The Relationship between Survival Sex and Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms in a High Risk Female Population

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Current Study

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Measures

3.1.1. Focal Independent Variables

3.1.2. Dependent Variable

3.1.3. Demographic Variables

3.2. Analytic Approach

4. Results

4.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

4.2. Bivariate Results

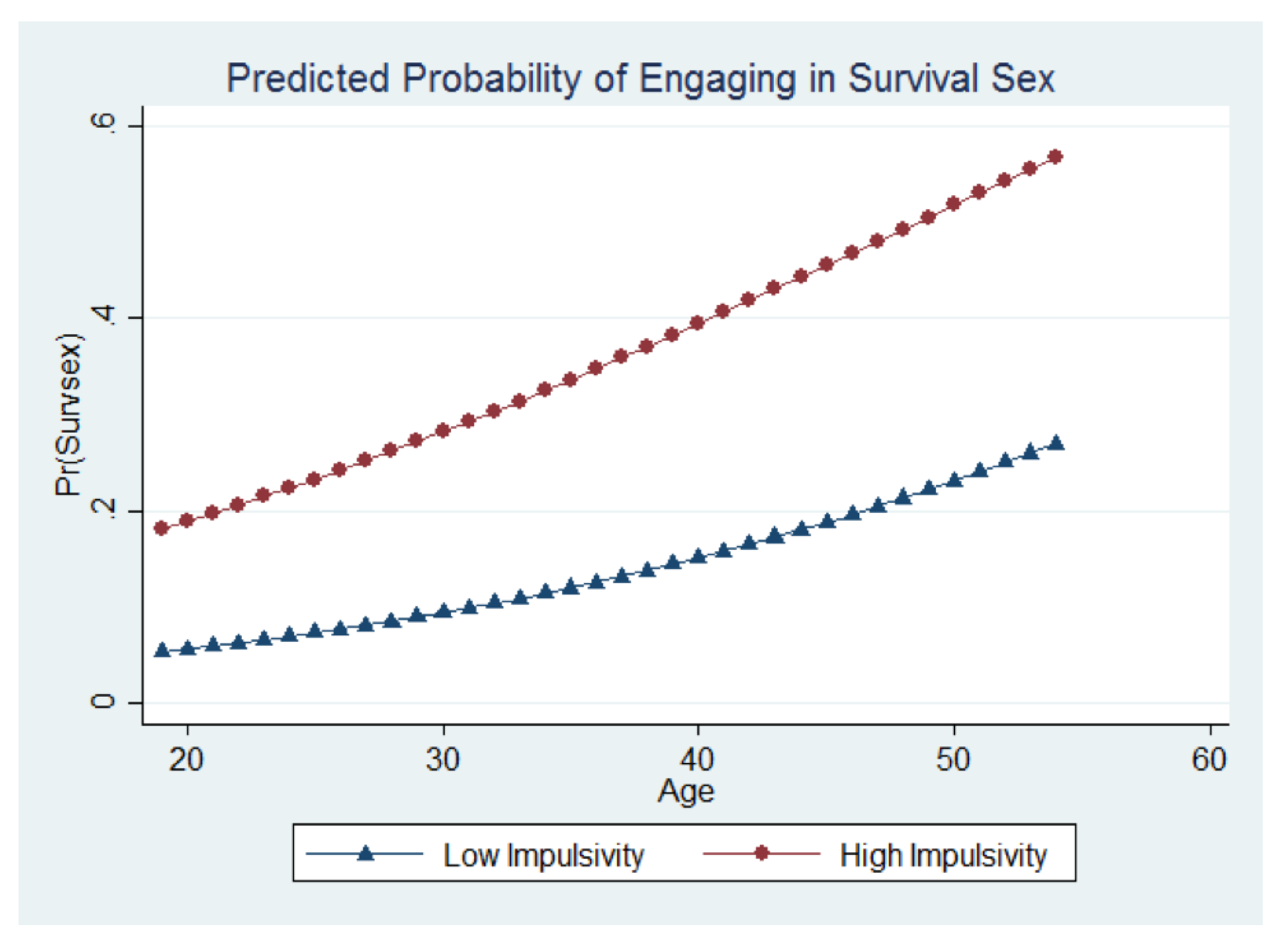

4.3. Multivariate Results

5. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BPD | Borderline Personality Disorder |

References

- Greene, J.M.; Ennett, S.T.; Ringwalt, C.L. Prevalence and correlates of survival sex among runaway and homeless youth. Am. J. Public Health 1999, 89, 1406–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walls, N.E.; Bell, S. Correlates of engaging in survival sex among homeless youth and young adults. J. Sex Res. 2011, 48, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, S.; Camlin, C.; Ennett, S. Substance use and risky sexual behavior among homeless and runaway youth. J. Adolesc. Health 1998, 23, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forst, M.L. Sexual risk profiles of delinquent and homeless youths. J. Community Health 1994, 19, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, B.; Hagan, J. Surviving on the Street The Experiences of Homeless Youth. J. Adolesc. Res. 1992, 7, 412–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.M.; Iritani, B.J.; Hallfors, D.D. Prevalence and correlates of exchanging sex for drugs or money among adolescents in the United States. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2006, 82, 354–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferguson, K.M.; Bender, K.; Thompson, S.J.; Maccio, E.M.; Xie, B.; Pollio, D. Social Control Correlates of Arrest Behavior Among Homeless Youth in Five U.S. Cities. Violence Vict. 2011, 26, 648–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindsey, E.W.; Kurtz, P.D.; Jarvis, S.; Williams, N.R.; Nackerud, L. How runaway and homeless youth navigate troubled waters: Personal strengths and resources. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2000, 17, 115–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoder, K.A.; Whitbeck, L.B.; Hoyt, D.R. Gang involvement and membership among homeless and runaway youth. Youth Soc. 2003, 34, 441–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Bassel, N.; Schilling, R.F.; Irwin, K.L.; Faruque, S.; Gilbert, L.; Von Bargen, J.; Serrano, Y.; Edlin, B.R. Sex trading and psychological distress among women recruited from the streets of Harlem. Am. J. Public Health 1997, 87, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehman, A.F.; Dixon, L.B.; Kernan, E.; DeForge, B.R.; Postrado, L.T. A randomized trial of assertive community treatment for homeless persons with severe mental illness. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1997, 54, 1038–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padgett, D.K.; Gulcur, L.; Tsemberis, S. Housing first services for people who are homeless with co-occurring serious mental illness and substance abuse. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2006, 16, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, R.L.; Whitbeck, L.B. Sexual abuse as a precursor to prostitution and victimization among adolescent and adult homeless women. J. Fam. Issues 1991, 12, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, K.A.; Johnson, K.A. Trading sex: Voluntary or coerced? The experiences of homeless youth. J. Sex Res. 2006, 43, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyler, K.A.; Whitbeck, L.B.; Chen, X.; Johnson, K. Sexual health of homeless youth: Prevalence and correlates of sexually transmissible infections. Sex. Health 2007, 4, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kipke, M.D.; Simon, T.R.; Montgomery, S.B.; Unger, J.B.; Iversen, E.F. Homeless youth and their exposure to and involvement in violence while living on the streets. J. Adolesc. Health 1997, 20, 360–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, G.L.; MacKenzie, R.G.; Pennbridge, J.; Swofford, A. A risk profile comparison of homeless youth involved in prostitution and homeless youth not involved. J. Adolesc. Health 1991, 12, 545–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yates, G.L.; MacKenzie, R.; Pennbridge, J.; Cohen, E. A risk profile comparison of runaway and non-runaway youth. Am. J. Public Health 1988, 78, 820–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagen, J.L. Gender and homelessness. Soc. Work 1987, 32, 312–316. [Google Scholar]

- Opler, L.A.; White, L.; Caton, C.L.; Dominguez, B.; Hirshfield, S.; Shrout, P.E. Gender differences in the relationship of homelessness to symptom severity, substance abuse, and neuroleptic noncompliance in schizophrenia. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2001, 189, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dombrowski, K.; Sittner, K.; Crawford, D.; Welch-Lazoritz, M.; Habecker, P.; Khan, B. Network Approaches to Substance Use and HIV/Hepatitis C Risk among Homeless Youth and Adult Women in the United States: A Review. Health 2016, 8, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tessler, R.; Rosenheck, R.; Gamache, G. Gender differences in self-reported reasons for homelessness. J. Soc. Distress Homeless 2001, 10, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitbeck, L.B.; Simons, R.L. Life on the Streets: The Victimization of Runaway and Homeless Adolescents. Youth Soc. 1990, 22, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauce, A.M.; Paradise, M.; Ginzler, J.A.; Embry, L.; Morgan, C.J.; Lohr, Y.; Theofelis, J. The characteristics and mental health of homeless adolescents age and gender differences. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 2000, 8, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, R.; Terry, K.; Dank, M.; Khan, B.; Dombrowski, K. The CSEC Population in New York City: Size, Characteristics and Needs; National Institute of Justice, United States Department of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Varma, S.; Gillespie, S.; McCracken, C.; Greenbaum, V.J. Characteristics of child commercial sexual exploitation and sex trafficking victims presenting for medical care in the United States. Child Abuse Neglect 2015, 44, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ball, S.A.; Cobb-Richardson, P.; Connolly, A.J.; Bujosa, C.T.; O’Neall, T.W. Substance abuse and personality disorders in homeless drop-in center clients: Symptom severity and psychotherapy retention in a randomized clinical trial. Compr. Psychiatry 2005, 46, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coid, J.; Yang, M.; Bebbington, P.; Moran, P.; Brugha, T.; Jenkins, R.; Farrell, M.; Singleton, N.; Ullrich, S. Borderline personality disorder: Health service use and social functioning among a national household population. Psychol. Med. 2009, 39, 1721–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenzenweger, M.F.; Lane, M.C.; Loranger, A.W.; Kessler, R.C. DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol. Psychiatry 2007, 62, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennay, A.; Cameron, J.; Reichert, T.; Strickland, H.; Lee, N.K.; Hall, K.; Lubman, D.I. A systematic review of interventions for co-occurring substance use disorder and borderline personality disorder. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2011, 41, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hull, J.W.; Clarkin, J.F.; Yeomans, F. Borderline Personality Disorder and Impulsive Sexual Behavior. Psychiatr. Serv. 1993, 44, 1000–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanarini, M.C.; Parachini, E.A.; Frankenburg, F.R.; Holman, J.B.; Hennen, J.; Reich, D.B.; Silk, K.R. Sexual relationship difficulties among borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2003, 191, 479–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunderson, J.G. The borderline patient’s intolerance of aloneness: Insecure attachments and therapist availability. Am. J. Psychiatry 1996, 153, 752–758. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bender, D.S.; Dolan, R.T.; Skodol, A.E.; Sanislow, C.A.; Dyck, I.R.; McGlashan, T.H.; Shea, M.T.; Zanarini, M.C.; Oldham, J.M.; Gunderson, J.G. Treatment utilization by patients with personality disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 2001, 158, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, M.; Mattia, J.I. Differences between clinical and research practices in diagnosing borderline personality disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 1999, 156, 1570–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, C.; Victor, S.E.; Klonsky, E.D. Characterizing positive and negative emotional experiences in young adults with Borderline Personality Disorder symptoms. J. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 72, 956–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieb, K.; Zanarini, M.C.; Schmahl, C.; Linehan, M.M.; Bohus, M. Borderline personality disorder. Lancet 2004, 364, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalichman, S.C.; Gore-Felton, C.; Benotsch, E.; Cage, M.; Rompa, D. Trauma symptoms, sexual behaviors, and substance abuse: Correlates of childhood sexual abuse and HIV risks among men who have sex with men. J. Child Sex. Abuse 2004, 13, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Northey, L.; Dunkley, C.R.; Klonsky, E.D.; Gorzalka, B.B. Borderline personality disorder traits and sexuality: Bridging a gap in the literature. Can. J. Hum. Sex. 2016, 25, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowell, S.E. Biting the hand that feeds: Current opinion on the interpersonal causes, correlates, and consequences of borderline personality disorder. F1000Research 2016, 5, 2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Association, A.P. DSM 5; American Psychiatric Association: Lake St. Louis, MO, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Whitbeck, L.B.; Armenta, B.E.; Welch-Lazoritz, M.L. Borderline personality disorder and Axis I psychiatric and substance use disorders among women experiencing homelessness in three US cities. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidem. 2015, 50, 1285–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christensen, R.C.; Hodgkins, C.C.; Garces, L.; Estlund, K.L.; Miller, M.D.; Touchton, R. Homeless, mentally ill and addicted: The need for abuse and trauma services. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2005, 16, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Percent | Std. Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| Survival Sex | 23.81 | 0.427 |

| Borderline Personality Symptoms | ||

| Anger | 28.89 | 0.455 |

| Mood Shifts | 39.26 | 0.49 |

| Emptiness | 23.88 | 0.428 |

| Identity | 14.18 | 0.35 |

| Dissociative | 15.67 | 0.365 |

| Suicide | 13.43 | 0.342 |

| Abandonment | 20.15 | 0.403 |

| Impulsivity | 29.1 | 0.456 |

| Unstable Relationships | 24.63 | 0.432 |

| White | 43.92 | 0.498 |

| Age (19–54) | 38.89 | 10.18 |

| Education (% with 13+ years) | 58.67 | 0.494 |

| Years Homeless | 4.76 | 4.802 |

| Variable | % Who Engaged in Survival Sex | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anger | Low | 16.48% | 0.003 *** |

| High | 41.67% | ||

| Mood Shifts | Low | 19.74% | 0.208 |

| High | 29.41% | ||

| Emptiness | Low | 22.68% | 0.653 |

| High | 26.67% | ||

| Identity | Low | 20.00% | 0.015 ** |

| High | 41.06% | ||

| Dissociative | Low | 22.22% | 0.376 |

| High | 31.58% | ||

| Suicide | Low | 20.00% | 0.015 ** |

| High | 47.06% | ||

| Abandonment | Low | 19.61% | 0.031 ** |

| High | 40.00% | ||

| Impulsivity | Low | 14.77% | 0.000 *** |

| High | 43.59% | ||

| Unstable Relationships | Low | 21.05% | 0.24 |

| High | 31.25% | ||

| Race | Non-White | 26.83% | 0.273 |

| White | 19.05% | ||

| Education | <12 years | 23.73% | 0.985 |

| 13+ | 23.86% | ||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Survival Sex | ||

| Borderline Personality Symptoms | ||

| Anger | 3.241 | 2.824 |

| Mood Shifts | 0.679 ** | 0.686 |

| Emptiness | 0.322 | 0.246 |

| Identity | 4.845 | 4.959 |

| Dissociative | 0.51 | 0.544 |

| Suicide | 2.113 | 2.748 |

| Abandonment | 1.671 | 1.289 |

| Impulsivity | 3.204 ** | 4.193 ** |

| Unstable Relationships | 0.501 | 0.518 |

| White | 0.612 | |

| Age | 1.059 * | |

| Education | 1.291 | |

| Years Homeless | 1.035 | |

| AIC | 137.4 | 137.3 |

| BIC | 165.8 | 182.4 |

| N | 158 | 158 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ivanich, J.; Welch-Lazoritz, M.; Dombrowski, K. The Relationship between Survival Sex and Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms in a High Risk Female Population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1031. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14091031

Ivanich J, Welch-Lazoritz M, Dombrowski K. The Relationship between Survival Sex and Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms in a High Risk Female Population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2017; 14(9):1031. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14091031

Chicago/Turabian StyleIvanich, Jerreed, Melissa Welch-Lazoritz, and Kirk Dombrowski. 2017. "The Relationship between Survival Sex and Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms in a High Risk Female Population" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 14, no. 9: 1031. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14091031

APA StyleIvanich, J., Welch-Lazoritz, M., & Dombrowski, K. (2017). The Relationship between Survival Sex and Borderline Personality Disorder Symptoms in a High Risk Female Population. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(9), 1031. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14091031