Evaluation of Minimum Unit Pricing of Alcohol: A Mixed Method Natural Experiment in Scotland

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Existing Evidence

1.2. The Purpose of This Evaluation

- Alcoholic drink producers and licence holders;

- The five licensing objectives (covering crime and disorder, public safety, public nuisance, public health, and protecting children and young persons from harm);

- Different groups (defined by age, gender, social and economic deprivation, and levels of alcohol consumption), where possible.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Evaluation Design

- To what extent has MUP contributed to reducing alcohol-related health and social harms in Scotland?

- Are some people and businesses affected (positively and negatively) more than others?

2.2. Study Portfolio

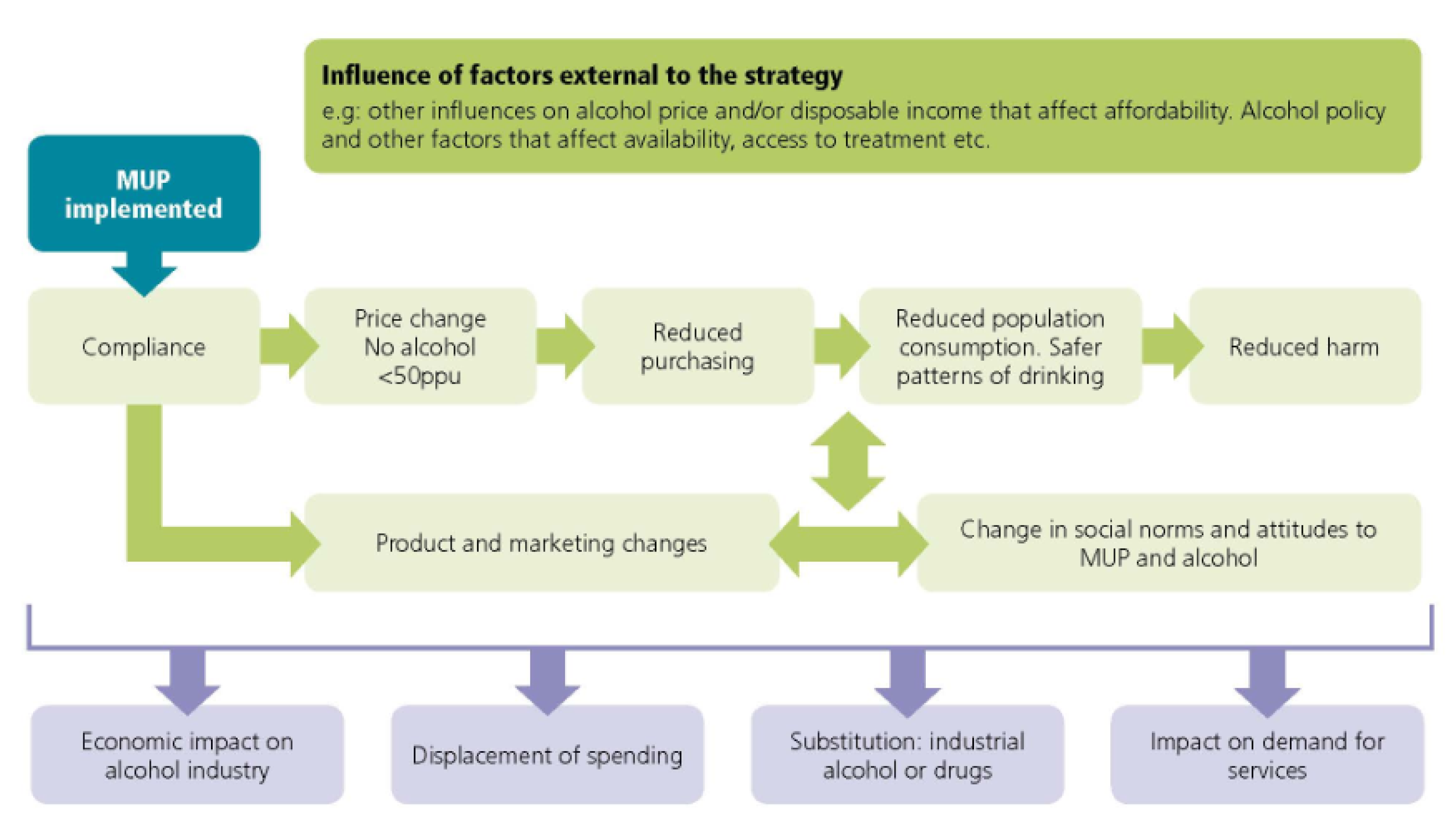

- Compliance, implementation, and attitudes—covering compliance and availability of alcohol <50 ppu. It also includes changes in social norms and attitudes to alcohol and MUP, although these may occur later in response to changes in other outcomes.

- Alcoholic drinks industry—covering price change, change in price distribution, reduced purchasing, product and marketing changes, and economic impact on the alcohol industry.

- Consumption—covering reduced individual and population consumption, and safer patterns of drinking.

- Health and social harms—covering reduced health and social harms, displacement of spending, substitution to non-beverage alcohol or drugs, and the impact on services.

2.3. Setting

2.4. Synthesis Across a Portfolio of Studies

3. Discussion

3.1. Strengths and Limitations

3.2. Governance

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Study | Research Team | Brief Description | Data Period | Study Funder |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MESAS Funded Studies | ||||

| Compliance Final report [31] | NHS Health Scotland | Qualitative study. Interviews with licensing and enforcement to provide an understanding of their experience of compliance with minimum unit pricing (MUP) in licensed premises, and related issues in the first six months of implementation. Descriptive analysis of any quantitative data on non-compliance published. | Aug.–Oct. 2018 | Scottish Government |

| Economic impact on the alcoholic drinks industry in Scotland Interim report [32] | Frontier Economics | Mixed methods study. Quantitative analysis of existing industry survey data to provide an assessment of impact on number of businesses; headcount; turnover; Gross Value Added and value of output, with England and Wales as a control. Post implementation case studies with eight organisations across the industry to provide a qualitative understanding of industry behaviour and impacts. Post implementation interviews with retailers on either side of the Scotland-England border to provide a qualitative understanding of experiences of cross border purchase. | Industry survey data 2011–2019/20 Case studies 2018 and 2021 Interviews 2018–2019 | Scottish Government |

| Small retailers Final report [33] | University of Stirling; University of Sheffield | Mixed methods study with 3 work packages Quantitative analysis of alcohol price data from electronic till receipts Store audit in 20 stores in Central Scotland. Qualitative interview to understand/ explore retailer experiences of MUP and photographic recording to evidence change in alcoholic drink product range and marketing. Documentary analysis of alcohol retail trade press to capture information on changes to pricing, promotions and experiences of MUP pre- and post- implementation. | Price data and documentary analysis: Aug. 2017–Jan. 2019 Store Audit: Oct./Nov. 2017 and Oct./Nov. 2018 | Scottish Government |

| Alcohol price distribution | Public Health Scotland | Quantitative study. Descriptive analysis, with statistical analysis if appropriate, of retail sales data to evaluate the impact of MUP on the volume and proportion of off-trade alcohol (overall and by drink type) sold at different price bands in Scotland, with England and Wales as a control. | April 2015–May 2019 | Scottish Government |

| Alcohol products and prices | Public Health Scotland | Quantitative study. Descriptive analysis, with statistical analysis if appropriate, of retailer and wholesaler data to assess the impact of MUP on the average price, range and volume sales of alcoholic drink products sold in Scotland, with England & Wales as a control. | Retailer data: April 2015–May 2019 Wholesaler: April 2017–May 2019 | Scottish Government |

| Sales-based consumption Interim reports [34,35] | Public Health Scotland | Quantitative study. Descriptive analysis of retail sales data (overall, by trade sector, by drink type). Interrupted time series methods to assess whether the introduction of MUP was associated with a change in the volume of pure alcohol sold in Scotland (overall, by trade sector, and by drink category), with England and Wales as the primary control. | Jan. 2013–April 2021 | Scottish Government |

| Drinking at harmful levels | University of Sheffield, University of Newcastle (Australia) and Figure 8 Consultancy | Mixed methods study with four work packages Survey and in-depth interviews with participants drinking at harmful levels recruited through treatment services to explore the lived experience of MUP and changes in drinking behaviour, substitution to other sources and/or substances, their experience of crime, and the impact on their families. Similar data collected in Northern England for comparison. In-depth interviews with participants drinking at harmful levels recruited through the community to explore the lived experience of MUP and changes in drinking behaviour, substitution to other sources and/or substances, their experience of crime. Interviews with family members of those drinking at harmful levels to understand the lived experience of MUP in families. Quantitative analysis of market research data to assess the impact of MUP on drinking behaviour in the general population in Scotland, with England as a control. Quantitative analysis using linked primary care and hospitalisation/death data to explore the impact of MUP on patients drinking harmfully. It will assess whether there has been a significant change in health outcomes between pre- and post-MUP implementation periods for these patients, looking at all alcohol specific causes (chronic and acute), all alcohol related causes (chronic and acute), and all causes of both hospitalisation and mortality. Several different analytical approaches will be taken, including uncontrolled analyses, analyses using moderate drinkers as a control group and analyses using harmful drinkers in England as a control group. | Data collection in services: Wave 1: Nov. 2017–April 2018 Wave 2: Aug. 2018–Feb. 2019 Wave 3: Nov. 2019–April 2020 Interviews: in the community: Aug. 2017–Sep. 2019 Market research data: Jan. 2009–Dec. 2019 Primary care data: May 2008–Dec. 2019 | Scottish Government |

| Children and young people: own drinking and related behaviour. Final report [36] | Iconic Consulting | Qualitative study Interviews with young people under 18 years and key informants to explore the impact of MUP on their drinking and related behaviour by understanding their lived experience of MUP and the potential mechanisms of change. | Nov. 2018–Mar. 2019 | Scottish Government |

| Hospital admissions and deaths | Public Health Scotland | Quantitative study Interrupted time series methods to assess the impact of MUP on hospital admissions and deaths caused wholly or partially by alcohol in Scotland. Data for England will be explored as the primary geographical control; data for subnational English regions may be used in supplementary analyses. If a suitable geographical control is not available, deaths and admissions not caused by alcohol in Scotland will be used as a non-geographical control. | Jan. 2012–April 2021 | Scottish Government |

| Crime, public safety, and public nuisance | Manchester Metropolitan University | Mixed methods study: Using Police crime and incident data, statistical analysis (interrupted time series analysis, spatio-temporal analysis) and the application of natural experiment methodology. Interviews and focus groups with stakeholders. | 2013–2019 | Scottish Government |

| Children and young people: Harm from others. Final report [37] | Public Health Scotland | Qualitative study. Interviews with practitioners working with children and young people affected by harmful parental/carer alcohol consumption to explore the impact of MUP on protecting children and young people from harms associated with others drinking. | Jan.–Mar. 2019 | Scottish Government |

| Public attitudes to MUP | Data collected by ScotCen, analysed by Public Health Scotland | Quantitative study: Analysis of national survey data to explore whether public attitudes (overall and by population sub-groups) towards MUP change following implementation. | 2013, 2015, and 2019 | Scottish Government |

| Separately-funded studies | ||||

| Consumption and health service impacts of MUP | University of Glasgow, University of Stirling plus others | Mixed methods study with three work packages: Statistical analysis of survey data collected with repeated cross-sectional samples in emergency departments to assess the impact of MUP on the emergency department attendance and prevalence of hazardous and harmful drinking, with data collected in England as a control. Statistical analysis of survey data collected with repeated cross-sectional samples in sexual health clinics to assess the impact of MUP on the other drug use and, source of alcohol and prevalence of hazardous and harmful drinking, with data collected in England as a control. Qualitative longitudinal focus groups with at-risk drinkers and key informant interviews in three communities in Scotland to explore implementation of MUP, responses and attitudes. | Emergency department and sexual health clinics: Feb. 2018, Oct. 2018, and Feb. 2019 Focus groups and interviews: Jan.–April 2018 and Sept.–Nov. 2018 | National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) |

| Self-reported consumption | University of Glasgow | Quantitative study. Analysis of national population survey data, corrected for non-participation bias, to assess the impact of MUP on self-reported consumption. | 1995–2020 | Medial Research Council/Chief Scientist Office |

| Daily survey (N of 1) | University of Glasgow | Mixed methods study. Using N of 1 methodology, daily data collection using a smartphone survey and qualitative interviews conducted by peer researchers to assess the impact of MUP on drinkers recruited through addiction services. | Feb. 2018–Sept. 2019 | Alcohol Change UK |

| Homeless drinkers | Glasgow Caledonian University | Qualitative study. Interviews with homeless drinkers and service providers to explore the impact and lived experiences of MUP among homeless drinkers and street drinkers, and implications for those providing services to these groups. | June 2019–Jan. 2021 | Chief Scientist Office (CSO) |

| Ambulance call-outs | University of Stirling; University of Glasgow; University of Sheffield | Mixed methods study. Statistical analysis of ambulance call out data and qualitative interviews with staff to explore the impact of alcohol and MUP on ambulance call-outs, and the management of alcohol-related call-outs by the Scottish Ambulance Service. | May 2015–Oct. 2020 | Chief Scientist Office (CSO) |

| Prescribing | University of Glasgow | Quantitative study. Statistical analysis of prescribing data to assess the short-term impact of MUP on prescribing for alcohol dependence. | May 2018–May 2019 | Alcohol Change UK |

| Household expenditure | University of Aberdeen | Quantitative study Statistical analysis of household purchasing data 1 year before and after MUP to assess the impact on household expenditure on food, and nutritional quality of family diets, with England as a control. | April 2020–2022 | Chief Scientist Office (CSO) |

References

- Leon, D.; McCambridge, J. Liver cirrhosis mortality rates in Britain from 1950–2002: An analysis of routine data. Lancet 2006, 367, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scottish Government. Changing Scotland’s Relationship with Alcohol: A Framework for Action; Scottish Government: Edinburgh, UK, 2009.

- Giles, L.; Robinson, M. Monitoring and Evaluating Scotland’s Alcohol Strategy: Monitoring Report 2017; NHS Health Scotland: Edinburgh, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, A.; Meier, P.; Stockwell, T.; Sutton, A.; Wilkinson, A.; Wong, R.; Brennan, A.; O’Reilly, D.; Purshouse, R.; Taylor, K. Independent Review of the Effects of Alcohol Pricing and Promotion. Part A: Systematic Reviews; Project Report for the Department of Health, University of Sheffield: Sheffield, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health England. The Public Health Burden of Alcohol and the Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Alcohol Control Policies. An Evidence Review; Public Health England: London, UK, 2016.

- Gillet, C.A. The demand for alcohol: A meta-analysis of elasticities. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2007, 51, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenaar, A.C.; Salois, M.J.; Komro, K.A. Effects of beverage alcohol price and tax levels on drinking: A meta-analysis of 1003 estimates from 112 studies. Addiction 2009, 104, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pryce, R.; Hollingsworth, B.; Walker, I. Alcohol quantity and quality price elasticities: Quantile regression estimates. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2019, 20, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beeston, C.; Craig, N.; Robinson, M.; Burns, J.; Dickie, E.; Ford, J.; Giles, L.; Mellor, R.; McAdams, R.; Shipton, D.; et al. Protocol for the Evaluation of Alcohol Minimum Unit Pricing in Scotland; NHS Health Scotland: Edinburgh, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Angus, C.; Holmes, J.; Pryce, R.; Meier, P.; Brennan, A. Model-Based Appraisal of the Comparative Impact of Minimum Unit Pricing and Taxation Policies in Scotland; ScHARR, University of Sheffield: Sheffield, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Is Alcohol Too Cheap in the UK? The Case for Setting a Minimum Unit Price for Alcohol. Available online: http://www.ias.org.uk/uploads/pdf/News%20stories/iasreport-thomas-stockwell-april2013.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2020).

- Stockwell, T.; Auld, C.; Zhao, J.; Martin, G. Does minimum pricing reduce alcohol consumption? The experience of a Canadian province. Addiction 2012, 107, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockwell, T.; Zhao, J.; Martin, G.; Macdonald, S.; Vallance, K.; Treno, A.; Ponicki, W.; Tu, A.; Buxton, J. Minimum alcohol prices and outlet densities in British Columbia, Canada: Estimated impacts on alcohol-attributable hospital admissions. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, 2014–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Stockwell, T.; Martin, G.; Macdonald, S.; Vallance, K.; Treno, A.; Ponicki, W.R.; Tu, A.; Buxton, J. The relationship between minimum alcohol prices, outlet densities and alcohol-attributable deaths in British Columbia, 2002–2009. Addiction 2013, 108, 1059–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockwell, T.; Zhao, J.; Marzell, M.; Gruenewald, P.J.; Macdonald, S.; Ponicki, W.R.; Martin, G. Relationships between minimum alcohol pricing and crime during the partial privatization of a Canadian government alcohol monopoly. J. Stud. Alcohol. Drugs 2015, 76, 628–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockwell, T.; Zhao, J.; Giesbrecht, N.; Macdonald, S.; Thomas, G.; Wettlaufer, A. The raising of minimum alcohol prices in Saskatchewan, Canada: Impacts on consumption and implications for public health. Am. J. Public Health 2012, 102, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcohol Policy Impact Case Study. The Effects of Alcohol Control Measures on Mortality and Life Expectancy in the Russian Federation. WHO, 2019. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/328167/9789289054379-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Erickson, R.; Stockwell, T.; Pauly, B.; Chow, C.; Roemer, A.; Zhao, J.; Vallance, K.; Wettlaufer, A. How do people with homelessness and alcohol dependence cope when alcohol is unaffordable? A comparison of residents of Canadian-managed alcohol programs and locally recruited controls. Drug Alcohol. Rev. 2018, 37, S174–S183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, H.; Gill, J.; Chick, J. The price of a drink: Levels of consumption and price paid per unit of alcohol by Edinburgh’s ill drinkers with a comparison to wider alcohol sales in Scotland. Addiction 2011, 106, 729–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katikireddi, S.V.; Whitley, E.; Lewsey, J.; Gray, L.; Leyland, A.H. Socioeconomic status as an effect modifier of alcohol consumption and harm: Analysis of linked cohort data. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2, e267–e276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcohol (Minimum Pricing) (Scotland) Act 2012. Available online: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2012/4/contents/enacted (accessed on 13 April 2020).

- Judgement. Scotch Whisky Association and others (Appellants) v The Lord Advocate and another (Respondents) (Scotland). Available online: https://www.supremecourt.uk/cases/docs/uksc-2017-0025-judgment.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2020).

- Craig, P.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Leyland, A.; Popham, F. Natural Experiments: An overview of methods, approaches and contributions to public health research. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2017, 38, 39–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, P.; Dieppe, P.; Macintyre, S.; Michie, S.; Nazareth, I.; Petticrew, M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medial research Council guidance. BMJ 2008, 337, a1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Evaluation of Minimum Unit Pricing. Available online: http://www.healthscotland.scot/health-topics/alcohol/evaluation-of-minimum-unit-pricing-mup (accessed on 13 April 2020).

- Katikireddi, S.V.; Beeston, C.; Millard, A.; Forsyth, R.; Deluca, P.; Drummond, C.; Eadie, D.; Graham, L.; Hilton, S.; Ludbrook, A.; et al. Evaluating possible intended and unintended consequences of the implementation of alcohol minimum unit pricing (MUP) in Scotland: A natural experiment protocol. BMJ 2019, 9, e028482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett-Page, E.; Thomas, J. Methods for the Synthesis of Qualitative Research: A Critical Review. ESRC National Centre for Research Methods. NCRM Working Paper Series, Number (01/09) 2. 2009. Available online: http://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/690/ (accessed on 13 April 2020).

- Threlfall, A.G.; Meah, S.; Fischer, A.J.; Cookson, R.; Rutter, H.; Kelly, M. The appraisal of public health interventions: The use of theory. J. Public Health 2014, 37, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health Research. Cost-Consequences Analysis: An Underused Method of Economic Evaluation. 2019. Available online: https://www.rds-london.nihr.ac.uk/wpcms/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Cost-consequences-analysis_economic-evaluation-updated-22-Feb-2019.doc (accessed on 13 April 2020).

- Douglas, M.; Katikireddi, S.V.; Talbut, M.; McCartney, G. Mitigating the wider health effects of covid-19 pandemic responses. BMJ 2020, 399, m1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickie, E.; Mellor, R.; Myers, F.; Beeston, C. Minimum Unit Pricing (MUP) Evaluation: Compliance (Licensing) Study; NHS Health Scotland: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2019; Available online: http://www.healthscotland.scot/publications/minimum-unit-pricing-evaluation-compliance-study (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Frontier Economics. Minimum Unit Alcohol Pricing: Evaluating the Impacts on the Alcoholic Drinks Industry in Scotland: Baseline Evidence and Initial Impacts; Frontier Economics: London, UK, 2019; Available online: http://www.healthscotland.scot/media/2810/frontier-economics-mup-evaluating-the-impacts-on-the-alcoholic-drinks-industry-in-scotland.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Stead, M.; Critchlow, N.; Eadie, D.; Fitzgerald, N.; Angus, K.; Purves, R.; McKell, J.; MacKintosh, A.M.; Mitchell, H.; Sumpter, C. Evaluating the Impact of Alcohol Minimum Unit Pricing in Scotland: Observational Study of Small Retailers; University of Stirling: Stirling, UK, 2020; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, L.; Robinson, M.; Beeston, C. Minimum Unit Pricing (MUP) Evaluation. In Sales-Based Consumption: A Descriptive Analysis of One Year Post-MUP off-Trade Alcohol Sales Data; NHS Health Scotland: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2020; Available online: http://www.healthscotland.scot/publications/evaluating-the-impact-of-minimum-unit-pricing-mup-on-sales-based-consumption-in-scotland-a-descriptive-analysis-of-one-year-post-mup-off-trade-alcohol-sales-data (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Robinson, M.; Mackay, D.; Giles, L.; Lewsey, J.; Beeston, C. Evaluating the Impact of Minimum Unit Pricing (MUP) on Sales-Based Consumption in Scotland: Controlled Interrupted Time Series Analysis; Public Health Scotland: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2020; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Iconic Consulting. Minimum Unit Pricing in Scotland a Qualitative Study of Children and Young People’s Own Drinking and Related Behaviour. Edinburgh. 2020. Available online: http://www.healthscotland.scot/media/2947/iconic-mup-cyp-own-drinking-and-related-behaviour-english-jan2020.pdf (accessed on 6 May 2020).

- Ford, J.; Myers, F.; Burns, J.; Beeston, C. The Impact of MUP on Protecting Children and Young People from Parents’ and Carers’ Harmful Alcohol Consumption: A Study of Practitioners’ Views; Public Health Scotland: Edinburgh, Scotland, 2020; in press. [Google Scholar]

| Compliance, Implementation + Attitudes | Alcohol Industry | Consumption | Health and Social Harms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MESAS Funded Studies | ||||

| Compliance | √ | |||

| Economic impact | √ | |||

| Small retailers | √ | √ | ||

| Price distribution | √ | √ | ||

| Products and prices | √ | |||

| Sales-based consumption | √ | √ | ||

| Harmful drinking | √ | √ | √ | |

| Children and young people: Own drinking | √ | √ | √ | |

| Health harms | √ | |||

| Crime, public safety and public nuisance | √ | |||

| Children + young people: Harm from others | √ | |||

| Public Attitudes | √ | |||

| Separately-funded studies | ||||

| Consumption and health service impacts of MUP | √ | √ | √ | |

| Self-reported consumption | √ | √ | ||

| Daily survey | √ | √ | √ | |

| Homeless drinkers | √ | √ | √ | |

| Ambulance call-outs | √ | |||

| Prescribing | √ | |||

| Household expenditure | √ | |||

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Beeston, C.; Robinson, M.; Giles, L.; Dickie, E.; Ford, J.; MacPherson, M.; McAdams, R.; Mellor, R.; Shipton, D.; Craig, N. Evaluation of Minimum Unit Pricing of Alcohol: A Mixed Method Natural Experiment in Scotland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3394. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103394

Beeston C, Robinson M, Giles L, Dickie E, Ford J, MacPherson M, McAdams R, Mellor R, Shipton D, Craig N. Evaluation of Minimum Unit Pricing of Alcohol: A Mixed Method Natural Experiment in Scotland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(10):3394. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103394

Chicago/Turabian StyleBeeston, Clare, Mark Robinson, Lucie Giles, Elinor Dickie, Jane Ford, Megan MacPherson, Rachel McAdams, Ruth Mellor, Deborah Shipton, and Neil Craig. 2020. "Evaluation of Minimum Unit Pricing of Alcohol: A Mixed Method Natural Experiment in Scotland" International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 10: 3394. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103394

APA StyleBeeston, C., Robinson, M., Giles, L., Dickie, E., Ford, J., MacPherson, M., McAdams, R., Mellor, R., Shipton, D., & Craig, N. (2020). Evaluation of Minimum Unit Pricing of Alcohol: A Mixed Method Natural Experiment in Scotland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(10), 3394. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17103394