Structure and Dynamics of Spider Silk Studied with Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Molecular Dynamics Simulation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

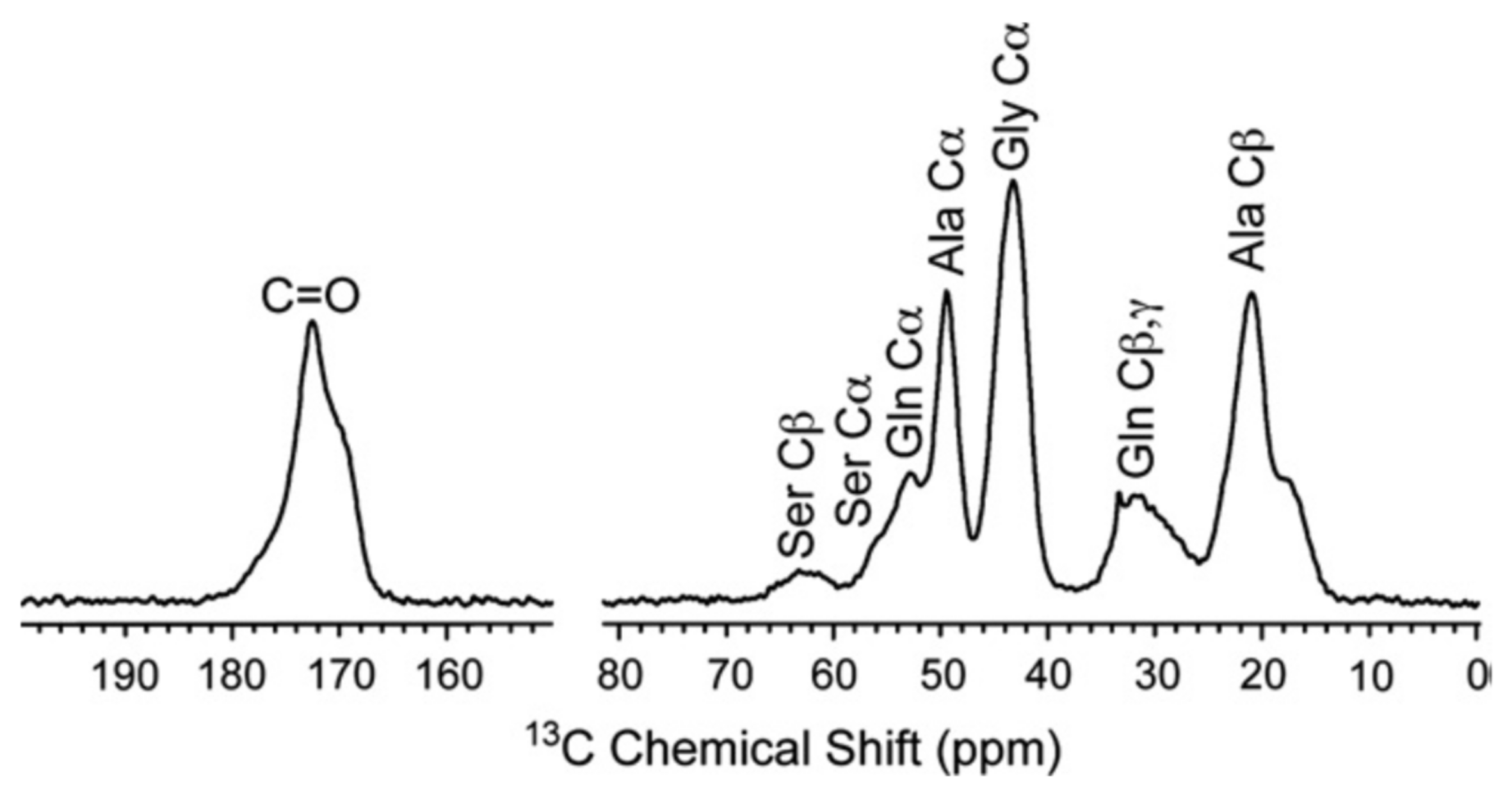

2. Major Ampullate Silk Fiber of N. clavipes and Their 13C Solid-State NMR Spectra

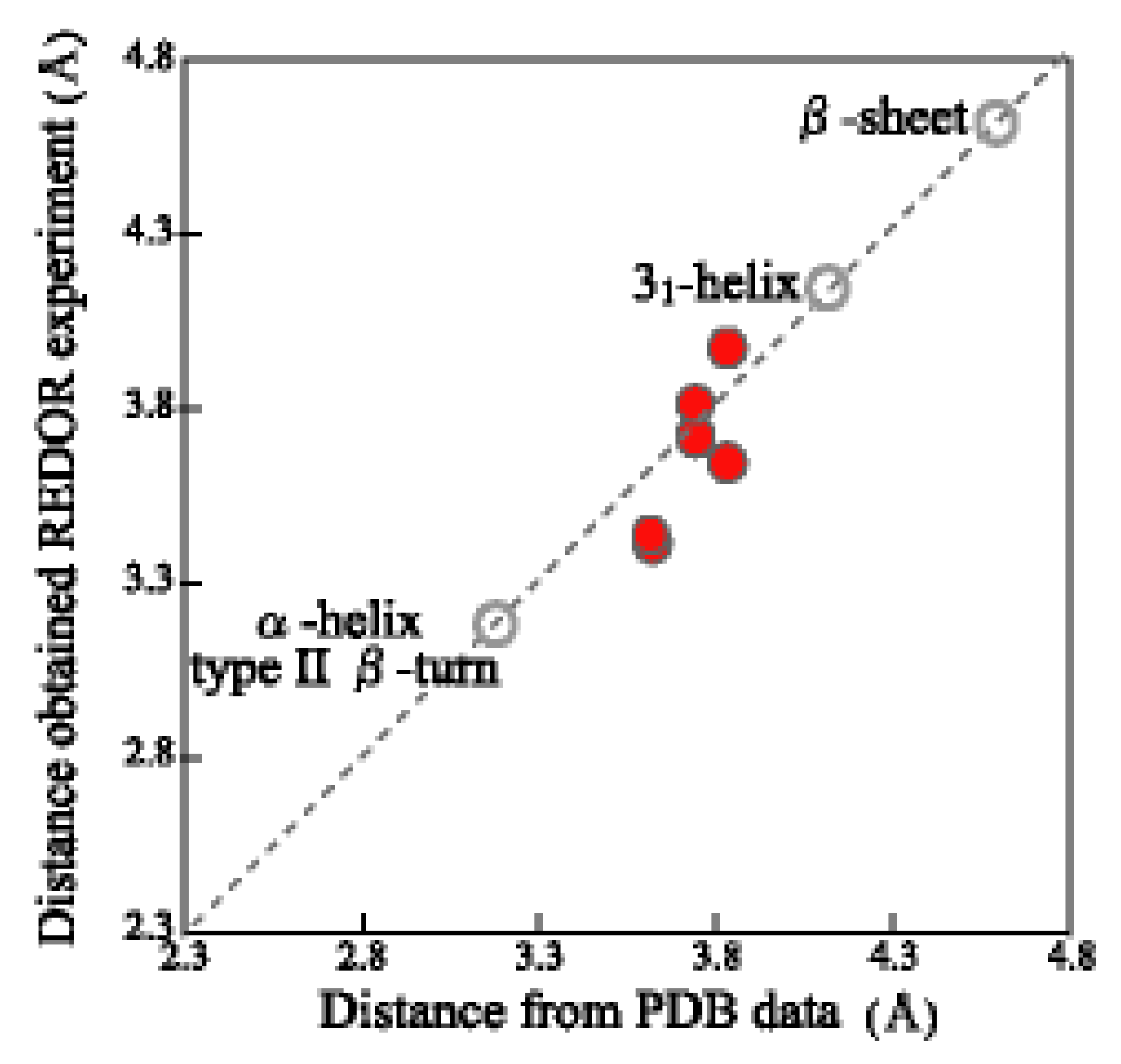

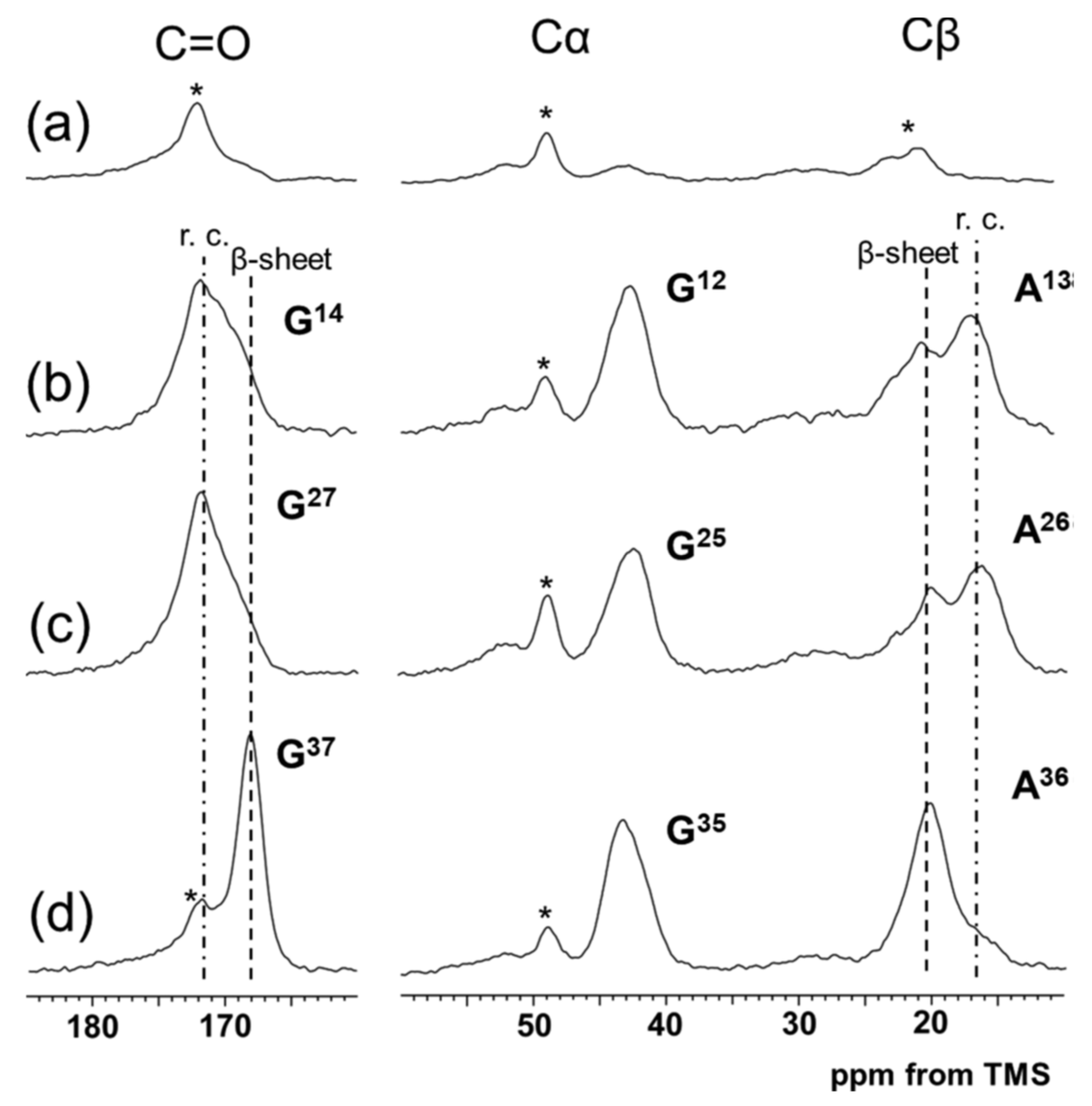

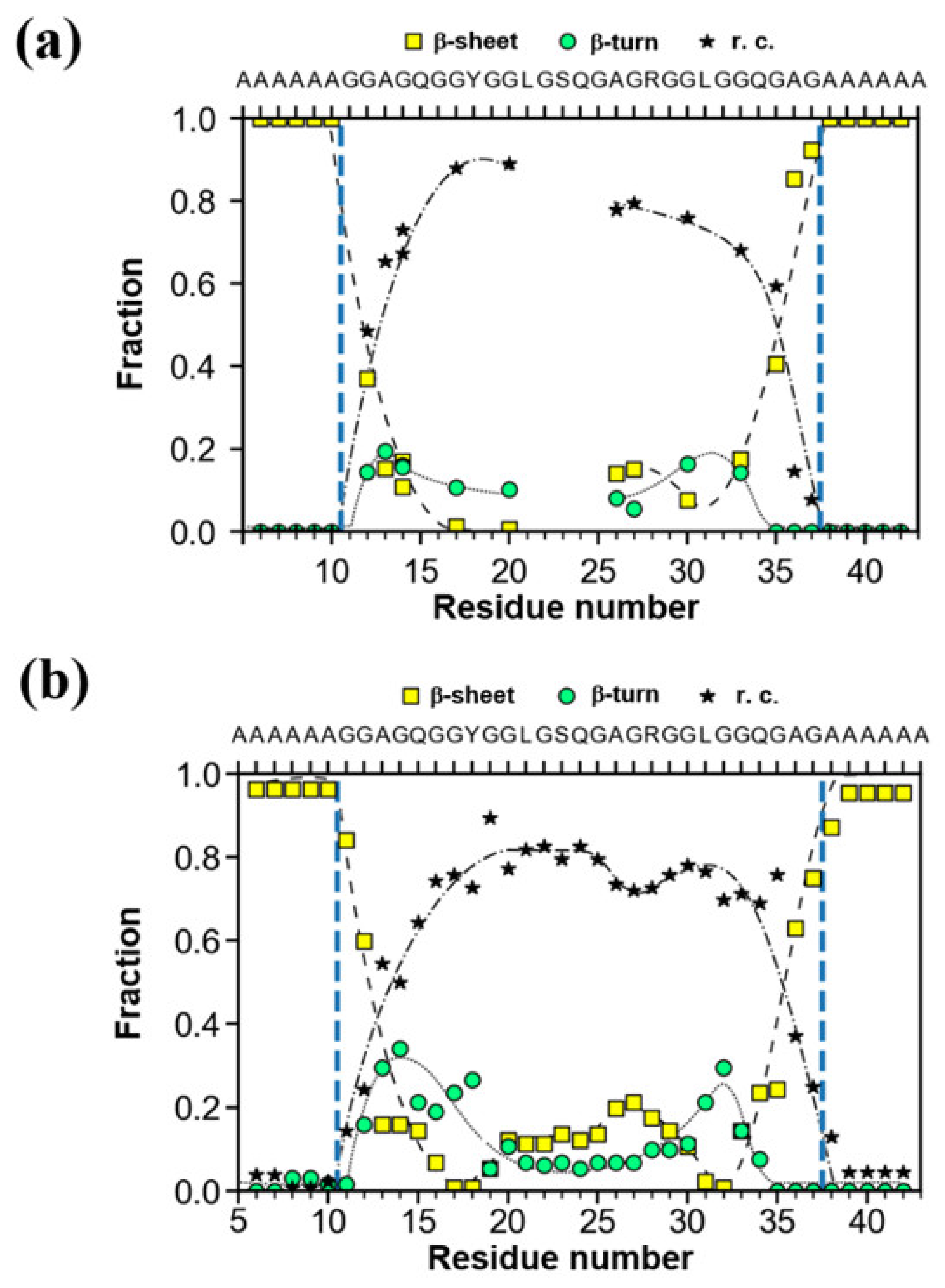

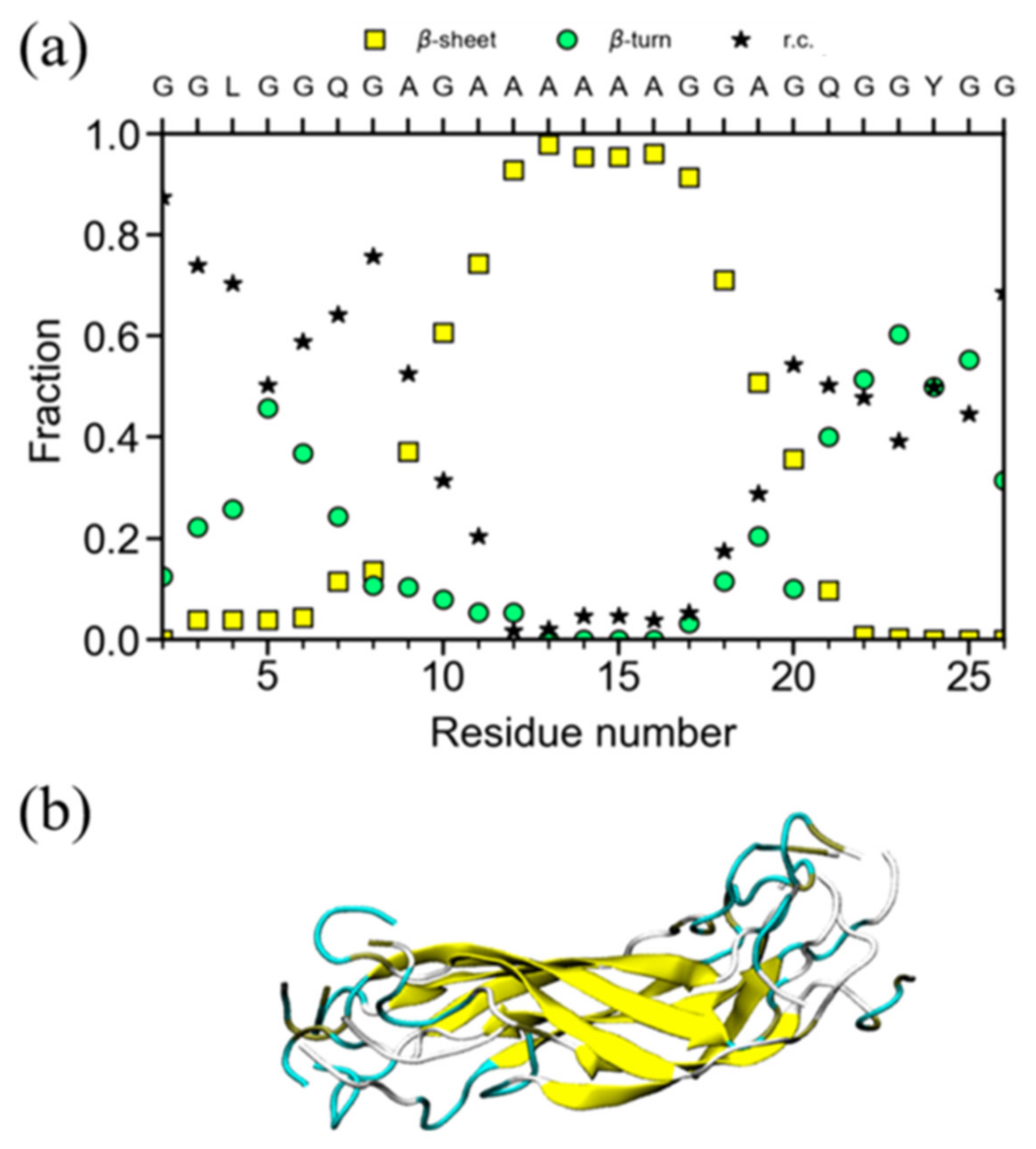

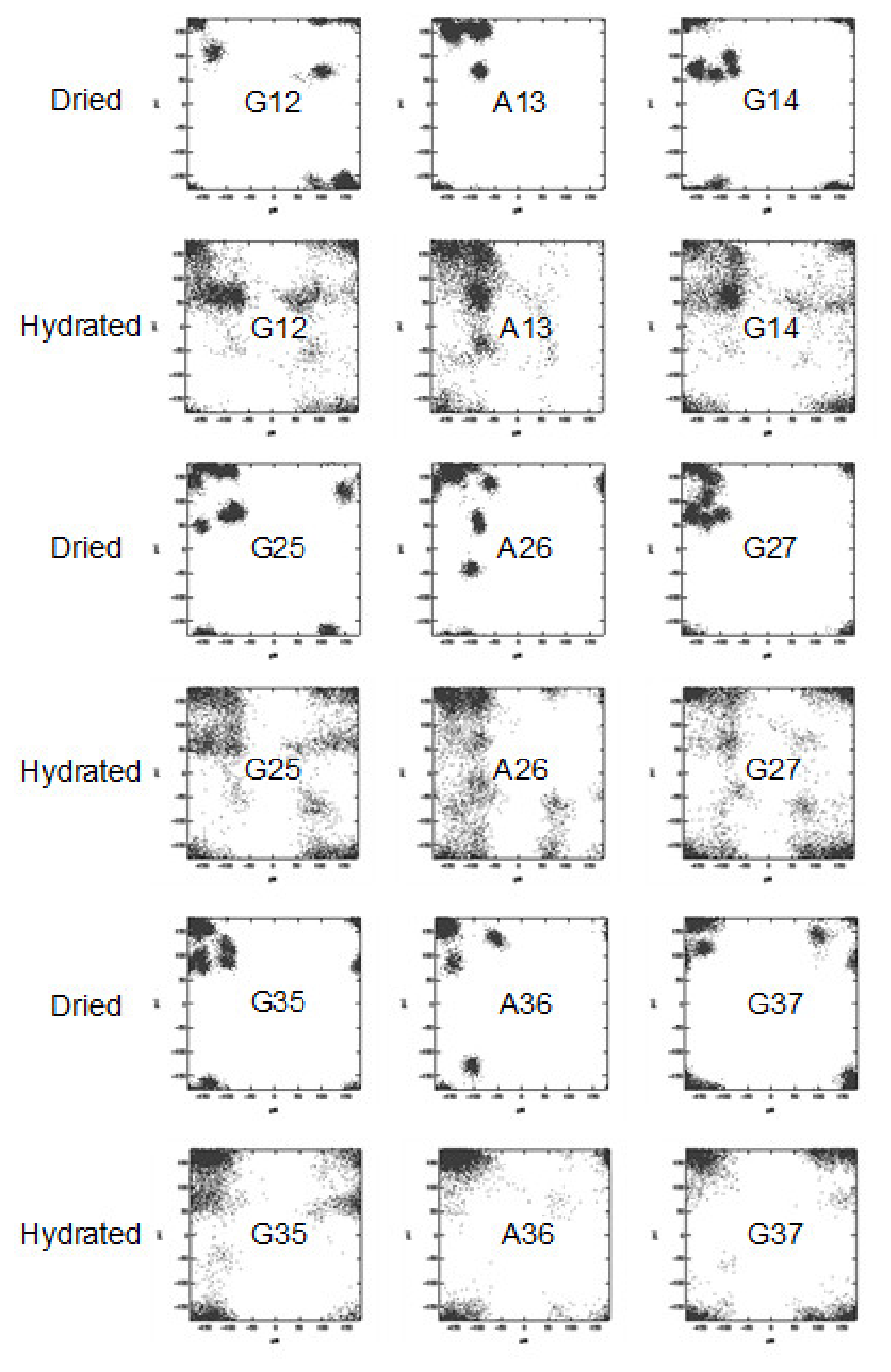

3. Structure of the Gly-Rich Region of N. clavipes Dragline Silk

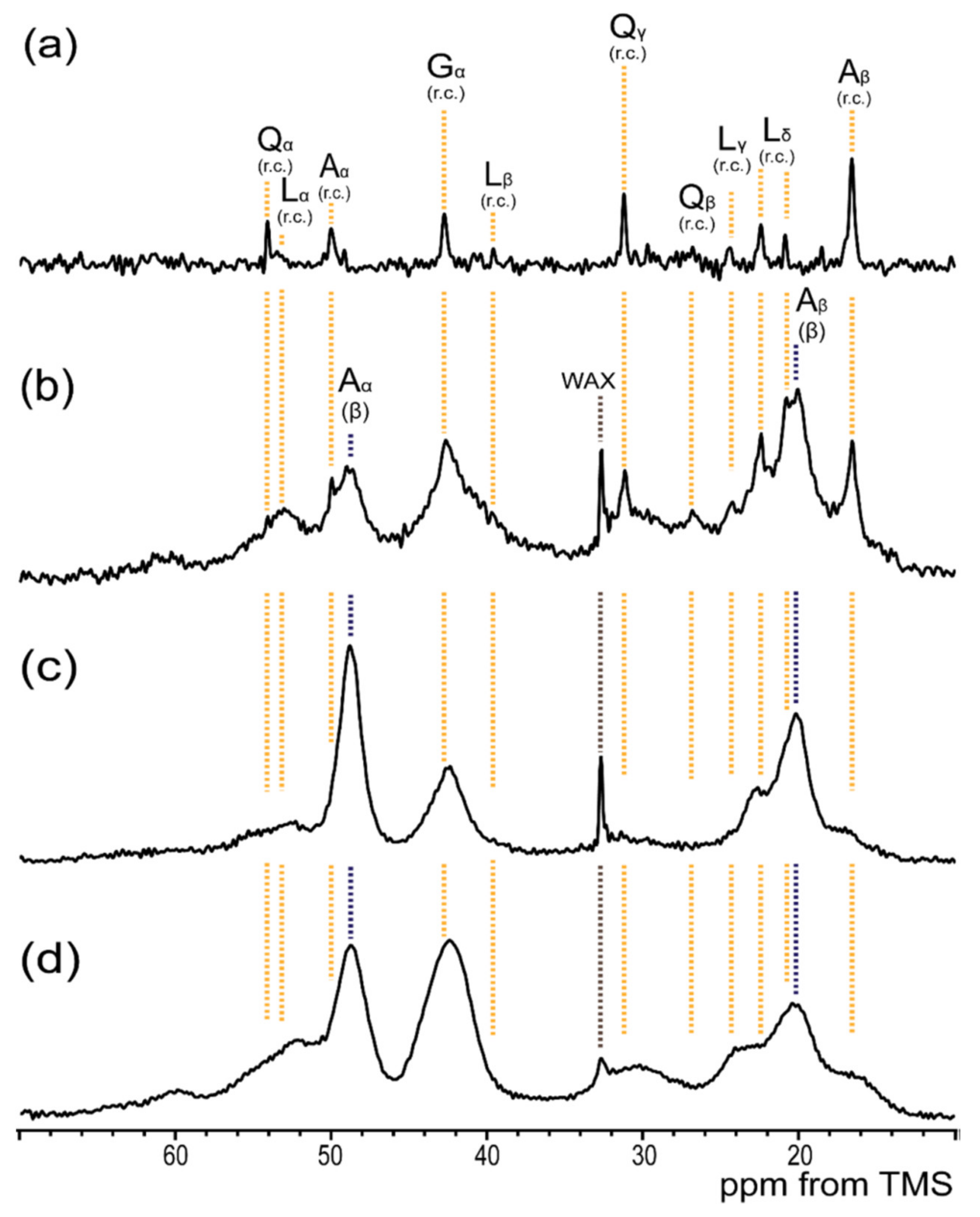

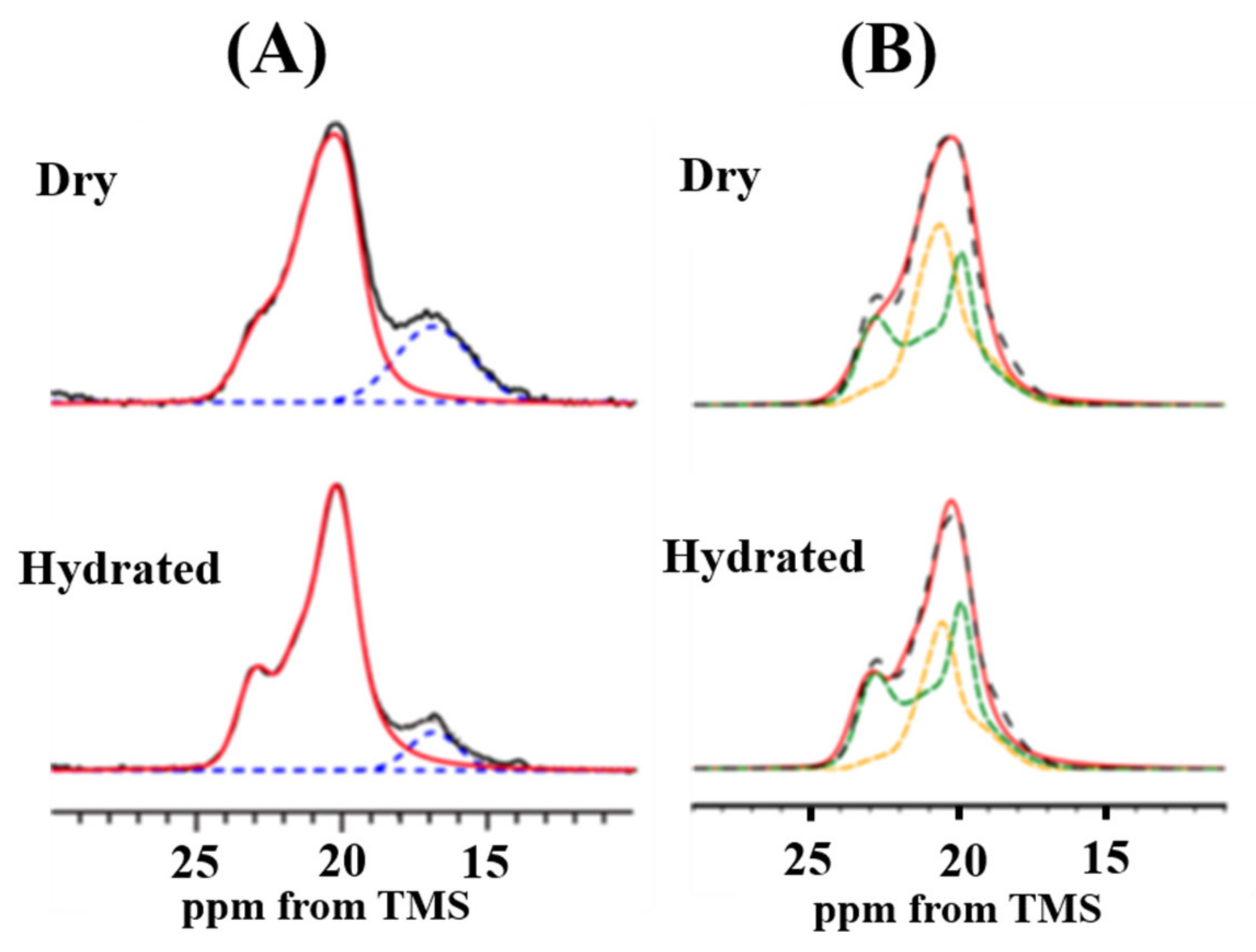

4. Packing Structure of the Polyalanine Region of N. clavipes Dragline Silk

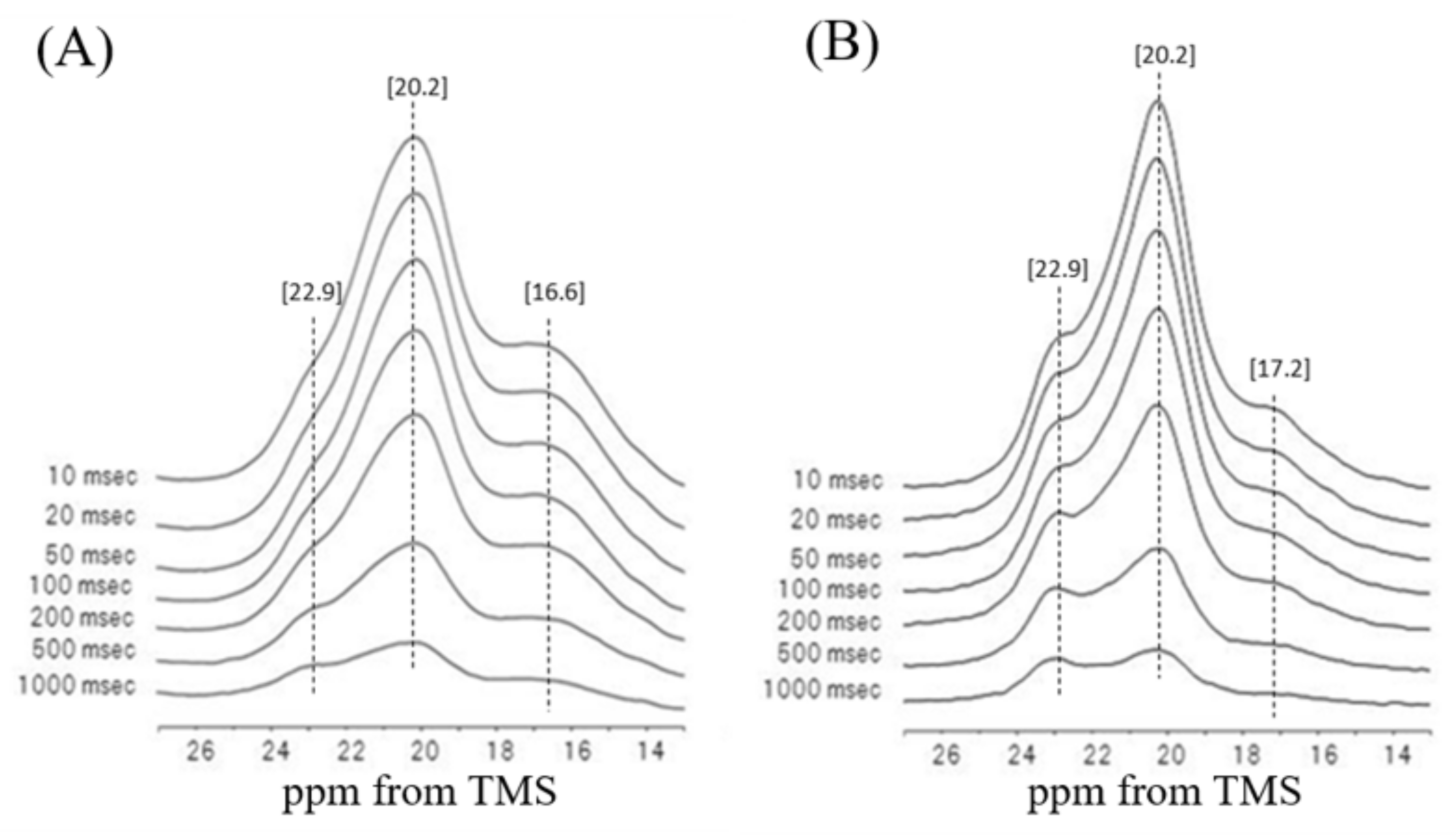

5. Dynamical Behavior and Hydration of N. clavipes Dragline Silk

6. Dynamical Behavior and Hydration of N. clavata Dragline Silk

7. Conclusions and Future Aspects

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fu, C.; Shao, Z.; Fritz, V. Animal silks: Their structures, properties, and artificial production. Chem. Commun. 2009, 37, 6515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asakura, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Kametani, S. Silk. Encycl. Polym. Sci. Technol. 2018, 124, 8794–8795. [Google Scholar]

- Gosline, J.M.; Demont, M.; Denny, M.W. The structure and properties of spider silk. Endeavour 1986, 10, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Lewis, R.V. Structure of a protein superfiber: Spider dragline silk. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 7120–7124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Eisoldt, L.; Smith, A.; Scheibel, T. Decoding the secrets of spider silk. Mater. Today 2011, 14, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokareva, O.; Jacobsen, M.M.; Buehler, M.; Wong, J.; Kaplan, D. Structure-function-property-design interplay in biopolymers: Spider silk. Acta Biomater. 2013, 10, 1612–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koh, L.-D.; Cheng, Y.; Teng, C.-P.; Khin, Y.-W.; Loh, X.-J.; Tee, S.-Y.; Low, M.; Ye, E.; Yu, H.-D.; Zhang, Y.-W.; et al. Structures, mechanical properties and applications of silk fibroin materials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2015, 46, 86–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Work, R.W. Viscoelastic Behaviour and Wet Supercontraction of Major Ampullate Silk Fibres of Certain Orb-Web-Building Spiders (Araneae). J. Exp. Biol. 1985, 118, 379–404. [Google Scholar]

- Savage, K.N.; Gosline, J. The effect of proline on the network structure of major ampullate silks as inferred from their mechanical and optical properties. J. Exp. Boil. 2008, 211, 1937–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Sponner, A.; Porter, D.; Vollrath, F. Proline and Processing of Spider Silks. Biomacromolecules 2008, 9, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigner, T.B.; de Simone, E.; Scheibel, T. Biomedical Applications of Recombinant Silk-Based Materials. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1704636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asakura, T.; Miller, T. Biotechnology of Silk. In Biologically-Inspired Systems; Asakura, T., Miller, T., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; ISBN 978-94-007-7118-5. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, F.; Shaw, J.T.; Smith, S.G. Comparative studies of fibroins I. The amino acid composition of various fibroins and its significance in relation to their crystal structure and taxonomy. J. Mol. Boil. 1960, 2, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Work, R.W.; Young, C.T. The Amino Acid Compositions of Major and Minor Ampullate Silks of Certain Orb-Web-Building Spiders (Araneae, Araneidae). J. Arachnol. 1987, 15, 65–80. [Google Scholar]

- Grubb, D.T.; Jelinski, L.W. Fiber Morphology of Spider Silk: The Effects of Tensile Deformation. Macromolecules 1997, 30, 2860–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riekel, C.; Müller, M.; Vollrath, F. In Situ X-ray Diffraction during Forced Silking of Spider Silk. Macromolecules 1999, 32, 4464–4466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riekel, C.; Madsen, B.; Knight, D.; Vollrath, F. X-ray diffraction on spider silk during controlled extrusion under a synchrotron radiation X-ray beam. Biomacromolecules 2000, 1, 622–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trancik, J.; Czernuszka, J.; Bell, F.; Viney, C. Nanostructural features of a spider dragline silk as revealed by electron and X-ray diffraction studies. Polymer 2006, 47, 5633–5642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glišović, A.; Salditt, T. Temperature dependent structure of spider silk by X-ray diffraction. Appl. Phys. A 2007, 87, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, M.-E.; Hernández-Cruz, D.; West, M.M.; Hitchcock, A.P.; Pézolet, M. Nephila clavipes Spider Dragline Silk Microstructure Studied by Scanning Transmission X-ray Microscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 3897–3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampath, S.; Isdebski, T.; Jenkins, J.E.; Ayon, J.V.; Henning, R.W.; Orgel, J.P.R.O.; Antipoa, O.; Yarger, J.L. X-ray diffraction study of nanocrystalline and amorphous structure within major and minor ampullate dragline spider silks. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 6713–6722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benmore, C.J.; Izdebski, T.; Yarger, J.L. Total X-Ray Scattering of Spider Dragline Silk. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 178102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Madurga, R.; Blackledge, T.A.; Perea, B.; Plaza, G.R.; Riekel, C.; Burghammer, M.; Elices, M.; Guinea, G.; Pérez-Rigueiro, J. Persistence and variation in microstructural design during the evolution of spider silk. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riekel, C.; Burghammer, M.; Dane, T.; Ferrero, C.; Rosenthal, M. Nanoscale Structural Features in Major Ampullate Spider Silk. Biomacromolecules 2016, 18, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazawa, K.; Malay, A.D.; Masunaga, H.; Norma-Rashid, Y.; Numata, K. Simultaneous effect of strain rate and humidity on the structure and mechanical behavior of spider silk. Commun. Mater. 2020, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Simmons, A.; Ray, E.; Jelinski, L.W. Solid-State 13C NMR of Nephila clavipes Dragline Silk Establishes Structure and Identity of Crystalline Regions. Macromolecules 1994, 27, 5235–5237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, A.H.; Michal, C.A.; Jelinski, L.W. Molecular Orientation and Two-Component Nature of the Crystalline Fraction of Spider Dragline Silk. Science 1996, 271, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kümmerlen, J.; van Beek, J.D.; Vollrath, F.; Meier, B.H. Local Structure in Spider Dragline Silk Investigated by Two-Dimensional Spin-Diffusion Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Macromolecules 1996, 29, 2920–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michal, C.A.; Jelinski, L.W. Rotational-echo double-resonance in complex biopolymers: A study of Nephila clavipes dragline silk. J. Biomol. NMR 1998, 12, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Liivak, O.; Seidel, A.; LaVerde, G.; Zax, D.B.; Jelinski, L.W. Supercontraction and Backbone Dynamics in Spider Silk: 13C and 2H NMR Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 9019–9025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishore, A.I.; Herberstein, M.; Craig, C.L.; Separovic, F. Solid-state NMR relaxation studies of Australian spider silks. Biopolymers 2002, 61, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Beek, J.D.; Hess, S.; Vollrath, F.; Meier, B.H. The molecular structure of spider dragline silk: Folding and orientation of the protein backbone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 10266–10271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ashida, J.; Ohgo, K.; Komatsu, K.; Kubota, A.; Asakura, T. Determination of the torsion angles of alanine and glycine residues of model compounds of spider silk (AGG) 10 using solid-state NMR methods. J. Biomol. NMR 2003, 25, 91–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eles, P.T.; Michal, C.A. A Decoder NMR Study of Backbone Orientation in Nephila clavipes Dragline Silk under Varying Strain and Draw Rate. Biomacromolecules 2004, 5, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eles, P.T.; Michal, C.A. Strain Dependent Local Phase Transitions Observed during Controlled Supercontraction Reveal Mechanisms in Spider Silk. Macromolecules 2004, 37, 1342–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hronska, M.; van Beek, J.D.; Williamson, P.T.F.; Vollrath, F.; Meier, B.H. NMR Characterization of Native Liquid Spider Dragline Silk from Nephila edulis. Biomacromolecules 2004, 5, 834–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, G.P.; Lewis, R.V.; Yarger, J.L. Wise NMR Characterization of Nanoscale Heterogeneity and Mobility in Supercontracted Nephila clavipes Spider Dragline Silk. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 5867–5872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, T.; Yang, M.; Kawase, T.; Nakazawa, Y. 13C Solid-State NMR Study of Structural Heterogeneity in Peptides Containing Both Polyalanine and Repeated GGA Sequences as a Local Structural Model of Nephila clavipes Dragline Silk (Spidroin 1). Macromolecules 2005, 38, 3356–3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Nakazawa, Y.; Yamauchi, K.; Knight, D.P.; Asakura, T. Structure of model peptides based on Nephila clavipes dragline silk spidroin (MaSp1) studied by 13C cross polarization/magic angle spinning NMR. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 3220–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonev, B.B.; Grieve, S.M.; Herberstein, M.; Kishore, A.I.; Watts, A.; Separovic, F. Orientational order of Australian spider silks as determined by solid-state NMR. Biopolymer 2006, 82, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohgo, K.; Kawase, T.; Ashida, J.; Asakura, T. Solid-State NMR Analysis of a Peptide (Gly-Pro-Gly-Gly-Ala)6-Gly Derived from a Flagelliform Silk Sequence of Nephila clavipes. Biomacromolecules 2006, 7, 1210–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcotte, I.; van Beek, J.D.; Meier, B.H. Molecular Disorder and Structure of Spider Dragline Silk Investigated by Two-Dimensional Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. Macromolecules 2007, 40, 1995–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, G.P.; Jenkins, J.E.; Creager, M.S.; Lewis, R.V.; Yarger, J.L. Solid-State NMR Investigation of Major and Minor Ampullate Spider Silk in the Native and Hydrated States. Biomacromolecules 2008, 9, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, G.P.; Creager, M.S.; Jenkins, J.E.; Lewis, R.V.; Yarger, J.L. Determining Secondary Structure in Spider Dragline Silk by Carbon−Carbon Correlation Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 9871–9877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, G.P.; Jenkins, J.E.; Creager, M.S.; Lewis, R.V.; Yarger, J.L. Quantifying the fraction of glycine and alanine in β-sheet and helical conformations in spider dragline silk using solid-state NMR. Chem. Commun. 2008, 5568–5570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yamaguchi, E.; Yamauchi, K.; Gullion, T.; Asakura, T. Structural analysis of the Gly-rich region in spider dragline silk using stable-isotope labeled sequential model peptides and solid-state NMR. Chem. Commun. 2009, 4176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, J.E.; Creager, M.S.; Butler, E.B.; Lewis, R.V.; Yarger, J.L.; Holland, G.P. Solid-state NMR evidence for elastin-like β-turn structure in spider dragline silk. Chem. Commun. 2010, 46, 6714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, J.E.; Creager, M.S.; Lewis, R.V.; Holland, G.P.; Yarger, J.L. Quantitative Correlation between the Protein Primary Sequences and Secondary Structures in Spider Dragline Silks. Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Izdebski, T.; Akhenblit, P.; Jenkins, J.E.; Yarger, J.L.; Holland, G.P. Structure and Dynamics of Aromatic Residues in Spider Silk: 2D Carbon Correlation NMR of Dragline Fibers. Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, G.P.; Cherry, B.R.; Jenkins, J.E.; Yarger, J.L. Proton-detected heteronuclear single quantum correlation NMR spectroscopy in rigid solids with ultra-fast MAS. J. Magn. Reson. 2009, 202, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yazawa, K.; Yamaguchi, E.; Knight, D.; Asakura, T. 13C solid-state NMR study of the 13C-labeled peptide, (E)8GGLGGQGAG(A)6GGAGQGGYGG as a model for the local structure of Nephila clavipes dragline silk (MaSp1) before and after spinning. Biopolymers 2011, 97, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, T.; Okonogi, M.; Horiguchi, K.; Aoki, A.; Saitô, H.; Knight, D.P.; Williamson, M.P. Two Different Packing Arrangements of Antiparallel Polyalanine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 1212–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, J.E.; Sampath, S.; Butler, E.; Kim, J.; Henning, R.W.; Holland, G.P.; Yarger, J.L. Characterizing the Secondary Protein Structure of Black Widow Dragline Silk Using Solid-State NMR and X-ray Diffraction. Biomacromolecules 2013, 14, 3472–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shi, X.; Yarger, J.L.; Holland, G.P. Elucidating proline dynamics in spider dragline silk fibre using 2H-13C HETCOR MAS NMR. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 4856–4859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xu, D.; Shi, X.; Thompson, F.; Weber, W.S.; Mou, Q.; Yarger, J.L. Protein secondary structure of Green Lynx spider dragline silk investigated by solid-state NMR and X-ray diffraction. Int. J. Boil. Macromol. 2015, 81, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gray, G.M.; van der Vaart, A.; Guo, C.; Jones, J.; Onofrei, D.; Cherry, B.R.; Lewis, R.V.; Yarger, J.L.; Holland, G.P. Secondary Structure Adopted by the Gly-Gly-X Repetitive Regions of Dragline Spider Silk. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tasei, Y.; Nishimura, A.; Suzuki, Y.; Sato, T.K.; Sugahara, J.; Asakura, T. NMR Investigation about Heterogeneous Structure and Dynamics of Recombinant Spider Silk in the Dry and Hydrated States. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 8117–8128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kametani, S.; Tasei, Y.; Nishimura, A.; Asakura, T. Distinct solvent- and temperature-dependent packing arrangements of anti-parallel β-Sheet polyalanines studied with solid-state 13 C NMR and MD simulation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 20829–20838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, T.; Tasei, Y.; Aoki, A.; Nishimura, A. Mixture of Rectangular and Staggered Packing Arrangements of Polyalanine Region in Spider Dragline Silk in Dry and Hydrated States as Revealed by 13C NMR and X-ray Diffraction. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 1058–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, T.; Matsuda, H.; Kataoka, N.; Imai, A. Changes in the Local Structure of Nephila clavipes Dragline Silk Model Peptides upon Trifluoroacetic Acid, Low pH, Freeze-Drying, and Hydration Treatments Studied by 13C Solid-State NMR. Biomacromolecules 2018, 19, 4396–4410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, T.; Tasei, Y.; Matsuda, H.; Naito, A. Dynamics of Alanine Methyl Groups in Alanine Oligopeptides and Spider Dragline Silks with Different Packing Structures as Studied by 13C Solid-State NMR Relaxation. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 6746–6756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, T.; Nishimura, A.; Tasei, Y. Determination of Local Structure of 13C Selectively Labeled 47-mer Peptides as a Model for Gly-Rich Region of Nephila clavipes Dragline Silk Using a Combination of 13C Solid-State NMR and MD Simulation. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 3608–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, T.; Nishimura, A.; Aoki, A.; Naito, A. Packing Structure of Antiparallel β-Sheet Polyalanine Region in a Sequential Model Peptide of Nephila clavipes Dragline Silk Studied Using 13C Solid-State NMR and MD Simulation. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20, 3884–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, T.; Okonogi, M.; Naito, A. Toward Understanding the Silk Fiber Structure: 13C Solid-State NMR Studies of the Packing Structures of Alanine Oligomers before and after Trifluoroacetic Acid Treatment. J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 123, 6716–6727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asakura, T.; Matsuda, H.; Aoki, A.; Kataoka, N.; Imai, A. Conformational change of 13C-labeled 47-mer model peptides of Nephila clavipes dragline silk in poly(vinyl alcohol) film by stretching studied by 13C solid-state NMR and molecular dynamics simulation. Int. J. Boil. Macromol. 2019, 131, 654–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asakura, T.; Okushita, K.; Williamson, M.P. Analysis of the Structure of Bombyx mori Silk Fibroin by NMR. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 2345–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitô, H. Conformation-dependent 13C chemical shifts: A new means of conformational characterization as obtained by high-resolution solid-state 13C NMR. Magn. Reson. Chem. 1986, 24, 835–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitô, H.; Ando, I. High-Resolution Solid-State NMR Studies of Synthetic and Biological Macromolecules. Ann. Rep. NMR Spectrosc. 1989, 21, 209–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spera, S.; Bax, A. Empirical correlation between protein backbone conformation and Cα and Cβ 13C nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shifts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 5490–5492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwadate, M.; Asakura, T.; Williamson, M.P. Cα and Cβ Carbon-13 Chemical Shifts in Proteins from an Empirical Database. J. Biomol. NMR 1999, 13, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, T.; Iwadate, M.; Demura, M.; Williamson, M.P. Structural analysis of silk with 13C NMR chemical shift contour plots. Int. J. Boil. Macromol. 1999, 24, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wishart, D.S. Interpreting protein chemical shift data. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2011, 58, 62–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamane, T.; Umemura, K.; Asakura, T. The Structural Characteristics of Bombyx mori Silk Fibroin before Spinning as Studied with Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 8831–8838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, T.; Umemura, K.; Nakazawa, Y.; Asakura, T. Molecular dynamics simulation of conformational change of poly (Ala-Gly) from silk I to silk II in relation to fiber formation mechanism of Bombyx mori silk fibroin. Macromolecules 2003, 36, 6766–6772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Zhang, M. Molecular dynamics simulations of alanine rich β-sheet oligomers: Insight into amyloid formation. Protein Sci. 2009, 11, 2335–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keten, S.; Buehler, M.J. Nanostructure, and molecular mechanics of spider dragline silk protein assemblies. J. R. Soc. Interface 2010, 7, 1709–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bratzel, G.; Buehler, M.J. Sequence-structure correlations in silk: Poly-Ala repeat of N. clavipes MaSp1 is naturally optimized at a critical length scale. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2012, 7, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, S.P.; Markert, B.; Gräter, F. Rate-Dependent Behavior of the Amorphous Phase of Spider Dragline Silk. Biophys. J. 2014, 106, 2511–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cheng, Y.; Koh, L.-D.; Li, D.; Ji, B.; Han, M.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-W. On the strength of β-sheet crystallites of Bombyx mori silk fibroin. J. R. Soc. Interface 2014, 11, 20140305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ukpebor, O.T.; Shah, A.; Bazov, E.; Boutis, G.S.; Bazov, E. Inverse temperature transition of elastin like motifs in major ampullate dragline silk: MD simulations of short peptides and NMR studies of water dynamics. Soft Matter 2014, 10, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giesa, T.; Perry, C.C.; Buehler, M.J. Secondary Structure Transition and Critical Stress for a Model of Spider Silk Assembly. Biomacromolecules 2016, 17, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sintya, E.; Alam, P. Self-assembled semi-crystallinity at parallel β -sheet nanocrystal interfaces in clustered MaSp1 (spider silk) proteins. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 58, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giesa, T.; Schuetz, R.; Fratzl, P.; Buehler, M.J.; Masic, A. Unraveling the Molecular Requirements for Macroscopic Silk Supercontraction. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 9750–9758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Tarakanova, A.; Hsu, C.C.; Yu, M.; Zheng, S.; Yu, L.; Liu, J.; He, Y.; Dunstan, D.J.; Buehler, M.J. Spider dragline silk as torsional actuator driven by humidity. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, e9183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Patel, M.; Dubey, D.K.; Singh, S.P. Phenomenological models of Bombyx mori silk fibroin and their mechanical behavior using molecular dynamics simulations. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 108, 110414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Han, S. Structure of Silk studied with NMR. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2001, 39, 301–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameda, T.; Asakura, T. Dynamics of silk fibroin studied with NMR spectroscopy. Ann. Rep. NMR Spectrosc. 2002, 46, 101–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, T.; Nakazawa, Y. Structure and Structural Changes of the Silk Fibroin from Samia cynthia ricini Using Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy. Macromol. Biosci. 2004, 4, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Nakazawa, Y.; Yazawa, K.; Holland, G.P.; Yarger, J.L. Silk structure studied with nuclear magnetic resonance. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2013, 69, 23–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Nakazawa, Y.; Holland, G.P.; Yarger, J.L. Elucidating silk structure using solid-state NMR. Soft Matter 2013, 9, 11440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, T.; Tasei, Y. NMR Studies on Silk Materials. In Experimental Approaches of NMR Spectroscopy; Springer Science and Business Media LLC: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 297–312. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, C.; Yarger, J.L. Chapter 18. NMR Characterization of Silk. In New Developments in NMR; Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC): London, UK, 2019; pp. 420–456. [Google Scholar]

- Hinman, M.B.; Lewis, R. V Isolation of a clone encoding a second dragline silk fibroin. Nephila clavipes dragline silk is a two-protein fiber. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 19320–19324. [Google Scholar]

- Nagano, A.; Sato, H.; Tanioka, Y.; Nakazawa, Y.; Knight, D.; Asakura, T. Characterization of a Ca binding-amphipathic silk-like protein and peptide with the sequence (Glu)8(Ala-Gly-Ser-Gly-Ala-Gly)4 with potential for bone repair. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullion, T.; Schaefer, J. Rotational-echo double-resonance NMR. J. Magn. Reson. 1989, 81, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Gullion, T.; Schaefer, J. Determination of CN internuclear distances by rotational-echo double-resonance NMR of solids. J. Magn. Reson. 1990, 90, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotz, B.; Keith, H. The crystal structures of poly (lAla-Gly-Gly-Gly) II and poly (lAla-Gly-Gly) II. J. Mol. Boil. 1971, 61, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.-K.; Ramamoorthy, A. Determination of the Solid-State Conformations of Polyalanine Using Magic-Angle Spinning NMR Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henzler-Wildman, K.; Lee, N.-K.; Ramamoorthy, A. Determination of α-helix and β-sheet stability in the solid state: A solid-state NMR investigation of poly (L-alanine). Biopolymer 2002, 64, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Burum, D.; Ernst, R. Net polarization transfer via a J-ordered state for signal enhancement of low-sensitivity nuclei. J. Magn. Reson. 1980, 39, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, T.; Sato, Y.; Aoki, A. Stretching-Induced Conformational Transition of the Crystalline and Noncrystalline Domains of 13C-Labeled Bombyx mori Silk Fibroin Monitored by Solid State NMR. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 5761–5769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, T.; Isobe, K.; Aoki, A.; Kametani, S. Conformation of Crystalline and Noncrystalline Domains of [3-13C]Ala-, [3-13C]Ser-, and [3-13C] Tyr-Bombyx mori Silk Fibroin in a Hydrated State Studied with 13C DD/MAS NMR. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 8062–8069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitô, H.; Tuzi, S.; Tanio, M.; Naito, A. Dynamic aspects of membrane proteins and membrane-associated peptides as revealed by 13C NMR: Lessons from bacteriorhodopsin as an intact protein. In Annual Reports on NMR Spectroscopy; Elsevier BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 39–108. [Google Scholar]

- Asakura, T.; Endo, M.; Tasei, Y.; Ohkubo, T.; Hiraoki, T. Hydration of Bombyx mori silk cocoon, silk sericin and silk fibroin and their interactions with water as studied by 13C NMR and 2H NMR relaxation. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 1624–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, T.; Endo, M.; Fukuhara, R.; Tasei, Y. 13C NMR characterization of hydrated 13C labeled Bombyx mori silk fibroin sponges prepared using glycerin, poly(ethylene glycol diglycidyl ether) and poly(ethylene glycol) as porogens. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 2152–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, A.; Zhao, T.; Sima, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Nakagaki, K.; Miao, Y.; Shiomi, K.; Kajiura, Z.; Nagata, Y.; Nakagaki, M. Unique Molecular Architecture of Egg Case Silk Protein in a Spider, Nephila clavata. J. Biochem. 2005, 138, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Shimizu, K.; Shiomi, K.; Kajiura, Z.; Nakagawa, M. cDNA cloning of Nephila clavata dragline silk (MaSp1) gene and comparison with the sequence of Bombyx mori fibroin heavy chain. Sanshi-Konchu Biotec. 2008, 77, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, A.; Ganapathy, S.; Akasaka, K.; McDowell, C. Spin-lattice relaxation of 13C in solid amino acids using the CP-MAS technique. J. Magn. Reson. 1983, 54, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, A.; Fukutani, A.; Uitdehaag, M.; Tuzi, S.; Saitô, H. Backbone dynamics of polycrystalline peptides studied by measurements of 15N NMR lineshapes and 13C transverse relaxation times. J. Mol. Struct. 1998, 441, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, A.; Tasei, Y.; Nishimura, A.; Asakura, T. Unusual Dynamics of Alanine Residues in Polyalanine Regions with Staggered Packing Structure of Samia cynthia ricini Silk Fiber in Dry and Hydrated States Studied by 13C Solid-State NMR and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 6511–6520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnott, S.; Dover, S.; Elliott, A. Structure of β-poly-l-alanine: Refined atomic co-ordinates for an anti-parallel beta-pleated sheet. J. Mol. Boil. 1967, 30, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, T.; Nishimura, A.; Kametani, S.; Kawanishi, S.; Aoki, A.; Suzuki, F.; Kaji, H.; Naito, A. Refined Crystal Structure of Samia cynthia ricini Silk Fibroin Revealed by Solid-State NMR Investigations. Biomacromolecules 2017, 18, 1965–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, T.; Miyazawa, K.; Tasei, Y.; Kametani, S.; Nakazawa, Y.; Aoki, A.; Naito, A. Packing arrangement of 13 C selectively labeled sequence model peptides of Samia cynthia ricini silk fibroin fibers studied by solid-state NMR. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 13379–13386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blamires, S.J.; Blackledge, T.A.; Tso, I.-M. Physicochemical Property Variation in Spider Silk: Ecology, Evolution, and Synthetic Production. Annu. Rev. Èntomol. 2017, 62, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, H.C.; Blamires, S.J.; Sani, M.-A.; Kasumovic, M.M.; Rawal, A.; Hook, J.M. DNP NMR spectroscopy reveals new structures, residues, and interactions in wild spider silks. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 4687–4690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| I: | REDOR and 13C CP/MAS NMR Experiments | Distance * |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | (E)4(A)6GGAGQGGYGGLGSQGAGRGGLGGQGAG(A)6(E)4 | |

| 2 | (E)4(A)6GGA[1-13C]G14Q[15N]G15GYGGLGSQGAGRGGLGGQGAG(A)6(E)4 | 3.71 Å |

| 3 | (E)4(A)6GGAGQG[1-13C]G17Y[15N]G19GLGSQGAGRGGLGGQGAG(A)6(E)4 | 3.97 Å |

| 4 | (E)4(A)6GGAGQGGYG[1-13C]G20L[15N]G22SQGAGRGGLGGQGAG(A)6(E)4 | 3.41 Å |

| 5 | (E)4(A)6GGAGQGGYGGLGSQGA[1-13C]G27R[15N]G29GLGGQGAG(A)6(E)4 | 3.64 Å |

| 6 | (E)4(A)6GGAGQGGYGGLGSQGAGRG[1-13C]G30L[15N]G32GQGAG(A)6(E)4 | 3.43 Å |

| 7 | (E)4(A)6GGAGQGGYGGLGSQGAGRGGLG[1-13C]G33Q[15N]35GAG(A)6(E)4 | 3.81 Å |

| II: | 13C CP/MAS NMR Experiment | |

| 8 | (E)4(A)6G [2-13C]G12 [3-13C]A13 [1-13C]G14QGGYGGLGSQGAGRGGLGGQGAG(A)6(E)4 | |

| 9 | (E)4(A)6GGAGQGGYGGLGSQ [2-13C]G25 [3-13C]A26 [1-13C]G27RGGLGGQGAG(A)6(E)4 | |

| 10 | (E)4(A)6GGAGQGGYGGLGSQGAGRGGLGGQ [2-13C]G35 [3-13C]A36 [1-13C]G37(A)6(E)4 | |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Asakura, T. Structure and Dynamics of Spider Silk Studied with Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Molecules 2020, 25, 2634. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25112634

Asakura T. Structure and Dynamics of Spider Silk Studied with Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Molecules. 2020; 25(11):2634. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25112634

Chicago/Turabian StyleAsakura, Tetsuo. 2020. "Structure and Dynamics of Spider Silk Studied with Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance and Molecular Dynamics Simulation" Molecules 25, no. 11: 2634. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules25112634