The Landscape of COVID-19 Vaccination in Zimbabwe: A Narrative Review and Analysis of the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats of the Programme

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

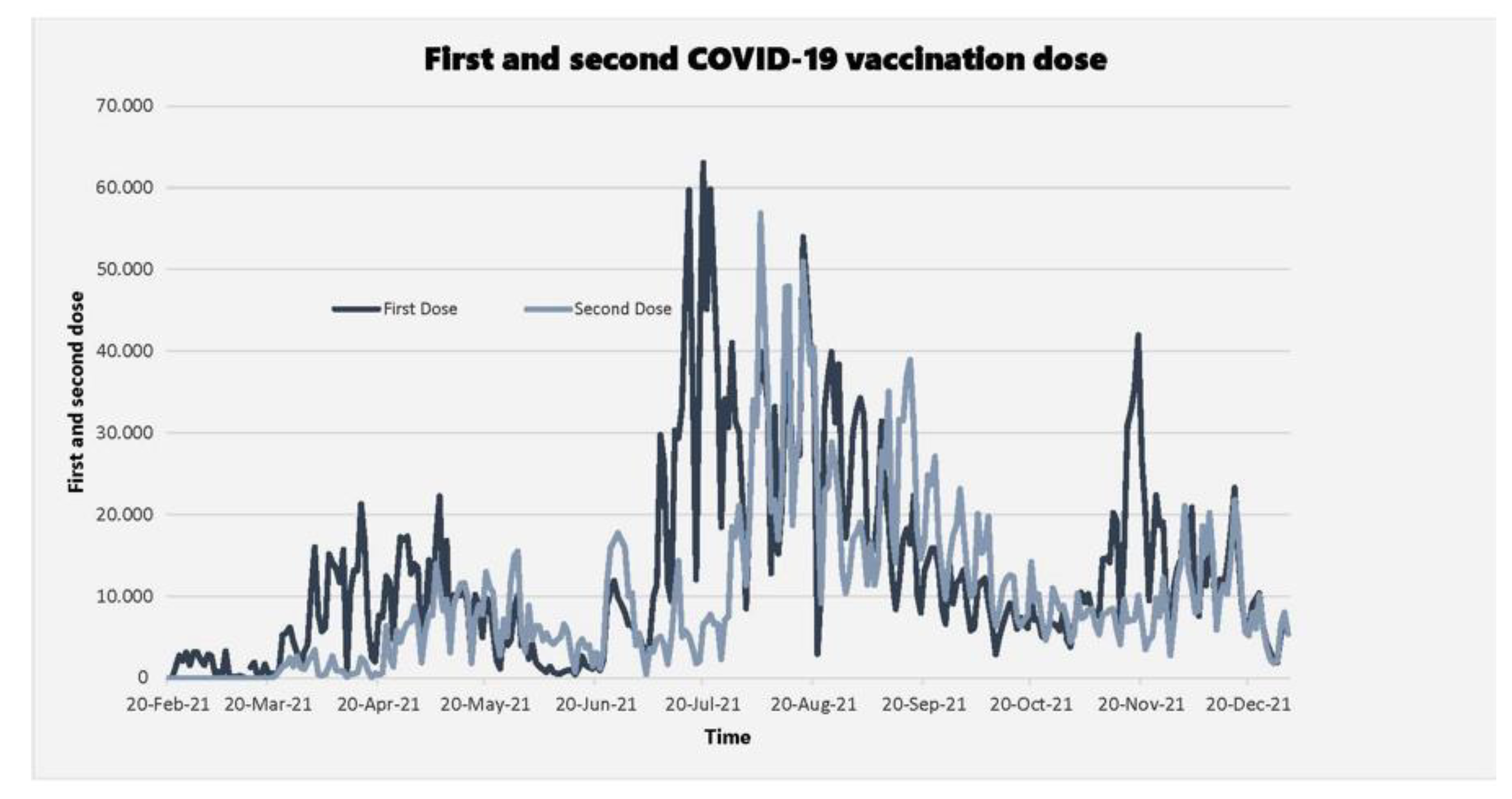

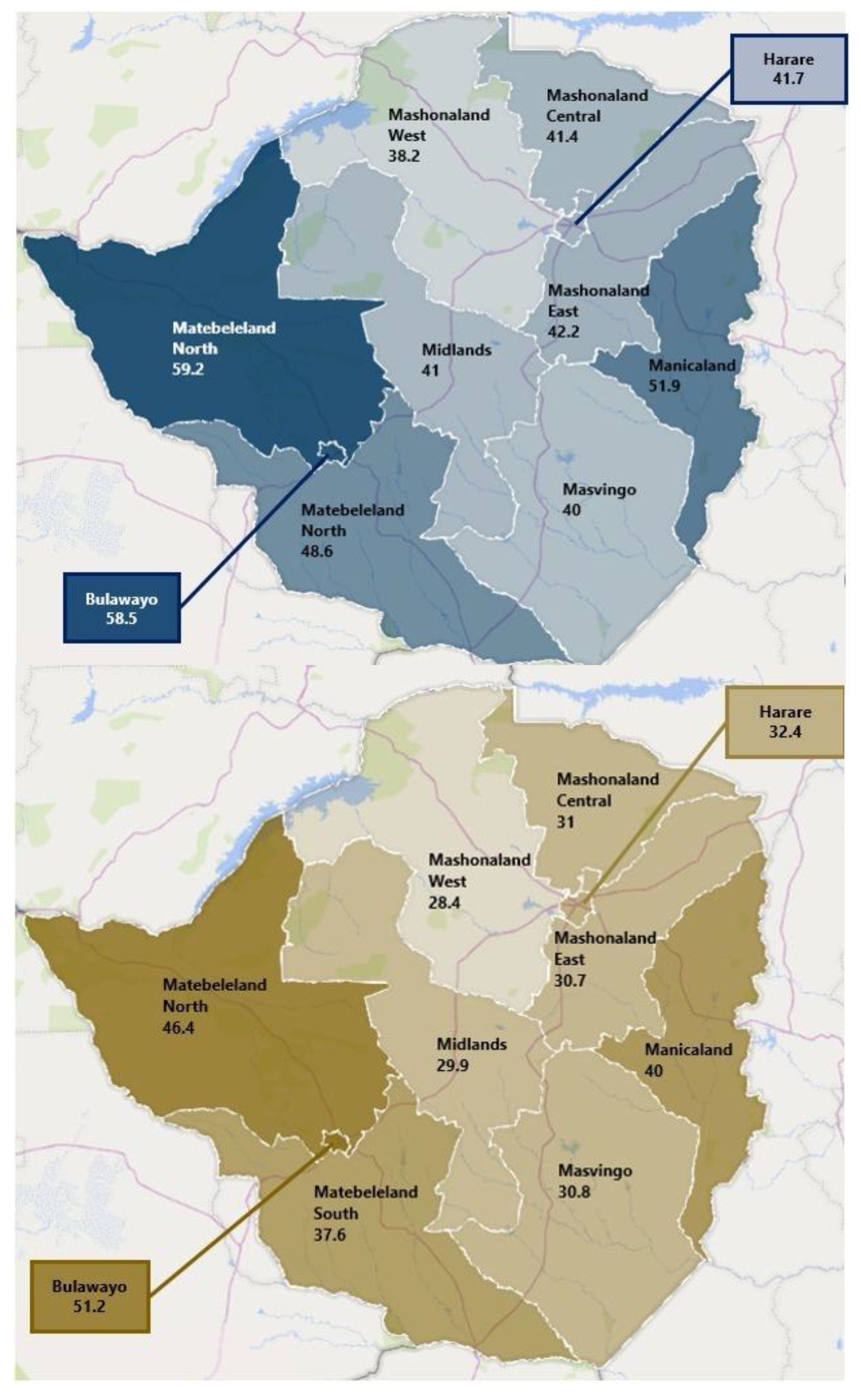

3. Findings

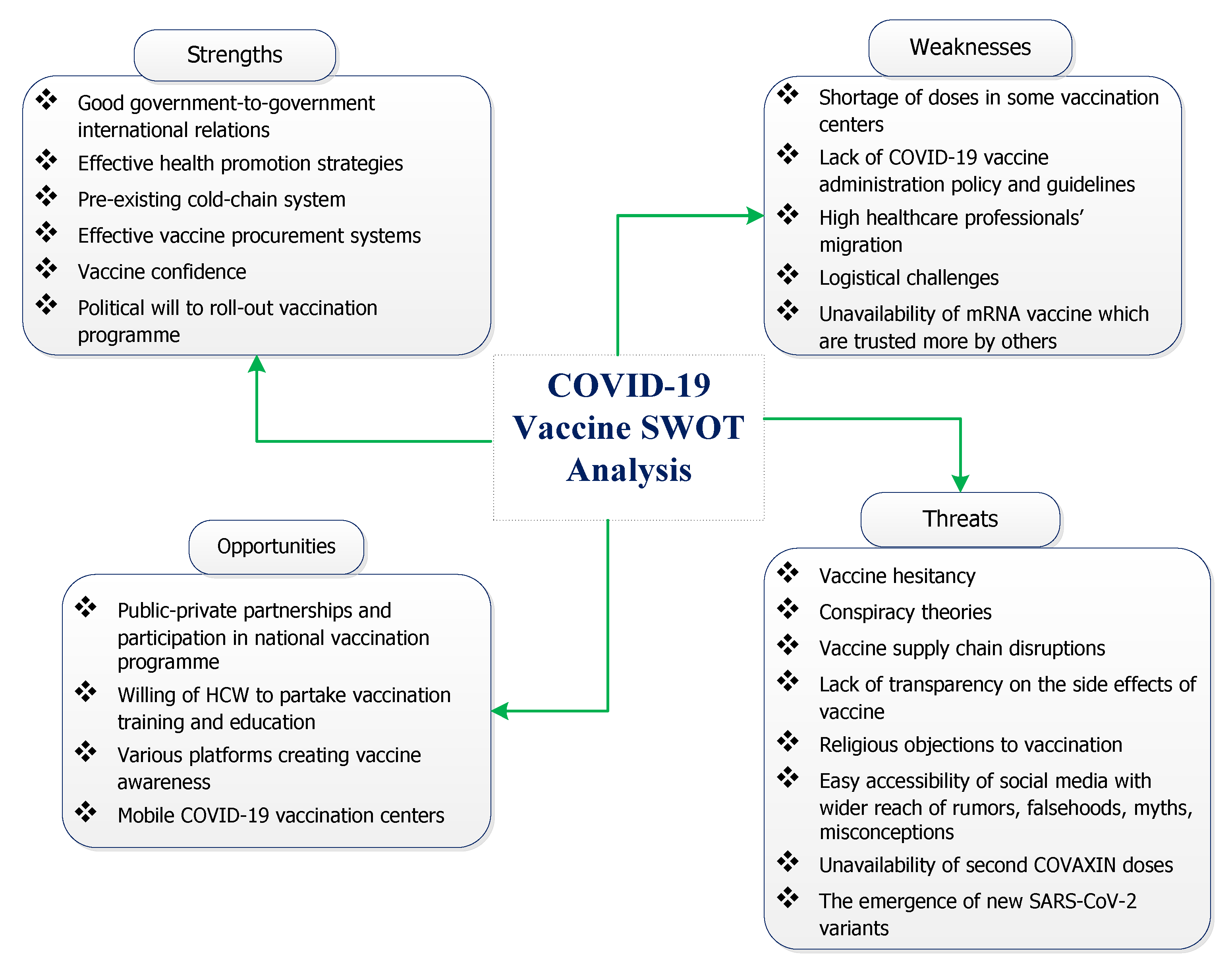

3.1. Strengths

3.2. Weaknesses

3.3. Opportunities

3.4. Threats

4. Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. WHO Issues Its First Emergency Use Validation for a COVID-19 Vaccine and Emphasizes need for Equitable Global Access. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/31-12-2020-who-issues-its-first-emergency-use-validation-for-a-covid-19-vaccine-and-emphasizes-need-for-equitable-global-access (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Extance, A. mRNA vaccines: Hope beneath the hype. bmj 2021, 375, n2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Call to Action: Vaccine Equity. Available online: https://www.who.int/campaigns/vaccine-equity/vaccine-equity-declaration (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Kreier, F. ‘Unprecedented achievement’: Who received the first billion COVID vaccinations? Nature 2021, 29, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkengasong, J.N.; Ndembi, N.; Tshangela, A.; Raji, T. COVID-19 Vaccines: How to Ensure Africa has Access. Nature 2020, 586, 197–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loembé, M.M.; Nkengasong, J.N. COVID-19 vaccine access in Africa: Global distribution, vaccine platforms, and challenges ahead. Immunity 2021, 54, 1353–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzinamarira, T.; Nachipo, B.; Phiri, B.; Musuka, G. COVID-19 vaccine roll-out in South Africa and Zimbabwe: Urgent need to address community preparedness, fears and hesitancy. Vaccines 2021, 9, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomberg. Zimbabwe Approves J & J Vaccines as COVID-19 Cases Climb. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-07-28/zimbabwe-approves-j-j-vaccines-as-covid-19-cases-climb (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- WHO. WHO Lists Additional COVID-19 Vaccine for Emergency Use and Issues Interim Policy Recommendations. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/07-05-2021-who-lists-additional-covid-19-vaccine-for-emergency-use-and-issues-interim-policy-recommendations (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Dzinamarira, T.; Murewanhema, G.; Musuka, G. Different SARS-CoV-2 variants, same prevention strategies. Public Health Pract. 2022, 3, 100223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, S.; Ishak, A.; Perez-Fernandez, J.; Garcia, E.; León-Figueroa, D.A.; Romaní, L.; Bonilla-Aldana, D.K.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J. Highly mutated SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant sparks significant concern among global experts–What is known so far? Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 45, 102234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/ (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Nachega, J.B.; Sam-Agudu, N.A.; Masekela, R.; van der Zalm, M.M.; Nsanzimana, S.; Condo, J.; Ntoumi, F.; Rabie, H.; Kruger, M.; Wiysonge, C.S. Addressing challenges to rolling out COVID-19 vaccines in African countries. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e746–e748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maketo, J.P.; Mutizwa, B. Dynamics and Trends in Vaccine Procurement and Distribution in Zimbabwe. Int. J. Humanit. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2021, 4, 62–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshili, N. Fronterliners Celebrate Vaccination. Available online: https://www.chronicle.co.zw/frontliners-celebrate-vaccination/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Murewanhema, G.; Burukai, T.V.; Chireka, B.; Kunonga, E. Implementing national COVID-19 vaccination programmes in sub-Saharan Africa- early lessons from Zimbabwe: A descriptive cross-sectional study. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2021, 40, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigevenga, R. Commentary on the Zimbabwean People’s Response towards the Anticipated COVID-19 Vaccine. J. Biomed. Res. Environ. Sci. 2021, 2, 174–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAbee, L.; Tapera, O.; Kanyangarara, M. Factors Associated with COVID-19 Vaccine Intentions in Eastern Zimbabwe: A Cross-Sectional Study. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MoHCC. Teenagers Now Eligible for Vaccination. Available online: http://www.mohcc.gov.zw/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=403:teenagers-now-eligible-for-vaccination&catid=84&Itemid=435 (accessed on 28 January 2022).

- Mundagowa, P.T.; Tozivepi, S.N.; Chiyaka, E.T.; Mukora-Mutseyekwa, F.; Makurumidze, R. Assessment of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among Zimbabweans: A rapid national survey. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machingaidze, S.; Wiysonge, C.S.; Hussey, G.D. Strengthening the expanded programme on immunization in Africa: Looking beyond 2015. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vaccinate or Resign, Zimbabwe Tells Government Workers. Available online: https://www.africanews.com/2021/09/08/vaccinate-or-resign-zimbabwe-tells-government-workers// (accessed on 28 January 2022).

- Musuka, G.; Mapingure, M.; Dzinamarira, T. Zimbabwe’s COVID-19 vaccination roll-out: Urgent need to rethink strategies to improve the supply chain. South Afr. Med. J. 2021, 111, 816. [Google Scholar]

- Africa News. Zimbabweans Desperate to Get Jabs, Amid Shortage. Available online: https://www.africanews.com/2021/07/13/zimbabweans-desperate-to-get-jabs-amid-shortage// (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Murewanhema, G.; Dzinamarira, T.; Herrera, H.; Musuka, G. COVID-19 vaccination for pregnant women in Zimbabwe: A public health challenge that needs an urgent discourse. Public Health Pract. 2021, 2, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matambo, R. Global Vaccine Politics and Its Impact on Africa—The Case of Zimbabwe. Available online: https://www.accord.org.za/analysis/global-vaccine-politics-and-its-impact-on-africa-the-case-of-zimbabwe/ (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Dzinamarira, T.; Musuka, G. Brain drain: An ever-present; significant challenge to the Zimbabwean public health sector. Public Health Pract. 2021, 2, 100086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murewanhema, G.; Mukwenha, S.; Dzinamarira, T.; Mukandavire, Z.; Cuadros, D.; Madziva, R.; Chingombe, I.; Mapingure, M.; Herrera, H.; Musuka, G. Optimising COVID-19 Vaccination Policy to Mitigate SARS-CoV-2 Transmission within Schools in Zimbabwe. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MoHCC. Greenlight for Private Sector COVID 19 Vaccine Procurement. Available online: http://www.mohcc.gov.zw/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=356:greenlight-for-private-sector-covid-19-vaccine-procurement&catid=84&Itemid=435 (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- Murewanhema, G. Vaccination hesitancy among women of reproductive age in resource-challenged settings: A cause for public health concern. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2021, 38, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afolabi, A.A.; Ilesanmi, O.S. Dealing with vaccine hesitancy in Africa: The prospective COVID-19 vaccine context. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2021, 38, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Kamal, A.-H.M.; Kabir, A.; Southern, D.L.; Khan, S.H.; Hasan, S.M.; Sarkar, T.; Sharmin, S.; Das, S.; Roy, T. COVID-19 vaccine rumors and conspiracy theories: The need for cognitive inoculation against misinformation to improve vaccine adherence. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiysonge, C.S.; Ndwandwe, D.; Ryan, J.; Jaca, A.; Batouré, O.; Anya, B.-P.M.; Cooper, S. Vaccine hesitancy in the era of COVID-19: Could lessons from the past help in divining the future? Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2021, 17, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, S.; van Rooyen, H.; Wiysonge, C.S. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in South Africa: How can we maximize uptake of COVID-19 vaccines? Expert Rev. Vaccines 2021, 20, 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- New Zimbabwe. Daily Metro. Masvingo Health Worker Dies After Receiving Chinese Vaccine. 5 March 2021. Available online: https://www.newzimbabwe.com/masvingo-health-worker-dies-after-receiving-chinese-vaccine/ (accessed on 7 October 2021).

- Murewanhema, G.; Mutsigiri-Murewanhema, F. Drivers of the third wave of COVID-19 in Zimbabwe and challenges for control: Perspectives and recommendations. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2021, 40, 46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yadegari, I.; Omidi, M.; Smith, S.R. The herd-immunity threshold must be updated for multi-vaccine strategies and multiple variants. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.P.; Day, T.; Arino, J.; Colijn, C.; Dushoff, J.; Li, M.; Mechai, S.; Van Domselaar, G.; Wu, J.; Earn, D.J. The origins and potential future of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern in the evolving COVID-19 pandemic. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, R918–R929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzinamarira, T.; Mukwenha, S.; Mukandavire, Z.; Cuadros, D.F.; Murewanhema, G.; Madziva, R.; Musuka, G. Insights from Zimbabwe’s SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e1624–e1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruxvoort, K.J.; Sy, L.S.; Qian, L.; Ackerson, B.K.; Luo, Y.; Lee, G.S.; Tian, Y.; Florea, A.; Aragones, M.; Tubert, J.E. Effectiveness of mRNA-1273 against delta, mu, and other emerging variants of SARS-CoV-2: Test negative case-control study. bmj 2021, 375, e068848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Three Sinovac Doses Fail to Protect Against Omicron in Study. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-12-23/three-sinovac-doses-fail-to-protect-against-omicron-study-shows (accessed on 29 January 2022).

- WHO. Report of the SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Available online: https://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/october/1_Report_WORKING_GROUP_vaccine_hesitancy_final.pdf (accessed on 31 December 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Murewanhema, G.; Musuka, G.; Denhere, K.; Chingombe, I.; Mapingure, M.P.; Dzinamarira, T. The Landscape of COVID-19 Vaccination in Zimbabwe: A Narrative Review and Analysis of the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats of the Programme. Vaccines 2022, 10, 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10020262

Murewanhema G, Musuka G, Denhere K, Chingombe I, Mapingure MP, Dzinamarira T. The Landscape of COVID-19 Vaccination in Zimbabwe: A Narrative Review and Analysis of the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats of the Programme. Vaccines. 2022; 10(2):262. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10020262

Chicago/Turabian StyleMurewanhema, Grant, Godfrey Musuka, Knowledge Denhere, Innocent Chingombe, Munyaradzi Paul Mapingure, and Tafadzwa Dzinamarira. 2022. "The Landscape of COVID-19 Vaccination in Zimbabwe: A Narrative Review and Analysis of the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats of the Programme" Vaccines 10, no. 2: 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10020262

APA StyleMurewanhema, G., Musuka, G., Denhere, K., Chingombe, I., Mapingure, M. P., & Dzinamarira, T. (2022). The Landscape of COVID-19 Vaccination in Zimbabwe: A Narrative Review and Analysis of the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats of the Programme. Vaccines, 10(2), 262. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines10020262