) | ||

| Get food from a food pantry or soup kitchen | ||

| Sign up for or continue participation in a government program such as 3Squares VT or WIC or National School Lunch Program | ||

| Stretch the food that I have by eating less | ||

| Helpful Strategies | What, if anything, would make it easier for your household to meet its food needs during the coronavirus pandemic? | 1 = Not Helpful, 2 = Somewhat Helpful, 3 = Helpful, 4 = Very Helpful, Not Applicable |

| Access to public transit or rides | ||

| Different hours in meal programs or stores | ||

| Extra money to help pay for food or bills | ||

| Help with administrative problems (like applying for food assistance) | ||

| Increase benefits of existing food assistance programs (like SNAP or WIC) | ||

| Information about food assistance programs or food pantries | ||

| More (or different) food in stores | ||

| More trust in safety of food delivery | ||

| More trust in safety of going to stores | ||

| Support for the cost of food delivery |

| Characteristic * | Respondents (N = 3219) | Food Secure | Newly Food Insecure | Consistently Food Insecure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (range) – yr | 51.5 ± 15.6 (19–94) | 52.2 ± 15.7 (20–94) | 45.4 ± 14.0 (20–85) | 46.9 ± 14.2 (19–78) | |

| Household size (range) – no. | 2.7 ± 1.5 (1–12) | 2.6 ± 1.3 (1–12) | 3.2 ± 1.7 (1–12) | 2.9 ± 1.8 (1–11) | |

| Gender – no. (%) | Female | 2274 (79.4) | 1607 (78.0) | 199 (85.4) | 333 (81.6) |

| Male | 539 (18.8) | 424 (20.6) | 28 (12.0) | 59 (14.5) | |

| Non-binary | 22 (0.8) | 14 (0.6) | 2 (0.8) | 6 (1.5) | |

| Transgender | 13 (0.5) | 5 (0.2) | 2 (0.8) | 6 (1.5) | |

| Other (self describe) | 16 (0.6) | 10 (0.4) | 2 (0.8) | 4 (1.0) | |

| Race – no. (%) | White | 2669 (96.1) | 1939 (97.2) | 224 (96.0) | 366 (91.7) |

| Two or more races | 73 (2.6) | 40 (2.0) | 7 (3.0) | 21 (5.0) | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 18 (0.6) | 8 (0.4) | 0 (0.00) | 6 (1.5) | |

| Asian | 13 (0.5) | 6 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 4 (1.0) | |

| Black or African American | 5 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) | 1( 0.5) | 2 (0.5) | |

| Ethnicity – no. (%) | Not Hispanic or Latino | 2783 (98.4) | 2005 (98.5) | 97.8 (0.02) | 98.3 (0.02) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 45 (1.6) | 31 (1.5) | 5 (2.2) | 7 (1.7) | |

| Education level – no. (%) | Some high school (no diploma) | 11 (0.4) | 2 ( < 0.01) | 1 (0.4) | 6 (1.5) |

| High school graduate (incl. GED) | 260 (9.1) | 118 (5.7) | 34 (15.0) | 90 (22.1) | |

| Some college (no degree) | 423 (14.8) | 230 (11.1) | 48 (20.6) | 109 (26.8) | |

| Associates degree/technical school/apprenticeship | 301 (10.5) | 193 (9.4) | 25 (10.7) | 65 (16.0) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 962 (33.6) | 749 (36.3) | 76 (32.6) | 94 (23.1) | |

| Postgraduate/professional degree | 910 (31.7) | 771 (37.4) | 49 (21.0) | 43 (10.6) | |

| 2019 Household Income – no. (%) | Less than $12,999 per year | 167 (6.0) | 60 (3.0) | 21 (9.2) | 72 (17.7) |

| $13,000–$24,999 per year, | 332 (11.9) | 147 (7.3) | 37 (16.2) | 131 (32.2) | |

| $25,000–$49,999 per year, | 672 (24.0) | 433 (21.5) | 74 (32.5) | 133 (32.7) | |

| $50,000–$74,999 per year | 560 (20.0) | 426 (21.2) | 54 (23.7) | 49 (12.0) | |

| $75,000–$99,999 per year | 442 (15.8) | 376 (18.7) | 22 (9.6) | 12 (2.9) | |

| $100,000–$124,999 per year | 290 (10.4) | 257 (12.8) | 13 (5.7) | 7 (1.7) | |

| $125,000–$149,999 per year | 141 (5.0) | 126 (6.3) | 4 (1.8) | 1 (0.2) | |

| More than $150,000 per year | 193 (6.9) | 181 (9.0) | 3 (1.3) | 2 (0.4) | |

| ZIP Code within Census Metropolitan Statistical Area – no. (%) | Yes | 1149 (41.1) | 1156 (57.2) | 141 (62.4) | 247 (61.2) |

| No | 1649 (58.9) | 864 (42.8) | 85 (37.6) | 153 (38.3) | |

| Children in household – no. (%) | Yes | 913 (41.9) | 590 (37.7) | 118 (62.4) | 173 (53.6) |

| No | 1267 (58.1) | 975 (62.3) | 71 (37.6) | 150 (46.4) |

| Variable | n= | Mean | Std Error | Std. Dev. | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Insecure in Previous 12 months | 3086 | 0.188 | 0.007 | 0.390 | 0.174 | 0.197 |

| Food Insecure Since COVID-19 | 3028 | 0.248 | 0.008 | 0.432 | 0.233 | 0.259 |

| p < 0.001 | ||||||

| In the Year Prior to COVID-19 | Since COVID-19 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Aggregate Score * | Consistently Food Insecure | Consistently Food Insecure | Newly Food Insecure |

| 2 | 21.17% | 15.30% | 30.04% |

| 3 | 15.51% | 15.30% | 23.95% |

| 4 | 14.05% | 10.27% | 13.69% |

| 5 | 13.41% | 17.61% | 14.83% |

| 6 | 35.85% | 41.51% | 17.49% |

| Low Food Security | 50.73% | 40.87% | 67.68% |

| Very Low Food Security | 49.26% | 59.12% | 32.32% |

| Newly Food Insecure Respondents | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | Standard Error | P= | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Age | −0.010 | 0.008 | 0.235 | −0.025 | 0.006 |

| Race (white) | −0.415 | 0.456 | 0.363 | −1.310 | 0.479 |

| Job Loss | 1.423 | 0.249 | 0.000 | 0.935 | 1.910 |

| Furlough | 1.016 | 0.317 | 0.001 | 0.395 | 1.637 |

| Lost Hours | 0.802 | 0.244 | 0.001 | 0.323 | 1.281 |

| Female | 0.426 | 0.280 | 0.128 | −0.122 | 0.975 |

| Children | 0.981 | 0.209 | 0.000 | 0.571 | 1.391 |

| College Degree | −0.567 | 0.200 | 0.005 | −0.958 | −0.176 |

| Income | −0.398 | 0.068 | 0.000 | −0.531 | −0.265 |

| Urban Metro County | −0.134 | 0.199 | 0.499 | −0.523 | 0.255 |

| Consistently Food Insecure Respondents | |||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Standard Error | P= | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Age | −0.003 | 0.007 | 0.656 | −0.016 | 0.010 |

| Race (white) | −0.231 | 0.441 | 0.600 | −1.094 | 0.633 |

| Job Loss | 0.885 | 0.231 | 0.000 | 0.433 | 1.337 |

| Furlough | 1.075 | 0.264 | 0.000 | 0.558 | 1.591 |

| Lost Hours | 0.636 | 0.219 | 0.004 | 0.206 | 1.065 |

| Female | 0.337 | 0.239 | 0.160 | −0.133 | 0.806 |

| Children | 0.838 | 0.187 | 0.000 | 0.472 | 1.204 |

| College Degree | −1.224 | 0.176 | 0.000 | −1.568 | −0.879 |

| Income | −0.760 | 0.070 | 0.000 | −0.897 | −0.622 |

| Urban Metro County | 0.136 | 0.177 | 0.443 | −0.212 | 0.484 |

| Food Secure | Newly Food Insecure | Consistently Food Insecure | P Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Situation | Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | All Groups | New and Consistently Food Insecure |

| Could not afford the amount or kind of food my household wanted to buy | 1.13 | 1.11–1.14 | 2.07 | 1.97–2.18 | 2.52 | 2.44–2.60 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Could not find as much food as I wanted to buy (e.g., food not in store) | 1.92 | 1.89 = 1.96 | 2.72 | 2.61–2.82 | 2.79 | 2.71–2.88 | <0.001 | 0.246 |

| Could not find the kinds of food my household prefers to eat | 2.01 | 1.97–2.04 | 2.56 | 2.47–2.66 | 2.64 | 2.56–2.72 | <0.001 | 0.232 |

| Had challenges getting food through a food pantry | 1.12 | 1.08–1.17 | 1.74 | 1.48–2.00 | 2.23 | 2.08–2.38 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| Had challenges getting food through a school food program | 1.08 | 1.04–1.11 | 1.32 | 1.15–1.49 | 1.46 | 1.33–1.59 | <0.001 | 0.081 |

| Had challenges knowing where to find help for getting food | 1.18 | 1.15–1.20 | 1.66 | 1.54–1.79 | 2.01 | 1.91–2.11 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Had to go to more places than usual in order to find the food my household wanted | 1.89 | 1.86–1.93 | 2.61 | 2.49–2.73 | 2.73 | 2.64–2.82 | <0.001 | 0.123 |

| Had to stand “too close for safety” to other people, when getting food (less than six feet) | 1.99 | 1.95–2.02 | 2.34 | 2.22–2.47 | 2.48 | 2.39–2.57 | <0.001 | 0.096 |

| Food Secure | Newly Food Insecure | Consistently Food Insecure | P Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question | Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | All Groups | New and Consistently Food Insecure |

| There will not be enough food in the store | 2.95 | 2.89–3.00 | 4.07 | 3.90–4.24 | 4.35 | 4.23–4.48 | <0.001 | 0.007 |

| Food will become more expensive for my household | 3.22 | 3.16- 3.29 | 4.74 | 4.59–4.90 | 5.23 | 5.13–5.32 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Food will become unsafe | 3.02 | 2.95–3.08 | 4.14 | 3.95–4.34 | 4.13 | 3.98–4.28 | <0.001 | 0.960 |

| My household will lose access to programs that provide free food or money for food | 1.69 | 1.59–1.79 | 3.23 | 2.91–3.56 | 4.39 | 4.19–4.59 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| My household will have a decrease in income and won’t be able to afford enough food | 2.57 | 2.50–2.65 | 4.61 | 4.42–4.79 | 4.98 | 4.84–5.11 | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| My household won’t have enough food if we have to stay at home and can’t go out at all | 3.02 | 2.95–3.09 | 4.64 | 4.45–4.82 | 4.90 | 4.77–5.04 | <0.001 | 0.010 |

| Food Secure | Newly Food Insecure | Consistently Food Insecure | P Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy | Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | All Groups | New and Consistently Food Insecure |

| Accept food from friends or family | 0.18 | 0.16–0.20 | 0.35 | 0.29–0.41 | 0.44 | 0.39–0.48 | <0.001 | 0.031 |

| Borrow money from friends or family | 0.03 | 0.03–0.04 | 0.14 | 0.10–0.19 | 0.24 | 0.20–0.28 | <0.001 | 0.004 |

| Buy different, cheaper foods | 0.29 | 0.27–0.31 | 0.64 | 0.58–0.70 | 0.67 | 0.62–0.71 | <0.001 | 0.559 |

| Buy food on credit | 0.11 | 0.10–0.13 | 0.25 | 0.20–0.31 | 0.27 | 0.23–0.32 | <0.001 | 0.613 |

| Buy foods that don’t go bad quickly (like pasta, beans, rice, canned foods) | 0.62 | 0.60–0.64 | 0.77 | 0.72–0.82 | 0.76 | 0.72–0.80 | <0.001 | 0.813 |

| Get food from a food pantry or soup kitchen | 0.02 | 0.02–0.03 | 0.10 | 0.06–0.13 | 0.27 | 0.23–0.31 | <0.001 | 0.000 |

| Sign up for or continue participation in a government program such as 3Squares VT or WIC or National School Lunch Program | 0.08 | 0.06–0.09 | 0.29 | 0.23–0.35 | 0.41 | 0.36–0.45 | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| Stretch the food that I have by eating less | 0.15 | 0.14–0.17 | 0.64 | 0.58–0.71 | 0.68 | 0.64–0.73 | <0.001 | 0.360 |

| Newly Food Insecure | Consistently Food Insecure | P Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Program | Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | |

| Meals on Wheels | 0.01 | 0.00–0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01–0.04 | 0.207 |

| SNAP | 0.11 | 0.08–0.15 | 0.28 | 0.23–0.31 | <0.001 |

| WIC | 0.11 | 0.07–0.14 | 0.12 | 0.09–0.14 | 0.815 |

| Food Pantry | 0.08 | 0.04–0.11 | 0.21 | 0.17–0.25 | <0.001 |

| Food Secure | Newly Food Insecure | Consistently Food Insecure | P Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy | Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | All Groups | New and Consistently Food Insecure |

| Accept food from friends or family | 2.76 | 2.69–2.83 | 3.45 | 3.25–3.66 | 3.69 | 3.53–3.85 | <0.0001 | 0.045 |

| Borrow money from friends or family | 1.97 | 1.91–2.03 | 2.78 | 2.57–2.99 | 2.78 | 2.60–2.95 | <0.0001 | 0.666 |

| Buy different, cheaper foods | 3.80 | 3.72–3.87 | 4.80 | 4.64–4.96 | 4.86 | 4.72–4.99 | <0.0001 | 0.189 |

| Buy food on credit | 2.45 | 2.37–2.52 | 3.18 | 2.94–3.42 | 3.09 | 2.89–3.29 | <0.0001 | 0.425 |

| Buy foods that don’t go bad quickly (like pasta, beans, rice, canned foods) | 4.90 | 4.84–4.96 | 5.20 | 5.06–5.34 | 5.19 | 5.07–5.31 | <0.0001 | 0.495 |

| Get food from a food pantry or soup kitchen | 1.75 | 1.70–1.81 | 2.86 | 2.66–3.06 | 3.57 | 3.39–3.76 | <0.0001 | 0.000 |

| Sign up for or continue participation in a government program such as 3Squares VT or WIC or National School Lunch Program | 1.90 | 1.84–1.97 | 3.24 | 2.97–3.50 | 4.10 | 3.90–4.29 | <0.0001 | 0.000 |

| Stretch the food that I have by eating less | 2.99 | 2.92–3.07 | 4.68 | 4.52–4.85 | 4.93 | 4.80–5.05 | <0.0001 | 0.007 |

| Food Secure | Newly Food Insecure | Consistently Food Insecure | P Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strategy | Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | All Groups | New and Consistently Food Insecure |

| Access to public transit or rides | 1.20 | 1.16–1.24 | 1.25 | 1.12–1.37 | 1.80 | 1.64–19.6 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Different hours in meal programs or stores | 1.79 | 1.74–1.85 | 2.04 | 1.87–2.20 | 2.22 | 2.10–2.35 | <0.001 | 0.101 |

| Extra money to help pay for food or bills | 2.35 | 2.29–2.42 | 3.30 | 3.18–3.42 | 3.68 | 3.62–3.74 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Help with administrative problems (like applying for food assistance) | 1.41 | 1.34–1.48 | 2.16 | 1.95–2.37 | 2.58 | 2.44–2.73 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| Increase benefits of existing food assistance programs (like SNAP or WIC) | 1.80 | 1.71–1.89 | 2.88 | 2.67–3.08 | 3.51 | 3.40–3.61 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Information about food assistance programs or food pantries | 1.60 | 1.53–1.68 | 2.35 | 2.16–2.53 | 2.77 | 2.65–2.89 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| More (or different) food in stores | 2.77 | 2.73–2.82 | 3.20 | 3.09–3.31 | 3.27 | 3.18–3.36 | <0.001 | 0.172 |

| More trust in safety of food delivery | 2.78 | 2.73–2.84 | 3.14 | 3.00–3.27 | 3.20 | 3.10–3.30 | <0.001 | 0.369 |

| More trust in safety of going to stores | 3.23 | 3.19–3.27 | 3.53 | 3.43–3.62 | 3.49 | 3.41–3.56 | <0.001 | 0.762 |

| Support for the cost of food delivery | 2.33 | 2.26–2.40 | 3.09 | 2.95–3.23 | 3.26 | 3.15–3.36 | <0.001 | 0.015 |

References

- Koo, J.R.; Cook, A.R.; Park, M.; Sun, Y.; Sun, H.; Lim, J.T.; Tam, C.; Dickens, B.L. Interventions to mitigate early spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Singapore: A modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. An Introduction to the Basic Concepts of Food Security; United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman-Jensen, A.; Rabbitt, M.P.; Gregory, C.; Singh, A. Household Food Security in the United States in 2018; US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; ISBN 9781634846592. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, S.P.; Haddix, A.; Barnett, K. Incremental health care costs associated with food insecurity and chronic conditions among older adults. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2018, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Berkowitz, S.A.; Basu, S.; Meigs, J.B.; Seligman, H.K. Food Insecurity and Health Care Expenditures in the United States, 2011–2013. Health Serv. Res. 2018, 53, 1600–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gundersen, C.; Ziliak, J.P. Food insecurity and health outcomes. Health Aff. 2015, 34, 1830–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gundersen, C.; Tarasuk, V.; Cheng, J.; de Oliveira, C.; Kurdyak, P. Food insecurity status and mortality among adults in Ontario, Canada. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0202642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasuk, V.; Cheng, J.; de Oliveira, C.; Dachner, N.; Gundersen, C.; Kurdyak, P. Association between household food insecurity and annual health care costs. CMAJ 2015, 187, 1031–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berkowitz, S.A.; Seligman, H.K.; Meigs, J.B.; Basu, S. Food insecurity, healthcare utilization, and high cost: A longitudinal cohort study. Am. J. Manag. Care 2018, 24, 399–404. [Google Scholar]

- Nord, M.; Coleman-Jensen, A.; Gregory, C. Prevalence of US Food Insecurity Is Related to Changes in Unemployment, Inflation, and the Price of Food; United States Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Kim, Y.; Birkenmaier, J. Unemployment and household food hardship in the economic recession. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United States Department of Labor. The Employment Situation-April 2020; United States Department of Labor: Washington DC, USA, 2020.

- Hake, M.; Engelhard, E.; Dewey, A.; Gundersen, C. The Impact of the Coronavirus on Child Food Insecurity; Feeding America: Chicago, IL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, S. COVID-19 forces recalibration of priorities as world embraces new habits. Nielsen, 20 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pantries Padded with Produce as North Americans Prepare for the COVID-19 Long Haul. 17 April 2020. Available online: https://www.nielsen.com/us/en/insights/article/2020/pantries-padded-with-produce-as-north-americans-prepare-for-the-covid-19-long-haul/ (accessed on 13 July 2020).

- Wolfson, J.A.; Leung, C.W. Food Insecurity and COVID-19: Disparities in Early Effects for US Adults. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US Census Bureau. Urban and Rural; US Census Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 2010.

- Niles, M.T.; Neff, R.; Biehl, E.; Bertmann, F.; Morgan, E.; Wentworth, T. Food Access and Security During Coronavirus Survey- Version 1.0. Harvard Dataverse V2 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engard, N.C. LimeSurvey http://limesurvey.org. Public Serv. Q. 2009, 5, 272–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.A. A Meta-Analysis of Cronbach’s Coefficient Alpha. J. Consum. Res. 1994, 21, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Front Porch Forum Paid Campaign Posting. Available online: https://frontporchforum.com/advertise-on-fpf/paid-campaign-posting (accessed on 8 May 2020).

- United States Census Bureau. CP05: Comparative Demographic Estimates. Available online: data.census.gov (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- USDA Economic Research Service. U.S. Household Food Security Survey Module: Six-Item Short Form 2012. Available online: https://www.ers.usda.gov/media/8282/short2012.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2020).

- StataCorp Stata Statistical Software: Release 15 2017; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2017.

- United States Census Bureau. CP03: Comparative Economic Characteristics. Available online: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?g=0400000US50&d=ACS5-YearEstimatesComparisonProfiles&text=education&tid=ACSCP5Y2018.CP03&hidePreview=false&cid=CP02_2009_2013_001E&vintage=2018 (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- United States Census Bureau. CP02: Comparative Social Characteristics in the United States. Available online: https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?g=0400000US50&d=ACS5-YearEstimatesComparisonProfiles&text=education&tid=ACSCP5Y2018.CP02&hidePreview=false&cid=CP02_2009_2013_001E&vintage=2018 (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Private Label Manufacturer’s Association. Today’s Primary Shopper. 2013. Available online: https://plma.com/2013PLMA_GfK_Study.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2020).

- Pew Research Center. About Half of Lower-Income Americans Report Household Job or Wage Loss Due to Covid-19. 2020. Available online: https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2020/04/21/about-half-of-lower-income-americans-report-household-job-or-wage-loss-due-to-covid-19/ (accessed on 13 July 2020).

- Bauer, L. The COVID-19 Crisis Has Already Left Too Many Children Hungry in America. Brookings Institute. 2020. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/05/06/the-covid-19-crisis-has-already-left-too-many-children-hungry-in-america/ (accessed on 13 July 2020).

- Fitzpatrick, K.M.; Harris, C.; Drawve, G. Assessing U.S. Food Insecurity in the United States during COVID-19 Pandemic. 2020. Available online: https://fulbright.uark.edu/departments/sociology/research-centers/community-family-institute/_resources/community-and-family-institute/revised-assessing-food-insecurity-brief.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2020).

- Ridberg, R.A.; Bell, J.F.; Merritt, K.E.; Harris, D.M.; Young, H.M.; Tancredi, D.J. A Pediatric Fruit and Vegetable Prescription Program Increases Food Security in Low-Income Households. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019, 51, 224–230.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bryce, R.; Guajardo, C.; Ilarraza, D.; Milgrom, N.; Pike, D.; Savoie, K.; Valbuena, F.; Miller-Matero, L.R. Participation in a farmers’ market fruit and vegetable prescription program at a federally qualified health center improves hemoglobin A1C in low income uncontrolled diabetics. Prev. Med. Reports 2017, 7, 176–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althoff, R.R.; Ametti, M.; Bertmann, F. The role of food insecurity in developmental psychopathology. Prev. Med. (Baltim.) 2016, 92, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanson, K.L.; Connor, L.M. Food insecurity and dietary quality in US adults and children: A systematic review. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryu, J.-H.; Bartfeld, J.S. Household food insecurity during childhood and subsequent health status: The early childhood longitudinal study—Kindergarten cohort. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, e50–e55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hager, E.R.; Quigg, A.M.; Black, M.M.; Coleman, S.M.; Heeren, T.; Rose-Jacobs, R.; Cook, J.T.; de Cuba, S.A.E.; Casey, P.H.; Chilton, M.; et al. Development and Validity of a 2-Item Screen to Identify Families at Risk for Food Insecurity. Pediatrics 2010, 126, e26–e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, S.; Malinak, D.; Chang, J.; Perez, M.; Perez, S.; Settlecowski, E.; Rodriggs, T.; Hsu, M.; Abrew, A.; Aedo, S. Implementation of a food insecurity screening and referral program in student-run free clinics in San Diego, California. Prev. Med. Reports 2017, 5, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottino, C.J.; Rhodes, E.T.; Kreatsoulas, C.; Cox, J.E.; Fleegler, E.W. Food Insecurity Screening in Pediatric Primary Care: Can Offering Referrals Help Identify Families in Need? Acad. Pediatr. 2017, 17, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinard, C.A.; Bertmann, F.M.W.; Byker Shanks, C.; Schober, D.J.; Smith, T.M.; Carpenter, L.C.; Yaroch, A.L. What Factors Influence SNAP Participation? Literature Reflecting Enrollment in Food Assistance Programs From a Social and Behavioral Science Perspective. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2017, 12, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, L. Why do low-income women not use food stamps? Findings from the California Women’s Health Survey. Public Health Nutr. 2008, 11, 1288–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Morton, L.W.; Bitto, E.A.; Oakland, M.J.; Sand, M. Accessing food resources: Rural and urban patterns of giving and getting food. Agric. Human Values 2008, 25, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mammen, S.; Bauer, J.W.; Richards, L. Understanding Persistent Food Insecurity: A Paradox of Place and Circumstance. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 92, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feeding America. Map the Meal Gap 2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.feedingamerica.org/sites/default/files/2019-04/2017-map-the-meal-gap-technical-brief.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2020).

- WCAX. People Stocking Up on Toilet Paper; Shelves Empty. 2020. Available online: https://www.wcax.com/content/news/People-stocking-up-on-568696561.html (accessed on 13 July 2020).

| Characteristic * | Respondents (N = 3219) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (range) – yr | 51.5 ± 15.6 (19 to 94) | |

| Household size (range) – no. | 2.7 ± 1.5 (1 to 12) | |

| Gender – no. (%) | Female | 2274 (79.4) |

| Male | 539 (18.8) | |

| Non-binary | 22 (0.8) | |

| Transgender | 13 (0.5) | |

| Other (self describe) | 16 (0.6) | |

| Race – no. (%) | White | 2669 (96.1) |

| Two or more races | 73 (2.6) | |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 18 (0.6) | |

| Asian | 13 (0.5) | |

| Black or African American | 5 (0.2) | |

| Ethnicity – no. (%) | Not Hispanic or Latino | 2783 (98.4) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 45 (1.6) | |

| Education level – no. (%) | Some high school (no diploma) | 11 (0.4) |

| High school graduate (incl. GED) | 260 (9.1) | |

| Some college (no degree) | 423 (14.8) | |

| Associates degree/technical school/apprenticeship | 301 (10.5) | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 962 (33.6) | |

| Postgraduate/professional degree | 910 (31.7) | |

| 2019 Household Income – no. (%) | Less than $12,999 per year | 167 (6.0) |

| $13,000–$24,999 per year, | 332 (11.9) | |

| $25,000–$49,999 per year, | 672 (24.0) | |

| $50,000–$74,999 per year | 560 (20.0) | |

| $75,000–$99,999 per year | 442 (15.8) | |

| $100,000–$124,999 per year | 290 (10.4) | |

| $125,000–$149,999 per year | 141 (5.0) | |

| More than $150,000 per year | 193 (6.9) | |

| ZIP Code within Census Metropolitan Statistical Area – no. (%) | Yes | 1149 (41.1) |

| No | 1649 (58.9) | |

| Children in household – no. (%) | Yes | 913 (41.9) |

| No | 1267 (58.1) |

| Variable | Odds Ratio | Standard Error | P= | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.995 | 0.006 | 0.350 | 0.983 | 1.006 |

| Race (white) | 0.731 | 0.267 | 0.392 | 0.358 | 1.496 |

| Job Loss | 3.064 | 0.586 | 0.000 | 2.107 | 4.457 |

| Furlough | 2.885 | 0.649 | 0.000 | 1.856 | 4.485 |

| Lost Hours | 2.053 | 0.368 | 0.000 | 1.446 | 2.916 |

| Female | 1.422 | 0.283 | 0.077 | 0.963 | 2.100 |

| Children | 2.459 | 0.379 | 0.000 | 1.818 | 3.325 |

| College Degree | 0.380 | 0.055 | 0.000 | 0.286 | 0.506 |

| Income | 0.556 | 0.030 | 0.000 | 0.501 | 0.618 |

| Urban Metro County | 1.024 | 0.151 | 0.871 | 0.767 | 1.368 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niles, M.T.; Bertmann, F.; Belarmino, E.H.; Wentworth, T.; Biehl, E.; Neff, R. The Early Food Insecurity Impacts of COVID-19. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2096. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12072096

Niles MT, Bertmann F, Belarmino EH, Wentworth T, Biehl E, Neff R. The Early Food Insecurity Impacts of COVID-19. Nutrients. 2020; 12(7):2096. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12072096

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiles, Meredith T., Farryl Bertmann, Emily H. Belarmino, Thomas Wentworth, Erin Biehl, and Roni Neff. 2020. "The Early Food Insecurity Impacts of COVID-19" Nutrients 12, no. 7: 2096. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12072096

APA StyleNiles, M. T., Bertmann, F., Belarmino, E. H., Wentworth, T., Biehl, E., & Neff, R. (2020). The Early Food Insecurity Impacts of COVID-19. Nutrients, 12(7), 2096. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12072096