Sustainable Binary Blending for Low-Volume Roads—Reliability-Based Design Approach and Carbon Footprint Analysis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Soil

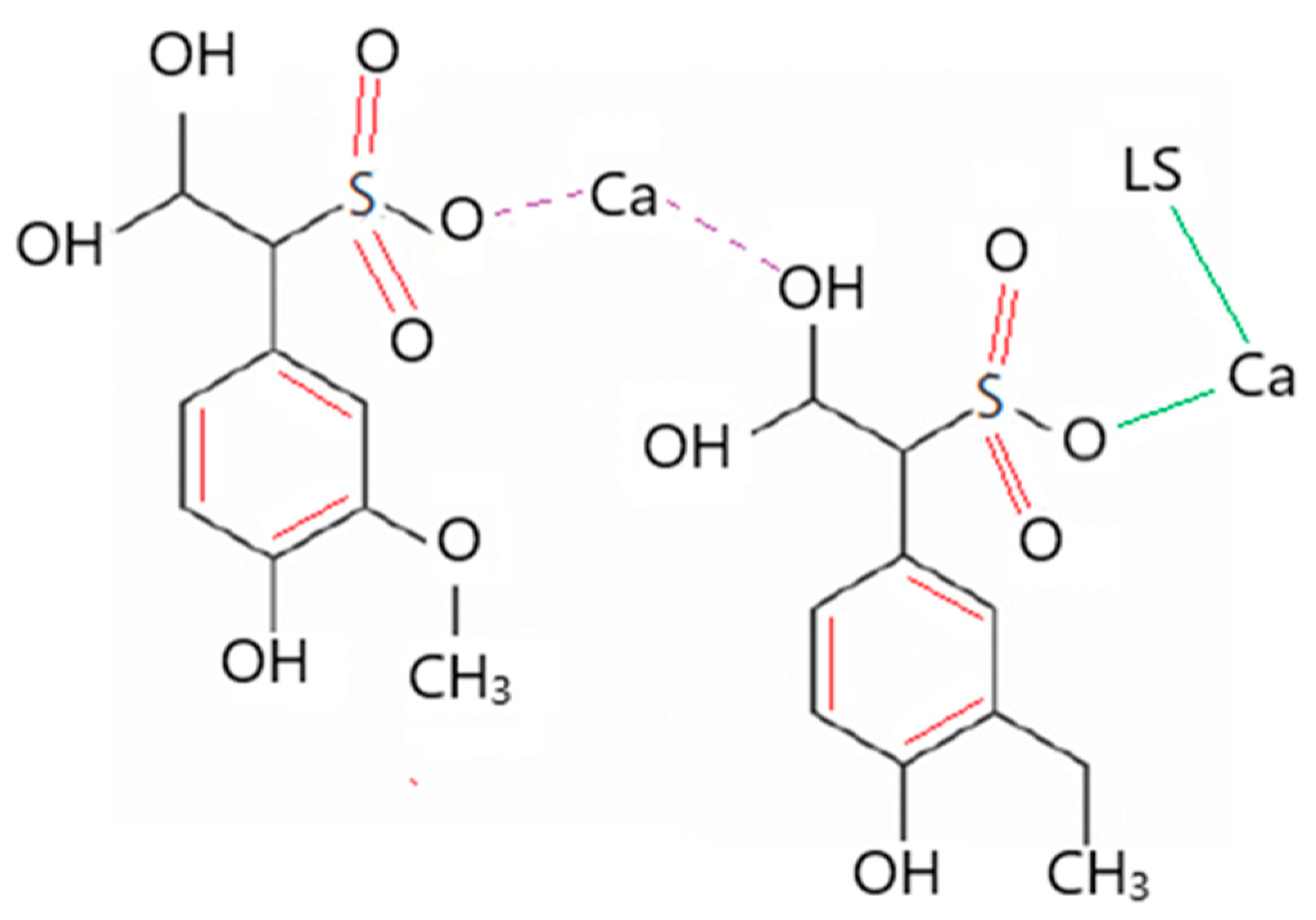

2.2. Primary Additive

2.3. Secondary Additive

- M1: 70% clay and 30% GS

- M2: 60% clay and 40% GS

- M3: 50% clay and 50% GS

- M1CLS0.5: 70% clay and 30% GS and 0.5% CLS

- M1CLS1: 70% clay and 30% GS and 1% CLS

- M1CLS1.5: 70% clay and 30% GS and 1.5% CLS

- M1CLS2: 70% clay and 30% GS and 2% CLS

- M2CLS0.5: 60% clay and 40% GS and 0.5% CLS

- M2CLS1: 60% clay and 40% GS and 1% CLS

- M2CLS1.5: 60% clay and 40% GS and 1.5% CLS

- M2CLS2: 60% clay and 40% GS and 2% CLS

- M3CLS0.5: 50% clay and 50% GS and 0.5% CLS

- M3CLS1: 50% clay and 50% GS and 1% CLS

- M3CLS1.5: 50% clay and 50% GS and 1.5% CLS

- M3CLS2: 50% clay and 50% GS and 2% CLS

2.4. California Bearing Ratio (CBR)

2.4.1. Sample Preparation with GS

2.4.2. Sample Preparation with GS and CLS

2.5. Microstructural Analysis

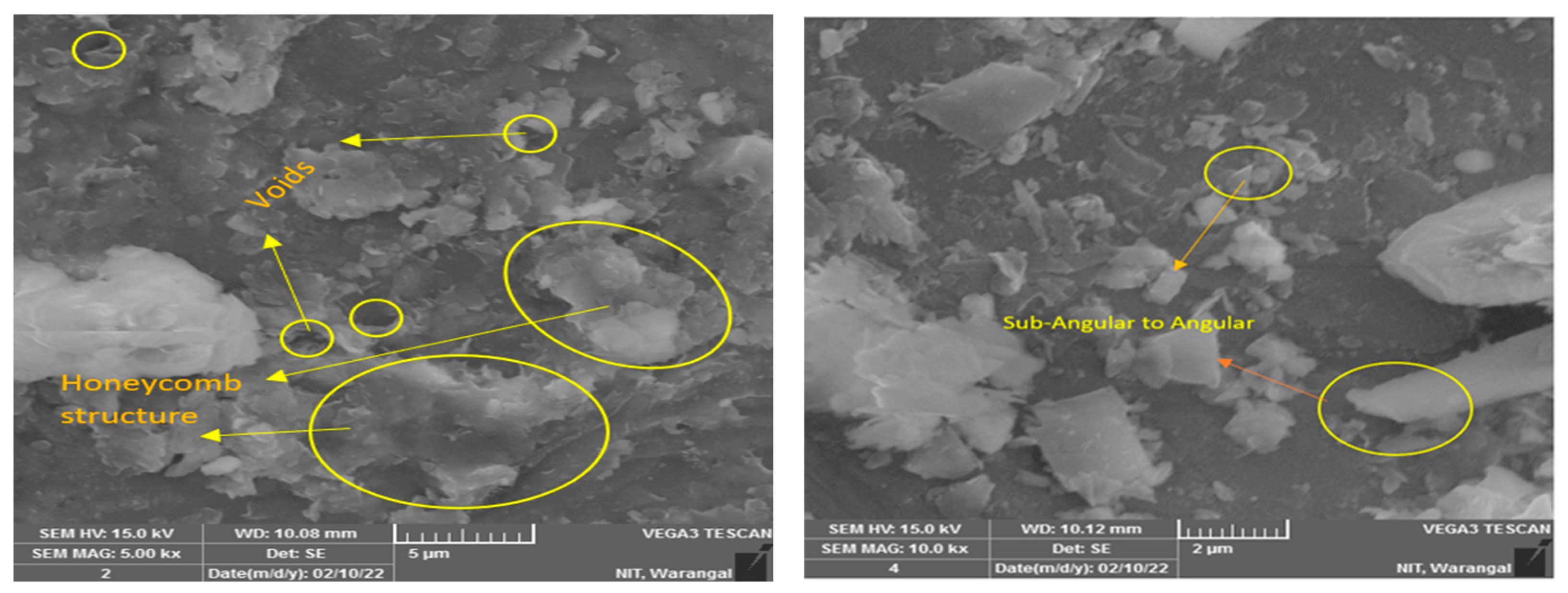

2.5.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy Analysis (SEM)

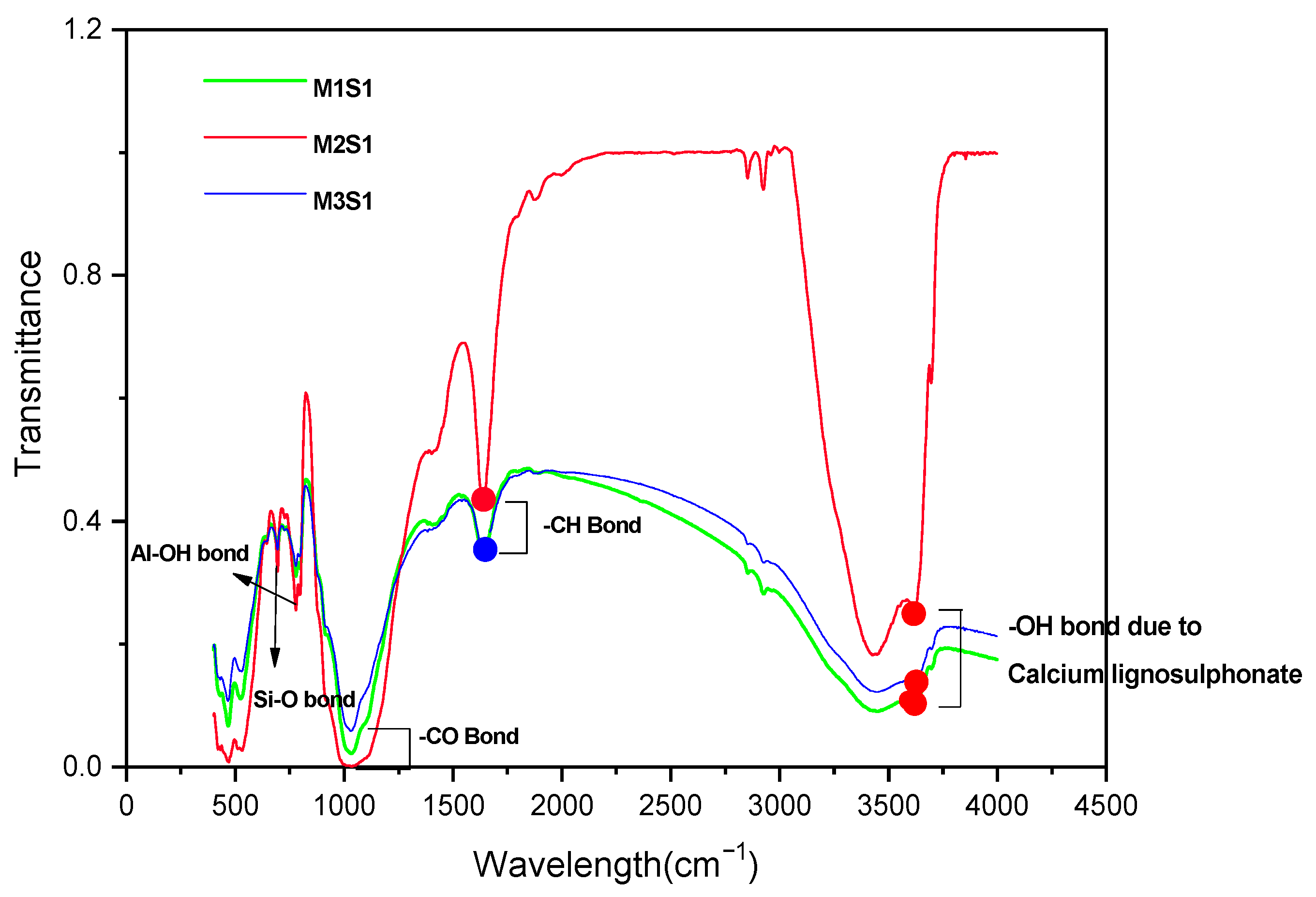

2.5.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

2.6. Low-Volume Roads (LVRs)

2.7. Reliability Analysis

2.7.1. Need for Reliability-Based Design

2.7.2. Previous Studies on Reliability Analysis of Pavements

2.7.3. Reliability Analysis Procedure

2.7.4. Regression Analysis of the CBR Data Obtained from Experiments

2.7.5. Performance Function for RBDO

2.7.6. Estimation of Reliability Indices Using FORM

2.8. Carbon Footprint Analysis (CFA)

- Stage I: Estimate the amount of carbon evolved from materials used for the pavement subgrade application.

- Stage II: Estimate the amount of carbon evolved during the procurement and haulage of the materials.

- Stage III: Estimate the carbon emissions during site operations.

Boundary Conditions

- Equivalent carbon emissions are calculated based on the dosage of clay, GS and CLS.

- A uniform density of 1.75 g/cc is maintained to compact the soil for the entire section.

- A measurable moisture content of 16.3% is considered for effective compaction throughout the project.

- The manufacturing process is excluded from the calculations, as the materials are applicable for various purposes.

- The embodied carbon factor for maintenance and disposal processes is not considered because the selected material satisfied the technical requirement.

3. Results and Discussion

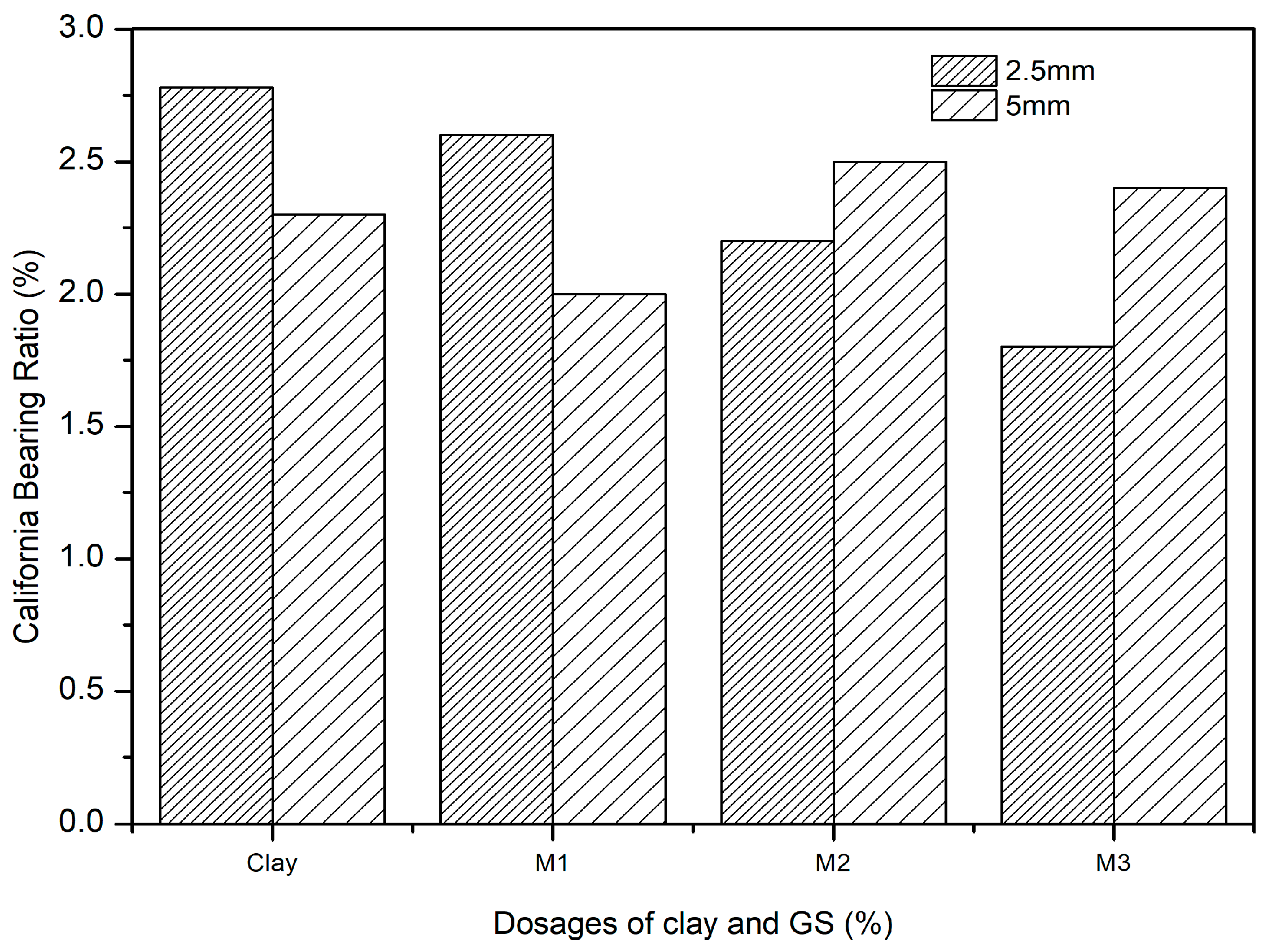

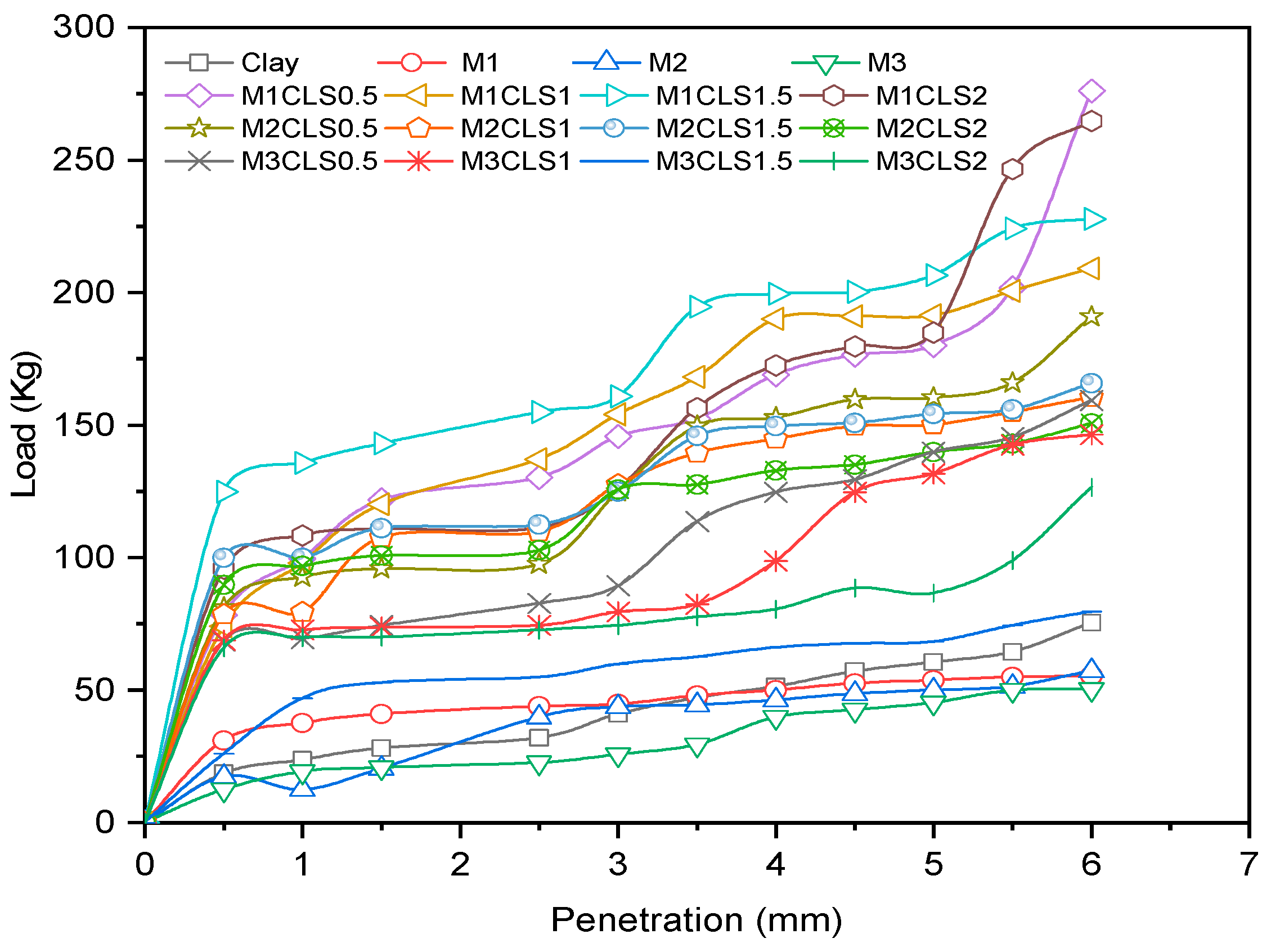

3.1. Variation in CBR with GS

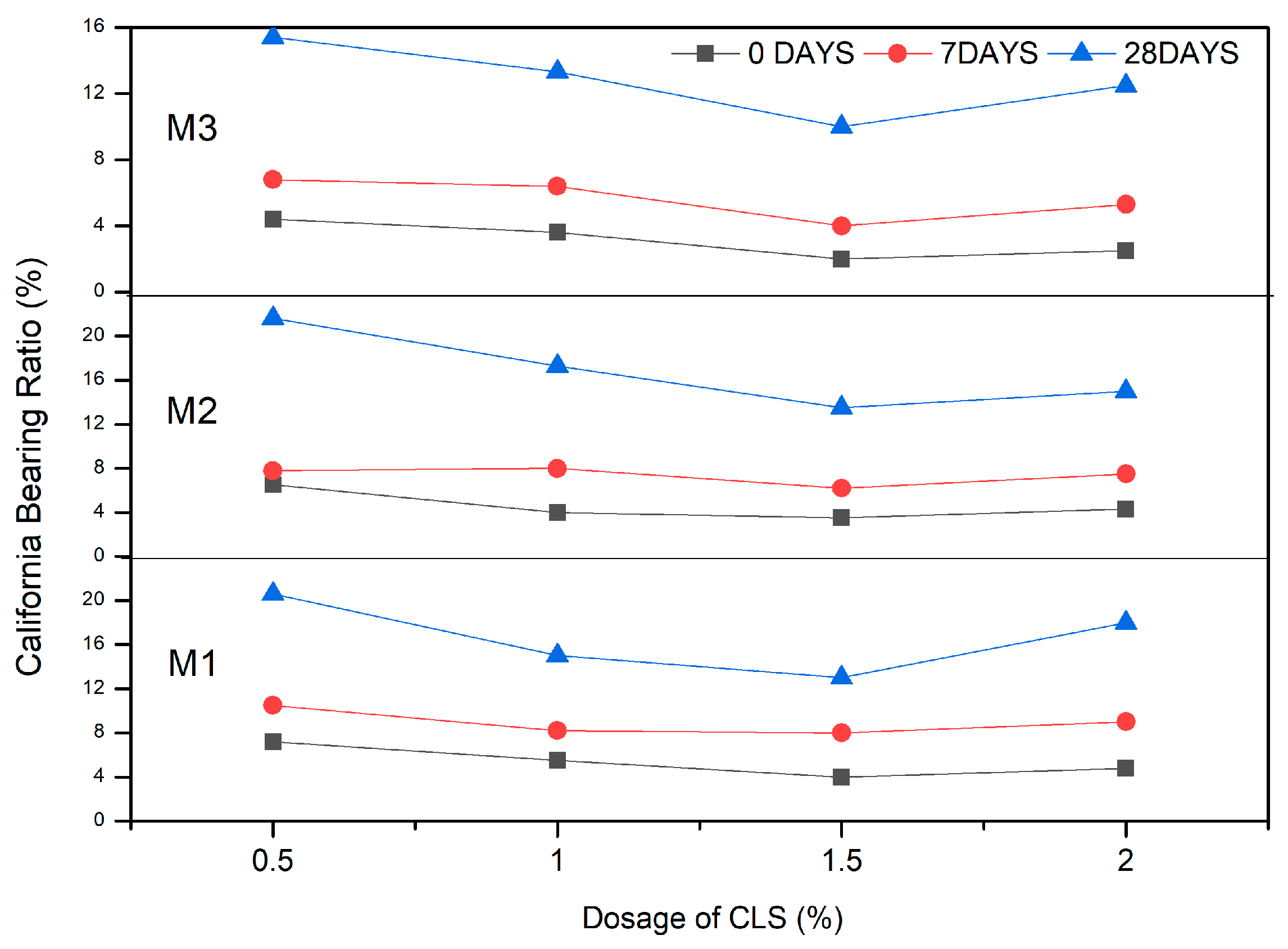

3.2. Variation in CBR with GS and CLS

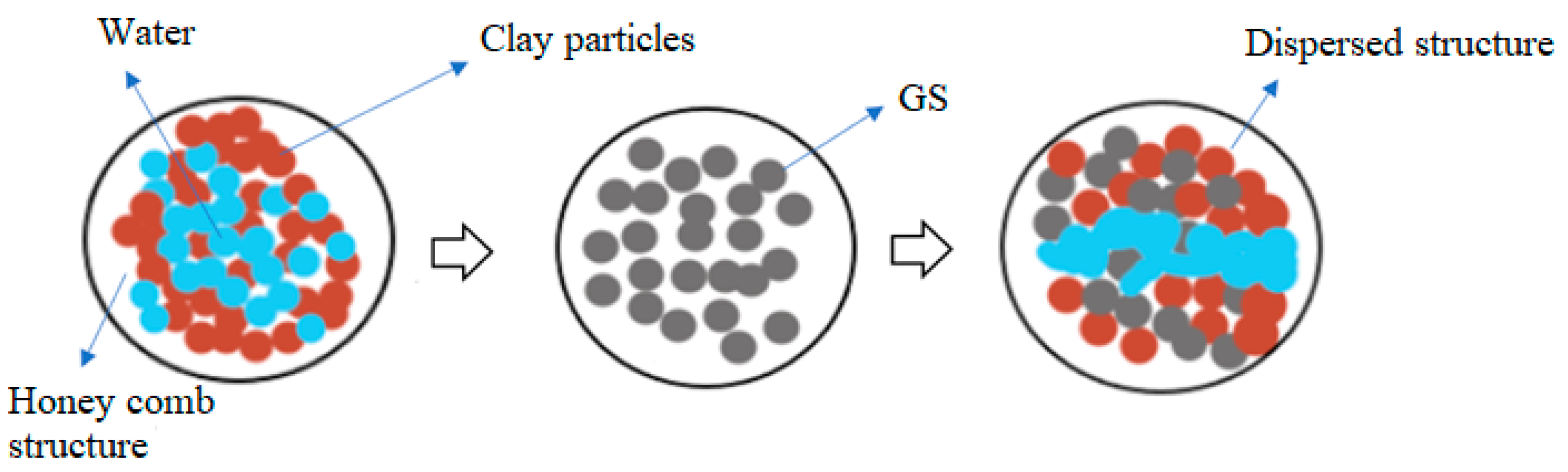

3.2.1. Effect of GS

3.2.2. Effect of CLS

3.2.3. Effect of Curing

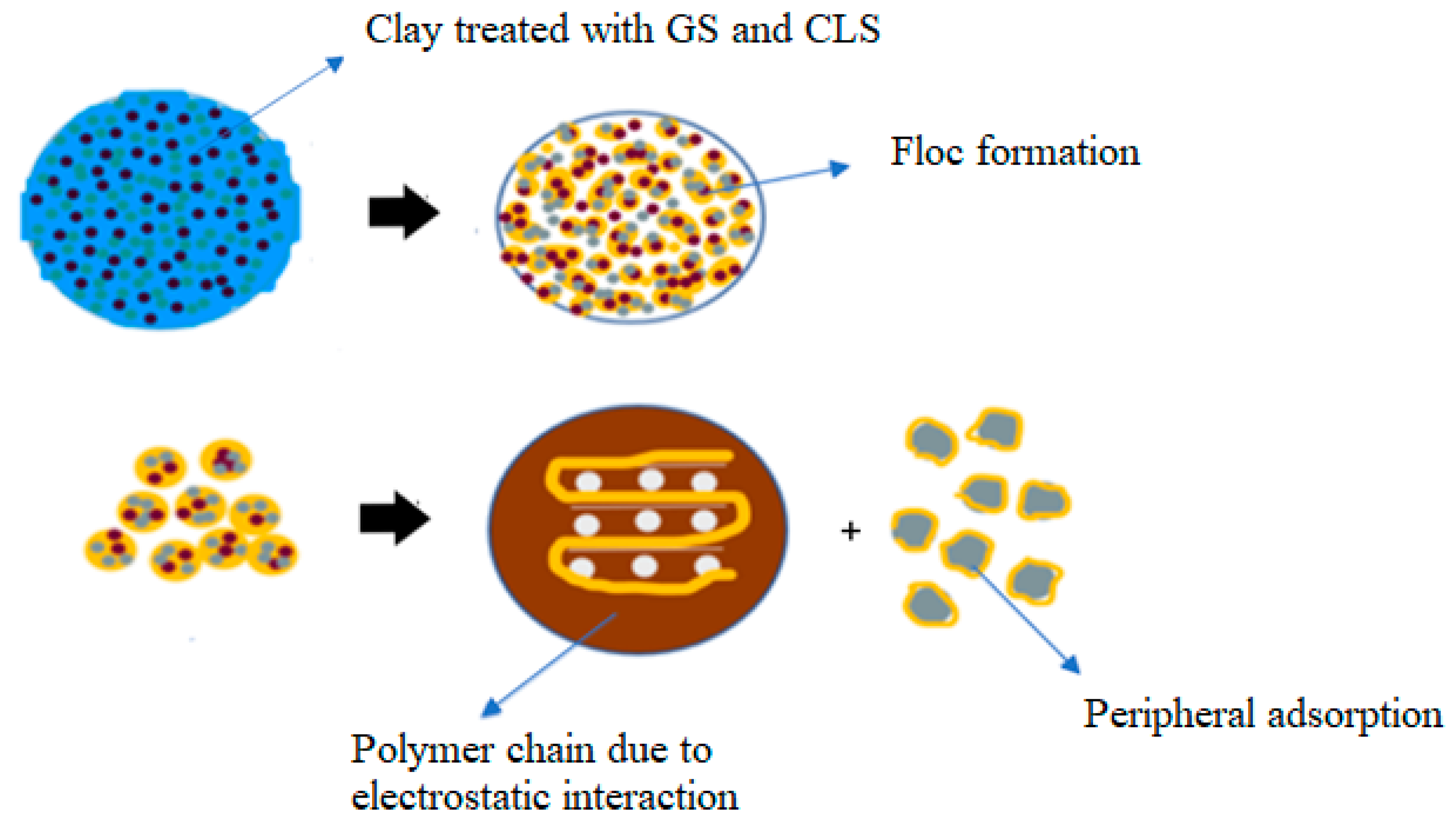

3.2.4. Effect of Porosity

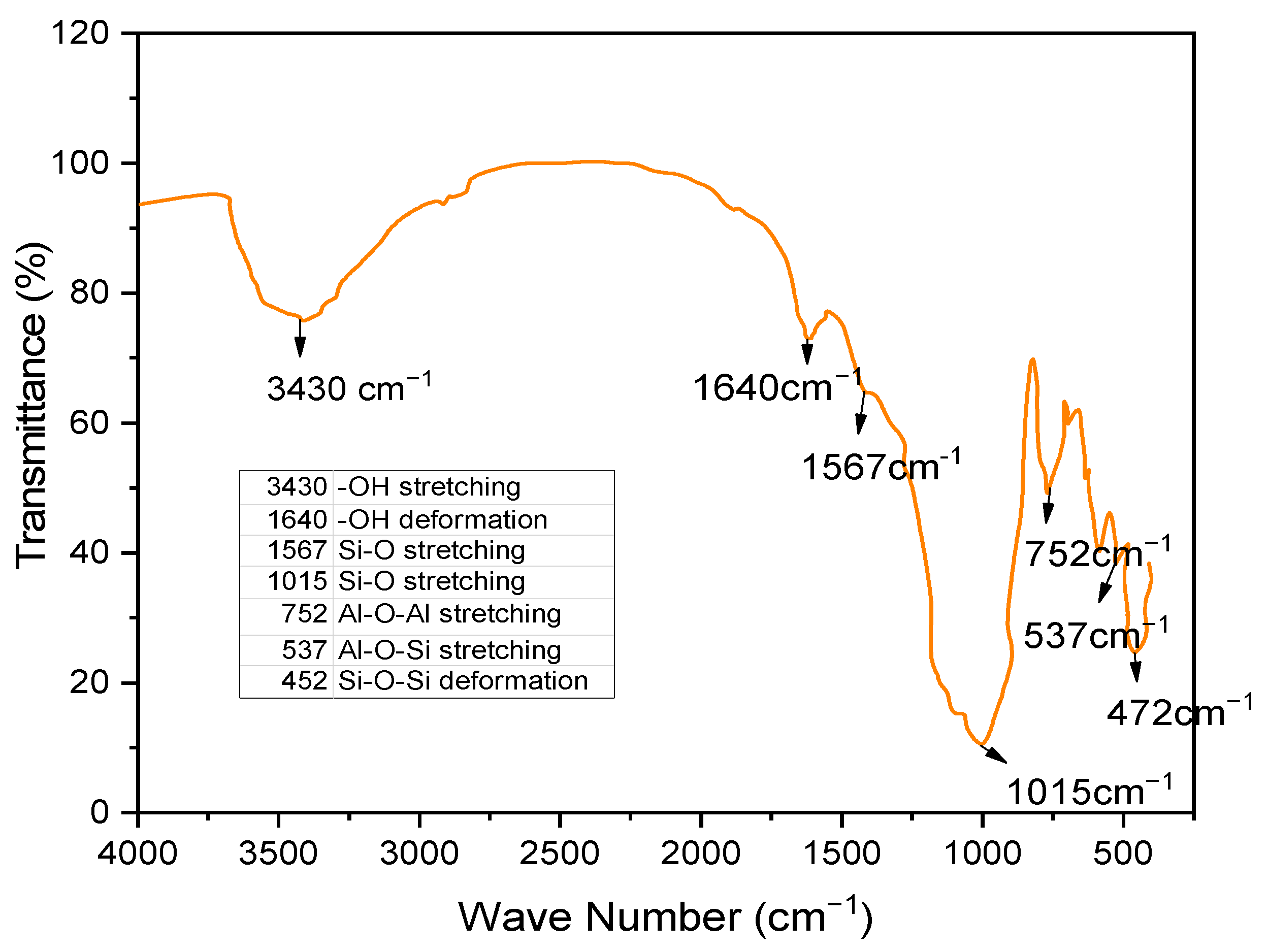

3.2.5. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopic (FTIR) Behavior

3.3. Discussion of Reliability Analysis

3.3.1. Effect of CP on βCBR of GS- and CLS-Treated Soil

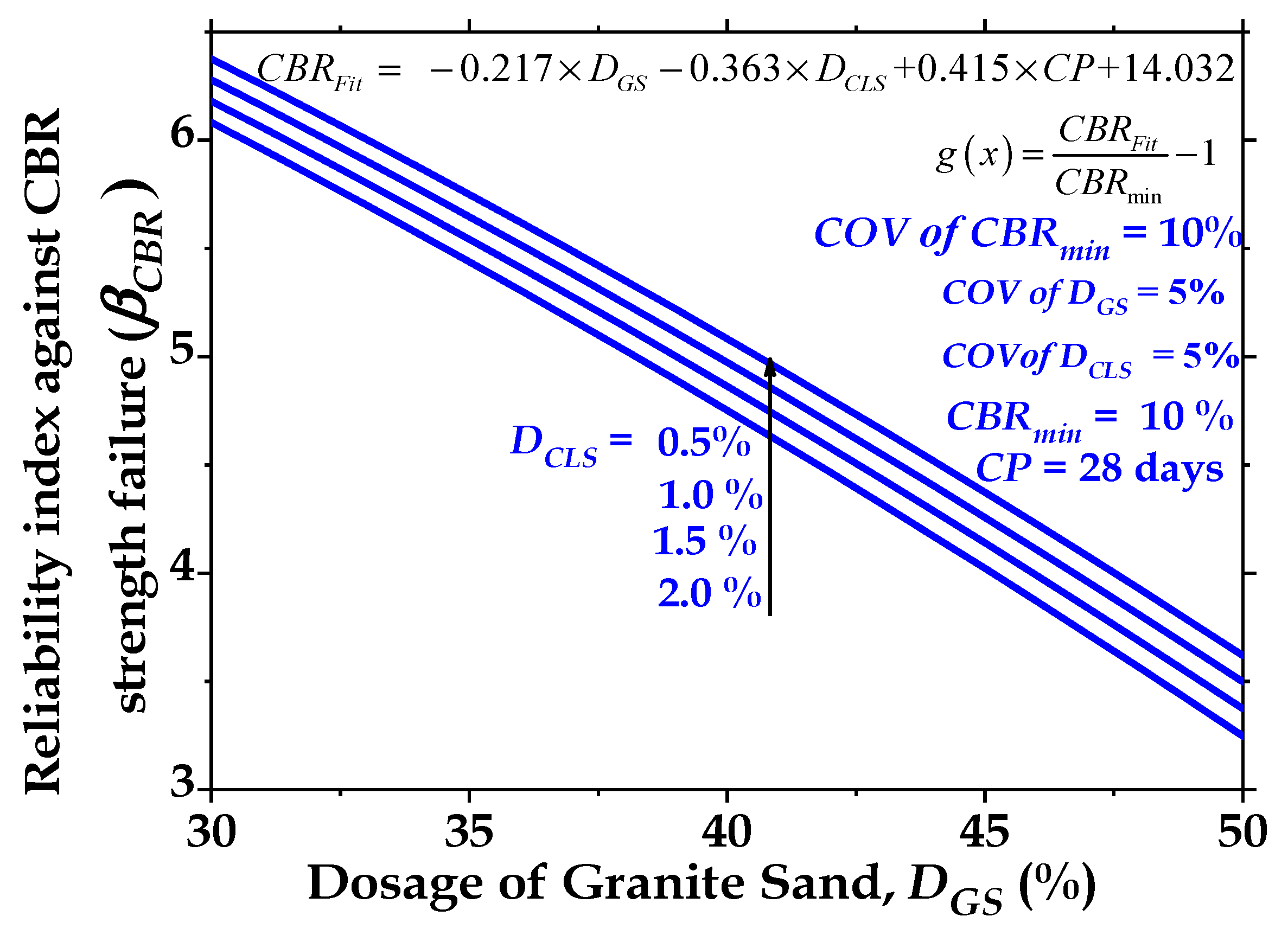

3.3.2. Effect of Dosage of Granite Sand (DGS) on Reliability Index (βCBR)

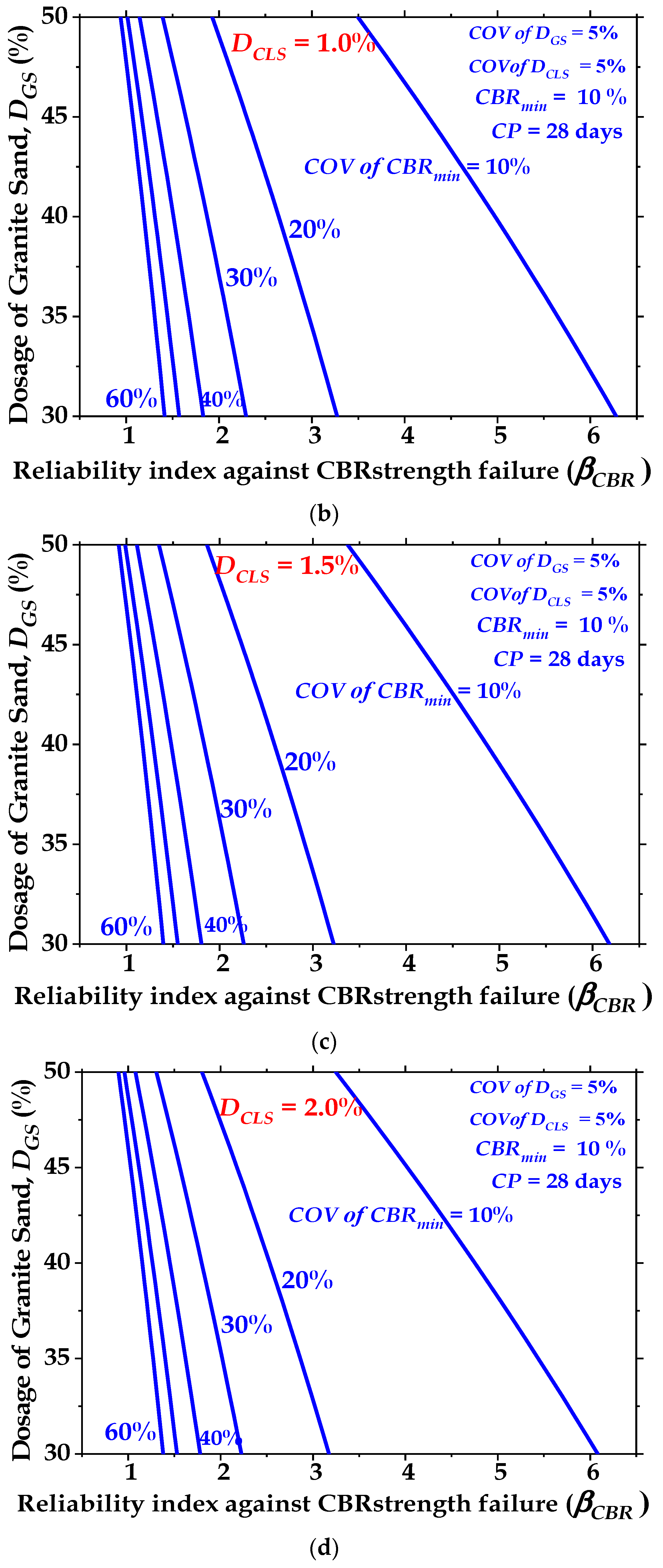

3.3.3. Effect of Dosage of Calcium Lignosulfonate (DCLS) on Reliability Index (βCBR)

3.3.4. Optimal Dosages of Granite Sand (DGS) and Calcium Lignosulfonate (DCLS) for 28-Day Curing Period

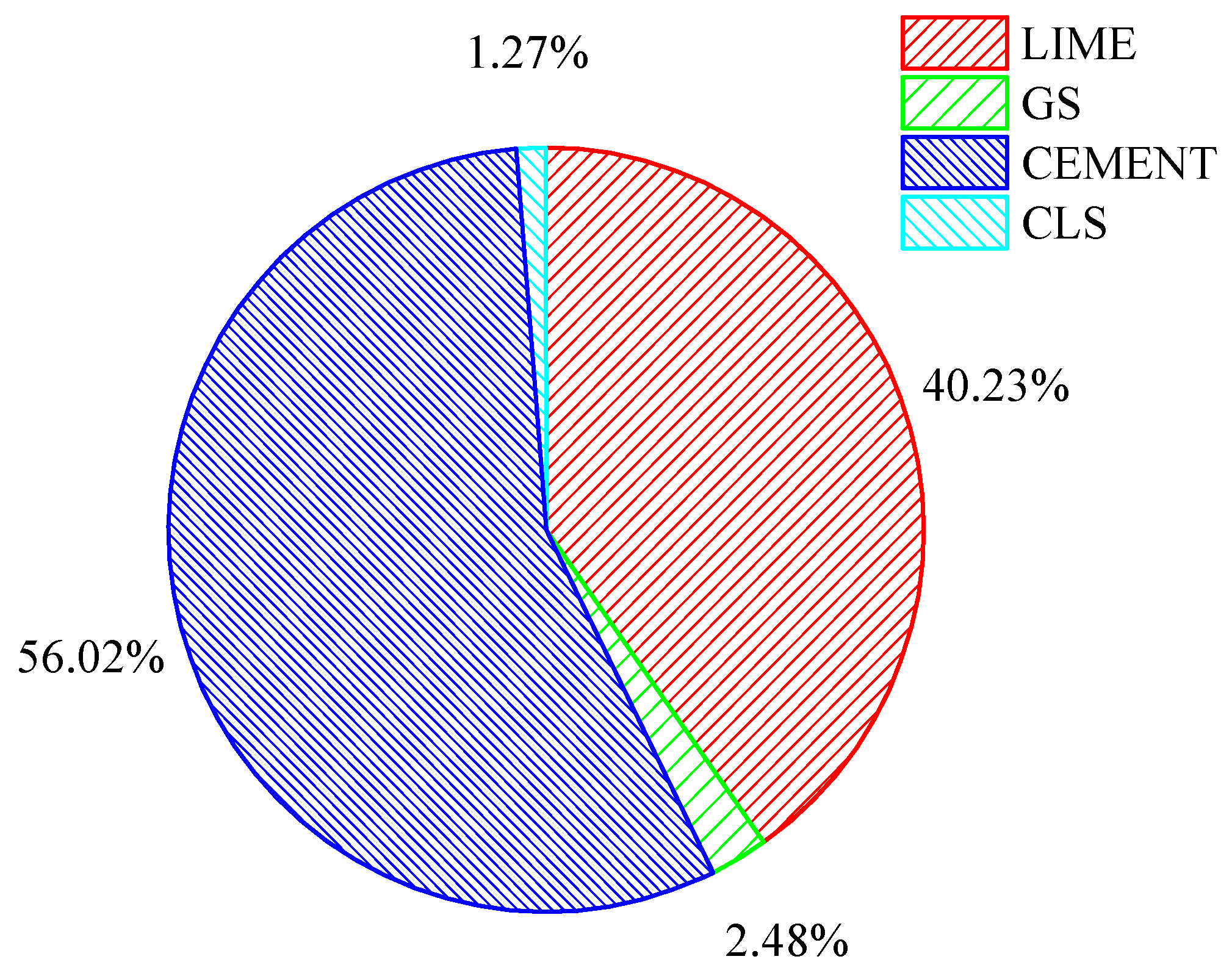

3.4. Discussion of Carbon Footprint Analysis

3.4.1. Detailed Description of the Stages Involved in the Estimation of CO2 Emissions for the Assumed Typical Pavement Subgrade

3.4.2. Comparison of Carbon Emissions of Different Stabilizers

4. Summary and Conclusions

- The addition of GS to the virgin soil at a constant volume reduces the CBR of the clay-GS matrix. The addition of CLS to the clay-GS mix enhances the clay-GS adhesion, resulting in higher CBR values of clay-GS-CLS mixes. At 0.5% CLS, the CBR values increased for the M1, M2, and M3 mixes, and the effect was more pronounced with an increase in the curing period. However, with a further increase in the CLS dosage up to 1.5%, the penetration resistance and CBR values were reduced, except at the 2% dosage.

- Strong and prominent chains are observed for 0.5% CLS in the presence of any dosage of GS due to the formation of chemical bonds. These are evidenced by micrograph images (SEM) and infrared spectra (FTIR).

- The reliability-based design optimization has revealed that the mean values of DGS and DCLS are the most sensitive random parameters that significantly influence the subgrade material stability of low-volume roads.

- The COV of the minimum specified value of the CBR considerably influences the stability of low-volume roads constructed with the clay soil blended with GS and CLS.

- It is demonstrated that the volumes of granite sand (DGS) and calcium lignosulfonate (DCLS) should be decreased for the desired performance of low-volume roads with an increase in the COV of CBRmin from 10 to 60%.

- The addition of 30 to 50% DGS and 0.5% to 2.0% DCLS is inadequate to obtain the desired performance of low-volume roads at βCBR ≤ 3.0 in terms of the CBR strength when the COV of CBRmin is 30%.

- The embodied carbon emission factors of GS and CLS are 0.00526 and 0.2, respectively. These values are relatively low compared to conventional stabilizers such as lime (0.76) and cement (0.95).

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Abbreviation | Full form |

| GS | Granite sand |

| CLS | Calcium lignosulfonate |

| CP (days) | Curing period |

| M1 | 70% clay and 30% GS |

| M2 | 60% clay and 40% GS |

| M3 | 50% clay and 50% GS |

| M1CLS0.5 | 70% clay and 30% GS and 0.5% CLS |

| M1CLS1 | 70% clay and 30% GS and 1% CLS |

| M1CLS1.5 | 70% clay and 30% GS and 1.5% CLS |

| M1CLS2 | 70% clay and 30% GS and 2% CLS |

| M2CLS0.5 | 60% clay and 40% GS and 0.5% CLS |

| M2CLS1 | 60% clay and 40% GS and 1% CLS |

| M2CLS1.5 | 60% clay and 40% GS and 1.5% CLS |

| M2CLS2 | 60% clay and 40% GS and 2% CLS |

| M3CLS0.5 | 50% clay and 50% GS and 0.5% CLS |

| M3CLS1 | 50% clay and 50% GS and 1% CLS |

| M3CLS1.5 | 50% clay and 50% GS and 1.5% CLS |

| M3CLS2 | 50% clay and 50% GS and 2% CLS |

| DGS | Dosage of GS |

| DCLS | Dosage of CLS |

| CBR (%) | California Bearing Ratio of soil |

| (%) | California Bearing Ratio of soil obtained from curve fitting |

| R2 | Coefficient of multiple determination |

References

- Ta’Negonbadi, B.; Noorzad, R.; Ta’Negonbadi, M. Cyclic undrained properties of stabilised expansive clay with lignosulfonate. Géoméch. Geoengin. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivapullaiah, P.V.; Moghal, A.A.B. Role of Gypsum in the Strength Development of Fly Ashes with Lime. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2011, 23, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghal, A.A.B.; Vydehi, V.; Moghal, M.B.; Almatrudi, R.; AlMajed, A.; Al-Shamrani, M.A. Effect of Calcium-Based Derivatives on Consolidation, Strength, and Lime-Leachability Behavior of Expansive Soil. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2020, 32, 04020048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghal, A.A.B.; Obaid, A.A.K.; Al-Refeai, T.O.; Al-Shamrani, M.A. Compressibility and Durability Characteristics of Lime Treated Expansive Semiarid Soils. J. Test. Eval. 2015, 43, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, R.; Al-Harthy, A.; Al-Shamsi, K.; Al-Zubeidi, M. Cement Stabilization of Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement Aggregate for Road Bases and Subbases. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2002, 14, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Swaidani, A.; Hammoud, I.; Meziab, A. Effect of adding natural pozzolana on geotechnical properties of lime-stabilized clayey soil. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2016, 8, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-Rawas, A.A.; Taha, R.; Nelson, J.D.; Al-Shab, B.; Al-Siyabi, H. A Comparative Evaluation of Various Additives Used in the Stabilization of Expansive Soils. Geotech. Test. J. 2002, 25, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, D. Lime-Induced Heave in Sulfate-Bearing Clay Soils. J. Geotech. Eng. 1988, 114, 150–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, G.V.L.N.; Kavya, K.S.; Krishna, A.V.; Ganesh, B. Chemical stabilization of sub-grade soil with gypsum and NaCl. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Technol. 2016, 9, 569. [Google Scholar]

- Kolay, P.K.; Pui, M.P. Peat Stabilization using Gypsum and Fly Ash. J. Civ. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2010, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, T.; Cai, G.; Liu, S. Application of Lignin-Stabilized Silty Soil in Highway Subgrade: A Macroscale Laboratory Study. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2018, 30, 04018034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vydehi, K.V.; Moghal, A.A.B.; Basha, B.M. Reliability-Based Design Optimization of Biopolymer-Amended Soil as an Alternative Landfill Liner Material. J. Hazard. Toxic Radioact. Waste 2022, 26, 04022011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Shahin, M.A.; Cord-Ruwisch, R. Bio-cementation of sandy soil using microbially induced carbonate precipitation for marine environments. Géotechnique 2014, 64, 1010–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moghal, A.A.B.; Chittoori, B.C.; Basha, B.M.; Al-Shamrani, M.A. Target Reliability Approach to Study the Effect of Fiber Reinforcement on UCS Behavior of Lime Treated Semiarid Soil. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2017, 29, 04017014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhan, W.; Zheng, K.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C.; Chen, R. Stabilization of heavy metal-contaminated soils by biochar: Challenges and recommendations. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 729, 139060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, M.; Heeralal, M.; Moghal, A.A.B. Characterization studies on coal gangue for sustainable geotechnics. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2020, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfaq, M.; Moghal, A.A.; Basha, B.M. Reliability-Based Design Optimization of Chemically Stabilized Coal Gangue. J. Test. Eval. 2021, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, M.K.; Das, S.K. Effect of substitution of sand stone dust for quartz and clay in triaxial porcelain composition. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2012, 35, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.K.; Jha, A.K. Improvement in Subgrade Soils with Marble Dust for Highway Construction: A Comparative Study. Indian Geotech. J. 2020, 50, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amulya, G.; Moghal, A.A.B.; Almajed, A. A State-of-the-Art Review on Suitability of Granite Dust as a Sustainable Additive for Geotechnical Applications. Crystals 2021, 11, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, R.; Udoeyo, F.F.; Takkalapelli, K.V. Geotechnical Properties of Problem Soils Stabilized with Fly Ash and Limestone Dust in Philadelphia. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2011, 23, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadir, A.A.; Hassan, M.I.H.; Sarani, N.A.; Rahim, A.S.A.; Ismail, N. Physical and mechanical properties of quarry dust waste incorporated into fired clay brick. AIP Conf. Proc. 2017, 1835, 020040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zafar, M.S.; Javed, U.; Khushnood, R.A.; Nawaz, A.; Zafar, T. Sustainable incorporation of waste granite dust as partial replacement of sand in autoclave aerated concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 250, 118878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, C.B.; Lim, J.S.; Ramli, M.B. The mechanical strength and durability properties of ternary blended cementitious composites containing granite quarry dust (GQD) as natural sand replacement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 197, 291–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivrikaya, O.; Kıyıldı, K.R.; Karaca, Z. Recycling waste from natural stone processing plants to stabilise clayey soil. Environ. Earth Sci. 2014, 71, 4397–4407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Igwe, O.; Adepehin, E.J. Alternative Approach to Clay Stabilization Using Granite and Dolerite Dusts. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2017, 35, 1657–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhakar, S.; Duraisekaran, E.; Vignesh, G.D.; Kanna, G.D. Performance Evaluation of Quarry Dust Treated Expansive Clay for Road Foundations. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civ. Eng. 2021, 45, 2637–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonkwo, U.N.; Arinze, E.E.; Ubochi, S.U. Predictive Model for Elapsed Time Between Mixing Operation and Compaction of Lateritic Soil Treated with Lime and Quarry Dust for Sub-base of Low-cost Roads. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2021, 15, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indiramma, P.; Sudharani, C.H. Scanning electron microscope analysis of fly ash, quarry dust stabilized soil. In Soil Testing, Soil Stability and Ground Improvement: Proceedings of the 1st GeoMEast International Congress and Exhibition, Egypt 2018 on Sustainable Civil Infrastructures 1; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 284–296. [Google Scholar]

- Mudgal, A.; Sarkar, R.; Sahu, A.K. Effect of lime and stone dust in the geotechnical properties of black cotton soil. GEOMATE 2014, 7, 1033–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetia, M.; Sridharan, A. A Review on the Influence of Rock Quarry Dust on Geotechnical Properties of Soil. Geo-Chicago 2016, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyankara, N.H.; Wijesooriya, R.M.S.D.; Jayasinghe, S.N.; Wickramasinghe, W.R.M.B.E.; Yapa, S.T.A.J. Suitability of Quarry Dust in Geotechnical Applications to Improve Engineering Properties. Eng. J. Inst. Eng. Sri Lanka 2009, 42, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Indraratna, B.; Athukorala, R.; Vinod, J. Estimating the Rate of Erosion of a Silty Sand Treated with Lignosulfonate. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2013, 139, 701–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chandna, S.; Bhardwaj, S.K.; Paul, S.; Bhaumik, J. Synthesis and Applications of Lignin-Derived Hydrogels. Lignin Biosynth. Transform. Ind. Appl. 2020, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.-Y.; Prayogo, D.; Wu, Y.-W. Prediction of permanent deformation in asphalt pavements using a novel symbiotic organisms search–least squares support vector regression. Neural Comput. Appl. 2018, 31, 6261–6273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, S.; Cai, G.; Puppala, A.J. Experimental investigation of thermal and mechanical properties of lignin treated silt. Eng. Geol. 2015, 196, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Cai, G.; Liu, S.; Puppala, A.J. Engineering properties and microstructural characteristics of foundation silt stabilized by lignin-based industrial by-product. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2016, 20, 2725–2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indraratna, B.; Muttuvel, T.; Khabbaz, H.; Armstrong, R. Predicting the Erosion Rate of Chemically Treated Soil Using a Process Simulation Apparatus for Internal Crack Erosion. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2008, 134, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohpeyma, H.R.; Vakili, A.H.; Moayedi, H.; Panjsetooni, A.; Nazir, R. Investigating the Effect of Lignosulfonate on Erosion Rate of the Embankments Constructed with Clayey Sand. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabitha, B.S.; Evangeline, Y.S. Stabilisation of Kuttanad Soil Using Calcium and Sodium Lignin Compounds. In Proceedings of the Indian Geotechnical Conference 2019: IGC-2019, Nantes, France, 27–31 August 2019; Springer: Singapore, 2021; Volume III, pp. 249–258. [Google Scholar]

- Ashfaq, M.; Lal, M.H.; Moghal, A.A.B.; Murthy, V.R. Carbon Footprint Analysis of Coal Gangue in Geotechnical Engineering Applications. Indian Geotech. J. 2019, 50, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vukotic, L.; Fenner, R.A.; Symons, K. Assessing embodied energy of building structural elements. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Eng. Sustain. 2010, 163, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, C.; Soga, K.; Nicolson, D.; O’Riordan, N. Embodied Energy and Gas Emissions of Retaining Wall Structures. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Geotech. Eng. 2011, 137, 958–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shillaber, C.M.; Mitchell, J.K.; Dove, J.E. Energy and Carbon Assessment of Ground Improvement Works. II: Working Model and Example. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2016, 142, 04015084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmsel, M. Contribution of Sand Filled Geotextile Tubes to Decrease Carbon Footprint Emissions in Building Marine Structures. In Coastal Management: Changing Coast, Changing Climate, Changing Minds; ICE Publishing: London, UK, 2016; pp. 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bouazza, A.; Heerten, G. Geosynthetic applications—Sustainability aspects. In Handbook of Geosynthetic Engineering; ICE Publishing: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM Committee D-18 on Soil and Rock. Standard Practice for Classification of Soils for Engineering Purposes (Unified Soil Classification System) 1; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.astm.org/d2487-17.html (accessed on 27 February 2023).

- Alazigha, D.P.; Indraratna, B.; Vinod, J.S.; Ezeajugh, L.E. The swelling behaviour of lignosulfonate-treated expansive soil. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Ground Improv. 2016, 169, 182–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chavali, R.V.P.; Reshmarani, B. Characterization of expansive soils treated with lignosulfonate. Int. J. Geo-Eng. 2020, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM. D698 Standard Test Methods for Laboratory Compaction Characteristics of Soil Using Standard Effort (12,400 ft-lbf/ft3 (600 kN-m/m3)); ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2012; Available online: https://www.astm.org/d0698-12r21.html (accessed on 27 February 2023).

- ASTM. D1883 Standard Test Method for California Bearing Ratio (CBR) of Laboratory-Compacted Soils; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.astm.org/d1883-21.html (accessed on 27 February 2023).

- Alazigha, D.P.; Vinod, J.S.; Indraratna, B.; Heitor, A. Potential use of lignosulfonate for expansive soil stabilisation. Environ. Geotech. 2018, 6, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- González, A.; Chamorro, A.; Barrios, I.; Osorio, A. Characterization of unbound and stabilized granular materials using field strains in low volume roads. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 176, 333–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafoori, N.; Nyknahad, D.; Wang, L. Use of pulverised and fluidised combustion coal ash in secondary road construction. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2013, 14, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amulya, G.; Moghal, A.A.B.; Basha, B.M.; Almajed, A. Coupled Effect of Granite Sand and Calcium Lignosulphonate on the Strength Behavior of Cohesive Soil. Buildings 2022, 12, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IR Congress. Guidelines for Soil and Granular Material Stabilization Using Cement, Lime and Fly Ash—IRC SP 89; India Offset Press: New Delhi, India, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- IR Congress. Guidelines for the Design of Flexible Pavements for Low Volume Rural Roads—IRC SP 72; India Offset Press: New Delhi, India, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Basha, B.M.; Babu, G.S. Seismic reliability assessment of external stability of reinforced soil walls using pseudo-dynamic method. Geosynth. Int. 2009, 16, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basha, B.M.; Babu, G.S. Seismic reliability assessment of internal stability of reinforced soil walls using pseudo-dynamic method. Geosynth. Int. 2011, 18, 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basha, B.; Babu, G. Target reliability-based optimisation for internal seismic stability of reinforced soil structures. Géotechnique 2012, 62, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basha, B.M.; Babu, G.S. Optimum Design for External Seismic Stability of Geosynthetic Reinforced Soil Walls: Reliability Based Approach. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2010, 136, 797–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divinsky, M.; Ishai, I.; Livneh, M. Probabilistic Approach to Pavement Design Based on Generalized California Bearing Ratio Equation. J. Transp. Eng. 1998, 124, 582–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.B.; Buch, N. Reliability-based pavement design model accounting for inherent variability of design parameters. In Proceedings of the 82nd Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 12–16 January 2003; pp. 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Retherford, J.Q.; McDonald, M. Reliability Methods Applicable to Mechanistic–Empirical Pavement Design Method. Transp. Res. Rec. 2010, 2154, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sani, J.E.; Bello, A.O.; Nwadiogbu, C.P. Reliability estimate of strength characteristics of black cotton soil pavement sub-base stabilized with bagasse ash and cement kiln dust. Civ. Environ. Res. 2014, 6, 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Moghal, A.A.B.; Basha, B.M.; Chittoori, B.; Al-Shamrani, M.A. Effect of Fiber Reinforcement on the Hydraulic Conductivity Behavior of Lime-Treated Expansive Soil—Reliability-Based Optimization Perspective. Geo-China 2016, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghal, A.A.B.; Chittoori, B.C.; Basha, B.M. Effect of fibre reinforcement on CBR behaviour of lime-blended expansive soils: Reliability approach. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2018, 19, 690–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, V.R.; White, D.J.; Ceylan, H.; Stevens, L.J. Design Guide for Improved Quality of Roadway Subgrades and Subbases. Iowa Highway Research Board (IHRB Project TR-525). 2008. Available online: https://publications.iowa.gov/19978/ (accessed on 7 September 2008).

- Ashfaq, M.; Moghal, A.A.B.; Basha, B.M.; Moghal, A.A.B. Carbon Footprint Analysis on the Expansive Soil Stabilization Techniques; IFCEE: Dallas, TX, USA, 2021; pp. 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.; Coello, J.; Kemp, S.; Williams, I. Carbon footprinting for climate change management in cities. Carbon Manag. 2011, 2, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shillaber, C.M.; Mitchell, J.K.; Dove, J.E. Energy and Carbon Assessment of Ground Improvement Works. I: Definitions and Background. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2016, 142, 04015083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, L.; Phear, A.; Nicholson, D.; Pantelidou, H.; Soga, K.; Guthrie, P.; Kidd, A.; Fraser, N. Carbon dioxide from earthworks: A bottom-up approach. In Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers-Civil Engineering; Thomas Telford Ltd.: London, UK, 2011; Volume 164, pp. 66–72. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, G.; Jones, C.; Lowrie, E.F.; Tse, P. Embodied carbon. In The Inventory of Carbon and Energy; ICE Publishing: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, S.H.A.; Arif, M.; Sabir, M.A.; Rehman, Q. Impact of Igneous Rock Admixtures on Geotechnical Properties of Lime Stabilized Clay. Civ. Environ. Eng. 2020, 16, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekha, B.M.; Sarang, G.; Shankar, A.R. Effect of Electrolyte Lignin and Fly Ash in Stabilizing Black Cotton Soil. Transp. Infrastruct. Geotechnol. 2015, 2, 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinod, J.S.; Indraratna, B.; Mahamud, M.A. Stabilisation of an erodible soil using a chemical admixture. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Ground Improv. 2010, 163, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ta’Negonbadi, B.; Noorzad, R. Stabilization of clayey soil using lignosulfonate. Transp. Geotech. 2017, 12, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Sahoo, J.P. Undrained cyclic loading response of lignosulfonate treated high plastic clay. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2021, 150, 106943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharmila, B.; Bhuvaneshwari, S.; Landlin, G. Application of lignosulphonate—A sustainable approach towards strength improvement and swell management of expansive soils. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2021, 80, 6395–6413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; She, W.; Wei, L.; Zuo, W.; Hu, X.; Hong, J.; Miao, C. Stabilization Mechanism of Calcium Lignosulphonate Used in Expansion Sensitive Soil. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Sci. Ed. 2020, 35, 847–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passaretti, M.G.; Ninago, M.D.; Paulo, C.I.; Petit, A.; Irassar, E.F.; Vega, D.A.; Villar, M.A.; Lopez, O.V. Biocomposites Based on Thermoplastic Starch and Granite Sand Quarry Waste. J. Renew. Mater. 2019, 7, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Friedrich, F.; Heissler, S.; Faubel, W.; Nuesch, R.; Weidler, P.G. Cu(II)-intercalated muscovite: An infrared spectroscopic study. Vib. Spectrosc. 2007, 43, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, G.; Jones, C. Inventory of Carbon & Energy (ICE); Sustainable Energy Research Team, Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Bath: Bath, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, S.C.; Diegel, S.W.; Boundy, R.G. Transportation Energy Data Book: Edition 31. Rep. No. ORNL-6987; U.S. Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- Kecojevic, V.; Komljenovic, D. Impact of Bulldozer’s Engine Load Factor on Fuel Consumption, CO2 Emission and Cost. Am. J. Environ. Sci. 2011, 7, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garzón, E.; Cano, M.; O’kelly, B.C.; Sánchez-Soto, P.J. Effect of lime on stabilization of phyllite clays. Appl. Clay Sci. 2016, 123, 329–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prusinski, J.R.; Bhattacharja, S. Effectiveness of Portland Cement and Lime in Stabilizing Clay Soils. Transp. Res. Rec. 1999, 1652, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Property | Value (Clay) | Value (GS) | Chemical Composition | Value of Clay (%) | Value of GS (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific gravity | 2.62 | 2.72 | Silica (SiO2) | 55.34 | 53.06 |

| Liquid limit (%) | 45.13 | - | Alumina (Al2O3) | 9.92 | 6.16 |

| Plastic limit (%) | 22.34 | - | Calcium Oxide (CaO) | 1.06 | 1.64 |

| Plasticity Index (%) | 22.79 | - | Magnesium Oxide (MgO) | 1.97 | 5.86 |

| Shrinkage limit (%) | 13 | - | Titanium Oxide (TiO2) | 1.13 | 0.32 |

| % Fines | 63 | 10 | Ferric Oxide (Fe2O3) | 8.15 | 9.06 |

| IS classification | CI | SP-SM | Sodium Oxide (Na2O) | 0.31 | 1.37 |

| DFS (%) | 33 | - | |||

| Maximum Dry Density (g/cc) | 1.75 | 2.1 | |||

| Optimum Moisture Content (%) | 16.3 | 8.3 | |||

| CP (Days) | CBR | Residual | % Error | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2.78 | 2.79 | −0.01 | −0.25 |

| 7 | 2.94 | 2.93 | 0.01 | 0.37 |

| 28 | 3.26 | 3.26 | 0 | −0.12 |

(Days) | (%) | (%) | CBR | Residual | % Error | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | 30 | 0.5 | 9.50 | 10.26 | −0.76 | −7.96 |

| 1.0 | 10.00 | 10.07 | −0.07 | −0.74 | ||

| 1.5 | 11.30 | 9.89 | 1.41 | 12.45 | ||

| 2.0 | 9.00 | 9.71 | −0.71 | −7.90 | ||

| 40 | 0.5 | 7.80 | 8.09 | −0.29 | −3.70 | |

| 1.0 | 8.00 | 7.91 | 0.09 | 1.16 | ||

| 1.5 | 8.20 | 7.73 | 0.47 | 5.78 | ||

| 2.0 | 7.50 | 7.54 | −0.04 | −0.59 | ||

| 50 | 0.5 | 6.80 | 5.92 | 0.88 | 12.91 | |

| 1.0 | 6.40 | 5.74 | 0.66 | 10.30 | ||

| 1.5 | 4.00 | 5.56 | −1.56 | −38.98 | ||

| 2.0 | 5.30 | 5.38 | −0.08 | −1.46 | ||

| 28 | 30 | 0.5 | 20.60 | 18.97 | 1.63 | 7.89 |

| 1.0 | 15.00 | 18.79 | −3.79 | −25.29 | ||

| 1.5 | 15.00 | 18.61 | −3.61 | −24.08 | ||

| 2.0 | 18.00 | 18.43 | −0.43 | −2.39 | ||

| 40 | 0.5 | 17.30 | 16.81 | 0.49 | 2.84 | |

| 1.0 | 19.60 | 16.63 | 2.97 | 15.17 | ||

| 1.5 | 20.50 | 16.45 | 4.05 | 19.78 | ||

| 2.0 | 21.20 | 16.26 | 4.94 | 23.28 | ||

| 50 | 0.5 | 13.33 | 14.64 | −1.31 | −9.84 | |

| 1.0 | 15.40 | 14.46 | 0.94 | 6.11 | ||

| 1.5 | 10.00 | 14.28 | −4.28 | −42.78 | ||

| 2.0 | 12.50 | 14.10 | −1.60 | −12.77 |

| Stage I | Material (1) | Amount (m3) (2) | Unit Weight (kg/m3) (3) | Weight (t) (4) | ECF (5) | Embodied Carbon (t) CO2e/t (6) = (4) × (5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Embodied carbon of the material | Clay (CI) | 2250 | 1750 | 2.75 × 103 | 0.0056 | 15.4 |

| GS | 2250 | 1750 | 1.179 × 103 | 0.0052 | 6.13 | |

| CLS | 2250 | - | 19.65 | 0.2 | 3.93 | |

| Water | 6405.9 | 1000 | 0.6405 × 103 | 0.001 | 0.64 | |

| Total CO2(t) emissions in Stage I = 26.1 | ||||||

| Stage II | Process | Vehicle | Capacity (t/L) | No. of Loadings | Total Fuel (L) | ECF (Fuel Based Equipment) | Embodied Carbon (t) CO2e/t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excavation and Procurement | Clay procurement | Pickup excavator | 10 | 275 | 275 | 3.25 | 893.75 | |

| GS procurement | Pickup excavator | 10 | 118 | 118 | 3.25 | 383.5 | ||

| CLS | Pickup excavator | 10 | 2 | 2 | 3.25 | 6.5 | ||

| Total CO2 | 1283.75 | |||||||

| Haulage | Process | Vehicle | Capacity (t/L) | Distance (km) | Trips | Total fuel (L) | Embodied carbon CO2e/t (t) | |

| Haulage | Clay | Heavy-duty dumper | 25 | 1 | 55 | 55 | 3.25 | 178.75 |

| Granite sand | Heavy-duty dumper | 25 | 1 | 24 | 23.58 | 3.25 | 76.635 | |

| Calcium lignosulfonate | Heavy-duty dumper | 25 | 1 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 3.25 | 1.277 | |

| Total CO2 | 256.66 | |||||||

| Total CO2(t) emissions in Stage II = 1540.4 | ||||||||

| Stage III | Process | Vehicle/Machine | Capacity | No. of Trips | Total Fuel (L) | ECF | Embodied Carbon (t) CO2e/t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site operation | Spreading | Bulldozer | 10 t/L | 393 | 393 | 3.25 | 1276.9 |

| Haulage | Mixing of CLS | Slurry mixer | 0.5 t (50 lb) | 40 | 40 | 3.25 | 127.7 |

| Spraying of CLS | Distributor truck | 500 L | 1.3 | 1.3 | 3.25 | 4.25 | |

| Compaction | Smooth Wheel Roller | 12 t/L | 328 | 328 | 3.25 | 1064.4 | |

| Total CO2 | 3622.7 | ||||||

| Total CO2(t) emissions in Stage III = 3622.7 | |||||||

| Stage | Operation | Embodied Carbon (CO2e/t) |

|---|---|---|

| Stage I | Material | 26.1 |

| Stage II | Haulage | 1283.75 |

| Procurement | 256.66 | |

| Stage III | Site operations | 3622.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Amulya, G.; Moghal, A.A.B.; Almajed, A. Sustainable Binary Blending for Low-Volume Roads—Reliability-Based Design Approach and Carbon Footprint Analysis. Materials 2023, 16, 2065. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16052065

Amulya G, Moghal AAB, Almajed A. Sustainable Binary Blending for Low-Volume Roads—Reliability-Based Design Approach and Carbon Footprint Analysis. Materials. 2023; 16(5):2065. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16052065

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmulya, Gudla, Arif Ali Baig Moghal, and Abdullah Almajed. 2023. "Sustainable Binary Blending for Low-Volume Roads—Reliability-Based Design Approach and Carbon Footprint Analysis" Materials 16, no. 5: 2065. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16052065

APA StyleAmulya, G., Moghal, A. A. B., & Almajed, A. (2023). Sustainable Binary Blending for Low-Volume Roads—Reliability-Based Design Approach and Carbon Footprint Analysis. Materials, 16(5), 2065. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16052065