1. Introduction

With great advantages of unique ecological environments, powerful gene clusters, and high yields of secondary metabolites, marine-derived fungi represent a gigantic and insufficiently untapped reservoir for the exploration of novel bioactive marine natural products (MNPs) [

1,

2,

3]. One promising family of such MNPs is the mycophenolic acid (MPA) family, which was mainly discovered in the

Penicillium genus, such as

P. brevicompactum,

P. viridicatum,

P. griscobrunneum,

P. stoloniferum, etc. [

4]. Since the first report of MPA in 1893 [

5], the MPA and its derivatives have attracted much attention from phytochemists and pharmacologists because of their wide array of bioactivities, such as immunosuppressive, antitumor, antiviral, and RNA capping inhibitory properties [

6]. Over the last decades, the studies on MPA and its derivatives are the hotspot fields owing to their potentials to provide natural chemotypes for the discovery of new therapeutic agents; for instance, MPA is a well-known non-competitive and reversible inhibitor of inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH), which is responsible for regulating the biosynthesis of intracellular guanine nucleotide, and thus is of great importance for the DNA and RNA synthesis, signal transduction, energy source for translation, glycoprotein synthesis, as well as other cellular proliferation processes [

7]. More importantly, as the 2-morpholinoethyl ester prodrug of MPA, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) has been widely used as a clinical immunosuppressant in heart, kidney, lung and liver transplantation processes [

8]. However, the frequently occurred side effects such as leukopenia and gastrointestinal disorders, particularly diarrhea restricted the use of MMF in clinical practice [

8]. Therefore, the exploration is still on the way for more effective analogues that are non-toxic or of low toxicity and beneficial to improve the quality of life of patients.

As part of our program aiming at exploring structurally unique natural products with interesting bioactivities from fungi inhabiting unique environments [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14], a coral-derived fungus

Penicillium bialowiezense was cultivated in the solid-state fermented rice medium. By virtue of effective bioassay-guided fractionation and purification, eleven mycophenolic acid derivatives, including five previously unreported metabolites (

3–

7) and six known compounds (

1,

2, and

8–

11), were obtained. Herein, we report the isolation, structure elucidation, and immunosuppressive activity for all these compounds (

Figure 1).

2. Results

Compounds

3 and

4, both isolated as white powders, gave the identical molecular formula C

18H

22O

7 based on their HRESIMS

m/

z 373.1260 [M + Na]

+ and 373.1282 [M + Na]

+ (calcd. for C

18H

22O

7Na, 373.1263) as well as the

13C-NMR and DEPT data, indicating eight degrees of unsaturation. The IR spectrum of

3 showed absorptions of hydroxyl (3435 cm

−1), ester carbonyl (1744 cm

−1), and aromatic ring (1626 and 1456 cm

−1). The

1H-NMR spectrum (

Table 1) of

3 showed characteristic signals attributable to two methyl groups at

δH 1.81 (3H, s, Me-7′) and 2.20 (3H, s, Me-8), two methoxyl groups at

δH 3.54 (3H, s, OMe-3) and 3.75 (3H, s, OMe-5), and one olefinic proton at

δH 5.25 (

1H, t,

J = 6.9 Hz). The

13C-NMR and DEPT spectra (

Table 2) showed the presence of 18 carbon signals, including four methyls (two oxygenated), three sp

3 methylenes, one sp

2 methine, one oxygen-bearing sp

3 methine, seven sp

2 quaternary and two carbonyl carbons. These data suggested that

1 was a MPA derivative.

The

1H and

13C-NMR data (

Table 1 and

Table 2) of

3 resembled those of

2, except for the presence of a methoxyl group (

δH 3.54;

δC 56.4) in

3 instead of a hydroxyl group on C-3 in

2, as demonstrated by the HMBC correlation from H-3 (

δH 6.34) to the methoxyl carbon (

δC 56.4). Comparison of the

1H and

13C-NMR data (

Table 1 and

Table 2) of

4 with those of

2 revealed that the C-6′ carboxyl group in

2 was methyl-esterified in

4, which was confirmed by the HMBC correlation from 6′-OMe (

δH 3.60) to the ester carbonyl carbon at

δC 174.1. Compounds

3 and

4 were optically inactive since they showed no Cotton effects in the experimental CD spectra, suggesting that they were also racemic. Unfortunately, an attempt to separate the enantiomers of

3 and

4 was not successful. Accordingly, the structures of

3 and

4 were elucidated as 6-(5-carboxy-3-methylpent-2-enyl)-7-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxy-4-methylphthalan-1-one and 6-(5-methoxycarbonyl-3-methylpent-2-enyl)-3,7-dihydroxy-5-methoxy-4-methylphthalan-1-one, respectively.

Compound

5 was purified as a white powder. Its molecular formula C

15H

18O

6 was assigned based on the HRESIMS

m/

z 317.1007 [M + Na]

+ (calcd. for C

15H

18O

6Na, 317.1001). The NMR data of

5 (

Table 3) closely resembled those of euparvic acid [

15], whose absolute structure was confirmed by X-ray crystallography. The only difference was that the C-5 hydroxy group in euparvic acid was replaced by a methoxyl group (

δH 3.79;

δC 61.6) in

5, as supported by the HMBC correlation from the methoxyl proton to C-5 (

δC 164.9) (

Figure 2). As the specific rotations of

5 {[α

: –6.6 (

c 0.01, MeOH)} and euparvic acid {[

α: –4.0 (

c 0.01, MeOH)} were levorotatory, it was suggested that the absolute configuration of C-3′ in

5 should be the same as that of C-3′ of euparvic acid, i.e., 3′

S. Thus, the structure of

5 was identified as 6-(3-carboxybutyl)-7-hydroxy-5-methoxy-4-methylphthalan-1-one.

Compound

6 was also isolated as a white, amorphous powder. The HRESIMS analysis of

6 showed a positive molecular ion peak at

m/

z 417.1495 [M + Na]

+ (calcd. for C

20H

26O

8Na, 417.1525), corresponding to a molecular formula C

20H

26O

8. Comparison of its

1H and

13C-NMR data (

Table 1 and

Table 2) with those of

11 revealed that

6 was 2,3-dihydroxypropyl mycophenolate. This structure was supported by the

1H–

1H COSY correlations from H-8′ through H-10′ and HMBC correlation from H

2-8′ (

δH 3.98 and 4.06) to C-6′ (

δC 174.8) (

Figure 2). The specific rotation of

6 was approximately zero, indicating that

6 was also a racemic mixture. Thus, compound

6 was named 6-[5-(2,3-dihydroxy-1-carboxyglyceride)-3-methylpent-2-enyl]-7-hydroxy-5-methoxy-4-methylphthalan-1-one.

The molecular formula of

7 was assigned as C

21H

27NO

7 from the HRESIMS

m/

z 428.1708 [M + Na]

+ (calcd. for C

21H

27NO

7Na, 428.1685). The

1H and

13C-NMR data of

7 (

Table 1 and

Table 2) were similar to those of

6, except for the presence of a 4-aminobutanoic acid moiety instead of the 2,3-dihydroxypropyl group. This hypothesis was confirmed by the

1H–

1H COSY correlations from H-2″ through H-4″ and HMBC correlations from H

2-2″ (

δH 3.11) to C-6′ (

δC 175.8) and from H

2-3″ (

δH 1.68) and H

2-4″ (

δH 2.24) to C-5″ (

δC 177.2) (

Figure 2). Thus, the structure of

7 was elucidated as 6-[5-(1-carboxy-4-

N-carboxylate)-3-methylpent-2-enyl]-7-hydroxy-5-methoxy-4-methylphthalan-1-one.

Compounds

1–

2 and

8–

11 were identified as 8-

O-methyl mycophenolic acid (

1) [

16], 3-hydroxy mycophenolic acid (

2) [

16],

N-mycophenoyl-

l-valine (

8) [

8],

N-mycophenoyl-

l-phenyloalanine (

9) [

8],

N-mycophenoyl-

l-alanine (

10) [

8], and MPA (

11) [

17] by comparison of their NMR data and specific rotations with those reported in the literature. Moreover, their structures were confirmed by

1H–

1H COSY and HMBC correlations (for detailed structural determination, please see the

Supporting Information).

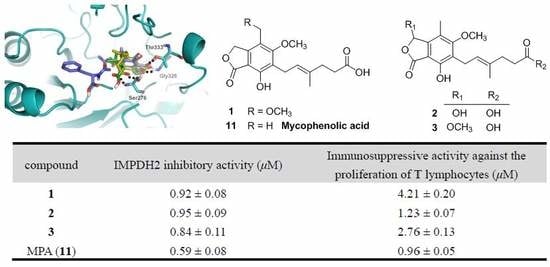

To assess the biological activity of the MPA derivatives, we primarily evaluated their IMPDH2 inhibitory activity with the previously reported enzyme assay method [

18]. The results (

Table 4) revealed that all these compounds could inhibit IMPDH2 with IC

50 values ranging from 0.59 to 24.68 µM, of which compounds

1–

3 were comparable to that of MPA (the positive control), suggesting that hydroxylation or methoxylation of the main skeleton (7-hydroxy-5-methoxy-4-methylphthalan-1-one moiety) minimally affected the IMPDH2 inhibition, while esterification of hexenoic acid tail dramatically decreased the IMPDH2 inhibitory activity, which was in accordance with that of mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) [

19]. Subsequently, the MPA derivatives were further tested for the in vitro immunosuppressive activity against the proliferation of T lymphocytes. Unsurprisingly, the activity at the cellular level was markedly consistent with their IMPDH2 inhibitory activity.

To further investigate their structure-activity relationships and modes of action, the binding modes and docking scores of compounds with IMPDH2 were obtained by molecular docking [

20]. As shown in

Figure 3, compounds

3 and

9 with considerable different levels on the activeness of enzyme were chosen to compare with MPA. The main skeleton was deeply buried into the binding pocket with several hydrogen bonds between these compounds and IMPDH2 observed, which included hydrogen bonds between the lactone oxygen (O-2) and the amide nitrogen of Gly326, and the carbonyl (C-1) oxygen and hydroxyl group of Thr333. Moreover, the hexenoic acid tail of

3 and MPA could adopt a bent conformation which allowed the carboxylate group to form hydrogen bonds with the amide nitrogen and side-chain hydroxyl groups of Ser276, thus the collective data from both bioassays and virtual docking revealed the importance of the hydrogen interactions in the immunosuppressive activity displayed by the MPA scaffold at both the enzymatic and cellular levels.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Experimental Procedures

Optical rotations were measured by using a PerkinElmer 341 instrument. UV and FT-IR spectra were recorded by using a Varian Cary 50 and a Bruker Vertex 70 instrument, respectively. High-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HRESIMS) were performed by using the positive ion mode with a Thermo Fisher LC-LTQ-Orbitrap XL spectrometer. The 1D (1H, 13C, DEPT) and 2D (HSQC, HMBC, 1H–1H COSY) NMR spectra were recorded by using Bruker AM-400 and DRX-600 instruments with tetramethylsilane as an internal standard, and the chemical shifts (δ) were expressed in ppm and referenced to the solvent signals (δH 3.31 and δC 49.0 for CD3OD). Semi-preparative HPLC were performed by using an Agilent 1200 liquid chromatograph with a Zorbax SB-C18 (9.4 mm × 25 cm) column. Column chromatography (CC) was performed by using Silica gel (200–300 mesh; Qingdao Marine Chemical, Inc., Qingdao, China), Sephadex LH-20 (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences AB, Uppsala, Sweden), and Lichroprep RP-C18 gel (40–63 μm, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Analytical Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed with precoated silica gel 60 F254 glass plates (200–250 μm thickness, Qingdao Marine Chemical Inc.), and spots were visualized by spraying heated silica gel plates with 10% H2SO4 in EtOH.

3.2. Fungal Material

The strain Penicillium bialowiezense was isolated from the fresh the soft coral Sarcophyton subviride, which was collected from the Xisha Island (16°45′ N, 111°65′ E) in the South China Sea in October 2016. The strain was authenticated by one of the authors (J. Wang), according to its morphology and sequence analysis of the ITS region of the rDNA (GenBank accession MH443003). The fungal sample was preserved in the culture collection center of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

3.3. Fermentation, Extraction, and Bioassay-Guided Isolation Procedures

The strain Penicillium bialowiezense was incubated on potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium at 26 °C for 7 days in stationary phase to prepare the seed cultures, which were then cut into small pieces (nearly 0.4 × 0.4 × 0.4 cm) and inoculated into 300 × 500 mL Erlenmeyer flasks (compositions: 200 g rice and 200 mL distilled water), previously sterilized by autoclaving. All flasks were incubated at 28 °C for 40 days. Following incubation, the growth of cells was stopped by adding 300 mL EtOAc to each flask, and the culture was homogenized. The fermented materials were extracted with EtOAc (30 L) for eight times, and under reduced pressure the organic solvent was evaporated to dryness to give a dark brown crude extract (600 g), which showed a moderate immunosuppressive activity against the proliferation of T lymphocytes at a concentration of 33.6 ± 0.41 μg/mL.

The total extract (600 g) was subjected to silica gel CC (100–200 mesh), eluted with a gradient of petroleum ether–EtOAc–MeOH (20:1:0 to 1:1:1) to give eight fractions (Fr.1–Fr.8), which were evaluated for immunosuppressive activity against the proliferation of T lymphocytes. As a result, only Fr.4 (petroleum ether–EtOAc, 2:1) and Fr.5 (petroleum ether–EtOAc, 1:1) showed obvious inhibitory activity at concentrations of 1.42 ± 0.15 and 11.68 ± 0.83 μg/mL, respectively. Then, Fr.4 (140 g) was subjected to YMC RP-C18 CC (MeOH–H2O, 20% to 100%) to give five subfractions (Fr.4.1–Fr.4.5). Compound 11 (50 g) crystallized from Fr.4.3 (MeOH–H2O, 60%, 100 g), and the residue was loaded onto Sephadex LH-20 (CH2Cl2–MeOH, 1:1), silica gel CC (CH2Cl2–MeOH, 60:1), and repeated semi-preparative HPLC (MeOH–H2O, 70:30, 2.0 mL/min) to yield compounds 1 (7.9 mg), 2 (17.3 mg), 3 (20.5 mg), 4 (4.2 mg), and 5 (11.3 mg). Fr.5 (100 g) was separated into five subfractions by RP-C18 CC (MeOH–H2O, 20% to 100%). Fr.5.3 (MeOH–H2O, 60%, 65 g) was further purified by Sephadex LH-20 (CH2Cl2–MeOH, 1:1), silica gel CC using CH2Cl2–MeOH (stepwise 50:1 to 30:1), and repeated semi-preparative HPLC eluted with MeOH–H2O (65:35, 2 mL/min) or CH3CN–H2O (60:40, 2 mL/min) to afford compounds 6 (10.2 mg), 7 (10.4 mg), 8 (9.2 mg), 9 (21.6 mg), and 10 (8.5 mg).

6-(5-Carboxy-3-methylpent-2-enyl)-7-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxy-4-methylphthalan-1-one (

3): white powder; UV (MeOH) λ

max (log

ε): 219 (4.48), 253 (3.75), and 309 (3.57) nm; IR (

νmax): 3435, 2923, 2853, 1744, 1626, 1456, 1416, 1382, 1208, 1138, 1073, 908, 676 cm

−1; HRESIMS

m/

z 373.1260 [M + Na]

+ (calcd. for C

18H

22O

7Na, 373.1263);

1H and

13C-NMR data, see

Table 1 and

Table 2.

6-(5-Methoxycarbonyl-3-methylpent-2-enyl)-3,7-dihydroxy-5-methoxy-4-methylphthalan-1-one (

4): white powder; UV (MeOH) λ

max (log

ε): 218 (4.50), 251 (3.79), and 311 (3.64) nm; IR (

νmax): 3442, 2922, 2852, 1739, 1643, 1466, 1440, 1382, 1278, 1093, 683 cm

−1; HRESIMS

m/

z 373.1282 [M + Na]

+ (calcd. for C

18H

22O

7Na, 373.1263);

1H and

13C-NMR data, see

Table 1 and

Table 2.

6-(3-Carboxybutyl)-7-hydroxy-5-methoxy-4-methylphthalan-1-one (

5): white powder; [α

: –6.6 (

c 0.01, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λ

max (log

ε): 217 (4.35), 252 (3.71), and 307 (3.39) nm; IR (

νmax): 3423, 2925, 2854, 1732, 1619, 1462, 1413, 1378, 1322, 1196, 1141, 1034, 967, 678 cm

−1; HRESIMS

m/

z 317.1007 [M + Na]

+ (calcd. for C

15H

18O

6Na, 317.1001);

1H and

13C-NMR data, see

Table 3.

6-[5-(2,3-Dihydroxy-1-carboxyglyceride)-3-methylpent-2-enyl]-7-hydroxy-5-methoxy-4-methylphthalan-1-one (

6): white powder; [α

: 0 (

c 0.5, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λ

max (log

ε): 217 (4.24), 251 (3.47), and 306 (3.15) nm; IR (

νmax): 3396, 2922, 2851, 1736, 1646, 1456, 1415, 1382, 1271, 1137, 1080, 1033, 972, 647 cm

−1; HRESIMS

m/

z 417.1495 [M + Na]

+ (calcd. for C

20H

26O

8Na, 417.1525);

1H and

13C-NMR data, see

Table 1 and

Table 2.

6-[5-(1-Carboxy-4-

N-carboxylate)-3-methylpent-2-enyl]-7-hydroxy-5-methoxy-4-methylphthalan-1-one (

7): white powder; UV (MeOH) λ

max (log

ε): 217 (4.46), 251 (3.72), and 306 (3.43) nm; IR (

νmax): 3420, 2924, 2853, 1736, 1633, 1454, 1412, 1377, 1328, 1276, 1193, 1136, 1078, 1030, 970, 792, 652, 597 cm

−1; HRESIMS

m/

z 428.1708 [M + Na]

+ (calcd. for C

21H

27NO

7Na, 428.1685);

1H and

13C-NMR data, see

Table 1 and

Table 2.

3.4. Biological Assays

Each compound was first dissolved in DMSO and then diluted with distilled water to the desired concentration.

3.4.1. IMPDH2 Expression and Purification

The gene encoding IMPDH2 was cloned into the pET-28a vector (Novagen). After the recombinant plasmids were verified by sequencing, the plasmid was transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) (Invitrogen), which was grown in LB medium at 37 °C to an OD600 (0.8–1.0) and induced by 0.4 mM isopropyl-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and grown at 20 °C for 16 h. The cell pellet was harvested and re-suspended in 30 mL buffer (20 mM Tris pH 8.5, 200 mM NaCl, and 10 mM imidazole), followed by disruption on a French press. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 21,000 rpm for 30 min. The supernatant was loaded to Ni-agarose affinity resin, which was washed with buffer A containing 20 mM Tris pH 8.5, 200 mM NaCl, and 10 mM imidazole, and eluted with buffer B containing 20 mM Tris, pH 8.5, 250 mM NaCl, and 150 mM imidazole. The protein was further purified with size exclusion chromatography at 20 mM Tris pH 8.5 and 200 mM NaCl.

3.4.2. Enzyme Inhibition Assay

The IMPDH2 inhibitory effects of test compounds were measured using the recombinant protein above. The enzyme solution (20 µL, 10 µg/mL), test compounds (10 µL) and buffer (40 µL, 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.2) were pipetted and mixed in a 96-well microtiter plate. The mixture was incubated for 10 min at 37 °C. After incubation, inosine 5′-monophosphate (IMP) substrate solution (30 µL, 2.5 mM) and NAD+ (30 µL, 5 mM) were added. The reaction can be readily monitored by an increase in optical absorbance at 340 nm. MPA was used as a positive control and averages of three replicates were calculated. The data were imported into Prism (version 5.0, GraphPad) and the IC50 values were calculated by using a standard dose response curve fitting.

3.4.3. Immunosuppressive Activity of Test Compounds

BALB/c mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and the spleens were removed aseptically. Mononuclear cell suspensions were prepared after cell debris, and clumps were removed. Erythrocytes were depleted with ammonium chloride buffer solution. Lymphocytes were washed and suspended in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 mg/mL). The 5 × 105 (150 μL per well) spleen cells in 96-well microtiter plates were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified and 5% CO2-containing incubator for 24 h in the presence or absence of the serious concentrations (ranging from 0.1 to 100 µM) of compounds. The cultures were stimulated with 5 μg/mL of concanavalin A (ConA) to induce T cells proliferative response. After treatment for 24 h, the cell quantity was measured using a CCK8 assay kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

3.5. Molecular Docking Simulation

The virtual docking was implemented in the Surflex-Dock module of the FlexX/Sybyl software, which is a fast docking method that allows sufficient flexibility of ligands and keeps the target protein rigid. Molecules were built with Chemdraw and optimized at molecular mechanical and semiempirical level by using Open Babel GUI. X-ray crystal structure of IMPDH2 at 2.6 Å resolution (PDB ID: 1JR1) was taken from RCSB Protein Data Bank (

www.rcsb.org). The crystallographic ligand was extracted from the active site and the designed ligands were modelled. All the hydrogen atoms were added to define the correct ionization and tautomeric states, and the carboxylate, phosphonate, and sulphonate groups were considered in their charged forms. In the docking calculation, the default FlexX scoring function was used for exhaustive searching, solid body optimizing, and interaction scoring. Finally, the ligands with the lowest-energy and the most favorable orientation were selected.