Analysis of MnS Inclusions Formation in Resulphurised Steel via Modeling and Experiments

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental

3. Coupled Model of Solute Segregation and Inclusion Growth

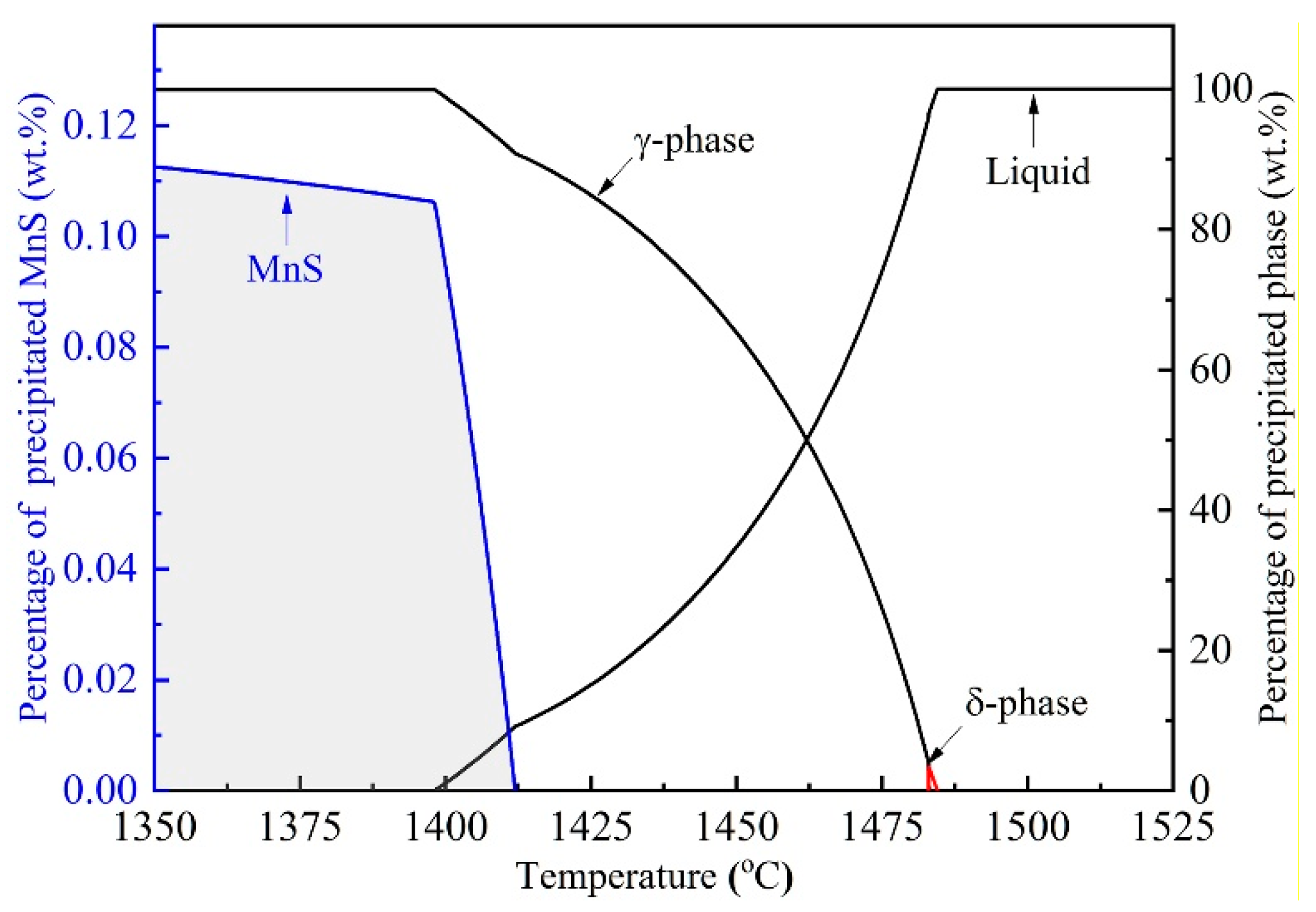

3.1. Thermodynamics of MnS Precipitation Process

3.2. Nucleation

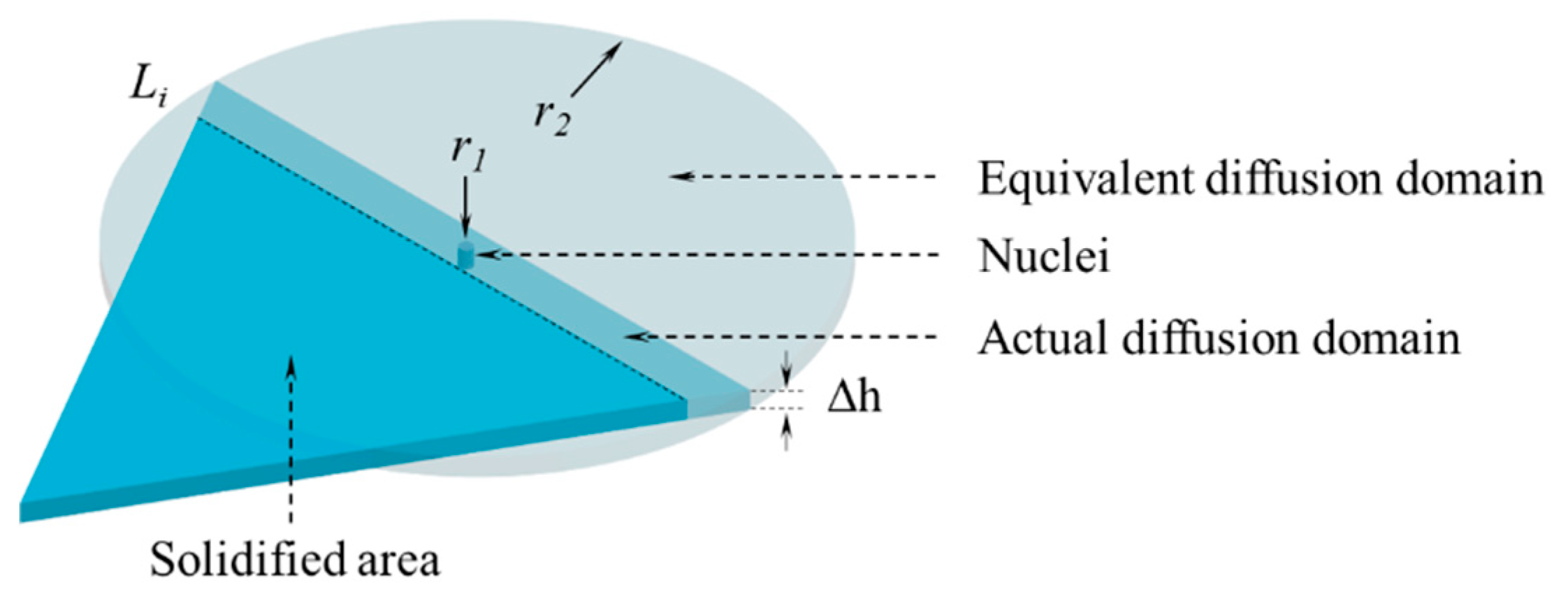

3.3. Growth of Nuclei

3.4. Calculation Solution of the Model

4. Analysis and Discussion

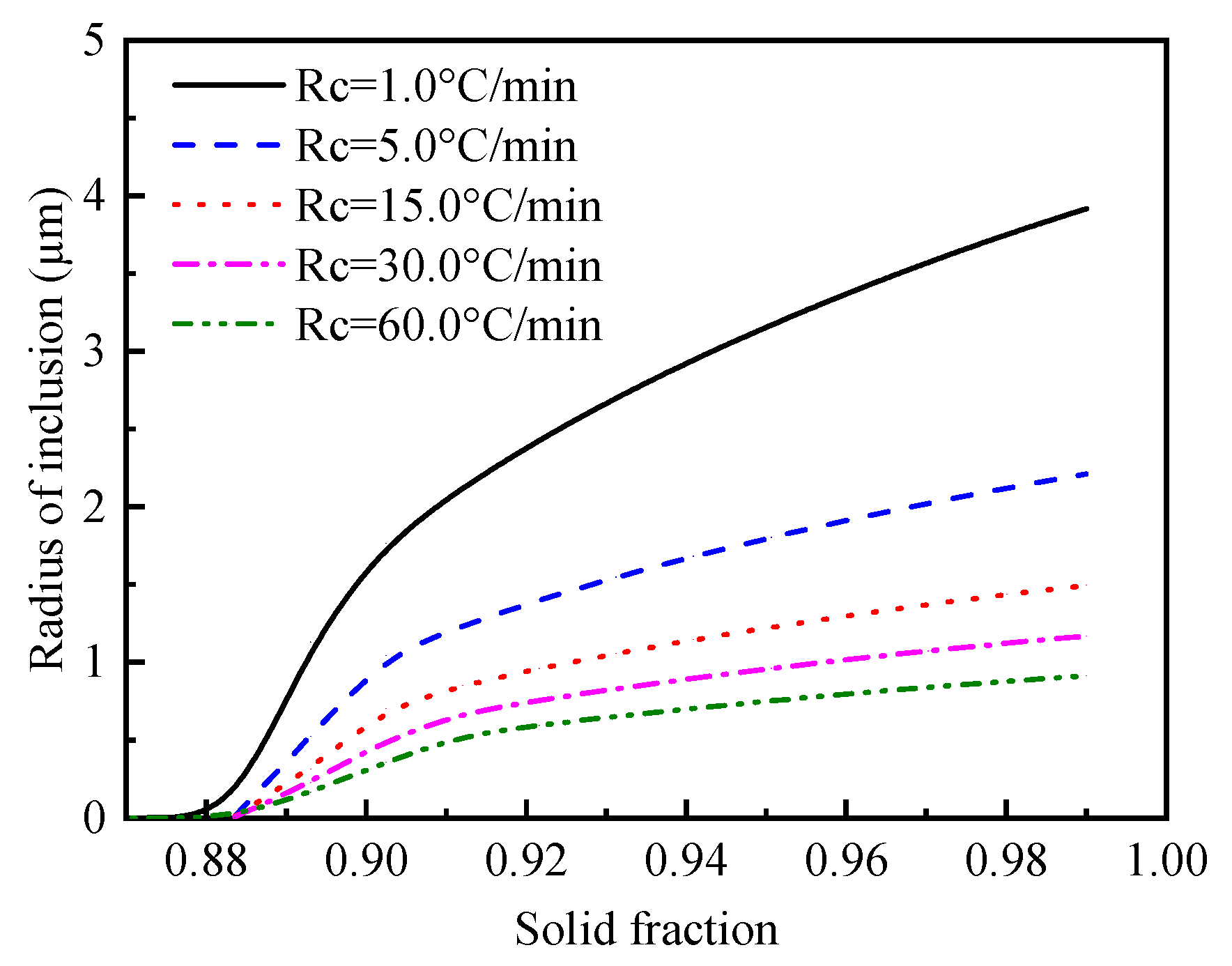

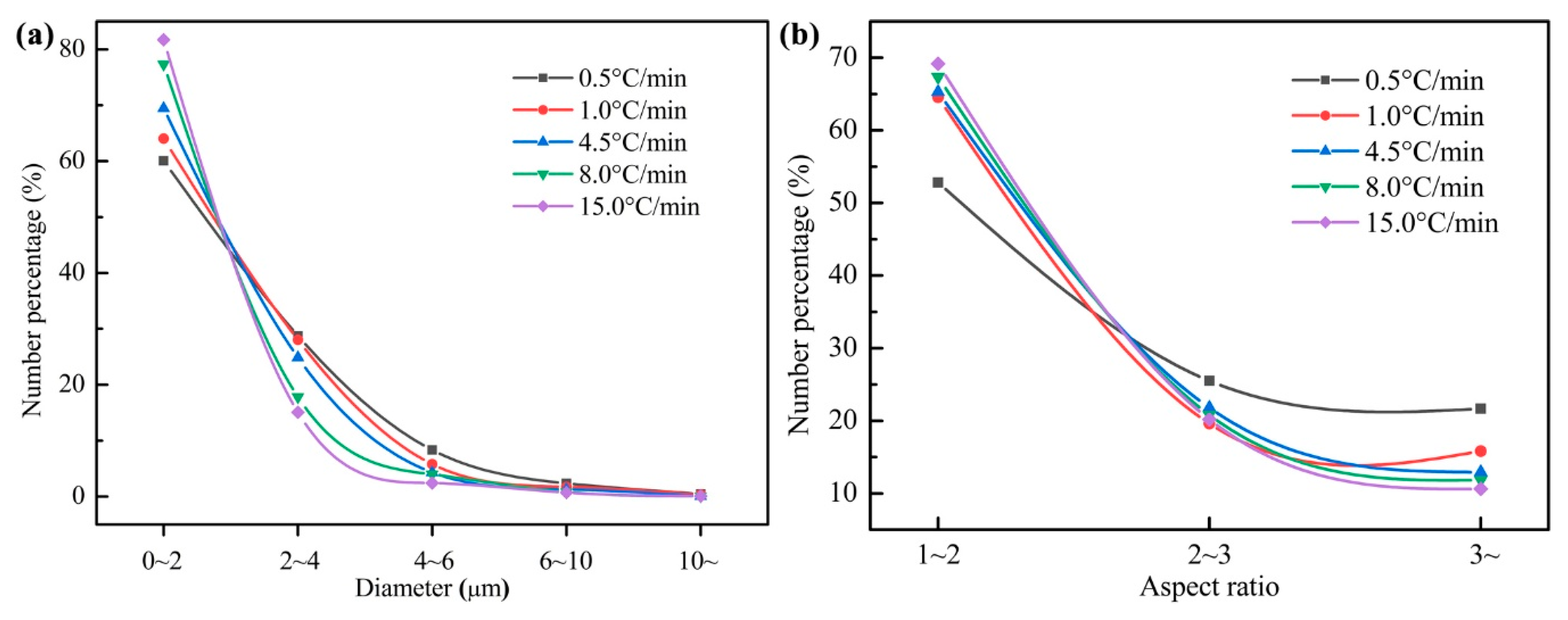

4.1. Effect of Cooling Rate on MnS Formation

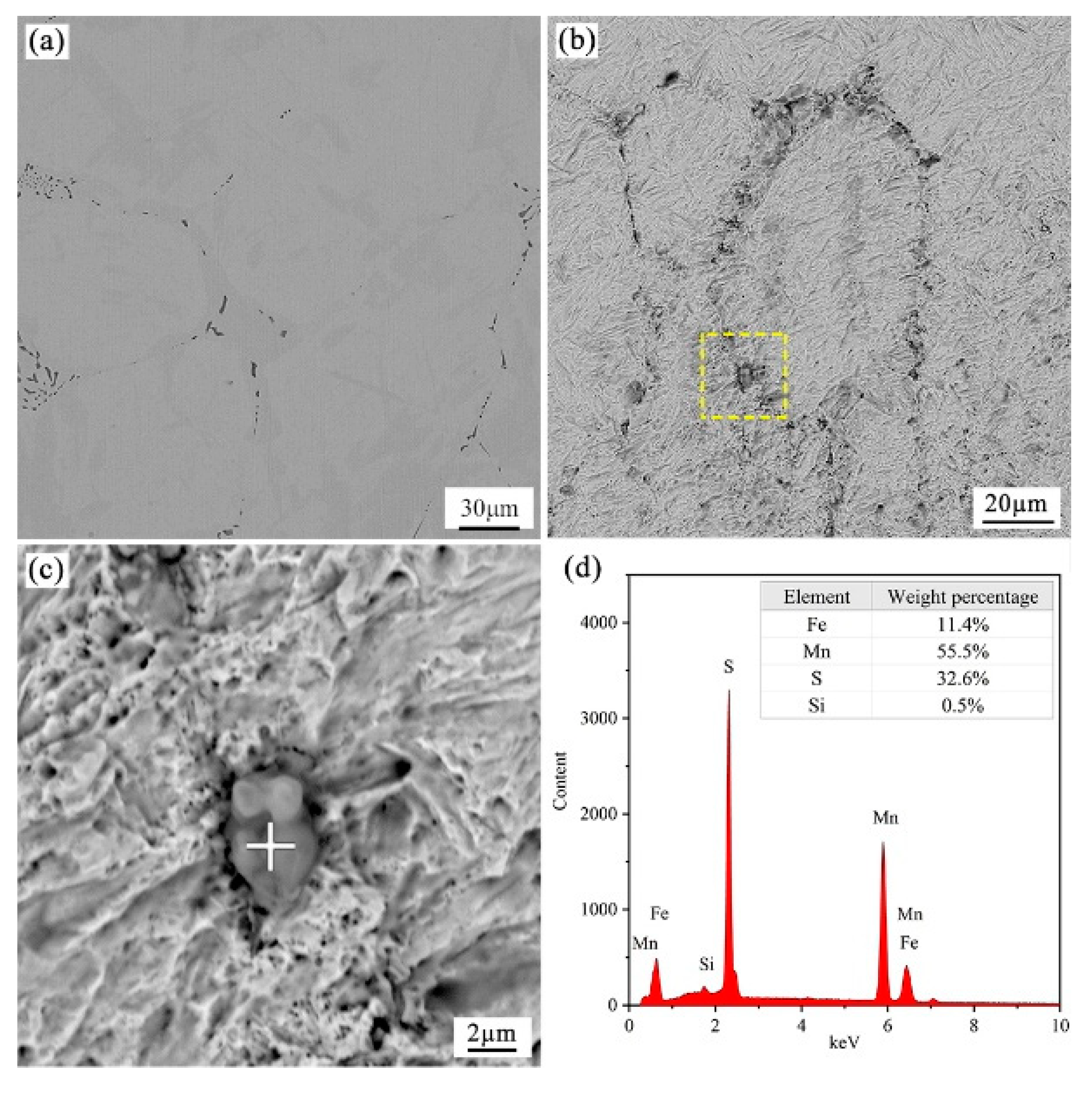

4.2. Observation of Samples and Analysis of Inclusions

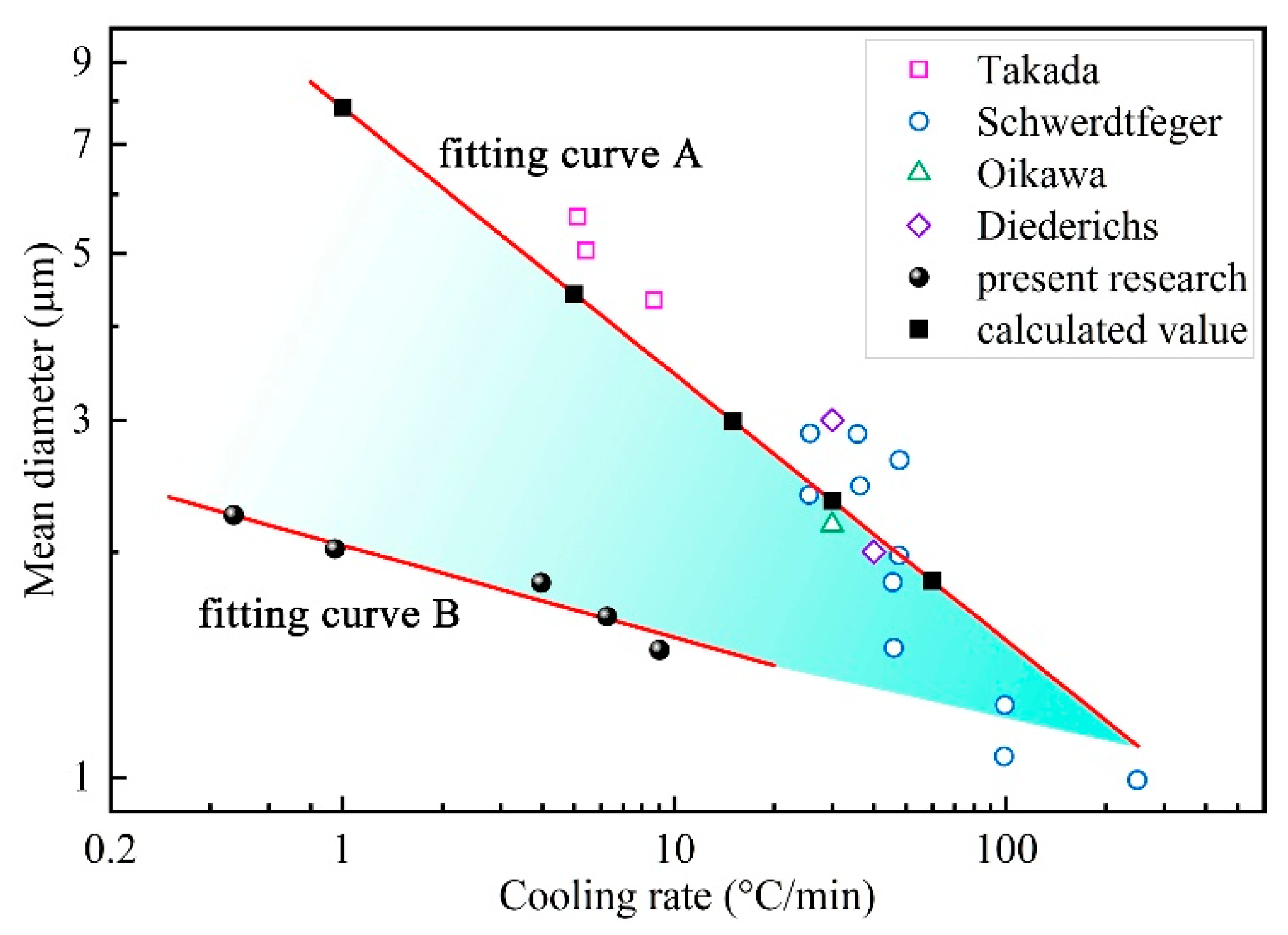

4.3. Comparison Between Experiment and Calculation

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The MnS begins to precipitate in the remnant liquid when local solubility product of manganese and sulfur exceeds the equilibrium value, and the segregation ratio of solute Mn and S are approximately 1.57 and 6.87 at the beginning of MnS formation.

- (2)

- The solute element of S was the determining species in deciding the nucleation and precipitation of MnS, while the solute element Mn affected the precipitated amount of MnS owing to the high partition coefficient in solid phase.

- (3)

- The current coupled model can be used to simulate the growth of MnS inclusions in resulfurized steel, and the calculated size of the formed MnS inclusions fits well with the previous experimental results. The value of the MnS size is evidently affected by cooling rate, and the relationships between dMnS-H and dMnS-L with υ were given by the mathematical expressions as follows: ; .

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Byun, J.S.; Shim, J.H.; Cho, Y.W.; Lee, D.N. Non-metallic inclusion and intragranular nucleation of ferrite in Ti-killed C-Mn steel. Acta Mater. 2003, 51, 1593–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madariaga, I.; Gutiérrez, I. Role of the particle-matrix interface on the nucleation of acicular ferrite in a medium carbon microalloyed steel. Acta Mater. 1999, 47, 951–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Eijk, C.; Grong, Ø.; Haakonsen, F.; Kolbeinsen, L.; Tranell, G. Progress in the development and use of grain refiner based on cerium sulfide or titanium compound for carbon steel. ISIJ Int. 2009, 49, 1046–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Dong, H.; Wang, M.; Hui, W. Effect of Sulfur Content and Sulfide Shape on Fracture Ductility in Case Hardening Steel. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2011, 18, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Fu, J. Morphology Study on Inclusion Modifications Using Mg-Ca Treatment in Resulfurized Special Steel. Materials 2019, 12, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, C.; Mu, H.; Li, Y.; Jiang, M. Inclusion evolution after calcium addition in Al-killed steel with different sulphur content. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2018, 45, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, S.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Ju, J. Effect of Mg addition on the refinement and homogenized distribution of inclusions in steel with different Al contents. Met. Mater. Trans. B 2017, 48, 805–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Bao, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhao, L. Effect of Mg and Ca treatment on behavior and particle size of inclusions in bearing steels. ISIJ Int. 2014, 54, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakama, K.; Haruna, Y.; Nakano, J.; Sridhar, S. The Effect of Alloy Solidification Path on Sulfide Formation in Fe-Cr-Ni Alloys. ISIJ Int. 2009, 49, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clyne, T.W.; Kurz, W. Solute redistribution during solidification with rapid solid state diffusion. Met. Mater. Trans. A 1981, 2, 65–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, H.D.; Flemings, M.C. Solute redistribution in dendritic solidification. Tran. Metall. AIME 1966, 615–624. [Google Scholar]

- Ohnaka, I. Mathematical analysis of solute redistribution during solidification with diffusion in solid phase. ISIJ Int. 1986, 26, 1045–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S. A Mathematical Model for Solute Redistribution during Dendritic Solidification. ISIJ Int. 1988, 28, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.; Viskanta, R. Solute redistribution limit in coarsening dendrite arms during binary alloy solidification. Int. J. Heat Mass. Tran. 1997, 40, 3875–3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voller, V.R. A semi-analytical model of microsegregation in a binary alloy. J. Cryst. Growth 1999, 197, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, Y.; Thomas, B.G. Simple model of microsegregation during solidification of steels. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2001, 32, 1755–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, D.; Michelic, S.K.; Wieser, G.; Bernhard, C. Modeling of manganese sulfide formation during the solidification of steel. J. Mater. Sci. 2017, 52, 1797–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Gao, X.; Huang, S.; Zhu, M. Cross-Scale Modeling of MnS Precipitation for Steel Solidification. Metals 2018, 8, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Hu, D.; Wu, Y.; Huang, Z.; An, J.; Fu, J. Study of manganese sulfide precipitation in medium sulfur, non-quenched and tempered steel via experiments and thermodynamic calculation. Met. Res. Technol. 2018, 115, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Liu, H.; Xie, J.; Cheng, J.; Li, J.; Fu, J. Analysis of precipitation behavior of MnS in sulfur-bearing steel system with finite-difference segregation model. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2018, 25, 803–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janis, D.; Inoue, R.; Karasev, A.; Jönsson, P. Application of Different Extraction Methods for Investigation of Nonmetallic Inclusions and Clusters in Steels and Alloys. Adv. Mater. Sci Eng. 2014, 2014, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, D.; Shen, P.; Xie, J.; An, J.; Huang, Z.; Fu, J. A method for observing tridimensional morphology of sulfide inclusions by non-aqueous solution electrolytic etching. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2019, 26, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueshima, Y.; Mizoguchi, S.; Matsumiya, T.; Kajioka, H. Analysis of solute distribution in dendrites of carbon steel with δ/γ transformation during solidification. Met. Mater. Trans. B 1986, 7, 45–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wei, J.; Cai, K. A Coupled Mathematical Model of Microsegregation and Inclusion Precipitation during Solidification of Silicon Steel. ISIJ Int. 2002, 42, 958–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.P.; Militzer, M.; Jonas, J.J. Strain-induced nucleation of MnS in electrical steels. Met. Mater. Trans. A 1992, 23, 821–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Kang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, H. Morphology and Precipitation Kinetics of MnS in Low-Carbon Steel During Thin Slab Continuous Casting Process. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2006, 13, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.J.; Jonas, J.J. Nucleation kinetics of Ti carbonitride in microalloyed austenite. Met. Mater. Trans. A 1989, 20, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, A. Precipitation of AlN and MnS in Low Carbon Aluminium-Killed Steel. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2012, 19, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, B.; Palmiere, E.J.; Sellars, C.M. Modelling the kinetics of strain induced precipitation in Nb microalloyed steels. Acta Mater. 2001, 49, 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Yang, W.; Shi, X.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, S.; Duan, S.; Wu, J.; Guo, H. Effect of Sulfur Content on the Properties and MnS Morphologies of DH36 Structural Steel. Metals 2018, 8, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Oh Kyu, H.; Lee, D.N. Mechanical behavior of carbon steels during continuous casting. Scr. Mater. 1996, 34, 301–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueshima, Y.; Sawada, Y.; Mizoguchi, S.; Kajioka, H. Precipitation behavior of MnS during δ/γ transformation in Fe-Si alloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 1989, 20, 1375–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhu, M.; Cai, Z.; Luo, S.; Ji, C. Micro-Segregation Behavior of Solute Elements in the Mushy Zone of Continuous Casting Wide-Thick Slab. Steel Res. Int. 2012, 83, 1152–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bale, C.W.; Chartrand, P.; Degterov, S.A.; Eriksson, G.; Hack, K.; Ben Mahfoud, R.; Melançon, J.; Pelton, A.D.; Petersen, S. FactSage thermochemical software and databases. Calphad 2002, 26, 189–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bale, C.W.; Bélisle, E.; Chartrand, P.; Decterov, S.A.; Eriksson, G.; Hack, K.; Jung, I.; Kang, Y.; Melançon, J.; Pelton, A.D. FactSage thermochemical software and databases—Recent developments. Calphad 2009, 33, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bale, C.W.; Bélisle, E.; Chartrand, P.; Decterov, S.A.; Eriksson, G.; Gheribi, A.E.; Hack, K.; Jung, I.; Kang, Y.; Melançon, J. Reprint of: FactSage thermochemical software and databases, 2010–2016. Calphad 2016, 55, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwerdtfeger, K. Einfluß der Erstarrungsgeschwindigkeit auf die Mikroseigerung und die interdendritische Ausscheidung von Mangansulfideinschlüssen in einem Mangan und Kohlenstoff enthaltenden Stahl. Archiv Für Das Eisenhüttenwesen 1970, 41, 923–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takada, H.; Bessho, I.; Ito, T. Effect of Sulfur Content and Solidification Variables on Morphology and Distribution of Sulfide in Steel Ingots. ISIJ Int. 1976, 62, 1319–1328. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Oikawa, K.; Ishida, K.; Nishizawa, T. Effect of Titanium Addition on the Formation and Distribution of MnS Inclusions in Steel during Solidification. ISIJ Int. 1997, 37, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diederichs, R.; Bleck, W. Modelling of manganese sulphide formation during solidification, part I: Description of MnS formation parameters. Steel Res. Int. 2006, 77, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| C | Si | Mn | P | S | Al | O | N | Cr | Fe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.48 | 0.35 | 0.91 | 0.013 | 0.047 | 0.012 | 0.0015 | 0.007 | 0.2 | Balance |

| C | Si | Mn | P | S | Cr | Ni | Mo | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn | −0.07 | 0 | 0 | −0.0035 | −0.048 | - | - | - |

| S | 0.11 | 0.063 | −0.026 | 0.029 | −0.028 | −0.011 | 0 | 0.0027 |

| Parameter | γ-Phase | α-Phase |

|---|---|---|

| Lattice parameter of MnS at room temperature (nm) | 0.5223 | 0.2866 |

| Linear expansion efficient of MnS (K−1) | 1.81 × 10−5 | 1.81 × 10−5 |

| Specific interface energy σ (J/m2) | 1.7969 − 0.8097 × 10−3 T | 0.8157 − 0.2921 × 10−3 T |

| Diffusion activation energy of Mn atom(J) | 0.4334 × 10−18 | 0.3653 × 10−18 |

| Lattice constant of matrix (nm) | 0.3591 | 0.2863 |

| Element | mi (°C pct−1) | ni (°C pct−1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 0.19 | 0.34 | 0.56 | 78 | −1122 | ||

| Si | 0.77 | 0.52 | 1.47 | 7.6 | 60 | ||

| Mn | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.97 | 4.9 | −12 | ||

| P | 0.23 | 0.13 | 1.75 | 34.4 | 140 | ||

| S | 0.05 | 0.035 | 1.43 | 38 | 160 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, H.; Hu, D.; Fu, J. Analysis of MnS Inclusions Formation in Resulphurised Steel via Modeling and Experiments. Materials 2019, 12, 2028. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12122028

Liu H, Hu D, Fu J. Analysis of MnS Inclusions Formation in Resulphurised Steel via Modeling and Experiments. Materials. 2019; 12(12):2028. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12122028

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Hui, Delin Hu, and Jianxun Fu. 2019. "Analysis of MnS Inclusions Formation in Resulphurised Steel via Modeling and Experiments" Materials 12, no. 12: 2028. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma12122028