Computational Analysis of the Properties of Post-Keynesian Endogenous Money Systems

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

- Bank sector:

- Supply money on demand through private loans, thereby increasing the money stock;

- Demand the payback of outstanding private loans on predefined intervals, thereby decreasing the money stock.

- Private sector:

- Initiate the money supply through private loan demands;

- Pay off outstanding private debts on predefined intervals.

2.1. Money Creation Through Loans

- Step 1: A loan demand is initiated by the private sector;

- Step 2: The bank sector issues the loan, resulting in the following changes to the bank’s and the private sector’s balance sheets:

| Assets | Liabilities |

| + Private debt | + Deposits |

| Assets | Liabilities |

| + Deposits | + Private debt |

2.2. Money Destruction Through Down Payments

| Assets | Liabilities |

| − Private debt (loan instalment) | − Deposits (loan instalment) |

| − Deposits (interest) | |

| + Equity (interest) |

| Assets | Liabilities |

| − Deposits (loan instalment) | − Private debt (loan instalment) |

| − Deposits (interest) | − Equity (interest) |

2.3. Bank Costs

| Assets | Liabilities |

| + Deposits (bank costs) | |

| − Equity (bank costs) |

| Assets | Liabilities |

| + Deposits (bank costs) | + Equity (bank costs) |

2.4. Profit Retention

3. Model Description

- Growth mode:

- -

- g: growth rate of the money stock;

- Loan demand mode:

- -

- : loan ratio expressed as a percentage of the current money stock;

- Both modes:

- -

- C: number of cycles. Each cycle is interpreted as one year;

- -

- The initial state of all balance sheets;

- -

- Parameters for the bank sector:

- ∗

- m: loan maturity;

- ∗

- p: profit retention ratio on debt.

- t: cycle number;

- : money stock;

- : private debt held by the bank;

- = : debt ratio;

- : size of the loan demand;

- : instalment due.

4. Simulations

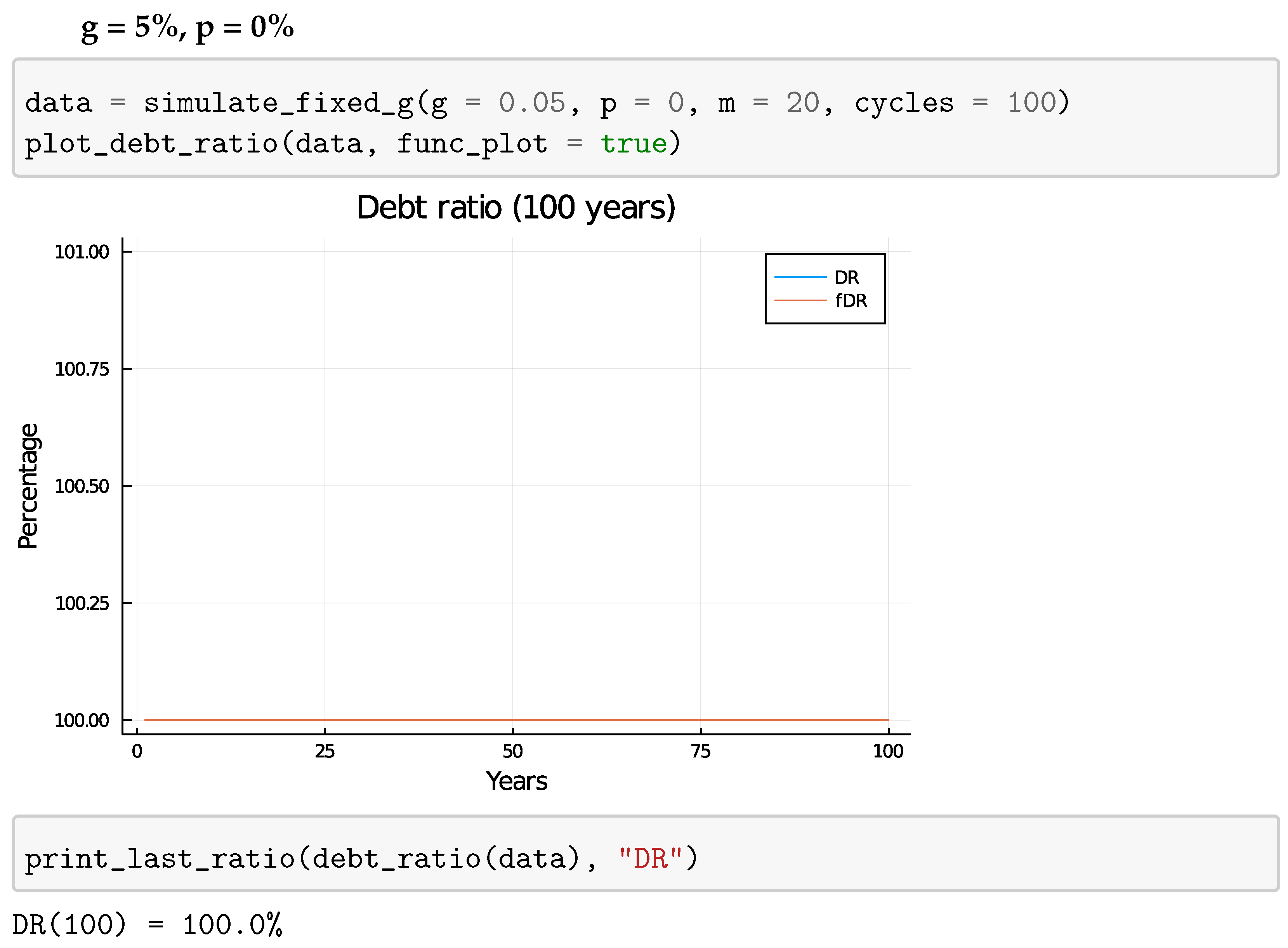

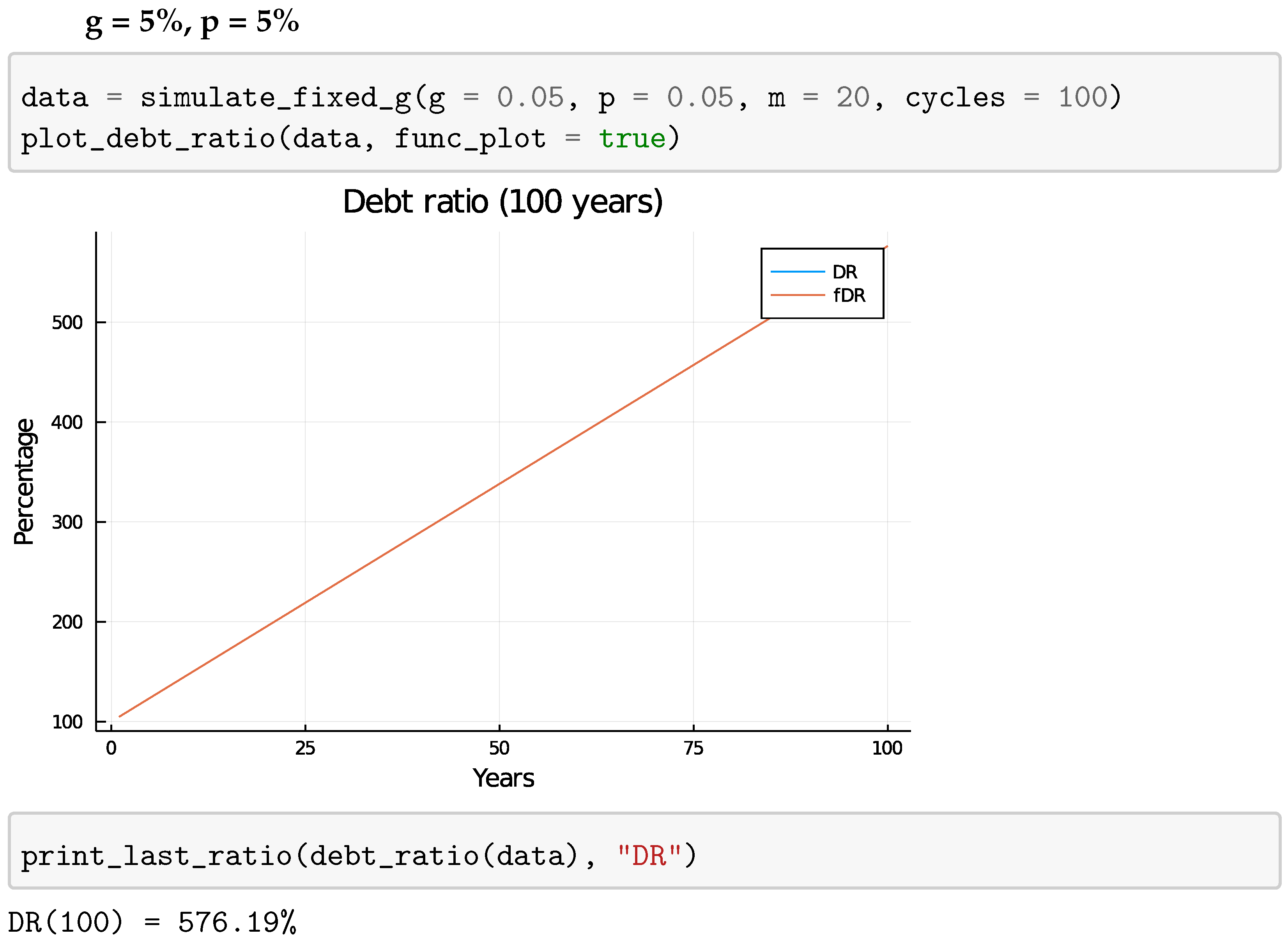

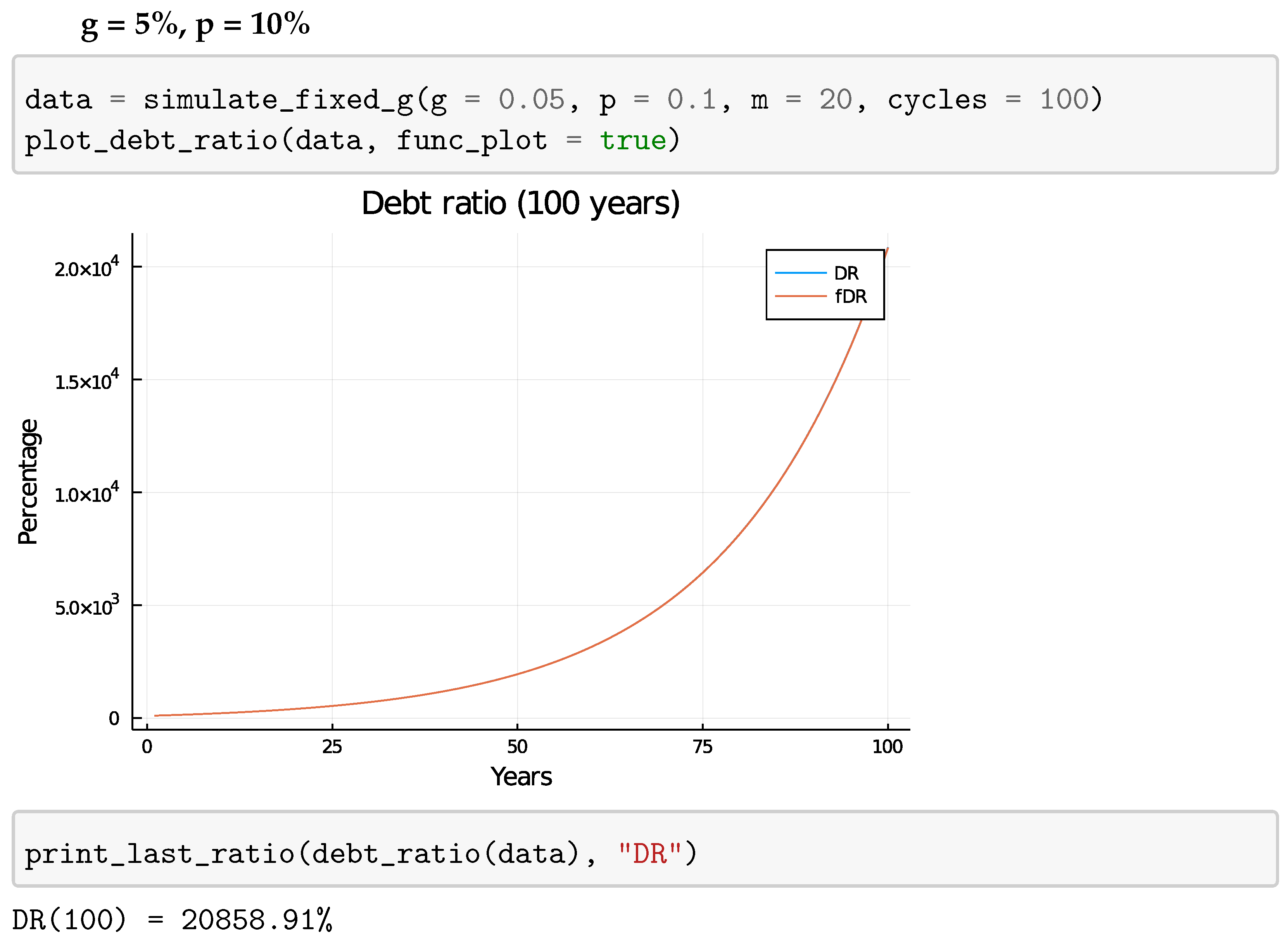

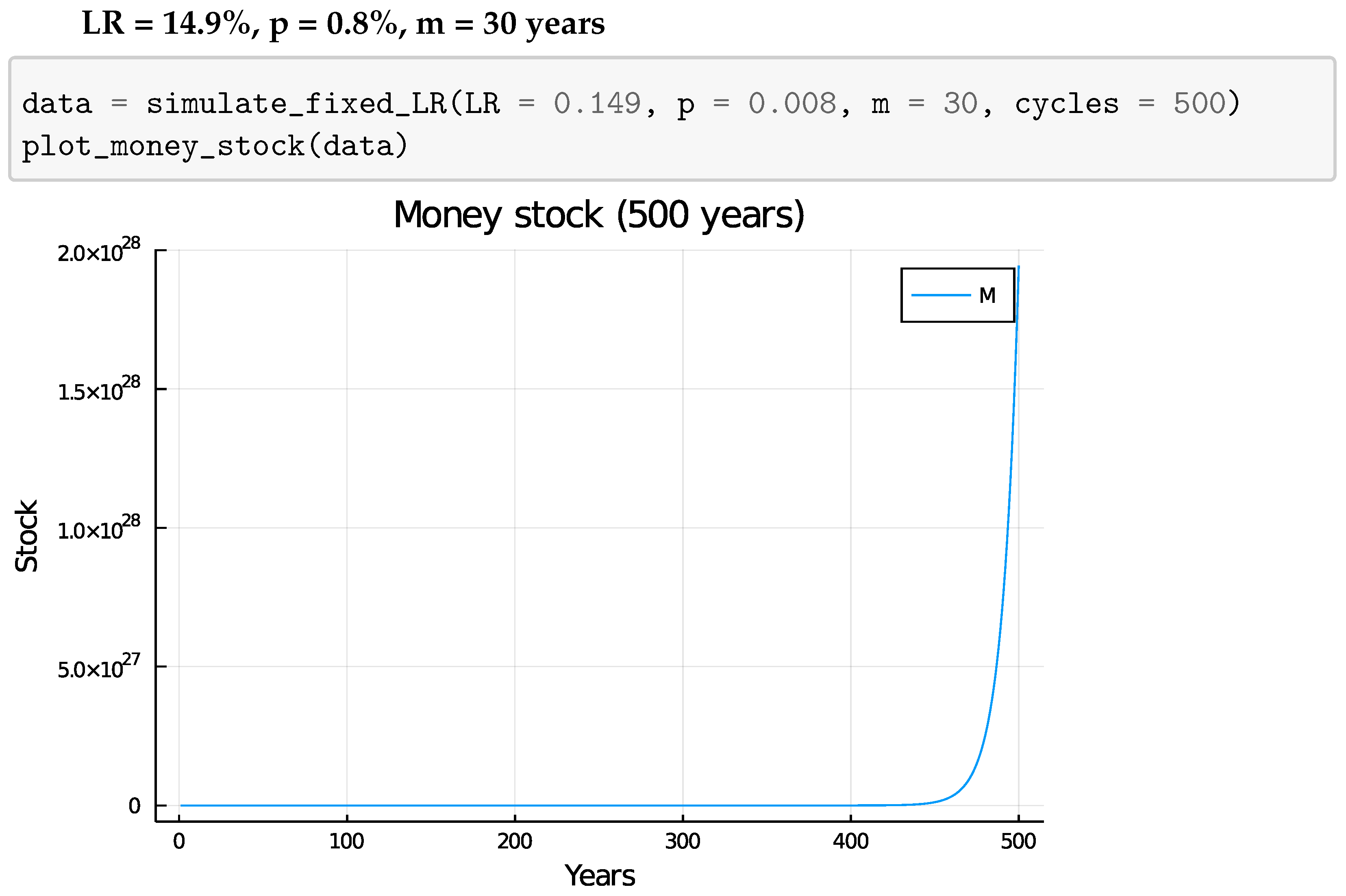

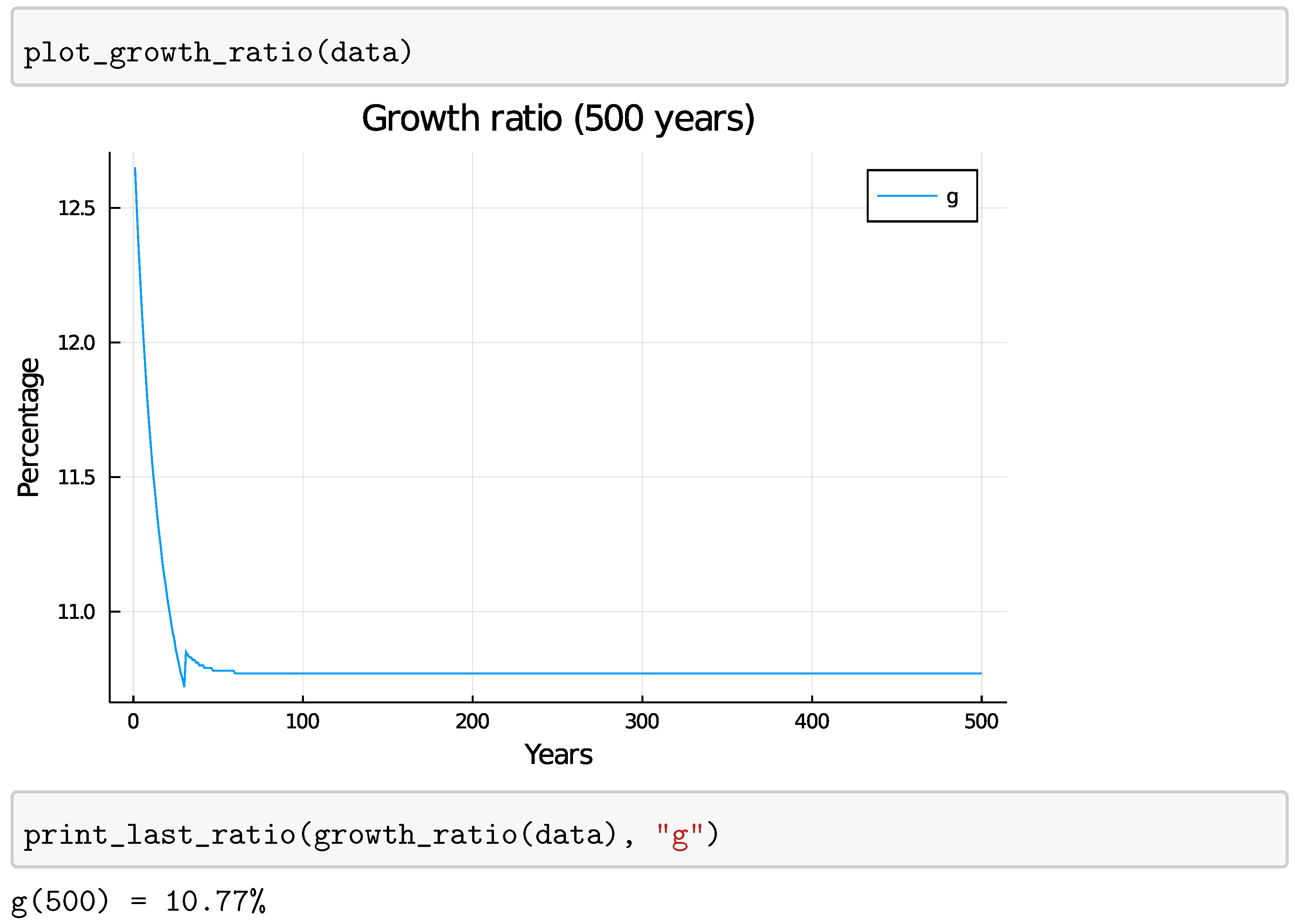

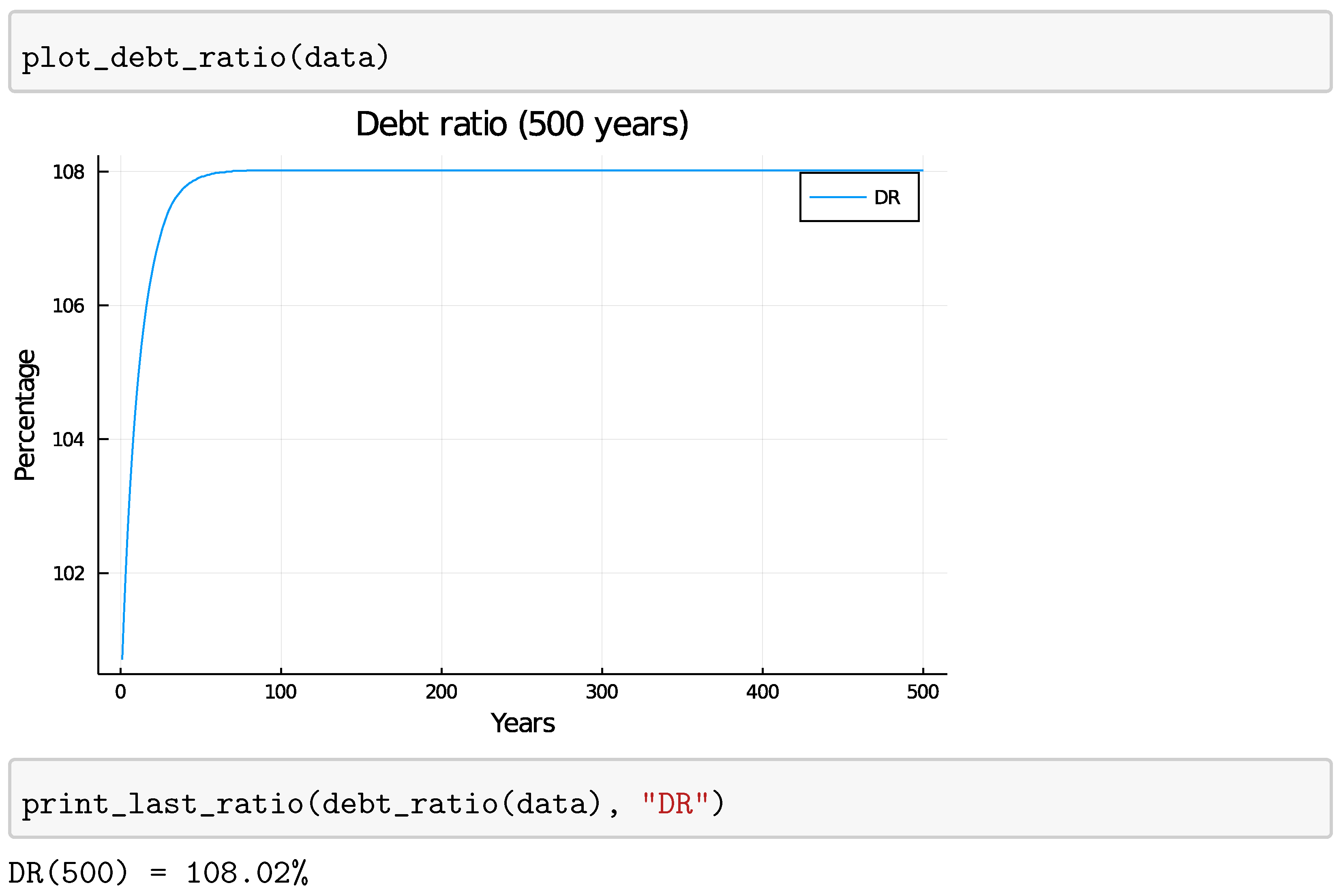

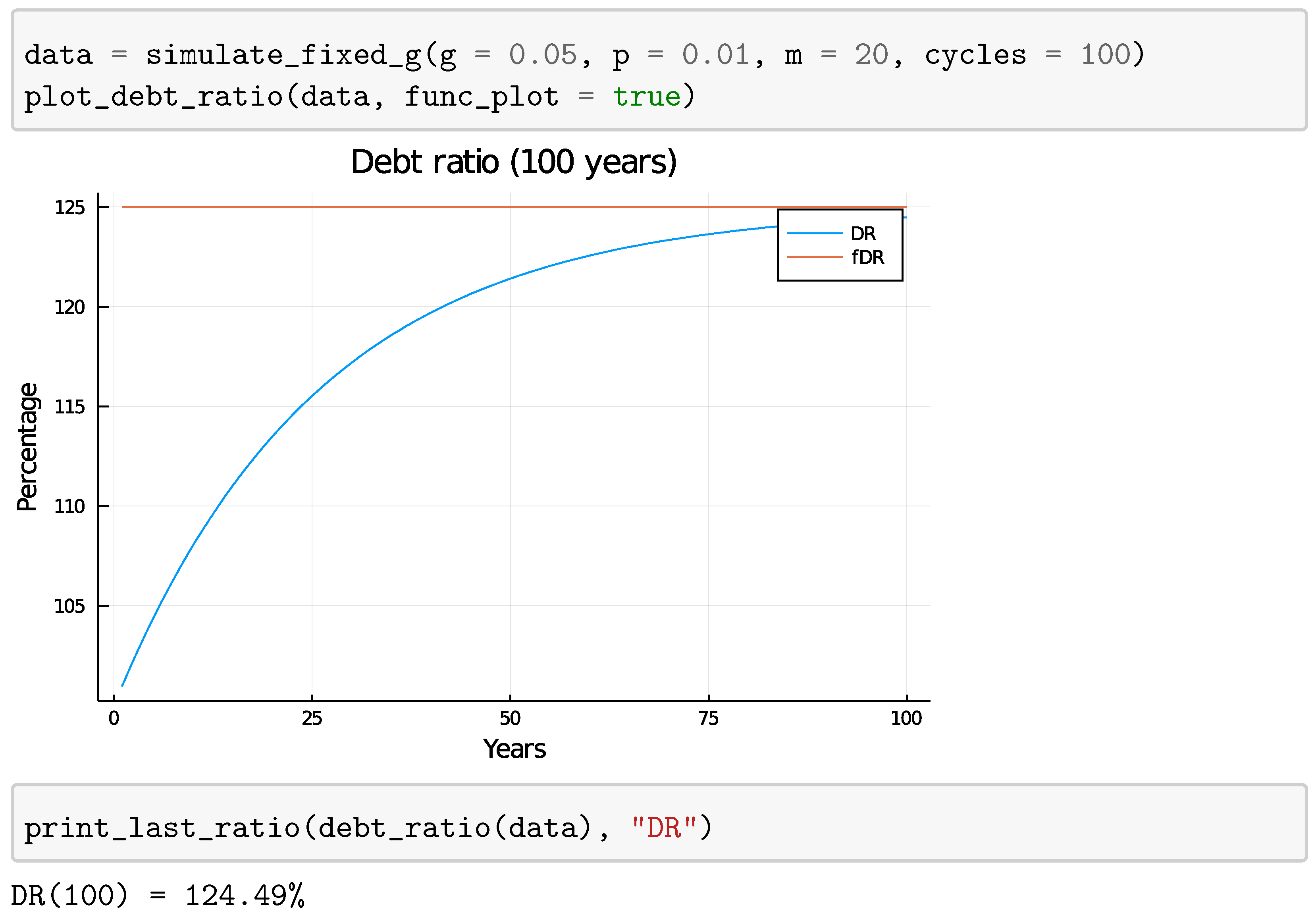

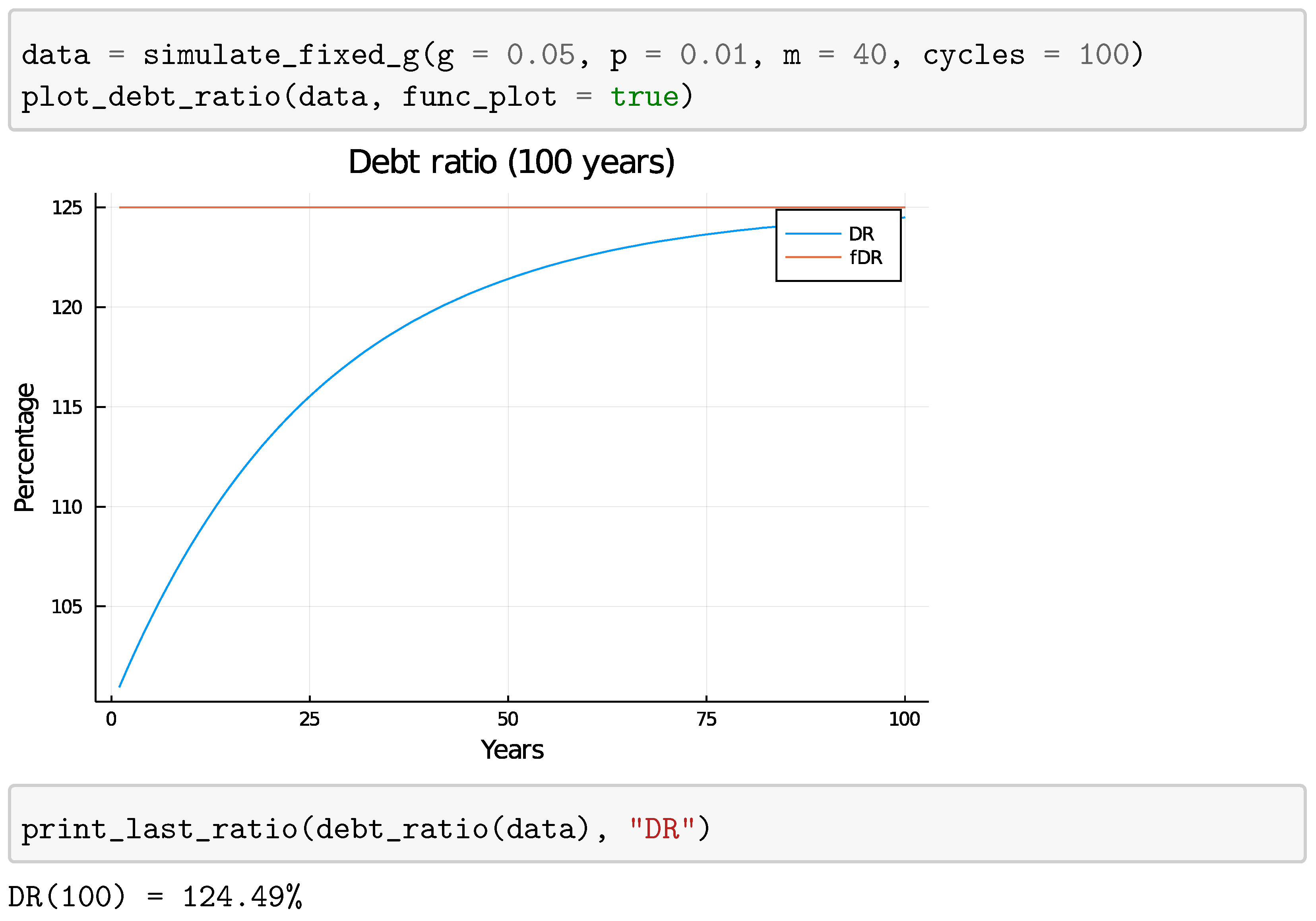

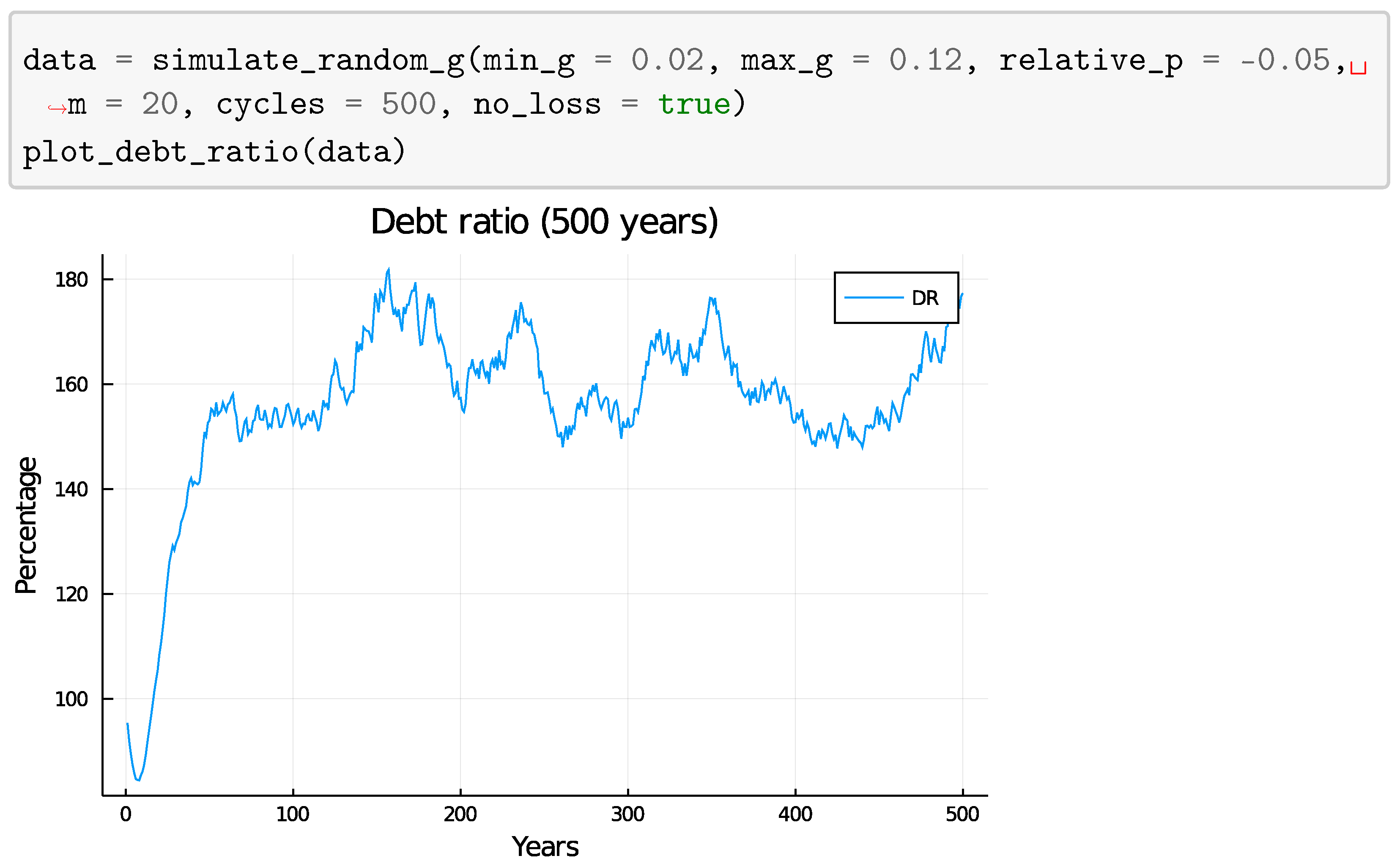

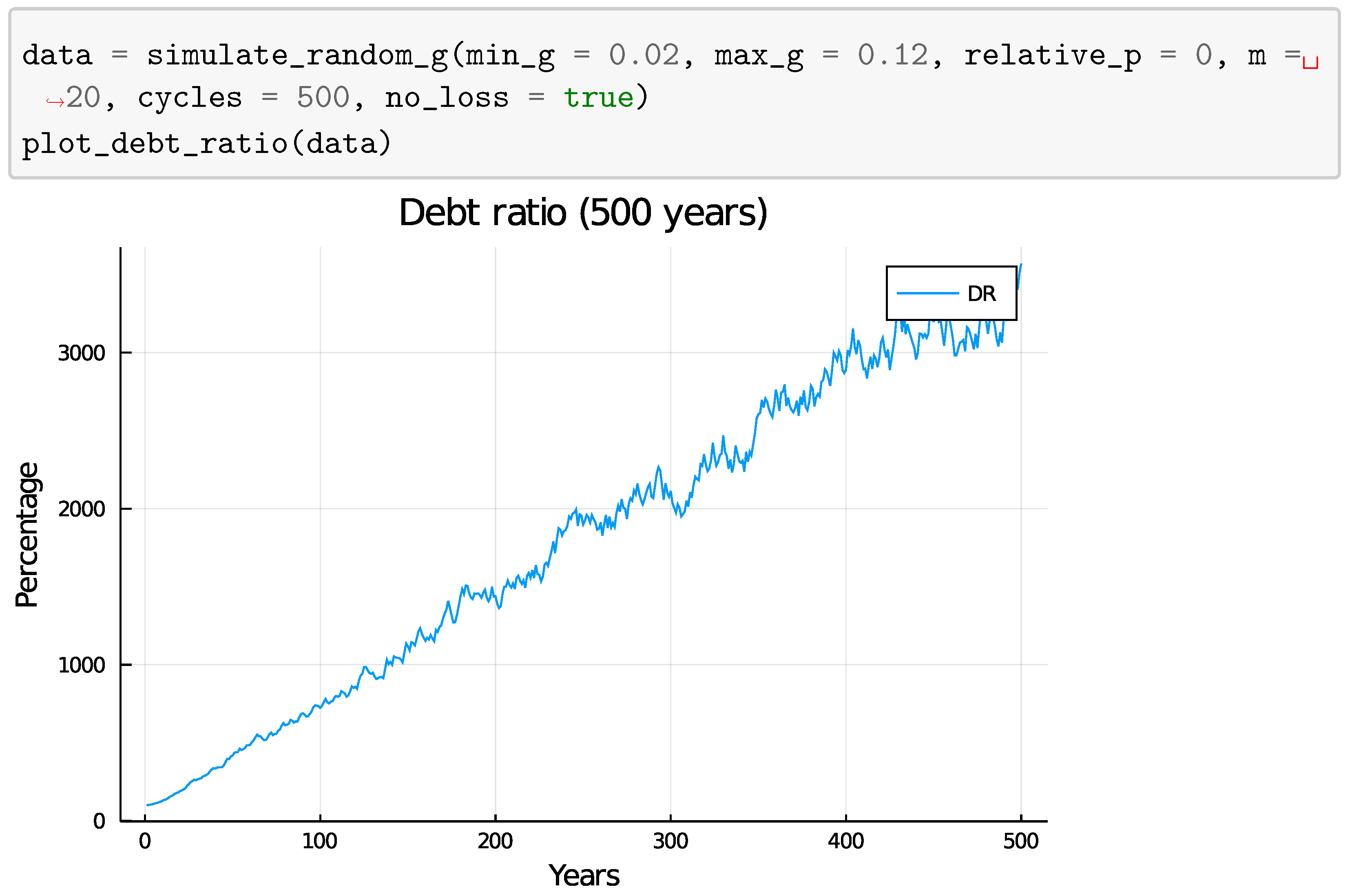

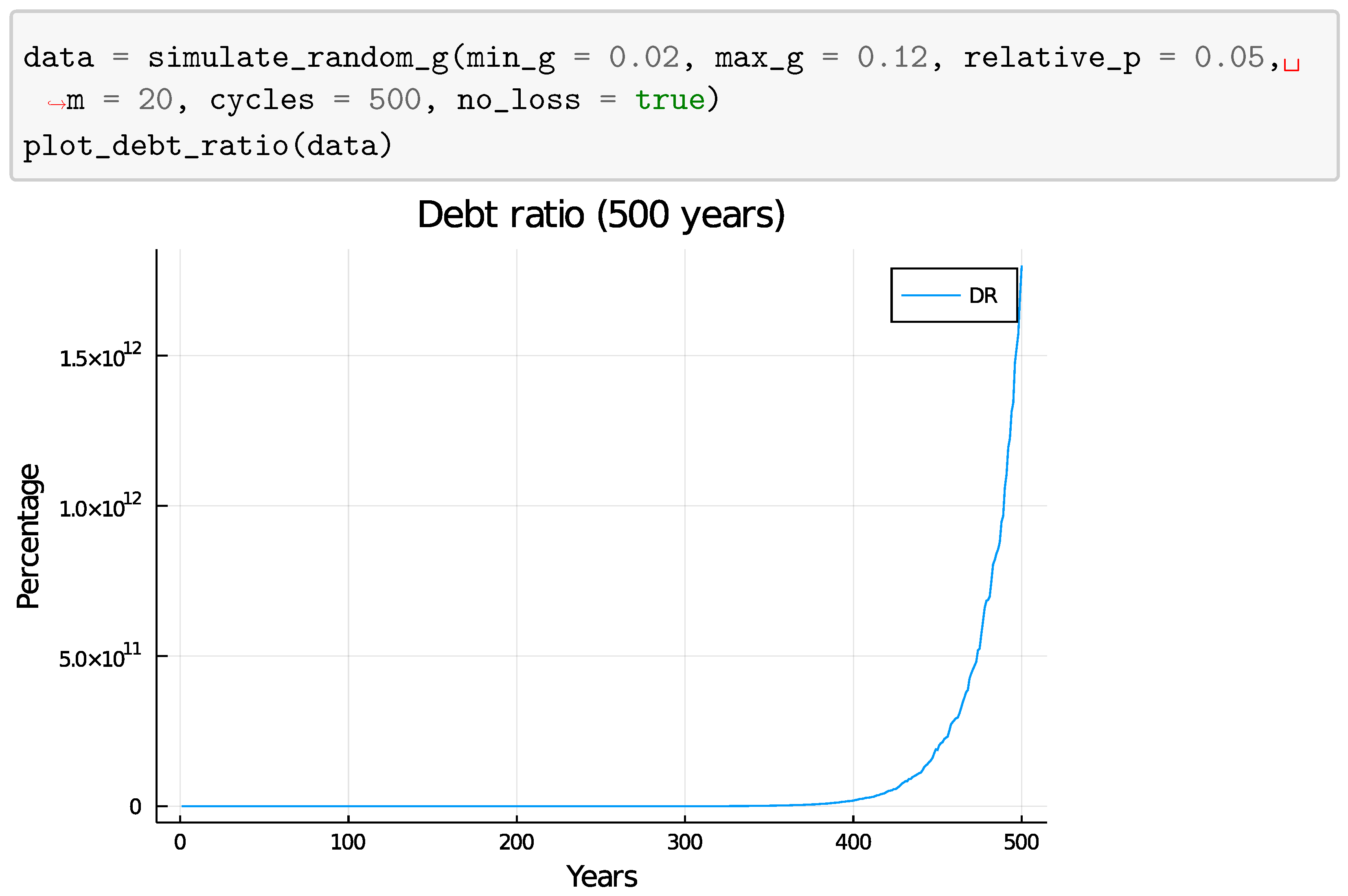

4.1. Fixed Growth Rate

4.1.1. Mathematical Analysis

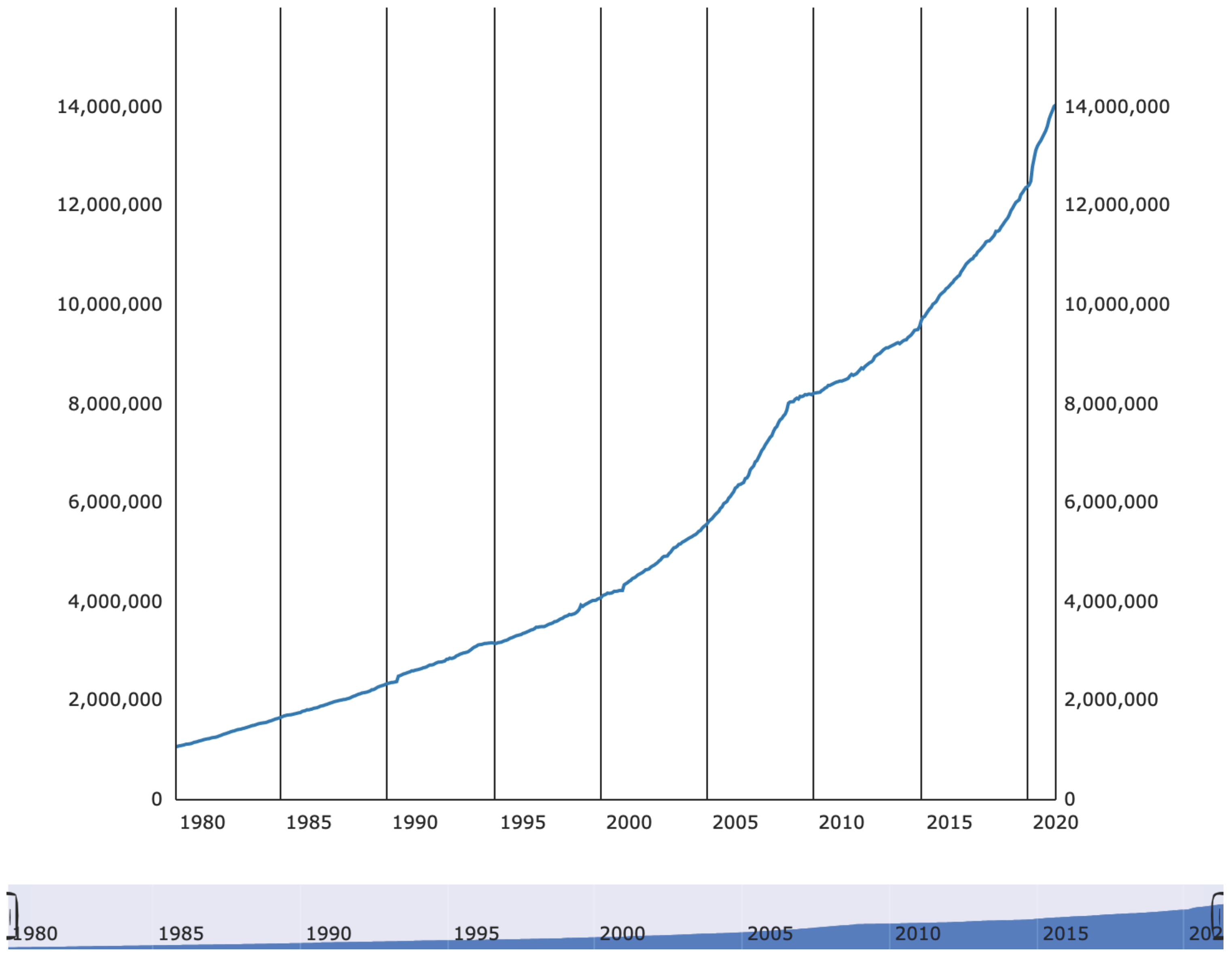

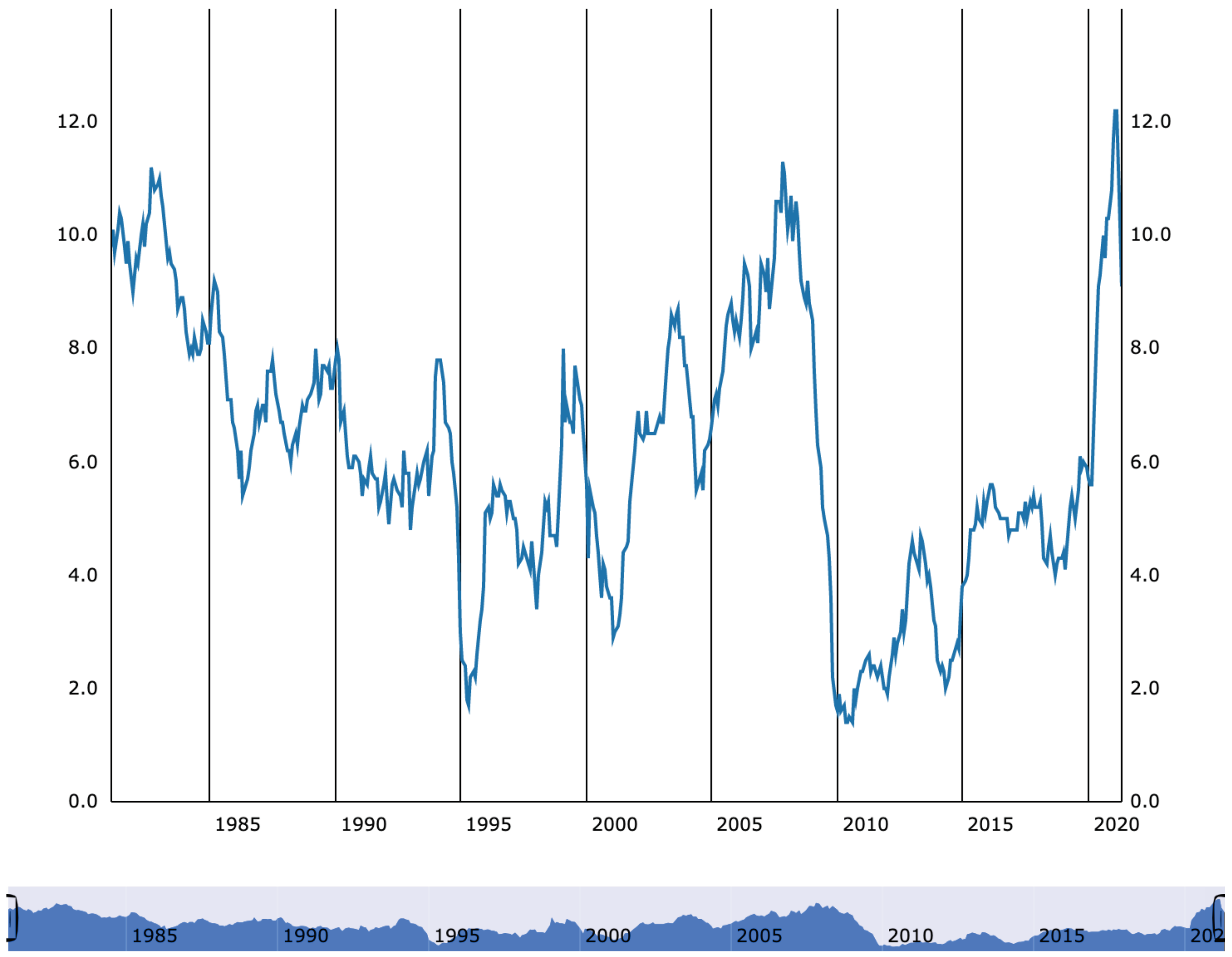

4.1.2. Plots

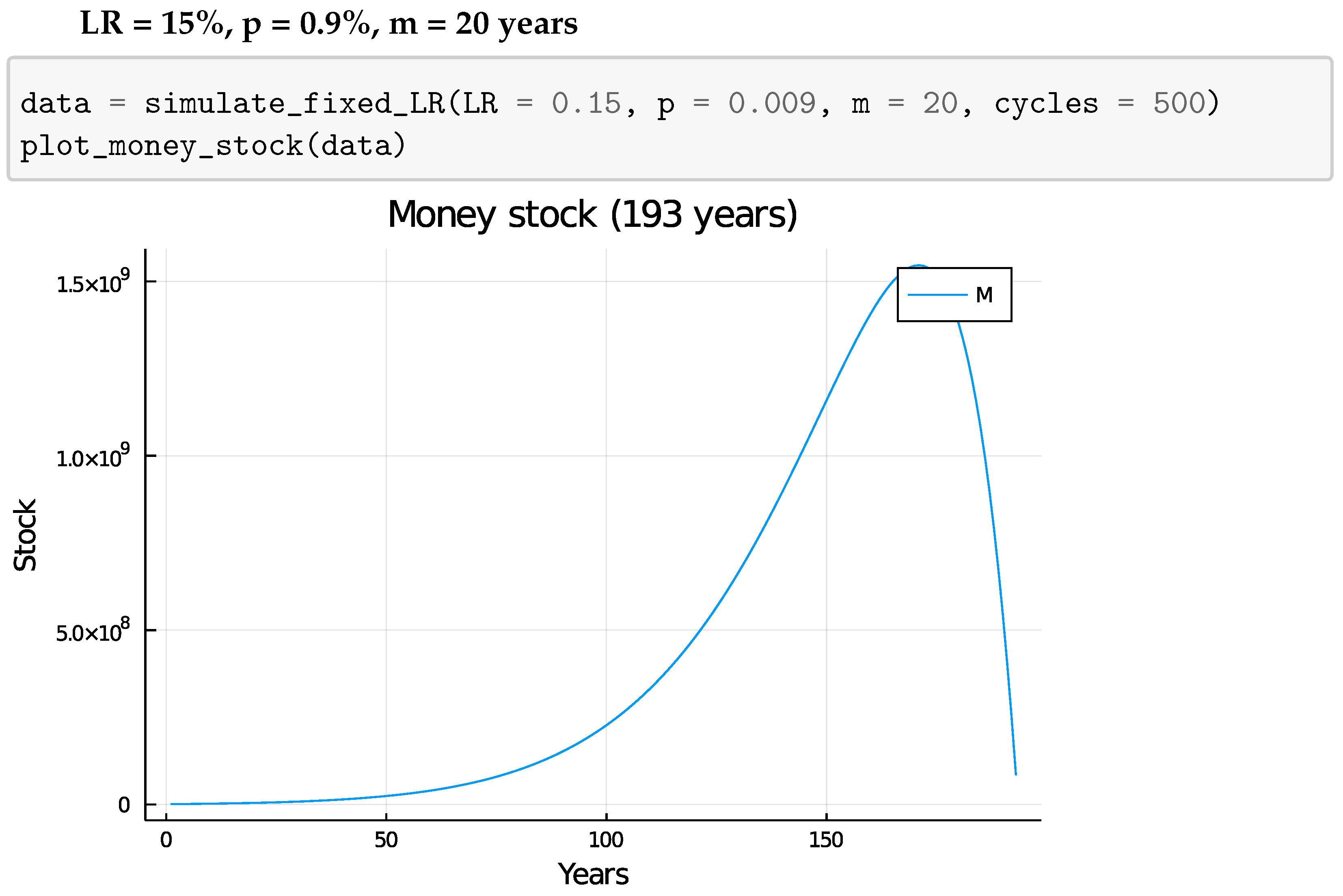

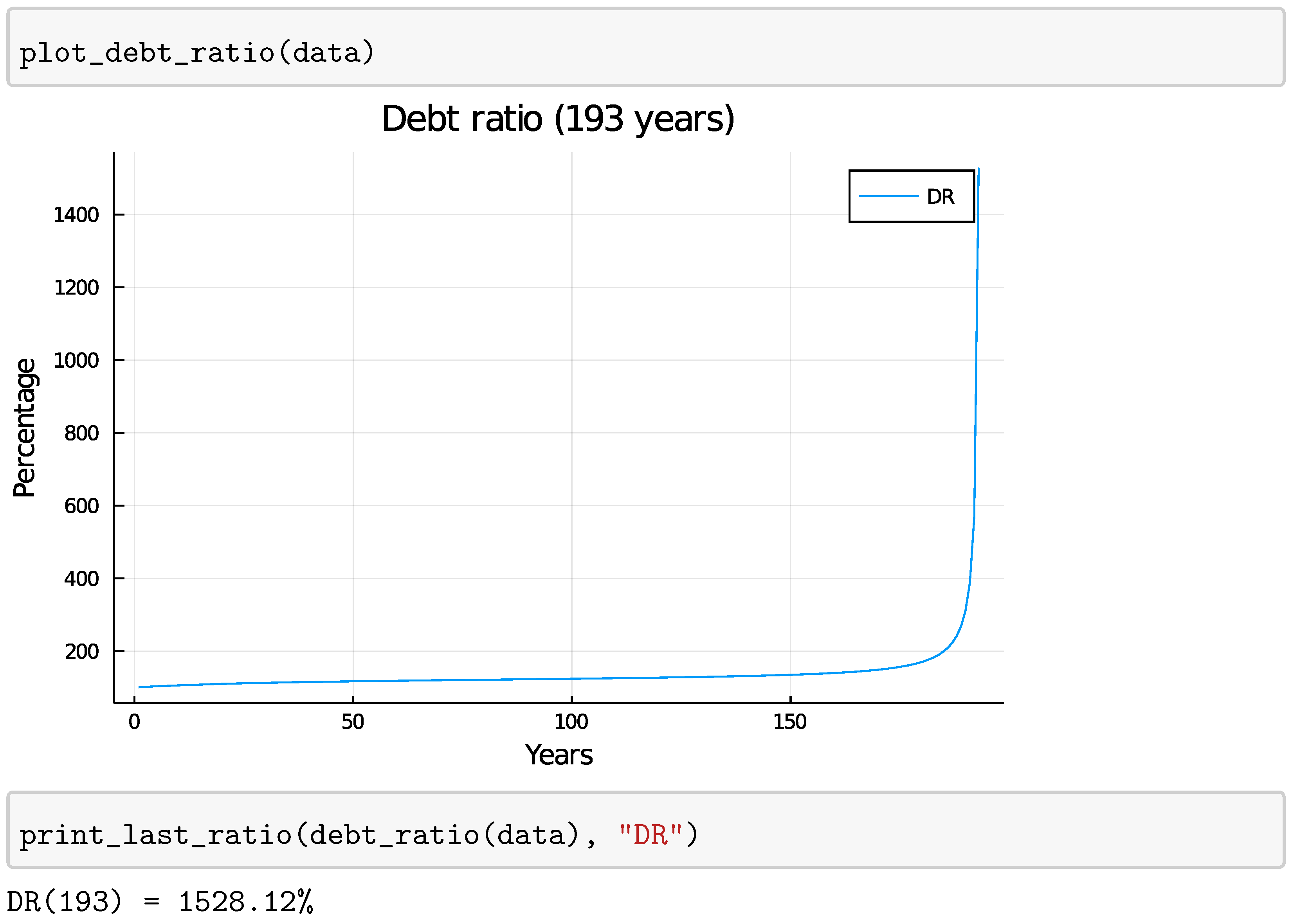

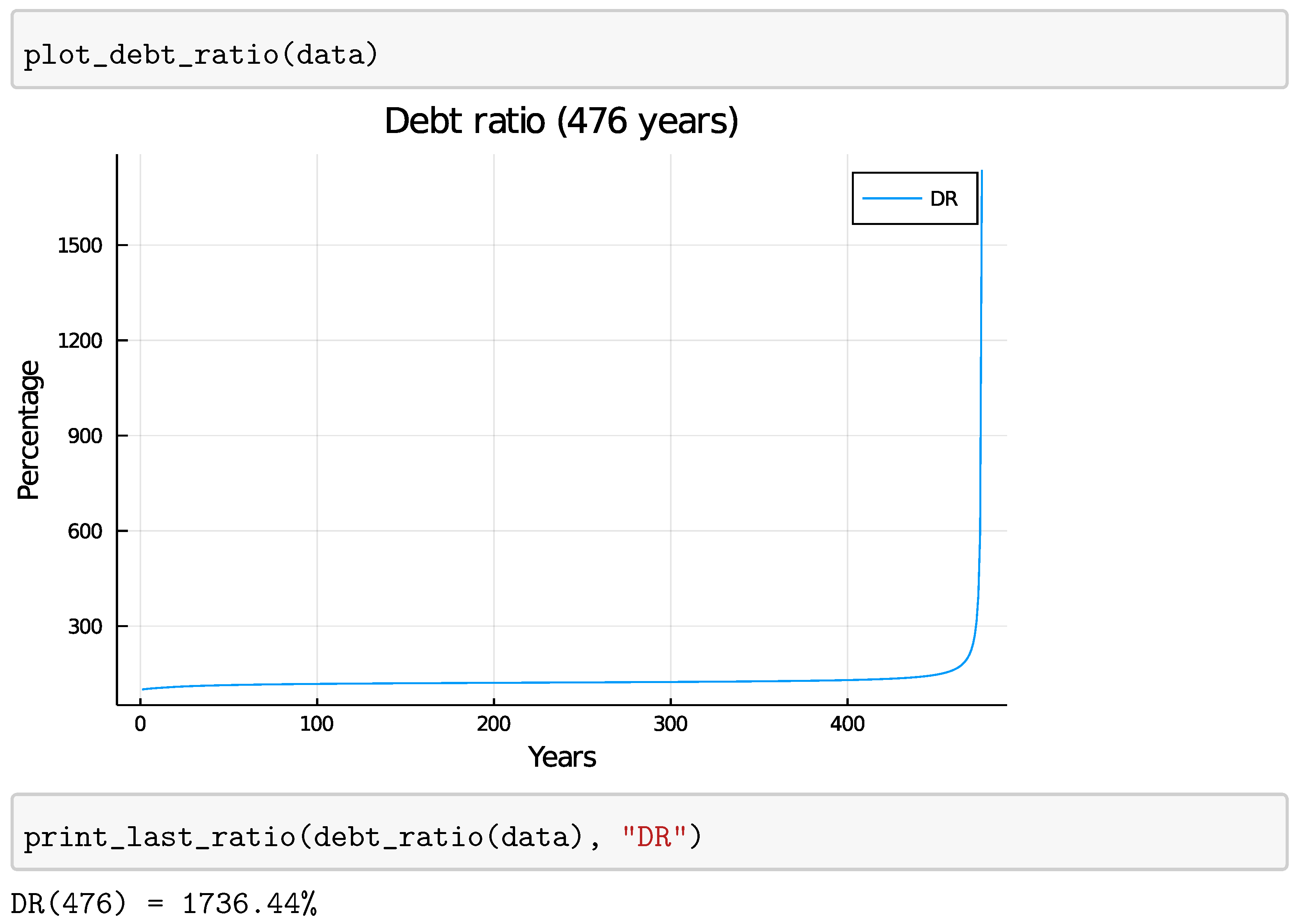

4.2. Fixed Loan Ratio

5. Discussion

5.1. Observations

5.1.1. Fixed Growth Rate

5.1.2. Fixed Loan Ratio

5.2. Steady-State Economy

5.3. Green Economy

5.4. Inflation/Deflation

5.5. Model Limitations

5.5.1. Quantitative Easing

5.5.2. Government Spending

5.5.3. Banks Selling Debt at a Loss

| Assets | Liabilities |

| Private debt = 100,000 | Deposits = 80,000 |

| Equity = 20,000 |

| Assets | Liabilities |

| Deposits = 80,000 | Private debt to bank = 100,000 |

| Equity = −20,000 |

| Assets | Liabilities |

| Private debt = 80,000 | Deposits = 65,000 |

| Equity = 15,000 |

| Assets | Liabilities |

| Deposits = 65,000 | Private debt to bank = 80,000 |

| Security = 20,000 | Private debt to investor = 20,000 |

| Equity = −15,000 |

5.5.4. Loan Defaulting

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Source Code

| 1 | Eurostat website: https://sdw.ecb.europa.eu (accessed on 13 June 2021). |

| 2 | Since cash is not used in the model, M2 is not exactly the same as M, but it is the closest real-world measurement to it. |

| 3 | https://www.degrowth.info/en/ (accessed on 13 July 2021). https://degrowth.org (accessed on 13 July 2021). |

| 4 | UN Meeting Coverage. Only 11 Years Left to Prevent Irreversible Damage from Climate Change, Speakers Warn during General Assembly High-Level Meeting. https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/ga12131.doc.htm (accessed on 13 July 2021). |

References

- Arnsperger, Christian, Jem Bendell, and Matthew Slater. 2021. Monetary Adaptation to Planetary Emergency: Addressing the Monetary Growth Imperative. Ambleside, UK: University of Cumbria, Available online: https://insight.cumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/5993 (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- Banerjee, Abhijit V., and Eric S. Maskin. 1996. A Walrasian Theory of Money and Barter. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 111: 955–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Batrancea, Ioan, Larissa Batrancea, Malar Maran Rathnaswamy, Horia Tulai, Gheorghe Fatacean, and Mircea-Iosif Rus. 2020. Greening the Financial System in USA, Canada and Brazil: A Panel Data Analysis. Mathematics 8: 2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, Alex, and Cameron Hepburn. 2014. Green growth: An assessment. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 30: 407–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesbank, Deutsche. 2017. The role of banks, nonbanks and the central bank in the money creation process. Monthly Report 69: 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cahen-Fourot, Louison, and Marc Lavoie. 2016. Ecological monetary economics: A post-Keynesian critique. Ecological Economics 126: 163–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caiani, Alessandro, Antoine Godin, Eugenio Caverzasi, Mauro Gallegati, Stephen Kinsella, and Joseph E. Stiglitz. 2016. Agent based-stock flow consistent macroeconomics: Towards a benchmark model. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 69: 375–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- D’Alessandro, Simone, André Cieplinski, Tiziano Distefano, and Kristofer Dittmer. 2020. Feasible alternatives to green growth. Nature Sustainability 3: 329–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogaru, Lucreția. 2021. Green Economy and Green Growth—Opportunities for Sustainable Development. Paper presented at the 14th International Conference on Interdisciplinarity in Engineering—INTER-ENG 2020, Târgu Mureș, Romania, October 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Farley, Joshua, Matthew Burke, Gary Flomenhoft, Brian Kelly, D. Forrest Murray, Stephen Posner, Matthew Putnam, Adam Scanlan, and Aaron Witham. 2013. Monetary and Fiscal Policies for a Finite Planet. Sustainability 5: 2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Godley, Wynne, and Marc Lavoie. 2012. Monetary Economics. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godley, Wynne. 2004. Towards a Reconstruction of Macroeconomics Using a Stock Flow Consistent (SFC) Model. University of Cambridge: Available online: https://www.repository.cam.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1810/225167/wp16.pdf;jsessionid=90B9B20A5C98CDBF38CA6F162D785CAE?sequence=1 (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- Gross, Mr Marco, and Christoph Siebenbrunner. 2019. Money Creation in Fiat and Digital Currency Systems. IMF Working Papers Volume 2019, Issue 285. Available online: https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/journals/001/2019/285/001.2019.issue-285-en.xml (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- Hallegatte, Stéphane, Geoffrey Heal, Marianne Fay, and David Treguer. 2012. From Growth to Green Growth—A Framework (No. w17841). Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepburn, Cameron, Alexander Pfeiffer, and Alexander Teytelboym. 2018. Green Growth—Oxford Handbooks. In The New Oxford Handbook of Economic Geography. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickel, Jason, and Giorgos Kallis. 2019. Is Green Growth Possible? New Political Economy 25: 469–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. 2018. Special Report—Global Warming of 1.5 °C. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/ (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- IPCC. 2019a. Special Report—Climate Change and Land. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/srccl/ (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- IPCC. 2019b. Special Report—The Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/srocc/ (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- Jackson, Tim, and Peter A. Victor. 2015. Does credit create a ‘growth imperative’? A quasi-stationary economy with interest-bearing debt. Ecological Economics 120: 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelton, Stephanie. 2020. The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and How to Build a Better Economy. London: John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Kingsley, Kelly Mua. 2017. Green Financing. SSRN Electronic Journal. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2940765 (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- Kinsella, Stephen, and Terence O’Shea. 2011. Solution and Simulation of Large Stock Flow Consistent Monetary Production Models Via the Gauss Seidel Algorithm. SSRN Journal. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1729205 (accessed on 13 July 2021). [CrossRef]

- Koo, Richard C. 2013. Balance sheet recession as the ‘other half’ of macroeconomics. European Journal of Economics and Economic Policies 10: 136–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laeven, Mr Luc, and Mr Fabian Valencia. 2018. Systemic Banking Crises Revisited. IMF Working Papers 18. Washington: IMF. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larissa, Batrancea, Rathnaswamy Malar Maran, Batrancea Ioan, Nichita Anca, Rus Mircea-Iosif, Tulai Horia, Fatacean Gheorghe, Masca Ema Speranta, and Morar Ioan Dan. 2020. Adjusted Net Savings of CEE and Baltic Nations in the Context of Sustainable Economic Growth: A Panel Data Analysis. Journal of Risk and Financial Management 13: 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavoie, Marc, and Wynne Godley. 2002. Kaleckian Models of Growth in a Coherent Stock-Flow Monetary Framework: A Kaldorian View. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 24: 277–311. Available online: http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/Lavoie%20Godley_2001-02.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2021). [CrossRef]

- Li, Zhi, Po-Hsuan Lin, Si-Yuan Kong, Dongwu Wang, and John Duffy. 2021. Conducting large, repeated, multi-game economic experiments using mobile platforms. PLoS ONE 16: e0250668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lietaer, Bernard, Christian Arnsperger, Sally Goerner, and Stefan Brunnhuber. 2012. Money—Sustainability: The Missing Link. Devon: Triarchy Press, Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271506661_Money_and_sustainability_the_missing_link_a_report_from_the_Club_of_Rome_-_EU_Chapter_to_Finance_Watch_and_the_World_Business_Academy (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- McLeay, Michael, Amar Radia, and Ryland Thomas. 2014. Money Creation in the Modern Economy. London: Bank of England, Available online: https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/quarterly-bulletin/2014/money-creation-in-the-modern-economy.pdf?la=en&hash=9A8788FD44A62D8BB927123544205CE476E01654 (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- Nayan, Sabri, Norsiah Kadir, Mat Saad Abdullah, and Mahyudin Ahmad. 2013. Post Keynesian Endogeneity of Money Supply: Panel Evidence. Procedia Economics and Finance 7: 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nikiforos, Michalis, and Gennaro Zezza. 2017. Stock-Flow Consistent Macroeconomic Models: A Survey. Annandale-On-Hudson: Levy Economics Institute, Available online: https://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp_891.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- Nordhaus, William. 2015. Climate Clubs: Overcoming Free-riding in International Climate Policy. American Economic Review 105: 1339–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- OECD. 2011. Towards Green Growth. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/greengrowth/48012345.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- OECD. 2012. OECD Environmental Outlook to 2050: The Consequences of Inaction, Paris, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/g20/topics/energy-environment-green-growth/oecdenvironmentaloutlookto2050theconsequencesofinaction.htm (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- OECD. 2020. Beyond Growth: Towards a New Economic Approach, New Approaches to Economic Challenges. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozili, Peterson K. 2021. Digital Finance, Green Finance and Social Finance: Is There a Link? Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3786881 (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- Parrique, Timothée, Barth Jonathan, Briens François, Kerschner Christian, Kraus-Polk Alejo, Kuokkanen Anna, and Spangenberg Joachim H. 2019. Decoupling Debunked: Evidence and Arguments Against Green Growth as a Sole Strategy for Sustainability. Brussels: European Environmental Bureau, Available online: https://eeb.org/library/decoupling-debunked/ (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- Ramsey, David M., and Jérôme Renault, eds. 2020. Advances in Dynamic Games: Games of Conflict, Evolutionary Games, Economic Games, and Games Involving Common Interest, Annals of the International Society of Dynamic Games. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richters, Oliver, and Andreas Siemoneit. 2017. Consistency and stability analysis of models of a monetary growth imperative. Ecological Economics 136: 114–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stone, Mark R., Kenji Fujita, and Ishi Kotaro. 2011. Should Unconventional Balance Sheet Policies Be Added to the Central Bank toolkit? a Review of the Experience so Far; IMF Working Papers 11. Washington: IMF. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2011/wp11145.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2021).

- Werner, Richard A. 2014. Can banks individually create money out of nothing?—The theories and the empirical evidence. International Review of Financial Analysis 36: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Werner, Richard A. 2016. A lost century in economics: Three theories of banking and the conclusive evidence. International Review of Financial Analysis 46: 361–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuypers, S.; Goorden, T.; Delepierre, B. Computational Analysis of the Properties of Post-Keynesian Endogenous Money Systems. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2021, 14, 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14070335

Kuypers S, Goorden T, Delepierre B. Computational Analysis of the Properties of Post-Keynesian Endogenous Money Systems. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2021; 14(7):335. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14070335

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuypers, Stef, Thomas Goorden, and Bruno Delepierre. 2021. "Computational Analysis of the Properties of Post-Keynesian Endogenous Money Systems" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14, no. 7: 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14070335

APA StyleKuypers, S., Goorden, T., & Delepierre, B. (2021). Computational Analysis of the Properties of Post-Keynesian Endogenous Money Systems. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(7), 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14070335