13C-NMR Data of Diterpenes Isolated from Aristolochia Species

Abstract

:Introduction

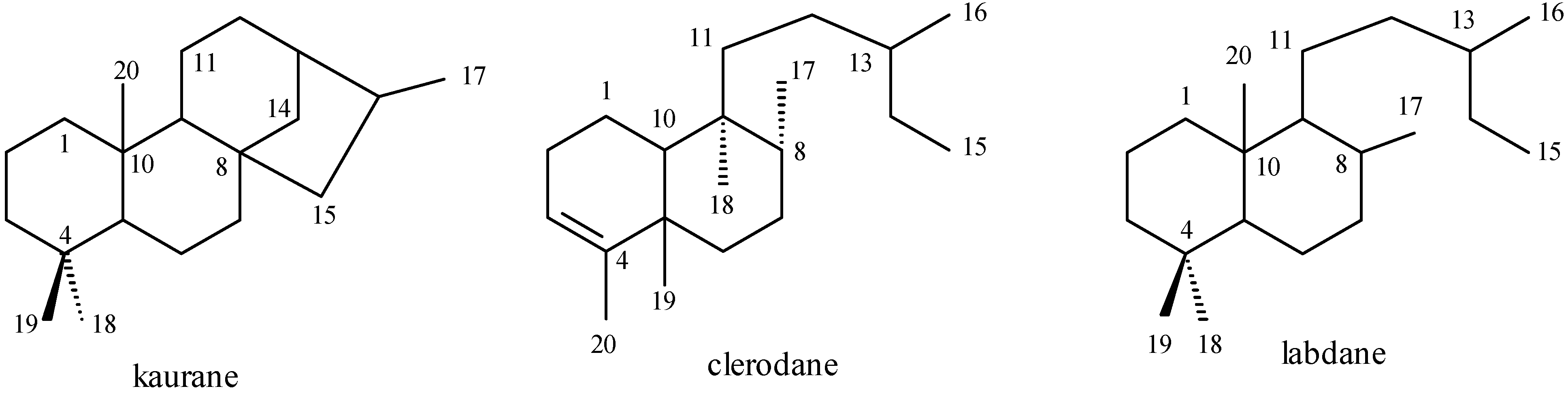

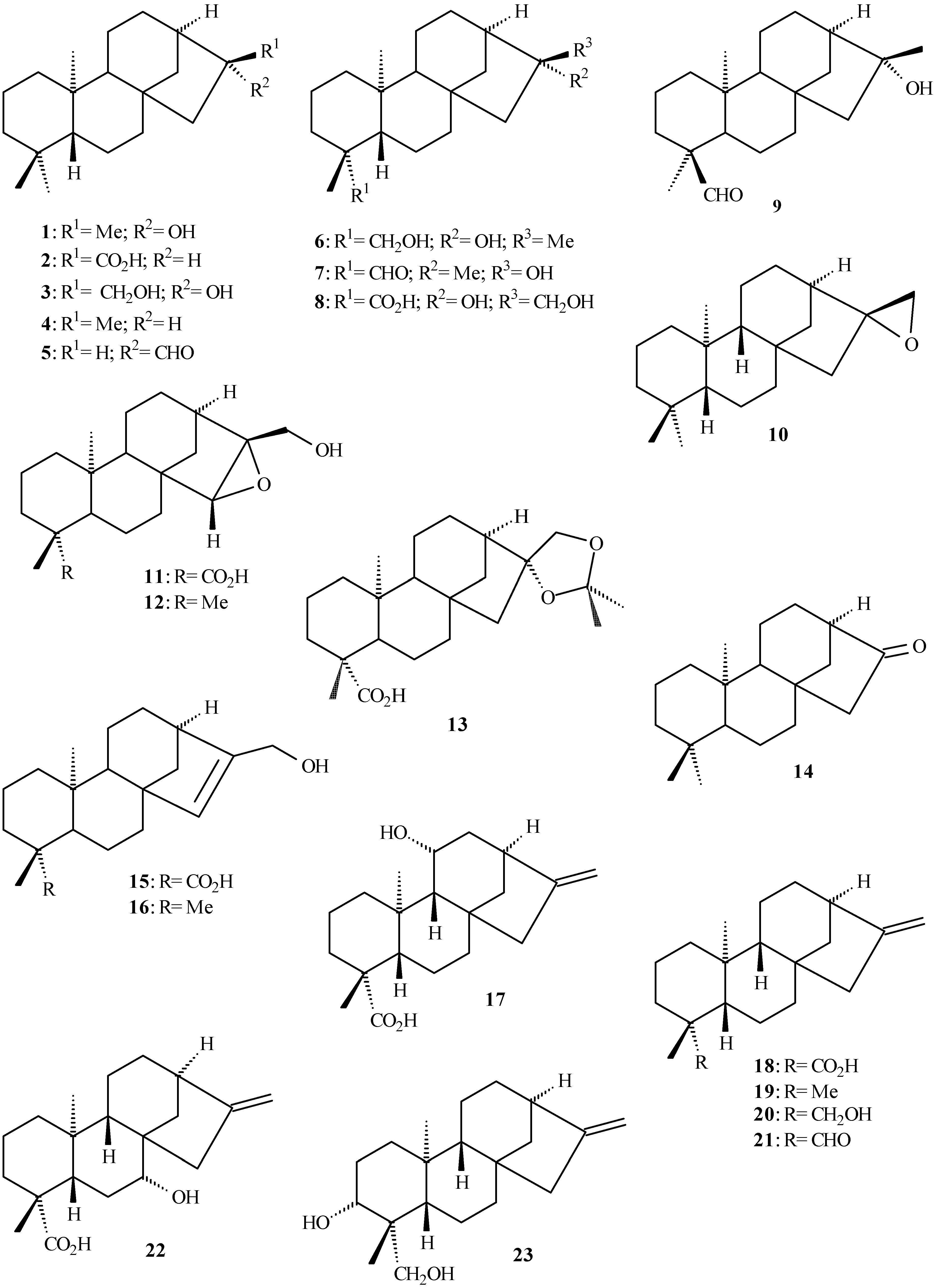

Kaurane derivates isolated from Aristolochia species

| Clerodane | Species |

|---|---|

| ent-Kauran-16β-ol [(–)-kauranol] (1) | A. rodriguesii [28] |

| ent-16β(H)-Kauran-17-oic acid (2) | A. elegans [7]; A. triangularis [13] |

| ent-Kauran-16β,17-diol (3) | A. elegans [7]; A. pubescens [31]; A. triangularis [13] |

| ent-16β(H)-Kaurane (4) | A. elegans [7]; A. triangularis [13] |

| ent-16α(H)-Kauran-17-al (5) | A. elegans [7] |

| ent-Kauran-16β,19-diol [ent-16β,19-dihydroxykaurane] (6) | A. rodriguesii [28] |

| ent-16α-Hydroxy-kauran-19-al [16a-hydroxy-(–)-kauran-19-al] (7) | A. rodriguesii [28]; A. triangularis [32] |

| ent-16β,17-Dihydroxy-(–)-kauran-19-oic acid (8) | A. rodriguesii [28] |

| ent-16β-Hydroxy-kauran-18-al [(–)-kauran-16α-hydroxy-18-al] (9) | A. triangularis [26] |

| ent-16β,17-Epoxykaurane (10) | A. elegans [7]; A. triangularis [32] |

| ent-15β,16β-Epoxy-17-hydroxy-kauran-19-oic acid (11) | A. rodriguesii [28] |

| ent-15β,16β-Epoxykauran-17-ol (12) | A. triangularis [13] |

| ent-16β,17-Isopropylidenedioxy-(–)-19-oic acid (13) | A. rodriguesii [28] |

| 17-nor-(–)-Kauran-16-one (14) | A. triangularis [13] |

| ent-17-Hydroxy-kaur-15-en-19-oic acid (15) | A. rodriguesii [28] |

| ent-Kaur-15-en-17-ol (16) | A. elegans [7]; A. pubescens [31]; A. triangularis [13,32] |

| ent-11β-Hydroxy-kaur-16-en-19-oic acid [(–)-11-hydroxy-kaur-16-en-19-oic acid] (17) | A. anguicida [33] |

| ent-Kaur-16-en-19-oic acid [kaurenic acid] (18) | A. anguicida [33]; A. rodriguesii [28]; A. triangularis [13] |

| (–)-ent-Kaur-16-ene (19) | A. triangularis [13,32] |

| (–)-ent-Kaur-16-en-19-ol (20) | A. triangularis [13,32] |

| (–)-ent-Kaur-16-en-19-al (21) | A. triangularis [13,32] |

| ent-7β-Hydroxy-kaur-16-en-19-oic acid (22) | A. anguicida [34] |

| ent-Kaur-16-en-3β,19-diol [ent-3β,18-dihydroxykaur-16-ene] (23) | A. rodriguesii [28] |

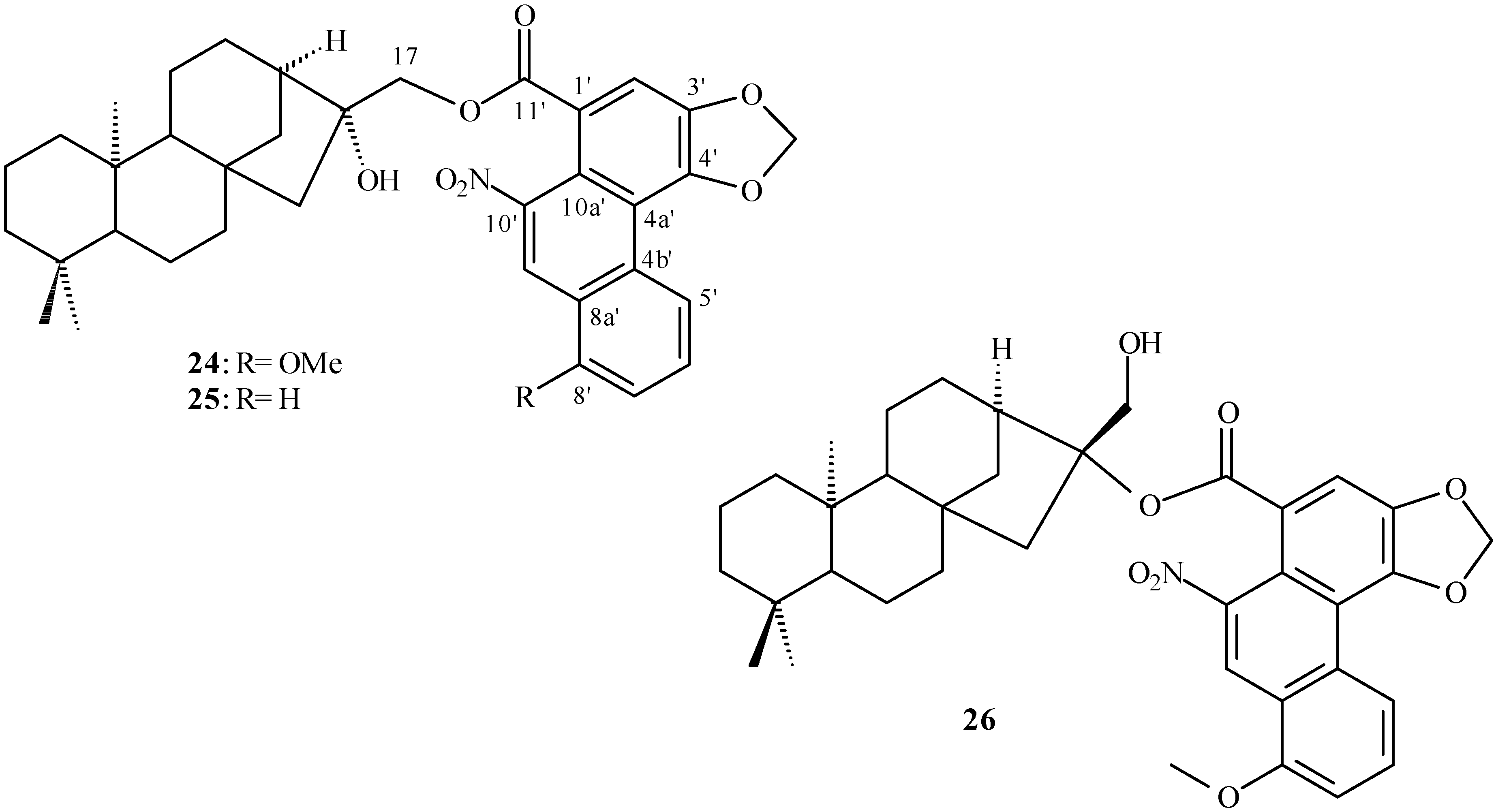

| ent-16β-Hydroxy-17-kauranyl aristolachate I [aristoloin I] (24) | A. elegans [4] |

| ent-16β-Hydroxy-17-kauranyl aristolachate II [aristoloin II] (25) | A. pubescens [31] |

| ent-17-Hydroxy-16β-kauranyl aristolachate I [aristolin] (26) | A. elegans [4] |

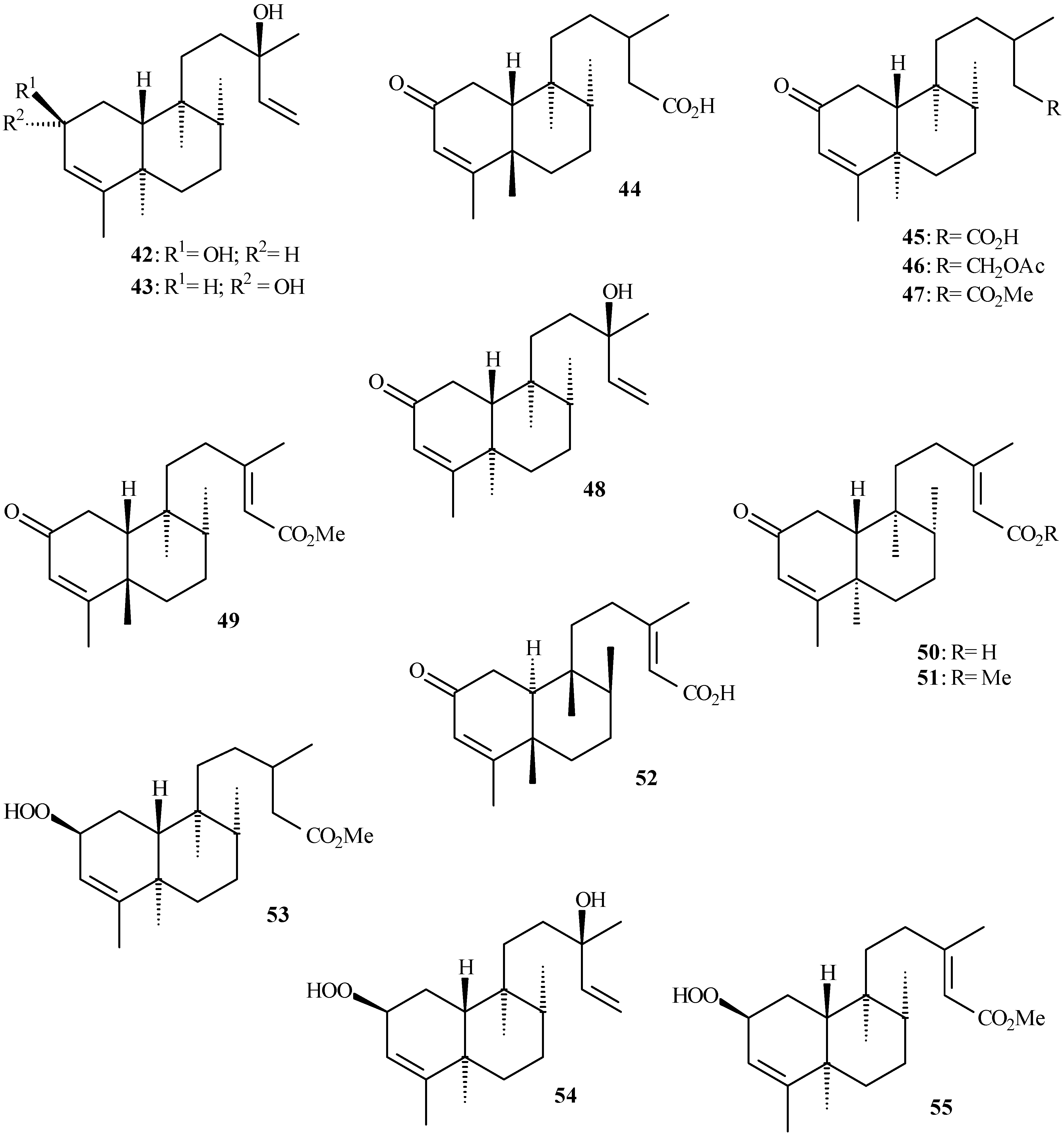

Clerodane derivatives isolated from Aristolochia species

| Clerodane | Species |

| (5R,8R,9S,10R)-ent-3-Cleroden-15-oic acid [13,14-dihydrokolavenic acid; populifolic acid] (27) | A. brasilienses [38]; A. cymbifera [39]; A. galeata [40] |

| (5R,8R,9S,10R)-ent-3-Cleroden-15-ol [dihydrokolavenol] (28) | A. galeata [40] |

| (5R,8R,9S,10R)-ent-15-Ethanoyl-3-clerodene [dihydrokolavenol acetate] (29) | A. galeata [40] |

| Methyl (5R,8R,9S,10R)-ent-3-cleroden-15-oate [methyl populifoloate]) (30) | A. esperanzae [38]; A. galeata [40] |

| (5S,8R,9S,10R)-ent-3-Cleroden-15-oic acid [epi-populifolic acid] (31) | A. cymbifera [39] |

| Methyl (5S,8R,9S,10R)-ent-3-cleroden-15-oate (32) | A. cymbifera [39] |

| (5R,8R,9S,10R)-ent-Clerod-3,13-dien-15-oic acid [Δ13,14-kolavenic acid] (33) | A. brasilienses [38]; A. galeata [40] |

| (5R,8R,9S,10R)-ent-Clerod-3,13-dien-15-ol [Δ13,14-kolavenol] (34) | A. galeata [40] |

| (5R,8R,9S,10R)-ent-15-Ethanoyl-clerod-3,13-diene [acetyl kolavenoate] (35) | A. galeata [40] |

| Methyl (5R,8R,9S,10R)-ent-clerod-3,13-dien-15-oate [methyl kolavenoate] (36) | A. esperanzae [38]; A. galeata [40] |

| (5S,8R,9S,10R)-ent-Clerod-3,13-dien-15-oic acid (37) | A. brasilienses [38] |

| (5R,8R,9S,10R)-ent-Clerod-3,14-dien-13β-ol [(+)-kolavelool] (38) | A. galeata [40] |

| (5R,8R,9S,10R)-(4→2)-abeo-Clerod-13β-hydroxy-2,14-dien-3-oic acid [(+)-(4®2)-abeo-kolavelool-3-oic acid] (39) | A. chamissonis [41] |

| (5R,8R,9S,10R)-ent-Clerod-14-en-3β,4α,13α-triol [(–)-3α,4β-dihydroxykolavelool] (40) | A. chamissonis [41] |

| (5R,8R,9S,10R)-ent-Clerod-3,14-dien-13α-ol [(–)-kolavelool] (41) | A. chamissonis [41]; A. cymbifera [38]; A. galeata [38] |

| (5R,8R,9S,10R)-ent-Clerod-3,14-dien-2α,13α-diol [(–)-2β-hydroxykolavelool] (42) | A. chamissonis [41] |

| (5R,8R,9S,10R)-ent-Clerod-3,14-dien-2β,13α-diol [(+)-13-epi-2α-hydroxykolavelool; 13-epi-roseostachenol] (43) | A. chamissonis [41] |

| (5S,8R,9S,10R)-2-Oxo-ent-3-cleroden-15-oic acid (44) | A. brasilienses [38] |

| (5R,8R,9S,10R)-2-Oxo-ent-3-cleroden-15-oic acid [2-oxopopulifolic acid] (45) | A. brasilienses [39]; A. cymbifera [39]; A. galeata [40] |

| (5R,8R,9S,10R)-2-Oxo-ent-15-ethanoyl-3-clerodene [2-oxodihydrokolavenol acetate] (46) | A. galeata [40] |

| Methyl (5R,8R,9S,10R)-2-oxo-ent-3-cleroden-15-oate [methyl 2-oxopopulifoloate] (47) | A. esperanzae [38] |

| (5R,8R,9S,10R)-2-Oxo-ent-clerod-3,14-dien-13α-ol [(–)-13-epi-2-oxokolavelool; 13-epi-roseostachenone] (48) | A. chamissonis [41] |

| Methyl (5S,8R,9S,10R)-2-oxo-ent-clerod-3,13-dien-15-oate (49) | A. brasilienses [38] |

| (5R,8R,9S,10R)-2-Oxo-ent-clerod 3,13-dien-15-oic acid [Δ13,14-2-oxokolavenic acid] (50) | A. brasilienses [38] |

| Methyl (5R,8R,9S,10R)-2-oxo-ent-clerod-3,13-dien-15-oate [methyl Δ13,14-2-oxokolavenoate] (51) | A. esperanzae [38] |

| (5S,8S,9R,10S)-2-Oxo-ent-clerod-3,13-dien-15-oic acid (52) | A. brasilienses [38] |

| Methyl (5R,8R,9S,10R)-ent-2α-hydroperoxy-3-cleroden-15-oate (53) | A. esperanzae [38] |

| (5R,8R,9S,10R)-ent-2α-Hydroperoxy-clerod-3,14-dien-13α-ol [(–)-2β-hydroperoxykolavelool] (54) | A. chamissonis [41] |

| Methyl (5R,8R,9S,10R)-ent-2α-hydroperoxy-clerod-3,13-dien-15-oate (55) | A. esperanzae [38] |

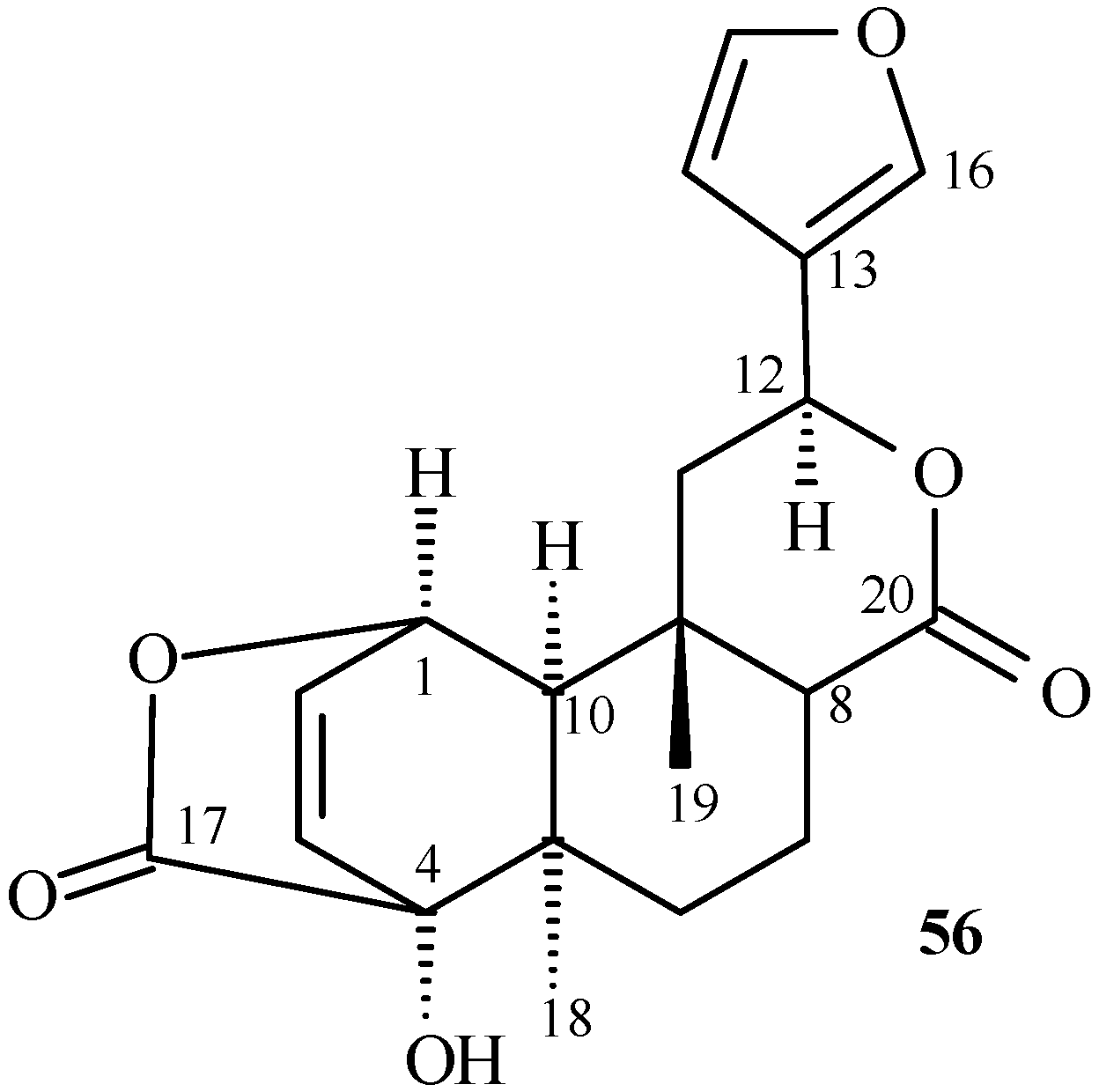

Furanoditerpene isolated from Aristolochia species

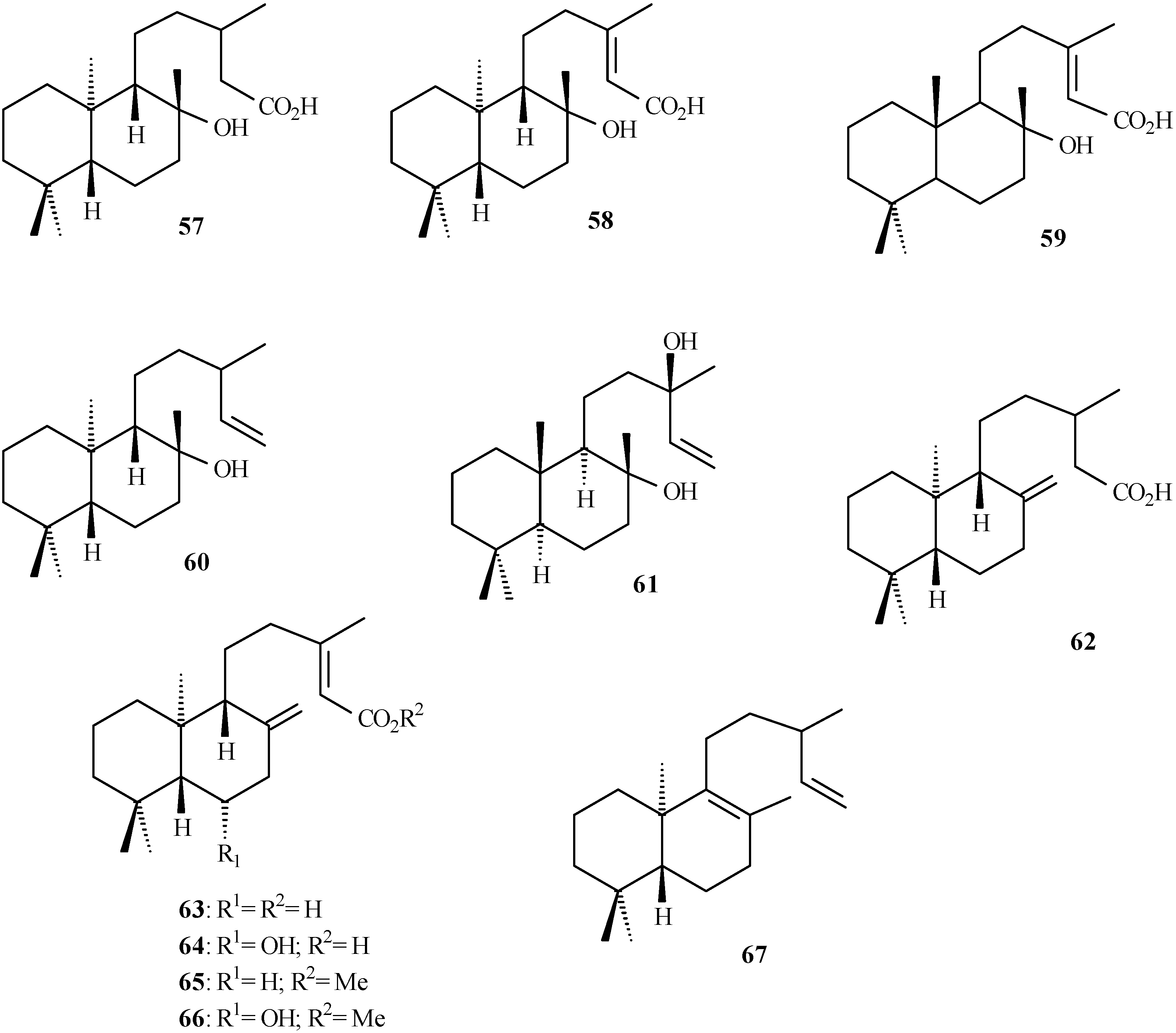

Labdane derivatives isolated from Aristolochia species

| Clerodane | Species |

| (5R,8R,9S,10S)-ent-Labdan-8β-hydroxy-15-oic acid (57) | A. galeata [40] |

| (5R,8R,9S,10S)-ent-Labd-13-en-8β-hydroxy-15-oic acid [Δ13,14-ent-labd-8β-ol-15-oic acid] (58) | A. galeata [40] |

| (5R,8R,9S,10S)-ent-Labd-14-en-8β-ol (60) | A. cymbifera [40] |

| (5S,8R,9R,10R)-ent-Labd-14-en-8β,13α-diol (61) | not isolated from Aristolochia species [54] |

| (5R,9S,10S)-ent-Labd-8(17)-en-15-oic acid (62) | A. ringens [55] |

| (5R,9S,10S)-ent-Labd-8(17),13-dien-15-oic acid [copalic acid] (63) | A. esperanzae [40]; A. galeata [40] |

| (5R,9S,10S)-ent-Labd-6β-hydroxy-8(17),13-dien-15-oic acid (64) | A. esperanzae [40] |

| Methyl (5R,8R,9S,10S)-ent-labd-8(17),13-dien-15-oate [methyl copalate] (65) | A. esperanzae [40] |

| Methyl (5R,9S,10S)-ent-labd-6β-hydroxy-8(17),13-dien-15-oate (66) | A. esperanzae [40] |

| (5R,10S)-ent-Labd-8,14-diene (67) | A. cymbifera [40] |

13C-NMR data of diterpenes

| Carbon | Compound / δC (in ppm) | ||||||||||||||

| 1 [56] | 2 [13] | 3 [31] | 4 [13] | 6 [28] | 8 [57,58] | 10 [59] | 11 [28] | 12 [13] | 13 [28] | 14 [56] | 15 [28] | 16 [13] | 17 [33] | 18 [33] | |

| 1 | 42.0 | 39.2 | 40.3 | 40.9 | 40.35 | 41.1 | 40.4 | 39.82 | 40.4 | 40.66 | 41.0 | 40.73 | 42.0 | 39.10 | 41.13 |

| 2 | 18.6 | 18.2 | 18.6 | 18.6 | 17.97a | 19.8 | 18.6 | 18.39a | 18.7 | 19.06 | 18.5 | 19.05a | 18.6 | 20.07 | 19.52 |

| 3 | 42.0 | 42.0 | 41.9 | 42.0 | 35.55 | 38.7 | 42.0 | 34.33 | 42.1 | 38.39 | 41.9 | 38.03 | 43.8 | 35.00 | 38.23 |

| 4 | 33.2 | 33.1 | 33.2 | 33.6 | 38.50 | 43.9 | 33.2 | 48.47 | 33.3 | 43.66 | 33.2 | 43.55 | 33.2 | 43.60 | 44.66 |

| 5 | 56.2 | 56.1a | 56.2 | 56.1a | 56.90b | 57.0 | 56.2 | 56.68b | 55.9 | 56.96 | 56.1 | 56.65 | 55.8 | 49.80 | 57.49 |

| 6 | 20.4 | 20.6 | 20.4 | 20.7 | 20.49 | 23.0 | 20.2 | 20.10 | 19.3 | 22.00 | 19.2 | 20.70 | 19.2 | 19.51 | 22.28 |

| 7 | 40.3 | 40.3 | 42.0 | 40.4 | 42.31 | 42.8 | 41.1 | 42.02 | 32.5 | 41.52 | 40.3 | 39.24 | 39.2 | 40.84 | 41.71 |

| 8 | 45.3 | 45.3 | 44.7 | 45.1 | 45.17 | 45.0 | 45.4 | 45.20 | 43.4 | 44.51 | 42.5 | 48.81 | 48.8 | 47.63 | 44.17 |

| 9 | 56.8 | 56.0a | 56.7 | 56.0a | 56.70b | 56.3 | 55.9 | 55.20b | 50.8 | 55.40 | 55.0 | 47.57 | 48.3 | 47.89 | 55.55 |

| 10 | 39.3 | 38.0 | 39.4 | 39.2 | 39.15 | 40.1 | 39.3 | 39.44 | 39.2 | 39.64 | 39.4 | 39.72 | 39.4 | 40.00 | 40.09 |

| 11 | 18.0 | 18.5 | 18.3 | 18.3 | 17.93a | 19.0 | 19.3 | 18.13a | 18.2 | 19.06 | 18.5 | 18.75a | 18.6 | 77.52 | 18.43 |

| 12 | 26.9 | 31.2 | 26.3 | 31.3 | 26.06 | 26.8 | 29.2 | 26.90 | 27.0 | 27.06 | 29.7 | 25.31 | 25.6 | 33.97 | 33.53 |

| 13 | 49.0 | 44.7 | 45.5 | 41.4 | 48.64 | 45.9 | 42.7 | 48.93 | 36.0 | 45.64 | 47.9 | 40.92 | 41.1 | 44.41 | 44.28 |

| 14 | 37.7 | 40.8 | 37.3 | 38.1 | 37.36 | 37.8 | 38.6 | 37.81 | 36.0 | 37.88 | 37.5 | 43.71 | 40.4 | 39.79 | 40.13 |

| 15 | 58.0 | 45.0 | 53.4 | 44.7 | 57.66 | 53.9 | 48.9 | 57.80 | 65.7 | 55.54 | 55.2 | 135.39 | 135.7 | 47.41 | 49.39 |

| 16 | 79.4 | 55.9 | 81.9 | 45.9 | 79.16 | 81.7 | 66.4 | 79.29 | 69.5 | 89.16 | 222.5 | 145.82 | 145.6 | 155.24 | 156.32 |

| 17 | 24.5 | 182.5 | 66.4 | 14.8 | 24.05 | 66.5 | 50.4 | 24.47c | 59.9 | 70.05 | - | 60.63 | 61.1 | 104.09 | 103.69 |

| 18 | 33.5 | 33.5 | 33.5 | 33.2 | 26.89 | 29.3 | 33.6 | 24.26c | 33.6 | 28.93 | 33.6 | 28.87 | 35.5 | 30.08 | 29.38 |

| 19 | 21.6 | 21.5 | 21.5 | 21.6 | 64.98 | 180.1 | 21.6 | 205.80 | 21.6 | 182.64 | 21.7 | 180.90 | 21.5 | 184.05 | 184.00 |

| 20 | 18.0 | 17.3 | 17.8 | 17.4 | 18.11 | 16.0 | 17.8 | 16.40 | 17.5 | 15.74 | 18.0 | 15.25 | 17.6 | 15.93 | 16.02 |

| 1’ | 108.39 | ||||||||||||||

| 2’ | 26.81 | ||||||||||||||

| 3’ | 26.91 | ||||||||||||||

| Carbon | Compound / δC (in ppm) | ||||||||||||||

| 19 [56] | 20 [57](?) | 22 [34] | 22 [34] (P) | 22 [34](D) | 23 [60] | 27 [26] | 27 [34] | 29 [61] | 30 [38] | 30 [38] | 31 [39] | 32 [39] | 33 [38] | 33 [39] | |

| 1 | 41.3 | 40.5 | 39.79 | 40.9 | 40.3 | 38.7 | 18.3 | 17.4 | 17.3 | 17.5 | 18.2 | 17.7 | 17.6 | 17.3 | 18.3 |

| 2 | 18.7 | 18.3 | 20.07 | 19.7 | 19.0 | 27.6 | 26.8 | 27.6 | 27.5 | 27.1 | 26.8 | 24.1 | 24.0 | 27.5 | 26.9 |

| 3 | 42.0 | 35.7 | 40.84 | 38.5 | 37.9 | 80.6 | 120.5 | 120.6 | 120.4 | 120.0 | 120.4 | 123.2 | 123.1 | 120.5 | 120.4 |

| 4 | 33.3 | 39.3 | 43.60 | 43.7 | 42.5 | 42.7 | 144.5 | 144.4 | 144.4 | 143.7 | 144.4 | 139.9 | 139.9 | 144.5 | 144.4 |

| 5 | 56.1 | 56.9 | 49.80 | 49.5 | 46.3 | 55.8 | 38.2 | 38.3a | 38.3 | 38.0a | 38.4 | 38.5 | 38.2 | 38.3a | 38.2 |

| 6 | 20.3 | 20.5 | 35.00 | 30.4 | 29.3 | 20.1 | 36.9 | 36.5 | 35.9 | 36.4 | 36.8 | 37.8 | 37.7 | 36.4b | 36.8 |

| 7 | 40.4 | 41.7 | 77.52 | 76.2 | 75.0 | 41.3 | 27.6 | 27.0 | 26.8 | 26.4 | 27.5 | 28.8 | 28.7 | 26.9 | 27.5 |

| 8 | 44.2 | 44.0 | 47.63 | 48.9 | 48.0 | 43.9 | 36.2 | 36.3 | 36.1 | 36.0 | 36.1 | 37.3 | 37.2 | 36.4b | 36.3 |

| 9 | 56.1 | 56.2 | 47.89 | 47.4 | 48.6 | 55.8 | 40.0 | 38.7a | 38.1 | 38.3a | 39.9 | 39.9 | 39.9 | 38.4a | 38.3 |

| 10 | 39.3 | 38.7 | 40.00 | 39.5 | 38.8 | 39.6 | 46.4 | 46.6 | 46.4 | 46.1 | 46.3 | 44.5 | 44.5 | 46.6 | 46.5 |

| 11 | 18.1 | 18.2 | 19.51 | 18.5 | 17.7 | 18.3 | 35.5 | 35.1b | 35.5 | 35.0b | 35.4 | 35.1 | 35.0 | 35.0 | 36.3 |

| 12 | 33.3 | 33.2 | 33.97 | 34.0 | 33.3 | 33.0 | 29.5 | 35.6b | 35.4 | 35.8b | 29.4 | 29.4 | 29.3 | 36.9a | 35.0 |

| 13 | 44.2 | 44.2 | 44.41 | 44.3 | 43.4 | 43.9 | 30.9 | 31.0 | 30.6 | 30.6 | 31.0 | 30.9 | 31.1 | 164.4 | 164.6 |

| 14 | 39.9 | 39.7 | 39.10 | 39.1 | 38.4 | 38.5 | 41.6 | 41.7 | 36.5 | 41.0 | 41.5 | 41.6 | 41.5 | 114.9 | 114.8 |

| 15 | 49.2 | 49.1 | 47.41 | 46.6 | 45.6 | 48.8 | 179.4 | 179.8 | 62.8 | 172.8 | 173.8 | 179.4 | 173.8 | 172.0 | 172.1 |

| 16 | 156.0 | 155.9 | 155.24 | 156.2 | 155.4 | 155.4 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 19.6 | 19.5 | 19.9 | 19.8 | 19.8 | 19.5 | 19.5 |

| 17 | 102.8 | 103.0 | 104.09 | 103.6 | 103.2 | 103.1 | 16.0 | 16.1 | 15.7 | 15.5 | 15.9 | 16.0 | 15.9 | 15.9 | 16.0 |

| 18 | 33.7 | 27.1 | 30.08 | 28.6 | 28.5 | 22.8 | 19.9 | 18.4 | 18.3 | 18.0 | 19.9 | 33.0 | 33.0 | 18.3 | 20.0 |

| 19 | 21.7 | 65.6 | 184.05 | 178.2 | 179.0 | 64.3 | 18.0 | 20.0 | 19.3 | 19.5 | 18.0 | 20.1 | 19.9 | 20.0 | 18.0 |

| 20 | 17.6 | 18.1 | 15.93 | 15.7 | 15.4 | 18.3 | 18.5 | 18.1 | 17.8 | 17.8 | 18.4 | 17.4 | 17.3 | 17.9 | 18.3 |

| C=O | 178.6 | ||||||||||||||

| MeCO | 20.8 | ||||||||||||||

| OMe | 50.6 | 51.3 | 51.3 | ||||||||||||

| Carbon | Compound / δC (in ppm) | ||||||||||||||

| 34 [62] | 35 [63] | 36 [38] | 37 [38] | 38 [40] | 39 [41] | 40 [41] | 41 [41] | 42 [41] | 43 [41] | 44 [38] | 45 [40] | 46 [40] | 47 [38] | 48 [41] | |

| 1 | 18.37 | 18.40 | 17.5 | 18.6 | 18.1 | 29.4 | 16.2 | 18.2 | 27.3a | 28.9 | 35.1a | 35.6 | 35.6 | 35.6a | 34.3a |

| 2 | 26.98 | 26.92 | 27.1 | 24.1 | 27.7 | 125.6 | 30.3 | 27.4 | 65.6 | 69.5 | 199.1 | 201.2 | 200.2 | 200.0 | 200.5 |

| 3 | 120.52 | 120.46 | 120.0 | 123.3 | 120.3 | 171.0 | 76.2 | 120.4 | 122.1 | 124.4 | 128.5 | 125.5 | 125.5 | 125.5 | 127.4 |

| 4 | 144.60 | 144.50 | 143.7 | 139.8 | 144.4 | 168.7 | 76.5 | 144.5 | 150.1 | 147.9 | 168.6 | 173.4 | 171.0 | 172.6 | 172.6 |

| 5 | 38.28 | 38.30 | 38.0a | 37.9 | 38.3 | 50.6 | 38.3 | 38.1 | 38.0 | 38.0 | 38.6c | 40.0 | 38.8 | 39.9b | 39.7 |

| 6 | 36.94 | 36.99 | 36.4 | 37.6a | 36.1 | 34.4 | 32.4 | 36.8 | 36.4 | 36.5 | 36.8b | 36.0 | 35.5 | 34.8a | 35.5 |

| 7 | 27.61 | 27.63 | 26.4 | 28.9 | 26.8 | 28.3 | 26.4 | 26.8 | 27.2a | 27.2 | 29.0 | 27.0 | 26.9 | 26.9 | 26.8 |

| 8 | 36.36 | 36.41 | 36.0 | 37.5 | 36.8 | 37.1 | 36.0 | 36.1 | 36.3 | 35.9 | 37.3 | 36.1 | 36.1 | 36.1 | 35.8 |

| 9 | 38.72 | 38.72 | 38.3a | 38.9 | 38.1 | 37.5 | 41.2 | 38.3 | 38.9 | 38.6 | 39.3c | 38.6 | 38.6 | 38.8b | 38.3 |

| 10 | 46.53 | 46.60 | 46.0 | 44.9 | 46.3 | 53.9 | 40.7 | 46.3 | 40.4 | 45.2 | 45.7 | 45.7 | 45.7 | 45.6 | 45.5 |

| 11 | 36.63 | 36.72 | 34.2 | 35.0 | 31.8 | 33.5 | 32.2 | 31.8 | 31.0 | 31.8 | 35.4a | 34.9 | 34.9 | 34.9a | 31.1 |

| 12 | 32.95 | 32.97 | 37.7 | 37.0a | 35.2 | 35.5 | 35.4 | 35.3 | 36.4 | 35.2 | 36.2b | 36.0 | 34.7 | 35.9a | 34.7a |

| 13 | 140.93 | 143.22 | 160.8 | 164.5 | 73.3 | 73.0 | 73.5 | 73.4 | 73.2 | 73.3 | 30.7 | 30.8 | 30.4 | 30.9 | 73.0 |

| 14 | 123.13 | 118.03 | 114.5 | 115.1 | 145.2 | 144.9 | 145.0 | 145.1 | 146.4 | 145.0 | 41.4 | 41.5 | 36.9 | 41.3 | 144.8 |

| 15 | 59.51 | 61.44 | 166.5 | 172.4 | 111.6 | 111.9 | 111.6 | 111.8 | 110.9 | 111.9 | 178.7 | 178.9 | 63.0 | 173.4 | 111.9 |

| 16 | 16.52 | 16.70 | 18.5 | 19.6 | 27.4 | 27.8 | 27.4 | 27.7 | 26.3 | 27.7 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 19.9 | 19.8 | 27.7 |

| 17 | 16.07 | 15.98 | 15.5 | 16.1 | 15.8 | 15.0 | 15.9 | 15.9 | 15.8 | 15.9 | 16.0 | 15.7 | 15.8 | 15.7 | 15.6 |

| 18 | 18.45 | 17.92 | 18.0 | 20.0 | 18.3 | 11.7 | 21.3 | 18.0 | 17.9 | 17.7 | 20.5 | 18.4 | 18.5 | 18.4 | 18.9b |

| 19 | 20.03 | 19.99 | 19.5 | 33.2 | 19.8 | 16.9 | 17.2 | 19.8 | 18.3 | 19.9 | 32.1 | 18.9 | 18.7 | 18.9 | 18.2b |

| 20 | 18.07 | 18.34 | 17.8 | 17.9 | 17.8 | 18.2 | 18.5 | 18.4 | 18.3 | 18.5 | 18.0 | 17.9 | 18.0 | 18.0 | 17.9 |

| C=O | 170.94 | 178.9 | |||||||||||||

| MeCO | 20.94 | 20.8 | |||||||||||||

| OMe | 50.1 | 51.4 | |||||||||||||

| Compound / δC (in ppm) | |||||||||||||||

| Carbon | 49 [38] | 50 [38] | 51 [38] | 54 [41] | 56 [46] | 57 [40] | 58 [64] | 60 [40] | 61 [54]A | 62 [55] | 63 [65] | 65 (?) [66] | 66 [40] | 67 [40] | |

| 1 | 35.4a | 35.4a | 35.6a | 22.0 | 74.18 | 39.1 | 39.8 | 39.0 | 40.4 | 33.1 | 39.1 | 19.45 | 43.9 | 36.9 | |

| 2 | 200.3 | 200.0 | 200.2 | 79.2 | 128.68 | 18.2 | - | 18.2 | 19.0 | 21.7 | 19.4 | 22.36 | 19.5 | 19.0 | |

| 3 | 128.5 | 125.3 | 125.4 | 116.7 | 136.84 | 42.1 | 41.9 | 41.9 | 42.7 | 35.4 | 42.1 | 24.51 | 42.0 | 41.2 | |

| 4 | 167.5 | 172.3 | 172.7 | 155.0 | 80.48 | 33.1 | - | 33.3 | 33.7 | 39.1 | 33.6 | 33.64 | 34.5 | 33.2 | |

| 5 | 38.6b | 39.8b | 39.9b | 37.8 | 37.16 | 55.9 | 56.1 | 55.8 | 56.9 | 36.6 | 55.5 | 55.59 | 57.5 | 51.8 | |

| 6 | 36.7a | 34.8a | 34.9a | 33.2 | 25.59 | 18.1 | 23.5 | 18.1 | 21.1 | 28.6 | 24.5 | 32.75 | 69.4 | 19.0 | |

| 7 | 28.9 | 26.7 | 26.9 | 27.1 | 17.33 | 41.3 | 44.7 | 40.5 | 45.1 | 37.4 | 38.3 | 38.41 | 47.7 | 33.5 | |

| 8 | 36.6 | 36.1 | 36.1 | 36.4 | 47.58 | 73.3 | 74.4 | 73.3 | 73.9 | 160.6 | 148.3 | 148.17 | 144.0 | 125.4 | |

| 9 | 39.9b | 38.7 | 38.7b | 39.1 | 35.28 | 59.3 | 61.3 | 58.2 | 62.3 | 48.6 | 56.2 | 57.20 | 56.7 | 140.4 | |

| 10 | 45.7 | 45.6 | 45.8 | 40.4 | 44.49 | 38.9 | 39.2 | 38.8 | 39.8 | 40.0 | 39.7 | 39.80 | 40.9 | 37.2 | |

| 11 | 34.0 | 34.2a | 34.0a | 30.7 | 41.90 | 22.3 | 20.5 | 22.4 | 20.0 | 27.5 | 21.5 | 38.96 | 21.6 | 25.3 | |

| 12 | 36.8a | 35.9a | 35.9a | 36.1 | 70.66 | 42.1 | 44.5 | 41.9 | 46.2 | 29.8 | 40.1 | 42.21 | 39.5 | 41.7 | |

| 13 | 160.3 | 162.6 | 160.3 | 73.9 | 124.79 | 30.9 | 163.9 | 30.9 | 73.3 | 30.8 | 164.3 | 160.69 | 160.7 | 31.1 | |

| 14 | 115.2 | 115.1 | 115.3 | 146.3 | 108.40 | 40.5 | 114.7 | 144.7 | 147.5 | 41.4 | 114.6 | 115.73 | 115.2 | 145.9 | |

| 15 | 167.0 | 171.2 | 167.1 | 111.2 | 139.66 | 177.9 | 171.5 | 111.8 | 110.7 | 179.8 | 171.8 | 166.40 | 167.3 | 112.0 | |

| 16 | 19.1 | 19.3 | 19.1 | 25.0 | 143.96 | 19.5 | 19.4 | 19.5 | 27.8 | 19.8 | 19.2 | 14.51 | 19.0 | 20.0 | |

| 17 | 15.9 | 15.5 | 15.7 | 15.6 | 175.48 | 30.5 | 24.0 | 30.4 | 24.5 | 102.5 | 106.4 | 21.73 | 110.3 | 19.4 | |

| 18 | 20.5 | 18.2 | 18.4 | 18.3 | 172.37 | 21.5 | 21.5 | 21.5 | 33.7 | 18.2 | 33.6 | 25.26 | 23.6 | 21.5 | |

| 19 | 32.1 | 18.7 | 18.9 | 18.1 | 27.00 | 33.3 | 33.4 | 33.1 | 21.8 | 20.8 | 21.7 | 33.64 | 33.7 | 33.2 | |

| 20 | 17.8 | 17.6 | 17.9 | 18.4 | 24.31 | - | 15.4 | - | 15.8 | 15.9 | 14.5 | 106.53 | 17.1 | 19.3 | |

| 1’ | 50.8 | ||||||||||||||

| 2’ | |||||||||||||||

| 3’ | 50.7 | 50.56 | 50.8 | ||||||||||||

| Carbon | Compound / δC (in ppm) | Carbon | Compound / δC (in ppm) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 [ 31] | 25 [ 31] | 26 [ 31] | 24 | 25 | 26 | ||

| 1 | 40.3 | 40.4 | 40.4 | 1’ | - | - | - |

| 2 | 18.6 | - | - | 2’ | 112.7 | 112.8 | 112.5 |

| 3 | 41.9 | 42.0 | 42.0 | 3’ | 143.1 | - | - |

| 4 | 33.3 | - | - | 4’ | 147.5 | 146.8 | 146.2 |

| 5 | 56.0 | 56.1 | 56.2 | 4a’ | - | - | - |

| 6 | 20.5 | - | 20.5 | 4b’ | 131.0 | - | 131.0 |

| 7 | 42.1 | 42.0 | 42.0 | 5’ | 119.2 | 127.4 | 119.2 |

| 8 | 44.9 | - | - | 6’ | 131.0 | 130.5 | - |

| 9 | 56.7 | 56.6 | 56.5 | 7’ | 108.0 | - | 108.0 |

| 10 | 39.4 | - | - | 8’ | 156.9 | 130.2 | 156.9 |

| 11 | 18.3 | - | - | 8a’ | 120.2 | 128.5 | 120.2 |

| 12 | 26.3 | 27.1 | 27.4 | 9’ | 121.2 | 126.5 | 121.1 |

| 13 | 46.3 | 46.5 | 43.5 | 10’ | 145.9 | - | - |

| 14 | 37.2 | 37.5 | 38.1 | 10a’ | - | 118.3 | 119.2 |

| 15 | 53.3 | 53.4 | 51.0 | 11’ | 167.2 | 167.5 | 167.2 |

| 16 | 80.1 | 80.0 | - | OCH2O | 102.4 | 103.0 | 102.4 |

| 17 | 69.6 | 70.2 | 63.7 | OMe | 56.2 | 56.2 | |

| 18 | 33.6 | 33.6 | 33.6 | ||||

| 19 | 21.5 | 22.0 | 21.6 | ||||

| 20 | 17.8 | 18.0 | 17.8 | ||||

Acknowledgements

References

- Neinhuis, C; Wanke, S.; Hilu, K.W.; Müller, K.; Borsch, T. Phylogeny of Aristolochiaceae based on parsimony, likelihood and Bayesian analyses of trnL-trnF sequences. Plant Syst. Evol. 2005, 250, 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Wanke, S.; Gonzales, F.; Neinhuis, C. Systematics of Pipevines: Combining morphological and fast-evolving molecular characters to investigate the relationships within subfamily Aristolochioideae (Aristolochiaceae). Inter. J. Plant Sci. 2006, 167, 1215–1227. [Google Scholar]

- Wanke, S.; Jaramillo, M.A.; Borsch, T.; Samain, M.-S.; Quandt, D.; Neinhuis, C. Evolution of Piperales – matK gene and trnK intron sequence data reveal lineage specific resolution contrast. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2007, 42, 477–497. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.S.; Tsai, Y.L.; Damu, A.G.; Kuo, P.C.; Wu, P.L. Constituents from the root and stem of Aristolochia elegans. J. Nat. Prod. 2002, 65, 1522–1525. [Google Scholar]

- Che, C.-T.; Almed, M.S.; Kang, S.S.; Waller, D.P.; Bengel, A.S.; Martin, A.; Rajamahendran, P.; Bunyapraphatsara, J.; Lankin, D.C.; Cordell, G.A.; Soejarto, D.D.; Wijesekera, R.O.B.; Fong, H.H.S. Studies on Aristolochia III. Isolation and biological evaluation of constituents of Aristolochia indica roots for fertility-regulationg activity. J. Nat. Prod. 1984, 47, 331–341. [Google Scholar]

- Corrêa, M.P. Dicionário das Plantas Úteis do Brasil e das Exóticas Cultivadas; Imprensa Nacional: Rio de Janeiro, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, L.M.X.; Bolzani, V.S.; Trevisan, L.M.V.; Luiz, V. ent-Cauranos e lignanas de Aristolochia elegans. Quím. Nova 1990, 13, 250–251. [Google Scholar]

- Lajide, L.; Escoubas, P.; Mizutani, J. Antifeedant activity of metabolites of Aristolochia albida against the Tobacco cutworm Spodoptera litura. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1993, 41, 669–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemos, V.S.; Thomas, G.; Barbosa Filho, J.M. Pharmacological studies on Aristolochia papillaris Mast (Aristolochiaceae). J. Ethnopharmacol. 1993, 40, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terada, S.; Motomiya, T.; Yoshioka, K.; Narita, T.; Yasui, S.; Takase, M. Antiallergic substance from Assarum sagittarioides and synthesis of some analogs. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1987, 35, 2437–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.Q.; Liao, Z.X.; Cai, X.Q.; Lei, J.C.; Zouc, G.L. Composition, antimicrobial activity and citotoxicity of essential oils from Aristolochia mollissima. Environm. Toxic. Pharm. 2007, 23, 162–167. [Google Scholar]

- Kubmarawa, D.; Ajoku, G.A.; Enwerem, N.M.; Okorie, D.A. Preliminary phytochemical and antimicrobial screening of 50 medicinal plants from Nigeria. Afric. J. Biotech. 2007, 6, 1690–1696. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, L.M.X.; Bolzani, V.S.; Trevisan, L.M.V.; Grigolli, T.M. Terpenes from Aristolochia triangularis. Phytochemistry 1990, 29, 660–662. [Google Scholar]

- Shafi, P.M.; Rosamma, M.K.; Jamil, K.; Reddy, P.S. Antibacterial activity of the essential oil from Aristolochia indica. Fitoterapia 2002, 73, 439–441. [Google Scholar]

- Nok, A.J. A novel nonhemorrhagic protease from the Africa puff adder (Bitis arietans) venom. J. Biochem. Molec. Toxic. 2001, 15, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.-S.; Damu, A.G.; Su, C.-R.; Kuo, P.-C. Terpenoids of Aristolochia and their biological activities. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2004, 21, 594–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinl, W.; Pabel, U.; Osterloh-Quiroz, M.; Hengstler, J.G.; Glatt, H. Human sulphotransferases are involved in the activation of aristolochic acids and are expressed in renal target tissue. Intern. J. Cancer 2006, 118, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, M.-C. M.; Nortier, J.; Vereerstraeten, P.; Vanherweghem, J.-L. Progression rate of Chinese herb nephropathy: impact of Aristolochia fangchi ingested dose. Nephrol Dial. Transplant. 2002, 17, 408–412. [Google Scholar]

- Mix, D.B.; Guinaudeau, H.; Shamma, M. The aristolochic acid and aristolactams. J. Nat Prod. 1982, 45, 657–666. [Google Scholar]

- Stiborova, M.; Frei, E.; Breuer, A.; Bieler, C.A.; Schmeiser, H.H. Aristolactam I a metabolite of aristolochic acid I upon activation forms and adduct found in DNA of patients with chinese herts nephropathy. Experim. Toxic. Pathol. 1999, 51, 421–427. [Google Scholar]

- Grollman, A.P.; Shibutani, S.; Moriya, M.; Miller, F.; Wu, L.; Moll, U.; Suzuki, N.; Fernandes, A.; Rosenquist, T.; Medverec, Z.; Jakovina, K.; Brdar, B.; Slade, N.; Turesky, R.J.; Goodenough, A.K.; Rieger, R.; Vukelić, M.; Jelaković, B. Aristolochic acid and the etiology of endemic (Balkan) nephropathy. PNAS 2007, 104, 12129–12134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rastrelli, L.; Capasso, A.; Pizza, C.; De Tommasi, N.; Sorrentino, L. New protopine and benzyltetrahydroprotoberberine alkaloids from Aristolochia constricta and their activity on isolated Guinea-Pig ileum. J. Nat. Prod. 1997, 60, 1065–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.S.; Chan, Y.Y.; Leu, Y.L. The constituents of the root and stem of Aristolochia cucurbitifolia hayata and their biological activity. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2000, 48, 1006–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.S.; Chan, Y.Y.; Wu, P.L.; Li, C.Y.; Mori, Y. Four aristolochic acid esters of rearranged ent-elemane sesquiterpenes from Aristolochia heterophylla. J. Nat. Prod. 1999, 62, 348–351. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T.S.; Tsai, Y.L.; Wu, P.L.; Leu, Y.L.; Lin, F.W.; Lin, J.K. Constituents from the leaves of Aristolochia elegans. J. Nat. Prod. 2000, 63, 692–693. [Google Scholar]

- Leitão, G.G.; Kaplan, M.A.C. Chemistry of the genus Aristolochia. Rev. Bras. Farm. 1992, 73, 65–75. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.-S.; Kuo, P.-C.; Tsai, Y.-L.; Damu, A.G.; Wu, T.-S. The alkaloids and other constituents from the root and stem of Aristolochia elegans. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004, 12, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, M.S.; Guilhon, G.M.S.P.; Conserva, L.M. Kauranoids from Aristolochia rodriguesii. Fitoterapia 1998, 69, 277–278. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, G.E.; Adams, L.S.; Rosales, J.C.; Jacobs, H.; Heber, D.; Seeram, N.P. Kaurene diterpenes from Laetia thamnia inhibit the growth of human cancer cells in vitro. Cancer Lett. 2006, 244, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, A.A.M.; El-Sebakhy, N.A. ent-Kaurane-16α,17-diol and (–)-cubebin as natural products from Aristolochia elegans. Pharmazie 1981, 36, 291–294. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, L.M.X.; Nascimento, I.R. Diterpene esters of aristolochic acids from Aristolochia pubescens. Phytochemistry 2003, 63, 953–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucker, G.; Langmann, B.; Siqueira, N.S. Constituents of Aristolochia triangularis. Planta Med. 1981, 41, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaitan, R.; Gómez, H.A.; Tapia, S.; Villadiego, A.M.; Méndez, D. (–)-Acido-II-hidroxikaur-16-en-19-óico, um nuevo kaureno aislado de Aristolochia anguicida Jacq. Rev. Latinoamer. Quim. 2002, 30, 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- Fraga, B.M. On the structure of an ent-kaurene diterpene from Aristolochia anguicida. Rev. Latinoamer. Quim. 2004, 32, 76–79. [Google Scholar]

- Lajide, L.; Escoubas, P.; Mizutani, J. Termite antifeedant activity in Detarium microcarpum. Phytochemistry 1995, 40, 1101–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, M.A.; Bedir, E.; Toyang, N.J.; Khan, I.A.; Harries, M.D.; Wedge, D.E. Antifungal clerodane diterpenes from Macaranga monandra (L.) Muell et Arg. (Euphorbiaceae). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 7607–7610. [Google Scholar]

- Messiano, G.B.; Vieira, L.; Machado, M.B.; Lopes, L.M.X.; Bortoli, S.A.; Zukerman-Schpector, J. Evaluation of insecticidal activity of diterpenes and lignans from Aristolochia malmeana against Anticarsia gemmatalis. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 2655–2659. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, L.M.X.; Bolzani, V.S.; Trevisan, L.M.V. Clerodane diterpenes from Aristolochia species. Phytochemistry 1987, 26, 2781–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitão, G.G.; Kaplan, M.A.C.; Galeffi, C. epi-Populifolic acid from Aristolochia cymbifera. Phytochemistry 1992, 31, 3277–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, L.M.X.; Bolzani, V.S. Lignans and diterpenes of three Aristolochia species. Phytochemistry 1988, 27, 2265–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomm, M.D.; Zukerman-Schpector, J.; Lopes, L.M.X. Rearranged (4→2) –abeo-clerodane and clerodane diterpenes from Aristolochia chamissonis. Phytochemistry 1999, 50, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, I.D.; Ferreira-Alves, D.L.; Piló-Veloso, D.; Nakamura-Craig, M. Evidence of the involvement of biologic amines in the antinoceptive effect of a vouacapan extracted from Pterodon polygalaeflorus Benth. J. Ethnopharm. 1996, 55, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, S.G.; Rodrigues, B.L.; Fernandes, N.G.; Stefani, G.M.; Piló-Veloso, D. Structure of 6α,7β-dihydroxyvouacapan-17β-oic acid. Acta Crystallogr. 1997, C53, 982–984. [Google Scholar]

- Belinelo, V.J.; Reis, G.T.; Stefani, G.M.; Ferreira-Alves, D.L.; Piló-Veloso, D. Synthesis of 6α,7β-dihydroxyvouacapan-17β-oic acid derivatives. Part IV: Mannich base derivatives and its activities on the electrically stimulated guinea-pig ileum preparation. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2002, 13, 830–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King-Díaz, B.; Pérez-Reyes, A.; Santos, F.J.L.; Ferreira-Alves, D.L.; Piló-Veloso, D.; Carvajal, S. U.; Lotina-Hennsen, B. Natural diterpene derivative β-lactone as photosystem II inhibitor on spinach chloroplast. Pest. Biochem. Physiol. 2006, 84, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, M.K.; Haruna, A.K.; Johnson, E.C.; Houghton, P.J. Structural elucidation of columbin, a diterpene isolated from the rhizomes of Aristolochia albida. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 1997, 59, 34–37. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, F.J.L.; Alcântara, A.F.C.; Ferreira-Alves, D.L.; Piló-Veloso, D. Theoretical and experimental NMR studies of the Swern oxidation of methyl 6α,7β-dihydroxyvouacapan-17β-oate. Struct. Chem. 2008, 19, 624–631. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, J.A.; Vincent, G.G.; Burden, R.S. Diterpenes from Nicotiana glutinosa and their effect on fungal growth. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1974, 85, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, H.G.; Reid, W.W.; Deletang, J. Plant growth inhibiting properties of diterpenes from tobacco. Plant Cell Physiol. 1977, 18, 711–714. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, J.A.; Carter, G.A.; Burden, R.S.; Wain, R.L. Control of rust diseases by diterpenes from Nicotiana glutinosa. Nature 1975, 255, 328–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulubelen, A.; Miski, M.; Johansson, C.; Lee, E.; Mabry, T.J.; Matlin, S.A. Terpenoids from Salvia palaestina. Phytochemistry 1985, 24, 1386–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decorzant, R.; Vial, C.; Naef, F.; Whitesides, G.M. A short synthesis of ambrox from sclareol. Tetrahedron 1987, 43, 1871–1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baratta, M.T.; Ruberto, G.; Tringali, C. Constituents of the pods of Piliostigma thonningii. Fitoterapia 1999, 70, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouzi, S.A.; McChesney, J.D. Microbial models of mammalian metabolism: fungal metabolism of the diterpene sclareol by Cunninghamella species. J. Nat. Prod. 1991, 54, 483–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrahondo, J.E.; Acevedo, C. Terpenoides de Aristolochia ringens. An. Asoc. Quim. Argent. 1990, 78, 355–358. [Google Scholar]

- Hanson, J.R.; Siverns, M.; Piozzi, F.; Savona, G. The 13C Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectra of kauranoid diterpenes. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. I 1976, 114–117. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.-C.; Hung, Y.-C.; Chang, F.-R.; Cosentino, M.; Wang, H.-K.; Lee, K.-H. Identification of ent-16β,17-dihydroxykauran-19-oic acid as an anti-HIV principle and isolation of the new diterpenoids Annosquamosins A and B from Annona squamosa. J. Nat. Prod. 1996, 59, 635–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etse, J.T.; Gray, A.I.; Waterman, P.G. Chemistry in the Annonaceae - XXIV. Kaurane and kaur-16-ene diterpenes from the stem bark of Annona riticulata. J. Nat. Prod. 1987, 50, 979–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljančić, I.; Macura, S.; Juranić, N.; Andjelković, S.; Randjelović, N.; Milosavljević, S. Diterpenes from Achillea clypeolata. Phytochemistry 1996, 43, 169–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piozzi, F.; Savona, G.; Hanson, J.R. Kaurenoid diterpenes from Satchys lanata. Phytochemistry 1980, 19, 1237–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, R.; Pandey, R.C.; Dev, S. Higher isoprenoids - IX. Diterpenoids from the oleoresin of Hardwickia pinnata Part 2: Kolavic, kolavenic, kolavenolic and kolavonic acids. Tetrahedron 1979, 35, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, H.; Tiliacos, N.; Faure, R. Copaiba oil: isolation and characterization of a new diterpenoid with the dinorlabdane skeleton. Phytochemistry 1999, 51, 1013–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urones, J.G.; Marcos, I.S.; Cubillo, L.; Monje, V.A.; Hernández, J.M.; Basade, P. Derivatives of malonic acid in Parentucellia latifolia. Phytochemistry 1989, 28, 651–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, R.; Mangoni, L. Diterpenes from Araucaria bidwilli. Phytochemistry 1974, 13, 467–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavin, A.-L.; Hay, A.-E.; Marston, A.; Stoeckli-Evans, H.; Scopelliti, R.; Diallo, D.; Hostettmann, K. Bioactive diterpenes from the fruits of Detarium microcarpum. J. Nat. Prod. 2006, 69, 768–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.K.; Wolf, H.R. Synthesis of ethers of the enantio-14,15-dinorlabdane series from eperuic acid. Helv. Chim. Acta 1978, 61, 1004–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds 27 and 45 are available from the authors.

© 2009 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Pacheco, A.G.; Machado de Oliveira, P.; Piló-Veloso, D.; Flávio de Carvalho Alcântara, A. 13C-NMR Data of Diterpenes Isolated from Aristolochia Species. Molecules 2009, 14, 1245-1262. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules14031245

Pacheco AG, Machado de Oliveira P, Piló-Veloso D, Flávio de Carvalho Alcântara A. 13C-NMR Data of Diterpenes Isolated from Aristolochia Species. Molecules. 2009; 14(3):1245-1262. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules14031245

Chicago/Turabian StylePacheco, Alison Geraldo, Patrícia Machado de Oliveira, Dorila Piló-Veloso, and Antônio Flávio de Carvalho Alcântara. 2009. "13C-NMR Data of Diterpenes Isolated from Aristolochia Species" Molecules 14, no. 3: 1245-1262. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules14031245