Nanoporous Materials as New Engineered Catalysts for the Synthesis of Green Fuels

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Thermodynamics of CO2

3. Reaction Mechanism of CO2 Methanation

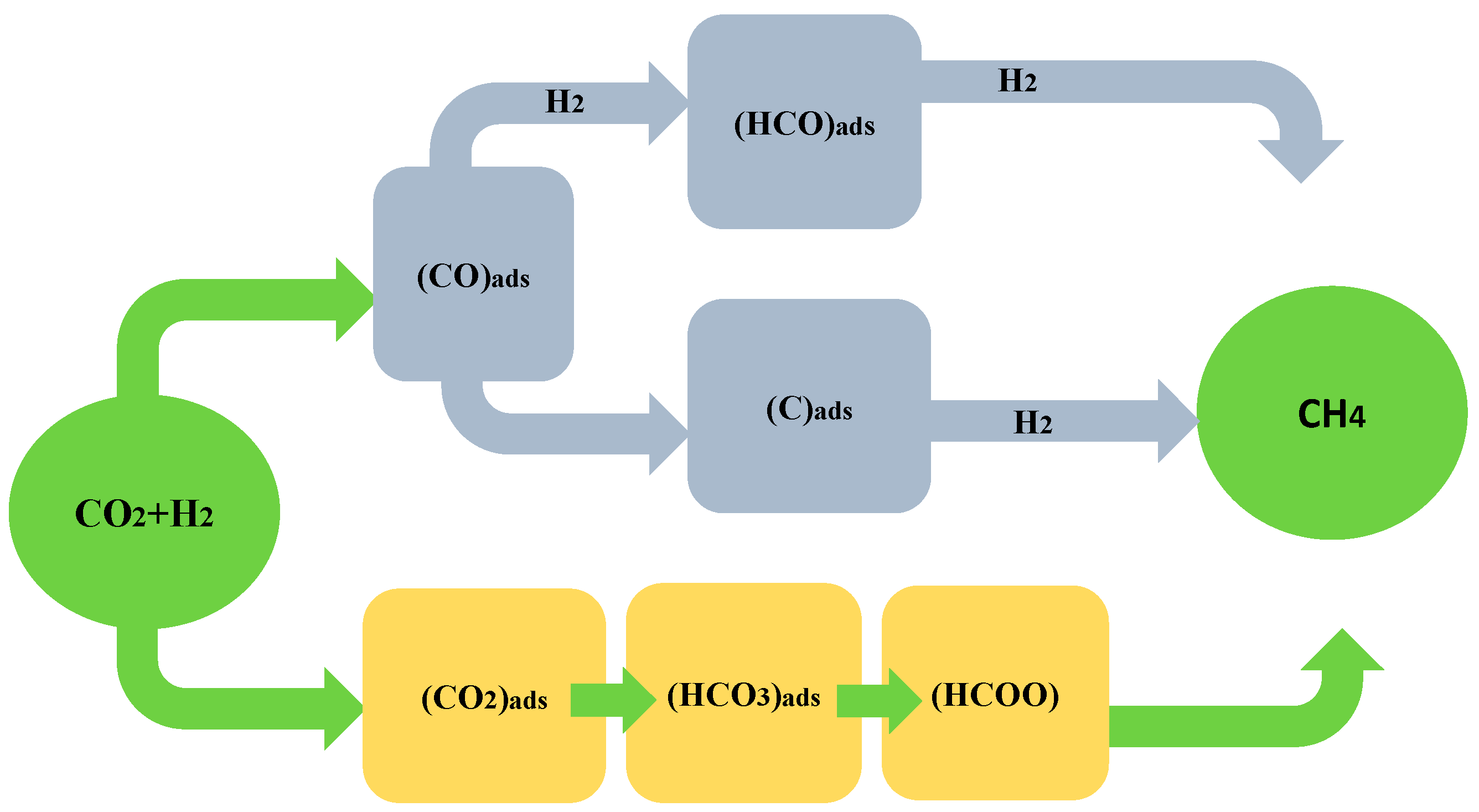

3.1. Methanation of CO2 with CO as Intermediate

3.2. Methanation of CO2 without CO as Intermediate

4. Catalytic Conversion of CO2 to CH4

5. Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 into CH4

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fechete, I.; Wang, Y.; Védrine, J.C. The past, present and future of heterogeneous catalysis. Catal. Today 2012, 189, 2–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aresta, M.; Dibenedetto, A.; Angelini, A. Catalysis for the valorization of exhaust carbon: From CO2 to chemicals, materials, and fuels. Technological use of CO2. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 1709–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiaoding, X.; Moulijn, J.A. Mitigation of CO2 by chemical conversion: Plausible chemical reactions and promising products. Energy Fuels 1996, 10, 305–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centi, G.; Quadrelli, E.A.; Perathoner, S. Catalysis for CO2 conversion: A key technology for rapid introduction of renewable energy in the value chain of chemical industries. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 1711–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.S.; Centi, G.A. Perspective on carbon materials for future energy application. J. Energy Chem. 2013, 22, 151–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normile, D. Carbon Capture and Sequestration. Science 2009, 325, 1642–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Yin, X.; Karpuzov, D.; Semagina, N. PVP-stabilized mono- and bimetallic Ru for selective ring opening. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2013, 3, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, L.; Nassreddine, S.; Toussaint, G.; Geantet, C. Mechanism of tetralin ring opening and contraction over bifunctional Ir/SiO2–Al2O3 catalysts. ChemSusChem 2012, 5, 1717–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fechete, I.; Ersen, O.; Garin, F.; Lazar, L.; Rach, A. Catalytic behavior of MnMCM-48 and WMnMCM-48 ordered mesoporous catalysts in a reductive environment: A study of the conversion of methylcyclopentane. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2013, 3, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicerich, M.A.; Benitez, V.M.; Especel, C.; Epron, F.; Pieck, C.L. Influence of iridium content on the behavior of Pt-Ir/Al2O3 and Pt-Ir/TiO2 catalysts for selective ring opening of naphthenes. Appl. Catal. A 2013, 453, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, S.P.; Ma, X.B.; Gong, J.L. Recent advances in catalytic hydrogenation of carbon dioxide. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 3703–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, B.; Guild, C.; Suib, S.L. Thermal, electrochemical, and photochemical conversion of CO2 to fuels and value-added products. J. CO2 Util. 2013, 1, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoila, P.; Epron, F.; Marecot, P.; Especel, C. Influence of chlorine on the catalytic properties of supported rhodium, iridium and platinum in ring opening of naphthenes. Appl. Catal. A 2013, 462–463, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ippolito, S.A.; Gutierrez, L.B.; Vera, C.R.; Pieck, C.L. Pt-Mg-Ir/Al2O3 and Pt-Ir/HY zeolite catalysts for SRO of decalin. Influence of Ir content and support acidity. Appl. Catal. A 2013, 452, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fechete, I.; Donnio, B.; Ersen, O.; Dintzer, T.; Djeddi, A.; Garin, F. Single crystals of mesoporous tungstenosilicate WMCM-48 molecular sieves for the conversion of methylcyclopentane (MCP). Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 2791–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.; Wu, D.; Tschamber, V.; Fechete, I.; Garin, F. Carbon-NSR catalyst interaction: Impact on catalyst structure and NOx storage efficiency. Appl. Catal. B 2013, 132–133, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omae, I. Aspects of carbon dioxide utilization. Catal. Today 2006, 115, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urda, A.; Popescu, I.; Marcu, I.C.; Carja, G.; Apostolescu, N.; Sandulescu, I. Methane and propane total oxidation on catalysts from FeLDH precursors. Rev. Roum. Chim. 2010, 61, 267–271. [Google Scholar]

- Haddoum, S.; Fechete, I.; Donnio, B.; Garin, F.; Lutic, D.; Chitour, C.E. FeTUD-1 for the preferential rupture of the substituted C-C bond of methylcyclopentane (MCP). Catal. Commun. 2012, 27, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbarino, G.; Riani, P.; Magistri, L.; Busca, G. A study of the methanation of carbon dioxide on Ni/Al2O3 catalysts at atmospheric pressure. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2014, 39, 11557–11565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olajire, A.A. Valorization of greenhouse carbon dioxide emissions into value-added products by catalytic processes. J. CO2 Util. 2013, 3–4, 74–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fechete, I.; Jouikov, V. Double decarbonylation of phthalimide revisited: A facile cathodic synthesis of isoindoline. Electrochim. Acta 2008, 53, 7107–7110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djeddi, A.; Fechete, I.; Garin, F. Selective ring opening of methylcyclopentane over titania-supported monometallic (Pt,Ir) and bimetallic (Pt-Ir) catalysts. Top. Catal. 2012, 55, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aresta, M.; Dibenedetto, A.; Angelini, A. The changing paradigm in CO2 utilization. J. CO2 Util. 2013, 3–4, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, S.; Amin, N.A.S.; Rahimpour, M.R. Hydrogenation of CO2 to value-added products—A review and potential future developments. J. CO2 Util. 2014, 5, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhardt, M.; Busch, G. Methanation of hydrogen and carbon dioxide. Appl. Energy 2013, 111, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Castro, J.; Rivera-Tinoco, R.; Bouallou, C. Hydrogen production from natural gas: Auto-thermal reforming and CO2 capture. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2010, 21, 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Garza, D.; Rivera-Tinoco, R.; Bouallou, A. Comparison of ammonia monoethylamie, diethanolamine and methyldiethanolamine solvents to reduce CO2 greenhouse gas emissions. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2009, 20, 279–284. [Google Scholar]

- Olajire, A.A. CO2 capture and separation technologies for end-of-pipe applications. Energy 2010, 35, 2610–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olajire, A.A. A review of mineral carbonation technology in sequestration of CO2. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2013, 109, 364–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachu, S. CO2 storage in geological media: Role, means, status and barriers to deployment. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2008, 34, 254–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Alphen, K.; Noothout, P.M.; Hekkert, M.P.; Turkenburg, W.C. Evaluating the development of carbon capture and storage technologies in the United States. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 971–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Drese, J.H.; Jones, C.W. Adsorbent materials for carbon dioxide capture from large anthropogenic point sources. ChemSusChem 2009, 2, 796–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goj, A.; Sholl, D.S.; Akten, E.D.; Kohen, D.J. Atomistic simulations of CO2 and N2 adsorption in silica zeolites: The impact of pore size and shape. Phys. Chem. B 2002, 106, 8367–8375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.W.; Sandler, S.I. Separation of CO2 and N2 by adsorption in C168 schwarzite: A combination of 245 quantum mechanics and molecular simulation study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 11989–11997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Smit, B. Comparative molecular simulation study of CO2/N2 and CH2/N2 separation in zeolites and metal–organic frameworks. Langmuir 2009, 25, 5918–5926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudiro, M.; Bertucco, A. Production of synthetic gasoline and diesel fuel by alternative processes using natural gas and coal: Process simulation and optimization. Energy 2009, 34, 2206–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbe, H. Ueber Synthese der Salicylsäure. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1869, 113, 125–127. [Google Scholar]

- Solvay, E. Manufacture of Soda by the Ammonia Process. U.S. Patent 263,981, 5 September 1882. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, G.; Meiser, W. Process of Manufacturing Urea. U.S. Patent 1,429,483, 19 September 1922. [Google Scholar]

- Krier, C.; Hackel, M.; Hägele, C.; Urtel, H.; Querner, C.; Haas, A. Improving the methanation process. Chem. Ing. Tech. 2013, 85, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopyscinski, J.; Schildhauer, T.J.; Biollaz, S.M.A. Production of synthetic natural gas (SNG) from coal and dry biomass—A technology review from 1950 to 2009. Fuel 2010, 89, 1763–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chu, B.; Zhai, X.; Jin, Y.; Cheng, Y. Total methanation of syngas to synthetic natural gas over Ni catalyst in a micro-channel reactor. Fuel 2012, 95, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassner, M.; Marechal, F. Thermo-economic optimization of the polygeneration of synthetic natural gas (SNG), power and heat from lignocellulosic biomass by gasification and methanation. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 5768–5789. [Google Scholar]

- Kienberger, T.; Zuber, C.; Novosel, K.; Baumhakl, C.; Karl, J. Desulfurization and in situ reduction within catalytic methanation of biogenous synthesis gas. Fuel 2013, 107, 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Gao, J.; Ping, Y.; Jia, L.; Gunawan, P.; Zhong, Z.; Xu, G.; Gu, F.; Su, F. Enhanced investigation of CO methanation over Ni/Al2O3 catalysts for synthetic natural gas production. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 4875–4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastas, P.T.; Kirchhoff, M.M.; Williamson, T.C. Catalysis as a foundational pillar of green chemistry. Appl. Catal. A 2001, 221, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, J.; Fechete, I.; Bresset, V.; Garin, F.; Tschamber, V. Effect of carbon black combustion on NOx trap catalyst performances. Catal. Today 2012, 189, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, F. New catalyst preparation technologies-observed from an industrial viewpoint. Appl. Catal. A 2001, 221, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertl, G. Heterogeneous catalysis on atomic scale. J. Mol. Catal. A 2002, 182–183, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djeddi, A.; Fechete, I.; Garin, F. Conversion of methylcyclopentane (MCP) on Pt/MoO2, Ir/MoO2 and Pt-Ir/MoO2 catalysts. Catal. Commun. 2012, 17, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, D.J. Hydrogen production by catalytic reforming of gaseous hydrocarbons (methane & LPG). Catal. Surv. Asia 2008, 12, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulaoued, A.; Fechete, I.; Donnio, B.; Bernard, M.; Turek, P.; Garin, F. Mo/KIT-6, Fe/KIT-6 and Mo-Fe/KIT-6 as new types of heterogeneous catalysts for the conversion of MCP. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012, 155, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haller, G.L. New catalytic concepts from new materials: Understanding catalysis from a fundamental perspective, past, present, and future. J. Catal. 2003, 216, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Especel, C.; Duprez, D.; Epron, F. Bimetallic catalysts for hydrogenation in liquid phase. C. R. Chim. 2014, 17, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascaso, S.; Gálvez, M.E.; da Costa, P.; Moliner, R.; Lázaro, M.J. On the influence of the alumina precursor in Fe-K/Al2O3 structured catalysts for the simultaneous removal of soot and NOx: From surface properties to reaction mechanism. C. R. Chim. 2014, 7–8, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzianowski, W.M. Negative carbon intensity of renewable energy technologies involving biomass or carbon dioxide as inputs. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 6507–6521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzianowski, W.M. Value-added carbon management technologies for low CO2 intensive carbon-based energy vectors. Energy 2012, 41, 280–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, P.; McFarland, E.W.; Metiu, H. CO2 methanation on Ru-doped ceria. J. Catal. 2011, 278, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, A.; Perez, P.J. Methane as raw material in synthetic chemistry: The final frontier. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 8809–8820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herranz, T.; Rojas, S.; Perez-Alonso, F.J.; Ojeda, M.; Terreros, P.; Fierro, J.L.G. Hydrogenation of carbon oxides over promoted Fe–Mn catalysts prepared by the microemulsion methodology. Appl. Catal. A 2006, 311, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janke, C.; Duyar, M.S.; Hoskins, M.; Farrauto, R. Catalytic and adsorption studies of the hydrogenation of CO2 to methane. Appl. Catal. B 2014, 152–153, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abello, S.; Berrueco, C.; Montane, D. High-loaded nickel–alumina catalyst for direct CO2 hydrogenation into synthetic natural gas (SNG). Fuel 2013, 113, 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holy, N.L.; Carey, T.F. Ethanol and n-propanol from syngas. Appl. Catal. 1985, 19, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shustorovich, E.; Bell, A.T. Analysis of CO hydrogenation pathways using the bond-order-conservation method. J. Catal. 1988, 113, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karelovic, A.; Ruiz, P. Mechanistic study of low temperature CO2 methanation over Rh/TiO2 catalysts. J. Catal. 2013, 301, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.P.; Abild-Pedersen, F.; Remediakis, I.N.; Bligaard, T.; Jones, G.; Engbæk, J.; Lytken, O.; Horch, S.; Nielsen, J.H.; Sehested, J.; et al. Structure sensitivity of the methanation reaction: H2-induced CO dissociation on nickel surfaces. J. Catal. 2008, 255, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoylu, A.E.; Önsan, Z.İ. Kinetics of CO Hydrogenation over Ni−Mo/Al2O3 catalysts with and without K promotion. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1998, 37, 2397–2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krylov, O.V.; Mamedov, A.K. Heterogeneous catalytic reactions of carbon dioxide. Russ. Chem. Rev. 1995, 64, 877–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, Z.; Stołecki, K.; Pilecka, G.W.R.; Miskiewicz, E.; Wilczkowska, E.; Karpinski, Z. Supported ruthenium catalysts for selective methanation of carbon oxides at very low COx/H2 ratios. Appl. Catal. A 2008, 342, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graca, I.; González, L.V.; Bacariza, M.C.; Fernandes, A.; Henriques, C.; Lopes, J.M.; Ribeiro, M.F. CO2 hydrogenation into CH4 on NiHNaUSY zeolites. Appl. Catal. B 2014, 147, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Hong, U.G.; Lee, J.; Baik, J.H.; Koh, D.J.; Lim, H.; Song, I.K. Methanation of carbon dioxide over mesoporous nickel–M–alumina (M = Fe, Zr, Ni, Y, and Mg) xerogel catalysts: Effect of second metal. Catal. Lett. 2012, 142, 860–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Babarao, R.; Hu, Z. Molecular simulations for energy, environmental and pharmaceutical applications of nanoporous materials: From zeolites, metal–organic frameworks to protein crystals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 3599–3612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fechete, I.; Caullet, P.; Dumitriu, E.; Hulea, V.; Kessler, H. Study of the conversion of aromatic hydrocarbons on EMT-type zeolite. Influence of the partial substitution of Al by Ga. Appl. Catal. A 2005, 280, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, A.; Schuth, F. Ordered mesoporous materials in catalysis. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2005, 77, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiano, D.P.; Hamad, B.; Cardoso, D.; Essayem, N. On the understanding of the remarkable activity of template-containing mesoporous molecular sieves in the transesterification of rapeseed oil with ethanol. J. Catal. 2010, 276, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothw, W.; Cejka, J. Two-dimensional zeolites: Dream or reality? J. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2011, 1, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fechete, I.; Debbih-Boustila, S.; Merkache, R.; Hulea, O.; Lazar, L.; Lutic, D.; Balasanian, I.; Garin, F. MnMCM-48, CoMCM-48 and CoMnMCM-48 mesoporous catalysts for the conversion of methylcyclopentane (MCP). Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2012, 11, 1931–1943. [Google Scholar]

- Garrone, E.; Fajula, F. Acidity and basicity of ordered silica-based mesoporous materials. Mol. Sieves 2008, 6, 213–267. [Google Scholar]

- Auroux, A. Acidity and Basicity determination by adsorption microcalorimetry. Mol. Sieves 2008, 6, 45–152. [Google Scholar]

- Lauron-Pernot, H. Evaluation of surface acido-basic properties of inorganic-based solids by model catalytic alcohol reaction networks. Catal. Rev. 2006, 48, 315–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fechete, I.; Simon-Masseron, A.; Dumitriu, E.; Lutic, D.; Caullet, P.; Kessler, H. The role of acidity of CeH–EMT–type zeolite for catalyzing toluene alkylation with methanol to xylenes. Rev. Roum. Chim. 2008, 53, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Cejka, J.; Centi, G.; Perez-Pariente, J.; Roth, W.J. Zeolite-based materials for novel catalytic applications: Opportunities, perspectives and open problems. Catal. Today 2012, 179, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinh-Thang, H.; Huang, Q.; Ungureanu, A.; Eić, M.; Trong-On, D.; Kaliaguine, S. Effect of the acid properties on the diffusion of C7 hydrocarbons in UL-ZSM-5 materials. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2006, 92, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fechete, I.; Gautron, E.; Dumitriu, E.; Lutic, D.; Caullet, P.; Kessler, H. Studies on the acidity and the stability of Fe3+ ions in the framework (Si,Fe)–MCM–22 zeolite. Selective para-xylene production by toluene disproportionation. Rev. Roum. Chim. 2008, 53, 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Valange, S.; Derouault, A.; Barrault, J.; Gabelica, Z. One-step generation of highly selective hydrogenation catalysts involving sub-nanometric Cu2O supported on mesoporous alumina: strategies to control their size and dispersion. J. Mol. Catal. A 2005, 228, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, M.; Yen, H.; Kleitz, F. Nanocast mesoporous mixed metal oxides for catalytic applications. C. R. Chim. 2014, 17, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trouvé, A.; Batonneau-Gener, I.; Valange, S.; Bonne, M.; Mignard, S. Tuning the hydrophobicity of mesoporous silica materials for the adsorption of organic pollutant in aqueous solution. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 201–202, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meloni, D.; Monaci, R.; Rombi, E.; Guimon, C.; Martinez, H.; Fechete, I.; Dumitriu, E. Synthesis and characterization of MCM-22 zeolite for the N2O oxidation of benzene to phenol. Stud. Surf. Sci. Catal. A 2002, 142, 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Serna, P.; Gates, B.C. Zeolite- and MgO-supported rhodium complexes and rhodium clusters: Tuning catalytic properties to control carbon–carbon vs. carbon–hydrogen bond formation reactions of ethene in the presence of H2. J. Catal. 2013, 308, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montes de Correa, C.; Castrillon, F.C. Supported bimetallic Pd-Co catalysts: Characterization and catalytic activity. J. Mol. Catal. A 2005, 228, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vedrine, J.C. Revisiting active sites in heterogeneous catalysis: Their structure and their dynamic behaviour. Appl. Catal. A 2014, 474, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensacia, N.; Fechete, I.; Moulay, S.; Hulea, O.; Boos, A.; Garin, F. Kinetic and equilibrium studies of lead (II) adsorption from aqueous media by KIT-6 mesoporous silica functionalized with—COOH. C. R. Chim. 2014, 17, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derouane, E.G.; Védrine, J.C.; Ramos Pinto, R.; Borges, P.M.; Costa, L.; Lemos, M.A.N.D.A.; Lemos, F.; Ribeiro, F.R. The acidity of zeolites: Concepts, measurements and relation to catalysis: A review on experimental and theoretical methods for the study of zeolite acidity. Catal. Rev. 2013, 55, 454–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verboekend, D.; Perez-Ramırez, J. Design of hierarchical zeolite catalysts by desilication. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2011, 1, 879–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensacia, N.; Fechete, I.; Moulay, S.; Boos, A.; Garin, F. Removal of cadmium (II) from aqueous media using COOH/TUD-1 mesoporous solid. Kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2014, 13, 2675–2686. [Google Scholar]

- Centi, G.; Genovese, C.; Giordano, G.; Katovic, A.; Perathoner, S. Performance of Fe-BEA catalysts for the selective hydroxylation of benzene with N2O. Catal. Today 2004, 91–92, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centi, G.; Perathoner, S. Opportunities and prospect in the chemical recycling of carbon dioxide to fuels. Catal. Today 2009, 148, 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Sun, T.; Peng, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, S. A comparison of Ni/SiC and Ni/Al2O3 catalyzed total methanation for production of synthetic natural gas. Appl. Catal. A 2013, 462–463, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zangeneh, F.T.; Sahebdelfar, S.; Ravanchi, M.T. Conversion of carbon dioxide to valuable petrochemicals: An approach to clean development mechanism. J. Nat. Gas Chem. 2011, 20, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behn, A. The synthesis of organic chemicals by catalytic reactions of carbon dioxide. Bull. Soc. Chim. Belg. 1985, 94, 671–683. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, S.; Yamazaki, Y. Organic and Bio-Organic Chemistry of Carbon Dioxide; Inoue, S., Yamazaki, Y., Eds.; Kodansha: Tokyo, Japan, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, J.; Sun, N.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, N.; Xiao, F.; Wei, W.; Sun, Y. A short review of catalysis for CO2 conversion. Catal. Today 2009, 148, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconer, J.L.; Zagli, A.E. Adsorption and methanation of carbon dioxide on a nickel/silica catalyst. J. Catal. 1980, 62, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherbee, G.D.; Bartholomew, C.H. Hydrogenation of CO2 on group VIII metals: II. Kinetics and mechanism of CO2 hydrogenation on nickel. J. Catal. 1982, 77, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peebles, D.E.; Goodman, D.W.; White, J.M. Methanation of carbon dioxide on nickel (100) and the effects of surface modifiers. J. Phys. Chem. 1983, 87, 4378–4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwood, M.; Doepper, R.; Renken, A. In-situ surface and gas phase analysis for kinetic studies under transient conditions. The catalytic hydrogenation of CO2. Appl. Catal. A 1997, 151, 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapidus, A.L.; Gaidai, N.A.; Nekrasov, N.V.; Tishkova, L.A.; Agafonov, Y.A.; Myshenkova, T.N. The mechanism of carbon dioxide hydrogenation on copper and nickel catalysts. Pet. Chem. 2007, 47, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, S.; Terunuma, H.; Kobayashi, H.; Takezawa, N. Methanation of carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide over nickel catalyst under the transient state. React. Kinet. Catal. Lett. 1987, 33, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schild, C.; Wokaun, A.; Baiker, A. On the mechanism of CO and CO2 hydrogenation reactions on zirconia-supported catalysts: A diffuse reflectance FTIR study: Part II. Surface species on copper/zirconia catalysts: Implications for methanoi synthesis selectivity. J. Mol. Catal. 1990, 63, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmett, P.H. Catalysis; Emmett, P.H., Ed.; Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1951; Volume 4, pp. 299–303. [Google Scholar]

- Oki, S.; Mezaki, R. Identification of rate-controlling steps for the water-gas shift reaction over an iron oxide catalyst. J. Phys. Chem. 1973, 77, 447–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oki, S.; Mezaki, R. Mechanistic structure of the water-gas shift reaction in the vicinity of chemical equilibrium. J. Phys. Chem. 1973, 77, 1601–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunde, P.J.; Kester, F.L. Rates of methane formation from carbon dioxide and hydrogen over a ruthenium catalyst. J. Catal. 1973, 30, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doehlemann, E. The mechanism of the water-gas reaction on an iron catalyst. Z. Elektrochem. 1938, 44, 178–183. [Google Scholar]

- Kulkova, N.V.; Temkin, M.I. Kinetics of the reaction of conversion of carbon monoxide by water vapor. Zh. Fiz. Khim. 1949, 23, 695–713. [Google Scholar]

- Kul’kova, N.V.; Kuznets, Z.D.; Temkin, M.I. The exchange of oxygen isotopes between carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide on an iron oxide catalyst. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 1953, 90, 1067–1070. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, C. Adsorbed Atomic Species as Intermediates in Heterogeneous Catalysisis; Eley, D.D., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1970; Volume 21, pp. 323–381. [Google Scholar]

- Jacquemin, M.; Beuls, A.; Ruiz, P. Catalytic production of methane from CO2 and H2 at low temperature: Insight on the reaction mechanism. Catal. Today 2010, 157, 462–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watwe, R.M.; Bengaard, H.S.; Rostrup-Nielsen, J.R.; Dumesic, J.A.; Norskov, J.K. Theoretical studies of stability and reactivity of CHx species on Ni(111). J. Catal. 2000, 189, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, M.; Robach, O.; Walker, C.; Quiros, C.; Isern, H.; Ferrer, S. Hydrogenation of carbon monoxide on Ni(III) investigated with surface X-ray diffraction at atmospheric pressure. Surf. Sci. 2004, 557, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, S.I.; Nakamura, M.; Doi, T.; Takezawa, N. Mechanisms of methanation of carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide over nickel/alumina catalysts. Appl. Catal. A 1993, 104, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, S.J.; Kang, H.J.; Kim, S.J.; Park, S.B.; Park, D.H.; Huh, D.S. Adsorbed carbon formation and carbon hydrogenation for CO2 methanation on the Ni(111) surface: ASED-MO study. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2005, 26, 1682–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solymosi, F.; Erdohelyi, A.; Bansagi, T. Methanation of CO2 on supported rhodium catalyst. J. Catal. 1981, 68, 371–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibraeva, Z.A.; Nekrasov, N.V.; Gudkov, B.S.; Yakerson, V.I.; Beisembaeva, Z.T.; Golosman, E.Z.; Kiperman, S.L. Kinetics of methanation of carbon dioxide on a nickel catalyst. Theor. Exp. Chem. 1990, 26, 620–624. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.Y.; Lee, H.M.; Park, J.N. Bifunctional mechanism of CO2 methanation on Pd-MgO/SiO2 catalyst: Independent roles of MgO and Pd on CO2 methanation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 7128–7131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehested, J.; Dahl, S.; Jacobsen, J.; Rostrup-Nielsen, J.R. Methanation of CO over nickel: mechanism and kinetics at high H2/CO ratios. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 2432–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fisher, I.A.; Bell, A.T. A Comparative study of CO and CO2 hydrogenation over Rh/SiO2. J. Catal. 1996, 162, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Leitenburg, C.; Trovarelli, A.; Kaspar, J. A temperature-programmed and transient kinetic study of CO2 activation and methanation over CeO2 supported noble metals. J. Catal. 1997, 166, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuls, A.; Swalus, C.; Jacquemin, M.; Heyen, G.; Karelovic, A.; Ruiz, P. Methanation of CO2: Further insight into the mechanism over Rh/γ-Al2O3 catalyst. Appl. Catal. B 2012, 113–114, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.N.; McFarland, E.W. A highly dispersed Pd–Mg/SiO2 catalyst active for methanation of CO2. J. Catal. 2009, 266, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Escribano, V.; Larrubia-Vargas, M.A.; Busca, G. On the mechanisms and the selectivity determining steps in syngas conversion over supported metal catalysts: An IR study. Appl. Catal. A 2007, 316, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovarelli, A.; de Leitenburg, C.; Dolcetti, G. CO and CO2 hydrogenation under transient conditions over Rh–CeO2: Novel positive effects of metal-support interaction on catalytic activity and selectivity. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1991, 472–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovarelli, A.; de Leitenburg, C.; Dolcetti, G.; Llorca, J. CO2 methanation under transient and steady-state conditions over Rh/CeO2 and CeO2-promoted Rh/SiO2: The role of surface and bulk ceria. J. Catal. 1995, 151, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tada, S.; Shimizu, T.; Kameyama, H.; Haneda, T.; Kikuchi, R. Ni/CeO2 catalysts with high CO2 methanation activity and high CH4 selectivity at low temperatures. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2012, 37, 5527–5531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.-A.; Choi, J.H.; Choi, K.M.; Lee, D.K.; Kang, J.K. Highly porous gallium oxide with a high CO2 affinity for the photocatalytic conversion of carbon dioxide into methane. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 5304–5307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabatier, P.; Senderens, J.B. New Synthesis of Methane. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris 1902, 134, 514–516. [Google Scholar]

- Inui, T.; Takeguchi, T. Effective conversion of carbon dioxide and hydrogen to hydrocarbons. Catal. Today 1991, 10, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Gong, J. Methanation of carbon dioxide: An Overview. Front. Chem. Eng. China 2011, 5, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, S.I.; Takezawa, N. Difference in the selectivity of CO and CO2. Methanation reactions. Chem. Eng. J. 1997, 68, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoylu, A.E.; Misirli, Z.; Onsan, I. Interaction between nickel and molybdenum in Ni–Mo/Al2O3 catalysts: I: CO2 methanation and SEM-TEM studies. Appl. Catal. A 1998, 168, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherbee, G.D.; Bartholomew, C.H. Hydrogenation of CO2 on group VIII metals: I. Specific activity of Ni/SiO2. J. Catal. 1981, 68, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, M.; Habazaki, H.; Asami, K.; Izumiya, K.; Hashimoto, K. Effect of tetragonal ZrO2 on the catalytic activity of Ni/ZrO2 catalyst prepared from amorphous Ni–Zr alloys. Catal. Commun. 2006, 7, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamasaki, M.; Komori, M.; Akiyama, E.; Habazaki, H.; Kawashima, A.; Asami, K.; Hashimoto, K. CO2 methanation catalysts prepared from amorphous Ni–Zr–Sm and Ni–Zr–misch metal alloy precursors. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1999, 267, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.W.; Kuo, M.S.; Tsay, M.T.; Hsieh, M.C. Hydrogenation of CO2 over nickel catalysts on rice husk ash-alumina prepared by incipient wetness impregnation. Appl. Catal. A 2003, 247, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.; Lim, S.; Yang, Y.; Wang, C.; Pfefferle, L.; Haller, G.L. Methanation of carbon dioxide on Ni-incorporated MCM-41 catalysts: The influence of catalyst pretreatment and study of steady-state reaction. J. Catal. 2007, 249, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, H.; Choi, J.-C.; Lee, S.-C.; Sakakura, T. Reactivity of diaryloxy palladium complex with TMEDA (N,N,N',N'-Tetramethylethylenediamine) ligand toward carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide. Organometallics 2002, 21, 1216–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vol’pin, M.E.; Kolomnikov, I.S. Reactions of carbon dioxide with transition metal compounds. Pure Appl. Chem. 1973, 33, 567–582. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.; Harper, A.S.; DeSimone, J.M.; Murray, R.W. Ion atmosphere relaxation control of electron transfer dynamics in a plasticized carbon dioxide redox polyether melt. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 1096–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergquist, C.; Fillebeen, T.; Morlok, M.M.; Parkin, G. Protonation and reactivity towards carbon dioxide of the mononuclear tetrahedral zinc and cobalt hydroxide complexes, [TpBut,Me]ZnOH and [TpBut,Me]CoOH: Comparison of the reactivity of the metal hydroxide function in synthetic analogues of carbonic anhydrase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 6189–6199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.; Wu, T.; Xie, H.M.; Zheng, X.X. Effects of structure on the carbon dioxide methanation performance of Co-based catalysts. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2013, 38, 10012–10018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-C.; Sakakura, T. Roles played in the photocatalytic activation of hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 7762–7763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlenburg, L.; Prengel, C. Alkyl and aryl compounds of iridium and rhodium. 18. Oligophosphine ligands. 6. Reactivity of some alkyls and aryls of rhodium and iridium toward carbon dioxide. Facile formation and x-ray structural characterization of the peroxocarbonato complex [cyclic]—mer—Rh (4-MeC6H4) [OOC(O)O][PhP(CH2CH2CH2PPh2)2]. Organometallics 1984, 3, 934–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetrick, S.M.; Xu, C.; Pinkes, J.R.; Cutler, A.R. Synthesis of M2Rh2 Bis (μ3-carbon dioxide) complexes from the reaction between [Rh(OH)(η4-COD)]2 and cationic metal carbonyls. Organometallics 1998, 17, 1861–1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zakharov, L.N.; Rheingold, A.L.; Kemp, R.A. Insertion of carbon dioxide into Mg-N bonds. Structural characterization of a previously unknown η2 chelation mode to magnesium in magnesium carbamates. Organometallics 2004, 23, 4788–4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loferer, M.J.; Tautermann, C.S.; Loeffler, H.H.; Liedl, K.R. Influence of backbone conformations of human carbonic anhydrase II on carbon dioxide hydration: Hydration pathways and binding of bicarbonate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 8921–8927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasuda, H.; Okamoto, T.; Matsuoka, Y.; Nakamura, A.; Kai, Y.; Kanehisa, N.; Kasai, N. Diverse reaction courses in the controlled carbometalation of heterocumulenes with zirconium-diene complexes and molecular structures of carbon dioxide, isocyanate and ketene 1:1 and 1:2 inserted compounds. Organometallics 1989, 8, 1139–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkes, J.R.; Steffey, B.D.; Vites, J.C.; Cutler, A.R. Carbon dioxide insertion into the iron-zirconium and ruthenium-zirconium bonds of the heterobimetallic complexes Cp(CO)2MZr(Cl)Cp2: Direct production of the .mu.-.eta.1(C): Eta.2(O,O')-CO2 compounds Cp(CO)2MCO2Zr(Cl)Cp2. Organometallics 1994, 13, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingler, R.J.; Bloom, I.; Rathke, J.W. Thermodynamics for the addition of a tin hydride to carbon dioxide. Organometallics 1985, 4, 1893–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lescop, C.; Arliguie, T.; Lance, M.; Nierlich, M.; Ephritikhine, M. Bis pentamethyl cyclopentadienyl uranium (IV) thiolate compounds. Synthesis and reactions with CO2 and CS2. J. Organomet. Chem. 1999, 580, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, R.E., Jr.; Antonelli, D.M.; Henling, L.M.; Schaefer, W.P.; Hardcastle, K.I.; Bercaw, J.E. A cationic imido complex of permethyltantalocene: H2 and carbon-hydrogen bond activation, [2+2] cycloaddition reactions, and an unusual reaction with carbon dioxide that affords coordinated isocyanate. Organometallics 1998, 17, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antinolo, A.; Carrillo-Hermosilla, F.; del Hierro, I.; Otero, A.; Fajardo, M.; Mugnier, Y. Synthesis and characterization of new alkyl-carbon dioxide compounds and the first neutral acyl-carbonyl niobocene complexes. Organometallics 1997, 16, 4161–4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souter, P.F.; Andrews, L. A spectroscopic and theoretical study of the reactions of group 6 metal atoms with carbon dioxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 7350–7360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetcuti, P.A.; Knobler, C.B.; Hawthorne, M.F. Intramolecular conversion of a five-membered iridacycle to a three-membered counterpart by carbon dioxide extrusion. Organometallics 1986, 5, 1913–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivanco, M.; Ruiz, J.; Floriani, C.; Chiesi-Villa, A.; Guastini, C. Stepwise insertion of isocyanides and carbon dioxide into vanadium-aryl bonds: Chemistry of a tris (eta.2-iminoacyl) vanadium(III) complex. Organometallics 1990, 9, 2185–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuda, T.; Ueda, K.; Saegusa, T. Carbon dioxide insertion into organocopper and organosilver compounds. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Comm. 1974, 380–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivanco, M.; Ruiz, J.; Floriani, C.; Chiesi-Villa, A.; Rizzoli, C. Chemistry of the vanadium-carbon sigma. bond. 1. Insertion of carbon monoxide, isocyanides, carbon dioxide, and heterocumulenes into the V-C bond of tris(mesityl)vanadium(III). Organometallics 1993, 12, 1794–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindo, A.; Pastor, A.; Perez, P.J.; Carmona, E. Bis (ethylene) complexes of molybdenum and tungsten and their reactivity toward carbon dioxide. New examples of acrylate formation by coupling of ethylene and carbon dioxide. Organometallics 1993, 12, 4443–4451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darensbourg, D.J.; Kudaroski, R.; Delord, T. Synthesis and X-ray structure of anionic chelating phosphine-acyl derivative of tungsten, [cyclic] [PPh4][W(CO)4C(O)CH2CH2CH2PPh2], and the reactivity of its decarbonylated analog with carbon dioxide. Organometallics 1985, 4, 1094–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birdwhistell, K.R.; Templeton, J.L. Reactions at the β-carbon of anionic tungsten acetylide complexes: Ion pairing, vinylidene formation, and carbon dioxide binding. Organometallics 1985, 4, 2062–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, E.; Munoz, M.A.; Perez, P.J.; Poveda, M.L. Rotational isomerism in bis (carbon dioxide) complexes of molybdenum generated by conrotatory motion of the CO2 ligands. Organometallics 1990, 9, 1337–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, R.; Carmona, E.; Galindo, A.; Gutierrez, E.; Marın, J.M.; Monge, A.; Poveda, M.L.; Ruiz, C.; Savariault, J.M. Formation of carboxylate complexes from the reactions of carbon dioxide with ethylene complexes of molybdenum and tungsten. X-ray and neutron diffraction studies. Organometallics 1989, 8, 2430–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, L.K.; Fox, J.R.; Cooper, N.J. Reactions of carbon dioxide with the electron-rich polyhydride complex [Mo(dmpe)2H4]. Organometallics 1987, 6, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.K.; Ho, D.M.; Orchin, M. Reaction of electrophiles with manganese(I) and rhenium(I) alkoxide complexes: Reversible absorption of atmospheric carbon dioxide. Organometallics 1993, 12, 1714–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darensbourg, D.J.; Lee, W.-Z.; Phelps, A.L.; Guidry, E. Kinetic study of the insertion and deinsertion of carbon dioxide into fac-(CO)3(dppe)MnOR derivatives. Organometallics 2003, 22, 5585–5588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, R.F.; Cooper, J.C. The first example of photochemically activated carbon dioxide insertion into transition-metal-carbon bonds. Organometallics 1987, 6, 2448–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchbauer, F.G.; Pellny, P.-M.; Sun, H.; Burlakov, V.V.; Arndt, P.; Baumann, W.; Spannenberg, A.; Rosenthal, U. Synthesis and reactions with carbon dioxide of mono (σ-alkynyl) Titanocene (III) Complexes Cp*2Ti(C⋮CR) (R = Me, t-Bu) and the Corresponding “Ate” Complexes [Cp*2Ti(C⋮CR)2Li(THF)n] (R = SiMe3, t-Bu, Ph). Organometallics 2001, 20, 5289–5296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuseppetti, M.E.; Cutler, A.R. Metallocarboxylate trialkylsilyl esters: A means of derivatizing the carbon dioxide-containing [.eta.1-C] metallocarboxylates Cp(CO)2FeCO2-Li+ and Cp(CO)2FeCO2-Na+. Organometallics 1987, 6, 970–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, M.; Akita, M.; Tani, K.; Kumagai, K.; Kasuga, N.C.; Fukuoka, A.; Komiya, S. Activation of coordinated carbon dioxide in Fe(CO2)(depe)2 by group 14 electrophiles. Organometallics 1997, 16, 4206–4213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, P.H.; Jun, K.-W.; Lee, S.-J.; Choi, M.-J.; Lee, K.-W. Hydrogenation of carbon dioxide over alumina supported Fe-K catalysts. Catal. Lett. 1996, 40, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satthawong, R.; Koizumi, N.; Song, C.; Prasassarakich, P. Comparative study on CO2 hydrogenation to higher hydrocarbons over Fe-Based bimetallic catalysts. Top. Catal. 2014, 57, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.-W.; Hsiao, T.-J.; Shih, J.-D. Hydrogenation of CO2 over a rice husk ash supported nickel catalyst prepared by deposition-precipitation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1998, 37, 3838–3845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagli, E.; Falconer, J. Carbon dioxide adsorption and methanation on ruthenium. J. Catal. 1981, 69, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulou, P.; Kondarides, D.I.; Verykios, X.E. Selective methanation of CO over supported noble metal catalysts: Effects of the nature of the metallic phase on catalytic performance. Appl. Catal. A 2008, 344, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherbee, G.D.; Bartholomew, C.H. Hydrogenation of CO2 on group VIII metals: IV. Specific activities and selectivities of silica-supported Co, Fe, and Ru. J. Catal. 1984, 87, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sane, S.; Bonnier, J.M.; Damon, J.P.; Masson, J. Raney metal catalysts: I. comparative properties of raney nickel proceeding from Ni-Ai intermetallic phases. Appl. Catal. 1984, 9, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.D.; Moon, M.J.; Park, J.H.; Park, S.S.; Hong, S.S. Raney Ni catalysts derived from different alloy precursors Part II. CO and CO2 methanation activity. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2005, 22, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaccato, K.; Carhart, R.; Hagemeyer, A.; Lesik, A.; Strasser, P.; Volpe, A.F., Jr.; Turner, H.; Weinberg, H.; Grasselli, R.K.; Brooks, C. Competitive CO and CO2 methanation over supported noble metal catalysts in high throughput scanning mass spectrometer. Appl. Catal. A 2005, 296, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Wang, L.; Xu, Y.; Sun, Y. Selective methanation of carbon monoxide over Ru-based catalysts in H2-rich gases. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2012, 18, 1590–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erekson, E.J.; Sughrue, E.L.; Bartholomew, C.H. Catalyst degradation in high temperature methanation. Fuel Process. Technol. 1981, 5, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnelli, M.; Kolb, M.; Nicot, C.; Mirodatos, C. Sintering of a Ni-based catalyst during CO hydrogenation: Kinetics and modeling. Stud. Surf. Sci. Catal. 1991, 68, 605–612. [Google Scholar]

- Agnelli, M.; Kolb, M.; Mirodatos, C. CO hydrogenation on a nickel catalyst. I. Kinetics and modeling of a low temperature sintering process. J. Catal. 1994, 148, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Yang, X.; Gao, G.; Wang, K.; Shi, Q.; Wang, J.; Han, C.; Liu, J.; Tong, M.; Liang, X.; Li, C. Mesoporous zirconia-modified clays supported nickel catalysts for CO and CO2 methanation. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2014, 39, 18894–18907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodama, T.; Kitayama, Y.; Tsuji, M.; Tamaura, Y. Methanation of CO2 using ultrafine NixFe3–xO4. Energy 1997, 22, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, H.; Fujiwara, M.; Matsumura, Y.; Miyamura, H.; Souma, Y. Methanation of carbon dioxide over LaNi4X type catalysts. Energy Convers. Mgmt. 1995, 36, 653–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- </b>Perkas, N.; Amirian, G.; Zhong, Z.; Teo, J.; Gofer, Y.; Gedanken, A. Methanation of carbon dioxide on Ni catalysts on mesoporous ZrO2 doped with rare earth oxides. Catal. Lett. 2009, 130, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, K.O.; Streekala, R.; Rashid, K.K.A.; Yusuff, K.K.M.; Sen, B. Doping effects of cerium oxide on Ni/Al2O3 catalysts for methanation. Catal. Today 1999, 49, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rynkowski, J.M.; Paryjczak, T.; Lewicki, A.; Szynkowska, M.I.; Maniecki, T.P.; Józwiak, W.K. Characterization of Ru/CeO2–Al2O3 catalysts and their performance in CO2 methanation. React. Kinet. Catal. Lett. 2000, 71, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laosiripojana, N.; Assabumrungrat, S. Methane steam reforming over Ni/Ce–ZrO2 catalyst: Influences of Ce–ZrO2 support on reactivity, resistance toward carbon formation, and intrinsic reaction kinetics. Appl. Catal. A 2005, 290, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monte, R.; Fornasiero, P.; Kaspar, J.; Rumori, P.; Gubitosa, G.; Graziani, M. Pd/Ce0.6Zr0.4O2/Al2O3 as advanced materials for three-way catalysts: Part 1. Catalyst characterisation, thermal stability and catalytic activity in the reduction of NO by CO. Appl. Catal. B 2000, 24, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouarnadasse, S.; Pajonk, G.M.; Germain, J.E.; Teichner, S.J. Catalytic nitroxidation of toluene into benzonitrile over nickel oxide-alumina xero- or aero-gel catalysts. Appl. Catal. 1984, 9, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, C.K.; Bartholomew, C.H. Hydrogenation of carbon dioxide on group VIII metals: III, Effects of support on activity/selectivity and adsorption properties of nickel. Appl. Catal. 1983, 7, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.A.A.; Jalil, A.A.; Triwahyono, S.; Mukti, R.R.; Taufiq-Yap, Y.H.; Sazegar, M.R. Highly active Ni-promoted mesostructured silica nanoparticles for CO2 methanation. Appl. Catal. B 2014, 147, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-S.; Lin, J.-H.; Wua, J.-H.; Chiang, C.-Y. Growth of carbon nanofibers synthesized from CO2 hydrogenation on a K/Ni/Al2O3 catalyst. Catal. Commun. 2009, 11, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.; Hong, U.G.; Lee, J.; Seo, J.G.; Baik, J.H.; Koh, D.J.; Lim, H.; Song, I.K. Methanation of carbon dioxide over mesoporous Ni–Fe–Al2O3 catalysts prepared by a coprecipitation method: Effect of precipitation agent. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2013, 19, 2016–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliot, D.J.; Lunsford, J.H. Kinetics of the Methanation Reaction over Ru, Ru–Ni, Ru–Cu, and Ni Clusters in Zeolite-Y. J. Catal. 1979, 57, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, N.C.; Wolf, E.E. CO methanation activity and XPS studies of Pd supported on ZSM-5 and Y-zeolites. Appl. Catal. 1984, 13, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckle, S.; Denkwitz, Y.; Behm, R.J. Activity, selectivity, and adsorbed reaction intermediates/reaction side products in the selective methanation of CO in reformate gases on supported Ru catalysts. J. Catal. 2010, 269, 255–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagnoli, M.V.; Gallegos, N.G.; Alvarez, A.M.; Bengoa, J.F.; Yeramián, A.A.; Schmal, M.; Marchetti, S.G. Catalytic CO hydrogenation on potassic Fe/zeolite LTL. Appl. Catal. A 2002, 230, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Mageed, A.M.; Eckle, S.; Anfang, H.G.; Behm, R.J. Selective CO methanation in CO2-rich H2 atmospheres over a Ru/zeolite catalyst: The influence of catalyst calcination. J. Catal. 2013, 298, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunemann, V.; Trevino, H.; Lei, G.D.; Tomczack, D.C.; Sachmer, W.M.H.; Fogash, K.; Dumesic, J.A. Fe promoted Rh-clusters in Zeolite NaY: Characterization and catalytic performance in CO hydrogenation. J. Catal. 1995, 153, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scirè, S.; Crisafulli, C.; Maggiore, R.; Minicò, S.; Galvagno, S. Influence of the support on CO2 methanation over Ru catalysts: An FT-IR study. Catal. Lett. 1998, 51, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patzelová, V.; Zukal, A.; Tvarukova, Z.; Malícek, O. Hydrogenation of CO and CO2 over stabilized NiY catalysts. Stud. Surf. Sci. Catal. 1984, 18, 367–374. [Google Scholar]

- Eckle, S.; Anfang, H.-G.; Behm, R.J. Reaction intermediates and side products in the methanation of CO and CO2 over supported Ru catalysts in H2-rich reformate gases. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jwa, E.; Lee, S.B.; Lee, H.W.; Mok, Y.S. Plasma-assisted catalytic methanation of CO and CO2 over Ni–zeolite catalysts. Fuel Proc. Technol. 2013, 108, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krämer, M.; Stöwe, K.; Duisberg, M.; Müller, F.; Reiser, M.; Sticher, S.; Maier, W.F. The impact of dopants on the activity and selectivity of a Ni-based methanation catalyst. Appl. Catal. A 2009, 369, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, Y.; Kolb, G.; Zapf, R.; Hessel, V.; Lowe, H. Selective methanation of carbon oxides in a microchannel reactor-primary screening and impact of gas additives. Catal. Today 2007, 125, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeue, K.; Yamashita, H.; Anpo, M.; Takewaki, T. Photocatalytic reduction of CO2 with H2O on Ti-β zeolite photocatalysts: Effect of the hydrophobic and hydrophilic properties. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 8350–8355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, T.; Fujishima, A.; Konishi, S.; Honda, K. Photoelectrocatalytic reduction of carbon dioxide in aqueous suspensions of semiconductor powders. Nature 1979, 277, 637–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centi, G.; Perathoner, S. Towards solar fuels from water and CO2. ChemSusChem 2010, 3, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhakshinamoorthy, A.; Navalon, S.; Corma, A.; Garcia, H. Photocatalytic CO2 reduction by TiO2 and related titanium containing solids. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 9217–9233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Yamashita, H.; Anpo, M. Photocatalytic reduction of CO2 with H2O on various titanium oxide photocatalysts. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 3165–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navalón, S.; Dhakshinamoorthy, A.; Álvaro, M.; Garcia, H. Photocatalytic CO2 reduction using non-titanium metal oxides and sulfides. ChemSusChem 2013, 6, 562–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dvoranova, D.; Brezova, V.; Mazur, M.; Malati, M.A. Investigations of metal-doped titanium dioxide photocatalysts. Appl. Catal. B 2002, 37, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, J.M. Heterogeneous photocatalysis: Fundamentals and applications to the removal of various types of aqueous pollutants. Catal. Today 1999, 53, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litter, M.I.; Navio, J.A. Photocatalytic properties of iron-doped titania semiconductors photocatalytic properties of iron-doped titania semiconductors. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 1996, 98, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burda, C.; Lou, Y.B.; Chen, X.B.; Samia, A.C.S.; Stout, J.; Gole, J.L. Enhanced nitrogen doping in TiO2 nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2003, 3, 1049–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.C.; Ho, W.K.; Yu, J.G.; Yip, H.; Wong, P.K.; Zhao, J.C. Efficient visible-light-induced photocatalytic disinfection on sulfur-doped nanocrystalline titania. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 1175–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, C.G.; Juarez, R.; Marino, T.; Molinari, R.; Garcia, H. Influence of excitation wavelength (UV or visible light) on the photocatalytic activity of titania containing gold nanoparticles for the generation of hydrogen or oxygen from water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Primo, A.; Corma, A.; Garcia, H. Titania supported gold nanoparticles as photocatalyst. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 886–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mul, G.; Schacht, C.; van Swaaij, W.P.M.; Moulijn, J.A. Functioning devices for solar to fuel conversion. Chem. Eng. Process 2012, 51, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corma, A.; Garcia, H. Photocatalytic reduction of CO2 for fuel production: Possibilities and challenges. J. Catal. 2013, 308, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izumi, Y. Recent advances in the photocatalytic conversion of carbon dioxide to fuels with water and/or hydrogen using solar energy and beyond. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013, 257, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitano, M.; Matsuoka, M.; Ueshima, M.; Anpo, M. Recent developments in titanium oxide-based photocatalysts. Appl. Catal. A 2007, 325, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, M.; Anpo, M.J. Local structures excited states and photocatalytic reactivities of highly dispersed catalysts constructed within zeolites. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 2003, 3, 225–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usubharatana, P.; McMartin, D.; Veawab, A.; Tontiwachwuthikul, P. Photocatalytic process for CO2 emission reduction from industrial flue gas streams. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2006, 45, 2558–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Han, H.; Frei, H. CO2 splitting by H2O to CO and O2 under UV light in TiMCM-41 silicate sieve. J. Phys. Chem. B 2004, 108, 18269–18273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, I.-H.; Wu, J.C.S.; Chou, H.-Y. Effects of sol-gel procedures on the photocatalysis of Cu/TiO2 in CO2 photoreduction. J. Catal. 2004, 221, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shioya, Y.; Ikeue, K.; Ogawa, M.; Anpo, M. Synthesis of transparent Ti-containing mesoporous silica thin film materials and their unique photocatalytic activity for the reduction of CO2 with H2O. Appl. Catal. A 2003, 254, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, H.; Koike, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Ishizuka, M.; Tanaka, J.; Takeuchi, K.; Sasaki, Y. High-pressure photocatalytic reduction of carbon dioxide using [fac-Re(bpy)(CO)3P(OiPr)3]+ (bpy = 2,2'-bipyridine). J. Mol. Catal. A 2002, 179, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeue, K.; Nozaki, S.; Ogawa, M.; Anpo, M. Photocatalytic Reduction of CO2 with H2O on Ti-containing porous silica thin film photocatalysts. Catal. Lett. 2002, 80, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeue, K.; Nozaki, S.; Ogawa, M.; Anpo, M. Characterization of self-standing Ti-containing porous silica thin films and their reactivity for the photocatalytic reduction of CO2 with H2O. Catal. Today 2002, 74, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, H.; Ikeue, K.; Takewaki, T.; Anpo, M. In situ XAFS studies on the effects of the hydrophobic–hydrophilic properties of Ti-β zeolites in the photocatalytic reduction of CO2 with H2O. Top. Catal. 2002, 18, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saladin, F.; Forss, L.; Kamber, I. Photosynthesis of CH4 at a TiO2 surface from gaseous H2O and CO2. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1995, 533–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anpo, M.; Chiba, K. Photocatalytic reduction of CO2 on anchored titanium oxide catalysts. J. Mol. Catal. 1992, 74, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anpo, M.; Yamashita, H.; Ichihashi, Y.; Fujii, Y.; Honda, M. Photocatalytic reduction of CO2 with H2O on titanium oxides anchored within micropores of zeolites: Effects of the structure of the active sites and the addition of Pt. J. Phys. Chem. B 1997, 101, 2632–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, H.; Fujii, Y.; Ichihashi, Y.; Zhang, S.G.; Ikeue, K.; Park, D.R.; Koyano, K.; Tatsumi, T.; Anpo, M. Selective formation of CH3OH in the photocatalytic reduction of CO2 with H2O on titanium oxides highly dispersed within zeolites and mesoporous molecular sieves. Catal. Today 1998, 45, 221–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anpo, M.; Yamashita, H.; Ikeue, K.; Fujii, Y.; Zhang, S.G.; Ichihashi, Y.; Park, D.R.; Suzuki, Y.; Koyano, K.; Tatsumi, T. Photocatalytic reduction of CO2 with H2O on Ti–MCM–41 and Ti–MCM–48 mesoporous zeolite catalysts. Catal. Today 1998, 44, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeue, K.; Yamashita, H.; Anpo, M. Photocatalytic reduction of CO2 with H2O on titanium oxide prepared within the FSM-16 mesoporous zeolites. Chem. Lett. 1999, 11, 1135–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.S.; Chang, J.S.; Park, S.E.; Ikeue, K.; Anpo, M. Photoreduction of carbondioxide on surface functionalized nanoporous catalysts. Top. Catal. 2005, 35, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fechete, I.; Vedrine, J.C. Nanoporous Materials as New Engineered Catalysts for the Synthesis of Green Fuels. Molecules 2015, 20, 5638-5666. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules20045638

Fechete I, Vedrine JC. Nanoporous Materials as New Engineered Catalysts for the Synthesis of Green Fuels. Molecules. 2015; 20(4):5638-5666. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules20045638

Chicago/Turabian StyleFechete, Ioana, and Jacques C. Vedrine. 2015. "Nanoporous Materials as New Engineered Catalysts for the Synthesis of Green Fuels" Molecules 20, no. 4: 5638-5666. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules20045638