4. Microbial-Catalyzed Biotransformation of Natural Tetracyclic Triterpenoids

Cycloastragenol (

25), or (20

R,24

S)-3β,6α,16β,25-tetrahydroxy-20,24-epoxycycloartane (

Figure 10), is the genuine sapogenin of astragaloside IV, a major bioactive constituent of Astragalus plants. Astragaloside IV exhibits various pharmacological properties, such as anti-inflammatory, anti-viral, anti-aging and anti-oxidant. It could retard the onset of cellular aging by progressing telomerase activity, up-regulate the immune system by inducing IL-2 release, and elevate the antiviral function of human CD8+ T lymphocytes. Compound

25 has been considered as a promising new generation of anti-aging agent [

26].

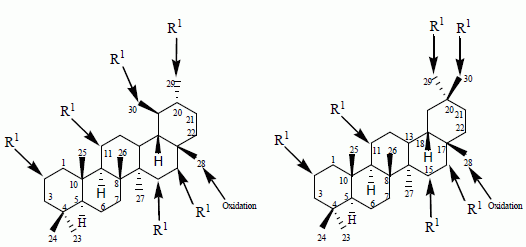

The biocatalysis of

25 with two fungal strains,

Cunninghamella blakesleeana NRRL 1369 and

Glomerella fusarioides ATCC 9552, and the bacterium

Mycobacterium sp. NRRL 3805 was investigated by Kuban

et al. [

24,

25]. These strains efficiently transformed

25 into hydroxylated metabolites along with products formed by cyclization, dehydrogenation and Baeyer–Villiger oxidation resulting in a ring cleavage (

Figure 10) [

25].

C. blakesleeana efficiently transformed

25 into a complicated rearrangement product,

i.e., ring cleavage and methyl group migration of

25, (20

R,24

S)-3β,6α,6β,19,25-pentahydroxy-ranunculan-9(10)-ene (

26) (

Figure 10) [

24]. With same microorganism, the substrate cycloastragenol (

25) underwent several regioselective hydroxylatedproducts, (20

R,24

S)-3β,6α,16β,19,25-pentahydroxy-ranunculan-9(10)-ene (

26), (20

R,24

S)-epoxy-1α-3β,6α,16β,25-pentahydroxycycloartane (

27), (20

R,24

S)-epoxy-3β,6α,11β,16β,25-pentahydroxycycloartane (

28), (20

R,24

S)-16β,24;20,24-diepoxy-3β,6α,12β,25-tetrahydroxycycloartane (

29), (20

R,24

S)-epoxy-3β,6α,12β-16β,25-pentahydroxycycloartane (

30) and an unsaturated product, (20

R,24

S)-epoxy-3β,6α,16β,25-tetrahydroxycycloarta-11(12)-ene (

31). Ring cleavage product, 3,4-seco cycloastragenol (

32) and (20

R,24

S)-epoxy-3β,6α,11β,16β,25-pentahydroxycycloartane (

28) was isolated from the fungus

G. fusarioides.The

Mycobacterium sp. NRRL 3805 transformed

25 into oxidation product,

33 in 24 h. These biotransformation reactions are shown in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 [

25].

Ye

et al. reported the biotransformation of

25 by

Cunninghamella elegans AS 3.1207,

Syncephalastrum racemosum AS 3.264 and

Doratomyces stemonitis AS 3.1411 [

26]. Biocatalytic fermentations of

25 with

C. elegans AS 3.1207 for 6 days afforded several regioselective hydroxylated metabolites presented in

Figure 12, (20

R,24

S)-2α,3β,6α,16β,25-pentahydroxy-20,24-epoxycycloartane (

34), (20

R,24

S)-3β,6α,12α,16β,25-pentahydroxy-20,24-epoxy-cycloartane (

35), (20

R,24

S)-3β,6α,16β,25,28-pentahydroxy-20,24-epoxy-cycloartane (

36), (20

R,24

S)-3β,6α,16β,25,29-pentahydroxy-20, 24-epoxy-cycloartane (

37), (20

R,24

S)-3β,6α,16β,25-tetrahydroxy-20,24-epoxy-cycloartan-28-carbaldehyde (

38), (20

R,24

R)-3β,6α,25,28-tetrahydroxy-16β,24:20,24-diepoxy-cycloartane (

39) and (20

R,24

S)-3β,6α,16β,19,25-pentahydroxy-ranunculan-9(10)-ene (

26) [

26].

Figure 10.

Biotransformation of cycloastragenol (25) by Cunninghamella blakesleeana NRRL 1369.

Figure 10.

Biotransformation of cycloastragenol (25) by Cunninghamella blakesleeana NRRL 1369.

Figure 11.

Biocatalytic reactions of Glomerella fusarioides ATCC 9552 and Mycobacterium sp. NRRL 3805 on cycloastragenol (25).

Figure 11.

Biocatalytic reactions of Glomerella fusarioides ATCC 9552 and Mycobacterium sp. NRRL 3805 on cycloastragenol (25).

Figure 12.

Biocatalytic reactions of Cunninghamella elegans AS 3.1207 on cycloastragenol (25).

Figure 12.

Biocatalytic reactions of Cunninghamella elegans AS 3.1207 on cycloastragenol (25).

Bioconversion of

25 by

S. racemosum AS 3.264 yielded (20

R,24

S)-3β,6α,16β,19,25-pentahydroxy-ranunculan-9(10)-ene (

26), (20

R,24

S)-3β,6α,12α,16β,25-pentahydroxy-20,24-epoxy-cycloartane (

35), (20

R,24

S)-3β,6α,16β,25-tetrahydroxy-20,24-epoxy-cycloartan-11-one (

40), (20

R,24

S)-3β,6α,16β,25-tetrahydroxy-20,24-epoxy-cycloartan-11(12)-ene (

41), (20

R,24

S)-3β,6α,16β,25-tetrahydroxy-19-butoxy-ranunculan-9(10)-ene (

42), (20

R,24

S)-3β,6α,16β,25-tetrahydroxy-19-isopentenyloxyranunculan-9(10)-ene (

43), (20

R,24

S)-3β,6α,16β,25-tetrahydroxy-19-acetoxy-ranunculan-9(10)-ene (

44) and ring expansion metabolite, neoastragenol or (20

R,24

S)-3β,6α,16β,25-tetrahydroxy-20,24-epoxy-9(10)a-homo-19-nor-cycloartane (

45) (

Figure 13).

D. stemonitis AS 3.1411 transformed

25 to two carbonylated metabolites, (20

R,24

S)-6α,16β,25-trihydroxy-20,24-epoxy-cycloartan-3-one (

46), (20

R,24

S)-6α,16β,25,30-tetrahydroxy-20,24-epoxy-cycloartan-3-one (

47) and

26. These transformations are shown in

Figure 14 [

26].

Figure 13.

Biotransformation of Syncephalastrum racemosum AS 3.264 on cycloastragenol (25).

Figure 13.

Biotransformation of Syncephalastrum racemosum AS 3.264 on cycloastragenol (25).

Figure 14.

Biotransformation of Doratomyces stemonitis AS 3.1411 on cycloastragenol (25).

Figure 14.

Biotransformation of Doratomyces stemonitis AS 3.1411 on cycloastragenol (25).

The tetratriterpenoid 20(

S)-Protopanaxadiol (

48), a glycone of ginsenosides from the Chinese ginseng (

Panax ginseng C.A. Mey, Araliaceae) exhibits powerful pleiotropic anti-cancer effects in several cancer cell lines including the inhibition of metastasis. Furthermore, compound

48 could induce apoptosis through mitochondria mediated apoptotic pathway in Caco-2, U937, THP-1, and SMMC7721 cancer cells [

27]. The fungal tansformation of

48 was reported by Li

et al. Fermentation of

48 with

Mucor spinosus AS 3.3450 for 5 days yielded eight regioselective hydroxylated metabolites (

49–

56), 12-oxo-15α,27-dihydroxyl-20(

S)-protopanaxadiol (

49), 12-oxo-7β,11α,28-trihydroxyl-20(

S)-protopanaxadiol (

50), 12-oxo-7β,28-dihydroxyl-20(

S)-protopanaxadiol (

51), 12-oxo-15α, 29-dihydroxyl-20(

S)-protopanaxadiol (

52), 12-oxo-7β,15α-dihydroxyl-20(

S)-protopanaxadiol (

53), 12-oxo-7β,11β-dihydroxyl-20(

S)-protopanaxadiol (

54), 12-oxo-15α-hydroxyl-20(

S)-protopanaxadiol (

55), and 12-oxo-7β-hydroxyl-20(

S)-protopanaxadiol (

56) (

Figure 15). Incubation of

48 with

Aspergillus niger AS 3.1858 afforded seven additional hydroxylated metabolites (

57–63), 26-hydroxyl-20(

S)-protopanaxadiol (

57), 23,24-en-25-hydroxyl-20(

S)-protopanaxadiol (

58), 25,26-en-20(

S)-protopanaxadiol (

59), (

E)-20,22-en-25-hydroxyl-20(

S)- protopanaxadiol (

60), 25,26-en-24(

R)-hydroxyl-20(

S)-protopanaxadiol (

61), 25,26-en-24(

S)-hydroxyl-20(

S)-protopanaxadiol (

62) and 23,24-en-25-ethoxyl-20(

S)-protopanaxadiol (

63) [

28]. These biotransformation reactions are described in

Figure 16.

The bacterium

Bacillus megaterium metabolized the triterpenoid dipterocarpol (

64) to 7β-hydroxydipterocarpol (

65) and 7β,11α-dihydroxydipterocarpol (

66) in 16 h (

Figure 17). The Dipterocarpol (

64) and the dihydroxylated product

66 did not displayed cytotoxic activity with HeLa and COS-1 cells while 7β-hydroxylated product

65 exhibited cytotoxicity on both the cell lines [

29].

Figure 15.

Biotransformation of Mucor spinosus AS 3.3450 on 20(S)-protopanaxadiol (48).

Figure 15.

Biotransformation of Mucor spinosus AS 3.3450 on 20(S)-protopanaxadiol (48).

Figure 16.

Biotransformations of Aspergillus niger AS 3.1858 on 20(S)-protopanaxadiol (48).

Figure 16.

Biotransformations of Aspergillus niger AS 3.1858 on 20(S)-protopanaxadiol (48).

Figure 17.

Biotransformation of dipterocarpol (64) with Bacillus megaterium ATCC 13368.

Figure 17.

Biotransformation of dipterocarpol (64) with Bacillus megaterium ATCC 13368.

Schisandra propinqua var.

sinensis, popularly known as “tie-gu-san” produced by Schisandraceae family in the Shennongjia district of mainland China, is used as folk medicine for the treatment of arthritis, traumatic injury, gastralgia, angeitis, and other related diseases. Nigranoic acid (3,4-secocycloarta- 4(28),24(

Z)-diene-3,26-dioic acid,

67) is the first member of class 3,4-secocycloartane triterpenoid produced by

Schisandra propinqua, that has been reported to possess a variety of biological activities, including cytotoxic activity toward leukemia and Hela cells, and inhibition of expression of HIV reverse transcriptase and polymerase [

31]. Dong

et al. studied the microbiological transformation of

67 by the freshwater fungus

Dictyosporium heptasporum YMF1.01213. The organism metabolized

67 into novel nine-membered lactone ring 3,4-secocycloartane triterpenoid derivatives, 3,4-secocycloarta-4(28),17(20),24(

Z)-triene-7β-hydroxy-16β,26-lactone-3-oic acid (

68) and 3,4-secocycloarta-4(28),17(20)(

Z),24(

Z)-triene-7β-hydroxy-16β-methoxy-3,26-dioic acid (

69) (

Figure 18) [

30].

Dong

et al. reported the bioconversion of

67 by cultures of

Trichoderma sp. JY-1. The fungus yielded 15α,16α-dihydroxy-3,4-secocyloarta-4(28),17(20),17(

E),24(

E)-triene-3,26-dioic acid (

70) and 16α,20α-dihydroxy-18 (13→17β) abeo-3,4-secocyloarta-4 (28),12(13),24(

Z)-triene-3,26-dioic acid (

71). Substrate

67 and its transformed products

70 and

71 displayed weak anti-HIV activity with EC

50 values of 10.5, 8.8 and 7.6 mg/mL, and therapeutic index values (CC

50/EC

50) of 8.48, 9.12 and 10.1, respectively (

Figure 19) [

31].

Figure 18.

Microbiological transformation of the triterpene nigranoic acid (67) by the freshwater fungus Dictyosporium heptasporum.

Figure 18.

Microbiological transformation of the triterpene nigranoic acid (67) by the freshwater fungus Dictyosporium heptasporum.

Figure 19.

Metabolism of 67 by Trichoderma sp. JY-1 culture.

Figure 19.

Metabolism of 67 by Trichoderma sp. JY-1 culture.

5. Microbial Transformation of Natural and Semi-Synthetic Pentacyclic Triterpenoids

Pentacyclic triterpenoids (

3–

4) are widely distributed in many medicinal plants, such as birch bark (betulin,

153), plane bark (betulinic acid,

154), olive leaves, olive pomace, mistletoe sprouts and clove flowers (oleanolic acid,

72), and apple pomace (ursolic acids,

114). Compounds belonging to this group such as lupane (lupeol, betulin, betulinic acid), oleanane (

72 and maslinic acid (

73), erythrodiol, β-amyrin), and ursane (

114, uvaol, α-amyrin) display various pharmacological effects. These triterpenoids are ideal and potential candidates for designing lead compounds for the development of new bioactive agents [

32].

Olean-type pentacyclic triterpenes (OPTs) are plant-derived natural products, abundantly found in many medicinal herbs. They display a remarkable spectrum of biological activities, such as antimalarial, anti-tumor, anti-HIV, anti-microbial, anti-diabetic, and anti-inflammatory activities [

32]. The microbial-catalyzed modification of olean-type pentacyclic triterpenes mainly resulted in the substitution of hydroxyl or carbonyl groups to the methyl or methenyl carbons of the skeleton and the formation of corresponding glycosides [

32]. The presence of such functional moieties, especially at C-3, C-28, and C-30, seems to contribute to the biological activities of pentacyclic triterpenoids [

17,

35,

36].

Oleanolic acid (3β-hydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid,

72) is a natural pentacyclic triterpenoid compounds widely present in the form of free acid or aglycone of triterpenoid saponins. It is usually found in high concentrations in olive-pomace oil [

32]. Some oleanolic acids have been reported to be antimalarial, antitumor, hepatoprotective, anti-HIV, and skin protective. They seem to possess α-glucosidase inhibitory activity.

Figure 20.

Microbial transformation of oleanolic acid (72) by Furarium lini NRRL-68751 and Colletotrichum lini AS3.4486.

Figure 20.

Microbial transformation of oleanolic acid (72) by Furarium lini NRRL-68751 and Colletotrichum lini AS3.4486.

Several biotransformations of oleanolic acid (

72) with different microorganisms have been reported so far. Choudhary

et al. investigated the metabolism of oleanolic acid (

72) with

Fusarium lini NRRL-68751 and reported the production of two oxidative metabolites, maslinic acid (2α,3β-dihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid,

73) and 2α,3β,11β-trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid (

74) (

Figure 20). These metabolites show potent inhibition of α-glucosidase activity. Hua

et al. reported the metabolism of

72 with

Colletotrichum lini AS3.4486 which resulted in one polar metabolite, 15α-hydroxyl-oleanolic acid (

75) (

Figure 20) [

17,

33].

Liu

et al. reported microbial transformation of

72 with

Alternaria longipes and

Penicillium adametzi. The fungus

Alternaria longipes converted

72 to six different regioselective hydroxylated products, 2α,3α,19α-trihydroxy-ursolic acid-28-

O-β-d-glucopyranoside (

76), 2α,3β,19α-trihydroxy-ursolic acid-28-

O-β-d-glucopyranoside (

77), oleanolic acid 28-

O-β-d-glucopyranosyl ester (

78), oleanolic acid-3-

O-β-d-glucopyranoside (

79), 3-

O-(β-d-glucopyranosyl)-oleanolic acid-28-

O-β-d-glucopyranoside (

80), 2α,3β,19α-trihydroxy-oleanolic acid-28-

O-β-d-glucopyranoside (

81), while cultures of

Penicillium adametzi transformed the

72 to 21β-hydroxyl oleanolic acid (

82), 7α,21β-dihydroxyl oleanolic acid (

83) and 21β-hydroxyl oleanolic acid-28-

O-β-d-glucopyranoside (

84). These fermentation reactions are presented in

Figure 21 and

Figure 22. Compounds

79 and

82–

84 exhibited stronger cytotoxic activities against Hela cell lines than the substrate

72 [

34].

Figure 21.

Microbial transformation of oleanolic acid (72) by Alternaria longipes.

Figure 21.

Microbial transformation of oleanolic acid (72) by Alternaria longipes.

Figure 22.

Microbial transformation of oleanolic acid (72) by Penicillium adametzi.

Figure 22.

Microbial transformation of oleanolic acid (72) by Penicillium adametzi.

Chapel

et al. reported the microbial transformation of

72 with the filamentous fungus,

Mucor rouxii. Fermentation process yielded four regioselective derivatives,

83, 7

β-hydroxy-3-oxo-olean-12-en-28-oic acid (

85), 21

β-hydroxy-3-oxo-olean-12-en-28-oic acid (

86) and 7

β,21

β-dihydroxy-3-oxo-olean-12-en-28-oic acid (

87) (

Figure 23). Compound

86 displayed the potent activity against

Porphyromonas gingivalis [

35].

Martinez

et al. investigated biotransformation of

72 with

Rhizomucor miehei CECT 2749 and reported the production of a mixture of polar metabolites, 3β,30-dihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid (

88), (also called queretaroic acid), 3β,7β,30-trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid (

89), (also called canthic acid) and 1β,3β,30-trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid (

90) (

Figure 24) [

36]. On the other hand, Gong

et al. reported metabolism of

72 with

Trichothecium roseum and showed the production of two hydroxylated metabolites, 15α-hydroxy-3-oxo-olean-12-en-28-oic acid (

91) and 7β,15α-dihydroxy-3-oxo-olean-12-en-28-oic acid (

92) (

Figure 25) [

37].

Figure 23.

Microbial transformation of oleanolic acid (72) by Mucor rouxii.

Figure 23.

Microbial transformation of oleanolic acid (72) by Mucor rouxii.

Figure 24.

Metabolites isolated from the incubation of oleanolic acid (72) with Rhizomucor miehei.

Figure 24.

Metabolites isolated from the incubation of oleanolic acid (72) with Rhizomucor miehei.

Figure 25.

Metabolites isolated from the incubation of oleanolic acid (72) with Trichothecium roseum.

Figure 25.

Metabolites isolated from the incubation of oleanolic acid (72) with Trichothecium roseum.

Microbial transformation of

72 and three synthetic olean-type pentacyclic triterpenes, 3-oxo oleanolic acid (

93), 3-acetyl oleanolic acid (

94) and esculentoside A (

95) with

Streptomyces griseus ATCC 13273 and

Aspergillus ochraceus CICC 40330 was reported by Zhu

et al. (see

Figure 26,

Figure 27,

Figure 28,

Figure 29 and

Figure 30). These highly efficient and regioselective methyl oxidation and glycosylation provided an alternative approach to expand the structural diversity of OPTs [

38]. The two interesting reactions observed during fermentation of four synthetic pentacyclic triterpenoids (

3–

4) with

S. griseus ATCC 13273 and

A. ochraceus CICC 40330, are the the regio-selective oxidation of the methyl group on C-4 and C-20 and the formation of glycosyl ester of C-28 carboxyl group. Fermentation of

72 with

S. griseus ATCC 13273 yielded two more polar metabolites, serratagenic acid (

96) and 3β,24-dihydroxy-olean-12-en-28,29-dioic acid (

97). Incubation of

72 with

A. ochraceus CICC 40330 afforded another polar metabolite,

78 (

Figure 26) [

38].

Incubation of 3-oxo oleanolic acid (

93) with

S. griseus ATCC 13273 produced two polar metabolites, 3-oxo-olean-12-en-28,29-dioic acid (

98) and 24-hydroxy-3-oxo-olean-12-en-28,29-dioic acid (

99). On the other hand, incubation of

93 with

A. ochraceus CICC 40330 afforded a different polar metabolite 28-

O-β-

d-glucopyranosyl 3-oxo-olean-12-en-28-oate (

100) (

Figure 27). The subsequent metabolism of

94 has also been reported. The bacterium

S. griseus transformed

94 to two polar regioselective products,

96 and

97 (

Figure 28). Compound

78, 28-

O-β-

d-glucopyranosyl,3β-hydroxy-olean-12-en-28-oate was isolated from the culture of

A. ochraceus CICC 40330 (

Figure 28). Another substrate, esculentoside A (

95) when incubated with

S. griseus ATCC 13273 for 5 days yieled two less polar products, esculentoside B (

104) and phytolaccagenin (

105). Guo

et al. investigated the regioselective bioconversion of

93 using the fungus

Absidia glauca and reported the production of three novel hydroxylated metabolites, 1β-hydroxy-3-oxo-olean-11-en-28,13-lactone (

101), 1

β,11α-dihydroxy-3-oxo-olean-12-en-28-oic acid (

102), and 1β,11α,21β-trihydroxy-3-oxo-olean-12-en-28-oic acid (

103) (

Figure 29) [

39].

Figure 26.

Microbial transformation of oleanolic acid (72) by Streptomyces griseus ATCC 13273 and Aspergillus ochraceus CICC 40330.

Figure 26.

Microbial transformation of oleanolic acid (72) by Streptomyces griseus ATCC 13273 and Aspergillus ochraceus CICC 40330.

Figure 27.

Microbial transformation of 3-oxo oleanolic acid (93) by Streptomyces griseus ATCC 13273 and Aspergillus ochraceus CICC 40330.

Figure 27.

Microbial transformation of 3-oxo oleanolic acid (93) by Streptomyces griseus ATCC 13273 and Aspergillus ochraceus CICC 40330.

Figure 28.

Microbial transformation of 3-acetyl oleanolic acid (94) by Streptomyces griseus ATCC 13273 and Aspergillus ochraceus CICC 40330.

Figure 28.

Microbial transformation of 3-acetyl oleanolic acid (94) by Streptomyces griseus ATCC 13273 and Aspergillus ochraceus CICC 40330.

Figure 29.

Microbial transformation of 3-oxo oleanolic acid (93) by growing cultures of the fungus Absidia glauca.

Figure 29.

Microbial transformation of 3-oxo oleanolic acid (93) by growing cultures of the fungus Absidia glauca.

However, the incubation of

95 with

A. ochraceus CICC 40330 afforded only metabolite

104. Further metabolism of compound

104 with

S. griseus ATCC 13273 produced 2β,3β,23,29-tetrahydroxy-olean-12-ene-28,30-dioic acid 30-methyl ester (

106) and incubation of

105 with

A. ochraceus CICC 40330 resulted 28-

O-β-

d-glucopyranosyl phytolaccagenin (

107) (

Figure 30) [

38].

Figure 30.

Microbial transformation of 3-oxo esculentoside A (95) by Streptomyces griseus ATCC 13273 and Aspergillus ochraceus CICC 40330.

Figure 30.

Microbial transformation of 3-oxo esculentoside A (95) by Streptomyces griseus ATCC 13273 and Aspergillus ochraceus CICC 40330.

The pentacyclic triterpene maslinic acid (2α,3β-dihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid,

73) is a natural pentacyclic triterpenoid compounds which is present in abundant amount in the surface wax on the fruits and leaves of Olea europaea. It is also a byproduct of the solid waste obtained from olive oil production. This compound is also found in

Agastache rugosa,

Lagerstroemia speciosa, and

Geum japonicum. Maslinic acid (

73) has anti-HIV, anticancer, anti-diabetic, antioxidant and antiatherogenic activities. Martinez

et al. investigated the metabolism of maslinic acid (

73) with

Rhizomucor miehei and reported the production of an olean-11-en-28,13β-olide derivative, 2α,3β-dihydroxyolean-11-en-28,13β-olide (

108) and a hydroxylated product at C-30 position; 2α,3β,30-trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid (

109). These biotransformation reactions are shown in

Figure 31 [

36].

Feng

et al. investigated the bioconversion of

73 by

C. blakesleeana CGMCC 3.910 and demonstrated the formation of four derivatives, 2α,3β,7β-trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid (

110), 2α,3β,15α-trihydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid (

111), 2α,3β,7β,15α-tetrahydroxyolean-12-en-28-oic acid (

112) and 2α,3β,7β,13β-tetrahydroxyolean-11-en-28-oic acid (

113) (

Figure 32) [

40].

Figure 31.

Metabolites isolated from the incubation of maslinic acid (73) with Rhizomucor miehei.

Figure 31.

Metabolites isolated from the incubation of maslinic acid (73) with Rhizomucor miehei.

Figure 32.

Microbial transformation of maslinic acid (73) by Cunninghamella blakesleeana.

Figure 32.

Microbial transformation of maslinic acid (73) by Cunninghamella blakesleeana.

Ursolic acid (3β-hydroxy-urs-12-en-28-oic acid, UA,

114), a pentacyclic triterpene acid, exists abundantly in many medicinal plants including sage, rosemary, thyme and lavender [

1,

41,

42]. It displays a remarkable spectrum of biological activities, such as anti-inflammatory activity, anti-allergic activity, antibacterial activity, anti-mutagenicity, hepatoprotective activity, rantimalarial and anti-tumor activity. In addition, UA is also used to induce apoptosis in human liver cancer cell lines, to enhance the cellular immune system and pancreatic β-cell function and to inhibit invasion [

1,

41].

Biotransformation of

114 by the filamentous fungus

Syncephalastrum racemosum (Cohn) Schroter AS 3.264 was reported by Huang

et al. They reported the regioselective hydroxylation, carbonylation, and condensation reactions. Bioconversion of

114 by

S. racemosum afforded five metabolites, 3β,21β-dihydroxy-urs-11-en-28-oic acid-13-lactone (

115), 3β,7β,21β-trihydroxy-urs-11-en-28-oic acid-13-lactone (

116), 1β,3β-dihydroxy-urs-12-en-21-one-28-oic acid (

117), 1β,3β,21β-trihydroxy-urs-12-en-28-oic acid (

118) and 11,26-epoxy-3β,21β-dihydroxyurs-12-en-28-oic acid (

119) (

Figure 33). Compound

117 showed moderate PTP1B inhibitory activity [

41].

Fu

et al. conducted microbial transformation of

114 with filamentous fungus

Syncephalastrum racemosum CGMCC 3.2500 (see

Figure 34) and showed the formation of five polar metabolites

115,

116,

117,

118 and 3β,7β,21β-trihydroxy-urs-12-en-28-oic acid (

120). Metabolites

118 and

120 exhibited anti-HCV activity [

42].

Figure 33.

Fermentation of ursolic acid (114) with Syncephalastrum racemosum (Cohn) Schroter AS 3.264.

Figure 33.

Fermentation of ursolic acid (114) with Syncephalastrum racemosum (Cohn) Schroter AS 3.264.

Figure 34.

Biotransformation of ursolic acid (114) with Syncephalastrum racemosum CGMCC 3.2500.

Figure 34.

Biotransformation of ursolic acid (114) with Syncephalastrum racemosum CGMCC 3.2500.

Endophytic microorganisms are bacterial or fungal organisms which colonize in the healthy plant tissue inter-and/or intracellularly without causing any apparent symptoms of disease. Endophytic microorganisms can produce bioactive natural substances, such as paclitaxel, podophyllotoxin

etc. [

43]

. Endophytic fungi extensively metabolized 2-hydroxy-1,4-benzoxazin-3(2

H)-one (HBOA) and biotransformed it to less toxic metabolites probable by their oxidase and reductases. Thus, endophytes attracted more and more attention not only for producing many novel substances but also to biotransform the natural products. Endophytic fungus,

Umbelopsis isabellina, isolated from medicinal plant

Huperzia serrata, was utilized to transform

114, into three regioselective products, 3β-hydroxy-urs-11-en-28,13-lactone (

121), 1β,3β-dihydroxy-urs-11-en-28,13-lactone (

122) and 3β,7β -dihydroxy-urs-11-en-28, 13-lactone (

123) (

Figure 35) [

44].

Figure 35.

Biotransformation of 114 by an endophytic fungus Umbelopsis isabellina.

Figure 35.

Biotransformation of 114 by an endophytic fungus Umbelopsis isabellina.

Microbial metabolism of triterpenoid

114 by various

Nocardia sp. NRRL 5646,

Nocardia sp. 44822 and

Nocardia sp. 44000 was investigated by D. Leipold

et al. Micobial conversion of

114 resulted methyl ester (

124), ursonic acid (

125), ursonic acid methyl ester (

126), 3-oxoursa-1,12-dien-28-oic acid (

127) and 3-oxoursa-1,12-dien-28-oic acid methyl ester (

128).

Nocardia sp. 45077 synthesized ursonic acid (

125) and 3-oxoursa-1,12-dien-28-oic acid (

127), while

Nocardia sp. 46002 produced only ursonic acid (

125).

Nocardia sp. 43069 did not cause any biotransformation of this compound [

45]. Microbial metabolism of

114 by

Aspergillus flavus (ATCC 9170) was studied by Ibrahim

et al., who showed the formation of 3-oxo ursolic acid derivative, ursonic acid (

125). These transformation reactions are shown in

Figure 36 [

46].

Figure 36.

Fermentation of ursolic acid (114) with Nocardia sp. and Aspergillus flavus.

Figure 36.

Fermentation of ursolic acid (114) with Nocardia sp. and Aspergillus flavus.

Microbial modification of

114 by an endophytic fungus

Pestalotiopsis microspora was carried out by S. Fu

et al. Incubation of

114 with

P. microspora afforded four metabolites: 3-oxo-15α,30-dihydroxy-urs-12-en-28-oic acid (

129), 3β,15α-dihydroxy-urs-12-en-28-oic acid (

130), 3β,15α,30-trihydroxy-urs-12-en-28-oic acid (

131) and 3,4-seco-ursan-4,30-dihydroxy-12-en-3,28-dioic acid (

132) (

Figure 37) [

47].

Lupane terpenoids are a group of pentacyclic triterpenoids that consist of compounds with antimalarial, vasorelaxant activities, and potent inhibitors against glycogen phosphorylase. Filamentous fungi,

Aspergillus ochraceus metabolized lupeol (

133) to two derivatives

134 and

135 (

Figure 38). Fermentation of

133 with

Mucor rouxii for 240 h yielded two other polar products:

136 and

137 [

48].

Figure 37.

Microbial metabolism of ursolic acid (114) with endophytic fungus Pestalotiopsis microspora.

Figure 37.

Microbial metabolism of ursolic acid (114) with endophytic fungus Pestalotiopsis microspora.

Figure 38.

Biotransformation of lupeol (133), produced by Aspergillus ochraceus and Mucor rouxii.

Figure 38.

Biotransformation of lupeol (133), produced by Aspergillus ochraceus and Mucor rouxii.

18β-Glycyrrhetinic acid (

138) is the active form of glycyrrhizin which is the major pentacyclic triterpene found in licorice (

Glycyrrhiza glabra L.). It is one of the principal constituents of traditional Chinese herbal medicine, the rhizome of

Glycyrrhiza uralensis (called Gancao). Glycyrrhetinic acid (

138) has been shown to possess several pharmacological activities, such as antiulcerative, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulating, antitumour activities, antiviral activity, interferon-inducibility, antihepatitis effects and anticancer activity. Several hydroxy derivatives of

138 enhanced anti-inflammatory, antioxidant activities, anti-proliferative and apoptotic activities. Several derivatives of

138 have already been used as pharmaceutical drugs [

49,

50,

51]. Many microorganisms catalyze

138 to its derivatives with structural diversity. Qin

et al. investigated metabolism of

138 with a fungus,

Cunninghamella blakesleeana AS 3.970 and reported the production of 3-oxo-7β-hydroxyglycyrrhetinic acid (

139) and 7β-hydroxyglycyrrhetinic acid (

140) (

Figure 39). Both metabolites showed activities against drug-resistant

Enterococcus faecalis [

49].

Xin

et al. investigated the microbial transformation of

138 by

Mucor polymorphosporus. Incubating

138 with

M. polymorphosporus (

Figure 40) for 10 days yielded five polar products: 6β,7β-dihydroxyglycyrrhentic acid (

141), 27-hydroxyglycyrrhentic acid (

142), 24-hydroxyglycyrrhentic acid (

143), 3-oxo-7β-hydroxyglycyrrhentic acid (

144) and 7α-hydroxyglycyrrhentic acid (

145) [

50].

Figure 39.

Biotransformation of glycyrrhetinic Acid (138) by Cunninghamella blakesleeana.

Figure 39.

Biotransformation of glycyrrhetinic Acid (138) by Cunninghamella blakesleeana.

Figure 40.

Biotransformation of 138 by Mucor polymorphosporus.

Figure 40.

Biotransformation of 138 by Mucor polymorphosporus.

Bioconversion of

138 using

Absidia pseudocylindrospora ATCC 24169,

Gliocladium viride ATCC 10097 and

Cunninghamella echinulata ATCC 8688a was carried out by G.T. Maatooq

et al. Fermentation of

138 afforded seven polar derivatives: 7β,15α-dihydroxy-18β-glycyrrhetinic acid (

146), 3-oxo-18β-glycyrrhetinic acid (

147), 15-hydroxy-18β-glycyrrhetinic acid (

148), 7β-hydroxy-18β-glycyrrhetinic acid (

149), 15α-hydroxy-18α-glycyrrhetinic acid (

150), 1α-hydroxy-18β-glycyrrhetinic acid (

151) and 13β-hydroxy-7α,27-oxy-12-dihydro-18β-glycyrrhetinic acid (

152) (

Figure 41). Compound

138,

146 and

150 enhanced the production of Nitric oxide (NO) in peritoneal rat macrophages treated with CCl

4 [

51].

Figure 41.

Biotransformation of 138 by Absidia pseudocylindrospora ATCC 24169, Gliocladium viride ATCC 10097 and Cunninghamella echinulata ATCC 8688a.

Figure 41.

Biotransformation of 138 by Absidia pseudocylindrospora ATCC 24169, Gliocladium viride ATCC 10097 and Cunninghamella echinulata ATCC 8688a.

Betulin (lup-20(29)-ene-3β, 28-diol,

153), also known as betulinic alcohol, is a pentacyclic triterpene alcohol with a lupane skeleton. The most widely reported source of

153 is the birch tree (

Betula sp.). It is also called betulinol and is structurally similar to sitosterols. It has estrogenic properties. Betulinic acid (

154), 3β-hydroxy-lup-20(29)-en-28-oic acid, an antimalarial triterpenoid present in many plant species such as birch tree (

Betula sp.),

Ziziphus sp.,

Syzygium sp.,

Diospyros sp. and

Paeonia sp. [

6]. It has attracted more and more attention due to its important physiological and pharmacological activities such as antitumor, anti-HIV, antiviral, anti-leukaemia, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antihelmintic, anti-feedant activities, antimalarial and anticancer activities [

6]. Betulinic acid (

154) and its derivatives are also potential bioactive compounds present in nature [

52,

53]. Biotransformation of betulin (

153) was carried out by Chen

et al. with the filamentous fungi,

Armillaria luteo-virens Sacc QH (ALVS),

Aspergillus foetidus ZU-G1 (AF) and

Aspergillus oryzae (AO), which resulted

154 in 6 days. Furthermore, Y. Feng

et al. investigated biotransformation of

153 to

154 by

Cunninghamella blakesleeana cells in 6 days of fermentation. These microbial reactions are described rin

Figure 42 [

52,

53].

Figure 42.

Microbial transformation of betulin (153) to betulinic acid (154) by Cunninghamella blakesleeana, Armillaria luteo-virens Sacc, Aspergillus foetidus and Aspergillus oryzae.

Figure 42.

Microbial transformation of betulin (153) to betulinic acid (154) by Cunninghamella blakesleeana, Armillaria luteo-virens Sacc, Aspergillus foetidus and Aspergillus oryzae.

Grishko

et al. reported regioselective oxidation of

153 into 3-oxo derivative, betulone (

155) by the resting cells of the actinobacterium

Rhodococcus rhodochrous IEGM 66 (

Figure 43) [

54]. Mao

et al. reported the fermentation of betulin (

153) by the yeast

Rhodotorula mucilaginosa. This resulted in the production of compound

155. Compound

155 exhibited 2 times higher antioxidative activity than that of

153. Regioselective oxidation of

153 into

155 with growing microorganism cells of marine fungi

Dothideomycete sp. HQ 316564 was reported by Li

et al. [

55,

56].

Figure 43.

Biotransformation of 153 to betulone (155) by Rhodococcus rhodochrous, Rhodotorula mucilaginosa and growing cultures of marine fungus Dothideomycete sp. HQ 316564 at pH 6.

Figure 43.

Biotransformation of 153 to betulone (155) by Rhodococcus rhodochrous, Rhodotorula mucilaginosa and growing cultures of marine fungus Dothideomycete sp. HQ 316564 at pH 6.

Preparation of betulinic acid derivatives through groups of fungi, such as

Mycelia sterilia,

Penicillium citreonigrum and

Penicillium sp. was investigated by Baratto

et al. M. sterilia converted

154 to an antimalarial agent [

6], betulonic acid (

156),

Penicillium sp. biotransformed

154 to

156 and methyl 3-oxolup-20(29)-en-28-oate (

157), and

P. citreonigrum transformed

156 to methyl 3-hydroxylup-20(29)-en-28-oate (

158). Biotranformation of

156 with carrot cell yielded 3-hydroxy-(20

R)-29-oxolupan-28-oic acid (

159) in 14 days [

57]. These biotransformations are shown in

Figure 44.

Figure 44.

Biotransformation of betulonic acid (154) with Mycelia sterilia, Penicillium sp. Penicillium citreonigrum and Daucus carota cells suspension.

Figure 44.

Biotransformation of betulonic acid (154) with Mycelia sterilia, Penicillium sp. Penicillium citreonigrum and Daucus carota cells suspension.

Nocardia sp. NRRL 5646 has been shown to produce a complex set of natural products to generate diverse structures [

58]. It has been used extensively to catalyze numerous biotransformations, including carboxylic acid and aldehyde reduction, phenol methylation, and flavone hydroxylation. Microbial transformation of

156 by

Nocardia sp. NRRL 5646 was investigated by Qian

et al. Fermentation of

156 for 6 days yielded asymmetric α-hydroxylation product, methyl 2α-acetoxy-3-oxo-lup-20(29)-en-28-oate (

160) and a methyl esterification of the C-28 carboxyl group, methyl 3-oxo-lup-20(29)-en-28-oate (

161) (

Figure 45) [

59].

Figure 45.

Microbial transformation of 156 by Nocardia sp. NRRL 5646.

Figure 45.

Microbial transformation of 156 by Nocardia sp. NRRL 5646.

Phytolaccagenin (2β,3β,23-trihydroxy-olean-12-ene-28,30-dioic acid 30-methyl ester,

162), a major aglycone constituent found in r

Phytolacca esculenta van Houtte.

Phytolacca esculenta is widely distributed in East Asia and is used as a crude drug against edema, theumatism, bronchitis and tumors in China, Korea and Japan. The roots of

P. esculenta are rich source of saponins and possess anti-inflammatory properties. They also induced immune interferons and tumor necrosis factor [

60]. Compound

162 exhibits high activity against acute inflammation. Regiospecific hydroxylation on the C-29 methyl group of

162 by

Streptomyces griseus ATCC 13273 was reported by Qian

et al. Fermentation of

162 with

S. griseus for 96-h afforded one polar metabolite, as 2β,3β,23,29-tetrahydroxy-olean-12-ene-28,30-dioic acid 30-methyl ester (

163) as shown in

Figure 46 [

60].

Figure 46.

Regio-specific microbial hydroxylation of phytolaccagenin (162) by Streptomyces griseus.

Figure 46.

Regio-specific microbial hydroxylation of phytolaccagenin (162) by Streptomyces griseus.

The gum resin of

Boswellia serrata has been used for the treatment of inflammatory and arthritic diseases. Its major active constituents are ursane triterpenoids, boswellic acids (BAs), which include 11-keto-β-boswellic acid (KBA,

164) (

Figure 47), acetyl-11-keto-β-boswellic acid (AKBA), β-boswellic acid (BA) and acetyl-β-boswellic acid (ABA). Among these, AKBA and KBA, possessing an 11-keto group, are the most bioactive compounds. They exhibited significant biological activities, including anti-inflammatory, anti-arthritis, anti-ulcerative colitis, anti-asthma, anticancer, and anti-hepatitis B properties [

61]. Microbial rmetabolism of

164 by

Cunninghamella blakesleeana AS 3.970 was studied by Wang

et al. Fermentation of

164 by

C. blakesleeana for 5 days yielded ten regioselective transformed products, which were characterized as 7β-hydroxy-11-keto-β-boswellic acid (

165); 7β,15α-dihydroxy-11-keto-β-boswellic acid (

166); 7β,16β-dihydroxy-11-keto-β-boswellic acid (

167); 7β,16α-dihydroxy-11-keto-β-boswellic acid (

168); 7β,22β-dihydroxy-11-keto-β-boswellic acid (

169); 7β,21β-dihydroxy-11-keto-β-boswellicacid (

170); 7β,20β-dihydroxy-11-keto-β-boswellic acid (

171); 7β,30-dihydroxy-11-keto-β-boswellic acid (

172); 3α,7β-dihydroxy-11-oxours-12-ene-24, 30-dioic acid (

173) and 3α,7β-dihydroxy-30-(2-hydroxypropanoyloxy)-11-oxours-12-en-24-oic (

174). These fungal transformation reactions are depicted in

Figure 47. Compound

167 and

171 exhibit significant inhibitory effect on nitric oxide (NO) production in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells [

55]. The location of the hydroxyl functionalities were deduced on the basis of the heteronuclear multiple bond connectivity (HMBC) interactions whereas orientations of OH groups were deduced on the basis of NOESY correlations [

61].

Fermentation of

164 with

Bacillus megaterium based on a recombinant cytochrome P450 system was reported by Bleif

et al. Metabolism of

164 yielded regio- and stereoselective 15α-hydroxylation of substrate

164 (

Figure 47). The structure was identified as 15α-hydroxy-KBA (

175) by NMR spectroscopy [

62].

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is the leading cause of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis which eventually leads to liver cancer. Echinocystic acid (3β,16α-dihydroxy-olean-12-en-28-oic acid,

176) (

Figure 48) is an oleanane-type triterpene, obtained from

Echinocystis fabacea that exhibits sustantial inhibition of HCV. Echinocystic acid (

176) and its saponins have been reported to have cytotoxic effects against different cell lines, including the J774.A1, HEK-293, WEHI-164 cell lines, the HepG2, HL-60 cells, the A375, Hela, and L929 cell lines

in vitro. Echinocystic acid (

176) and its saponins have many other bioactivities, including anti-HIV activities, antifungal activities, inhibitory activity toward pancreatic lipase, immunostimulatory effect, inhibition of mast cell degranulation, and the interleukin-18 inhibitory activities [

63,

64].

Figure 47.

Biotransformation of 11-keto-β-boswellic acid (164) by Cunninghamella blakesleeana and Bacillus megaterium.

Figure 47.

Biotransformation of 11-keto-β-boswellic acid (164) by Cunninghamella blakesleeana and Bacillus megaterium.

Microbial transformation of

176 by

Nocardia corallina CGMCC4.1037 was reported by Feng

et al. Incubation of

176 with

N. corallina CGMCC4.1037 resulted three polar metabolites: 3-oxo-16α-hydroxy-olean-12-en-28-oic acid (

177), 3β,16α-dihydroxy-olean-12-en-28-oic acid 28-

O-β-

d-glucopyranoside (

178), and 3-oxo-16α-hydroxy-olean-12-en-28-oic acid 28-

O-β-

d-glucopyranoside (

179) as described in

Figure 48 [

63]. Wang

et al. also reported the regio- and stereoselective modification of

176 by utlizing

Rhizopus chinensis CICC 3043 and

Alternaria alternata AS 3.4578 for lead for blocking HCV entry (see

Figure 49 and

Figure 50) [

64]. rThe major product from

R. chinensis CICC 3043-mediated biotransformation was acacic acid lactone (

180), along with five minor metabolites: 3β,6β,16α-trihydroxy-olean-12-en-28β-oic acid-21-lactone (

181), 1β,3β,16α-trihydroxy-olean-12-en-28β-oic acid-21-lactone (

182), 3β,16α-dihydroxy-olean-11,13(18)-dien-28β-oic acid-21-lactone (

183), 3β,7β,16α-trihydroxy-olean-12-en-28β-oic acid (

184) and 3β,7β,16α-trihydroxy-olean-11,13(18)-dien-28β-oic acid (

185) (

Figure 49). Furthermore,

A. alternata AS 3.4578-mediated metabolism of

176 yielded two major metabolites identified as 1β,3β,16α-trihydroxy-olean-11,13(18)-dien-28β-oic acid (

186) and

177, along with five minor metabolites:

183,

184,

185, 1β,3β,16α-trihydroxy-olean-12-en-28β-oic acid (

187), 3β,16α,29-trihydroxy-olean-12-en-28β-oic acid (

188), and 3-oxo-16α-hydroxy-olean-12-en-28β-oic acid (

189) as presented in

Figure 50 [

63,

64].

Figure 48.

Microbial metabolism of echinocystic acid (176) with Nocardia corallina CGMCC4.1037.

Figure 48.

Microbial metabolism of echinocystic acid (176) with Nocardia corallina CGMCC4.1037.

Figure 49.

Microbial metabolism of echinocystic acid (176) with Rhizopus chinensis CICC 3043.

Figure 49.

Microbial metabolism of echinocystic acid (176) with Rhizopus chinensis CICC 3043.

Figure 50.

Microbial metabolism of echinocystic acid (176) with Alternaria alternata AS 3.4578.

Figure 50.

Microbial metabolism of echinocystic acid (176) with Alternaria alternata AS 3.4578.

Corosolic acid (2β,3α-Dihydroxyurs-12-en-28-oic acid,

190), a naturally occurring pentacyclic triterpene, has been found in many traditional Chinese medicinal herbs, such as

Lagerstroemia speciosa,

Eriobotrta japonica,

Tiarella polyphylla,

etc. It has also been found in variety of plants, such as in apples, basil, bilberries, cranberries, and prunes, and has been shown to have a number of biological activities, including suppression of cell proliferation and induction of apoptosis in various cancer cell lines [

65,

66]. The growing cultures of

Fusarium equiseti CGMCC 3.3658 and

Gliocladium catenulatum CGMCC 3.3655 were used for structural modification of corosolic acid (

190) by Li

et al. Incubation with

F. equiseti CGMCC 3.3658 resulted two regioselective hydroxy metabolites 2α,3β,15α-trihydroxyurs-12-en-28-oic acid (

191) and 2α,3β,7β,15α-tetrahydroxyurs-12-en-28-oic acid (

192) as shown in

Figure 51.

G. catenulatum CGMCC 3.3655 transformed

190 into 2α,21β-dihydroxy-A-homo-3α-oxours-12-en-28-oic acid (

193), and 2α,3α,21β-trihydroxyurs-12-en-28-oic acid (

194) [

67] (

Figure 51).

Figure 51.

Microbial transformation of corosolic acid (190) by Fusarium equiseti and Gliocladium catenulatum.

Figure 51.

Microbial transformation of corosolic acid (190) by Fusarium equiseti and Gliocladium catenulatum.