Phytoalexin Accumulation in Colombian Bean Varieties and Aminosugars as Elicitors

Abstract

:Introduction

Results and Discussion

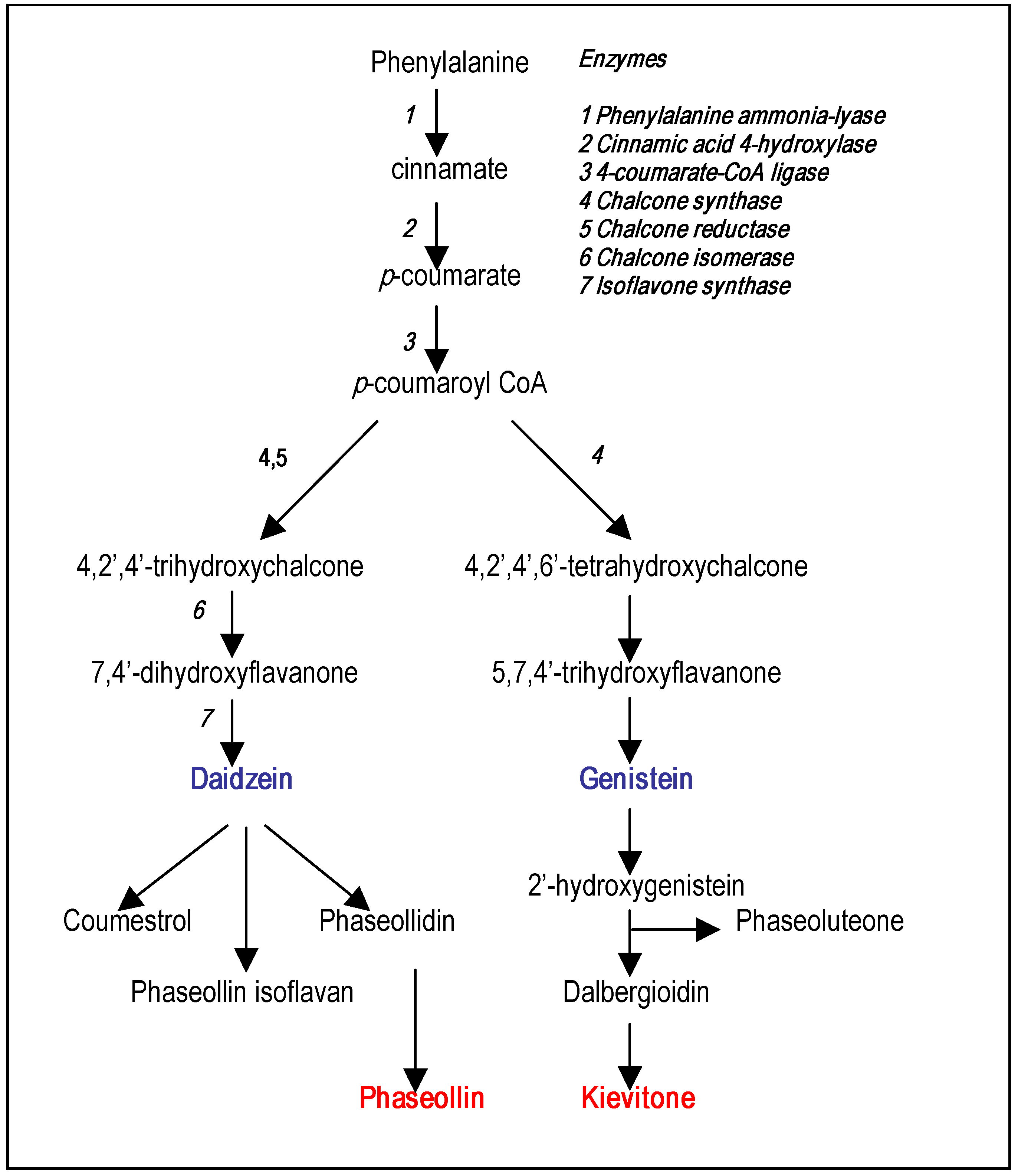

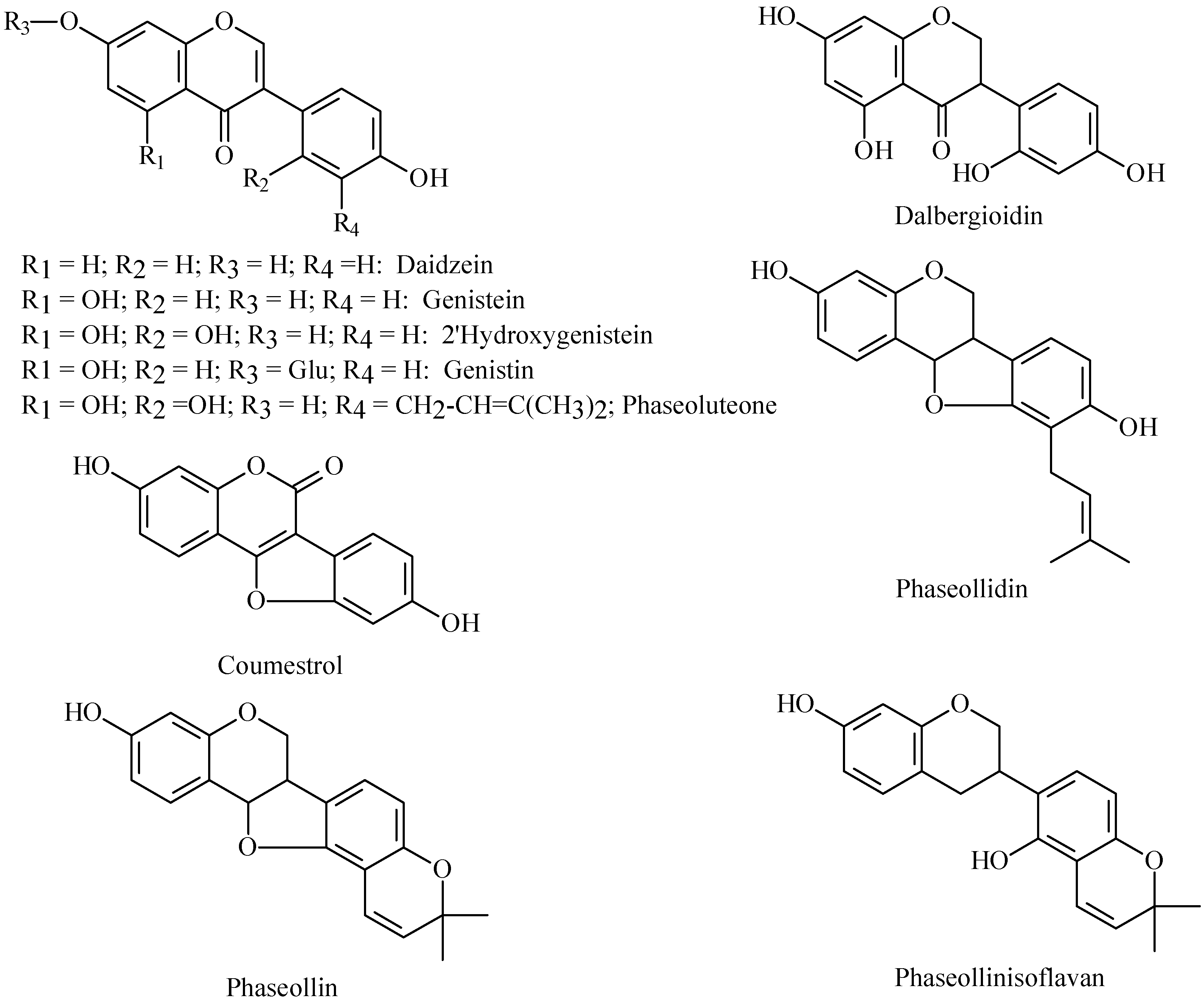

Phytoalexin structures

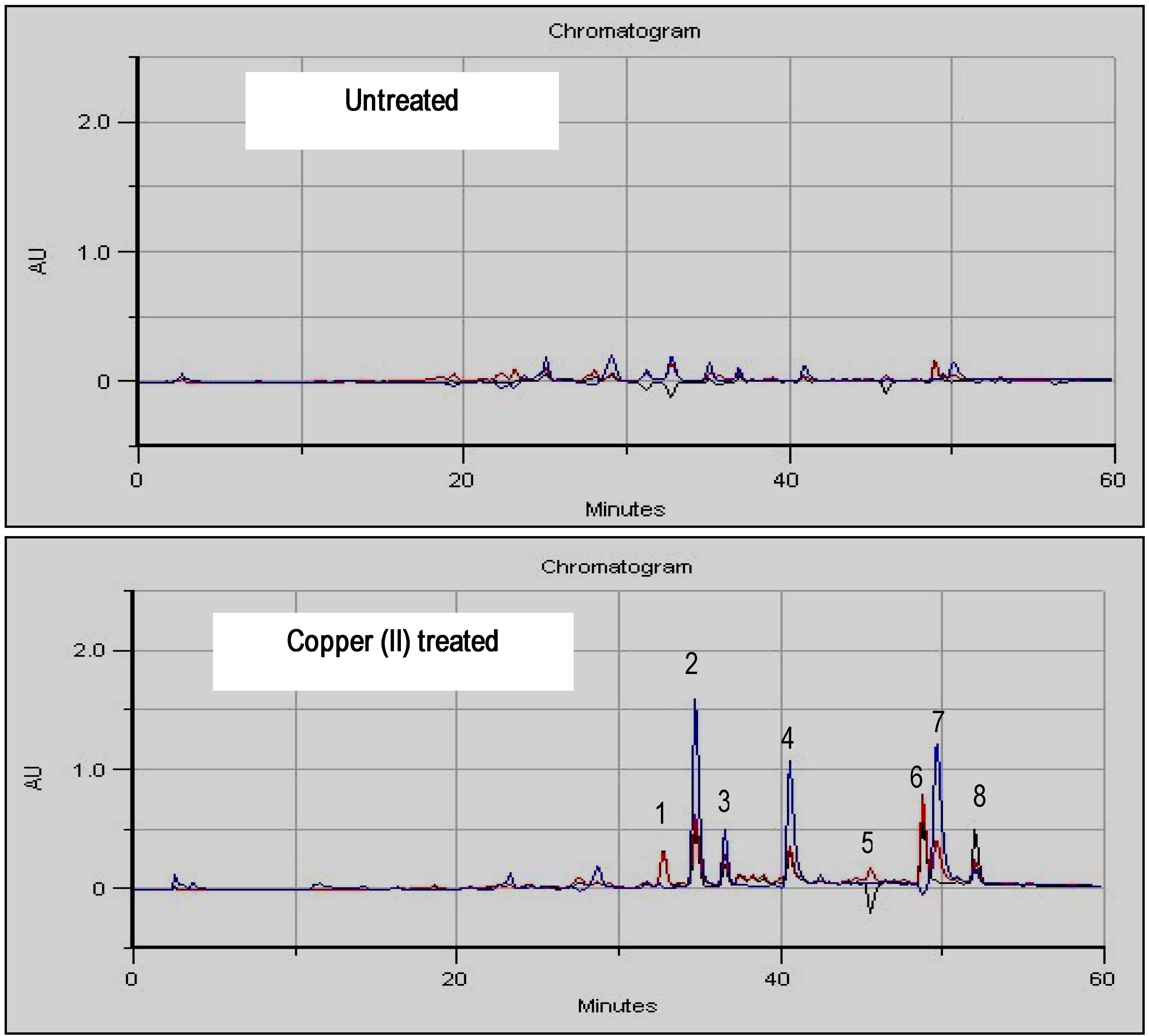

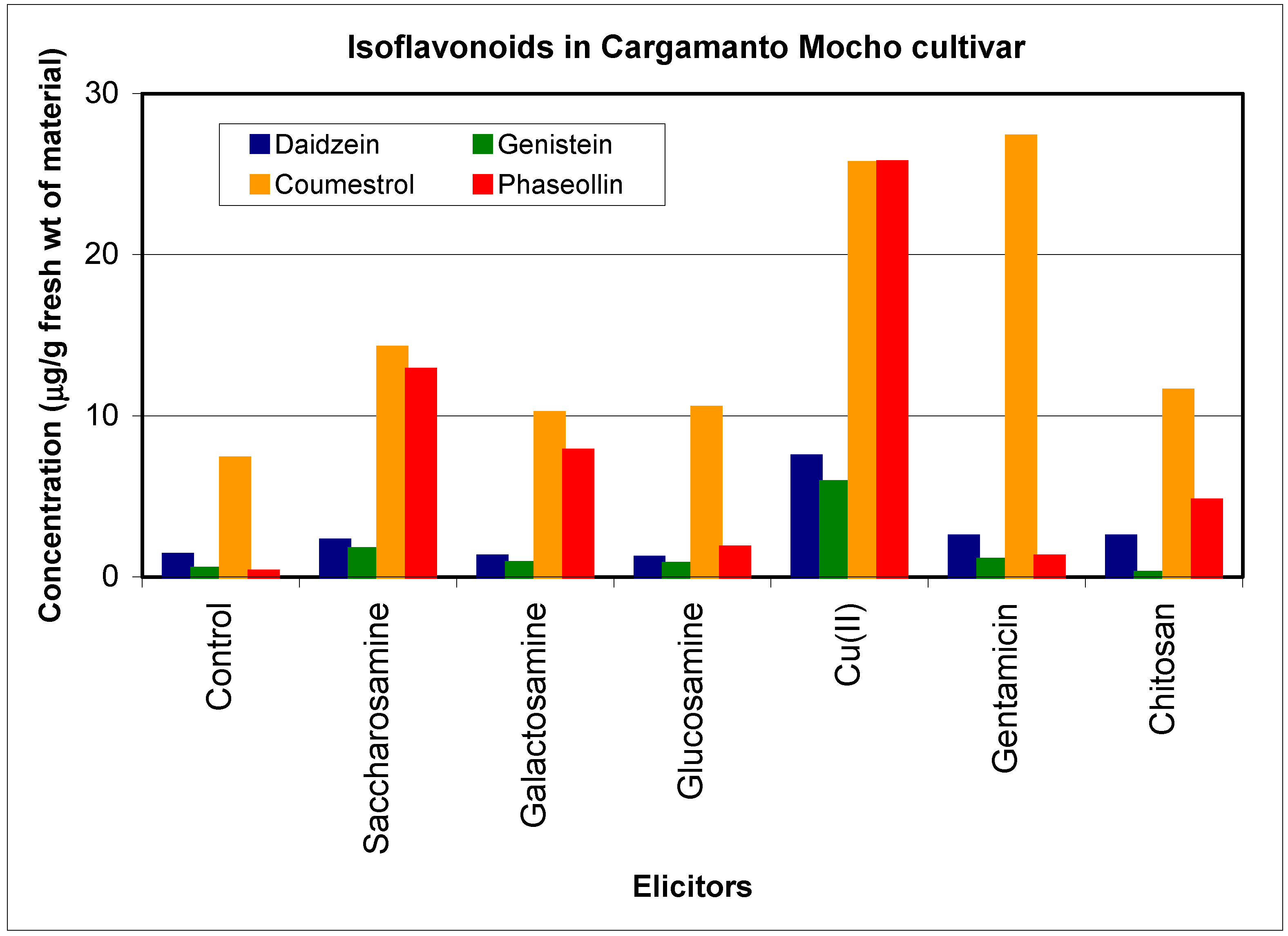

Inductor selection

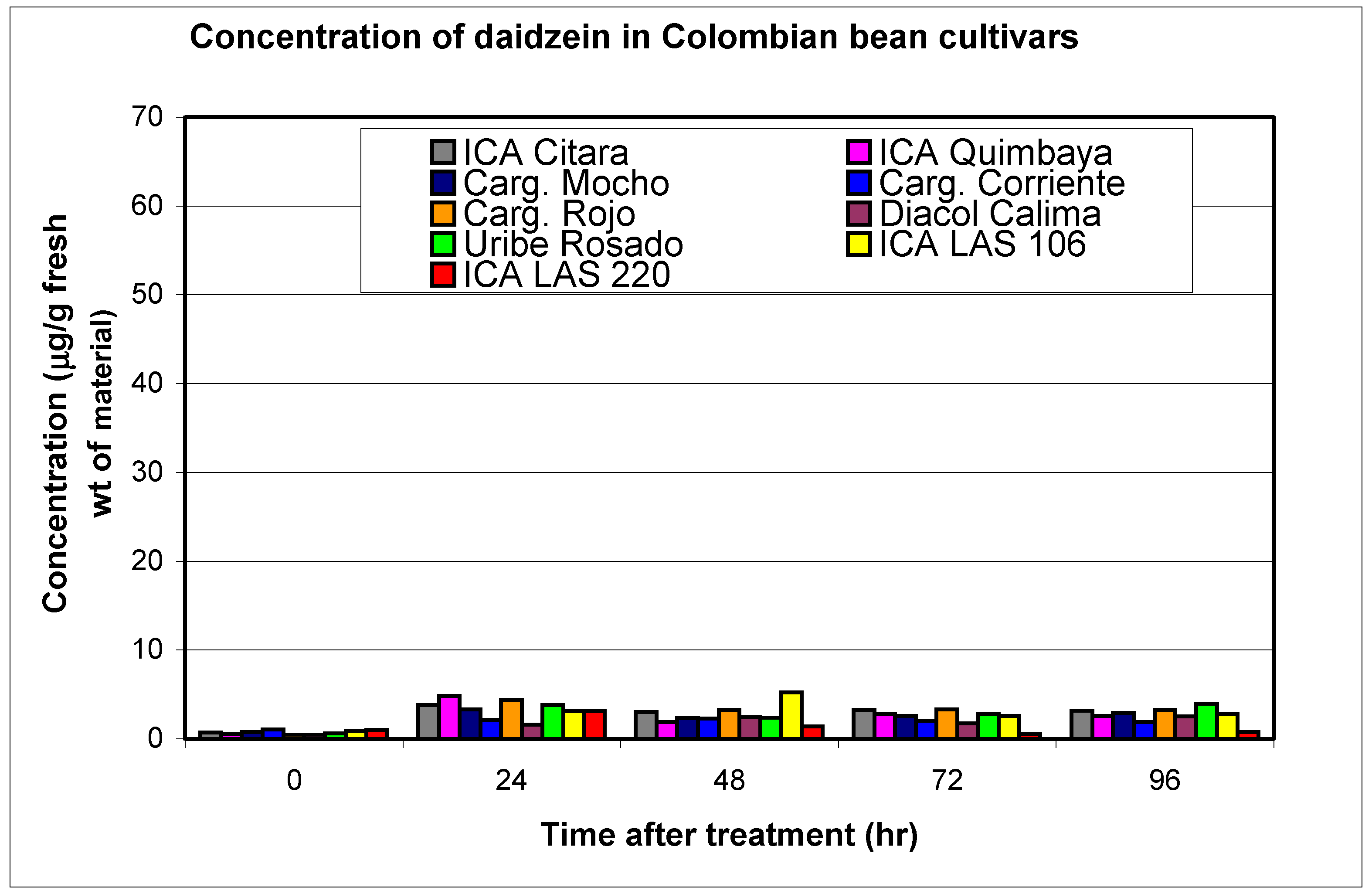

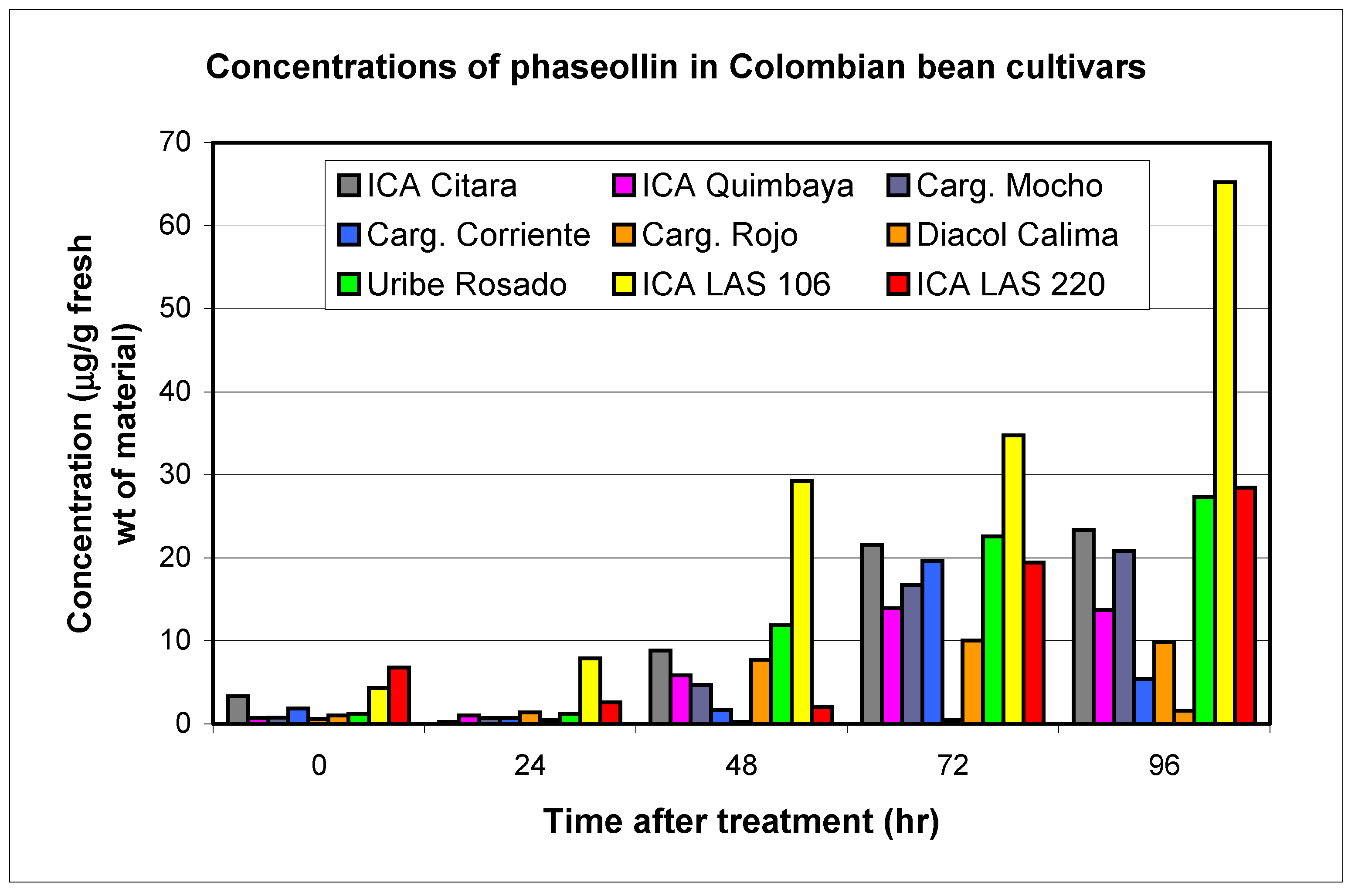

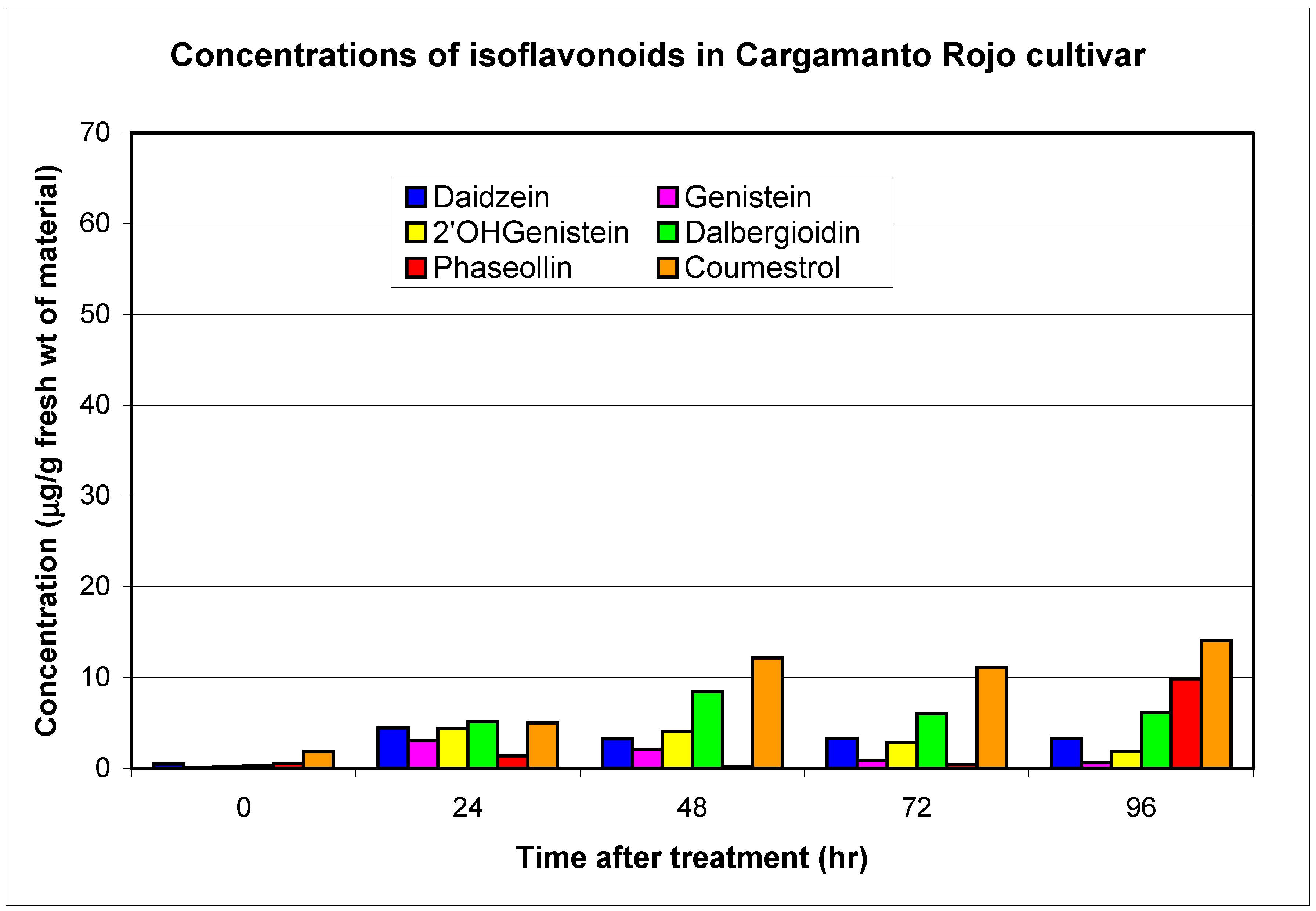

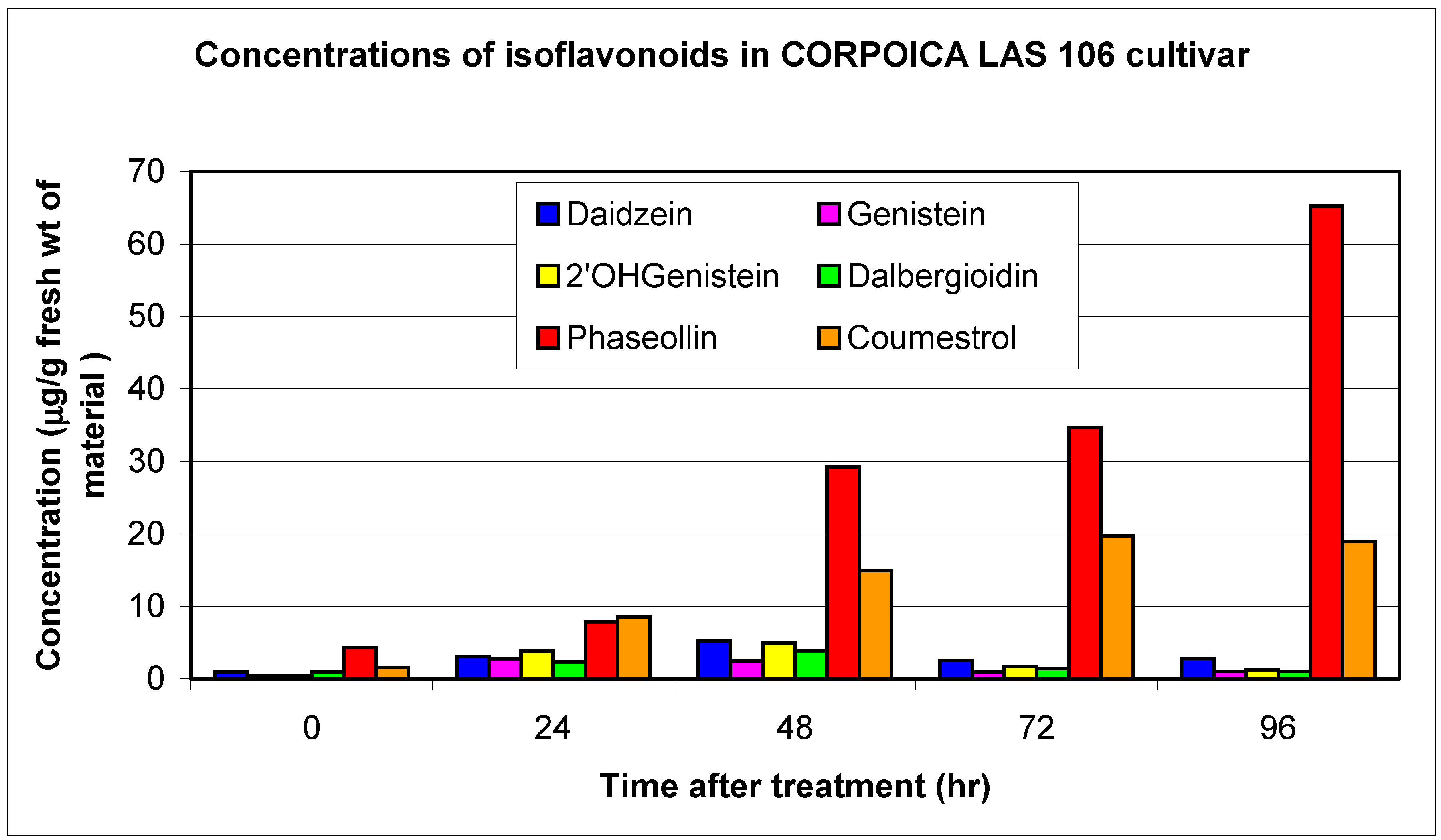

Resistant and susceptible cultivars

| Cultivars | Phytopatdology | Genistein | 2'-hydroxy-genistein | Dalbergioidin | Total 24 Hours | Daidzein | Phaseollin | Coumestrol | ||||||

| Time after treatment (hours) | ||||||||||||||

| 0 | 24 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 96 | 0 | 96 | |||

| Relative maximum concentration (μg/g of fresh weight) | ||||||||||||||

| ICA Calima (CAL) | S | 0.1 | 2.5 | 0.1 | 3.6 | 0.3 | 4.9 | 11.0 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 41.3 |

| Cargamanto Rojo (CRO) | S | 0.1 | 3.1 | 0.2 | 4.4 | 0.4 | 11.2 | 18.7 | 0.5 | 4.4 | 0.6 | 9.8 | 1.9 | 14.0 |

| Cargamanto Mocho (CMO) | S | 0.1 | 2.0 | 0.2 | 3.7 | 0.2 | 3.7 | 9.4 | 0.8 | 3.4 | 0.7 | 20.8 | 1.6 | 14.5 |

| Cargamanto Corriente (CCO) | S | 0.2 | 3.8 | 0.3 | 6.7 | 0.4 | 7.7 | 18.2 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 5.4 | 1.9 | 7.8 |

| Uribe Rosado (URO) | S | 0.1 | 2.2 | 0.2 | 5.8 | 0.1 | 5.1 | 13.1 | 0.6 | 3.8 | 1.2 | 27.4 | 2.1 | 26.7 |

| TOTALS | 0.6 | 13.6 | 1.0 | 24.2 | 1.2 | 32.6 | 3.5 | 15.4 | 5.3 | 65.0 | 8.8 | 104.3 | ||

| ICA Citará (ICI) | T | 0.2 | 3.4 | 0.2 | 4.6 | 0.5 | 6.0 | 14.0 | 0.8 | 3.9 | 3.3 | 23.3 | 5.1 | 22.8 |

| Quimbaya (IQU) | R | 0.1 | 3.0 | 0.1 | 5.5 | 0.5 | 5.9 | 14.4 | 0.6 | 4.9 | 0.7 | 14.0 | 1.9 | 17.8 |

| LAS 106 | R | 0.4 | 2.8 | 0.5 | 3.9 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 11.1 | 1.0 | 3.1 | 4.3 | 65.2 | 1.6 | 19.8 |

| LAS 220 | R | 0.6 | 4.2 | 0.9 | 7.8 | 0.4 | 11.8 | 23.2 | 1.0 | 3.2 | 6.8 | 28.5 | 4.8 | 26.9 |

| TOTALS | 1.2 | 13.4 | 1.7 | 21.8 | 2.4 | 26.1 | 3.4 | 15.1 | 15.1 | 131.0 | 13.4 | 87.3 | ||

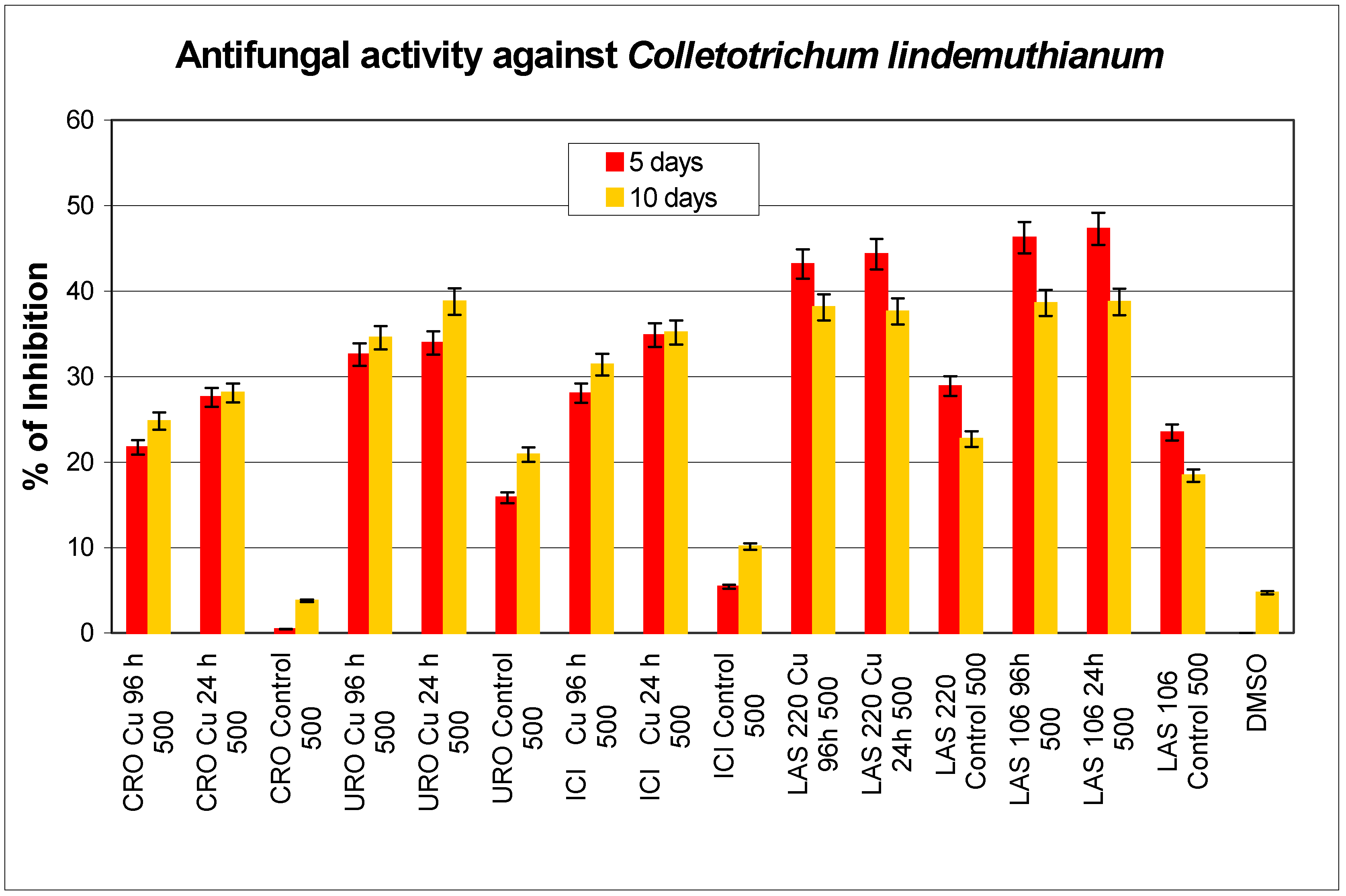

Antibiotic activity

Conclusions

- By development of HPLC methodologies to select clones of resistant beans according to the plant’s behavior of toward elicitors and phytoalexin levels.

- By control of the enzymes and genes involved in the phytoalexin production with abiotic elicitors to induce production of antibiotic phytoalexin at a specific time.

Experimental

General

Plant material

Induction of phytoalexins and elicitor selection

Isolation and identification of phytoalexins

Time course study of phytoalexin production

Antimicrobial assays

Phytoalexin characterization

Acknowledgments

References

- Hammerschmidt, R.; Schultz, J. Multiple defenses and signals in plant defense against pathogens and herbivores. Recent Adv. Phytochem. 1996, 30, 121–154. [Google Scholar]

- Grayer, R. J.; Kokubun, T. Plant-fungal interactions: the search for phytoalexins and other antifungal compounds from higher plants. Phytochemistry 2001, 56, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harborne, J.B. The comparative biochemistry of phytoalexin induction in plants. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 1999, 27, 335–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.Z.; Dixon, R. Genetic manipulation of isoflavone 7-O-methyltransferase enhances biosynthesis of 4´-O-methylated isoflavonoid phytoalexins and disease resistance in alfalfa. Plant Cell 2000, 12, 1689–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, V.M.; Overton, J.; Grayer, R.J.; Harborne, J.B. Difference in phytoalexin responce among rice cultivars of different resistance to blast. Phytochemistry 1997, 44, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otalvaro, F.; Echeverri, F.; Quiñones, W.; Torres, F.; Schneider, B. Correlation between phenylphenalenone phytoalexins and phytopathological properties in Musa and role of a dihydrophenylphenalene triol. Molecules 2002, 7, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glazebrook, J.; Rogers, E.E.; Ausubel, F.M. Isolation of Arabidopsis mutants with enhanced disease susceptibility by direct screening. Genetics 1996, 143, 973–982. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward, M. Phaseollin formation and metabolism in Phaseolus vulgaris. Phytochemistry 1980, 19, 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, C.; Watson, D. Phytoalexins. Nat. Prod. Rep. 1985, 2, 427–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essenberg, M. Prospects for strengthening plant defenses through phytoalexin engineering. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2001, 59, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Mufti, S.; Jenner, M. R. Synthesis of 1’,6,6’-triamino-1’,6,6’-trideoxy derivatives of sucrose. Carbohydr. Research 1973, 30, 183–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarosz, S.; Mach, M. Synthesis of sucrose derivatives modified at the terminal carbon atoms. Pol. J. Chem. 1999, 73, 981–988. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward, M. Phaseoluteone and other 5-hydroxyisoflavonoids from Phaseolus vulgaris L. Life Sci. 1979, 2, 680–682. [Google Scholar]

- Linding, C.; Benrey, B.; Espinosa, F. Phytoalexins, resistance traits, and domestication status in Phaseolus coccineus and Phaseolus lunatus. J. Chem. Ecol. 1997, 23, 1997–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakora, F.; Phillips, D. Diverse functions of isoflavonoids in legume transcend anti-microbial definitions of phytoalexins. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 1996, 49, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.A.; Banks, S.W. Biosynthesis, elicitation and biological activity of isoflavonoid phytoalexins. Phytochemistry 1986, 25, 979–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiva, N. An introduction to the biosynthesis of chemicals used in plant-microbe communication. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2000, 19, 131–143. [Google Scholar]

- Afzal, M.; Al-Oriquat, G. Biosynthesis of isoflavonoids and related phytoalexins. Heterocycles 1982, 19, 1295–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fader, M. Isoflavone biosynthetic enzymes. U.S. Patent 6,054,636, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, R.A.; Paiva, N.L.; Oommen, A. Isoflavone reductase promoter. U.S. Patent 5,750,399, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Sample Availability: Samples are available from the authors.

© 2002 by MDPI (http://www.mdpi.org). Reproduction is permitted for noncommercial purposes.

Share and Cite

Durango, D.; Quiñones, W.; Torres, F.; Rosero, Y.; Gil, J.; Echeverri, F. Phytoalexin Accumulation in Colombian Bean Varieties and Aminosugars as Elicitors. Molecules 2002, 7, 817-832. https://doi.org/10.3390/71100817

Durango D, Quiñones W, Torres F, Rosero Y, Gil J, Echeverri F. Phytoalexin Accumulation in Colombian Bean Varieties and Aminosugars as Elicitors. Molecules. 2002; 7(11):817-832. https://doi.org/10.3390/71100817

Chicago/Turabian StyleDurango, Diego, Winston Quiñones, Fernando Torres, Yoni Rosero, Jesús Gil, and Fernando Echeverri. 2002. "Phytoalexin Accumulation in Colombian Bean Varieties and Aminosugars as Elicitors" Molecules 7, no. 11: 817-832. https://doi.org/10.3390/71100817