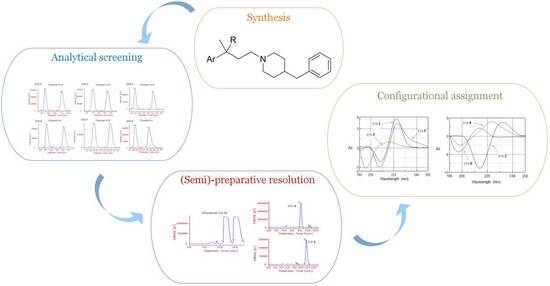

Novel Enantiopure Sigma Receptor Modulators: Quick (Semi-)Preparative Chiral Resolution via HPLC and Absolute Configuration Assignment

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis

2.2. Analytical Screening and Development of a Scalable Resolution Method

2.3. Preparation of Enantiomeric 1–6 through HPLC

2.4. Absolute Configurational Assignment

3. Experimental Section

3.1. HPLC-UV Chiral Resolution

3.2. Electronic Circular Dichroism

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of Open Access Journals |

| DEA | Diethylamine |

| ECD | Electronic circular dichroism |

| EtOH | Ethanol |

| IPA | Isopropanol |

| MeOH | Methanol |

| n-hep | n-Heptane |

| TFA | Trifluoroacetic acid |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

References

- Aydar, E.; Palmer, C.P.; Djamgoz, M.B. Sigma receptors and cancer: Possible involvement of ion channels. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 5029–5035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collina, S.; Gaggeri, R.; Marra, A.; Bassi, A.; Negrinotti, S.; Negri, F.; Rossi, D. Sigma receptor modulators: A patent review. Exp. Opin. Ther. Pat. 2013, 23, 597–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.S.; Lu, H.L.; Zhang, L.J.; Wu, Z. Sigma-2 receptor ligands and their perspectives in cancer diagnosis and therapy. Med. Res. Rev. 2014, 34, 532–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Rouzier, R.; Albarracin, C.T.; Sahin, A.; Wagner, P.; Yang, Y.; Smith, T.L.; Meric Bernstam, F.; Marcelo, A.C.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; Pusztai, L. Expression of sigma 1 receptor in human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2004, 87, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aydar, E.; Onganer, P.; Perrett, R.; Djamgoz, M.B.; Palmer, C.P. The expression and functional characterization of sigma (sigma) 1 receptors in breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Lett. 2006, 242, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crottes, D.; Guizouarn, H.; Martin, P.; Borgese, F.; Soriani, O. The sigma-1 receptor: A regulator of cancer cell electrical plasticity? Front. Physiol. 2013, 4, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Megalizzi, V.; le Mercier, M.; Decaestecker, C. Sigma receptors and their ligands in cancer biology: Overview and new perspectives for cancer therapy. Med. Res. Rev. 2012, 32, 410–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collina, S.; Loddo, G.; Urbano, M.; Linati, L.; Callegari, A.; Ortuso, F.; Alcaro, S.; Laggner, C.; Langer, T.; Prezzavento, O.; et al. Design, synthesis, and SAR analysis of novel selective sigma1 ligands. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007, 15, 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, D.; Urbano, M.; Pedrali, A.; Serra, M.; Zampieri, D.; Mamolo, M.G.; Laggner, C.; Zanette, C.; Florio, C.; Shepmann, D.; et al. Design, synthesis and SAR analysis of novel selective sigma1 ligands (Part 2). Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010, 18, 1204–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, D.; Pedrali, A.; Urbano, M.; Gaggeri, R.; Serra, M.; Fernandez, L.; Fernandez, M.; Caballero, J.; Rosinsvalle, S.; Prezzavento, O.; et al. Identification of a potent and selective σ1 receptor agonist potentiating NGF-induced neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011, 19, 6210–6224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, D.; Marra, A.; Picconi, P.; Serra, M.; Catenacci, L.; Sorrenti, M.; Laurini, E.; Fermeglia, M.; Pricl, S.; Brambilla, S.; et al. Identification of RC-33 as a potent and selective σ1 receptor agonist potentiating NGF-induced neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. Part 2: G-scale synthesis, physicochemical characterization and in vitro metabolic stability. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 2577–2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, D.; Pedrali, A.; Gaggeri, R.; Marra, A.; Pignataro, L.; Laurini, E.; DalCol, V.; Fermeglia, M.; Pricl, S.; Schepmann, D.; et al. Chemical, pharmacological, and in vitro metabolic stability studies on enantiomerically pure RC-33 compounds: promising neuroprotective agents acting as σ1 receptor agonists. Chem. Med. Chem. 2013, 8, 1514–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, D.; Pedrali, A.; Marra, A.; Pignataro, L.; Schepmann, D.; Wünsch, B.; Ye, L.; Leuner, K.; Peviani, M.; Curti, D.; Azzolina, O.; Collina, S. Studies on the Enantiomers of as Neuroprotective Agents: Isolation, Configurational Assignment, and Preliminary Biological Profile. Chirality 2013, 25, 814–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, D.; Marra, A.; Rui, M.; Laurini, E.; Fermeglia, M.; Pricl, S.; Schepmann, D.; Wuensch, B.; Peviani, M.; Curti, D.; et al. A step forward in the sigma enigma: A role for chirality in the sigma1 receptor-ligand interaction? MedChemComm 2014, 6, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.M.; Bowen, W.D.; Walker, F.O.; Matsumoto, R.R.; De Costa, B.; Rice, K.C. Sigma receptors: Biology and function. Pharmacol. Rev. 1990, 42, 355–402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Collina, S.; Loddo, G.; Urbano, M.; Rossi, D.; Mamolo, M.G.; Zampieri, D.; Alcaro, S.; Gallelli, A.; Azzolina, O. Enantioselective chromatography and absolute configuration of N,N-dimethyl-3-(naphthalen-2-yl)-butan-1-amines: Potential Sigma1 ligands. Chirality. 2006, 18, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, D.; Nasti, R.; Marra, A.; Meneghini, S.; Mazzeo, G.; Longhi, G.; Memo, M.; Cosimelli, B.; Greco, G.; Novellino, E.; et al. Enantiomeric 4-Acylamino-6-alkyloxy-2 Alkylthiopyrimidines As Potential A3 Adenosine Receptor Antagonists: HPLC Chiral Resolution and Absolute Configuration Assignment by a Full Set of Chiroptical Spectroscopy. Chirality 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaggeri, R.; Rossi, D.; Collina, S.; Mannucci, B.; Baierl, M.; Juza, M. Quick development of an analytical enantioselective high performance liquid chromatography separation and preparative scale-up for the flavonoid Naringenin. J. Chromatogr. A 2011, 1218, 5414–5422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, D.; Marra, A.; Rui, M.; Brambilla, S.; Juza, M.; Collina, S. “Fit-for-purpose” development of analytical and (semi)preparative enantioselective high performance liquid and supercritical fluid chromatography for the access to a novel σ1 receptor agonist. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2016, 118, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pace, V.; Martínez, F.; Fernández, M.; Sinisterra, J.V.; Alcántara, A.R. Highly Efficient Synthesis of New α-Arylamino-α′-chloropropan-2-ones via Oxidative Hydrolysis of Vinyl Chlorides Promoted by Calcium Hypochlorite. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2009, 351, 3199–3206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sample Availability: Samples of all compounds are available from the authors.

| Compound | λmin | Δεmin | λmax | Δεmax |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (S)-RC-34 | 206.5 | −2.78 | 253.0 | 1.09 |

| (+)-1 | 208.5 | −3.58 | 222.5 | 7.59 |

| (+)-3 | 195.5 | −5.19 | 216.5 | 1.57 |

| (+)-5 | 207.5 | −4.82 | 223.5 | 6.31 |

| Compound | λmin | Δεmin | λmax | Δεmax |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (S)-RC-33 | 229.8 | −0.61 | 255.0 | 0.47 |

| (+)-2 | 214.0 | −9.04 | 232.5 | 3.56 |

| (+)-4 | 198.5 | −2.26 | 223.0 | 3.85 |

| (+)-6 | 198.0 | −4.34 | 214.0 | 2.18 |

| Compound | Ar | R |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |  | OH |

| 2 | H | |

| 3 |  | OH |

| 4 | H | |

| 5 |  | OH |

| 6 | H |

| Entry | Mobile Phase Composition (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MeOH | EtOH | n-hep | IPA | |

| 1 | 100 | - | - | - |

| 2 | 50 | 50 | - | - |

| 3 | - | 10 | 90 | - |

| 4 | - | - | 90 | 10 |

| Compound | Mobile Phase | K1 | K2 | Α | Rs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-hep (%) | EtOH (%) | IPA (%) | |||||

| (R/S)-1 | 90 | 10 | - | 1.52 | 1 | - | |

| 90 | - | 10 | 4.45 | 1 | - | ||

| 92 | - | 8 | 7.76 | 8.72 | 1.12 | 1.44 | |

| (R/S)-2 | 90 | 10 | - | 1.93 | 1 | - | |

| 90 | - | 10 | 7.83 | 9.62 | 1.23 | 2.36 | |

| (R/S)-3 | 90 | 10 | - | 1.29 | 1 | - | |

| 90 | - | 10 | 1.35 | 1 | - | ||

| (R/S)-4 | 90 | 10 | - | 1.56 | 1 | - | |

| 90 | - | 10 | 6.52 | 8.68 | 1.33 | 3.08 | |

| (R/S)-5 | 90 | 10 | - | 3.24 | 1 | - | |

| 90 | - | 10 | 15.79 | 1 | - | ||

| (R/S)-6 | 90 | 10 | - | 4.07 | 1 | - | |

| 90 | - | 10 | 27.14 | 29.97 | 1.11 | 1.26 | |

| Compound | Mobile Phase | K1 | K2 | α | Rs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-hep (%) | MeOH (%) | EtOH (%) | IPA (%) | |||||

| (R/S)-1 | - | 100 | - | - | 5.48 | 1 | - | |

| 90 | - | 10 | - | 3.48 | 1 | - | ||

| 90 | - | - | 10 | 5.00 | 5.55 | 1.11 | 1.69 | |

| (R/S)-2 | - | 100 | - | - | 1.00 | 1.24 | 1.24 | 1.73 |

| 90 | - | 10 | - | 2.62 | 1 | - | ||

| 90 | - | - | 10 | 4.24 | 5.07 | 1.19 | 2.08 | |

| (R/S)-3 | - | 100 | - | - | 0.53 | 1 | - | |

| 90 | - | 10 | - | 2.77 | 3.25 | 1.17 | 1.67 | |

| 90 | - | - | 10 | 3.84 | 1 | - | ||

| (R/S)-4 | - | 100 | - | - | 0.57 | 0.81 | 1.42 | 3.06 |

| 90 | - | 10 | - | 1.99 | 1 | - | ||

| 90 | - | - | 10 | 3.21 | 1 | - | ||

| (R/S)-5 | - | 100 | - | - | 0.35 | 1 | - | |

| 90 | - | 10 | - | 13.72 | 17.38 | 1.27 | 3.04 | |

| 90 | - | - | 10 | 14.68 | 18.55 | 1.26 | 2.95 | |

| (R/S)-6 | - | 100 | - | - | 0.96 | 1.27 | 1.32 | 2.49 |

| 90 | - | 10 | - | 8.90 | 10.45 | 1.18 | 3.22 | |

| 90 | - | - | 10 | 19.76 | 23.86 | 1.21 | 2.94 | |

| Compound | Mobile Phase | K1 | K2 | α | Rs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-hep (%) | MeOH (%) | EtOH (%) | IPA (%) | |||||

| (R/S)-1 | - | 100 | - | - | 2.5 | 1 | - | |

| - | 50 | 50 | - | 1.77 | 2.40 | 1.36 | 3.14 | |

| - | - | 100 | - | 1.03 | 1.63 | 1.58 | 3.25 | |

| 90 | - | - | 10 | 1.56 | 2.27 | 1.46 | 2.35 | |

| (R/S)-2 | - | 100 | - | - | 3.98 | 4.80 | 1.21 | 2.46 |

| - | 50 | 50 | - | 1.87 | 2.25 | 1.20 | 1.97 | |

| - | - | 100 | - | 1.23 | 1.46 | 1.19 | 1.83 | |

| 90 | - | - | 10 | 9.61 | 1 | - | ||

| (R/S)-3 | - | 100 | - | - | 1.24 | 1.80 | 1.45 | 4.05 |

| - | 50 | 50 | - | 0.70 | 0.93 | 1.33 | 2.32 | |

| - | - | 100 | - | 2.24 | 1 | - | ||

| 90 | - | - | 10 | 0.46 | 1 | - | ||

| (R/S)-4 | - | 100 | - | - | 1.52 | 1 | - | |

| - | 50 | 50 | - | 0.74 | 1 | - | ||

| - | - | 100 | - | 0.46 | 1 | - | ||

| 90 | - | - | 10 | 0.54 | 1 | - | ||

| (R/S)-5 | - | 100 | - | - | 1.10 | 1.61 | 1.46 | 2.62 |

| - | 50 | 50 | - | 0.74 | 1.07 | 1.45 | 1.99 | |

| - | - | 100 | - | 0.39 | 0.70 | 1.79 | 1.92 | |

| 90 | - | - | 10 | 0.32 | 1 | - | ||

| (R/S)-6 | - | 100 | - | - | 2.20 | 1 | - | |

| - | 50 | 50 | - | 1.25 | 1 | - | ||

| - | - | 100 | - | 0.73 | 1 | - | ||

| 90 | - | - | 10 | 0.61 | 1 | - | ||

| Compound | CSP | Processed Amount (mg) | No. Cycles | Enantiomer | Isolated Amount (mg) | ee (%) | Yield (%) | [α] (MeOH) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (R/S)-1 | Chiralcel OJ-H | 30 | 3 | (+)-1 | 14.1 | 96.0 | 94.0 | +40.5 |

| (−)-1 | 14.3 | 97.0 | 95.3 | −42.3 | ||||

| (R/S)-2 | Chiralcel OJ-H | 30 | 3 | (+)-2 | 13.8 | 95.0 | 92.0 | +6.1 |

| (−)-2 | 12.5 | 95.0 | 83.3 | −6.3 | ||||

| (R/S)-3 | Chiralcel OJ-H | 50 | 4 | (+)-3 | 22.9 | 99.9 | 91.6 | +10.5 |

| (−)-3 | 23.0 | 98.0 | 92.0 | −9.2 | ||||

| (R/S)-4 | Chiralpak IA | 16 | 2 | (+)-4 | 6.1 | 99.9 | 76.3 | +8.2 |

| (−)-4 | 6.3 | 99.9 | 78.8 | −8.3 | ||||

| (R/S)-5 | Chiralcel OJ-H | 22 | 4 | (+)-5 | 9.1 | 99.9 | 82.7 | +24.2 |

| (−)-5 | 8.9 | 99.9 | 80.9 | −24.8 | ||||

| (R/S)-6 | Chiralpak IA | 25 | 3 | (+)-6 | 10.5 | 99.9 | 84.0 | +11.8 |

| (−)-6 | 9.8 | 99.9 | 78.4 | −12.0 |

© 2016 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rui, M.; Marra, A.; Pace, V.; Juza, M.; Rossi, D.; Collina, S. Novel Enantiopure Sigma Receptor Modulators: Quick (Semi-)Preparative Chiral Resolution via HPLC and Absolute Configuration Assignment. Molecules 2016, 21, 1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21091210

Rui M, Marra A, Pace V, Juza M, Rossi D, Collina S. Novel Enantiopure Sigma Receptor Modulators: Quick (Semi-)Preparative Chiral Resolution via HPLC and Absolute Configuration Assignment. Molecules. 2016; 21(9):1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21091210

Chicago/Turabian StyleRui, Marta, Annamaria Marra, Vittorio Pace, Markus Juza, Daniela Rossi, and Simona Collina. 2016. "Novel Enantiopure Sigma Receptor Modulators: Quick (Semi-)Preparative Chiral Resolution via HPLC and Absolute Configuration Assignment" Molecules 21, no. 9: 1210. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21091210