Remote Query Resonant-Circuit Sensors for Monitoring of Bacteria Growth: Application to Food Quality Control

Abstract

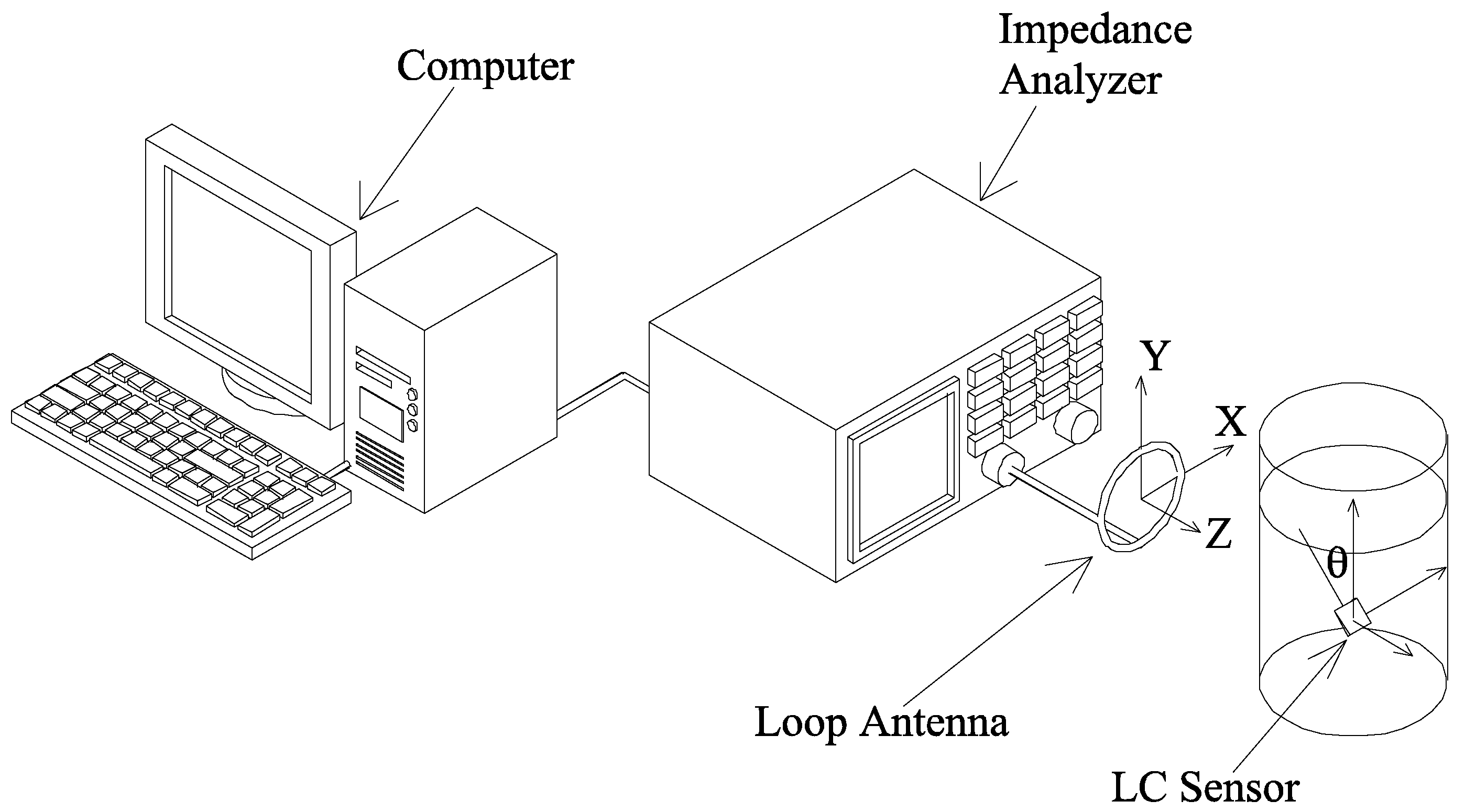

:Introduction

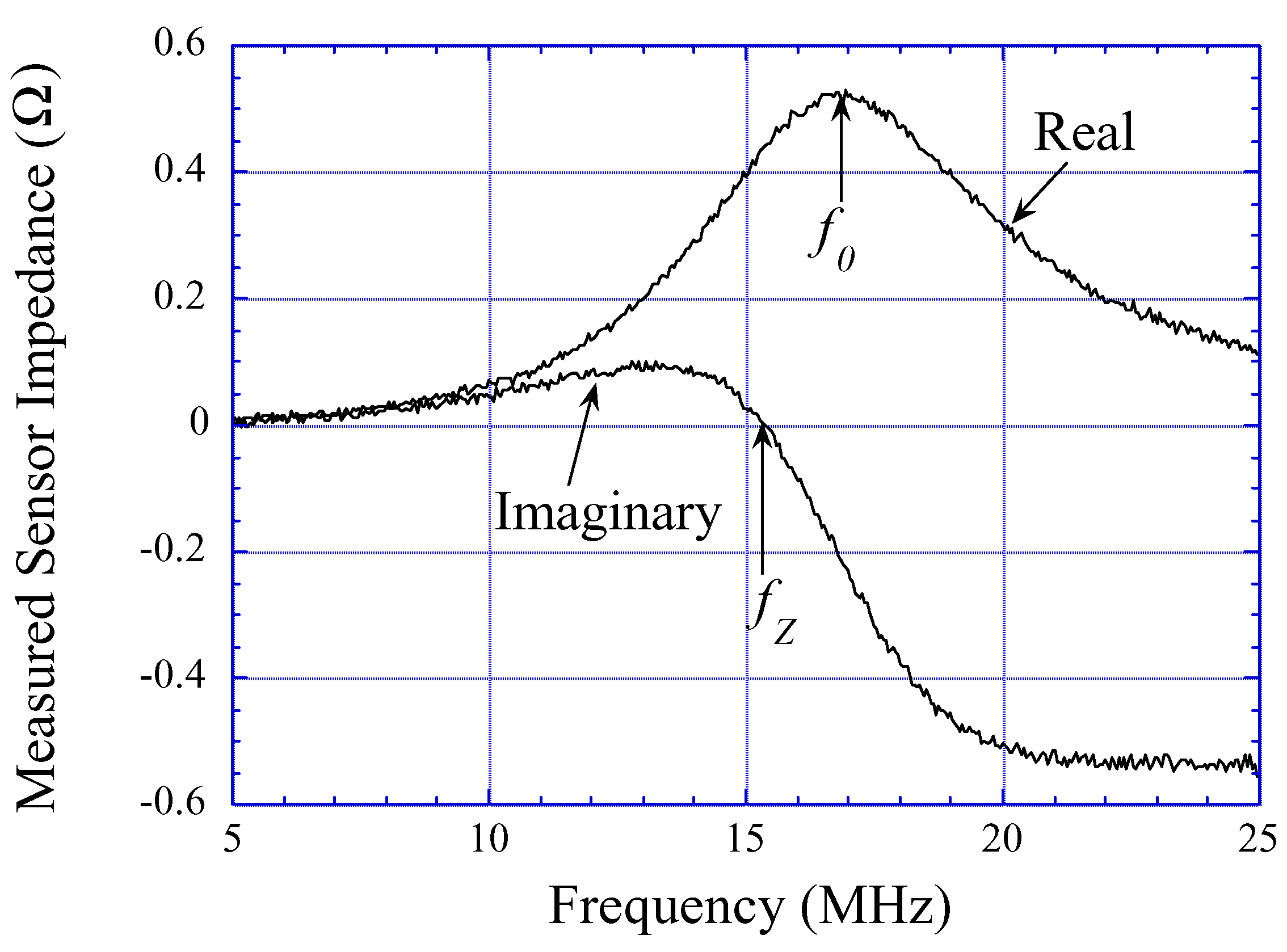

, is given as [18]:

, is given as [18]:

), κ is the cell constant of the interdigital capacitor, and L is the inductance of the spiral inductor in Henry’s. The cell constant κ and inductance L are calculated from the sensor geometry using [19,20]:

), κ is the cell constant of the interdigital capacitor, and L is the inductance of the spiral inductor in Henry’s. The cell constant κ and inductance L are calculated from the sensor geometry using [19,20]:

to the strip-line measurement

to the strip-line measurement  . The actual complex permittivity of the biological medium,

. The actual complex permittivity of the biological medium,  , is then calculated by multiplying the measured effective permittivity by the correction factor:

, is then calculated by multiplying the measured effective permittivity by the correction factor:

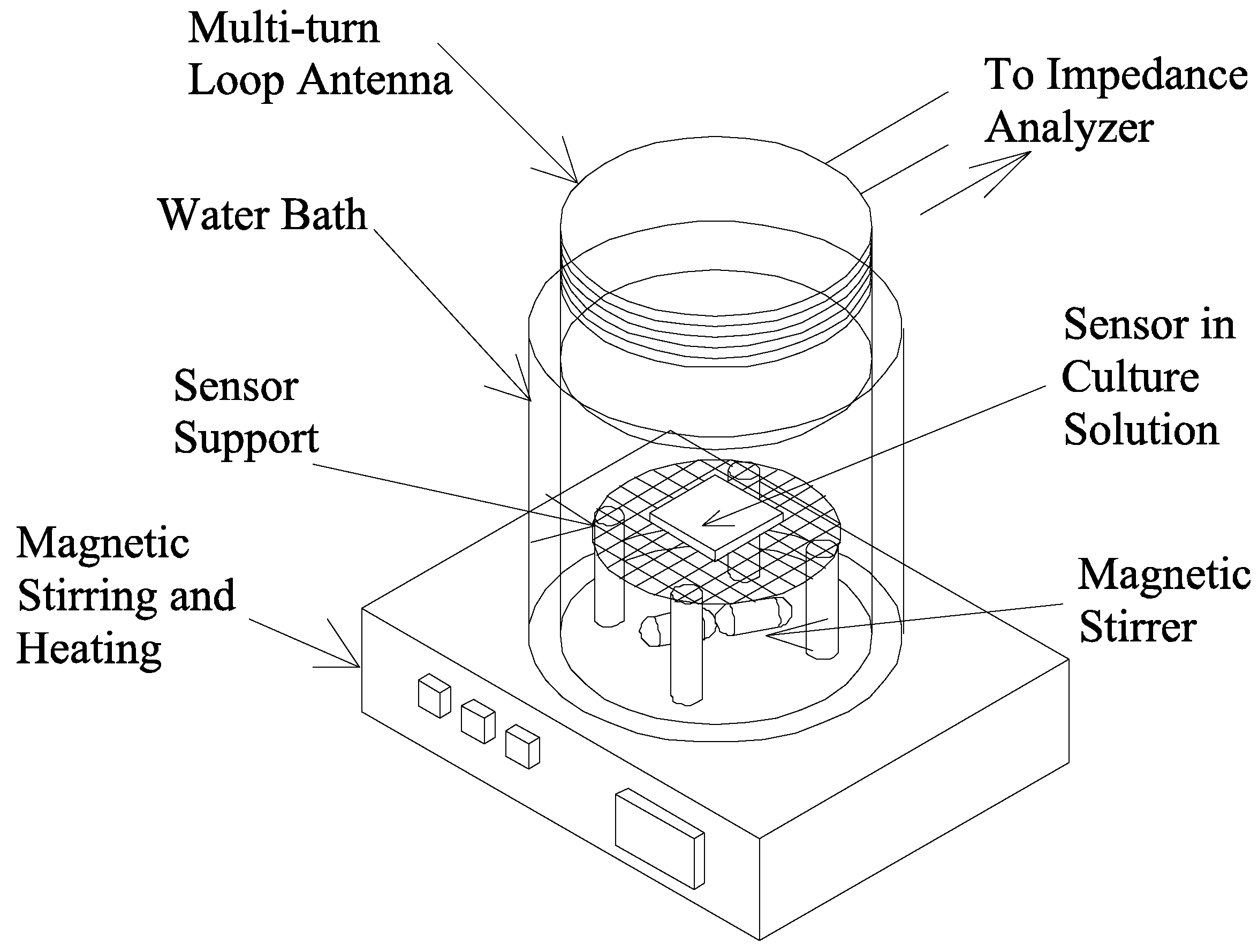

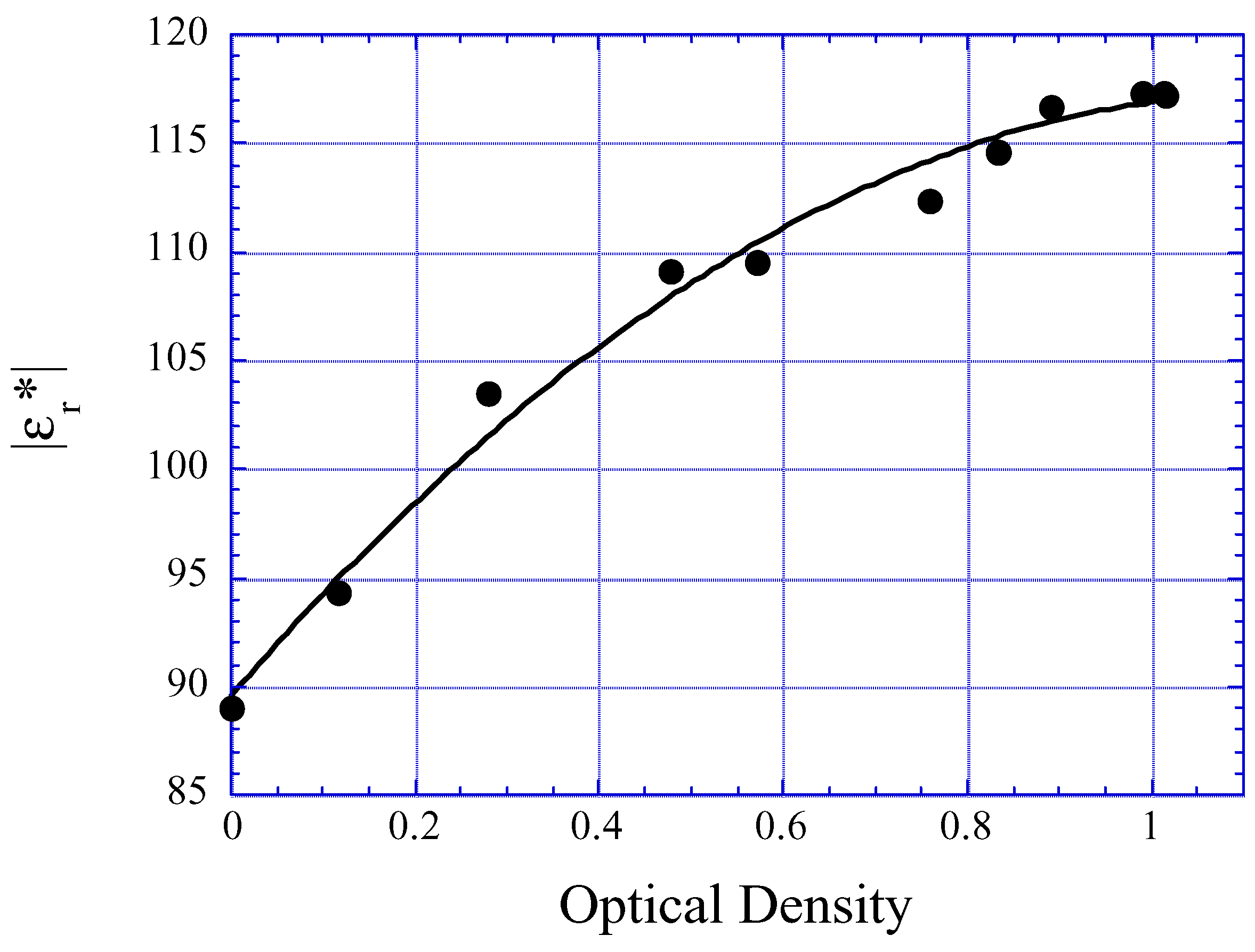

Experiments and Results

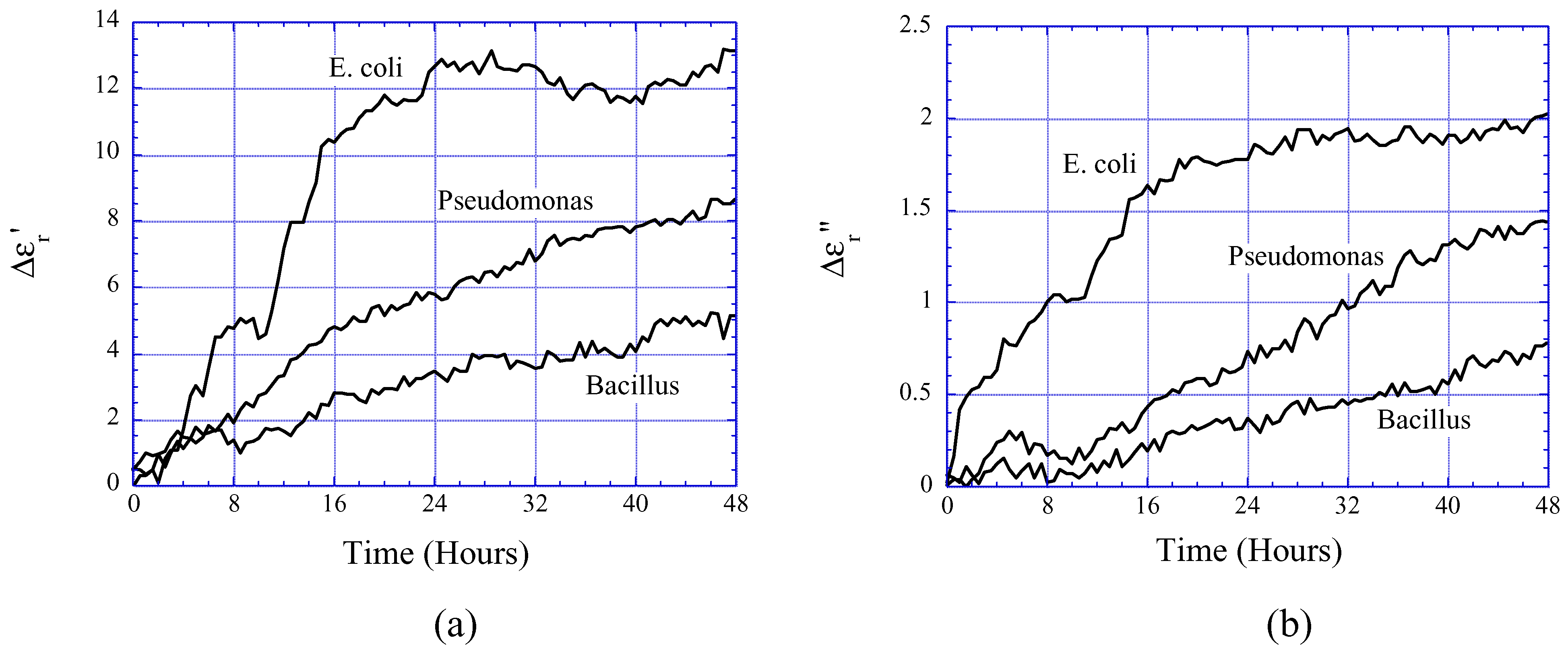

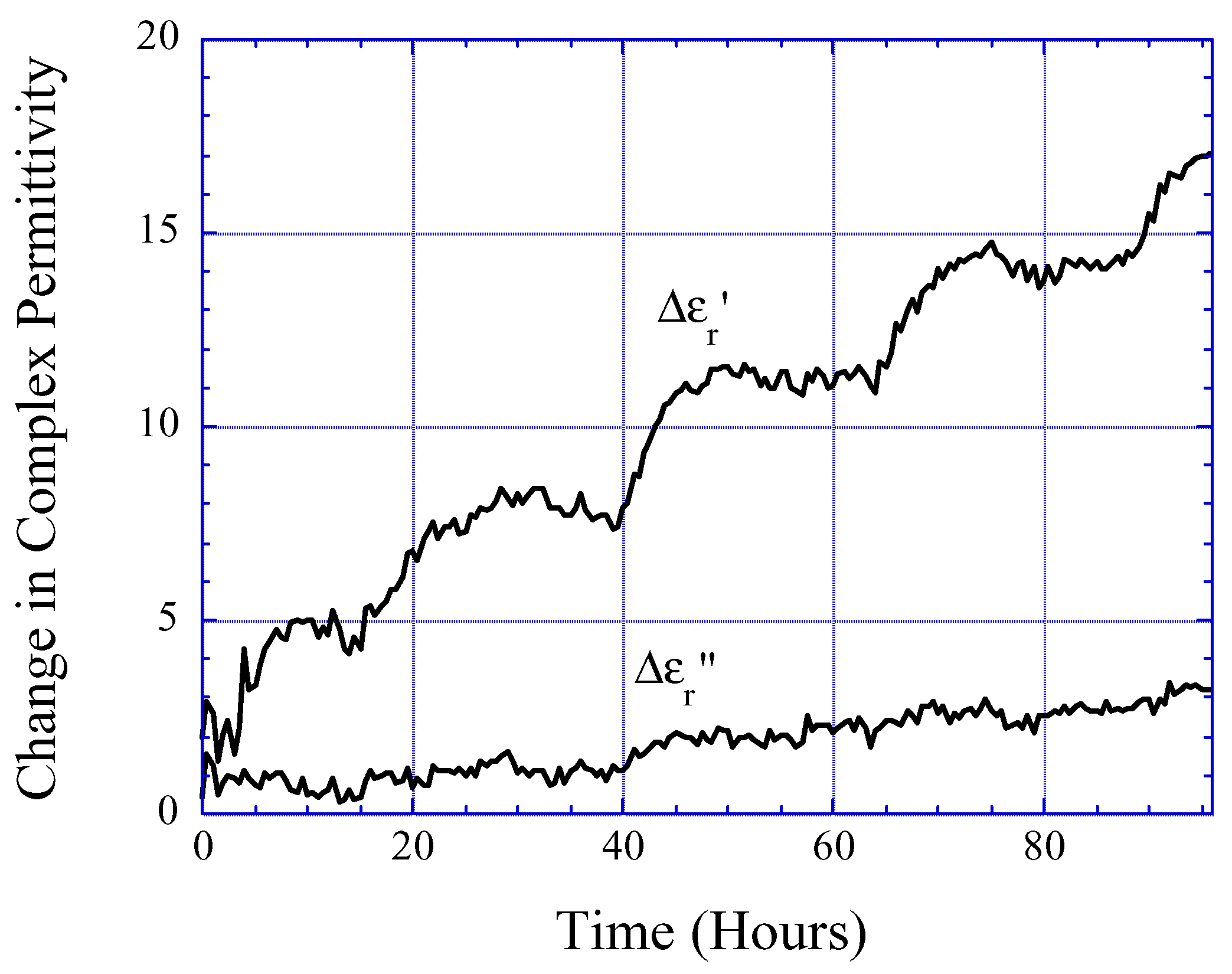

Bacteria Growth Monitoring

Food Quality Monitoring

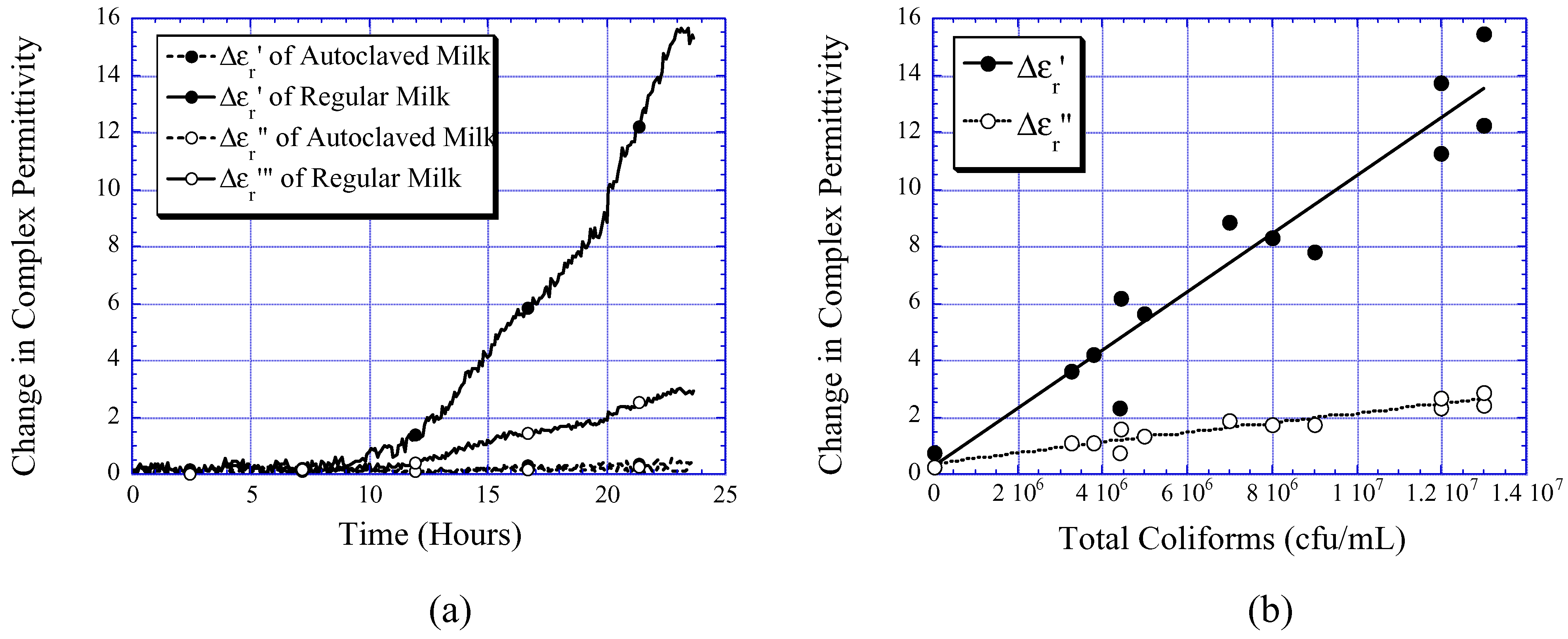

Milk Quality Monitoring

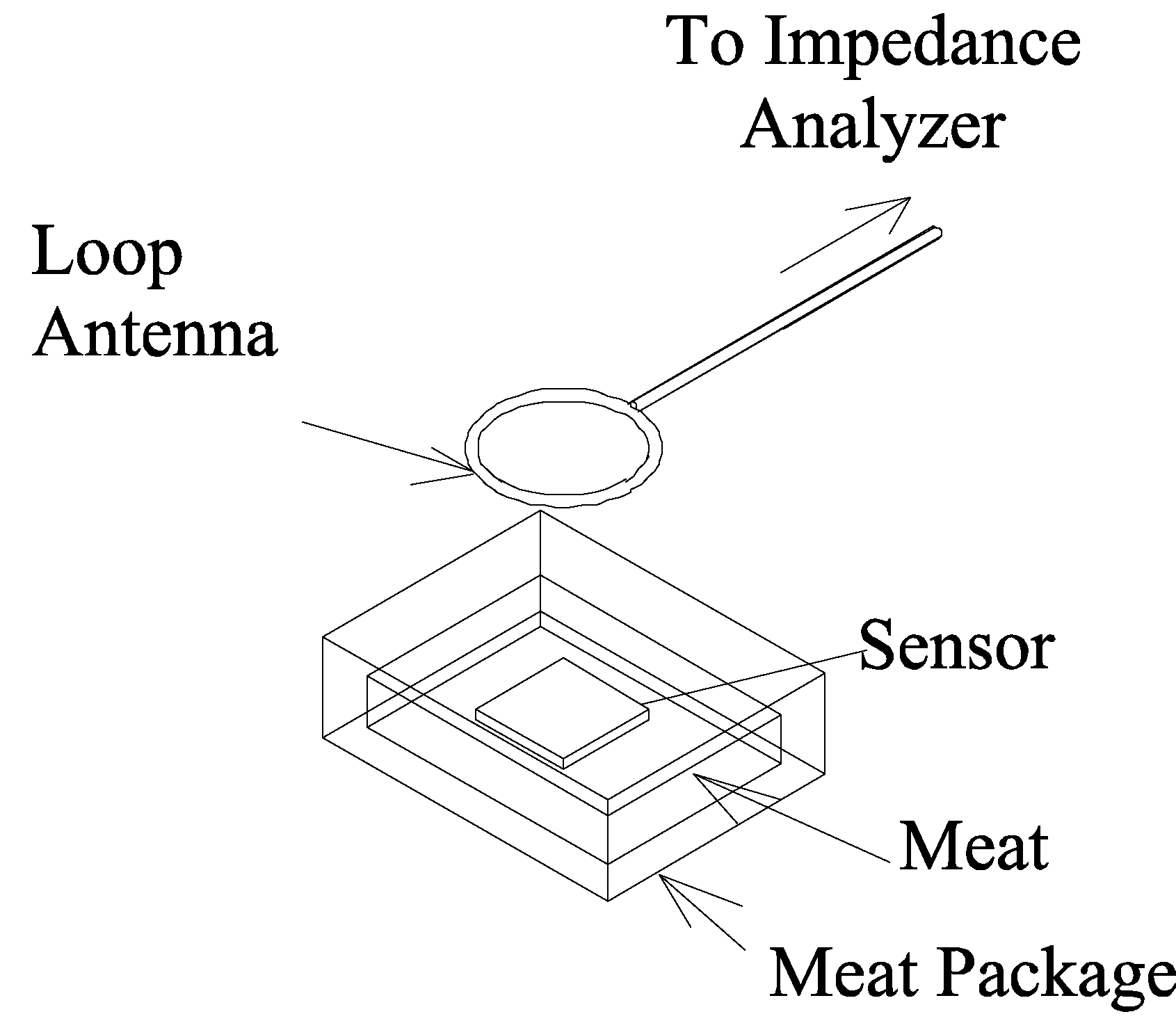

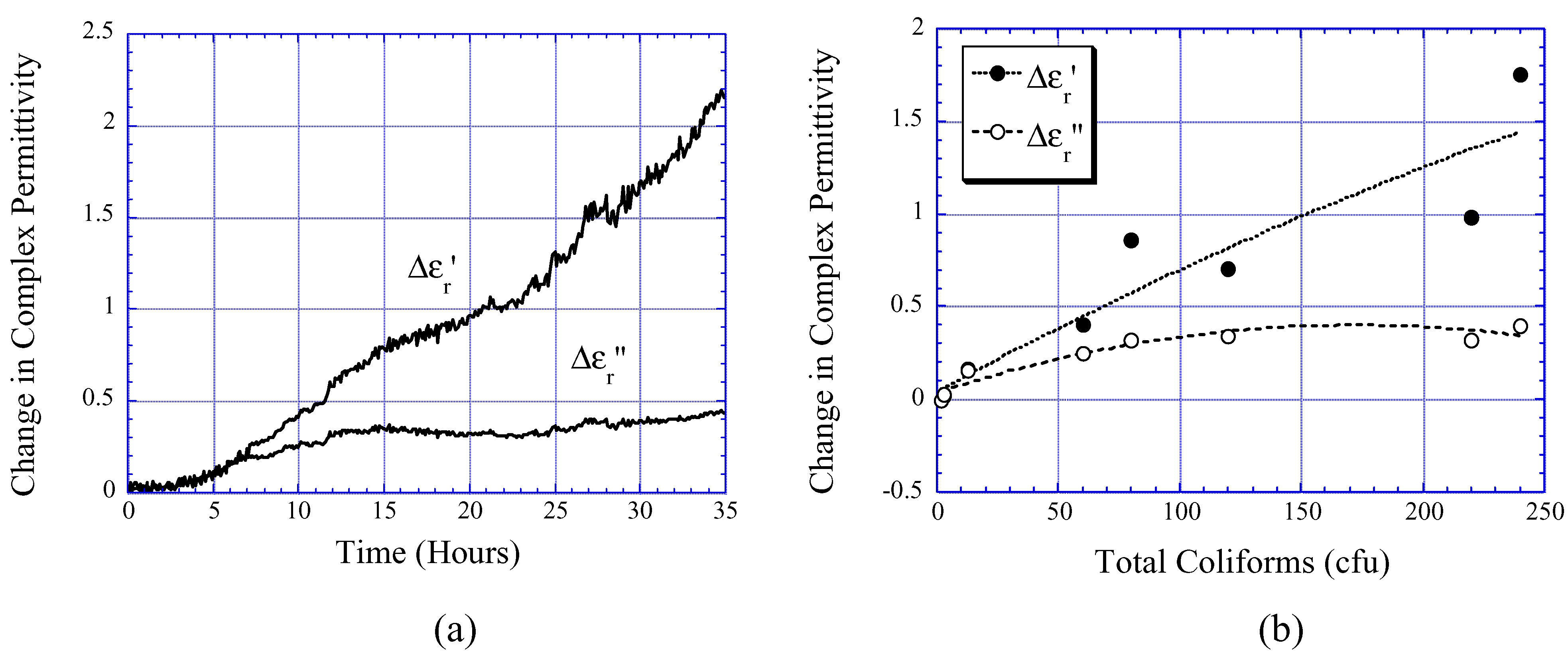

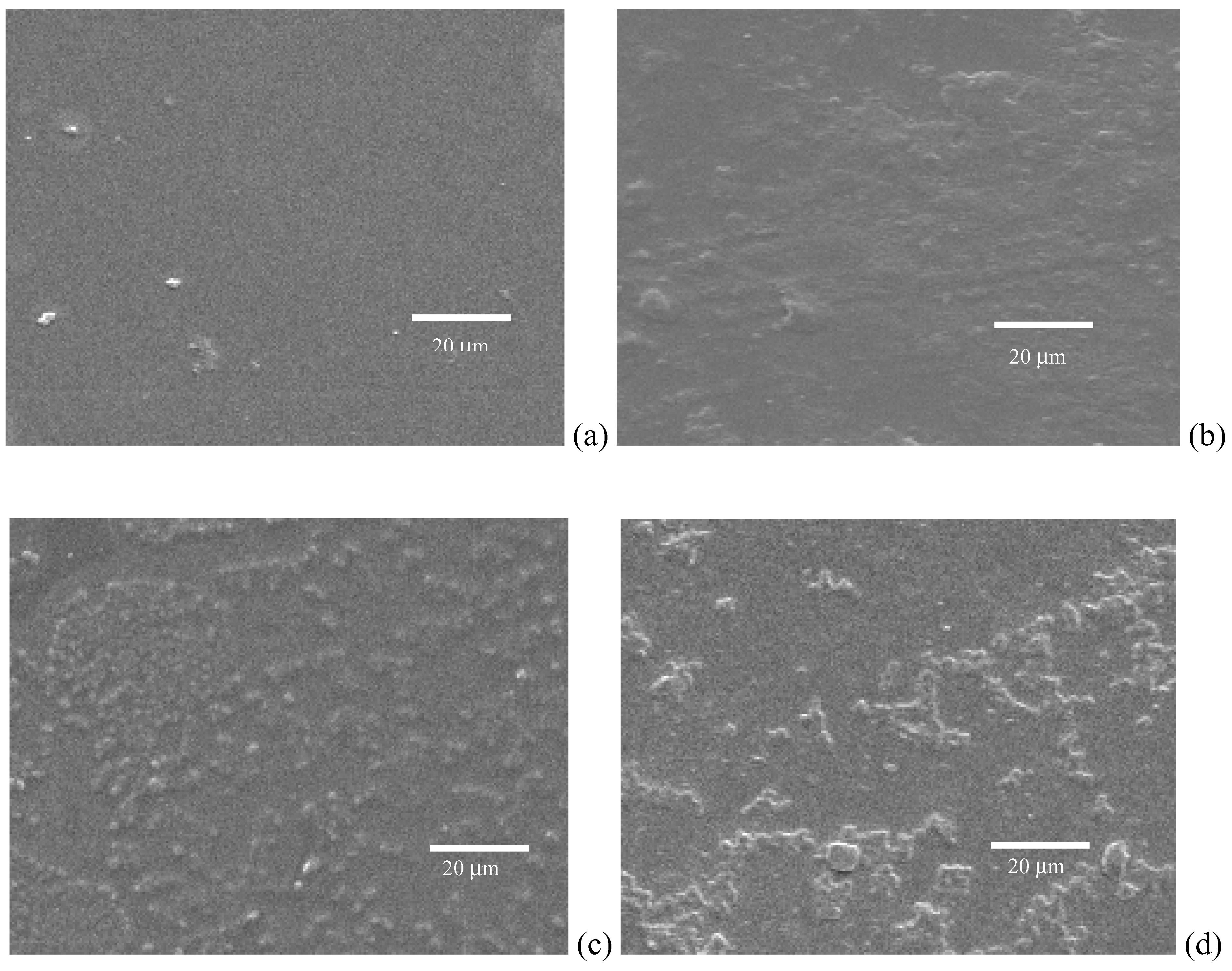

Meat Quality Monitoring

Beer Fermentation Monitoring

Performance and Limitations

Effects of Temperature and Coating Thickness

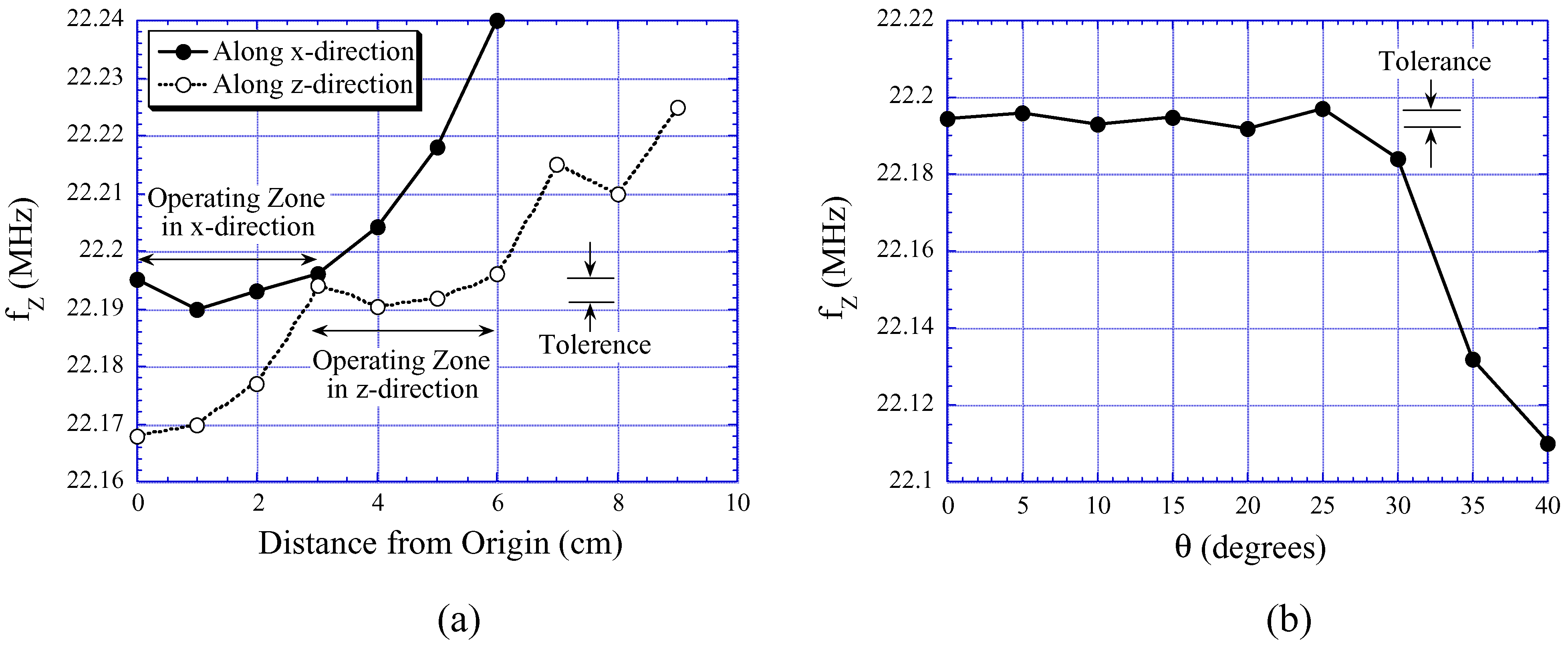

Effects of Sensor Location

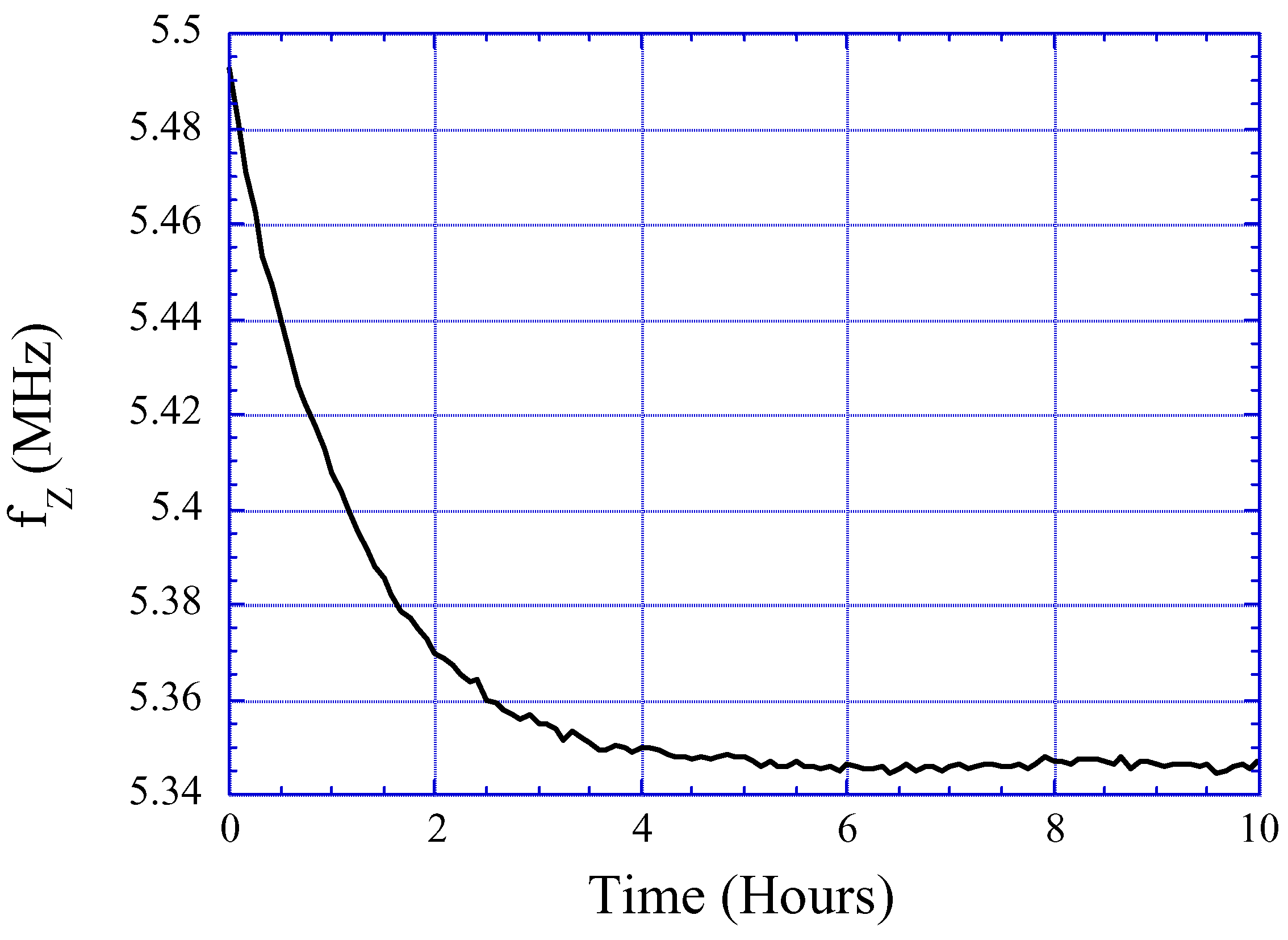

Effects of Water Absorption in the Sensor Surface

Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

- CDC data at http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/ss/ss4901.pdf

- Bishop, J.R.; White, C.H.; Firstenberg-Eden, R. Rapid impedimetric method for determining the potential shelf-life of pasteurized whole milk. J. Food Protect. 1984, 47(6), 471–475. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, P.A. Hypothetical model for monitoring microbial growth by using capacitance measurements – a minireview. Journal of Microbiological Methods 1999, 37, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firstenberg-Eden, R.; Eden, G. Impedance microbiology: Innovation in microbiology series 3; Research Studies Press: Letchworth, Hertfordshire, England; Wiley: NY, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Felice, C.J.; Valentinuzzi, M.E. Medium and interface components in impedance microbiology. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 1999, 46, 1483–1487. [Google Scholar]

- Felice, C.J.; Valentinuzzi, M.E.; Vercellone, M.I.; Madrid, R.E. Impedance bacteriometry: medium and interface contributions during bacterial growth. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 1992, 39, 1310–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, J.C.S.; Jason, A.C.; Hobbs, G.; Gibson, D.M.; Christie, R.H. Electronic measurement of bacteria growth. J. Phys. E: Sci. Instrum. 1978, 11, 560–568. [Google Scholar]

- Gnan, S.; Luedecke, L.O. Impedance measurements in raw milk as an alternative to the standard plate count. J. Food Protect. 1982, 45(1), 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Asami, K.; Gheorghiu, E.; Yonezawa, T. Dielectric behavior of budding yeast in cell separation. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1998, 1381, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asami, K.; Yonezawa, T. Dielectric analysis of yeast cell growth. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1995, 1245, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asami, K.; Yonezawa, T. Dielectric behavior of non-spherical cells in culture. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1995, 1245, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felice, C.J.; Madrid, R.E.; Olivera, J.M.; Rotger, V.I.; Valentinuzzi, M.E. Impedance microbiology: quantification of bacterial content in milk by means of capacitance growth curves. J. Microbiol. Methods 1999, 35, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firstenberg-Eden; Tricarico, M.K. Impedimetric determination of total, mesophilic and psychrotrophic counts in raw milk. J. Food Sci. 1983, 48, 1750–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cady, P.; Hardy, D.; Martins, S.; Dufour, S.W.; Kraeger, S.J. Automated impedance measurements for rapid screening of milk microbial count. J. Food Protect. 1978, 41, 277–283. [Google Scholar]

- Nielen, M.; Deluyker, H.; Schukken, Y.H.; Brand, A. Electrical conductivity of milk: measurement, modifiers, and meta analysis of mastitis detection performance. J. Diary Sci. 1992, 75, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firstenberg-Eden. Collaborative study of the impedance method for examining raw milk samples. J. Food Protect. 1984, 47(9), 707–712. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, K.G.; Grimes, C.A. A resonant printed-circuit sensor for remote query monitoring of environmental parameters. Smart. Mater. Struct. 2000, 9, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, K.G.; Grimes, C.A.; Robbins, C.L.; Singh, R.S. Design and application of a wireless, passive, resonant-circuit environmental monitoring sensor. Sen. Actuators A 2001, 3042, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markx, G.H.; Davey, C.L. The dielectric properties of biological cells at radio frequencies: applications in biotechnology. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 1999, 25, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, H. E. Printed inductors and capacitors. Tele-Tech & Electronic Industries 1954, 14, 68–69. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron, R.A. Theory of a strip-line cavity for measuring of dielectric constants and gyromagnetic-resonance line-widths. IEEE Trans. Microwave Theory Tech. 1964, 1, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sample Availability: Available from the authors.

© 2002 by MDPI (http://www.mdpi.net) Reproduction is permitted for noncommercial purposes.

Share and Cite

Ong, K.G.; Bitler, J.S.; Grimes, C.A.; Puckett, L.G.; Bachas, L.G. Remote Query Resonant-Circuit Sensors for Monitoring of Bacteria Growth: Application to Food Quality Control. Sensors 2002, 2, 219-232. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20600219

Ong KG, Bitler JS, Grimes CA, Puckett LG, Bachas LG. Remote Query Resonant-Circuit Sensors for Monitoring of Bacteria Growth: Application to Food Quality Control. Sensors. 2002; 2(6):219-232. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20600219

Chicago/Turabian StyleOng, Keat Ghee, J. Samuel Bitler, Craig A. Grimes, Libby G. Puckett, and Leonidas G. Bachas. 2002. "Remote Query Resonant-Circuit Sensors for Monitoring of Bacteria Growth: Application to Food Quality Control" Sensors 2, no. 6: 219-232. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20600219

APA StyleOng, K. G., Bitler, J. S., Grimes, C. A., Puckett, L. G., & Bachas, L. G. (2002). Remote Query Resonant-Circuit Sensors for Monitoring of Bacteria Growth: Application to Food Quality Control. Sensors, 2(6), 219-232. https://doi.org/10.3390/s20600219