Organocatalyzed Asymmetric α-Oxidation, α-Aminoxylation and α-Amination of Carbonyl Compounds

Abstract

:Outline

- Introduction

- α-Amination reactions

- 2.1. α-Amination with azodicarboxylate esters

- 2.1.1 Simple aldehydes and ketones

- 2.1.2 Other carbonyl substrates

- 2.1.3. Applications

- 2.2. α-Sulfamidation

- 2.3. α-Hydroxyamination

- α-Aminoxylation reactions

- 3.1. α-Aminoxylation with nitrosobenzene

- 3.1.1. Substrates

- 3.1.2. Catalysts

- 3.1.3. Applications

- 3.1.4. Aminoxylation vs. nitrosoaldol reactions

- 3.2. α-Aminoxylation with TEMPO

- α-Oxidation reactions

- 4.1. α-Oxybenzoylation

- 4.2. α-Oxidation with molecular oxygen

- 4.3. α-Oxidation with hydroperoxides

- 4.4. α-Aryloxylation with o-quinones

- 4.5. α-Oxidation with oxaziridine and iodosobenzene

- 4.6. α-Oxysulfonation catalyzed by iodoarenes

- Conclusions and Outlook

1. Introduction

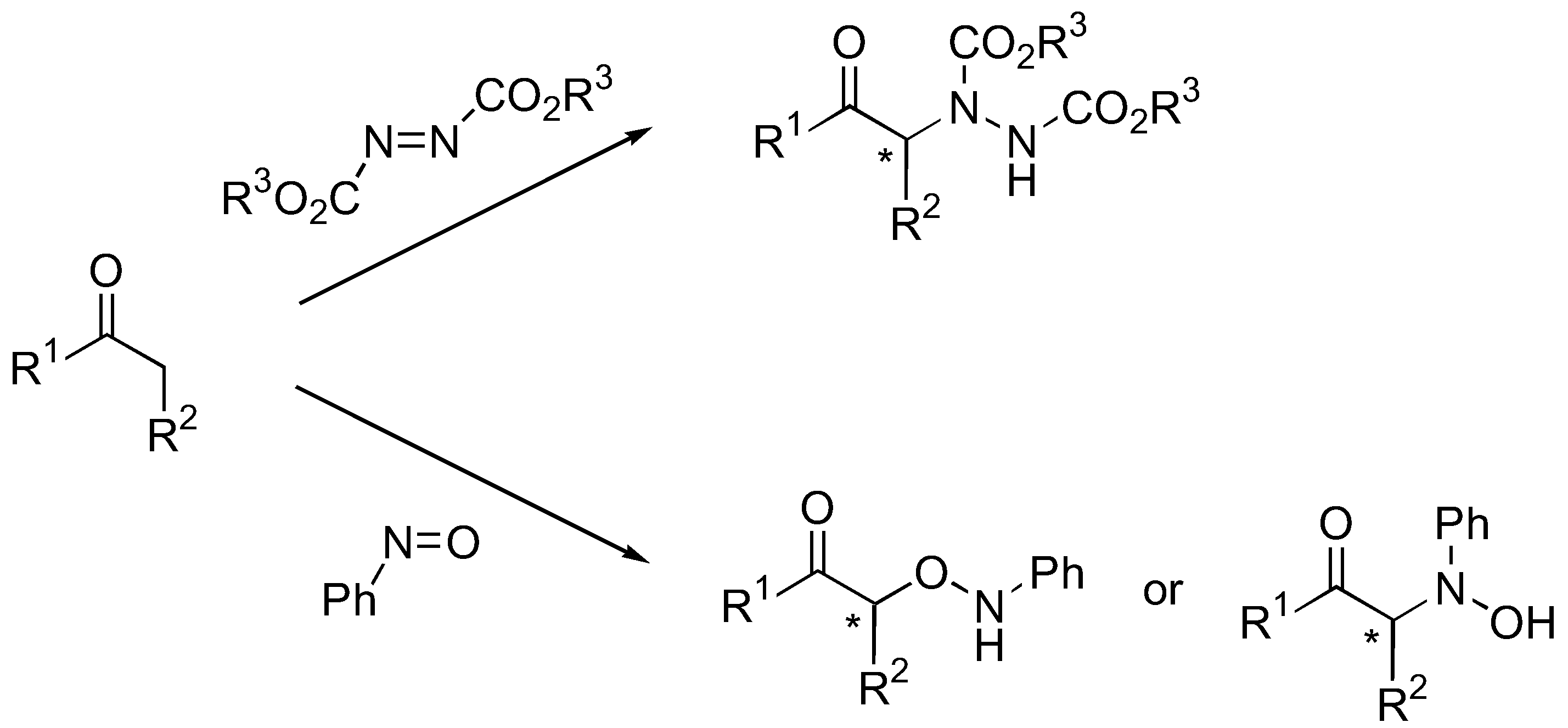

2. α-Amination Reactions

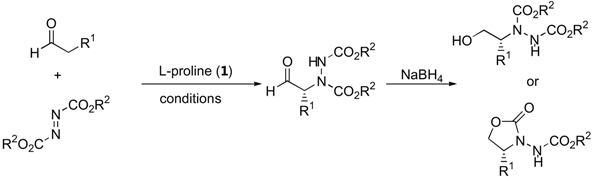

2.1. α-Amination with Azodicarboxylate Esters

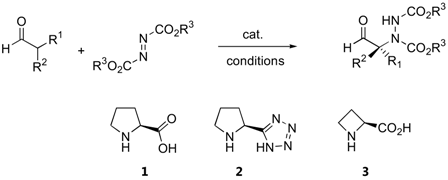

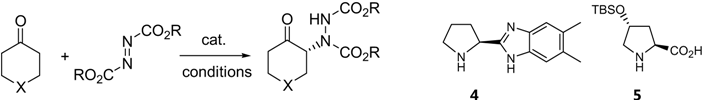

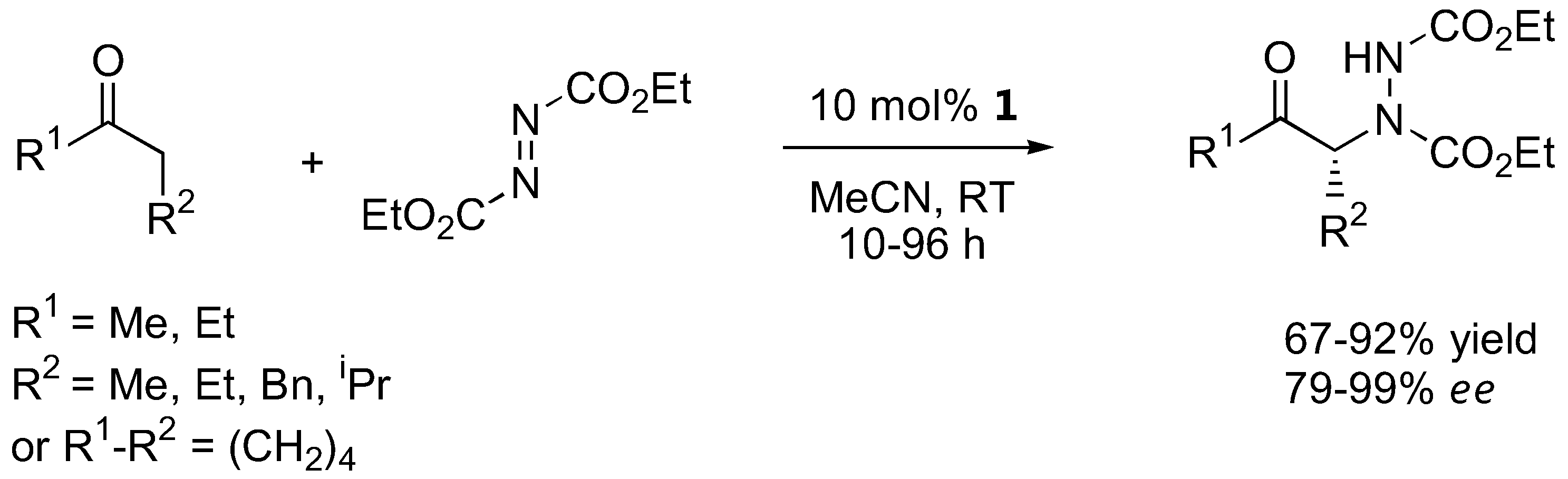

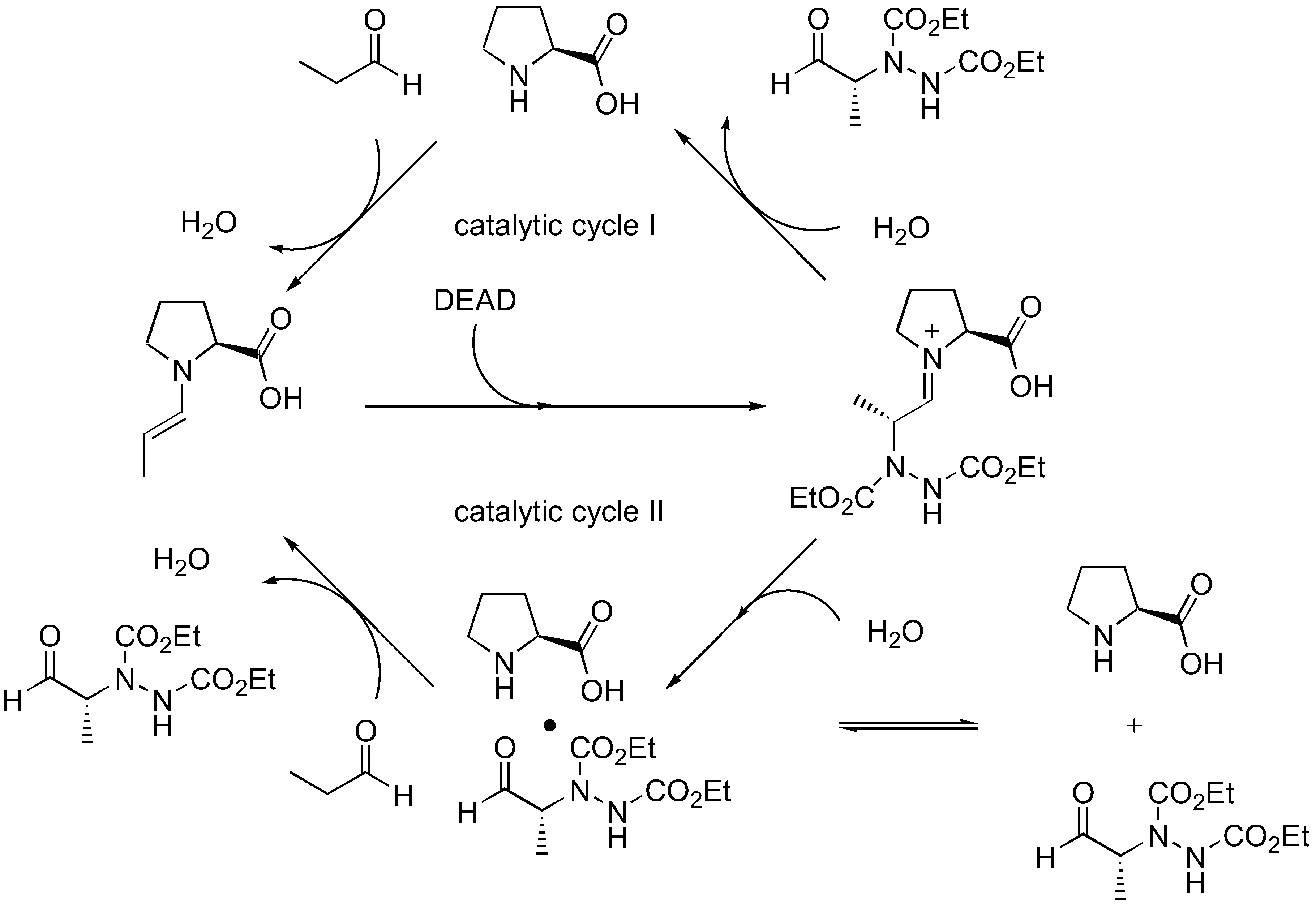

2.1.1. Simple aldehydes and ketones

| R1 | R2 | Conditions | Yield (%) | ee (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Me, Et, iPr, tBu, allyl, Bn | Et, Bn | 10 mol% 1, CH2Cl2, RT | 57–92 | 89–95 | [12] |

| Me, iPr, nPr, nBu, Bn | Bn | 10 mol% 1, CH3CN, 0 °C to RT, 3h | 93–99 | >95 | [13] |

| R1 | R2 | R3 | Conditions | Yield (%) | ee (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Et, n Bu, Ph, 2-Naph, | Me, | Et, | 50 mol% 1, | 17–87 | 4–28 (R1 = alkyl) | [21] |

| subst. Ph | Et | Bn | CH2Cl2, RT, | 76–85 (R1 = aryl) | ||

| 2.5–9 d | ||||||

| Et, Ph, 2-Naph, | Me, | Et, | 50 mol% 3, | N/A | 6 (R1 = alkyl) | [21] |

| subst. Ph | Et | Bn | CH2Cl2, RT, | 49–78 (R1 = aryl) | ||

| 2.5–9 d | ||||||

| Me, Et, Pr, Bu, Ph, | Me, | Et, | 50 mol% 1, | 19–99 | 0–39 (R1 = alkyl) | [22] |

| 2-Naph, subst. Ph, | Et | Bn | CH2Cl2, RT | 35–86 (R1 = aryl) | ||

| 2-thienyl | ||||||

| H, 2-Naph, | Me | Et | 50 mol% 1 or 2, | 54–97 | 52–91 | [24] |

| 4-subst. Ph | MeCN, microwave | (6–85)a | (24–84)a | |||

| 4-BrC6H4CH2 | Me | Bn, | 15 mol% 2, MeCN, | 95 | 80 | [23] |

| Et | RT, 3h | (90)b | (44)b | |||

| Bn | 20–30 mol% 1 or ent-1, MeCN, RT,1–4 h | 75–99 | >99 | [25] | |

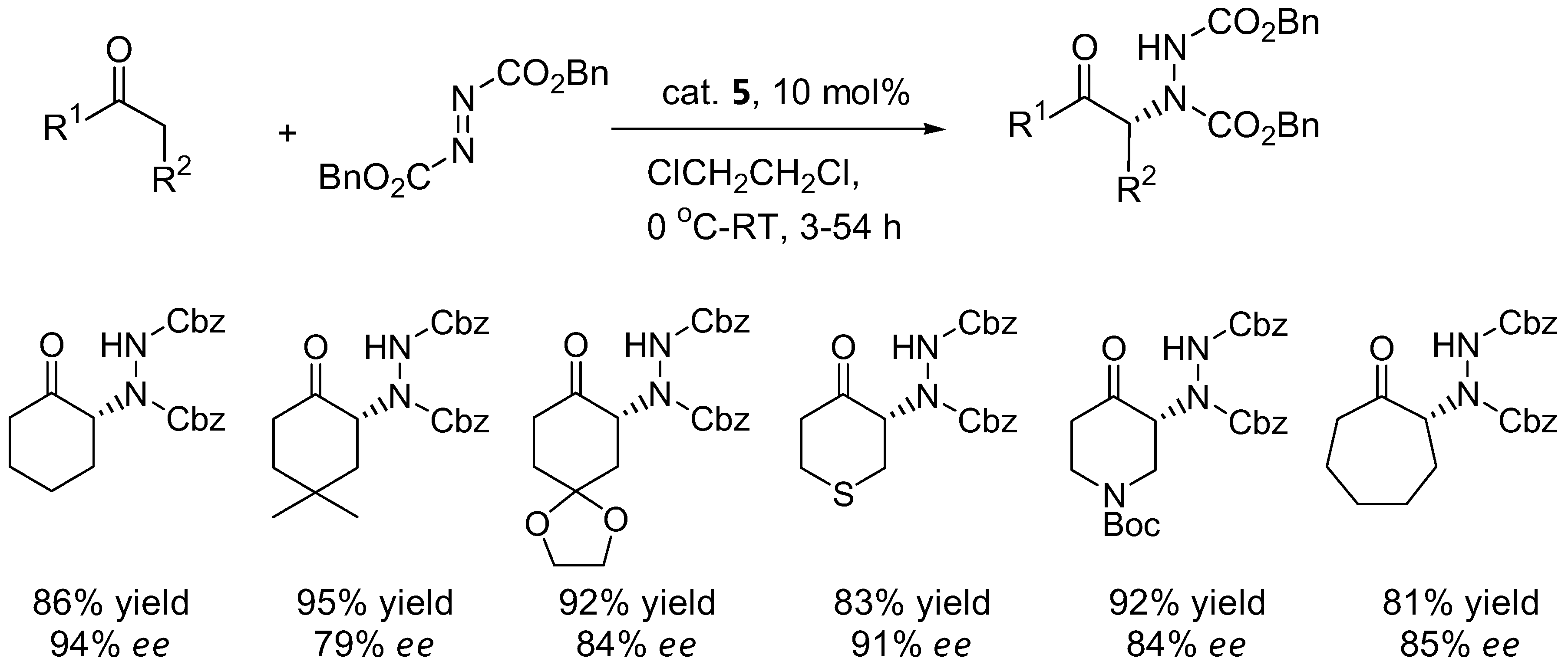

| ketone | R | cat. | conditions | yielda (%) | eeb (%) | ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X=CH2 | Bn | 3 | 20 mol% cat., CH2Cl2, 25 ºC , 24 h | 60 (56) | 90 (61) | [27] |

| X=CH2 | Bn | 4 | 10 mol% cat./TFA, CH2Cl2, 20 ºC, 24 h | 92 (88) | 66 (84) | [28] |

| X=SiPh2 | Bn | 4 | 20 mol% cat./TFA, CH2Cl2, 20 ºC, 24 h | 65 (85) | 71 (60) | [28] |

| X=CH2 | Et | 5 | 10 mol%, ClCH2CH2Cl, RT, 1.5–3 h | 89 (31) | 85 (85) | [29] |

| X=CH2 | Bn | 5 | 10 mol%, ClCH2CH2Cl, RT, 1.5–3 h | 86 (50) | 94 (75) | [29] |

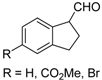

2.1.2. Other carbonyl substrates

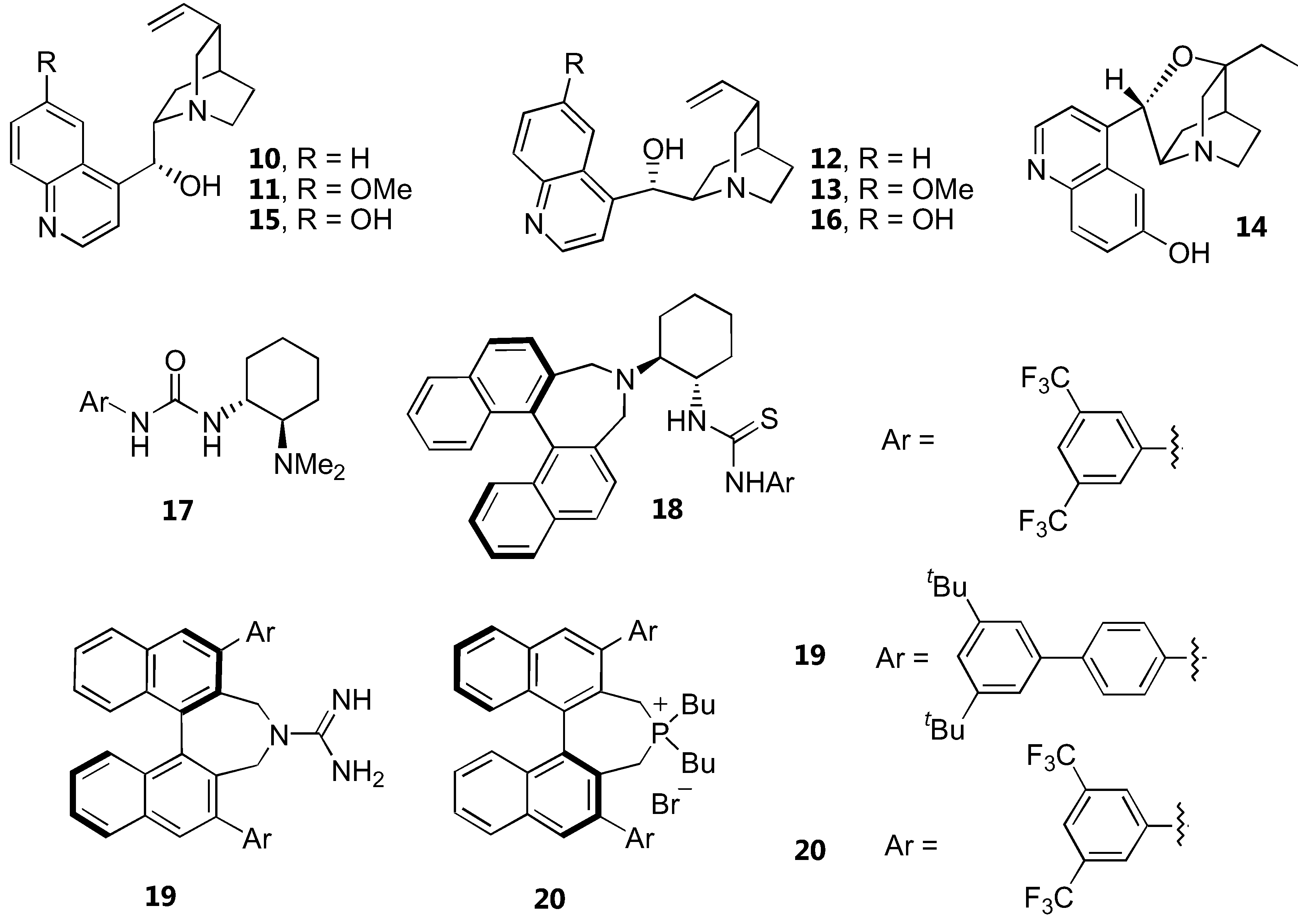

Aromatic ketones

Dicarbonyl compounds

| Cat. | 1,3-Dicarbonylcompounds | Conditions | Yield(%) | ee(%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | acyclic β-keto esters | 20 mol% cat., -25 ºC, 7 d | 72 | 47 | [36] |

| 12 | acyclic β-keto esters | 20 mol% cat., -25 ºC, 7 d | 72 | 27 | [36] |

| 10 | cyclic β-keto esters | 20 mol% cat., -25 ºC, 2 min – 48 h | 92–95 | 54–88 | [36] |

| 12 | cyclic β-keto esters | 20 mol% cat., -25 ºC, 5 min – 24 h | 81–95 | 77–87 | [36] |

| 10 | cyclic β-keto lactones | 20 mol% cat., -25 ºC, 2 min – 4 d | 68–91 | 49–60 | [36] |

| 12 | cyclic β-keto lactones | 20 mol% cat., -25 ºC, 2 min – 4 d | 51–96 | 42–57 | [36] |

| 14 | acyclic and cyclic β-keto esters | 5 mol% cat., -52ºC –RT, toluene, 16–143 h | 86–99 | 83–90 | [37] |

| 15 or 16 | acyclic β-keto thioesters | 0.5–10 mol% cat., -78 ºC to RT, 5 min–3 h | 91–95 | 90–>99 | [38] |

| 17 | cyclic β-keto esters | 10 mol% cat., toluene, -78 ºC to RT, 0.5–48 h | 84–98 | 50–92 | [17] |

| 18 | cyclic β-keto esters | 10 mol% cat., toluene, -70 to -30ºC | 85–95 | 93–99 | [14] |

| 19 | cyclic β-keto esters | 0.05–2 mol% cat., THF, -60 ºC, 0.5–24 h | >99 | 97–98 | [15] |

| 19 | acyclic β-keto esters | 2 mol% cat., THF, -60 ºC, 0.5–24 h | 54–>99 | 62–85 | [15] |

| 19 | cyclic β-diketones | 2 mol% cat., THF, -60 ºC, 0.5–24 h | ≥99 | 15–91 | [15] |

| 20 | cyclic β-keto esters | 3 mol% cat., K2CO3 or K2HPO4, toluene, -20 to -40 ºC, 2–96 h | 97–99 | 77–95 | [16] |

| 20 | tert-butyl α-fluoro-benzoylacetate | 3 mol% cat., K2HPO4, toluene, -20 ºC, 84 h | 99 | 73 | [16] |

| 20 | functionalized cyclic diketone | 5 mol% cat., K2HPO4, toluene, -20 ºC, 84 h | 75 | 88 | [16] |

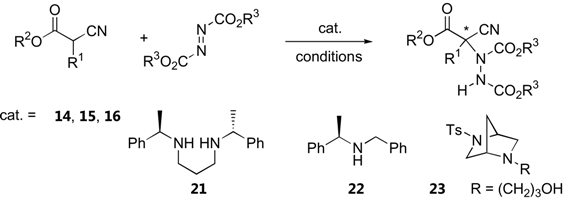

α-Substituted α-cyanoacetates and α-cyanoketones

| Cat. | R1 | R2 | R3 | Conditions | Yield (%) | ee(%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14 | Ph, subst. Ph, 2-Naph, 2-thienyl | tBu | tBu | 5 mol% cat., toluene, -50 to -78 °C, 16–20 h | 95–99 | 89–>98 | [37] |

| 15 | Ph, subst. Ph,1-Naph | Et | tBu, Bn | 5–10 mol% cat., -78 °C, toluene, 1 min–12 h | 72–98 | 87–99 | [40] |

| 16 | Ph, subst. Ph, 1-Naph | Et | tBu, Bn | 5–10 mol% cat., -78 °C, toluene, 1 min–12 h | 71–99 | 82–95 | [40] |

| 15 | Me | CF3CH2 | tBu | 10 mol% cat., toluene, -60 °C | 99(74)a | 91(23)a | [38,40] |

| 16 | Me | CF3CH2 | tBu | 10 mol% cat., toluene, -60 °C | 99(75)a | 81(35)a | [38,40] |

| 18 | Ph | Et | Et | 10 mol% cat., toluene, RT, 1 h | 86 | 65 | [43] |

| 21 | Ph | Et | tBu | 50 mol% cat., 100 °C, 1:1 toluene:hexane, 30 min | 91 | 84( R) | [41] |

| 22 | Ph | Et | tBu | 1–50 mol% cat., -100 °C 1:1 toluene:hexane, 0.5-20 h | 90–95 | 64–80( S) | [41] |

| 23 | Ph | Et | tBu | 25 mol% cat., toluene, -78 °C, 24 h | 76 | 40( R) | [42] |

Miscellaneous substrates

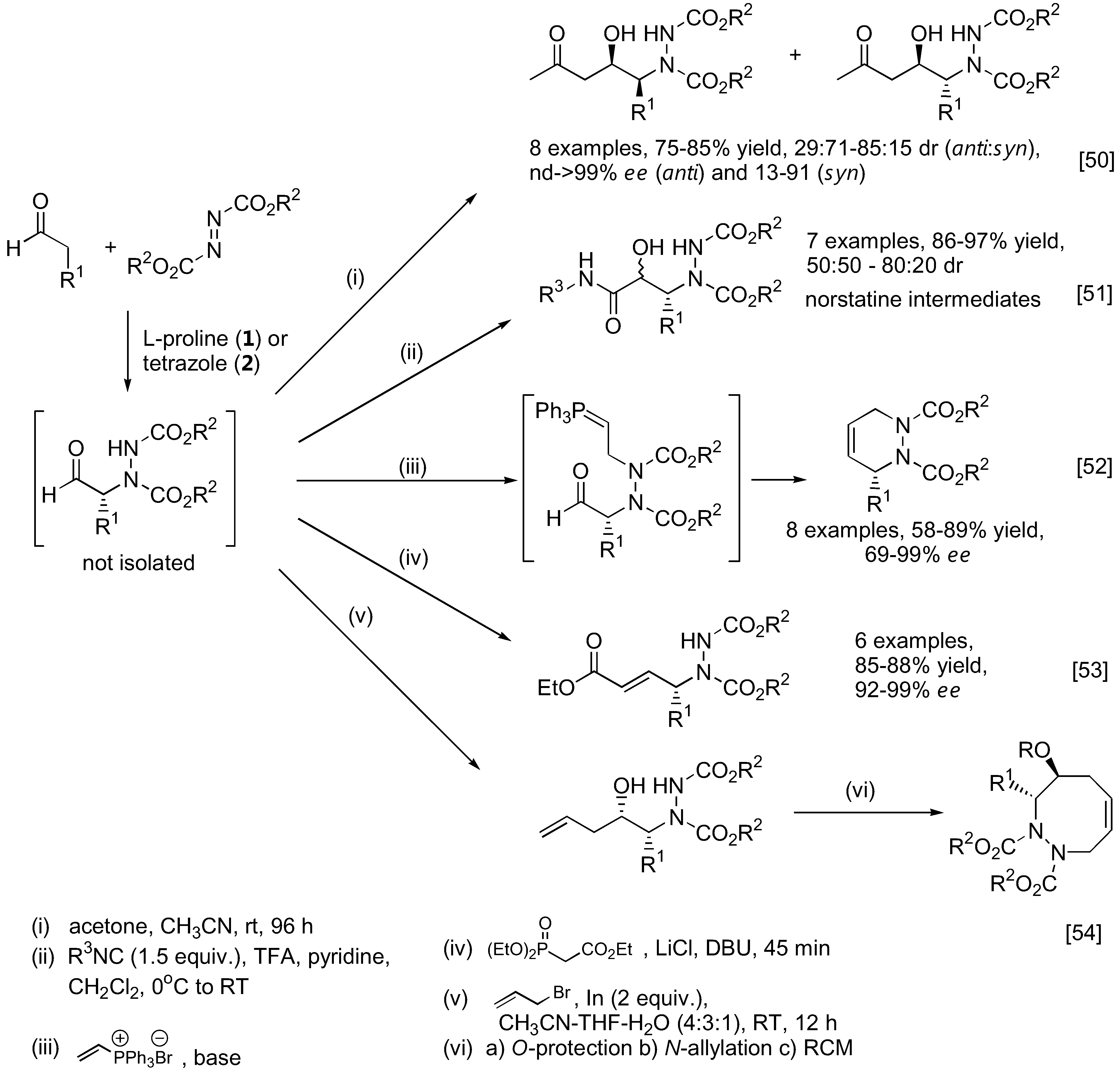

2.1.3. Applications

2.2. α-Sulfamidation

2.3. α-Hydroxyamination

3. α-Aminoxylation Reactions

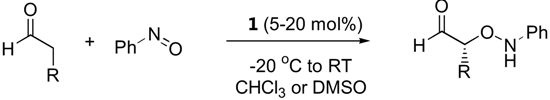

3.1. α-Aminoxylation with nitrosobenzene

3.1.1. Substrates

| R | conditions | yield (%)a | ee (%)a | ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Me, Et, nPr, iPr, Ph, Bn | 30 mol% 1, MeCN, -20 ºC, 24 h | 62–>99 | 95–99 | [62] |

| Me, nBu, iPr, allyl, Bn, Ph, TIPSO(CH2)3, N-methylindol-3-ylmethyl | 5 mol% 1, CHCl3, 4 ºC, 4 h | 60–88 | 97–99 | [63] |

| Me, nPr, iPr, nBu, allyl, Bn, BnOCH2, BocNH(CH2)4 | 20 mol% 1, DMSO, RT, 10–20 min | 54–86 | 94–99 | [64] |

3.1.2. Catalysts

| Cat. | Substrates a | Conditions | Yield (%) | ee (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | ketones (7) | 10 mol% cat., DMF, | 45–76 | 98–>99 | [79] |

| α-unbranched aldehydes (2) | 0 ºC, a few hours | ||||

| 28 | ketones (4) | 20 mol% cat., DMSO, RT | 66–94 | 97–>99 | [80] |

| α-unbranched aldehydes (5) | |||||

| 29 | cyclic ketones (4) | 10 mol% cat., DMSO, RT | 23–80 | 96–>99 | [82] |

| α-unbranched aldehydes (1) | |||||

| 30 | α-unbranched | 20 mol% cat., H2O, | 74–88 | 93–>99 | [81] |

| aldehydes (11) | 2 equiv Bu4NBr, 0 ºC–> RT | ||||

| 31 | α-unbranched aldehydes (3) | 5 mol% cat., toluene, 0 ºC | 69–89 | 86–88 | [83] |

| 32 | α-unbranched aldehydes (7) | 0.2–5 mol% cat., CHCl3, | 86–96 | 97–>98 | [84] |

| 0 ºC –> RT | |||||

| 33 | cyclic 1,3-diketones (5) | 1 mol% cat., benzene, 4 ºC | 49–88 | 68–>98 | [86] |

| cyclic β-ketoesters (11) |

3.1.3. Applications

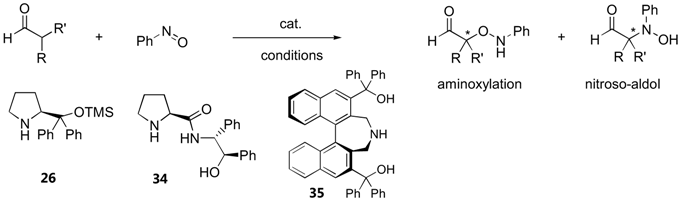

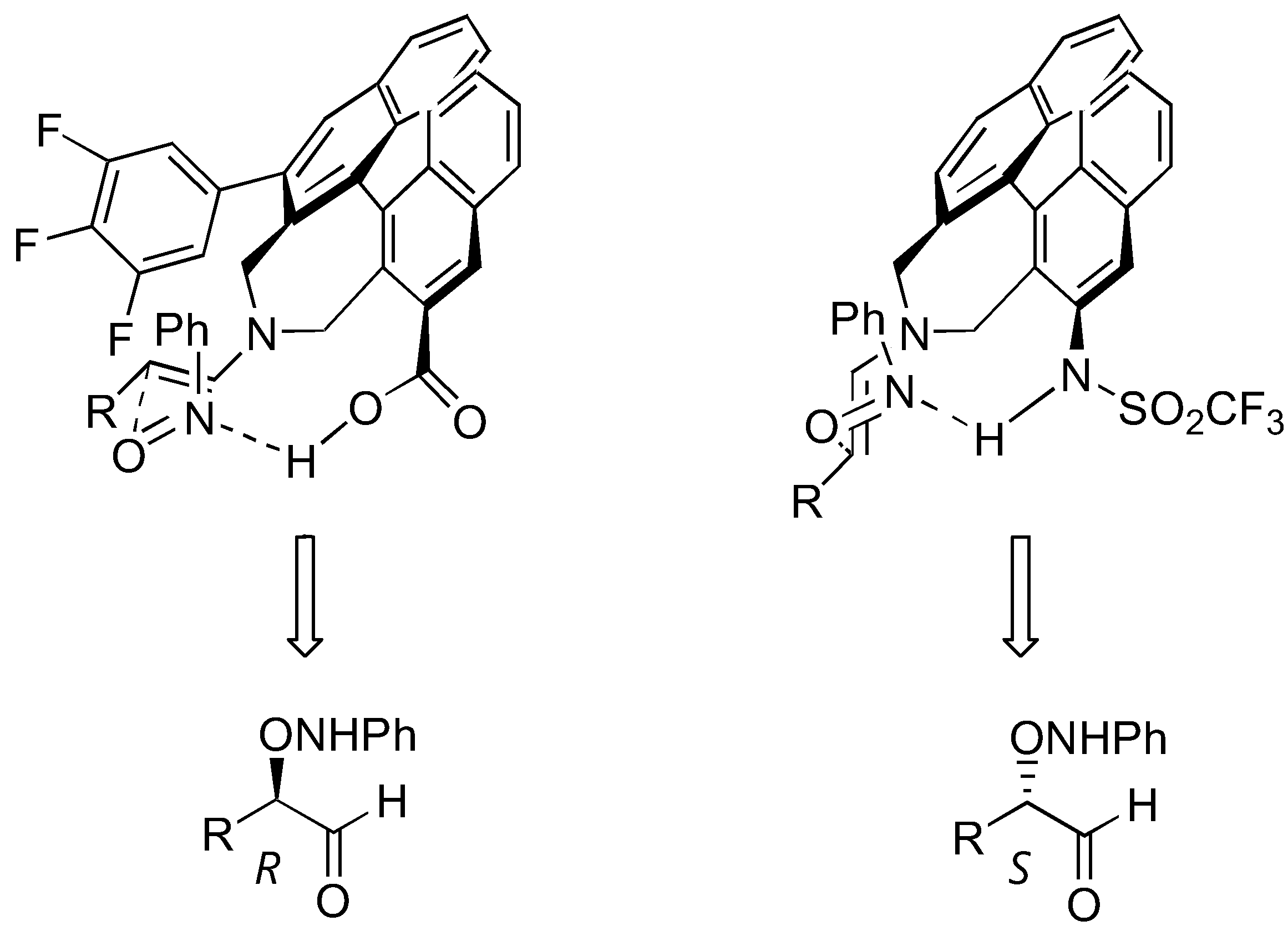

3.1.4. α-Aminoxylation vs. nitrosoaldol reactions

| Cat. | Substratea | Conditions | Yield (%) | ee (%)b | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2-methyl-3-propanal | 20 mol% cat., DMF, | 32 | 67 | [114] |

| 25 ºC, 24 h | (N:O = 1.5:1) | ||||

| 2 | α-branched aldehydes (10) | 20 mol% cat., DMF, | 55–96 | 5–90 | [114] |

| 0–25 ºC , 3–24 h | (N:O = 0.6:1–20:1) | ||||

| 34 | α-branched aldehydes (5) | 10 mol% cat., toluene, | 53–74 | 46–59 | [115] |

| -40 ºC, 2–3 d | (N:O = N/A) | ||||

| 26 | α-unbranched aldehydes (8) | 20 mol% cat., CH2Cl2, | 40–75 | 91–99 | [116] |

| 0 ºC | (N:O >99:1) | ||||

| 35 | α-unbranched aldehydes (6) | 10 mol% cat., THF, | 70–90 | 96–99 | [117] |

| 0 ºC, 1 h | (N:O >99:1) |

3.2. α-Aminoxylation reactions with TEMPO

4. α-Oxidation Reactions

4.1. α-Oxybenzoylation

4.2. α-Oxidation with molecular oxygen

4.3. α-Oxidation with hydroperoxides

4.4. α-Aryloxylation with o-quinones

4.5. α-Oxidation with oxaziridine and iodosobenzene

4.6. α-Oxysulfonation catalyzed by iodoarenes

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Acknowledgements

References and Notes

- Merino, P.; Tejero, T. Organocatalyzed asymmetric α-aminoxylation of aldehydes and ketones - An efficient access to enantiomerically pure α-hydroxycarbonyl compounds, diols, and even amino alcohols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 2995–2997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janey, J.M. Recent advances in catalytic, enantioselective α aminations and α oxygenations of carbonyl compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 4292–4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marigo, M.; Jørgensen, K.A. Organocatalytic direct asymmetric α-heteroatom functionalization of aldehydes and ketones. Chem. Commun. 2006, 2001–2011. [Google Scholar]

- Guillena, G.; Ramón, D.J. Enantioselective α-heterofunctionalisation of carbonyl compounds: organocatalysis is the simplest approach. Tetrahedron-Asymmetr 2006, 17, 1465–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marigo, M.; Jørgensen, K.A. Enamine Catalysis. In Enantioselective Organocatalysis: Reactions and Experimental Procedures; Dalko, P.I., Ed.; Wiley VCH Verlag: Weinheim, Germany, 2007; pp. 56–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kotsuki, H.; Ikishima, H.; Okuyama, A. Organocatalytic asymmetric synthesis using proline and related molecules. Part 2. Heterocycles 2008, 75, 757–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, T.; Maruoka, K. Design of chiral bifunctional secondary amine catalysts for asymmetric enamine catalysis. Chem. Commun. 2008, 5465–6473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-C. The development of asymmetric primary amine catalysts based on cinchona alkaloids. Synlett 2008, 1919–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, H.; Momiyama, N. Rich chemistry of nitroso compounds. Chem. Commun. 2005, 3514–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, H.; Kawasaki, M. Nitroso and azo compounds in modern organic synthesis: Late blooming but very rich. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2007, 80, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, D.; Grondal, C.; Hüttl, R.M. Asymmetric organocatalytic domino reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 1570–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bøgevig, A.; Juhl, K.; Kumaragurubaran, N.; Zhuang, W.; Jørgensen, K.A. Direct organo-catalytic asymmetric α-amination of aldehydes–A simple approach to optically active α-amino aldehydes, α-amino alcohols, and α-amino acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 1790–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List, B. Direct catalytic asymmetric α-amination of aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 5656–5657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.H.; Kim, D.Y. Catalytic enantioselective electrophilic α-hydrazination of β-ketoesters using bifunctional organocatalysts. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 5527–5530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terada, M.; Nakano, M.; Ube, H. Axially chiral guanidine as highly active and enantioselective catalyst for electrophilic amination of unsymmetrically substituted 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 16044–16045. [Google Scholar]

- He, R.; Wang, X.; Hashimoto, T.; Maruoka, K. Binaphthyl-modified quaternary phosphonium salts as chiral phase-transfer catalysts: Asymmetric amination of β-keto esters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 9466–9468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yabuta, T.; Yuan, P.; Takemoto, Y. Organocatalytic enantioselective hydrazination of 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds: Asymmetric synthesis of α,α-disubstituted α-amino acids. Synlett 2006, 137–140. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlin, N.; Bøgevig, A.; Adolfsson, H. N-Arenesulfonyl-2-aminomethylpyrrolidines - Novel modular ligands and organocatalysts for asymmetric catalysis. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2004, 346, 1101–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzén, J.; Marigo, M.; Fielenbach, D.; Wabnitz, T.; Kjærsgaard, A.; Jørgensen, K.A. A general organocatalyst for direct α-functionalization of aldehydes: Stereoselective C-C, C-N, C-F, C-Br, and C-S bond-forming reactions. Scope and mechanistic insights. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 18296–18304. [Google Scholar]

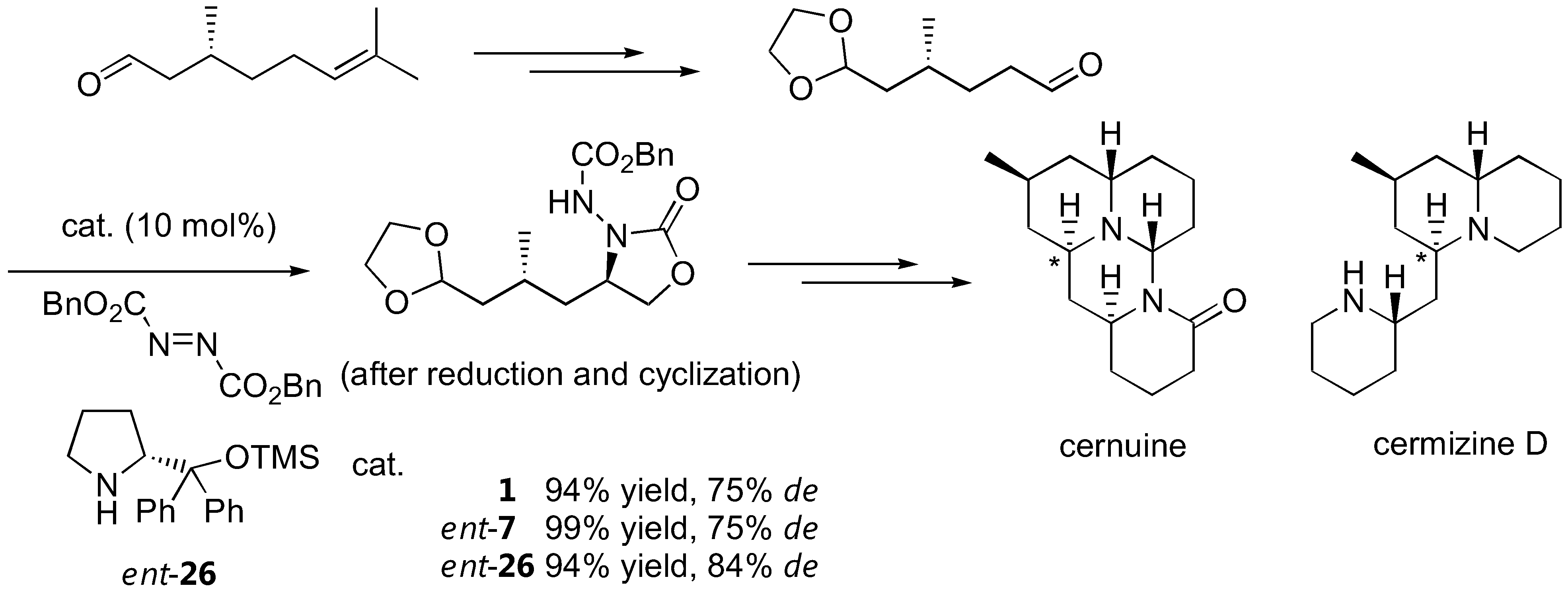

- Nishikawa, Y.; Kitajima, M.; Takayama, H. First asymmetric total syntheses of cernuane-type Lycopodium alkaloids, cernuine, and cermizine D. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 1987–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, H.; Vanderheiden, S.; Bräse, S. Proline-catalysed asymmetric amination of α,α-disubstituted aldehydes: synthesis of configurationally stable enantioenriched α-aminoaldehydes. Chem. Commun. 2003, 2448–2449. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, T.; Vogt, H.; Bräse, S. The proline-catalyzed asymmetric amination of branched aldehydes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 266–282. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdari, N.S.; Barbas, C.F. III, Total synthesis of LFA-1 antagonist BIRT-377 via organocatalytic asymmetric construction of a quaternary stereocenter. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 867–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, T.; Bächle, M.; Hartmann, C.; Bräse, S. Thermal effects in the organocatalytic asymmetric α-amination of disubstituted aldehydes with azodicarboxylates: A high-temperature organocatalysis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 2207–2212. [Google Scholar]

- Suri, J.T.; Steiner, D.; Barbas, C.F. III Organocatalytic enantioselective synthesis of metabotropic glutamate receptor ligands. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 3885–3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaragurubaran, N.; Juhl, K.; Zhuang, W.; Bøgevig, A.; Jørgensen, K.A. Direct L-proline-catalyzed asymmetric α-amination of ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 6254–6255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomassigny, C.; Prim, D.; Greck, C. Amino acid-catalyzed asymmetric α-amination of carbonyls. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 1117–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacoste, E.; Vaique, E.; Berlande, M.; Pianet, I.; Vincent, J.-M.; Landais, Y. Benzimidazole-pyrrolidine/H+ (BIP/H+), a highly reactive organocatalyst for asymmetric processes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 167–177. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, Y.; Aratake, S.; Imai, Y.; Hibino, K.; Chen, Q.-Y.; Yamaguchi, J.; Uchimaru, T. Direct asymmetric α-amination of cyclic ketones catalyzed by siloxyproline. Chem. Asian J. 2008, 3, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotrusz, P.; Alemayehu, S.; Toma, Š.; Schmalz, H.-G.; Adler, A. Enantioselective organocatalysis in ionic liquids: Addition of aliphatic aldehydes and ketones to diethyl azodicarboxylate. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 4904–4911. [Google Scholar]

- Dinér, P.; Kjærsgaard, A.; Lie, M.A.; Jørgensen, K.A. On the origin of the stereoselectivity in organocatalysed reactions with trimethylsilyl-protected diarylprolinol. Chem. Eur. J. 2008, 14, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamura, H.; Methew, H.P.; Blackmond, D.G. In situ catalyst improvement in the proline-mediated α-amination of aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 11770–11771. [Google Scholar]

- Iwamura, H.; Wells, D.H.; Mathew, S.P.; Klussmann, M.; Armstrong, A.; Blackmond, D.G. Probing the active catalyst in product-accelerated proline-mediated reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 16312–16313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, S.P.; Klussmann, M.; Iwamara, H.; Wells, D.H., Jr.; Armstrong, A.; Blackmond, D.G. A mechanistic rationalization of unusual kinetic behavior in proline-mediated C-O and C-N bond-forming reactions. Chem. Commun. 2006, 4291–4293. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.-Y.; Cui, H.-L.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, K.; Du, W.; He, Z.-Q.; Chen, Y.C. Organocatalytic and highly enantioselective direct α-amination of aromatic ketones. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 3671–3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihko, P.M.; Pohjakallio, A. Enantioselective organocatalytic Diels aminations: α-Aminations of cyclic β-keto esters and β-keto lactones with cinchonidine and cinchonine. Synlett 2004, 2115–2118. [Google Scholar]

- Saaby, S.; Bella, M.; Jørgensen, K.A. Asymmetric construction of quaternary stereocenters by direct organocatalytic amination of α-substituted α-cyanoacetates and β-dicarbonyl compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 8120–8121. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Sun, B.; Deng, L. Catalytic enantioselective electrophilic aminations of acyclic α-alkyl β-carbonyl nucleophiles. Synlett 2009, 1685–1689. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, R.; Zhang, D.; Wu, J.; Liu, C. Theoretical study on the enantioselective α-amination reaction of 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds catalyzed by a bifunctional-urea. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2007, 18, 1655–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, H.; Deng, L. Highly enantioselective amination of α-substituted α-cyanoacetates with chiral catalysts accessible from both quinine and quinidine. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 167–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Melgar-Fernández, Juaristi, E. Enantioselective amination of α-phenyl-α-cyanoacetate catalyzed by chiral amines incorporating the α-phenylethyl auxiliary. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 1522–1525. [Google Scholar]

- Melgar-Fernández, R.; González-Olvera, R.; Olivares-Romero, J.L.; González-López, V.; Romero-Ponce, L.; Ramírez-Zárate, M.R.; Demare, P.; Regla, I.; Juaristi, E. Synthesis of novel derivatives of (1S,4S)-2,5-diazabicyclo[2.2.1]heptane and their evaluation as potential ligands in asymmetric catalysis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 655–672. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.M.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, D.Y. Enantioselective Direct amination of α-cyanoketones catalyzed by bifunctional organocatalysts. Synlett 2008, 2659–2662. [Google Scholar]

- Ait-Youcef, R.; Sbargoud, K.; Moreau, X.; Greck, C. Asymmetric α-amination of chiral protected β-hydroxyaldehydes catalyzed by proline. Synlett 2009, 3007–3010. [Google Scholar]

- Ait-Youcef, R.; Kalch, D.; Moreau, X.; Greck, C. Asymmetric α-amination of aldehydes and ketones catalyzed by tert-butoxy-L-proline. Lett. Org. Chem. 2009, 6, 377–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Liu, L.; Wang, D.; Chen, Y.-J. Highly enantioselective and organocatalytic α-amination of 2-oxindoles. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 3874–3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.; Borregan, M.; Barbas, C.F., III J. Expanding the scope of cinchona alkaloid-catalyzed enantioselective α-aminations of oxindoles: A versatile approach to optically active 3-amino-2-oxindole derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 8935–8938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelsen, S.; Marigo, M.; Brandes, S.; Dinér, P.; Jørgensen, K.A. Dienamine catalysis: Organocatalytic asymmetric γ-amination of α,β unsaturated aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 12973–12980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulsen, T.B.; Alemparte, C.; Jørgensen, K.A. Enantioselective organocatalytic allylic amination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 11614–11615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdari, N.S.; Ramachary, D.B.; Barbas III, C.F. Organocatalytic asymmetric assembly reactions: One-pot synthesis of functionalized β-amino alcohols from aldehydes, ketones, and azodicarboxylates. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 1685–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umbreen, S.; Brockhaus, M.; Ehrenberg, H.; Schmidt, B. Norstatines from aldehydes by sequential organocatalytic α-amination and Passerini reaction. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 4585–4595. [Google Scholar]

- Oelke, A.J.; Kumarn, S.; Longbottom, D.A.; Ley, S.V. An enantioselective organocatalytic route to chiral 3,6-dihydropyridazines from aldehydes. Synlett 2006, 2548–2552. [Google Scholar]

- Kotkar, S.P.; Chavan, V.B.; Sudalai, A. Organocatalytic sequential α-amination-Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons olefination of aldehydes: Enantioselective synthesis of γ-amino-α,β-unsaturated esters. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 1001–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, A.; Choi, J.H.; Tae, J. Organocatalytic α-amination-allylation-RCM strategy: enantioselective synthesis of cyclic hydrazines. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 4882–4885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marigo, M.; Schulte, T.; Franzén; Jørgensen, K.A. Asymmetric multicomponent domino reactions and highly enantioselective conjugated addition of thiols to α,β-unsaturated aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 15710–15711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Nielsen, J.B.; Nielsen, M.; Jørgensen, K.A. Organocatalysed asymmetric β-amination and multicomponent syn-selective diamination of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes. Chem. Eur. J. 2007, 13, 9068–9075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Figueiredo, R.M.; Christmann, M. Organocatalytic synthesis of drugs and bioactive natural products. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 2575–2600. [Google Scholar]

- Kalch, D.; De Rycke, N.; Mareau, X.; Greck, C. Efficient syntheses of enantioenriched (R)-pipecolic acid and (R)-proline via electrophilic organocatalytic amination. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 492–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouthaiwale, P.V.; Kotkar, S.P.; Sudalai, A. Formal synthesis of (-)anisomycin via organocatalysis. ARKIVOC 2009, ii, 88–94. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, C.E.; Gross, P.J.; Nieger, M.; Bräse, S. Towards an asymmetric synthesis of the bacterial peptide deformylase (PDF) inhibitor fumimycin. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2009, 7, 5059–5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, H.; Baumann, R.; Nieger, M.; Bräse, S. Direct asymmetric α-sulfamidation of α-branched aldehydes: A novel approach to enamine catalysis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 5315–5338. [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, Y.; Yamaguchi, J.; Hibino, K.; Shoji, M. Direct proline catalyzed asymmetric α-aminooxylation of aldehydes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 8293–8296. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.P.; Brochu, M.P.; Sinz, C.J.; MacMillan, D.W.C. The direct and enantioselective organocatalytic α-oxidation of aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 10808–10809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, G. A facile and rapid route to highly enantiopure 1,2-diols by novel catalytic asymmetric α-aminoxylation of aldehydes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 4247–4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bøgevig, A.; Sundén, H.; Córdova, A. Direct catalytic enantioselective α-aminoxylation of ketones: A stereoselective synthesis of α-hydroxy and α,α'-dihydroxy ketones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 1109–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, Y.; Yamaguchi, J.; Sumiya, T.; Shoji, M. Direct proline-catalyzed asymmetric α-aminoxylation of ketones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 1112–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdova, A.; Sundén, H.; Bøgevig, A.; Johannson, M.; Himo, F. The direct catalytic asymmetric α-aminooxylation reaction: Development of stereoselective routes to 1,2-diols and 1,2-amino alcohols and density functional calculations. Chem. Eur. J. 2004, 10, 3673–3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, Y.; Yamaguchi, J.; Sumiya, T.; Hibino, K.; Shoji, M. Direct proline-catalyzed asymmetric α-aminoxylation of aldehydes and ketones. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 5966–5973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momiyama, N.; Torii, H.; Yamamoto, H. O-Nitroso aldol synthesis: Catalytic enantioselective route to α-aminooxy carbonyl compounds via enamine intermediate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 5374–5378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachary, D.B.; Barbas, C.F. III Direct amino acid-catalyzed asymmetric desymmetrization of meso-compounds: Tandem aminoxylation/O-N bond heterolysis reactions. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 1577–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J.; Ramachary, D.B.; Jemmis, E.D. Electrostatic repulsion as an additional selectivity factor in asymmetric proline catalysis. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006, 4, 2685–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

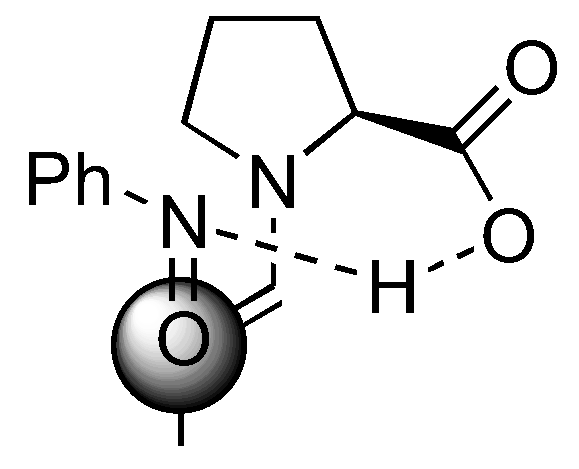

- Font, D.; Bastero, A.; Sayalero, S.; Jimeno, C.; Pericàs, M.A. Highly enantioselective α-aminoxylation of aldehydes and ketones with a polymer-supported organocatalyst. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 1943–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Huang, Z.-Z.; Li, X.-L. Highly enantioselective α-aminoxylation of aldehydes and ketones in ionic liquids. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 8320–8323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.-M.; Niu, H.-Y.; Xue, M.-X.; Guo, Q.-X.; Cun, L.-F.; Mi, A.-Q.; Jiang, Y.-Z.; Wang, J.-J. L-Proline in an ionic liquid as an efficient and reusable catalyst for direct asymmetric α-aminoxylation of aldehydes and ketones. Green Chem. 2006, 8, 682–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, P. H.-Y.; Houk, K.N. Origins of selectivities in proline-catalyzed α-aminoxylations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 13912–13913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, S.P.; Iwamura, H.; Blackmond, D.G. Amplification of enantiomeric excess in a proline-mediated reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 3317–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poe, S.L.; Bogdan, A.R.; Mason, B.P.; Steinbacher, J.L.; Opalka, S.M.; McQuade, D.T. Use of bifunctional ureas to increase the rate of proline-catalyzed α-aminoxylations. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 1574–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zotova, N.; Moran, A.; Armstrong, A.; Blackmond, D.G. A coherent mechanistic rationale for additive effects and autoinductive behaviour in proline-mediated reactions. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009, 351, 2765–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, Y.; Yamaguchi, J.; Hibino, K.; Sumiya, T.; Urushima, T.; Shoji, M.; Hashizume, D.; Koshino, H. A highly active 4-siloxyproline catalyst for asymmetric synthesis. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2004, 346, 1435–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Liao, L. An amine sulfonamide organocatalyst for promoting direct, highly enantioselective α-aminoxylation reactions of aldehydes and ketones. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 7235–7238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, P.J.; Tan, B.; Zhong, G. Highly enantioselective L-thiaproline catalyzed α-aminoxylation of aldehydes in aqueous media. Green Chem. 2009, 11, 543–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundén, H.; Dahlin, N.; Ibrahem, I.; Adolfsson, H.; Córdova, A. Novel organic catalysts for the direct enantioselective α-oxidation of carbonyl compounds. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 3385–3389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, T.; Yamamoto, A.; Mii, H.; Takai, J.; Shirakawa, S.; Maruoka, K. Direct asymmetric aminoxylation reaction catalyzed by axially chiral amino acids. Chem. Lett. 2008, 37, 250–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, T.; Yamamoto, A.; Maruoka, K. Direct asymmetric aminoxylation reaction catalyzed by a binaphthyl-based chiral amino sulfonamide with high catalytic performance. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 5369–5371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, T.; Yamamoto, A.; Shirozu, F.; Maruoka, K. Enantioselectivity switch in direct asymmetric aminoxylation catalyzed by binaphthyl-based chiral secondary amines. Synthesis 2009, 1557–1563. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, M.; Lu, Y.; Zeng, X.; Tan, B.; Xu, Z.; Zhong, G. Chiral Brønsted acid-catalyzed enantioselective α-hydroxylation of β-dicarbonyl compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 4562–4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

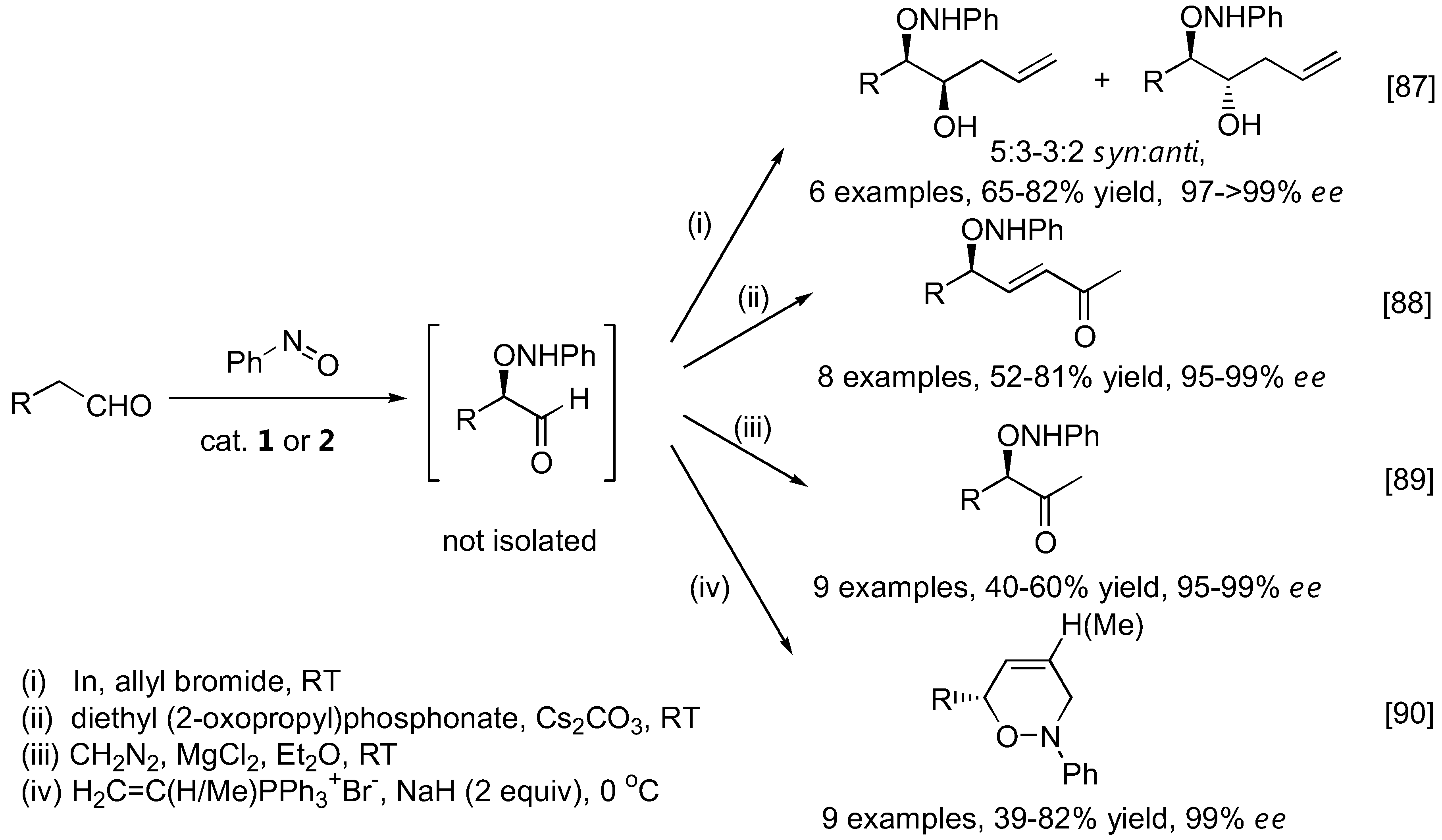

- Zhong, G. Tandem aminoxylation-allylation reactions: a rapid, asymmetric conversion of aldehydes to mono-substituted 1,2-diols. Chem. Commun. 2004, 606–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, G.; Yu, Y. Enantioselective synthesis of allylic alcohols by the sequential aminoxylation-olefination reactions of aldehydes under ambient conditions. Org. Lett. 2004, 6, 1637–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, R.-H.; Wang, B.; Weng, L.-L.; Zheng, H. Asymmetric synthesis of 3-hydroxyl-2-alkanones via tandem organocatalytic aminoxylation of aldehydes and chemoselective diazomethane homologation. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 2628–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumarn, S.; Shaw, D.M.; Longbottom, D.A.; Ley, S.V. A highly selective, organocatalytic route to chiral dihydro-1,2-oxazines. Org. Lett. 2005, 7, 4189–4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumarn, S.; Shaw, D.M.; Ley, S.V. A highly selective, organocatalytic route to chiral 1,2-oxazines from ketones. Chem. Comm. 2006, 3211–3213. [Google Scholar]

- Kumarn, S.; Oelke, A.J.; Shaw, D.M.; Longbottom, D.A.; Ley, S.V. A sequential enantioselective, organocatalytic route to chiral 1,2-oxazines and chiral pyridazines. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007, 5, 2678–2689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

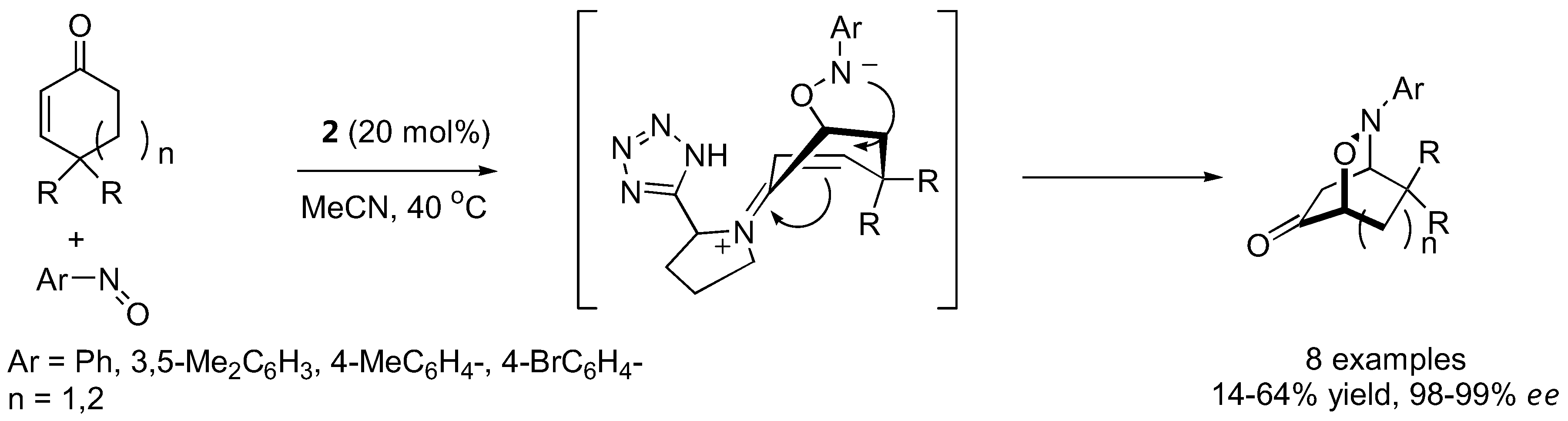

- Yamamoto, Y.; Momiyama, N.; Yamamoto, H. Enantioselective tandem O-nitroso aldol/Michael reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 5962–5963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momiyama, N.; Yamamoto, Y.; Yamamoto, H. Diastereo- and enantioselective synthesis of nitroso Diels-Alder-type bicycloketones using dienamine: Mechanistic insight into sequential nitroso aldol/Michael reaction and application for optically pure 1-amino-3,4-diol synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 1190–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

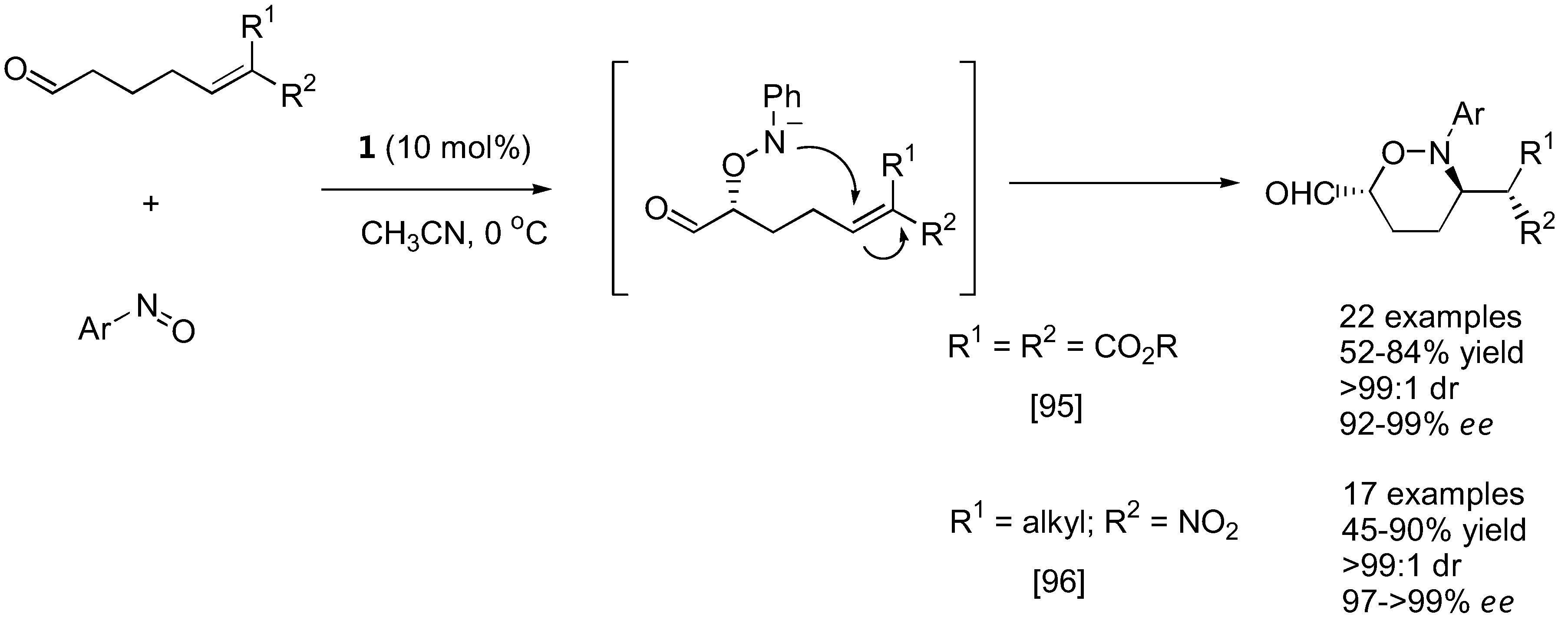

- Zhu, D.; Lu, M.; Chua, P.J.; Tan, B.; Wang, F.; Yang, X.; Zhong, G. A highly stereoselective organocatalytic tandem aminoxylation/aza-Michael reaction for the synthesis of tetrahydro-1,2-oxazines. Org. Lett. 2008, 10, 4585–4588. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, M.; Zhu, D.; Lu, Y.; Hou, Y.; Tan, B.; Zhong, G. Organocatalytic asymmetric α-aminoxylation/aza-Michael reactions for the synthesis of functionalized tetrahydro-1,2-oxazines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 10187–10191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D.; Lu, M.; Dai, L.; Zhong, G. Highly stereoselective one-pot synthesis of bicyclic isoxazolidines with five stereogenic centers by an organocatalytic process. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 6089–6092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondekar, N.B.; Kumar, P. Iterative approach to enantiopure syn/anti-1,3-polyols via proline-catalyzed sequential α-aminoxylation and Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons olefination of aldehydes. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 2611–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, D.; Müller, M. Efficient asymmetric syntheses of (+)-strictifolione. Synthesis 2004, 1486–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, S.; Sudalai, A. Enantioselective synthesis of tarchonanthuslactone using proline-catalyzed asymmetric α-aminooxylation. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2007, 18, 975–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangion, I.K.; MacMillan, D.W.C. Total synthesis of brasoside and littoralisone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 3696–3697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, J.; Toyoshima, M.; Shoji, M.; Kakeya, H.; Osada, H.; Hayashi, Y. Concise enantio- and diastereoselective total syntheses of fumagillol, RK-805, FR65814, ovalicin, and 5-demethylovalicin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 789–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varseev, G.N.; Maier, M.E. Enantioselective total synthesis of (+)-neosymbioimine. Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 1461–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, S.; Makino, K.; Hamada, Y. Total synthesis of halipeptin A, a potent anti-inflammatory cyclodepsipeptide from a marine sponge. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 1081–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-G.; Park, T.-H.; Kim, B. J. Efficient total synthesis of (+)-exo-, (-)-endo-brevicomin and their derivatives via asymmetric organocatalysis and olefin cross-metathesis. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 6369–6372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narina, S.V.; Sudalai, A. Short and practical enantioselective synthesis of linezolid and eperezolid via proline-catalyzed asymmetric α-aminooxylation. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 6799–6802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotkar, S.P.; Sudalai, A. A short enantioselective synthesis of the antiepileptic agent, levetiracetam based on proline-catalyzed asymmetric α-aminooxylation. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 6813–6815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotkar, S.P.; Sudalai, A. Enantioselective synthesis of (S,S)-ethambutol using proline-catalyzed asymmetric α-aminooxylation and α-amination. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2006, 17, 1738–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotkar, S.P.; Suryavanshi, G.S.; Sudalai, A. A short synthesis of (+)-harzialactone A and (R)-(+)-4-hexanolide via proline-catalyzed sequential α-aminooxylation and Horner-Wadsworth-Emmons olefination of aldehydes. Tetrahedron-Asymmetr 2007, 18, 1795–1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talluri, S.K.; Sudalai, A. An organo-catalytic approach to the enantioselective synthesis of (R)-selegiline. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 9758–9763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchgalle, S.P.; Gore, R.G.; Chavan, S.P.; Kalkote, U.R. Organocatalytic enantioselective synthesis of β-blockers: (S)-propranolol and (S)-naftopidil. Tetrahedron-Asymmetr. 2009, 20, 1767–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-G. Concise total synthesis of (+)-disparlure and its trans-isomer using asymmetric organocatalysis. Synthesis 2009, 2418–2422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawant, R.T.; Waghmode, S.B. Organocatalytic enantioselective formal synthesis of HRV 3C-protease inhibitor (1R,3S)-thysanone. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 1599–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-G.; Park, T.-H. Organocatalyzed asymmetric α-hydroxyamination of α-branched aldehydes: Asymmetric synthesis of optically active N-protected α,α-disubstituted amino aldehydes and amino alcohols. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 9067–9071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.-M.; Cheng, L.; Cun, L.-F.; Gong, L.-Z.; Mi, A.-Q.; Jiang, Y.-Z. L-Prolinamide-catalyzed direct nitroso aldol reactions of α-branched aldehydes: A distinct regioselectivity from that with L-proline. Chem. Commun. 2006, 429–431. [Google Scholar]

- Palomo, C.; Vera, S.; Velilla, I.; Mielgo, A.; Gómez-Bengoa, E. Regio- and enantioselective direct oxyamination reaction of aldehydes catalyzed by α,α-diphenylprolinol trimethylsilyl ether. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 8054–8056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, T.; Ueda, M.; Takai, J.; Maruoka, K. Direct asymmetric hydroxyamination reaction catalyzed by an axially chiral secondary amine catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 6046–6047. [Google Scholar]

- Momiyama, N.; Yamamoto, H. Brønsted acid catalysis of achiral enamine for regio- and enantioselective nitroso aldol synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 1080–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Cantarero, J.; Cid, M.B.; Poulsen, T.B.; Bella, M.; Ruano, J.L.G.; Jørgensen, K.A. Intriguing behavior of cinchona alkaloids in the enantioselective organocatalytic hydroxyamination of α-substituted-α-cyanoacetates. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 7062–7065. [Google Scholar]

- Sibi, M.P.; Hasegawa, M. Organocatalysis in radical chemistry. Enantioselective α-oxyamination of aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 4124–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, N.-N.; Ho, X.-H.; Mho, S.I.; Jang, H.-Y. Organocatalyzed α-oxyamination of aldehydes using anodic oxidation. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 5309–5312. [Google Scholar]

- Vaismaa, M.J.P.; Yau, S.C.Y.; Tomkinson, N.C.O. Organocatalytic α-oxybenzoylation of aldehydes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 3625–3627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotoh, H.; Hayashi, Y. Diphenylprolinol silyl ether as a catalyst in an asymmetric, catalytic and direct α-benzoyloxylation of aldehydes. Chem. Commun. 2009, 3083–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kano, T.; Mii, H.; Maruoka, K. Direct asymmetric benzoyloxylation of aldehyde catalyzed by 2-tritylpyrrolidine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 3450–3451. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahem, I.; Zhao, G.-L.; Sundén, H.; Córdova, A. A route to 1,2-diols by enantioselective organocatalytic α-oxidation with molecular oxygen. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 4659–4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdova, A.; Sundén, H.; Engqvist, M.; Ibrahem, I.; Casas, J. The direct amino acid-catalyzed asymmetric incorporation of molecular oxygen to organic compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 8914–8915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acocella, M.R.; Mancheño, O.G.; Bella, M.; Jørgensen, K.A. Organocatalytic asymmetric hydroxylation of β-keto esters: Metal-free synthesis of optically active anti-diols. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 8165–8167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

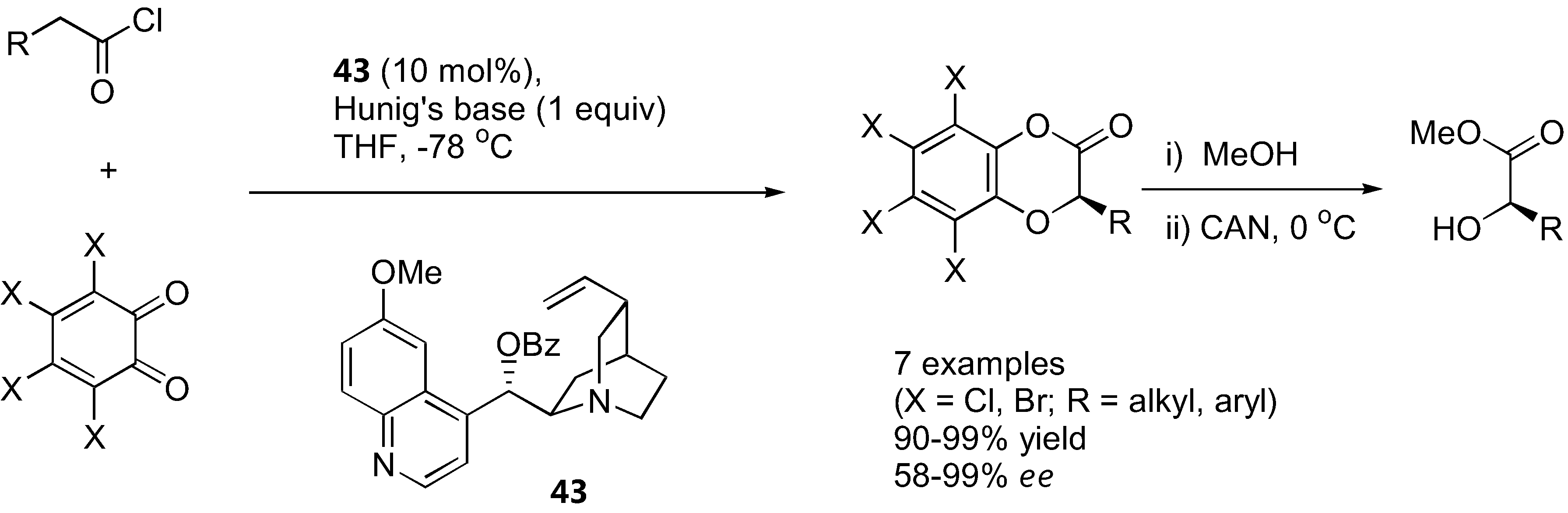

- Bekele, T.; Shah, M.H.; Wolfer, J.; Abraham, C.J.; Weatherwax, A.; Lectka, T. Catalytic, enantioselective [4+2]-cycloadditions of ketene enolates and o-quinones: efficient entry to chiral, α-oxygenated carboxylic acid derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 1810–1811. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Juan, F.A.; Cockfield, D.M.; Dixon, D.J. Enantioselective organocatalytic aryloxylation of aldehydes with o-quinones. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 1605–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engqvist, M.; Casas, J.; Sundén, H.; Ibrahem, I.; Córdova, A. Direct organocatalytic asymmetric α-oxidation of ketones with iodosobenzene and N-sulfonyloxaziridines. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 2053–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.-T.; Brimble, M.A.; Barker, D. Influence of α-methyl substitution of proline-based organocatalysts on the asymmetric α-oxidation of aldehydes. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 4801–4807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, R.D.; Page, T.K.; Altermann, S.; Paradine, S.M.; French, A.N.; Wirth, T. Enantioselective α-oxytosylation of ketones catalysed by iodoarenes. Synlett 2007, 538–542. [Google Scholar]

- Altermann, S.M.; Richardson, R.D.; Page, T.K.; Schmidt, R.K.; Holland, E.; Mohammed, U.; Paradine, S.M.; French, A.N.; Richter, C.; Bahar, A.M.; Witulski, B.; Wirth, T. Catalytic enantioselective α-oxysulfonation of ketones mediated by iodoarenes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 5315–5328. [Google Scholar]

© 2010 by the authors;

Share and Cite

Vilaivan, T.; Bhanthumnavin, W. Organocatalyzed Asymmetric α-Oxidation, α-Aminoxylation and α-Amination of Carbonyl Compounds. Molecules 2010, 15, 917-958. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules15020917

Vilaivan T, Bhanthumnavin W. Organocatalyzed Asymmetric α-Oxidation, α-Aminoxylation and α-Amination of Carbonyl Compounds. Molecules. 2010; 15(2):917-958. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules15020917

Chicago/Turabian StyleVilaivan, Tirayut, and Worawan Bhanthumnavin. 2010. "Organocatalyzed Asymmetric α-Oxidation, α-Aminoxylation and α-Amination of Carbonyl Compounds" Molecules 15, no. 2: 917-958. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules15020917